First I present an introduction to the UK effort –then we’re on to Simon’s blog. I added many images as well as comments (in brackets [ ]). Please note that my interpretations may reflect neither Simon’s or Dr. Dantzers.

The UK CFS/ME Research Collaborative (CMRC) Conference

“By coming together in this way, the application of state-of-the-art research methodology… will greatly increase the chance of identifying pathways linked to disease causation and novel therapeutic targets”

Charities and researchers came forward to form the UK Research Collaborative

The efforts attempt to bring all aspects of the field together, from pathophysiology to psychology, naturally engendered some controversy . Yes, Julia Newton, was there but so was Esther Crawley, who while acknowledging some biological findings in ME/CFS is also overseeing the ME/CFS Lightning Process study.

While the effort aimed to increase the use of cutting-edge technology in ME/CFS (proteomics, metabolomics, pathway analysis, systems biology) and building infrastructure (BioBanks), statements such “important maintaining factors include comorbid mood disorders, beliefs about causation, and either pervasive inactivity or swinging from inactivity to over-activity (boom and bust pattern of behaviour).” made some patients wary and patient opinions were decidedly mixed about the effort.

“Firstly, the collaborative is bringing EVERYONE together who is involved in ME/CFS research – that includes ALL specialties, new and potential researchers, research funding (or supporting) charities, respresentatives of the pharmaceutical companies (in due course) and government (MRC, NIHR, DoH). So the membership will be right across the spectrum from neurology and immunology to psychiatry and psychology…..It is, as I keep saying, a very big tent and the ME/CFS charities that are signing up to join (I think the number is now 7) accept that this is the case.Secondly, it is quite likely that the UKRC is going to play a major role in stimulating new research funding, new research infrastructure (bricks and mortar) and academic acceptance of ME/CFS in hospitals and universities (something that is very sadly lacking at present). We believe it is is better to be inside the tent putting your point of view than complaining about what is happening from outside the tent and (in some cases) trying to drown this initiative before it has even started to swim.”He went so far as to make it explicit that ” It will NOT be promoting psychiatric research in preference to biomedical research. If this was the intention we would not have joined. If this were to ever to be the case we would not want to be a member.” See the rest of his remarks here.

- Check out Simon’s blog on the launch here

Robert Dantzer Lecture

“My research group focuses on the behavioral and psychopathological consequences of the effects of inflammatory mediators on the brain”

Robert Dantzer has been a seminal figure in understanding how inflammation affects the brain

The goal to bring outside researchers into the field was already paying off with Dr. Robert Dantzer, a seminal figure in the understanding of how inflammatory factors effect brain functioning and behavior, presenting. Dantzer has co-authored hundreds of studies on the effects of inflammation on fatigue, depression and pain. (See his review paper “From inflammation to sickness and depression: when the immune system subjugates the brain” for the immune systems effects on depression)

Coming up we’ll have an account of one person with chronic fatigue syndrome who benefited greatly from prescription anti-inflammatories.]

Robert Dantzer Lecture on the Neuroimmune Basis of Fatigue – University of Texas Anderson Cancer Centre – by Simon McGrath

In his presentation, Professor Robert Dantzer explained how sickness behaviour, which includes fatigue, is part of the normal, ‘healthy’, response to infection and usually subsides after the infection. It is triggered by cytokines released by immune cells when they detect a pathogen. Chronic fatigue may be linked to long-term activation of sickness behaviour. Professor Dantzer finishes by describing the ‘orexin’ system in the brain, which may play a critical role in fatigue and could be a target for drug therapies.

“Remember that last time we had the flu — the sleepiness, depressed mood, decreased activity, fatigue, reduced appetite, etcetera? All of this is triggered by cytokines released by white blood cells”. Professor Robert Dantzer is describing ‘sickness behaviour’, the characteristic response of all mammals to an infection. It is a biological process that exists to promote recovery and healing.

