A Rare Case Report

Do exercise programs developed using the results of exercise tests results really work in chronic fatigue syndrome? The folks at the Workwell Foundation use exercise tests to determine the heart rate at which your body begins to rely heavily on anaerobic energy production – and spew out toxins known to cause pain and fatigue.

They believe that many people with ME/CFS increase their pain and fatigue levels unknowingly by working at heart rates that keep them primarily using anaerobic energy. Identifying the heart rate at which people with ME/CFS enter the ‘anaerobic zone’ should allow them to slow down and thus have less pain, fatigue and cognitive problems, and feel healthier.

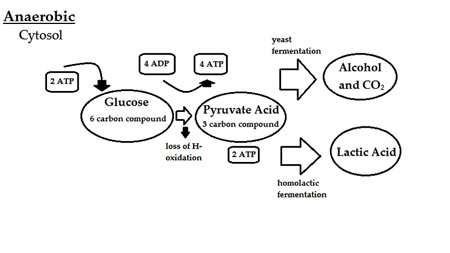

(Note that anaerobic energy production is used at the beginning of the exercise period. After that is exhausted (usually quickly) aerobic energy production is primarily used. After the capacity for aerobic energy production is used up our cells turn to using anaerobic energy. It’s the capacity for aerobic energy production that appears t be blunted in ME/CFS.)

That’s the theory. Studies do show that people with chronic fatigue syndrome who regularly venture outside their ‘energy envelope’ have more pain and fatigue than those who don’t.

In this case Staci Stevens, the director at the Workwell Foundation, reported what happened symptomatically and physiologically, to one ME/CFS patient who followed a heart-rate based activity program tailored specifically for her, for a year.

The Patient….

Patient X was steadily declining before she began Workwell’s exercise program.

was a 28-year-old female diagnosed with ME/CFS and orthostatic intolerance. Fully ensconced in a push-crash pattern, she increased her activities when she felt better, then overdid it and crashed – waited until she felt better—and then did it all over again.

Over time she found she was crashing for longer and longer periods. No longer employed, and finding that even her household chores were becoming too difficult, she was clearly on a slippery slope downwards.

Cardiopulmonary tests indicated her peak volume of oxygen consumption was low normal (which is not uncommon for ME/CFS), and that her cardiorespiratory system failed to respond normally to exercise.

Specifically, her blood pressure, respiration, and ventilation (the amount of oxygen getting into her lungs) were all blunted during exercise. (This is called chronotropic incompetence and it’s often seen in ME/CFS.) Her blood pressure dropped when she stood (orthostatic intolerance) and failed to rise while she was on the stationary bike.

She felt well during and for six hours after the exercise test, and then started to relapse. She estimated it took her a month to recover.

Chronotropic Incompetence (CI)

The inability to reach normal levels of heart rate, stroke volume, and oxygen loading during exercise may be common in ME/CFS and is common in some cardiovascular disorders. During maximal exercise your heart rate should double, your stroke volume (the amount of blood pumped out by the heart at a time) should be 30 percent higher, and you should have fifty percent more oxygen in your arteries as in your veins.

In healthy people CI is associated with increased risk of heart attack and mortality. We’ll have more on chronotropic incompetence in a future blog.

The Plan

Stevens entered the heart rate at which anaerobic energy production became dominant into patient ‘X”s heart monitor. Every time patient ‘X’ exceeded her target heart rate, a beep from her heart rate monitor (HRM) signaled her to sit or lie down.

Lying down was an essential part of her exercise program. No longer did her body have to devote energy to keep blood from pooling in her legs when she stood; when she exercised lying down it could devote all its energy to improving her fitness.

Patient X was provided with flexibility, resistance, and short-term endurance exercises. Diaphragmatic breathing and gentle upper body stretches were included to reduce pain levels. The resistance exercises were done while lying down.

Stevens said the first thing she teaches every patient is to breathe from their diaphragm. Stating that the muscles around the ribs that move the lungs are among the most aerobic in the body, she noted that inhaling and exhaling slowly is an exercise used by people with pulmonary disorders. Yoga, meditation, and other disciplines focus on breathing, as well, to slowly to drop the heart rate, reduce stress, and reduce pain.

Results Suggest Some Healing Can Take Place

Some healing did take place over time.

After a year of heart rate monitor use, deep breathing, flexibility and short-term endurance exercises, how was patient X doing? She reported substantial improvements in general functioning and, importantly, some of her physiological measures notched upwards.

