My assumption has been that the AHRQ knows what it’s doing and is doing its job well. That assumption is based on the fact that the AHRQ appears to be thriving as an institution.

The AHRQ notes in its report, however, that “divergent and conflicted opinions are common” even among experts in these reports. I have been told that at least one very divergent opinion has been privately expressed by a respected ME/CFS expert who was consulted for this report and whose suggestions were not taken. I contacted another ME/CFS researcher who felt that overly strict inclusion criteria prevented the inclusion of many potential biomarkers.

With that in mind let’s take a look at the probably the most controversial aspect of the report – the small number of studies included in the final analysis. First let’s ground ourselves in the first question the AHRQ was asked and how important it was.

Key Question 1. What methods are available to clinicians to diagnose ME/CFS and how does the use of these methods vary by patient subgroups?

Diagnosing ME/CFS – The current dogma is that an ME/CFS diagnosis is primarily based on identifying symptoms and ruling out other disorders. No laboratory tests are accepted diagnostic tools for ME/CFS. An AHRQ report stating that some lab tests could be used to diagnose ME/CFS would be big news, and that was clearly one of the hopes of the ME/CFS community. That didn’t happen.

Subgroups – Identifying subgroups was another important question. An AHRQ finding that x, y, or z laboratory tests could be used to diagnose specific types of patients would be another very valuable finding for this field. Since many studies have examined laboratory and other variables in ME/CFS, we might have expected that the AHRQ report would have something positive to say about finding subsets. They didn’t.

Getting positive answers to those questions, of course, would have required having the requisite studies making it to the final analysis, and they didn’t. The AHRQ included only four potential diagnostic biomarker studies out of possibly hundreds of possible studies in their analysis. That was a stunning loss.

Missing Studies

The loss was bigger than the report suggested. The AHRQ panel obviously needed to do a complete search in order to fully assess the state of diagnosis and treatment in Chronic Fatigue Syndrome.

Over 90% of the studies reviewed did not make it the final analysis….plus some studies were not reviewed at all.

Their search of the Ovid Medline database for 1988 to November Week 3 2013 brought up 5,902 potentially relevant articles of which 914 were selected for full-text review. Almost 6,000 citations is a lot of citations, but the panels search using the word “fatigue” was guaranteed to bring up an enormous number of citations.

As Erica Verillo has pointed out, Ovid Medline is a big database, but it’s not as big as the PubMed database. A search for Chronic Fatigue Syndrome on the PubMed database brings up 6400+ citations. Many of these would have been excluded because of their peripheral connection to ME/CFS, but they also appear to include studies that the Ovid Medline search missed (or were ignored).

Scanning the 60 plus pages of excluded and included studies in the AHRQ appendices suggested some important studies might be missing. A subsequent search for some prominent ME/CFS researchers indicated that many important studies were not just missing from the final analysis, but had apparently not been reviewed at all. They simply did not appear anywhere in the AHRQ’s analysis.

A 2010 study,for instance, examining immune functionality in viral vs non-viral subtypes that appeared to be a perfect study for examining subgroups was not reviewed. Remarkably, none of Shungu’s (NIH funded) brain lactate studies (which did use a disease control group) even made it to the point where they could have been excluded. Nor was Baraniuk’s stunning cerebral spinal fluid proteome study found anywhere in the report. Sometimes the omissions were hard to understand; one of the Light gene expression studies was included, but four others were not. (See Appendix for list.)

A Cook exercise study that seemingly did what the AHRQ wanted – compare ME/CFS and FM patients – didn’t make the first cut. Nor was the AHRQ seemingly aware of several studies showing reduced gray matter/ventricular volume by Lange. They missed Newton’s muscle pH and peripheral pulse biomarker studies. The exciting Schutzer study (another expensive NIH-funded study) showing different proteomes in the cerebral spinal fluid of ME/CFS and Lyme disease patients was nowhere to be seen.

This list is nowhere near complete – it simply covers some researchers I thought to look for. It suggests that possibly many studies that were never assessed for this report should have been.

Excluded studies

A central question is how could so many studies, many of them done by good researchers (with major NIH grants), have been excluded from the final analysis? The exclusionary criteria prevented the AHRQ from assessing dozens of possible diagnostic biomarker studies. Natural killer cells, cerebral blood flow, exercise studies, pathogen studies, hormones, etc. – many important studies – all went by the wayside. An AHRQ positive report on any physiological biomarker of them would have been helpful given the behavioral headwinds ME/CFS still has to confront. Not one made the cut.

I don’t have the expertise to determine if the AHRQ’s inclusion and exclusion criteria were too strict, not strict enough, or just right. Judging from the results, the bar for admission was a high one indeed.

The AHRQ provided a list of exclusionary factors as well as a list of excluded studies and the reason for their exclusion. I went through about half of the excluded studies – about thirty pages worth – and divided them into potential treatment and diagnostic biomarker studies. The list of excluded potential diagnostic biomarker studies stretched to ten pages!

