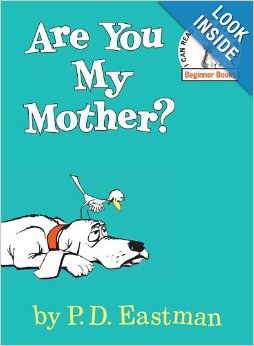

Are You My Mother?

One of the first books we read to our sons was by P.D. Eastman called Are You My Mother? A mother bird, wearing her white polka-dotted red head scarf or babushka as a symbol of family life, leaves her unhatched egg alone in its nest while she flies away in search of food. Alas, before she returns, the baby bird pops out of the egg and looks around for his mother. My little readers/listeners cheerfully suspended their disbeliefs: Of course it’s a little boy bird and of course it knows it has a mother. And, of course, he will hop out of his nest and search for her. They never even considered that he might look for his father.

Anyway, the baby bird plops out of the nest and walks away to ask everyone and everything he meets if he/she/it is his mother. A kitten, a hen, a dog, a cow, a car, a boat, a plane, a steam shovel. At the end, the steam shovel, which the baby bird calls a “snort,” lifts him way up in the air and drops him back into his nest, right when the mother bird returns with a big fat worm in her mouth. “Do you know who I am?” she asks. “Yes,” he says. “You are not a kitten, a hen, a dog, a cow, a car, a boat, a plane, or a snort. You are a bird, and you are my mother!”

Okay, maybe she shouldn’t have waited so long to forage for food that her egg hatched in her absence, but, hey, we still have that last picture of the baby bird cuddling under the warm wing of the mommy bird, her babushka tied under her chin, her eyes closed, her face serene and self-satisfied. Nurturing to the bird mother and her fledgling seems pretty simple: supplying food and comfort and safety. We assume that the mother will teach him how to fly and live like a bird, but the moments captured in the little story focus on the return of the mommy to the nest with her big fat dead worm, her babushka, and her cozy wing.

My own parents made money for the essentials. We had food and clothes and shelter. But nurturing? A wing and a babushka? My mother was a high strung bird with spiky feathers and intense beady eyes, always out foraging. My dad could be sweet and affectionate though he mainly waxed floors for a living, took naps, and raged at my mother. But then there was Shirley, our housekeeper/nanny for most of my grammar and high-school life, a consistent presence for my brother and me, from breakfast to dinner-time every weekday. Shirley was a fat old bird with soft fuzzy gray feathers and mild, kind sleepy eyes. She let me sit on her lap with a tweezer and pluck the black whiskers sprouting from her chin. I set her hair with rollers and then brushed it into waves. On rare days I was home sick, I sat at her side on the couch and watched soap-operas: Search for Tomorrow, The Guiding Light. She carried tea and toast up to my bedroom. She had grown children of her own, of whom I was jealous.

Except for Shirley, I think I mostly raised myself, learning about the world and its social requirements by intently watching friends and their families, learning about menstruation from pamphlets, about cooking from cookbooks. I was no recluse, had friends and loved school, but in my deepest places, I was lonely and needy and sad.

Family

I married at 20, and Steve filled up much of my emptiness. In my mid-twenties, along came these two beautiful babies, 22 months apart. How was I to provide the fullness for these creatures who demanded my every moment, since I was still wandering through the streets asking, “Are you my mother?”

But I adored the boys and as they grew older, I think (read: hope) I gained enough empathy to provide safety, security and support. If nothing else, I liked to hug and kiss. In retrospect, I see that I did get pieces of love from various non-mother people, from the kitten, hen, dog, cow, car, boat, plane, and even from the steam shovel. There was my dad in his more playful moments, dancing around the dining room; Shirley with her big soft bosom and whiskers. But I also ran into a teacher here and there, some high school and college friends, and definitely Steve, who showed me I was someone of value.

Mostly, however, I took care of myself.

1999. Flu shot. CFS.

“I was supposed to figure all this out on my own”

Fourteen years of illness, fourteen years of wandering in the desert, searching even more desperately for deliverance, fourteen years of pleading, “Are you my mother?”

My mother was not only unavailable; she contributed to my misery because her hypochondria and pathological nervousness meant I could tell her nothing. My children had their own lives and dismissed me with, “Mom, you’re becoming Grandma Helen.” And my beloved husband, who was struggling to adapt to this stranger I’d become, took over household chores and responsibilities but felt too overwhelmed to research the disease, to look for explanations or treatments.

I was practically a corpse whose brain and limbs had been pulverized in a blender, with my once caring Dr. Kallich flicking me off her shoulder and other doctors telling me to just wait, I’ll get better; I filled with terror and depression and could neither focus my blurry vision to read without dreadful headaches and nor make any sense out of words anyway; and I was supposed to figure this all out on my own. Understand. Make plans. Seek solutions. Open to page one.

I was and still am convinced that if our roles were reversed and Steve were the patient with this severe mysterious illness, I’d be Googling my days away. I’d be in the library and on the phone with his doctors and with whatever resources I could find. I’d naturally and deliberately walk with him into the doctor’s office on all visits, rather than asking, “Do you want me to come in with you?” I’d sit next to him and hold him and ask him questions about his condition. Men and women again. Mars and Venus.