Dantzer has been working on how the immune symptoms causes “sickness behavior” for decades

Professor Dantzer’s pioneering research helped reveal the biology of sickness behaviour He now works on cancer-related fatigue, which he believes could be a result of sickness behaviour gone wrong — and which might be related to chronic fatigue syndrome, both in symptoms and underlying mechanisms.

In his model, cancer-related fatigue is driven by white blood cells releasing tiny molecules called cytokines that act on the brain. This process is modified by risk factors, including the version of immune genes you have, neuroendocrine factors and psychosocial factors.

“Previous work on communication pathways between the immune system and the brain needs to guide us”, said Professor Dantzer, as he reviewed the long-running saga of how researchers discovered the relationship between sickness, fatigue and inflammation.

The Brain’s “Immunostat”

Researchers began to realise that, just like any other organ, the immune system is regulated by the brain. There must be what Professor Dantzer calls an ‘immunostat’ in the brain, and much like a thermostat in a central heating system, senses and regulates the temperature, the immunostat senses the state of the immune system and regulates it accordingly. But this requires communication between the immune system and the brain.

Dantzer believes an “immunostat” in the brain regulates immune functioning

Work in the 1980’s found evidence of two-way communication between the brain and the immune system. When they detect infection, immune cells produce molecules called cytokines (Interleukin 1, IL-1, is a key cytokine here). These molecules signal to the brain, alerting it to inflammation in the body. Back then, it was a radical idea that the immune system could produce molecules that affect the brain and physiology. It took a bit longer to discover that these same molecules also lead to changes in behaviour.

More research showed that the communication is a two-way street: the brain controls the release of molecules that regulate the immune cells, including glucocorticoids via the Hypothalamus-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA) axis. (Glucocorticoids are widely used in medicine to damp down inflammation.)

These and other discoveries on the immune mechanisms of fever were brought together in 1988 by Benjamin Hart with his proposal that sickness behaviour is a normal and important process, part of the animals’ deliberate response to infection driven by biology. A key part of the model is that it is a temporary situation to deal with infection: inflammation –> sickness behaviour –> removal of pathogen –> restoration of normal behaviour.

The key steps leading to sickness behaviour are:

- White blood cells recognize invading pathogens. (At this point, the cells use receptors that identify generic ‘foreign’ markers, such as bacterial cells walls, rather than recognising specific bugs such as the flu virus.)

- The white blood cells release cytokines in the body.

- Immune-to-brain communication takes signal to the brain (either via the blood, or the nerves innervating the site of the body in which the inflammatory response takes place.

- This activates microglia – the brain’s innate immune cells – which release more cytokines into the brain. So activation of immune cells in the body leads to activation of immune cells in the brain.

- This leads to more biological changes and, ultimately, to sickness behaviour, including fatigue.

The first evidence that microglia played a critical role came in 1992, when a study showed that microglia produced IL-1 in the brain in response to inflammation in the rest of the body. Subsequent work using fMRI brain imaging shows that inflammation leads to microglia being activated throughout the brain within a few hours.

- [Neuroinflammation: Putting the ‘itis’ back into Myalgic Encephalomyelitis – Back to the Future For Chronic Fatigue Syndrome?

- The Fatigue and Pain Producers: Could Glial Cells Be ‘It’ in Chronic Fatigue Syndrome and Fibromyalgia?

- Microglial Inhibiting Drugs to Combat Neuroinflammation]

Professor Dantzer made the point that while sickness behaviour is normally a standard set of responses driven by infection, it is affected by the environment too. This is the “motivational state” view of sickness behaviour. Normally, when we are sick the world no longer matters to us, what matters is taking care of our injured bodes – exactly what our brains wants us to do – but in extreme situations this can be overridden, as the following experiment showed.

Female mice with young pups injected with LPS at room temperature will show lethargy typical of sickness behaviour, and won’t respond if the pups’ nest is removed. However, if pups are dispersed in the cage, the female mice will overcome their sickness and bring back their pups to the stack of cotton wool they normally use to build the nest.