Exclusionary Criteria

The basic exclusionary criteria are below.

| 2,3,4 | Excluded because the study does not address a Key Question or meet inclusion criteria, but full text pulled to provide background information |

| 5 | Wrong population |

| 6 | Wrong intervention |

| 7 | Wrong outcomes |

| 8 | Wrong study design for Key Question |

| 9 | Wrong publication type |

| 10 | Foreign language |

| 11 | Not a human population |

| 12 | Inadequate duration |

The AHRQ’s rigorous exclusion criteria knocked over 90% of the reviewed studies from the final analysis, but the AHRQ was vague in explaining what they were defining as exclusion criteria. Given how important the exclusion criteria ended up being, their laxity in this area was surprising.

Exclusion criteria #2, for instance, was the most commonly used reason for excluding a diagnostic study, but it’s impossible to tell what it (or reasons 3 or 4) refer to. The report simply states that exclusion criteria 2, 3, and 4 refer to studies that did not address the Key Question, meet inclusion criteria, or ???.

Similarly, exclusion criteria #9, “wrong publication type,” was the most common reason for rejecting a treatment study, but there is no explanation that I can find in the report or the appendices that explains what a “wrong publication type” is. (A search of the 300 plus pages of their “methods manual” was fruitless.)

The list above only begins, however, the list of exclusionary factors. Studies that didn’t meet the AHRQ’s “inclusion criteria” were also excluded, and among those inclusion criteria are more exclusionary factors as well.

Studies rejected because of “wrong study design”, for instance, include “non-systematic reviews, letters to the editor, before and after studies, case-control studies, non-comparative studies, reviews not in English, and studies published before 1988.”

Inclusion Criteria – for Diagnostic Studies

Then there are the inclusion criteria which are absolutely required for the inclusion of “diagnostic studies” in the analysis.

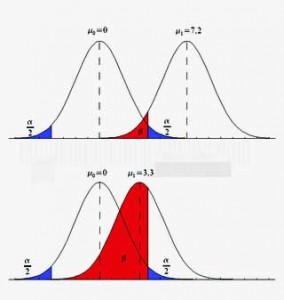

These criteria required that comparators of diagnostic accuracy and concordance be done – a process that appears to require that at least one of the following diagnostic outcome measures be assessed: sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, negative predictive value, positive likelihood ratio, negative likelihood ratio, C statistic (AUROC), net reclassification index, concordance, any potential harm from diagnosis (such as psychological harms, labeling, risk from diagnostic test, misdiagnosis, other).

Studies that did not include some of these statistical analyses were excluded from the review.

This requirement appeared to be a deal breaker for many of the putative biomarker studies. Most studies that have assessed potential biomarkers – whether NK cell functioning or cerebral blood flow – are what the AHRQ referred to as “etiological studies” looking for the cause of ME/CFS. They generally did statistical analyses that differentiated ME/CFS patients from healthy controls, but they did not do the types of analyses the AHRQ believes are needed to validate them as diagnostic tools.

The fact that many good researchers, some of whom have gotten significant grants from the NIH (indicating their study designs are solid), didn’t do these analyses suggests that these may be specialized types of analyses they’re not familiar with or don’t think are necessary.

Common Reasons for Exclusion

Now we look at a couple of the more common reasons for excluding a study from review.

Exclusion Criterion #2

Occurring in 45 of the 119 studies I pulled, exclusion criterion #2 was the most common reason cited for not including a possible diagnostic biomarker study. Since I examined about half the excluded studies, it’s possible that this one criterion was responsible for over 100 studies being excluded from the final report.

Unfortunately, it’s impossible to determine whether these studies were excluded because they didn’t address a Key Question or because they didn’t meet inclusion criteria.

Here are some examples taken randomly from potential diagnostic biomarker studies that failed based on Inclusion criterion 2:

- A recent immunological biomarker study found distinct differences between NK cells and immune factors in ME/CFS patients and healthy controls, but stopped there. None of the statistical analyses the AHRQ was looking (sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, negative predictive value, positive likelihood ratio, etc.) were done.

- A 1997 markers of inflammation study did include both chronic fatigue and chronic fatigue syndrome patients, but did none of the statistical analyses the AHRQ was looking for.

- A 2005 serotonin receptor binding study (containing all of ten patients) found differences between healthy controls and CFS patients but did no further analyses

- An oft-cited 1991 cortisol study examined the differences between healthy controls and ME/CFS patients and found them – but did no further analyses.

- A 2012 study that did indeed find impaired cardiac functioning in ME/CFS (in 10 patients and 12 healthy controls) didn’t do any of the diagnostic analyses the AHRQ was looking for.

- Kerr’s gene expression subtype study did look at a variety of clinical phenotypes but did not include any of the statistical analyses the AHRQ was looking for.

- Snell’s study that used a classification analysis to show that a two-day exercise test was 95% accurate in distinguishing between ME/CFS patients and healthy controls, despite the extra statistical analyses included, also did not meet the inclusion criteria.

Studies that Should Have Been Included?

Doing a PubMed search I found several studies that did appear to meet the AHRQ’s statistical analysis requirements. All the studies below used an ROC analysis that produced sensitivity and specificity data. Some of these studies (plasma cytokines, energy metabolism, peripheral pulse) do not appear to have been reviewed at all.

-

Plasma cytokines in women with chronic fatigue syndrome Fletcher MA1, Zeng XR, Barnes Z, Levis S, Klimas NG.

- Chronic fatigue syndrome and impaired peripheral pulse characteristics on orthostasis–a new potential diagnostic biomarker. Allen J1, Murray A, Di Maria C, Newton JL.

