Dr. Derya Unutmaz is one of those researchers we want in the ME/CFS field; he’s well-published, he’s an ace in immune system functioning, he has his own laboratory, and he’s doing cutting edge work. Suzanne Vernon described meeting in San Francisco with Esther Dyson, a technology analyst and “angel investor” who is particularly interested in healthcare solutions. [Esther Dyson is the daughter of eclectic physicist and visionary Freeman Dyson, who was the subject of the book “The Starship and the Canoe“.]

Esther Dyson suggested gettng in touch with Unutmaz. Upon doing so Dr. Unutmaz said heck yes, he’s interested in checking out Chronic Fatigue Syndrome – and now, armed with 50 samples from the SolveME/CFS Biobank, we have a new investigator in the field looking at people with Chronic Fatigue Syndrome using some of the hottest technology going.

That’s good news….

The Good, the Bad and the Ugly of the Immune System

Dr. Unutmaz spent the first part of the Solve ME/CFS Initiative’s webinar going over the good, the bad, and the ugly of the immune system functioning.

The good side of the immune system protects us against bacteria, viruses, fungi, and pathogens and helps maintain the beneficial microflora (the microbiome) in our bodies. The bad occurs when autoimmune processes attack the body, and the “ugly” occurs when inflammation runs amok in the immune system’s zeal to clear the invaders (the “destroy the village in order to save it” approach).

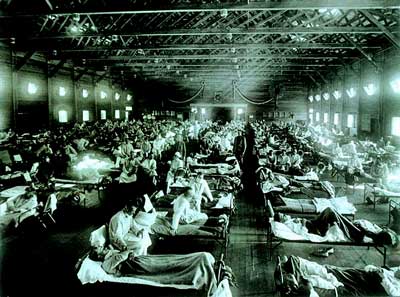

Unumatz touched on the mighty Spanish Flu that wreaked havoc during World War I. Killing some 15 million people, the Spanish Flu is a good example of an immune response that did more harm than good. Studies of the victims found that their lungs had essentially been fried – not by the flu bug, but by the ferocious immune response to the bug. In an interesting twist, it was not the elderly or sickly who were hit hardest – it was the young people with their robust immune responses who died in the greatest numbers.

[Dr. Unutmaz didn’t mention it, but later research indicated the victims had probably been exposed to a type of flu bug their systems had never seen before. The immune systems of people who had been exposed to a somewhat similar flu virus didn’t over-react – and they mostly survived.]Inflammation

Every time you have an infection the body’s immune response leaps in to clear it. Once the invader is subdued, the immune system sends out a signal to repair the damage caused. If that restorative immune response doesn’t occur because the immune system has become dysregulated, or because an infection persists, you have a state of chronic inflammation.

While it’s clear that some people with ME/CFS have high levels of inflammation, studies suggest that most people have more mildly elevated inflammation. Research indicates that inflammation is inflammation, though, and even lower levels of inflammation can have quite negative effects over time.

These lower levels of inflammation didn’t used to be taken seriously, but in the past ten years they have been. Called the “silent killer”, low levels of inflammation are associated with almost all the major killers in the western world including heart disease, cancer, diabetes, and respiratory illnesses.

Unutmaz’s hypothesis puts Chronic Fatigue Syndrome in the same company as these major disorders; he proposes that chronic inflammation is responsible for most of the symptoms of ME/CFS.

Decoding the Immune Response

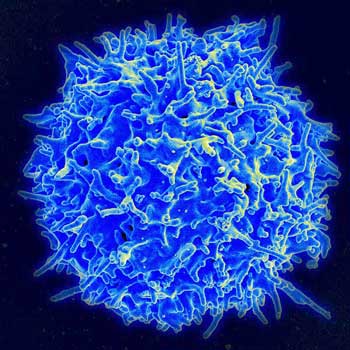

Unumatz is a T-cell expert, and his attempt to “decode” the immune response in ME/CFS begins with the T-cells that maintain the balance between inflammation and autoimmunity effector T-cells and normal immune functioning effector T-cells.