So another complication adding to my misery was the roiling mix of resentment (damn it why can’t he focus on me and find a doctor and pick up the phone and make an appointment and tell me what I must do) and guilt (he’s going shopping and making dinner and doing the dishes and how can I be so immature and resentful I’m a real selfish shit). CFS turned me back into the little girl, lonely and needy in a dangerous world, seeking safety, care, warmth, rootedness. A grown-up who would pour his/her soul into me.

Did my early family life make me even more fragile than I might have been with a history of nurturing love? Who knows? Other sufferers tell similar stories of “the lonely, disparaged country” we with CFS live in, (Dorothy Wall, Encounters with the Invisible”, p. xviii) and there’s a lot of talk about nurturing the self, but I have yet to read about the extreme demands for perpetual nurturing on caregivers. Or the sick one’s actual need for infantilization. Poor Steve.

Thankfully, I’ve reached a clearer place where I can fend for myself much better, probably as the result of the antidepressant and the steep drop in stress after the deaths of my parents and my brother David’s move to a group home, and, most importantly, the time-outs Steve and I take to talk. Time, too, must be a factor.

Friends

But, unlike too many CFS sufferers, I have been blessed with loyal, patient and caring friends.

In his forward to “the facts: CFS/ME”, Professor Anthony J. Pinching says

CFS/ME. . .is a common, beastly, variable, confusing, invisible and pervasive illness. It profoundly changes just about everything in the life of an affected person, as well as in those around them. . . other people seem to react differently. . This illness doesn’t readily fit some prevailing medical or social paradigms. This leads some people to diminish, deny, or even neglect those affected.

A commenter on one web site describes her CFS and the reactions of her friends:

And the word “fatigue” is a mischaracterization. . . If one doesn’t have it or live with someone who does, it’s very hard to understand it. My long-time friends don’t even get it. Some think they do but they don’t. . This is so frustrating. (Kathy D.)

Other web sites describe friends who disbelieve and lose patience with CFS sufferers, blaming them for being lazy, or like my sons, exaggerating minor ailments. I too have encountered people who insist, “How ill can you be when you look so well?” They criticize and challenge and dispute everything from my symptoms to my treatments : “Yeah, I’m tired too. Just take a nap,” or “Go jog around the block. You need exercise and fresh air.” “You’re not taking Vitamin D? Oh my, that’s not good.”

They assail me with skepticism or offer anecdotes of miracle cures from acupuncture, from Chinese herbs, from hyperbaric chambers, from rife machines, from iodine treatments, from mangosteen or Noni juice, or apple cider vinegar. Though I’ve tried just about everything, I start perseverating: Maybe I should find another doctor for the treatment or maybe I didn’t stay with it long enough or maybe or maybe or maybe. . .

But I’m far luckier than bloggers like “hurtingallthetime”: “ive pretty much lost all friends from when i became ill…lost my job..and stay in house majority of the time…it is very isolating and hard. . My friends have been caring, helpful and understanding.

They regularly drove me to doctors when Steve couldn’t: to my Lyme doctor in Caldwell, New Jersey, to the witch doctor in Denville, New Jersey, and to the Chinese Herb Acupuncture Guru on 70th Street in Manhattan. That’s unbelievable. These trips could take most of a day– an hour there, at least an hour or two or even three in the office, another hour home. They packed lunches, brought their books or went shopping, and stayed cheerful and supportive.

They feed us. We’ve had challah and roast chicken on many Shabbat dinners with Karen and Steve. When Steve leaves on his adventure trips, friends watch out for me. Mort makes the best baked salmon, barbecued pork chops, applesauce and tamari chicken. They include me in their restaurant outings.

They always understand when I have to cancel something at the last minute because of a relapse. Their responses are supportive and consoling. (“Oh, I’m so sorry. We’ll really miss you, but please, rest and feel better.”)

They call to see how I am. They listen to whatever I need to tell them and keep offering their services. (“Do you need anything from the supermarket? The drug store? The farmer’s market?”)

Whenever my neighbor Marjorie goes to the Pennsylvania Dutch Farms near Princeton, she brings me a chicken; she baked me black bean brownies without sugar and a pumpkin pie at Thanksgiving.

Laura drove to Highland Park from her apartment in Manhattan to get me and drive me back into Manhattan for a writing group session.

When I’m flat on my back, they stop by for short visits. They bring bagels.

When we stay overnight with them at their home on Long Beach Island at the Jersey shore, our dear friends and ex-next-door-neighbors Richard and Nancy are always solicitous and cheerfully supply whatever I need, from seltzer to gluten-free crackers to quiet in the afternoon when I nap. I never feel discomfort or uneasiness. We’ve been on two cruises together since I’ve been ill, and just celebrated our 50th wedding anniversaries together at a joint party. It was amazing – and they did everything they could to accommodate my needs and feelings.

I love my friends.