- Decreased expression of CD69 in chronic fatigue syndrome in relation to inflammatory markers: evidence for a severe disorder in the early activation of T lymphocytes and natural killer cells. Mihaylova I1, DeRuyter M, Rummens JL, Bosmans E, Maes M.

- Altern Ther Health Med. 2012 Jan-Feb;18(1):36-40. The assessment of the energy metabolism in patients with chronic fatigue syndrome by serum fluorescence emission. Mikirova N1, Casciari J, Hunninghake R.

Exclusionary Criterion #8

With 25 citations exclusionary criterion #8 “Wrong Study Design” was the next most commonly cited reason to exclude studies from the final analysis. Reasons for not accepting a study based on study design included “Non-systematic reviews, letters to the editor, before and after studies, case-control studies, non-comparative studies, reviews not in English, and studies published before 1988”

Using case-control designs ended up being a big factor in the randomly picked studies I pulled out.

- The use of a case-control design (a prohibited study design) appears to have doomed a study finding an increased incidence of severe life events three months prior to getting ME/CFS.

- The case-control nature of the Jammes study finding high levels of oxidative stress and HSP factors after exercise in ME/CFS appears to have eliminated it from consideration as well.

- Case-control problems popped up again in Newton’s recent study finding increased acidosis after exercise study.

- It was not clear what study design issues stopped a 1998 study finding reduced cognition after exercise from being included.

Conclusion

Stiff exclusionary criteria resulted in over 90% of ME/CFS studies not making the final cut, leaving possibly hundreds of biomarker studies out of the final analysis. A significant number of studies appear not to have been reviewed at all. Several diagnostic studies that were excluded from the analysis also appeared, at least to this layman, to fit their inclusion criteria. The AHRQ’s inability to explain several important exclusion criteria in sufficient detail made it impossible to tell exactly why many studies were excluded.

Including the missing studies might have provided more meat for the AHRQ to work with, but it’s hard to escape the conclusion that the stiff inclusion/exclusion criteria were the primary reason for the report’s paltry findings. Including studies that the panel missed or which did the ROC analyses the AHRQ appeared to be looking for might, however, have changed the complexion of the report.

Several ME/CFS experts have privately expressed concern at the AHRQ’s findings. We’re also waiting on the SolveME/CFS Association’s review of the report.

Appendix

Studies Missed (Not Included or Excluded in the Review)

J Behav Neurosci Res. 2010 Jun 1;8(2):1-8. A Comparison of Immune Functionality in Viral versus Non-Viral CFS Subtypes. Porter N1, Lerch A2, Jason LA, Sorenson M, Fletcher MA, Herrington J.

Cytokine expression profiles of immune imbalance in post-mononucleosis chronic fatigue. Broderick G, Katz BZ, Fernandes H, Fletcher MA, Klimas N, Smith FA, O’Gorman MR, Vernon SD, Taylor R. J Transl Med. 2012 Sep 13;10:191. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-10-191.

Exercise responsive genes measured in peripheral blood of women with chronic fatigue syndrome and matched control subjects. Whistler T, Jones JF, Unger ER, Vernon SD.

A Chronic Fatigue Syndrome – related proteome in human cerebrospinal fluid. Baraniuk JN, Casado B, Maibach H, Clauw DJ, Pannell LK, Hess S S. BMC Neurol. 2005 Dec 1;5:22.

Differences in metabolite-detecting, adrenergic, and immune gene expression after moderate exercise in patients with chronic fatigue syndrome, patients with multiple sclerosis, and healthy controls. White AT, Light AR, Hughen RW, Vanhaitsma TA, Light KC.

Genetics and Gene Expression Involving Stress and Distress Pathways in Fibromyalgia with and without Comorbid Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. Light KC, White AT, Tadler S, Iacob E, Light AR.

Severity of symptom flare after moderate exercise is linked to cytokine activity in chronic fatigue syndrome. White AT, Light AR, Hughen RW, Bateman L, Martins TB, Hill HR, Light KC.

Moderate exercise increases expression for sensory, adrenergic, and immune genes in chronic fatigue syndrome patients but not in normal subjects. Light AR, White AT, Hughen RW, Light KC. Psychosom Med. 2012 Jan;74(1):46-54. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31824152ed. Epub 2011 Dec 30.

Cerebral vascular control is associated with skeletal muscle pH in chronic fatigue syndromepatients both at rest and during dynamic stimulation. He J, Hollingsworth KG, Newton JL, Blamire AM.

Clinical characteristics of a novel subgroup of chronic fatigue syndrome patients with postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome. Lewis I, Pairman J, Spickett G, Newton JL.

Chronic fatigue syndrome and impaired peripheral pulse characteristics on orthostasis–a new potential diagnostic biomarker. Allen J, Murray A, Di Maria C, Newton JL.

Physiol Meas. 2012 Feb;33(2):231-41. doi: 10.1088/0967-3334/33/2/231. Epub 2012 Jan 25. Chronic fatigue syndrome and impaired peripheral pulse characteristics on orthostasis–a new potential diagnostic biomarker.

Allen J1, Murray A, Di Maria C, Newton JL. Increased d-lactic Acid intestinal bacteria in patients with chronic fatigue syndrome.