Parts of her body began to respond more normally to exercise. Her respiratory rate (the number of breaths she took), the amount of oxygen she inhaled, and her blood pressure went up dramatically during exercise. At maximum effort during the first test her blood pressure peaked at a mere 112/72. After a year of doing ‘short-term’ endurance exercises below her targeted heart rate, her blood pressure was up to 170/98 and her respiratory rate had increased 42%.

Even though she was still limited aerobically, her heart rate and blood pressure were both increasing normally in response to exercise. It was as if her cardiovascular system had emerged from a state of partial hibernation.

Staci doesn’t have this kind of before/after data from many patients; they get disability, get the exercise program, and they’re gone. But this person came back. Staci was so amazed to see the degree of cardiovascular rehabilitation that had occurred that she asked her what medication she was taking. The answer was “none”… it was all due to the heart rate pacing and exercise program.

This time, instead of the maximal exercise test setting her back a month, it set her back a week.

Anaerobic Threshold Up, Aerobic Capacity Unchanged

Patient X’s VO2 max, i.e., her ability to take and use oxygen to produce energy, stayed about the same, and that’s probably what we’d expect from a program focused on increasing anaerobic (not aerobic) functioning.

Patient X’s anaerobic threshold–the heart rate at which she began producing more of her energy anaerobically–did change, however, and she was able to be active at a significantly higher level (about 20 heartbeats higher) without triggering a negative response.

Staci Steven’s goal was to have Patient X stop triggering the inflammatory response people with ME/CFS experience with exertion. Staci felt that, by staying under her anaerobic threshold, patient X’s body was able to heal over time and respond to stress more normally. As long as she stayed within the aerobic ‘safety zone’ defined by her VO2 max test, she was more active and felt better as well.

This case report provides proof that keeping out of the push-crash cycle not only makes you feel better, it can also physiologically help you to heal.

Workwell provides conditioning consultations and hope to have activity management programs up and running by next year.

- Dig Deeper – Busted! Exercise Study Finds Energy Production System is Broken in Chronic Fatigue Syndrome!

- Dig Deeper – Check out Health Rising’s Exercise Resource Center For Chronic Fatigue Syndromer

- Dig Deeper – Learn more about Workwell and their disability and conditioning consultations and research here.

That’s great news. I have the same problems. question what are causing these heart and respratory issues with cfs? Can this be a cause of the disease or just another by product of this disease? thanks Cort

Jimmy

Thanks Cort for this report. I like how your conclusion reaffirms a basic idea which I find is always at risk of becoming a commonplace taken more or less seriously: avoiding the push-crash cycle. Over time, as with patient X, it can really drag us down ever more. Every new person who comes down with CFS should be made acutely aware of this from day 1, and take it very seriously.

Good for her if she managed to stop the deterioration.

I have a POTS friend that is doing this right now. She was a Physical Therapist and had been doing her best to get better with the idea that exercise would improve things. (Some doctors feel that being de-conditioned can be a cause of POTS. But, as is very obvious with lots of POTS people —exercise and bodily training IS their business and so many were in tip-top condition when POTS showed it’s ugly head.) She has to wear a heart rate monitor around every where and if she goes above her target rate then has to stop whatever she is doing. She feels she is getting stronger and not going down further. Which is what she was doing before with the daily push to exercise. Maybe she will comment as I will be sending this article to her.

Issie

It’s great to read that exercising within ones save limits can actually “physiologically help you to heal.”

While the worst thing we can do is to advice ME/CFS patients to exercise like a normal person outside their safe heart rate threshold, the second worst thing is to say “all exercise is bad for you.”

Thank you for this insightful article, Cort.

Whilst the activity/exercise program that Staci designed would be unique to this patient, I’d still love to know what it consisted of. Dan Moricoli’s video of his earlier yoga work is the only information I am aware of which is likely to be similar. His great improvement seems to be predicated on this careful activity work.

Does anyone have experience of Staci’s program here? It is the combination of varied exercise and careful activities with the alarm set up on the watch that seems particularly useful.

Yes, Dan’s improvement is just incredible; he’s not sport-fishing anymore but to go from being in bed, thrashed about by myoclonic jerks to be being able to get around and work – is nothing short of amazing. Dan was very careful and patient and over time his program really did work…

At some point I’m sure we’ll get more details on Staci’s program….I believe it’s quite similar; a short term endurance exercise followed by rest allowing the heart to return to normal, followed by another little bout etc.

I’m always glad to hear about a patient improving.