Yet isolation is still one of the most profound results of this disease, for even when I’m with them, too often I feel desolate, and there is nothing at all they can do about it. They have rich, full lives while I live with daily deprivation and loss. But I know they are aware of this and empathize.

The concept of feeling “better” is a real bugaboo. If I say I’m feeling better, some inevitably assume I’m back to normal or maybe even cured. It’s difficult to face their expectations and explain again that, in the words of Dorothy Wall:

To me, better means this: In year three, on my absolute best day, I managed to walk eight blocks, a half a mile, but I couldn’t repeat this distance again, and the next few days I was unable to walk at all. . . people who are ill as long as I have been don’t get all better.

Encounters With the Invisible, 236

The gap between their assumptions and expectations and my reality is depressing and even embarrassing. It’s so hard for a healthy person to understand an illness that is mercilessly relapsing and remitting.

In any case, even the most compassionate of friends can’t give you back your life: your stamina, your job, your former sense of self. They can’t be there every lonely minute, nor do I want them to be. But they can continue to value and appreciate me as a person, making me feel as if I still have a place in the larger world.

And my amazing friends do that.

Thank you Carol (and Cort for printing Carol’s story)

This is well described, well written – and well timed for me personally.

I will pass it around to my many ME/CFS contacts whose lives are also terribly isolated as mine is, and meditate on it myself, for some aspects of it ring true in my own life. eg: “I love my (remaining) friends” (and some of my family!); that said, about half my 10- to 15- year long friends abandoned me utterly as I went into the most severe phase of illness a dozen years ago; “the concept of feeling better is a bugaboo” – yes, this is a constant problem even with those who think they know me and think they know my situation. Maybe they just want so badly to believe or hope that the little improvement means more than it does. Whatever the case, it causes me trouble and needless social stress that they don’t get that the relationship of symptoms and severity to improvements is a log scale and that most days, I am being “hit over the head” by that log. After two dozen years or more of illness, and a dozen years now in the severely ill category (20% or often lower on DAvid Bell’s CFS ability Scale), I am STILL at the bottom of my “Log Scale”, and the amount of “better” it will take to get even one little rise on the Y axis, to the level of function where I could make my own supper (I used to love to cook), or take a needed shower on the same day (or in the same week!) that I check email, is YEARS of “better” in about 10 arenas of symptom management. Most times the friend is just hearing about a small personally meaningful improvement or even just an aberrant “freebie” in one arena – never mind in all 10. And the price for celebrating or acting on that improvement can be months or years of worse health.

So, after so many years, the effort required to patch and fix and reset the constant misunderstandings are making me lean toward sticking to a stock phrase “I remain severely ill and housebound, but would love to hear from you personally during a time when I am well enough”, thereby sacrificing my hope of celebrating any small victory with someone I think “understands” – yet another thing I have to face alone in this life. If I had cancer and low platelet count, a stroke I was recovering from, or MS and the results of an MRI or clot blasting drug looming, dozens of people – friends, cousins, family, and a wider audience of internet “friends” – might be hanging on the edge of their seats on a social media site, cheering me on, listening to me list my hopes and fears if i could write at all, writing the reports for me (without false hope or distortion), and waiting to see whether the count went up sufficiently, if the MRI was positive, if the new drug helped… will she survive, will she get better…. they would all have some basic education about the illness, feel empowered and socially obliged or encouraged to inform themselves, and even to try to help by raising money or something specific. But with this illness, when I am steeped in abject fear due to dozens, hundreds, or thousands of painful sleepless nights filled with whole body pain, weakness, shaky muscles and amplification of noise and light, chest pain, flu like symptoms surging and persisting for weeks (with the same molecular pathways as if you had cancer), have the symptoms of a stroke or MS, the illness level of AIDS or a cancer patient during chemo, and it goes on for YEARS or DECADES, otherwise-caring people may say, “just stop talking about your symptoms, I am tired of hearing about it.” or “you are boring me” or “you are depressing me”. So I have to face the hellish symptoms as well as my tiny improvements alone while my “well” social circle abdicates its natural responsibility to be responsive and not to deny that my suffering is valid, real and just as scary as that of others who are in real medical duress like I am. Just because i don’t get help or it never ends, does not mean it is less difficult to endure, less worthy of others’ care and concern.

“They assail me with skepticism or offer anecdotes of miracle cures” – yes, that went on for years and still happens regularly. Worse, they don’t care or listen at all… and after decades some still think I am magically going to get better (and have sufficient money ie a job, a home of my own and no need for their physical help or moral support), although none of them are volunteering or running ME support groups, pushing for research funding, donating to ME research groups, doing ME fun runs, raising money for research or worst of all – even sure what ME/CFS is and what the implications are to the person or to their relationship with the person. They don’t understand or take ownership of the fact that I can’t get better because i have no treatments available to me which are science based, studied in real research studies, and paid for by universal health care (Canada), and medical care for this illness is stuck and spinning its collective spokes at “Victorian Era” level of care (or lower, since the Victorians at least understood that you have to rest and take certain procedural measures like pacing for eg TB management, and, avoid exposure to X or Y when ill), and that we need public outcry and solidarity to change that. They do not have sufficient awareness that we need their help – and that we are getting sicker because we don’t have it. While we must always be given the floor to speak for ourselves, it must not always fall to grievously ill desperate, frightened, ME/CFS patients to struggle (and it is a struggle just like it was for AIDS patients and their loved ones in the 1980’s), to make change happen from their beds. Sometimes I suspect that those who have known me through my many long years of advocacy seem unaware of two things:

1. I am at times legitimately frightened for my future, my life and well being

2. I endure the same ostracism others do, and it may be worsened by my role as a long time advocate for better care and more research.