If the experiment is repeated with the temperature reduced to a chilly 6 degrees centigrade, then the mother mouse will react to the harsher circumstances threatening her pups and not only bring back her dispersed pups to the stack of cotton wool and make use of the material to rebuild the nest. So behaviour depends not just on inflammation, but the environment too. Or, as Professor Dantzer said “Inflammation-induced sickness is a motivational state that reorganizes the priorities of the sick individual”. And those priorities are flexible according to the environment.

Professor Dantzer said that up to this point he’d described normal, ‘healthy’ sickness behaviour. It’s normal to feel sick in response to an infection in the same way it’s normal to feel afraid in response to a threat.

Essentially:

- The brain has an ‘immunostat’ that recognises the immune response in the body – this is the origin of sickness behaviour.

- This reorganises sick animal’s priorities.

- Crucially, sickness behaviour is normally fully reversible.

Then Professor Dantzer moved on to what might go wrong when we don’t recover, asking the crucial question “Is chronic fatigue or depression a form of sickness disorder?”

Inflammation: Unpicking its Roles in Fatigue, Sickness and Depression

“To be healthy is to be able to become ill and recover from it…” (Georges Canguilhem: “être en bonne santé, c’est pouvoir tomber malade et s’en relever”)

Historically, much sickness behaviour research has focused on inflammation causing depression rather than fatigue. However, what doctors call ‘depression’ has different elements, and fatigue counts as a big part of it:

- Mood symptoms including feelings of sadness, irritability and crying

- Affective/cognitive symptoms including self-dislike, guilt and worthlessness

- Neurovegetative symptoms, which include the CFS/ME symptoms of fatigue, problems with sleep and concentration.

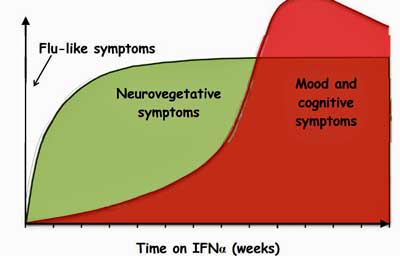

Professor Dantzer showed a fascinating slide based on the work carried out by his former student, Lucile Capuron. This slide broke down how different types of symptoms appeared at different times in cancer patients given the cytokine interferon-alpha as therapy. The fastest response comes from flu-like symptoms (malaise) that appear rapidly with each repeated dose (but fade fast due to anti-fever drugs).

IFN- a, an immune factor released during infection – causes both fatigue and depression

But within a few days the neurovegetative symptoms start, including fatigue, sleep problems and difficulty concentrating. After a week or so both mood and cognitive symptoms cut in.

This means that when researchers said they found ‘depression’ in response to inflammation, sometimes they only meant fatigue and other CFS/ME-like symptoms.

[This collapse of boundaries between fatigue and other symptoms has clearly muddled our understanding of disorders like ME/CFS and depression. We saw how that collapse confused, until recently, the difference between the fatigue and post-exertional malaise found in multiple sclerosis and ME/CFS inAre increased rates of depression found in ME/CFS? Overviews suggest yes. Is ME/CFS distinct from depression? This blog

- “How to Prove to Your Doctor You’ve Got Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS) And Are Not Just Depressed“

indicates that it is. It’s clear that the inflammation Dantzer is talking about can contribute to both mood and other symptoms – in the same disorder . It’s a tangled web.]

A study on an inflammation-linked disorder called Metabolic Syndrome found that there was a link of inflammation with depression overall, but that while there was a significant link for the neurovegetative symptoms, the link with mood and affective symptoms was not statistically significant.

Deconstructing Fatigue – What Exactly Does Inflammation Affect?

Professor Dantzer argues if we really want to understand the biology we need to go further and ‘deconstruct’ even fatigue. The idea is to break it into the ‘neurobehavioural units’ corresponding to the way the brains works. Fatigue, said Professor Dantzer, could be seen as having two elements:

- The physical ability to do things

- Motivation: willingness or wanting desire to do things.

He said that patients they see at his cancer centre have more problems with motivation, but he also believes biological systems underpin both elements of fatigue.