When your T-cells, mulling about in their “naïve” unactivated states, encounter evidence that a pathogen is present they become activated and differentiate into different types of T-cells.

T-cell Types

- T regulatory cells – suppress or calm down the immune response once a pathogen has been wiped out.

- TfH cells – enhance B-cell activity and contribute to autoimmunity.

- Th1 cells – fight off bacteria and viruses and contribute to autoimmunity.

- Th2 cells – fight off parasites and contribute to allergies and asthma.

- Th17 cells –fight off bacteria and fungi and contribute to autoimmunity and inflammation.

Once your immune system has fought off an infection, your cytotoxic (pathogen killing) T-cells die off leaving behind two types of T memory cells that will allow you to rapidly mount an immune response if the pathogen appears again. One type moves into lymph nodes while the other heads out to the front lines – such as the skin or any mucous membranes (mouth, gut, etc.) – where invaders are most likely to strike.

The gut with its hundred trillion (yes, that’s trillion) or so bacteria is kind of an immune nightmare waiting to happen. A couple million or so bacteria making their way out of the gut into the blood stream will put a severe strain on the immune system.

First the immune system has to get rid of them. Location is everything; these bacteria may be helpful in the gut but good gut bacteria become bad bacteria when they exit the gut. Fighting off all these different kinds of bacteria–without developing an autoimmune process that attacks our own tissues as well – is apparently not an easy task.

Dr. Unutmaz on Decoding the Immune Response

Chronic gut bacteria leakage out of the gut also increases our chances of developing a state of chronic systemic inflammation that could, Unumatz warned, lead to something like a heart attack (!).

The Big Gun

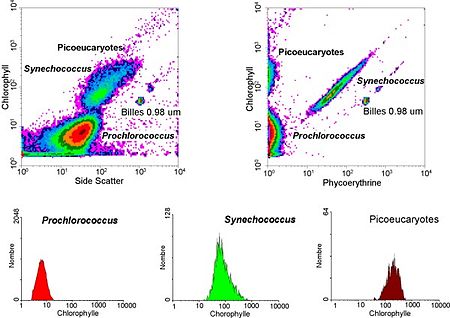

Unutmaz’s flow cytometer will not only allow him to precisely determine what kind of immune cell populations are present but what they’re doing.

Inflammation could, then, be an important factor in the development and persistence of ME/CFS. How does Unumatz propose to determine how important a factor it is?

He’s using a flow cytometer, a laser-guided machine that allows him to fluorescently label and then pick out individual cells like specific antibodies or types of B- or T-cells. Unumatz can use his flow cytometer to determine about 200 different kinds of immune cell subpopulations. He can also isolate immune cells, trigger their activation, and see what kinds of cytokines they’re making.

Personalized Medicine

“It is more important to know what kind of a person has a disease than to know what kind of a disease a person has.” – Hippocrates

While people may have the same disease, their pathways to getting the disease–may be different. This makes perfect sense when we look at the extraordinarily different responses to neuropathic pain treatments. Doctors have at least ten options for treating neuropathic pain. Some work for some people and others don’t work at all and no one, at this point, knows what, if anything, is going to work for anyone.

That’s because there are a lot of pathways to producing neuropathic pain. To be really effective, Unumatz believes medical practitioners are going to have to treat individuals, not disorders, and that’s his ultimate focus.

Unutmaz will attempt to discern unique immune pathways that distinguish ME/CFS from other disorders.

Look at any scatterplot of findings in a group of ME/CFS patients and you’ll typically see a large range of results. Even if the ME/CFS group as a whole has higher readings than another group you’ll probably still find people with lower or low normal readings. Something else is clearly going on in these people but medicine in its zeal to find treatments that fit the “average patient” mostly pretends like they are not there.

Uncovering the Immune Landscape’s Underlying Disease

That’s going to take a lot of data, but that obtaining lots of immune data and finding the different signatures present in it what Unumatz is all about. Unumatz described creating algorithms and using them to do complex bioinformatics analyses on hundreds of different immune parameters to build “immunological landscapes”.