“Damned if you do, damned if you don’t”, says one very ill ME CFS friend fighting a landmark legal case, always says. Don’t show your face and you don’t exist (and don’t get any help), show your face and you must not be that sick (and you may not get any help).

Like Carol I have endured ostracism, antisocial reactions, blame, disrespect, condescension, verbal abuse, spurning and dismissal of my situation and symptoms. I am thinking of scenarios where it came from random members of the public, administrators, office workers, cashiers, librarians, cafe owners, clinic employees, too many doctors to count, sadly some inlaws or others who know me well and should or could know better. All slagging my integrity, impugning me for needing help, co-operation, kindness or an exception, or for having my circulation, energy or memory conk out on me and needing first aid – and being unable to talk them through it. Or for being irritable and distressed because they woke me up for a visit (never do this, family) and brought a one year old along who I had arranged to see when I had been up for hours, and sufficiently managed my symptoms.

Daring to go out in public when so ill but “looking fine” causes insecure or mentally imbalanced “working” people to attack, or to abuse what social power they have. Daily management of symptoms even in the home (I am 90% housebound) requires superhuman (and inhumane) restrictions which can be crazy-making and upsetting to family who do not see – and some do not handle it with equanimity, instead attacking the sick person for needing what they need. Having multiple chemical sensitivities on top of ME/CFS is particularly isolating. Some people take it personally that they need to be completely fragrance free (using products the person in question can tolerate and has specified) to come into the home. Others stay away, making for less love and support not only for me but also for my dear parents, my ageing caregivers. Still others are passive aggressive – leaving me out of discussions about when they are coming over, thereby jeopardizing or sabotaging my careful pacing, trigger avoidance and symptom management. Others do it by denying the reality of the need for the various treatment and management protocols (none of which i personally like or would do if i were not desperate to control terrible painful frightening symptoms which will only get worse if i neglect to attend to this!) not communicating, and not offering to co-operate when making plans to visit someone else in the house (if you do not live in your own home, you face this added stress). I have watched (and still do watch) as those who could have helped me did nothing to correct, guide or stop these ignorant people from victimizing me and those in my situation.

I realize the most constructive thing to do to get uninitiated people motivated to help or become aware, is to laud the good actions, deeds and works of those who are helping – so despite this “rainstorm” today from my battery (sic) of personal experiences, that is the path I also choose, as a rule.

Carol, I would like permission to use portions of your article in caregiver/health aide educational materials I will be using in communications with provincial health aide educational organizations being given education about caring for the severely ill with ME and MCS – how do I email you to get permission?

Severely ill with ME/CFS, MCS, chronic Lyme, and an orthopaedic pain syndrome for 30 years.

And now for the other side of the coin:

This is to embellish on “I love my (remaining) friends and my caring family members”:

Here’s to the people who have been so considerate, kind, caring and selfless in the face of my chaotic, long-term, life changing illness. Here is to friends who miraculously still want to see me and know me as a friend, even though nothing is the same any more – I am not free to be the same outdoors-loving, music-performing, intellectually astute, upbeat instigator of many a good social occasion, adventure or deep sharing; even though i can no longer be the who plays with their kids, walks their dog, house sits or helps build the shed, joins them at a social gathering or hosts them for a meal;

Here is to those friends, who are willing to hold out for that rare good moment and who have come to see me, to cook or care for me when I have needed respite help, which incidentally i cannot get from my local community supports services due to their un-fulfillable criteria and their low available staff. (Who among us can reasonably give three months’ notice of needing respite care?). To those who admire my courage; roll with my unpredictable life and schedule; who support ME/CFS research or sign a petition, who opt to buy Christmas Cards from Invest in ME (or do other fund raising), who take it easy on me with regard to expectations around gift giving and other things I cannot well afford, yet who can accept a gift from me graciously.

Here’s to one dear couple, old friends I have known since before my illness, who live practically scent free, enabling me to come to their home to visit despite my severe ME/CFS and severe Multiple chemical sensitivity. Here’s to a friend (actually I have several who do this – bless them – ) who is so conscientious about how ill my scent sensitivity can make me, she takes care not to come over on days when she’s been exposed to scent from other volunteering she does with the public. Here’s to my kind sister who has bought me clothes, made me nice unique practical clothes I wear daily to keep me warm while i convalesce. She has even helped make a special (and also very nice looking) adjunct to my black-out blinds in my bedroom, to help block the light so i can sleep despite my daytime sleep requirements! Here’s to her ultra considerate actions when she comes to visit, always taking care that her dogs do not wake or disturb my painful and fatiguing auditory hypersensitivity; she has helped me shorten writing and articles, helped me make a business card, and helped me in so many other ways i can never repay.