Sheedy JR, Wettenhall RE, Scanlon D, Gooley PR, Lewis DP, McGregor N, Stapleton DI, Butt HL, DE Meirleir KL. In Vivo. 2009 Jul-Aug;23(4):621-8.

Responses to exercise differ for chronic fatigue syndrome patients with fibromyalgia. Cook DB, Stegner AJ, Nagelkirk PR, Meyer JD, Togo F, Natelson BH. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2012 Jun;44(6):1186-93. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3182417b9a.

Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2005 Sep;37(9):1460-7. Exercise and cognitive performance in chronic fatigue syndrome. Cook DB1, Nagelkirk PR, Peckerman A, Poluri A, Mores J, Natelson BH.

Regional grey and white matter volumetric changes in myalgic encephalomyelitis (chronic fatigue syndrome): a voxel-based morphometry 3 T MRI study. Puri BK1, Jakeman PM, Agour M, Gunatilake KD, Fernando KA, Gurusinghe AI, Treasaden IH, Waldman AD, Gishen P.

Unravelling intracellular immune dysfunctions in chronic fatigue syndrome: interactions between protein kinase R activity, RNase L cleavage and elastase activity, and their clinical relevance. Meeus M, Nijs J, McGregor N, Meeusen R, De Schutter G, Truijen S, Frémont M, Van Hoof E, De Meirleir K. In Vivo. 2008 Jan-Feb;22(1):115-21.

Detection of herpesviruses and parvovirus B19 in gastric and intestinal mucosa of chronic fatigue syndrome patients. Frémont M, Metzger K, Rady H, Hulstaert J, De Meirleir K. In Vivo. 2009 Mar-Apr;23(2):209-13.

J Psychosom Res. 2006 Jun;60(6):559-66. Impaired natural immunity, cognitive dysfunction, and physical symptoms in patients with chronic fatigue syndrome: preliminary evidence for a subgroup? Siegel SD1, Antoni MH, Fletcher MA, Maher K, Segota MC, Klimas N.

Neuroimage. 2005 Jul 1;26(3):777-81. Epub 2005 Apr 7. Gray matter volume reduction in the chronic fatigue syndrome. de Lange FP1, Kalkman JS, Bleijenberg G, Hagoort P, van der Meer JW, Toni I.

Neuroimage. 2005 Jun;26(2):513-24. Epub 2005 Apr 7. Objective evidence of cognitive complaints in Chronic Fatigue Syndrome: a BOLD fMRI study of verbal working memory. Lange G1, Steffener J, Cook DB, Bly BM, Christodoulou C, Liu WC, Deluca J, Natelson BH. Appl Neuropsychol. 2001;8(1):23-30.

Quantitative assessment of cerebral ventricular volumes in chronic fatigue syndrome. Lange G1, Holodny AI, DeLuca J, Lee HJ, Yan XH, Steffener J, Natelson BH. PLoS One. 2011 Feb 23;6(2):e17287. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017287.

Distinct cerebrospinal fluid proteomes differentiate post-treatment lyme disease from chronic fatigue syndrome. Schutzer SE1, Angel TE, Liu T, Schepmoes AA, Clauss TR, Adkins JN, Camp DG, Holland BK, Bergquist J, Coyle PK, Smith RD, Fallon BA, Natelson BH.

Wow, Cort. Just speechless. Amazing research on your part — thank you,

Thanks! (I’m sure a lot more could be done…)

I’m glad to see that research in ME/CFS is getting more attention. While I’m not qualified to judge the studies, it does seem that many of them seem very inconclusive, and some, especially those that bandy about psychosomatic explanations, seem terrible. Yet, what I also wonder is if the rigorous statistical standards used in this meta-study might possibly be dismissing important insights which could then be taken and further developed in subsequent work that could prove valuable. It has been said that the perfect is the enemy of the good. Let’s not toss out the good.

I’m sure there’s lot’s of good insights and probably quite a few biomarkers in there..There are quite a few NIH funded studies in there – good study designs – just not what the AHRQ was looking for with regards to diagnostic biomarkers.

Can someone give it to me straight as my brain fog makes connecting dots difficult. Why does it seem that there is some conspiracy and that it looks an awful lot like there is a huge effort to stop researchers solving CFS or even legitimizing our suffering.

For someone living in a fog- I just can’t understand this. Can someone explain why there is so much working against us and what the likelyhood of uncovering the cause of CFS truly is? I’d appreciate it 🙂

I don’t believe there is one and I don’t think researchers believe there is one either. Dr. Peterson, who has been in this field for three decades, doesn’t believe there is a conspiracy either.

With regards to the AHRQ you have to ask yourself why a couple of PhD’s there who do nothing other than assess treatment efficacy, etc. for all sorts of disorders would decide to conspire amongst themselves to trash ME/CFS – possibly at the cost of losing their jobs) (Since AHRQ is supposed to be above all objective – that’s why they get clients – they would certainly lose their jobs if it was found that they treated ME/CFS unfairly.)

Why would they treat ME/CFS any differently? Why would they have strong feelings about it at all? I imagine they treated ME/CFS like they do any other disorders they analyze.

As to other areas – There is definitely a mindset at the NIH and funding organization – that ME/CFS is not worth funding… You might call a conspiracy – but I don’t see people getting together to undercut ME/CFS – I think of it more as a pervasive mindset 🙂

Thank you for all that incredible information Cort. The results of the report couldn’t be more disapointing.