Encouragingly, Dantzer asserted it was time to “deconstruct” the fatigue present in ME/CFS

- See Unrewarding Reward: The Basal Ganglia, Inflammation and Fatigue In Chronic Fatigue Syndrome for more on Miller’s findings]

Professor Dantzer gave the example of motivated behaviour and how it is affected in different ways by different aspects of inflammation. Motivated behaviour can be broken into two steps. In the case of feeding, there is

- a ‘seeking’ phase of accessing the food, then

- a ‘taking’ (or consummatory phase of eating it.

So in predators, like cats, this would be hunting and eating. It turns out that different parts of the brain are involved in theses seeking vs taking steps.

An experiment helped show the difference and how inflammation can affect both steps but at different times. If rats pressed a lever five times (seeking behaviour) they were rewarded with tasty food (the rat equivalent of “very nice wine from Bordeaux” said Professor Dantzer, who is French). The rats had free access to normal rather bland laboratory food (“like wine from Bristol”, suggested Professor Dantzer, who was speaking in a lecture hall in Bristol).

Healthy rats press the lever to get the “Rat Bordeaux”. When rats were injected with a cytokine to cause inflammation and tested ninety minutes later during the peak of sickness, they ate less ‘Rat Bordeaux’ (the food that required more energy-requiring seeking behaviour of lever-pressing), but still ate easy-access boring food (simple taking behaviour). This fits with physical exhaustion.

Mice with inflammation induced fatigue acted differently towards one of their favorite foods – chocolate – than mice with inflammation induced depression

However, the results were different when they did a similar study on mice at a later stage (one day on) where depression would have cut in for mice. This study used grain (unexciting food) or chocolate (which mice apparently love). A single lever press was needed for grain, but ten presses were needed for chocolate. This time the LPS-injected mice injected worked less than healthy mice overall, but more of what they ate was chocolate, even though it was more work. It was if the problem was motivation – they were less likely to respond overall, but if they opted for engaging in an effort, then this effort needed to be for a big incentive rather than a small one.

Similar studies have been done in humans, though they used money instead of chocolate as the incentive. Professor Dantzer said the beauty of this approach was they could study motivation both in animals and humans (and run experiments in animals that wouldn’t be possible in humans).

Orexin – The key to Inflammation-related Fatigue

Professor Dantzer finished his presentation by describing a recently-discovered system in the hypothalamus of the brain that plays a key role in regulating energy levels – and could be a target for drugs to treat fatigue. The orexin system senses metabolic status and the balance between feeding and energy expenditure. It responds to glucose as well as leptin, a key molecule signalling energy levels that has been implicated in CFS/ME).

Is orexin the link between the metabolic and immune (leptin) problems in ME/CFS?

- See Tweeting the Stanford Symposium for more on leptin and ME/CFS ]

The orexin system also plays a role in sleep versus wakefulness. Unlike healthy rats, those given LPS fail to become more active at night. What’s really interesting is that the reduction in activity correlates with reduced levels of orexin. However, rats given orexin as well as LPS don’t show any reduction in activity, suggesting that orexin plays a key role in activity levels.

Orexin as a Treatment for Fatigue?

Researchers suspected that orexin may play a similar role in the cancer-related fatigue resulting from chemotherapy. They found that giving mice chemotherapy did indeed lead to lower levels of activity, indicating fatigue and a reduction in their orexin levels.

Crucially, giving mice orexin alongside the chemo restored their activity levels, again suggesting reduced orexin played a central role in fatigue. He said that there are now drugs for narcolepsy targeting the orexin system, and perhaps they could one day be used for fatigue too.

Professor Dantzer said his group are working on a test of orexin as a treatment for cancer-related fatigue.

Conclusion

Orexin banished fatigue in mice . Could it someday do so in cancer-related fatigue or ME/CFS as well?

Professor Dantzer summed up by saying how hard it was to study a disorder characterized by symptoms, and urged a more detailed approach, probing what is really happening in the brain:

“It’s time now to deconstruct fatigue. We cannot continue to label patients; we have to find out how their brain is working, what is behind chronic fatigue. We are doing that now in cancer patients. There is no reason not to do it in CFS/ME.”