Here’s to friends near and afar who remember me, contact me spontaneously, taking some of the burden off of me to keep up communications when (because) i am not able, or less able than ever before in my life. Thanks to them for keeping an eye on how i am doing and not forgetting me despite very busy hectic lives. Here’s to anyone who asks me how i am and sincerely wants to know. It means something when someone asks, even when i don’t have any news or hope of a cure. I feel included and “seen” as a person.

Here’s to the friends who have driven me to an appointment, accompanied me to a crucial meeting, taken me for a rare ride in the country or kindly taken the time to visit me (with the understanding of how profoundly difficult it is for me to visit them or go out anywhere), and who, all the long years of this Unique Hell, remained respectful and cheerful, loyal companions even when i know i have not always been the best company due to pain and the unpredictable problems with concentrating and remembering.

Saw my disability and illness without losing sight of the person who was still there.

Valued what i still had to give instead of focusing on what i could not do or be any more.

Interacted with me as an equal adult when it came to our discussions and our hopes and fears, different though they may now be.

Here’s to the neighbour across the park who despite her own heart condition and type 1 diabetes, cheerily and kindly gives me respite help with cooking and some basic household chores, and is at times a listening ear for my strife – so kind!

Here’s to the friend with a chronically ill husband, and two ill parents, and 2 dear children to care for, who generously rallied in my stead, literally being my hands and feet when i could not attend an awareness march; another who wrote astute and caring articles to publish in church newsletters or elsewhere; helped me edit my own writing; helped me think and make advocacy decisions that would ultimately help many others; were patient and kind when my illness was costing them extra time or perhaps other personal sacrifices; made efforts to include me from afar when i was sad about being left out of social gatherings with mutual friends; sent me cheer via email, snail mail or other means; gave me photos of themselves or their kids; made a kind effort to keep me in their family’s thoughts and minds so their kids would know i was beloved and valued despite my absence; giving me spiritual support and showing true principle and selflessness.

Seeing me for who I am and welcoming the love, personal attention and gifts i had to give.

To my caregivers, my wonderful kind helpful senior-citizen parents – for giving up some of their personal freedom and part of the use of their home to give me somewhere safe, affordable and protective to live where i can better manage my MCS, as well as the severe ME/CFS; for keeping house, cooking and shopping , providing a quiet, scent free place to live, and often keeping me company….

to those who are helping me plan for my shaky and uncertain future (when I will be alone and without a home of my own and unable to afford care.) ….

I think of the Joni Mitchell song, Amelia, where she sings, “this is how I hide the hurt, as the road leads, cursed and charmed”. Cursed, and charmed – yes that is how it feels being all at once surrounded by scorn, indifference, ignorance, and even contempt I named in the previous response to Carol’s article – yet also paradoxically being adorned with care, love, regard and support from such special and wonderful people as these. I am blessed indeed to know them.

Here’s to those who have shown me or those like me, living in the Storm of ME/CFS, their caring and consideration, kindness and compassion. Focusing on them, on their good hearts, and the blessings they have brought into my life, is how I overcome the hurt this horrible situation has brought on.

I just thought of a succinct way to put all of this, after all this writing (which I will pay for I am sure):

“Some people drive me too hard, some drive me to despair and some, bless them, offer to drive me to appointments.”

I’m glad you have such good people in your lives, in spite of all those who are unresponsive and insensitive. Here’s to the ones who drive us to appointments!

“Cursed and Charmed” — and at the same time. It’s all so complicated.

Thanks for sharing your story. I’ve had CFS for 3 years with symtoms even earlier. I have had the opposite happen in my case. I’ve been very isolated and it was almost as bad to deal with at first as being ill. I got used to it over time and with help from a therapist. I found a therapist who had healed from CFS so I trusted her. I could go in and lay down, cry, could barely walk in most times. It makes me happy to hear that you had a better experience with friends and family during your illness. It’s what I hoped and figured would happen when I became ill. I’m on a upswing now though and hope that I stay on it.

My therapist is an occupational therapist who does a process called Somatic experiencing. It deals with healing trauma in the body, mind spirit. It helps the nervous system calm down. I had a traumatic childhood as you did and I’m having to go deep. I didn’t know it affected me as bad as it did and I’ve been in therapy a lot in my life. I just couldn’t handle stress anymore on any level. Done! It’s pretty much PTSD. It has helped me be able to drive again. Go by myself places ect. Not a lot yet but more and more. I wish you well and again thanks for sharing!

Excellent piece Carol.

A note for Carol and Linda:

I am still too vain not to try to look well when I go out. However, I have been thinking recently that perhaps some of us might want to practice the techniques of stage make-up to do away with those remarks of “well, you look so well.” Why not? It might be good campaigning to go around looking sick. Pale, greyish skin, shadow under the eyes, rouge around the nostrils and flaky white stuff on the lips.