I am curious to know, was the PACE study include in this report?

PACE was not only included, it was one of six studies rated “Good” quality (which has a technical meaning in the report). The Reviewers ignored (or excluded) all of the evidence calling the PACE study into question. This includes the post hoc change in the definition of recovery, the poor six minute walking test results, and on and on.

yes, it was included and rated a good-quality study (!), as was the FINE trial

That is astonishing and calls the whole process of the AHRQ report into question because as I recall the FINE trial results were deemed to be a failure at the time of their release.

I find that truly astonishing as at the time the FINE Trials results were published they were deemed to have failed. Surely that must call the AHRQ report into question. How could that happen?

Very, very impressive, thank you Cort. Reviewing all that stuff must have cost you an arm and a leg.

One wonders huh, why they missed these studies?

I have no idea why they were missed. I wasn’t able to access Medscape to see if their search brought them up. Their search could have missed them or they could have dismissed them early on – although I can’t imagine why they would.

This is actually any extremely helpful analysis. I hope it is OK to use components in my own response to the AHRQ report. I also very much hope that you are planning to submit these comments. Thanks!

I hope Cort and/or anyone who has time submits the list of studies that look like they should have been included.

I will

Kudos to you for sorting out all this mess.

Cort,

How is it that all these very experienced researchers don’t know the criteria expected of them for these studies? How do they manage to get funding if they don’t meet these strict criteria in the first place?

Your persistence and questioning of these matters is very appreciated!

Thanks so much,

Kathe

Great question. I think we should note that among the excluded studies are some big NIH funded studies that do go through a rigorous review process and do have good study designs. So they’re good studies – for determining etiology but they didn’t go far enough, the AHRQ asserts, to produce validated biomarkers.

Dr. Klimas’ group appears to be ahead of the curve in this area; they had several studies that ROC analyses but which still got excluded – why, I don’t know.

I can only conclude these are statistical analyses that many researchers aren’t familiar with. Hopefully they will be now.

I think the IACFS/ME should do summarize this report and post a page on their website and send a message to their members stating – if you think you have a biomarker – do these analyses! Think how many potential biomarkers there are out that could make a big difference to the ME/CFS field – if the right analyses had been done….

Great idea! The psychologists clearly know the standards by which their research will be judged. They are generally highly trained in experimental design and statistical analysis, that’s why so many of their studies were included. Having our researchers conform to the stated standards will enable us all to get the most out of the work they are doing.

Thank you for working through this report for us, Cort. It’s clear that you’ve put a tremendous amount of work into it. I’m so glad we have your experienced and educated perspective.

ME/CFS is a never ending story…. 🙁

It’s one thing or another isn’t it? 🙂

Cort, awesome “reading between and in the lines” here. I’d have to read this article innumerable times to feel that I’ve even gotten the gist. However, I do have a question: is this the Institute of Open Medicine’s findings? I suppose in science coincidence does not determine causality which is why so many MD’s are hesitant to do testing when they have no follow-up protocol for the results. But….if bring to mind my brother who has Multiple Sclerosis, I must assume that sufficient repeated research was done to determine that the ONLY disease in which lesions form in the brain is MS…. hence bringing back the need for (GROAN!) further research re: many of the current findings to ascertain if they are unique to CFS/ME or simply a symptom of several disorders. So back to the drawing board with hopes that the NIH and CDC will continue funding further research to determine that which is unique to our/my illness? In a nutshell, is this what this article says?

What occurs to me is the question of how many studies concerning all the other illnesses and conditions including psychiatric ones, from this point in time back to the beginning of modern science, would pass their set of criteria? Almost none, I would expect. Probably most of what has been established and built upon as “true” or generally valid at least, would have been swept aside.

No one at the outset announced that valid studies all had to fulfill those criteria. If this had been the case precious little research could have been done, as it would have been so expensive for one thing, and also because what they were seeking to understand had too many unknowns as yet to have all that solid ground of established fact to work with.

Imagine these days if the drug companies studies which supposedly establish the efficacy and safety of their drugs were judged by these strict standards? Many of us have heard of all the politics and slight of hand which go into the “proofs” that these drugs are efficacious and safe. For instance, all the studies which contradict what the drug companies want the scientific community and public to believe may be suppressed and only the ones with the outcome they wish for, at sometimes the slightest possible degree of statistical significance, will be published.

So…..if our condition has to meet the standards for validity which this organization holds to, the highest ones that can perhaps be stated, even though masses of other research which has been accepted for other conditions has not met these particular criteria for validity, and even though our researchers are not funded and supported so that they can conduct these kinds of studies, and even though a multi-systemic illnesses with so many different “moving parts” cannot provide the required number of constants against which to test only a single variable…..

How foolish is that?

Oh yes, and thank you, Cort, for working through so much of that material for us. I do feel we need to try to take the bull by the horns, through our best understanding, in order to turn it around.

Medscape just published a 4 page article on this topic here: http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/833428#vp_4

Among it’s many interesting points is that the reason so many studies were excluded really boils down to lack of funding, large studies and extensive statistical analysis take large amounts of money to complete. The researchers said that the NIH should be ashamed of themselves for forcing the private sector to step in and pay for research that they should be funding. The NIH said that the amount of money allocated to a topic is a function of how many researchers are interested in and applying for funds to study that topic as well as the caliber of the researchers applying.

