“If we lose sight of pleasures … that intoxicate the senses in the most sensuous and beautiful and simplest of ways, then we’ve lost a lot.” – Savannah Page

Researchers have used heat, electricity, chemicals, and pressure to evoke pain in FM patients and controls, and in every study people with FM have felt pain at lower levels of stimulation than healthy controls.

We know, though, that FM is about more than pain. People with Fibromyalgia report they have problems with sensitivity to stimuli in general. They tend to become more fatigued in stimuli-saturated environments, and they tend to retreat to less stimulating environments such as their bedroom. Research studies have borne out FM patients’ experiences, confirming that they are more sensitive to stimuli like heat, sound and touch.

This suggests FM is not just a pain condition, but that the FM patient’s entire sensory apparatus is out of kilter. Just how and why that’s happening is another question. One study finding reduced electrical responses in the sensory cortices of the brain to sounds in FM suggested that this part of the brain was, oddly enough, under-responding to stimuli, not over-responding.

This is a different pattern than has normally been seen with pain. Studies suggest that the nervous system in the brain and spinal cord is amplifying or over-responding, not under-responding, to pain signals in FM.

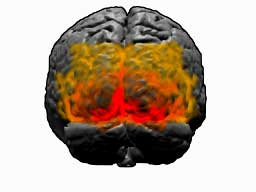

Other studies show that the insula – the part of the brain that integrates sensory inputs from around the body and determines how much attention should be paid to them – is activated in Fibromyalgia patients more than expected. One of the sensations the insula evokes is the sensation of “unpleasantness”.

The findings suggest that a slow initial processing of stimuli in the lower brain regions is followed by a greatly accelerated one in the higher brain regions.

Study

Altered fMRI responses to non-painful sensory stimulation in fibromyalgia patients: Brain response to non-painful multi-sensory stimulation in fibromyalgia Marina López-Solà1, Jesus Pujol2,3, Tor D. Wager1, Alba Garcia-Fontanals4, Laura Blanco-Hinojo2,5, Susana Garcia-Blanco6, Violant Poca-Dias6, Ben J. Harrison7, Oren Contreras-Rodríguez2, Jordi Monfort8, Ferran Garcia-Fructuoso5,6, Joan Deus2,4. Arthritis & Rheumatism

In this study researchers from Spain and Colorado dug more deeply into this intriguing slow-fast sensory cortex-insula effect in FM. Would the slow-fast pattern of processing non-painful stimuli hold? And are the sensory problems in FM connected with the pain people with FM experience, or are they separate?

These researchers used functional MRI to assess the brain functioning of FM patients when they were presented with non-painful sensory stimuli such as sound, light, and touch. Pain levels and levels of sensory unpleasantness were assessed.

Findings

They found significantly reduced responses to the sensory signals when they first hit the brain (sensory/auditory cortices, hippocampi, basal ganglia) and increased activity in the higher parts of the brain – the insula – that integrate both pain and sensory signals together.

[Reduced activation of the basal ganglia was recently found in Chronic Fatigue Syndrome, and similar hypersensitivity to sensory stimuli has also been observed by many ME/CFS patients.]Distressingly Slowed Processing

The study also found that the levels of unpleasantness associated with non-painful stimuli – the sensory overload effect – was associated with and appeared to be coming from slowed initial brain response at the auditory and visual cortices. Somehow the brain’s inability to process normal sensory signals at a normal rate was causing distress.

The fact that the more pain the FM patients were experiencing the more bothered they were with the stimuli suggested that the pain and sensory problems are connected in FM.

If the brain is being under-stimulated by sensory stimuli why are highly stimulating environments (lots of lights, sounds, and people) so bothersome? The paper doesn’t explain why, but it could result from many different kinds of stimuli–none of which the brain is processing particularly well–hitting the central nervous system at the same time.

That could be causing the insula – to prevent itself from burning out – to down regulate the sensory processing regions of the brain. It’s to the insula we go next.