It would be interesting to know how Workwell’s/Staci Stevens’ methods apply to people who are sicker than the woman in the case report. It sounds as if she already a pretty good level of function, if she could still do household chores: “No longer employed, and finding that even her household chores were becoming too difficult, she was clearly on a slippery slope downwards.”

Those of us who have to lie without moving all or most of the day can’t do any chores at all; we can’t even bathe without help. How are we supposed to do endurance exercises below the target heart rate when we can’t lift a book off a shelf? As always, it’s important to keep in mind the full spectrum of severity.

Sounds like a plan. Anybody have any heart rate monitor recommendations?

Very good news and I have the same question like Jen.

When I first read about this type of heart rate monitoring, I intuitively felt it worth a try.

I first used a simple pulse-ox clip on – not a good solution, too bulky.

Then I bought a watch that monitors heart rate without the need to use a chest strap. This did not give me the close monitoring that I was looking for.

Next step was Polar heart rate monitors. When I called Polar they said they do not sell any monitors that could run all day. Their units are not designed for all day use. They said the battery would not last very long, plus you have to mail it back to them for a battery replacement.

Finally, I bought a Timex Ironman Road Trainer Heart Rate Monitor on Amazon. It works great although the chest strap is a bit of a bother. It was fairly easy to program in my alarm criteria. The alarm is fairly quiet which I like.

I have been doing this for 3-4 weeks and know I will need to be patient. I have really learned a lot about pacing myself and can easily see how I created push/crash cycles.

Joyce,

I used a Timex heart rate monitor, found it practical and useful, until the wrist display battery went out, at about two months.

The battery on the chest strap was easy to replace, very easy. The battery in the wrist display needed a jeweller to do that, which is to say, too much work for me, I hardly get out of the house. Does it mean I must buy a whole new device every two months?

So I will be curious to know if your Ironman Road Trainer gives you the same problem.

I think this approach has huge potential for success, success being defined as stopping decline, regaining some ordinary function.

I have only had the ironman for about a month. I was pleased that I can replace the chest batteries myself. Hadn’t really thought about the watch itself. I know that those batteries can be replaced at Walmart if you can get the watch to WM. I think the reason to take it to a store is to have it maintain the waterproofing.

My next problem is to resolve the irritation on my chest from the band.

Thank you Joyce for telling your expeience, very helpful! And now my next questions……which may sound stupid but anyway…..

1. Can you explain or anybody else what the difference is between the heart rate monitors – the one like a Watch and the one like chest strap?

2. How did you find out where your alarm criteria? I wondered that when I read the article – is it possible to know by yourself? Do you pay attention to your body and then know when you pass from push over to crash? And how do you do when the push-to-crash depend on that kind of stress that is hard to avoid, like strugggling with financies for example because that make me crash sometimes.

Thank you and have a good day!

Confusing the first question – I mean don’t you get the same heart rate monitoring from both?

Hi eva – some heart rate monitors are a chest strap plus wrist display (the strap measures, the wristband displays the reading), while some are just a wrist monitor-cum-display. The latter are less accurate – I think Staci Stevens (or Connie?) recommends against them.

Then I know, thank you Sasha :-)!

With the wrist watch, you have to make contact with the watch with your other hand. By the time I stop and make contact my pulse has already slowed. I never could figure out how to have it alarm without having to initiate contact with the other hand.

With the Timex Ironman (women’s model for me) the watch is worn on the wrist and the chest strap around the chest. Of the things I have tried this is the most accurate but not perfect. I have to dampen the two electrode bands to initiate contact and to get accurate readings.

I just used the heart rate formula mentioned here.

220 (max heart rate) minus age multiplied by .6

This plan does sound really great, especially since those breathing regimens can help people with say fibromyalgia regulate their stress levels. In normally healthy patients, the white blood cells are responsible for producing a number of unique proteins. However, research has shown that people with this medical condition actually produce less of two specific types of protein (chemokines and cytokines). The lack of these proteins suppresses the immune system, which explains why fibro patients are so susceptible to varying levels of stress.

My breathing changes when I am over my anaerobic threshold. I found that all I had to do was slow, stop stand or sit and the pulse rate came down very quickly. I don’t feel the need to use the monitor often now, but I did all day at first to see what raised my pulse rate.

I used the standard formula, but my multiplier was 60% and not the 80% that the healthy person would use. 220-age x 60% as per Dr. Charles Lapp and Bruce Campbell. http://www.cfidsselfhelp.org/library/pacing-numbers-using-your-heart-rate-to-stay-inside-energy-envelope

I like the idea very much of improving one’s breathing, and now try to use that technique during meditation. I also have timers that tell me when to stand up and move when on the computer, or doing anything else sedentary. It seems that sitting too long is particularly bad for people generally.