At least the whole topic of ME/CFS is being written about and discussed in a source of medical news popular with physicians.

Well said, fellow Medscaper.

This is all fascinating news, Cort. Thank you. And I’d really like to read the Medscape article, but I’m not a member of the site. Could someone make it available to us, please?

Membership is free. Just sign up.

Here’s the comment I sent in:

Frequent Use of Oxford Definition May Skew Results of CBT and GET Trials

Eight of the 13 CBT/GET studies that I was able determine the definition used patients used the Oxford definition to select the patients in their study. One study I unable to assess the definition used came from a research group which had used Oxford definition in three other studies. That suggests that it’s likely that 9/14 studies or 65% of the studies the AHRQ relied upon to determine the effectiveness of CBT/GET used a definition the AHRQ report warned was suspect.

The Oxford definition – created in the UK – has been consistently used to my knowledge by behavioral researchers in the UK to assess the efficacy of CBT and GET in ME/CFS. The fact that no US or researchers from other countries have used this definition demonstrates the lack of confidence most ME/CFS researchers have in the definition. Because the definition requires only a short duration of fatigue and no other symptoms it probably greatly increases the heterogeneity of “Chronic Fatigue Syndrome” patients used in its studies.

Given the AHRQ’s warning regarding the Oxford Definition ““This (the Oxford definition) has the potential of inappropriately including patients that would not otherwise be diagnosed with ME/CFS and may provide misleading results.”, the frequent use of Oxford definition in CBT/GET trials should be noted in the report. Given the predominance of the use of the Oxford definition in CBT/GET trials, the Panel should consider reducing the level of their confidence in the CBT/GET findings from “moderate” to “low”.

The AHRQ reviewers might also note that government support for behavioral research in the UK and Europe has resulted in a plethora of large clinical trials using these approaches. These much larger trials – many with hundreds and some with over 500 patients – have enabled researchers to tease out effects that are not able to be distinguished in the much smaller drug or alternative health treatment trials. Not only do CBT/GET trials tend to be much larger than other treatment trials they are much more frequently done: compare the 18 CBT/GET trials in the final report vs only two drug triasl (that I was able to find) that was repeated more than once (Ampligen, citalopram) either in the included or excluded studies.

(The excluded studies contain 26 more CBT/GET studies for total of over 40 attempts to validate these therapies… )

Until drug and treatment types of trials receive similar levels of financial support as have behavioral treatments it will be impossible to determine their effectiveness relative to behavioral approaches.

Missing Studies

Scanning the 60 plus pages of excluded and included studies in the AHRQ appendices suggested some important studies might be missing. A subsequent search for some prominent ME/CFS researchers indicated that many important studies were not just missing from the final analysis, but had apparently not been reviewed at all. They simply did not appear anywhere in the AHRQ’s analysis.

A 2010 study,for instance, examining immune functionality in viral vs non-viral subtypes that appeared to be a perfect study for examining subgroups was not reviewed. Remarkably, none of Shungu’s (NIH funded) brain lactate studies (which did use a disease control group) even made it to the point where they could have been excluded. Nor was Baraniuk’s stunning cerebral spinal fluid proteome study found anywhere in the report. Sometimes the omissions were hard to understand; one of the Light gene expression studies was included, but four others were not.

The ability to quickly find over twenty missing studies –including NIH and Center’s for Disease Control funded studies done by well-known researchers in the field – suggested the AHRQ panel ‘s search was incomplete and many other studies may have been missed. (See end of document for missing studies).

AHRQ’s Vague Exclusion Criteria Hampers Understanding of Report

The purpose of the P2P report is outline gaps in research regarding defining, diagnosing and treating Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. Ironically, several of the P2P exclusionary criteria were so vague as to defeat understanding of how they were used.

The AHRQ’s rigorous exclusion criteria knocked over 90% of the reviewed studies from the final analysis, but the AHRQ was vague in explaining what they were defining as exclusion criteria. Given how important the exclusion criteria ended up being, their laxity in this area was surprising.

Exclusion criteria #2, for instance, was the most commonly used reason for excluding a diagnostic study, but it’s impossible to tell what it (or reasons 3 or 4) refer to. The report simply states that exclusion criteria 2, 3, and 4 refer to studies that did not address the Key Question, meet inclusion criteria, or ???. Some vague exclusion criteria made it difficult to analyse the analysis

Similarly, exclusion criteria #9, “wrong publication type,” was the most common reason for rejecting a treatment study, but there is no explanation that I can find in the report or the appendices that explains what a “wrong publication type” is.

AHRQ Report Reflects Poor Federal Support for Chronic Fatigue Syndrome

Despite the fact that Chronic Fatigue Syndrome affects from 1-3 million people in the U.S., causes up to 20 billion dollars a year in economic losses and has rates of disability similar to those found in multiple sclerosis it is amongst the poorest funded disorders at the NIH.

One must ask how could a complex disorder like ME/CFS be in good shape on a $5 million/year budget at the NIH? The NIH is funding ME/CFS at a lower rate adjusted for inflation than it did twenty years ago. How could ME/CFS treatment be in good shape with just one drug in thirty years making it though the FDA – only to fail? How could the field not fail to meet standards of scientific rigor with a variety of definitions vying for prominence? The field is so unformed that some researchers (Wyller in Norway) feel comfortable creating their own definitions.