Finally he pointed out the challenge ahead: “We know what causes fatigue, we still do not know what is responsible for the chronification of fatigue”.

This article covers most of the points in the presentation, but does not aim to be a comprehensive summary.

[article by Simon McGrath, thanks to Professor Dantzer for his amendments and approval]

recently died after raising more than £1 million for ME/CFS research.

Simon McGrath tweets on ME/CFS research: @sjmnotes

When clutching the chest with heart attack, vomiting with food poisoning, or pain upon standing after compound fracture to the tibia become referred to as “sickness behavior,” I might accept that term. Behavior is a choice. What patients with have are symptoms.

What patients have with ME are syptoms.

The term ‘behavior’ is technical and correct, if perhaps unfortunate in the context of ME. Behavior here means simply ‘what is the animal (or person) doing that we can observe’.

I mean, this sickness behavior shows up in rats. Do rats have a choice?

Agreed – “behavior” doesn’t really mean “choice”. It’s a descriptive term based on observations that people with colds isolate themselves, don’t move much, feel very fatigued – which means it also includes symptoms.

To me it refers to the things the brain does to stop people with infections from infecting other people.

It is a terrible word in the context of ME/CFS but it has nothing to do with the kind of behavior associated with CBT for instance.

Instead it ultimately refers to immune induced physiological processes and their outcomes that may be very important in ME/CFS.

I would do almost anything to be one of your subjects. This is worse then Fibro Pain etc,.

Very interesting article. Again. I look forward to seeing what the orexin studies in fatigued cancer patients will find. Regarding the several examples of the mice going the extra mile for the chocolate in spite of being fatigued and the mama mouse gathering her pups together as long as they were not taken away, this is exactly the kind of “behavior” (symptoms) I have seen with myself. I will not and cannot cook myself a nice large healthy meal. But have someone put one in front of me and it is history. These are “behaviors” and they are symptoms of our illness. No need to take offense to these words. I’m certain that no matter how terribly fatigued I am that I would stand up and do CPR if someone I knew had a major MI in front of me. That is behavior as well. And young mothers with CFS/ME do not allow their children to starve though they may not even be seeing to their own personal needs. That is the nature of “sickness behavior”; elevated cytokines and IL-1 which cause the immune response. This also affects our brain and subsequently our behavior such as sleeping when we are ill and not being motivated to do anything not completely necessary.

I look at my energy the same way that I look at money – as if it was a form of economics. I call it “energy dollars”, and I only have so much to spend in one day. Some days I choose to spend more energy dollars and go into energy debt. ( Though the reason I can do this in the first place is because my fatigue is moderate and not severe.) I can choose this if I have to – if someone scatters my pups I will go get them ( that said I really felt for those poor mice-mothers, especially since trying to raise my own “pups” whilst feeling very ill). So yes I have some sickness behaviour, mixed in with health behaviour. Lol.

Anyway the energy debt comes with compound interest and takes a lot longer to pay off, but if I keep going further into debt – spending too much, I go bankrupt and can’t spend another thing, even if I wanted to. I guess bankruptcy is the starting point for those with severe M.E/Cfs, so they cannot move much to start with, and get very little choice about where to spend their energy dollars. So I guess calling it sickness behaviour at this level would feel somewhat insulting to the very ill.

I totally “get” the Mommy Mouse Mode – I can “push” and be somewhat energized through important situations (or even “fun” situations) but there is a price to be paid from my energy budget – as you say. If I am very careful, conscious of it, I can generally manage it without a severe crash. But if we must be in Mommy Mouse Mode chronically – gee, no surprise, our symptoms get worse and we can’t recover – we crash. Those of us with moderate symptoms have a little wiggle room for emergencies, and to work on wellness. But if circumstances get beyond what my energy budget can manage, I too have crashed from moderate back into severe. Others are not so lucky – or are stuck by necessity in the push-crash-repeat without recovery, only worsening symptoms.

“And young mothers with CFS/ME do not allow their children to starve though they may not even be seeing to their own personal needs. That is the nature of “sickness behavior”; elevated cytokines and IL-1 which cause the immune response.”