The Insula

Other studies have fingered a hyperactive insula as a key player in the pain problems people with FM face, but this is the first study to suggest the insula plays a role in problems with non-painful stimulation in FM as well. It simply took exposure to ordinary and non-painful stimuli for the insula to flare up in the Fibromyalgia patients.

The insula is believed to be a center of “interoception” and an important regulator of homeostasis in the body. One of the evolutionarily older structures in the brain, the insula is also referred to as a “paralimbic cortex”. As such it regulates basic bodily functions such as the autonomic nervous system, oxygen levels. The insula also controls blood pressure before and after exercise, suggesting that the altered blood pressure variability Dr. Newton found in ME/CFS patients upon standing could relate to insular cortex problems.

In humans, the insula participates in higher brain functions such as the conscious awareness and assessment of how one’s body is functioning. Activity of the insula, for instance, appears to determine how aware one is of one’s heartbeat. In my experience increasing fatigue generally associated with increased awareness of my heartbeat.

A small slice of brain sitting not far from the brainstem, the insula affects both physiology and mood

Overactivation of this little slice of the brain, then, could effect symptoms ranging from sensory overload, to blood pressure problems to mood.

Causes

The study suggests that the problems with over-stimulation in FM are, ironically, caused by reduced, not heightened sensory processing. Why the brains of people with Fibromyalgia are slower at processing sensory signals is unclear, but three ideas stick out:

- Reduced cerebral blood flow in some parts of the brain could play a role.

- The areas of the brain in question could be so depleted of resources (perhaps because of reduced blood flows) that they’re simply not functioning well.

- The higher regions of the brain could also be having so much trouble integrating the various sensory inputs that they’re shutting down the pipelines to them in order to save themselves.

Migraine, Fibromyalgia, and Chronic Fatigue Syndrome

Several factors suggest (at least to me, a laymen) that migraine may present a model for what’s going on in FM and possibly ME/CFS. (Rates of migraine appear to be greatly increased in ME/CFS.) Both sensory dysregulation and problems with blood flows may be occurring in all three disorders.

A similar under/over-activation pattern (in a different part of the brain) occurs in migraine. Decreased pre-activation of the cerebral cortex in migraine is associated with increased hyper-responsiveness of the visual cortex. [Interestingly, this pattern is present in between migraine attacks and normalizes just before they occur and during the attack; i.e. the visual cortex in migraine sufferers is highly activated when migraine sufferers are not suffering from migraines. Is an over-activated visual cortex protective in some way?]

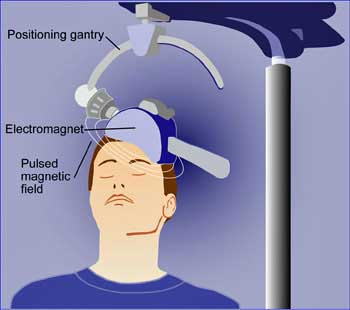

Using transcranial direct current stimulation (tDS) to increase the pre-activation of the visual cortex reduced the hyperesponsiveness in the visual cortex itself, and, more importantly, migraine frequency, and the length of migraine attacks in one study. It also reduced the need for medication. This suggests that “simply” stimulating one part of the brain can cause other parts of the brain to calm down.

ME Blood flow and dysregulated sensory processing problems could occur in FM, ME/CFS, Gulf War Syndrome, and migraine.

Reduced brain blood flows appear to play a significant role in migraine and ME/CFS as well . Migraines appear to occur when nerves constrict the blood vessels at the base of the brain reducing blood flows. As arteries in other parts of the brain open up in an attempt to increase blood flow, they impact the surrounding nerves causing inflammation, pain, and the migraine.

Baraniuk explains increased rates of migraine in ME/CFS and GWS by pulling together dysregulated sensory pathways and blood vessel problems. He proposes dysregulation of the sensory relays in the brain are causing excessive pain (hyperalgesia, allodynia), fearful memories (similar to PTSD), and brain fog, while vascular problems are causing gray matter thinning as well as white matter problems.