That data includes immune profiling, functional assays that will determine how the innate (early) and adaptive (late) immune systems are functioning, plus the different genomic factors (genes, genomics, epigenetics) that affect how our immune system responds in real time.

Unumatz has collected immune information on over a thousand patients with all sorts of disorders (including the fifty ME/CFS patients). Then he’s used a “systems biology approach” to understand at a detailed level how chronic inflammation translates into different disorders. He’s attempting to find an answer to a big question: what tips an underlying inflammatory state into chronic fatigue syndrome, or a cardiovascular disease, or diabetes, or cancer?

“This research project is so incredibly important because it enables us to understand what ME/CFS is and compared to what.”– Suzanne Vernon, Research Director, Solve ME/CFS

We’ll see how the heterogeneity in ME/CFS will come into play, but if it’s successful, this work could define a unique or more likely a series of unique immune ME/CFS signatures that define the subgroups in this disorder. This is about producing biomarkers on a very detailed immune level.

Unumatz is finishing up his work with the ME/CFS groups immune data. He hopes to generate good enough pilot data from the fifty ME/CFS patients to apply for a major NIH grant.

Unumatz’s approach appears to take care of the concerns, recently stated in the AHRQ report, that ME/CFS diagnostic biomarker studies are not testing their results against people with similar disorders and similar symptoms. Unumatz will probably be testing the ME/CFS results against every prominent inflammatory disorder known.

Unumatz’s goal is to eventually be able to produce diagnostics that can zero in on solutions on an individual basis. These solutions will, he believes, include ways to reprogram the immune system so that drugs are no longer needed. [This smacks of Broderick’s work to find tipping points in ME/CFS that he can use to push the system back into a state of healthy homeostasis.]

New Digs

“JAX Genomic Medicine will discover the precise genomic causes of disease [and] develop individualized diagnostics, treatments and cures.”

Talk about “build it and they will come,” the laboratory boasts that “within 10 years, it will house 300 biomedical researchers, technicians, and support staff in state-of-the-art computing facilities and laboratories.” It’s all about developing genomic techniques that will lead to the development of personalized medicine.

Note that we’re way beyond just genetics at this point; this is genomics – a field that looks at the genes you were born with (genetics), the things that happened to you that affected those genetics (epigenomics), and your gene expression now.

The Solve ME/CFS BioBank

You can begin with this project to see just how really effective a BioBank like the Solve ME/CFS BioBank can be. Suzanne Vernon noted that the genomic data from Patrick McGowan’s epigenomics project stored in the Solve ME/CFS BioBank excited Dr. Unumatz and contributed to his taking on this project.

Protecting the Gut – The gut with its potentially huge impact on immune functioning, and, in particular, inflammation, is gathering more and more attention. Calling the gut a “very exciting area.” Unumatz noted that everyone ends up having a different flora which has been impacted by that individual’s diet, by antibiotic use, by the pathogens we’ve come into contact with, etc., but he could not provide practical solutions.

Unumatz noted that researchers are still learning the impact the gut flora has on the body. The big problem for many people with HIV, for instance, is not the virus – it’s mostly gone – but the inflammation left over from when the virus was active. They believe that inflammation sparked by HIV caused gut damage that resulted in bacterial leakage outside of the gut. The damaged gut may be feeding the inflammation that’s now present in HIV-AIDS patients.

Unumatz couldn’t give prescriptions for repairing the gut, but he could provide some personal evidence of the effects diet can have on immune functioning. He’s obviously healthy enough, but even this healthy-enough guy has found, by looking at his own immune functioning regularly, that changing his diet has definitely affected his immune functioning. One wonders what more effects it may have on the chronically ill.

Could it be that MTHFR is one of the bio-markers? I am finding a lot of people who have this genetic mutation who have fibromyalgia and chronic fatigue. Here is a link.

Methylation Problems Lead to Hundreds of Diseases | Suzy Cohen, RPh

http://suzycohen.com/project/567/

Patty Butts

http://irecoverdfromchronicfatigueandfibro.blogspot.com/

Very interested to see how this chronic inflammation relates to cancer and respiratory disease… The MTHFR genetic mutation Patty refers to is another interesting piece of the puzzle as I’ve recently discovered I too have this genetic mutation and have recently changed the forms of B-12 and Folic Acid I’ve been taking and have noticed a difference in a relatively short period of time.