Ha! I’ll bet there are post-Halloween sales on zombie make-up.

Carol, you had one heading “1999, Flu shot, CFS”

Do you link your onset of cfs with a flu shot you had? I would be interested to hear your thoughts, as I am in a work care legal case as I had a flu shot at work, 2007, and have gotten progressively worse since then, bed ridden since 2010.

Like to hear your theory, use my personal email if you like.

Kellie

Hi Kellie,

I was first diagnosed with ME in HongKong in 1985 (shortly getting a travel vaccine) along with many of my travel abroad classmates. I had a difficult 3 years but did improved well enough to begin graduate school the winter of 1989. Shortly after classes began I was notified of that I would have to retake all childhood vaccines or provide proof of prior inoculation. My records were packed 3000 miles away. I had not looked at the shot records for years and was not sure were to tell someone to look so I agreed to the shots offered at the school clinic. I remember the next day I felt off and continued a steady decline over the next few years. By 1993 I was confined bed in a darkened room and total disability. By 1995 I had improved enough to be able to take bus to a museum 1 day a week by myself to help with simple tasks in the conservation lab. Since, there have been ups and downs, some years better than others including a 1998 bout with acute Lyme (encephalitis near my brain stem) and a couple of years were I felt “cured” This year was a “spectacular” reaction to a tetnus shot, and most recently other powerful reactions to the flu shot and pneumonia vaccine. No more preventive shots for me. Have you seen the pleadings of case that prevailed last year against the HHS fund. Best Wishes, Lolly

Anecdotal evidence indicates that vaccinations at times have preceded the onset of ME/CFS, yet there’s little research that explores the relationship. In my case, I think the flu shot was a precipitating factor. It was black and white. Healthy. Flu shot. Sick. Maybe I’m guilty of the logical flaw post hoc ergo propter hoc (after the fact therefore because of the fact), and maybe it’s just coincidence, but flu shots affect immune systems and my immune system was affected.

Thank you. Many things resonate from both your posts; especially, my deep gratitude for friendships, and family, yet always secretly, simultaneously, wishing they will stop their lives and just do MORE (without even being able to instruct them in exactly what a helpful MORE looks like. Because I have no energy to instruct! How unfair of me. I am wishing for mind readers ;)).

Quick note, question, perhaps somewhat off topic (apologies if so):

Carol you mention “chronic” lyme.

Do you feel–and please other commentators, chime in — That M.E. and Lyme are mutually exclusive? (i think, at least acute lyme technically is considered exclusionary of ME, by the Canadian Consensus Criteria etc) Or do you conceive of it as Borrelia/Lyme triggering the ME/CFS? Or perpetuating? or opportunistic infection from weakened immune system?

Complicated subject, and not entirely sure it matters (well, does for treatment)–But curious to your thoughts on this.

@Cort: I wonder your thoughts on this, too.

Thanks All, for your energy in sharing your thoughts.

Htree

I am certainly unschooled in the literature about the relationship between Chronic Lyme and ME. All I know is from my own experience and some reading. I was diagnosed with Lyme and Bartonella around 2002, about 3 years after the onset of my illness. The intense antibiotic treatments for about 3 more years did not result in symptom improvement — just Candida problems. I don’t know much about the CFS/ME Lyme connection or mutual exclusivity.

I know the definition excludes other illness, but how silly is that. If you have ME/ CFS long enough you are bound to get all kinds of things. I developed acute Lyme 13 years after my 1985 ME diagnosis. My physical reaction to the Lyme Infection was super charged as almost every known symptom for Lyme appeared including encephalitis. We know that the Lyme had not yet had a chance to become chronic because of the type of anti-bodies I was carrying. I was hospitalized, and fortunately included in NIH studies, and did receive very aggressive IV antibiotic treatment. For a number of years I felt “cured” but eventually back slid …. thank heavens, not to the extent of the early ears.

So well said by both Linda and Carol. Thank you both for taking the time and energy required to write about your journeys so well. I do believe that you have described the life of most CFS’s sufferers. Truly, what a strange disease we all have. What a weird thing to not only live with an illness that is as devastating as this one is, but then to have to be in a postition where we are constantly fighting to be heard, to be understood, to be validated. I have just given up on making new friends, and the few that I have, I just do not talk about my illness anymore. To family, pretty much the same thing. It takes too much toll to try to get people to understand. They really never will, and is it so important to me anymore that they do? No.