I think that’s a great way of explaining it.Sometimes we make sacrifices – it doesn’t mean that we could do more if we could be bothered, just that in extreme situations we will do more and take the consequences.

Until this idiot can show where the “immunostat” is I think he should shut up. Another theory where the patient is the cause of their problem- I’ll bet cancer patients love this idiot. I think non MD’s should be excluded from ME/CFS research- they don’t even practice real medicine!

There’s no patient blaming here. The same results show up in mice — surely not because the mice ‘want’ to be sick?

This sort of research is exactly what will be helping ME sufferers in the future — getting to the bottom of the relationship between the brain and the immune system (both of which are disregulated).

No, you see this “genius” has “discovered” that when you give cancer patients chemotherapy, that is, when you poison people who are already ill, they feel tired. Sarcasm: Who would have thought?

This “research” is taking as far as I know well-known things about cytokines and adding things about “motivation” in order to get published.

Well– I had to google him to even find out what his credentials are. I just knew he’d be a psychologist. He has a PhD in “behavioral neuroscience” from France. He also is a “Dr. 3rd Cycle, Behavioral Neuroscience,” also from France, I don’t know what that means. He also is literally a vet, which is very funny, also from France. He works at the “Department of Symptom Research” at the MD Anderson Cancer Center, U. of Texas, Houston.

These are his Research Interests:

Behavioral Pharmacology of Anxiolytics

Behavioral Effects of Peptides

Hormone-Behavior Interactions during Stress

Stress and Disease, Psychosomatics

Psychoneuroimmunology

Neuroimmune Communication Pathways from the Innate Immune System to the Brain

Brain Expression and Action of Cytokines

Nutritional Influences on Neuroimmune Communication Pathways

Note the anxiety drugs [funding], psychosomatics [ditto, apparently].

The one and only “discipline” mentioned on his ResearchGate “Info” tab is “Psychosomatic Medicine.”

Dantzer did not discover post cancer fatigue – he merely works on it. Who said he discovered post-cancer fatigue?

I guess if you don’t like psychoneuroimmunology you’re not going like Dantzer or anyone else trying to get at the immunological basis of fatigue, depression, etc.

Yes there’s behavior in there and some upsetting words but notice that virtually every research topic is focused on understanding effects of physiology – from the pharmacological aspects of anxiolytic to hormone-behavior interactions during stress to neuroimmune communication pathways in the brain, to cytokine effects on the brain – on “sickness behavior”.

I think we have to be careful about labels. I don’t like term psychosomatic but when I look at Dantzer’s research it’s about the effects of immune activation and infection on the sickness response.

Worth noting that the one possible fatigue treatment Dantzer mentioned in his talk was orexin, which his group will trial in patients with cancer-related fatigue. That’s purely biomedical and I’m very interested in this study.

The slightly odd think about the psychosomatic angle is that at least historically, and certainly for this talk, Dantzer focuses on work with mice and rats (btw, think that might explain why he’s a vet). And you can’t conclude anything much about psychosocial factors by studying animals. Whereas it is an interesting way to probe the biological factors that might be at play in fatigue.

Wow Greg…He thinks, I believe, that orexin activity in the hypothalmus is where the immunostat is…

I don’t see how the patient is the problem. Dantzer has always been focused on the uncovering the immune systems contributions to fatigue, depression, pain. etc. and he’s suggesting that orexin – not behavioral therapy – may help fatigued cancer patients. Just so you know he’s never done a CBT study. He’s into cytokines not psychology.

It took me a few hours of thinking to be able to articulate a more succinct response. The article says ‘”Inflammation-induced sickness is a motivational state that reorganizes the priorities of the sick individual. And those priorities are flexible according to the environment.'”

Dantzer confuses what the mice can ACHIEVE and what they can SUSTAIN. Almost all of us with ME can achieve a big outing, a big day when life necessitates it. But we can’t sustain that level of activity. What happens in us after we achieve activity of that level is a bigger payback in PEM; in people who can make a behavioral choice, perhaps not. Ours is a symptom, not a behavior. The fact that we can rise to an occasion is no measure of what we can consistently perform. The study assumptions and conclusions are not based in ME.