Glad to have Dr. Unutmaz working to help unravel the ME/CFS puzzle!

This is a busy guy! It’s gratifying that he’s interested in and sees ME/CFS as an inflammatory disorder and that he’s willing to do a webinar on it.

BRAVO! Well done blog.

Coming back around to what I’ve been saying, Autoimmune system malfunction and inflammation. AND the one thing we can do about it DIET.

Issie

It was REALLY intriguing to hear Unutmaz say that changing his diet clearly effected how well his immune system was functioning!

I would like to see some research in red bloodcels.

What if there are no specific immune problems in ME, it looks like this is the case.

Gijs,

Based only on my personal experience, I can’t agree with your supposition that “there are no specific immune problems in ME”. Prior to the respiratory infection that caused my acute onset of alarming symptoms (diagnosed as severe ME 1 1/2 years later), I experienced one “super cold”, and at least one outbreak of cold sores every year. Otherwise, I was healthy, with no functional limitations, despite an extremely demanding lifestyle. In contrast, during the 25+ years since developing ME, I have had only three mild colds (most recently 9 1/2 years ago), no flu whatsoever, and one outbreak of cold sores.

No doubt, many would interpret this as my being protected by a supremely effective immune system. However, I would gladly trade my daily cognitive and physical limitations for the short-term discomfort of an occasional cold or flu. That way, I could at least live a “normal” lifestyle for the remaining 50 weeks of the year.

I am aware that some ME patients get every “bug” that’s going around. But, I could probably sit in a room of sick people with everyone coughing on me and not “catch'” what they have. So, perhaps these contrasting experiences are evidence of the ME “subsets” being talked about on this blog. Some of us have overactive immune systems, some underactive — both signs of immune problems, it seems to me.

Karen

I have read that when the IFN antiviral response ramps up during an infection it’s really hard to catch something else. I don’t know if it can last for 25 years – maybe it can – I have no idea. Something lasts for decades in this disorder.

Some of us have overactive immune systems, some underactive. I agee on this Karen but how can we meassure this objectively? We can’t at this point. I think that overactivity is the most common one. The ANS is the key driver i think.

Some of us have both overactive and under active immune systems at the same time. I have Hypogammagobulinemia, which is low IGG levels and almost zero immunity to the 26 kinds of pneumonia I was tested for. At the same time I have over reaction of my immune system with at least two illnesses – vitiligo and allopecia. One of the most recent things I’ve read is the bodies immune system having issues in breaking down proteins. The article I was reading suggested that when we ingest animal proteins, sometimes the body gets confused and attacks our own proteins. That would be our body. Plant proteins are different and the body can distinguish the difference. One thing known in MS is dairy can trigger a flare. A good bit of our immune system is in our gut and it would make sense we would support it there. DIET is a key here.

If our immune system were working properly we would not have issues with bacteria, virus and protozoa. Our bodies would recognize these things as foreign and attack properly.

Inflammation is probably an affect of a faulty immune system. Is the ANS messed up? Most definitely. But it could be a compensatory response.

Just my opinion.

Issie

We’ll have to see how it turns out. With his ability to characterize some 200 subpopulations of immune cells he is digging so deeply into the immune system that if something is there I imagine he will find it (that is if he is doing the complete analysis on ME/CFS patients – he may not be in this pilot study.)

My guess is that he will uncover a couple of unique immune signatures…The still unpublished Stanford gene expression study really pointed at inflammation as key driver in ME/CFS…

Thanks cort. I am still not sure if the immunesystem is the key driver. Don”t forget the ANS overdrive 🙂

Hey, I’m an ANS guy – I think it has to play a major role but it does play a major role in immune functioning. Van Elzakker cleverly tied infection, the immune system and the ANS together with his vagus nerve theory. A pooped out vagus nerve could result in SNS overdrive.

I think Van Elzakker is looking on the right spot 🙂 But also the gut is interesting!