Could sensory relay and blood flow problems in the brain characterize many of the so-called functional disorders?

Treatment Possibilities

If under-activation of the sensory cortex is contributing to the pain in FM, the authors suggested that activating it more by increasing sensory stimulation could reduce pain levels. In fact, studies have shown that increasing the right kind of stimuli can reduce pain.

One fibromyalgia study found that simply adding warmth to a painful area reduced pain by about 20%for an hour or so in about 30% of patients. Massage therapy actually gets the highest effectiveness rating of any treatment on PatientsLikeMe for Fibromyalgia.

A recent study finding that a TENS (transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation) unit applied to the spine in FM reduced leg pain, but only when the TENS unit was active. TENS does not always work with pain; it has not proven particularly effective in treating neck and back pain. TENS, or something like it, however, may be more effective in treating neuropathic pain.

A review of electroacpuncture found it was helpful in blocking neuropathic pain in several disorders including diabetic neuropathy. A recent study found TENS, remarkably, was as effective in reducing pain as was local anesthesia in children undergoing dental work, and more effective in reducing their heart rates.

The effectiveness of the TENS unit while it’s active indicates that neurostimulation even in the periphery can be helpful. Ultimately, though, neurostimulation of the central nervous system using tDS and other methods may be more effective.

More study is needed, but this study suggests it may be possible, at some point, to reduce the pain in FM as well by increasing the activity of the sensory cortices that first process sensory stimuli. Whether doing so would reduce insular activity as well is not clear.

This isn’t the first FM study to find problems with processing sensory information.

- Check out Sensory Overload: Study Suggests Brains in Fibromyalgia Are Being Pummeled With Too Much Information

Conclusions

Slowed processing of sensory signals and increased activity of the insular cortex in the brain contributes both to the pain and stimuli issues found in fibromyalgia. The cause of the slowed sensory stimuli processing is not clear, but could result from reduced blood flows, exhaustion of the areas processing the signals, or a deliberate down-regulation of these areas by higher brain regions that are having trouble integrating sensory inputs from across the body.

Increasing the activity of an under-active part of the brain to reduce over-activity of another part of the brain appears to be helpful in migraine, which shares several characteristics with both FM and ME/CFS. More research is needed but a similar approach could potentially be helpful in both disorders.

Heat vasodilates and would increase blood flow. (Heating pad to the rescue.) But there is a fine line as to how much to vasodilate and where. A full body heat up may cause more autonomic response, not in the way you want it to.

I regularly say that “maybe” the uncomfortable responses our bodies do may be for our own good and as a protection to us. Sometimes blocking those responses because they are uncomfortable may be the wrong thing to do. We aren’t getting to the core issue of the problem by treating the symptoms that go along with the problem. That’s like putting a pretty purple bandaid to cover over the owwee. But it may not heal properly and it may always hurt. The pain could be a sign we haven’t properly taken care of the wound.

If we can get our immune systems to recognize pathogens (virus, bacteria and Protozoa all live in a biofilm that can cause the immune system to not be able to detect them) that are not necessary, and irradicate them. Then maybe we won’t have an over response on so many levels throwing off body functions and causing further imbalance. Be it with neurotransmitters, hormones, B cells and/or T cells. And inflammatory substances causing more inflammation and pain. Until we get to the core issue everything is a pretty purple bandaid.

Agreed and good points. There are no home runs out there – nothing that gets to the core. It’s all bandaids – glad to have them – but still bandaids.

It’s really interesting the visual cortex hyper-responsiveness was present when migraine sufferers were not having migraines and then normalized when they were! That reminded me of the sympathetic nervous system activation in ME/CFS and FM and tendency for me to relapse after treatments that calm my system down and relax me…:)

By the way, massage therapy gets the highest effectiveness rating of any treatment on PatientsLikeMe for Fibromyalgia.