I relate to this piece so much. Thanks for writing it! I had a mother who was unable to take care of me growing up & I largely had to take care of her. So when I got sick I really felt that loss & emptiness of not having a caretaker to nurture me through those first couple of years of illness. So a lot of emotional baggage was included with the intense physical sensations of feeling so sick. And I so relate to your anger, sadness & guilt about your husband’s role. After 10 years of illness, my partner has never once looked up medical info about my illness or offered help in trying to figure out treatment. This hurts me so, so much. But I always feel guilty thinking or saying this because he’s the one who has to work, pay all the bills, do all the shopping and cooking. I’m trying so hard not to take it personally & to appreciate what he does do but some days it really bums me out that he’s not fighting alongside me in trying to figure out what treatment to pursue. My friends are great but they are all busy working and tending to their small children, so they aren’t very available. Sometimes when I feel very alone, I question if my friends even care about me anymore. But I have discovered that this is more fear than reality. I think they really do care but they are just overwhelmed with the demands that work & family put upon them. So I am getting better at not taking their absence personally. But of course that understanding doesn’t make the loneliness go away but it makes the days slightly less painful.

Like you, I find I have to sensibly (not always possible) evaluate my situation. I can become over-reactive and super self-pitying at times, and that’s when I have to stop and take stock. It’s hard to be empathetic when we are so sick, but that’s what we expect from others, and I know I have to work on understanding how difficult it is for my husband (especially), for my sons, and for my friends to deal with such enduring illness.

Carol and Linda. Both great relatable testimonies to how I feel. With the exception of my loss of all family and friends after 2 decades of ME/CFS , Fibromyalgia & chronic Migraine, spinal rumors etc.

My mother is a narcissist, my father was a depressed & violent alcoholic. I grew up unloved & in constant fear. I wasn’t unprepared emotionally to be this sick for this long. The last couple months I think of suicide daily. And I know before the end of the year, I will eventually give up.

I’ve reached reached out for this last time this week. To my family “You can control your illness with your mind if you really wanted to” & “just stop thinking negative thoughts” “I thought you were better ” ” stop feeling sorry for yourself” ……when I told 3 people I didn’t think I could face another Xmas alone, all 3 responded ” You’ll make it”.

The most pain I feel is the loss of my granddaughter. Who I haven’t seen in 2 yrs. she’ll be 10 in January.

I know my family is dysfunctional but not one of them in all these years have read even the description of these illnesses. I was the caretaker of this family up until I was 95% homebound the last 3 yrs.

Anyway, my point is, there is no reason to keep suffering.

Even Cort said he’d help me with an idea for this isolation. But that was over a week ago and he hadn’t responded to my texts or FB msgs begging to know what his idea was.

I’m invisible. I’ve felt rejected since I was a child. And now I feel like that helpless child who has no where to turn, except to disappear.

Be grateful if you have human contact with anyone. Because going weeks without hearing a human voice is maddening.

The insomnia, the pain, the fatigue, the nausea, the constant freezing or burning up, the vision loss, the balance loss the depression, blah blah blah. Too much for NO reason.

Good luck to you all. And be happy if you have 1 person who loves you.

Ohhhh…Dear Invisible.

I feel your pain. Is there something I can do? I am not so eloquent as many but I do care………it sounds like you are in such agony and I do want to help.

Please know there are people who care deeply for your situation. I hope you can hang in there.

Blessings

I think of my early years in this illness when my only solace was the thought of suicide and oblivion. No one can really understand the depths of another’s pain, but I remember every day as too difficult to bear. I unsuccessfully tried every single anti-depressant out there. . .and finally was able to take Lexapro, which has definitely helped to pull me out of those emotional depths. I still get depressed when the disease does its worst, but my earlier suicidal thoughts return only infrequently.

Good therapists have helped. I am lucky to have health insurance.

I also find writing a way to some relief. I can see from what you’ve posted that you have a lot of stories to tell, even if your audience is yourself. Keeping a journal can be very powerful.

I agree with Dawn — many of us care about you and your situation and hope you find ways to cope.

Good luck to you too Invisible! It’s so hard to know how to help without spouting platitudes. Heaven knows we’ve all probably heard so many “helpful remarks” that just make you feel worse. It’s been good for me to find an online community that I can relate to with so much of this that healthy family and friends just can’t. Hope it helps you to know that others care and can relate, even if we can’t show up at your house with a meal.

I think that Carol’s idea of writing your stories is a good one. You are able to express yourself much better than I am when I’m all the way at the bottom. I hope you won’t mind me saying a prayer for you!

Please also don’t forget that each state has crisis hotlines. I’m sure there’s one in your area with people who are trained to listen and help. I also found this site: http://restministries.com

which is Christian based but seems to offer help to all with chronic illnesses.

Yet another reminder of why this site is so important to have and important to me to read. I love(d) to write but I just don’t anymore, as I’m less confident of my intellectual abilities and fearful of the consequences of so much brain use on my daily stamina. So I thank you Carol, Cort, and others who take that risk and spend the precious energy they do to write here and maintain our sense of community.

Carol, you are fortunate, most of us with this horrible disease, do not have the proverbial cast iron stomach. Therefore, some, may have all the other symptoms, except the even more debilitating stomach issues, Leaky Gut, hyper-sensitivities, etc. I have tested negative for Celiac disease many times, yet, if I eat one slice of bread, my stomach will inflame and my heart rate will go into A-fib for at least 12 hours. The same if I ingest a minute amount of Citric acid, a preservative.