I try to stand up and move every 30 minutes. If people are not too severely affected, I would guess any sort of movement would be good. I feel a change in position must help my heart to beat bit stronger, and move my organs around.

I have to lie down all day. I’m rarely able to sit or stand, except when I recline at 45º to eat my meals.

Does anyone know what I should do when my heartrate goes over 90 bpm, which is my anaerobic threshold, as defined by Staci Stevens?

It often goes over 90. I can’t stop and sit down or lie down, because I’m already lying down.

I’m in the same place you are Rebecca, I can hardly move out of bed, stand or get to the bathroom. Are you sure your anaerobic threshold is 90 bpm? I believe we must have a substantial lower threshold than the not-so-severely affected patients. I have been bed-bound for over four years and have a nagging feeling I’m overdoing things even if I’m really mastering the pacing now. I suspect my anaerobic threshold is lower than I can bear to acknowledge.

Anyway, my tachycardia is now under substantial more control, and the reason is beta blockers. I started at ultra low doses of propranolol four months ago. But the significant effect came firstly after I reached a «normal» dosage, and I am now at the maximum dosage (Inderal Retard 2×160 mg per day – 160 mg in the morning and 160 mg in the evening). The secondary gain of calming my heart and relieving the tachycardia is that my head- and facial pain is not so severe anymore, and my exhaustion is milder. I don’t experience PEM as often as before. This is a new life, although still in bed.

I took Workwell’s CPET a few years ago and learned that my anaerobic threshold is 84. I am bedridden only about 20-25% of the time (even if I only make it to the sofa). Good days are when I can cook a simple dinner or do a load of laundry, so I think my situation is less severe than yours. Sorry if this is bad news to you. I probably exceed my threshold frequently, and I think it’s affecting my baseline. I plan to get an HRM and put more effort into pacing.

Slow, diaphragm breathing while focusing on lowering my heart rate has helped. Good luck!

Hi,

After numerous attempts at exercise over the past years and through much reading, I have also become aware of this approach in trying to improve my health. I am currently up to jogging but making sure I keep below what I know to be the distance or pace which tends to set off the worse symptoms of my CFS.

I have a heart rate monitor watch which I can use but I have not incorporated this into my routine yet. My question is: How do I determine the exact range which sets off these problems? I can generally tell physically when my body has hit that anaerobic zone, as I feel a much greater struggle to maintain the level of exercise I was doing minutes/seconds before and I will pull up very poorly the next day(s) if I have blown my ‘energy budget’. Is there something which highlights this on your heart rate meter? Does it spike ? Is there a way I can get these tests done in my city and if so, could they be put into writing form so I can pass them on to my doctors?

Kind regards,

Lachlan 🙂

I do not think it is that simple, sorry!

Probably not, but at least it makes me feel like an active participant in my recovery.

This case study is fascinating! I wonder how much of the improvement is attributable to avoidance of anaerobic activity versus adding the low intensity ‘short duration’ endurance exercise, some mild resistance training and gentle stretches. I think the exercise portion of this protocol serves primarily to prevent further atrophy while allowing the body to recover from the anaerobic overloading we subject ourselves to while trying to improve our conditioning. Is it a disservice to our illness to call it an exercise program, so our main stream docs can continue to assume that exercise is good for everyone? To me this is not so much an ‘exercise program’ as it is a very strict (anaerobic) activity reduction program. Without eliminating the anaerobic activities, the exercise portion might not provide any benefit at all. But it is exciting that they have found something that seems to work for those of use who are not bedbound. Now if we could all just figure out what our anaerobic threshold is! I have found, using a heart rate monitor, where I start to feel yucky. That might be the anaerobic threshold – maybe if I subtract 10 heart beats from ‘yucky’, I might have a safe setting for my monitor.

for now, please just send me any new posts, thanks! udy

Please vote for research funding award

Please repost on Twitter and Facebook

Many thanks

https://www.directdebit.co.uk/DirectDebitPromotions/BigBreak2014/Pages/CauseDetail.aspx?CauseId=381

Great

While this is great I think a limit is people have to be well enough to undergo the excercise test. When I underwent a 2 day CPET I was already housebound and the test set me back… well its been 3 years now and I am still bedbound. You also have to be able to stay under your threshold and do some sort of excercise which for bedbound patients may not be possible.