To say almost 30 years later that you cannot say anything firm about the effectiveness of treatments is a damning indictment of the medical research establishment’s support of the Chronic Fatigue Syndrome community. To have only 39 treatment trials qualify for inclusion in this report – most of which were of poor to fair quality – from almost 30 years of study is astonishing. To have only one drug or alternative treatment provide other than “insufficient” evidence of it’s effectiveness in ME/CFS is tragic in a disorder effecting a million people in the U.S. and millions more across the world.

Read between the lines and this report says that ME/CFS has been spectacularly poorly studied, that it lacks fundamental tools that other disorders have, and until it has those tools not much effective work is going to be done in the realm of diagnosis and treatment.

More than anything this report reflects the unwillingness of the NIH to even begin to grapple with the issues facing the ME/CFS field. The last (small) NIH RFA for ME/CFS was in 2003. Despite a paucity of informed physicians the NIH has repeatedly refused to fund Centers of Excellence. Since the closure of three federally funded research centers in 2001 and the move to Office of the Director, funding has been on long road of decline. Despite the many people affected ME/CFS is in the bottom five percent of disorders and conditions funded by the NIH.

The AHRQ report simply highlights the tragic consequences that three decades of federal neglect have had for at least a million chronically ill and often disabled Americans who have no validated treatments and few doctors to turn to.

Studies not Found in Either the Included or Excluded Study Sections

A Comparison of Immune Functionality in Viral versus Non-Viral CFS Subtypes.

Porter N1, Lerch A2, Jason LA, Sorenson M, Fletcher MA, Herrington J.

Cytokine expression profiles of immune imbalance in post-mononucleosis chronic fatigue. Broderick G, Katz BZ, Fernandes H, Fletcher MA, Klimas N, Smith FA, O’Gorman MR, Vernon SD, Taylor R. J Transl Med. 2012 Sep 13;10:191. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-10-191.

Exercise responsive genes measured in peripheral blood of women with chronic fatigue syndrome and matched control subjects.

Whistler T, Jones JF, Unger ER, Vernon SD.

A Chronic Fatigue Syndrome – related proteome in human cerebrospinal fluid.

Baraniuk JN, Casado B, Maibach H, Clauw DJ, Pannell LK, Hess S S.

BMC Neurol. 2005 Dec 1;5:22.

Differences in metabolite-detecting, adrenergic, and immune gene expression after moderate exercise in patients with chronic fatigue syndrome, patients with multiple sclerosis, and healthy controls.

White AT, Light AR, Hughen RW, Vanhaitsma TA, Light KC.

Genetics and Gene Expression Involving Stress and Distress Pathways in Fibromyalgia with and without Comorbid Chronic Fatigue Syndrome.

Light KC, White AT, Tadler S, Iacob E, Light AR.

Severity of symptom flare after moderate exercise is linked to cytokine activity in chronic fatiguesyndrome.

White AT, Light AR, Hughen RW, Bateman L, Martins TB, Hill HR, Light KC.

Moderate exercise increases expression for sensory, adrenergic, and immune genes in chronicfatigue syndrome patients but not in normal subjects.

Light AR, White AT, Hughen RW, Light KC. Psychosom Med. 2012 Jan;74(1):46-54. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31824152ed. Epub 2011 Dec 30.

Cerebral vascular control is associated with skeletal muscle pH in chronic fatigue syndromepatients both at rest and during dynamic stimulation.

He J, Hollingsworth KG, Newton JL, Blamire AM.

Clinical characteristics of a novel subgroup of chronic fatigue syndrome patients with postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome.

Lewis I, Pairman J, Spickett G, Newton JL.

Chronic fatigue syndrome and impaired peripheral pulse characteristics on orthostasis–a new potential diagnostic biomarker.

Allen J, Murray A, Di Maria C, Newton JL.

Physiol Meas. 2012 Feb;33(2):231-41. doi: 10.1088/0967-3334/33/2/231. Epub 2012 Jan 25.

Chronic fatigue syndrome and impaired peripheral pulse characteristics on orthostasis–a new potential diagnostic biomarker.

Allen J1, Murray A, Di Maria C, Newton JL.

Newton JL, Sheth A, Shin J, et al. Lower ambulatory blood pressure in chronic fatigue syndrome. Psychosom Med. 2009;71(3):361-5. PMID: 19297309. Exclusion code: 12

Increased d-lactic Acid intestinal bacteria in patients with chronic fatigue syndrome.

Sheedy JR, Wettenhall RE, Scanlon D, Gooley PR, Lewis DP, McGregor N, Stapleton DI, Butt HL, DE Meirleir KL.

In Vivo. 2009 Jul-Aug;23(4):621-8.

Responses to exercise differ for chronic fatigue syndrome patients with fibromyalgia.

Cook DB, Stegner AJ, Nagelkirk PR, Meyer JD, Togo F, Natelson BH.

Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2012 Jun;44(6):1186-93. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3182417b9a.

Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2005 Sep;37(9):1460-7.

Exercise and cognitive performance in chronic fatigue syndrome.

Cook DB1, Nagelkirk PR, Peckerman A, Poluri A, Mores J, Natelson BH.

Br J Radiol. 2012 Jul;85(1015):e270-3. doi: 10.1259/bjr/93889091. Epub 2011 Nov 29.