This may explain why, when I do lots of mental work for too long, my brain almost feels like it’s seizing up (though not a seizure)–almost like a muscle that’s been worked too hard and is screaming out for relief. Very uncomfortable, creates anxiety, and needs sensory deprivation and sometimes physical movement (walking, etc.) for 15+ minutes to let the brain rest/recuperate. Hopefully the “brain overload” isn’t causing subtle damage to any areas of the brain–need to keep as much as possible while on this planet!

Maybe it’s those arteries squeezing down in the brain? With migraine it just takes the right stressor at the right moment to give the brain a good whack!

this explains clearly why the tinnitus I suffer from is so loud when I have increased pain levels. sometimes it is so loud I can’t hear or understand the t.v. the whoosing/ringing sound is always present, but pain increases dramatically. and when my pain is high, I just cannot think clearly. I never feel out of control in my thinking but clarity of thought and expressing myself verbally is hindered. my biggest pain issues are from my waist to my toes. I do not have migraines or headaches. but my feet and legs hurt 24/7. a hot bath helps with the pain. sometimes I am in the tub 4 or 5 times a day. I also have terrible taste/smell/texture issue , especially with food. when I get overwhelmed , I just stay home and try to sleep.

Ouch!

It all goes together – an important finding in FM…It’s good that sensory problems are getting some play and how interesting that they are associated with a different part of the brain – one that has been hardly looked at.

A big question is whether the sensory cortex problem is setting off the insula over-activation or is the insula knocking out the sensory cortex to protect itself from getting muddled messages…or is something else going on?

Thanks, Cort, for a thought-provoking and well thought out article. Love this brain stuff. I did a bit of reading up on the insula a while back and so I agree with your second option. The part of the insula receiving auditory as well as most of the other stimuli from the sensory cortices is the posterior portion which also receives stimuli from the organs and skeletal muscle via the thalamus which makes me think that the posterior portion is already overloaded with stimuli from the body. The connections between the posterior portion and the sensory cortex are two way so it is possible that the insula is subduing the sensory cortex. However, the anterior portion mainly receives input from the limbic cortex including the thalamus and does get a large input from the amygdala which is also overloaded in our illnesses. It does appear that the posterior portion receives the stimuli and the anterior portion (particularly the right one) adds the emotional component. I also personally think that there is a relationship between the job the insula does in detecting non-painful warmth or coldness of the skin and the extra sensory fibres found near the A-V shunts in the hands. The insula is also responsible for maintaining salience, an imbalance of which can cause either fatigue or anxiety.

I forgot to add that it is dopamine that mediates salient events and that is another problem area for us as you well know. Your reference to the reduced functioning of the basal ganglia (also dopamine dependent) just adds weight to the argument that dopamine plays a big role in all this and is adding to the problem.

I am one that every evening after work I go hide in the bedroom and not want to be around anyone or anything. I can not handle “mentally” someone talking and the television being on at the same time. I can not hear someone when they talk because of other stimuli in the room. I say handle, meaning that I have a flight response. I have to get away from it in order to process what happened. At home, I go to bed; at work, I go for a walk. I do not have pain when this happens. I have fatigue. In addition to FM I have CFS. I believe that it is my CFS that is responding and not my FM. When too many things hit me all at once I simply shut down. I can no longer process and it makes me tired. Would be interesting to find out if stimulating my brain more would actually be an answer to treating the CFS in this instance.

This sounds a lot like me… I have the flight response when I get overloaded… And I get really tired when I have a lot of stimuli…

My brain gets tired and I can’t proscess simple thoughts..

Thanks for listening!

I’m so confused! Everything everyone says here I can identify with (I also have FM/CFS, plus some other goodies), yet some people (my physical therapist in particular) insinuates that our pain is caused by tendon myositis syndrome and in essence, we bring it on ourselves, and therefore can talk ourselves out of it! Even if that were partially true, is it ‘just in our heads’ that some of us who suffered from abuse as children have to learn to ‘heal thyself?’