Does CFS still emanate from the intestines? I whole heartedly believe so.

And, to this day, I have not seen anything to prove CFS is not Lyme, or a co-factor!

oh my……………Carol………….how I can relate to everything you said… something that really hit home….”I was supposed to figure all this out on my own”. If one of my family members got really sick I would be researching my heart out. In fact as sick as I am…………..I still do that for family and friends. I’m not trying to make myself out to be a saint……but geesh. I guess everyone’s different as to how they react to a friend or loved one being ill. I love my family but havn’t really felt supported. My dad passed away before I got ill…………but if he were alive………..I know at least he would have carried me out of that bed and said……..your coming home where we can take care of you and get down to the bottom of this.

Dear Invisible,

You are courageous to put your desperate feelings into words and to share. I would surmise that many of us have had a ‘glimpse’ into your situation with your end of life thoughts (I am not able to imagine your childhood issues).

– you are allowed to feel disappointed in others, angry about the effects of ME, the lack of empathy and negative co-operation to learn and understand,

– people don’t seem to be caring about you, therefore, perhaps you could drop any expectations that others have of you and accept that others that you know may not come through for you,

– are you able to just do small things for yourself, eg: medication for pain and depression

ignore Christmas and just do things that may calm your spirit – watching the snow fall, order

cozy pajamas online.

– there is a saying that says “that depression is not a sign of weakness but a sign that one has been battling too hard for too long”.

I will pray that you find a small piece of self contentment or gratitude but I would not judge nor condemn if you had to make a final decision.

Thanks to all of you. I have had CFS for 30 years (I had, of course, to diagnose myself originally). Only once in that time did I have a doctor who took me seriously, knew anything about this illness and was of any real help. Unfortunately he was quickly suspended from seeing CFS patients because he prescribed narcotic pain meds for the worst cases. Since that time I have had no real treatment and manage on whatever my GP thinks might help or I can figure out myself (not much useful).

There is no point in me talking about all the overwhelming problems I face, frightening as they seem most days, but I very much want to say that it helps to know others are trying to cope with similar problems..and it really helps to know that this life-destroying illness is finally getting attention, even though any real solutions will probably come too late for me since I am already in my 60’s.

Hi Liz,

Yes……..doctors……sheesh. I just went to see another “pain management specialist” a few days back. I ended up having to ask to leave via the back door as I couldn’t get a grip on myself to quit crying due to his overwhelming lack of compassion and cluelessness.

The month before, when I asked if there might be anything else I could try to manage my pain, my GP of four years had told me to try a product that she thought maybe was called O-29. (It turned out she was talking about Rub A5-35.) Yes, of course that would be useful!!! Some mint liniment…….lol. I can’t put my pants on in the morning as I cannot bend at all – but mint liniment should help. Geeeeez.

Anyway…….I know we all have many many similar and worse doctor stories but your post just brought it to the forefront for me this morning.

I too feel so thankful for this blog and the chance to feel somewhat normal – as I read stories of others who are managing with even worse symptoms than I have.

Blessings to you all – bloggers and commenters.

Dawn

I was drawn to this article, because I still recall being a tot and having my Mom sit with me and read this book to me. I remember being fascinated by the steam-shovel, and laughing so hard together with my Mom when the hatchling thought that the steam-shovel was it’s mother.

Being a middle eaged single male in my early 40’s, losing my job and now entirely bankrupt financially from extensive treatment for Lyme, Babesia and Bartonella – and 4 years later still battling an extremely persistent Bartonella -but now, so violently allergic to all of the useful anti-biotics due to my over-exsposure to them. I am now in a scary place. My treatment hopes now rely on a new very well rerferenced 600 page book by Herbalist Stephen Buhner ….which even my non-integrative LLMD (in NJ) liked – but I digress.

My Mom was the best friend and caretaker I had – but we lost her 2 years ago, and it changed my life forever, and made me realize just how alone I really am. A single male, who is bankrupt with no job, surviving now soley on disability income. I had to come to terms with the fact that my hopes of meetng a companion, someone who would care and understand, and might be able to help me…. are all just desires for something that would be beyond a miracle to expect. Even though it is 2013 …regardless of what anyone says, males are still supposed to be “providers” – and I can barely take care of myself at this point, let alone anyone else. I just cannot begin to describe the loneliness and despair that I face each and every day with all of this.

My only real thought here to express to others – Is that if you have any family, or loved ones at all – please, please try accept them for who they are, and do your best to work with their quirks –no one is an angel or a saint, but at least you have somebody there some of the time? ……Unlike myself who is totally alone now, while still battling this. Short of a miracle, I have just virtually no hope of attracting someone new into my wreck of a life – it has been a complete and total disaster financially, emotionally….just on every level imaginable.

Please, please be grateful for what you do have. I thank you so much for reading this, I really just needed somewhere to vent my frustration with my own personal situation.

Ed in NJ

Blessings to you Ed.

If you were in my neighborhood, I would drop by with a herbal tea and a hug. Here’s hoping for better days for you – and for Stephen Buhner to be the miracle you summoned.