I hope this isn’t too off-topic but i wonder if this chronic state also prevents the healing of other things- i have a long standing injury, nothing serious, that just won’t heal. I bet if i didn’t have CFS, it would’ve healed by now.

I have a question (off-topic) for anyone who knows the answer:

Is there any disease known which causes a sympathetic overdrive?

Cause and effect or response in some cases. If an overactive sympathetic system kicks into action – what is the cause. Is it compensatory and very necessary for life. If it is compensatory, and we block its action with meds, what’s the effect? Not good. If it’s poor circulation and problems with getting blood to the heart and head, the sympathetic system kicks in to cause the heart to increase beating to try to move blood to the vital areas. If there is inadequate pumping from the limbs it’s up to the heart to do this. Lots of ideas as to why the dysfunction of the blood flow. One thing being found is protazoa that lives in biofilm causing blockages and inability of the vessels to expand and contract properly. I have HyperPOTS which causes severe overreaction of the sympathetic system. I have high NE levels with standing and tachycardia not only with standing but sitting still too. Since finding this protazoa and a coinfection connected to Lyme and working on breaking down biofilm and therefore the protazoa, bacteria and virus that live in them – I’m so much better. This approach works on the immune system. So maybe not a disease to cause this. But there could be a good cause. And then we have cause and effect/response.

Issie

I’m just like Karen (above comment), I could sit in a room of full of sick people and not get sick. I might initially react to the germs surrounding me by coughing or sneezing, but once I leave the room, my reaction to the germs/virus also subsides. The invader doesn’t get passed the front door (my mouth and nose). I will not become infected, and I will not get sick.

Just because you appear to be young and healthy doesn’t mean you have a strong immune system. Some of the healthiest “looking” people succumb to diseases like cancer, HIV/AIDS, diabetes and viruses because they were not born with robust immunity. That, so many young men died during World War I from the Spanish flu had more to do with the circumstances of the time. The war contributed greatly to the seriousness of the 1918 flu. Food shortages and crowded, dirty conditions were a major factor in the spread of the disease. It was a time in which doctors lacked intensive care units, respirators, antiviral agents and antibiotics. Most deaths in the 1918 influenza pandemic were due not to the virus alone but to common bacterial infections that caused secondary pneumonia

I don’t buy into this theory, that the healthiest people were in the greatest danger from the 1918 flu because of an overreaction to the virus. A quick-acting, innately strong immune system will take care of an invading flu virus. It’s people with weakened immune systems that are in danger; and those that are already prone to diseases like cancer or diabetes. Their down-regulated immune system may appear to be putting up a good fight to try and defeat the invading flu virus (cytokine storm), but in the end, the virus wins and the person with the weak immune system succumbs to the flu virus, or a secondary bacterial infection.

I come from a long line of healthy healers; those that were surrounded by illnesses like tuberculosis, but never themselves got sick. Just because you are old doesn’t mean your immune system is not strong. Many of my family members have lived well into their nineties because they had inborn, robust immune systems. I’ve always been a good healer, just like my relatives before me; my body tends to over-react to almost everything it deems foreign. My case of ME/CFS is definitely not caused by a poor-functioning immune system, but one that is always on high-alert.

Open Medicine Foundation (OMF) and top experts under the guidance of world-renowned geneticist Ronald W. Davis, PhD are launching a bold new project to unlock the mystery of ME/CFS. See the END ME/CFS Project and the remarkable new END ME/CFS Scientific Advisory Board.

http://www.openmedicinefoundation.org/

https://www.facebook.com/OpenMedicineFoundation?ref=bookmarks

All of this sounds very promising! Thank you for the article.

I’m so happy to know Dr. Derya Unutmaz is on board with ME-CFS! His name ‘Unutmaz’ means ‘will not/never forget’. Reminds me of the forget-me-not flower. I pray he lives up to his name and will not forget us until he has done all he can for us. ME-CFS’ers have been forgotten for way too long.

I wanted to post a forget-me-not pic for him…

Thank you so much for this article. The information is so helpful and so hopeful.