Gotta be careful. I think some people can reduce their stress levels enough to allow their systems to rebound – but not very many. I’ve been trying it for years! It does help but……even if it works for some people that doesn’t mean it works for everyone. These are complex disorders probably brought on by a variety of factors.

For me – I would try everything you can – you may get lucky 🙂 We’re going to have a recovery stories section that will illuminate the many different ways people can recovery from these illnesses. Some ways are obviously missing – they haven’t been developed yet.

It seems from my experience (and from some other readings) that many of us reach kind of a point of no return. I now realize I was probably coping with these overload tendencies for much of my life — by meditating, avoiding multi-tasking, etc. But then some sort of “event” struck, where I got “sick” almost overnight. It was like a switch had gone off. I’m guessing my “event” was a years-long cumulative build-up of stresses (rather than, say, a particular PTSD-inducing circumstance).

With that in mind, I’m wondering if anyone is looking at pharmaceuticals that might stimulate the lower brain? (If the damage is permanent in some of us, treatments like massage might be temporarily palliative.) Cymbalta has cut my worst burning pain in half, but that’s working on the higher brain, right?

Fascinating read…as well as the comments. I have major depressive disorder, FM and an lupus/rheumatoid arthritis-like auto immune disease called USpA (basically Ankylosing Spondylitis with no fusing showing yet)…and 3 years ago my body started randomly shutting down with rapid onset of complete head to toe paralysis. I’ve been in and out of emergency with all sorts of tests and scans and everything comes back normal. It hasn’t happened for a couple of years but just yesterday I was once again in an ambulance, rushed to the ER with complete unresponsiveness. I am aware, senses heightened but simply cannot move or communicate…and gradually my body wakes up again and I’m normal. Drs are baffled and at a loss as to what is causing this body shut-down. I was a code-blue twice 3 years ago and at that point went unconscious but was revived…no answers. I KNOW stress brings it on, but my dr and I want to get to the root of this – my job involves driving so I can’t work right now as paralysis sets in rapidly (sometimes in minutes). I have symptoms of seizure, stroke and heart attack but all my vitals are fine. Thoughts anyone?

Wow – two thoughts – have you heard of Stiff Person Syndrome? – http://www.cortjohnson.org/blog/2013/03/24/scared-stiff-anxiety-autoimmunity-and-infection-in-stiff-person-syndrome-a-possible-model-for-chronic-fatigue-syndrome/

And you might think about contacting the Rare Disorders Organization – http://rarediseases.org/ – I believe there’s a place where you input your symptoms and tests to see if they match anything. I’m not sure if it’s with NORD or not.

Good luck in your search!

Sherry, my discs have started to fuse and I have severe degeneration, spondylosis, stenosis at all levels so it is inoperable. I have had migraines since my early teens, so 50+ years now. I inherited from my paternal grandmother. I am told my migraines are much more frequent now because the neck situation triggers classic migraine, one side (nearly always the right unless it transitions to the left on its way out), nose runs on one side, vision swims, and eyelid droops on same side. Therefore, I advocate for chronic pain.

What you describe sounds a great deal like hemi-plegic migraine.

http://www.healthline.com/health/migraine-rare-and-extreme-types-of-migraines

As you know, those of us with migraine are at much greater risk for stroke. I hope this information helps you in some way. It must be VERY scarey!

I have ME/CFS rather than FM but was contemplating these findings and pondering my own sensory sensitivity…

With regard to hearing, I know that the auditory system has a feedback mechanism to an amplifier- I believe it is the outer hair cells in the ear. I wonder if the reduced brain activity in response to stimulation is actually causing our “amplifiers” to tune way up? Perhaps the skin and eyes have similar amplification systems.

This whole time I’ve been imagining over active nerve activity in the brain in response to stimulation. But could it be that dampened activity is feeding back to our senses and making amplify?

Makes good sense to me.