Regional grey and white matter volumetric changes in myalgic encephalomyelitis (chronic fatigue syndrome): a voxel-based morphometry 3 T MRI study.

Puri BK1, Jakeman PM, Agour M, Gunatilake KD, Fernando KA, Gurusinghe AI, Treasaden IH, Waldman AD, Gishen P.

Unravelling intracellular immune dysfunctions in chronic fatigue syndrome: interactions between protein kinase R activity, RNase L cleavage and elastase activity, and their clinical relevance.

Meeus M, Nijs J, McGregor N, Meeusen R, De Schutter G, Truijen S, Frémont M, Van Hoof E, De Meirleir K.

In Vivo. 2008 Jan-Feb;22(1):115-21.

Detection of herpesviruses and parvovirus B19 in gastric and intestinal mucosa of chronic fatigue syndrome patients.

Frémont M, Metzger K, Rady H, Hulstaert J, De Meirleir K.

In Vivo. 2009 Mar-Apr;23(2):209-13.

J Psychosom Res. 2006 Jun;60(6):559-66.

Impaired natural immunity, cognitive dysfunction, and physical symptoms in patients with chronic fatigue syndrome: preliminary evidence for a subgroup?

Siegel SD1, Antoni MH, Fletcher MA, Maher K, Segota MC, Klimas N.

Biomarkers for chronic fatigue.

Klimas NG, Broderick G, Fletcher MA.

Brain Behav Immun. 2012 Nov;26(8):1202-10. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2012.06.006. Epub 2012 Jun 23. Review.

Neuroimage. 2005 Jul 1;26(3):777-81. Epub 2005 Apr 7.

Gray matter volume reduction in the chronic fatigue syndrome.

de Lange FP1, Kalkman JS, Bleijenberg G, Hagoort P, van der Meer JW, Toni I.

Neuroimage. 2005 Jun;26(2):513-24. Epub 2005 Apr 7.

Objective evidence of cognitive complaints in Chronic Fatigue Syndrome: a BOLD fMRI study of verbal working memory.

Lange G1, Steffener J, Cook DB, Bly BM, Christodoulou C, Liu WC, Deluca J, Natelson BH.

Appl Neuropsychol. 2001;8(1):23-30.

Quantitative assessment of cerebral ventricular volumes in chronic fatigue syndrome.

Lange G1, Holodny AI, DeLuca J, Lee HJ, Yan XH, Steffener J, Natelson BH.

Go Cort!

It is the same old cover up. Focused seems principally on genetic biomarkers. If this study were honest and pure they would have supplied list of studies reviewed and a rationale why excluded. The absence of any such list of rationale, when we know 90%+ of expert studies

have been excluded, leaves me with little faith and honesty to the merit of this study. Indeed,

I am extremely alarmed by the degree at which CFS/ME is deliberately being kept under wraps.

1. Why because even a lay person reading the huge range of scientific finding out there (900+)

know there are several differentials of patients and they can be categorised using bio chemistry and patient history. For some suffers the causation of their conditions are a combination of environmental factors, The legal responsible for creating these environments i believe lies behind deliberately controlled and hood winked exclusion studies.

2. No one doubt studies must have controls, however the controls outlined above far outweigh the expenditure awarded these very serious and damaging conditions.

The AHRQ report is a professional embarrassment in its intention. An intention that quiet frankly only affirms the driven cover up of a very serious and torturous condition in which suffers are being openly deigned their human rights!

The AHRO report could of and should have made directives for investment to enable some of the very important studies which have been conducted to be expounded upon or recreated under acceptable ranges. To ignore or dismiss 90% is a insult on not only the hard working specialists whom have dedicated their time to helping suffers without any outward support and leaving suffers living and dying with correct support.

I have zero faith in the conduct of AHRQ actions and rationale or should i say lack of …….

Actually they provided about 60 pages of excluded studies and gave a reason for each – although admittedly their reasons were pretty vague at times.

I think the lay person comment is quite apt. A lay person would conclude that validated biomarkers were present. A reviewer steeped in assessing diagnostic protocols, on the other hand, might conclude they hadn’t done the statistics necessary to really validate them. That’s what appears to have happened here.

Instead of a coverup maybe this is just a very rigorous perusal of the science – done using standardized criteria???

The AHRQ did make some recommendations. Hopefully the P2P report will make some more including major grants for studies to create a validated definition and diagnostic biomarkers.

op’s sorry cognitive malfunction i do of course mean ‘leaving suffers WITHOUT correct support …

Where is the acknowledgement these conditions are progressive and can lead to fatality. The symptoms effect a wide range of very serious physical conditions, such as brain damage, nerve damage, endocrine damage, fibro damage, heart and renal failures. renal fatigue. vascular immunology damage, i do not include them all, so much to say, it is criminal negligence suffers are not monitored or maintained medically as their condition progresses.

Were any ME/CFS expert specialists on the panel conducting this so called review. if yes who were they and what field of expertise do they pertain to?.

As you can see i am very angry by this white wash

Yes and for good reason, but I think you may be angry at the wrong people. This study wasn’t supposed to document fatalities or how serious the disease is. It was pretty focused on how to diagnose it and how to treat it…

This is not to let federal funders off the hook for basically ignoring this disease.