If he were studying ME, he would be looking at what happens in the hours, days, weeks, and months following his challenge.

I don’t think Dantzer is confused at all: he doesn’t say that the mice can sustain such activity in extreme situations, just that they can adjust what they do depending on needs. Anyone who has been (temporarily) ill and bedbound will know they can do more to get out of danger if their bed was on fire. That doesn’t mean they aren’t ill or are faking it!

I agree that if he was studying ME he would be looking at sustainability rather the response to acute situations. I think its a good point…..it points out how differently you have to approach ME/CFS.

I don’t think he’s confused about that – he’s simply never done that research and I think his point is valid as well – it shows how a response is attuned to our environment.

I thought it was more interesting, though, that as mice move from the fatigue dominated into the more mood dominated aspects of sickness behavior their behavior changes. I wonder if you could determine what kind of sickness behavior a person has – more fatigue or more mood associated – depending on how they respond to an event.

Thanks Cort. Your notes and responses are so well balanced and articulate, and accurate. I so appreciate you bringing these things to our attention – and moderating (literally) the discussion.

I think Carolynn is articulating this very well and I wonder how aerobic and anaerobic metabolism comes into this. I know very well from experience coping with my children that if I push through enough to get a second wind, my goodness to I pay for that later with a massive crash.

I find it hard to believe that the whole story resides in the brain. There seems to be something going on with cellular function and energy production beyond the generation of inflammation related sickness behaviour. Remember Prof Newton’s work, exercising muscle grown from biopsies in the lab and finding many multiples more lactic acid in Me patients than healthy controls.

And what is causing and perpetuating the inflammatory response in the first place – perhaps an illness?

I don’t believe there are simple choices going on here. The mother is making a personal sacrifice of her own health in order to protect her young and will bear the effects later. I don’t see how it’s possible to imply that there will be no physical repercussions from ignoring signals being sent to us by our bodies. In fact many patients have become severely ill through pushing themselves with this illness.

I’m not very focussed tonight so apologies this isn’t as coherent as I would like.

I know, sickness behaviour is a really unfortunate term, especially in ME/CFS where a big school of thought holds that our illness is down to flawed beliefs and behaviours. Sickness Response is a much more accurate term, in my view, and some researchers now use this in place of sickness behavior (eg Younger and Lloyd)

Here’s something I wrote elsewhere about this problem:

http://phoenixrising.me/archives/25148#response

Sickness ‘behaviour’ – or response

The term “sickness behaviour” might sound like we’re dealing with psychological issues, but it’s actually describing an involuntary, physiological response to being sick.

The term was initially used to describe the behaviour of animals who rest and withdraw when sick – because for animals you can only observe behaviour, you can’t measure symptoms like pain and fatigue. But ‘sickness behaviour’ is now used to include the symptoms and underlying processes that drive that behaviour. In fact, Dr. Jarred Younger, a Stanford researcher who believes sickness behaviour may play a key role in the biology of Fibromyalgia and ME/CFS (see part two of the blog), would like to see the term sickness “behaviour” replaced by sickness “response.”

Yes yes yes this guy is on the right travk!

The overly-active immune system, that I was born with, is not possessed by a majority of people. Many people are prone to illnesses caused by a less-than-optimal immune system eg (cancer, diabetes, infections, viruses}. I, on-the-other-hand, react to the extreme to everything my body decrees foreign eg (chemicals, viruses, bacterias). My immune system is innately prone to over-react. It is up-regulated eg (allergies, inflammation, anaphylaxis, autoimmunity). My body keeps sending out disease fighting chemicals, often times, long after the battle is over.

I have known for a very long time that my case of ME/CFS is caused by an exaggerated immune response; that I am not sick in the conventional way that people think of illness. My body is actually over-performing, sending out far too many disease fighting proteins, which at times makes me feel very unwell. Often times, this illness has made me feel not only severe malaise, but also high anxiety and depression. If this is what sickness behavior is, then I suffer from sickness behavior and I am not offended. Sickness behavior is just an exaggerated immune response.