Fascinating post as always.

I can’t help but notice how all of the above is also found in those on the autism spectrum, in fact, on my way to my diagnosis of High Functioning Autism (previously Asperger’s syndrome) I was first diagnosed with ME/CSF and then fibromyalgia.

This research reminds me very much of a Centre for Functional Neuroscience I have just started going to. The Professor that runs it is very intelligent. They don’t use fMRIs as so expensive, but use qEEGs to measure brain function ie over and under activity, and aim to rebalance brain function. They also use Direct Current but I’m not onto that treatment yet.

There are centres now popping up around the world if people want to have a Google. Institute of a Functional Neuroscience. Sherry theres one guy I’ve met who had unexplained paralysis and weird symptoms no one could fix. And this fixed him.

I’d love to get an fMRI by no universities in Western Australia do it.

Interesting – thanks Lauren and good luck..

I’m with you on the Dopamine. I’ve been on Mirapex (discontinued because of side effects) and now I’m on Requip. 5mg. at night slowing increasing to where I don’t know yet. I can move better, think better and am probably 50 % more active since beginning requip. (no known side effects yet.) So far this plus Savella and Gabapentin have helped my function the best so far. I can not not try whatever seems to help because I’m a single mom with no chance of retiring anytime soon. So I appreciate you that study FM because I need you for direction on what may help. I also swim every other day for 30 mins. (it’s the best for feeling better after) and walk at least 30 mins. the other days. Haven’t figured out how to stop the foot pain but it could be the weight gain. I crave carbs terribly I imagine for energy. Keep up the good work !!!

Cort, thank you for this! I will be sharing. I am working hard to dispel the 2010 and 2011 Wolfe diagnostic criteria, as are others. Your willingness to explain the research goes far beyond any thanks I can give.

For some reason people have latched on to the 2010 Preliminary Proposed Diagnostic Criteria (Wolfe) this despite a great upheaval and disapproval. The resistance was so great that Wolfe, et al, proposed the “Modified Diagnostic Criteria” in 2011, also met with criticism. It appears most folks are lumping the studies together and calling it the ACR 2010 criteria, even though it was Preliminary, Proposed criteria. The main flaws are lined out in the Jones critique. http://www.familypracticenews.com/news/journals/single-article/acr-2010-criteria-for-fibromyalgia-critiqued/31131c4db6bf3642dd8748c0ad23f08b.html Many believe the disparity is because the 2010 & 2011 allows in Somatic Symptom Disorder (SSD, from the DSM-5), because of what Wolfe calls poly-symptoms. He ignores research that these symptoms are attributive to comorbid conditions to FM, are NOT primary to FM, and therefore should not be considered as FM poysymptomatology. The SSD is something that has MANY pain specialists up in arms, because unlike the previous “somatization,” a physical cause for the symptoms does NOT have to be ruled out in order to make this mental illness diagnosis.

See http://www.huffingtonpost.com/allen-frances/dsm-5-chronic-pain_b_2916904.html

So you see, you digesting this most important research is critical to those of us with FM, CFS, and migraine.

The Bennett, et al, Alternative Criteria (AltCr, 2013, published in AC&R Sept 2014) was constructed and compared statistically to both the 1990 ACR criteria and the Wolfe, et al Modified criteria and it performed far better in some key areas. Here is how it performed:

The 2013AltCr (Bennett, et al.) considers three diagnostically useful symptoms that were not identified in the 2011ModCr (Wolfe, et al.): stiffness, tenderness to touch and environmental sensitivity. The AltCr identified more patients with FM than did the 1990Cr, yet it identified closer to the 1990Cr than the 2011ModCr. I suspect that is because both the 1990Cr and 2013AltCr (Bennett) both require a physical assessment for tenderness. Tenderness cannot be assessed without applying a certain amount of pressure to the patient, not to mention that a skilled examiner can only assess rebound tenderness, non-verbal clues, such as wincing or guarding, and other symptoms that are important to assess, such as listening for hyperactive or diminished bowel sounds. These things are considered objective data, findings by the examiner. The 2013AltCr includes a scientifically evaluated questionnaire to aid in a diagnosis, yet does not insinuate that it alone is sufficient.