Knowing that my immune system is up-regulated has led me on my own quest to find agents, that help control my ME/CFS. By suppressing my immune response, I no longer suffer the extreme symptoms caused by this illness.

Glad you got at least some relief. How did you suppress your immune response. I would love to know as I know others with this problem…

Hi Cort: I am very reluctant to tell people exactly what I do because what I do is not what would be considered conventional and I am not a doctor. I fear if I tell others all the things I do/take to suppress my hyper-immune-response that I may in some way harm them. I am willing to take the chance for myself, but not others.

What I will say is that I believe my immune system went from being a very innately good one, to being one that went into complete overdrive (up-regulation – autoimmunity, allergic). I suspect that my ME/CFS is linked to dopamine/endorphin depletion/dysregulation and an inability to restore dopamine levels in the brain. Dopamine can act like a brake on the immune system. If you are lacking in dopamine, or have a small storage capacity exercise, stress, illnesses, alcohol etc will only increase the depletion and cause more fatigue, “flu-like-symptoms”, pain, anxiety etc. You become hyper-sensitive and your body starts to over-react to everything. So, the first thing I did was find a way to restore my small dopamine stores with tyrosine and other supplements. This way I am no longer running-on-empty; I now have a useable source.

Everyday, I also use anti-inflammatory drugs (pain-killers), and antihistamines (quite a large dose). I won’t say which ones work for me because they may not work the same for someone else and in fact may harm them. What I do is not perfect, but it has given me a life and I am willing to take the chance. Otherwise, I have no life; only malaise, anxiety and depression.

Sickness “Behavior” – is accurate for the medical research, but VERY unfortunate in the context of ME/CFS because it may imply, to some, personal behavior not the biochemical behavior they are referring to.

How about “Sickness Response” or “Sickness Sequelae” or something like that?

Overall, I find this approach very validating to what I have experienced. It makes good sense to me and follows what my experience have been since my triggering event. I have benefited from certain CBT techniques to help my symptoms, and over time have increased my wellness – but I am not cured. I was already a positive person – and those CBT along with my own personality help me cope. Defining my energy envelope and living in it has helped me prevent the “push-crash-rest-repeat” cycle. If I get outside my energy enveloped even a little bit though, I will crash. I still have chronic pain every single day – which CBT can help reduce along with my narcotic meds. I still must manage my ME/CFS carefully to have a semi-active life. I have slowly been able to increase my activity over time – then plateau and can’t get any farther. I can’t get any “well-er.” Throw in a cold virus, an injury, an infection (such as a tooth) and my symptoms get worse, I get pushed out of my energy envelope through no fault of my own and get MORE symptomatic, and can crash again for months at a time. It sucks.

So guys like this and Lloyd and the Japanese are getting warmer. At last the right direction after so much fluffing around with silly retroviruses etc.

I am really confident we’ll see some treatment options within 3 years

Why if it is a UK study it is always 9 times out of 10 a bias of psychology based theory/research, even if they do dress it up as neuroimmune research it will always it seems, have at least an element of psychosomatic bias to it.

It is annoying, and predictable

I’m not sure what you mean here. Robert Dantzer is based at the MD Anderson Cancer Center, University of Texas

http://faculty.mdanderson.org/Robert_Dantzer/

The one study mentioned on humans is testing Orexin and as anti-fatigue drug in cancer patients. The other studies were on animals, not a good way to look for psychosomatic factors.

People with ME/CFS do not have a problem with motivation. That is not an aspect of the fatigue. They want to do things but can’t do them, at least not without severe physical consequences. I think this is a huge misunderstanding common amongst anyone who has not had the illness and why it is often either confused with or associated with depression.

Also the fatigue associated with other illnesses if not like ME fatigue. Some recent preliminary research showed that the muscles of people with ME produce 20% more than the normal amount of lactic acid on exercise and heal much slower. There is more going on here than just ‘fatigue’.