As you can see, it is important that we NOT have criteria that encompasses folks with a mental health disorder, which explains why Wolfe’s criteria (Modified 2011 to the PRELIMINARY PROPOSED criteria of 2010) is diagnosing 4 Times as many people with FM than the 1990 criteria.

Piracetam and vinpocetine perhaps then ? To reduce EEG complexity, increase oxygen delivery in brain, vasodilate but only cerebrally .

In a different vane, perhaps what we are looking for has been right in front of our eyes and has been dismissed many times. The Epstein Bar Virus, according to an abstract article in PubMed, can induce CFS as a PAVLOV REFLEX OF THE IMMUNE RESPONCE!

Does anybody know the book: ‘Too loud, too bright, too fast, too tight’ by Sharon Heller? Definitely worth reading!

I developed sensory defensiveness at age eleven, together with migraine (!)after an emotional shock. Only suffered one full blown migraine attack since I fell ill (diet is important); the odd thing was though that, after the attack for one blissful hour, I felt normal.

No, but thank you Ria. Will add to my wish list. Sensitivity is one thing Dr. Bennett found in FM and suggests evaluation as part of diagnosing FM. Another reason I favor his 2013Alternative Criteria published in Arthritis Care and Research this Sept.

Ria,

Do you know if sensory defensiveness has anything to do with Occular Migraines. Occular Migraines does not mean a headache. Does the book Too Loud,toobright,too fast, too tight by Sharon Heller write about this subject with fibromalgia? Please let me know. Thank you. LH

YIPEE!!! I have had FM for 20+ years and still searching for answers. This could explain why I suffer from disequibrium whenever in crowds, supermarkets, etc.

And I thought I had a phobia!!

Thanks so much – understanding the problem is FANTASTIC.

🙂

This is mind blowing Cort! Thank you for bringing this and all the other research you bring to your blog.

Since finally being diagnosed with FM four years ago (having been diagnosed with CFS 20 years ago) I have looked back at my life and believe that I have had this condition or at least some symptoms, all of my life. This study adds more towards this hypothesis.

As a child I was extremely sensitive to noise and was berated and occasionally beaten for the outbreaks of acute distress I exhibited at times. I was prescribed Valium aged 13 in 1968. This was so soothing that I spent over 20 years looking for a magic bullet among prescribed and illegal drugs. My home situation was very stressful as a child. I suffered what the study desribed in crowds just being at home with my family. That is, the feeling of being overstimulated by noise. I have also suffered these symptoms in crowded tube trains – having to wear earplugs and dark glasses to cope with the journey to and from work.

I’m rambling I know, but reading this study makes me emotional. I wasn’t a bad child, I was just suffering! I wasn’t mentally ill – there are now clinical findings to explain my symptoms. How wonderful it is just to refer to my experiences as ‘symptoms’.

I have wondered if some injury was caused when I had surgical release of torticollis? Fifty plus years ago, they will not have considered the implications of cutting through sternocledomastoid muscle with all nerves involved.

I hope the findings will be replicated by further studies. This will be necessary if NICE/SIGN in the UK are to take it seriously. The researchers -Marina López-Solà et al – do not state (unless I have missed it) where the funding came from for this research. As there are no drugs implicated in the study, pharmaceutical companies will not be interested.

Thank you again.

Hey Cort, great article!

It’s been a while since we’ve corresponded. Just wanted to mention that you really liked a couple stories regarding sensory processing that were posted on the following thread at PR about four years ago:

http://forums.phoenixrising.me/index.php?threads/story-eft-for-sensory-overload-and-more.2774/

I just pasted a link on that thread to this article, as I think they complement each other well.

All the Best, Wayne