(In the second of a series of blogs of presentations on the UK CFS/ME Research Collaborative (CMRC) Conference in September of this year, Simon tackles Dr. Lloyds fascinating talk on the how infections trigger chronic fatigue syndrome.

Thanks for Simon’s and Action for ME for allowing us to post his summary. You can find more of their summaries here. I added many of the images and a few of my comments are in italics)

Prof Andrew Lloyd, University of New South Wales- Acute infection & post-infective fatigue as a model for chronic fatigue syndrome.

An innovative study that tracked the development of CFS/ME after several different initial infecctions has revealed surprising findings about the role of the immune system and role of genetic variations in the susceptibility to post-infective fatigue.

The sheep and cattle-farming outpost of Dubbo, four hundred miles inland from Sydney, Australia, was the surprising setting for a key CFS/ME study that put the development of the illness under the microscope. Prof Andrew Lloyd, an infectious diseases physician and immunology researcher from the University of New South Wales In Sydney, has documented the onset of CFS /ME in a tightly-defined subset of patients – and in the process has begun to unravel how CFS/ME develops after an infection.

One of the main difficulties in CFS/ME research, Prof Lloyd argued is ‘heterogeneity.’ All the evidence points to CFS/ME being a mixed bag of patients with potentially differing disease processes giving rise to a similar set of symptoms in all of them.

This diversity has scrambled research findings making it difficult to find a consistent set of abnormalities. In the 1990’s, Lloyd tried to explore this problem by systematically analysing patient symptoms. And indeed, he was able to isolate two broad groups — but even then it was clear that the bigger group was a mixed bag.

Lloyd concluded that the only way to make progress in the field was to zero in on a tightly-defined group of patients to see what went wrong as they fell ill.

Cue the seminal “Dubbo” studies of post-infective fatigue.

Tracking Patients

The basic idea was simple: track patients from the start of an infection and then compare those that develop post-infective fatigue with those that have exactly the same infection at onset but recover promptly. The goal was to see what was different about those who became fatigued and those who did not.

The team deliberately selected three very different infections known to be able to trigger prolonged illnesses:

- Epstein-Barr Virus or EBV – a ‘great big DNA monster’ of a virus that causes the fever, sore throat and tender lymph nodes typical of glandular fever and infectious mononucleosis.

- Ross River Virus – a tiny RNA virus spread by mosquito bites which causes fever, rash and joint pain.

- Coxiella burnettii – a bacterium that causes Q fever, usually picked up from sheep and cattle, which causes a nasty illness with high fever, and drenching sweats as well as inflammation of the liver.

Prof Lloyd had two working hypotheses: the chronic fatigue would be either due to an infection that doesn’t go away, or to an immune system that remains stuck on after the infection is gone. He said that at the time he thought: “It’s going to be one or the other – or just possibly a combination. I’ll sort it out quicktime, don’t you worry!”, a comment that drew much laughter. He also suspected genes played a role.

The key to the study was catching people early. They established good relationships with the local doctors so as to be notified as soon as there was a new case of glandular Fever, Ross River virus infection, or Q fever. Self-report questionnaires and blood samples were collected regularly and those who remained unwell at 6 months were formally evaluated for CFS (Fukuda criteria) using medical and psychiatric exams as well as laboratory tests.

Results

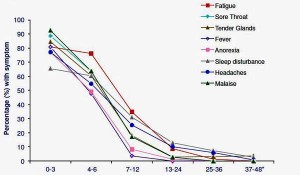

Regardless of the specific infection, around 10-15% met Fukuda criteria for chronic fatigue syndrome at six months, with approximately 6% still fatigued at twelve months, and around 2% remaining fatigued for many years. Overall, this looked like a good model for studying CFS/ME.

Severity of the Acute Infection is Key

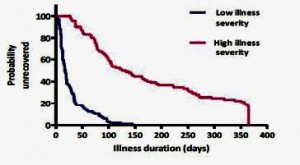

What did predict long-term fatigue (and CFS/ME status) was the severity of the initial illness. For example, the 10% or so of patients who were ill enough initially to be hospitalized had a 200-fold higher risk of having CFS at six months. The graph below shows the huge difference in recovery rates between the third of patients who were severely affected (not just the hospitalised) at the onset or acute phase of the illness and those who were least affected:

Cytokines Can Drive Symptoms

To begin tracking down the differences in what was happening in the bodies of those who developed CFS/ME, Prof Lloyd started thinking about the ‘acute sickness response’, just as Prof Dantzer had spoken about earlier in the day.

What Prof Lloyd calls the ‘sickness response,’ and Prof Dantzer calls ‘sickness behaviour’ are the same. They refer to a biologically-driven, evolutionarily conserved process that occurs across species because it enhances survival value by helping animals or humans to focus on recovery from infection. Symptoms include fever, loss of appetite, muscle and joint pain, general malaise (feeling unwell), concentration problems and, of course, fatigue.

Much as Prof Dantzer wondered if a sickness response gone wrong was a factor in cancer-related fatigue, Prof Lloyd wondered if it could be a factor in post-infective fatigue

Lloyd’s group wanted to revisit the early work on sickness response in animal studies “in the flesh – in humans”, using Dubbo patients. They examined the link between two key pro-inflammatory cytokines, IL-1 beta and IL-6, and symptoms during the early acute phase Q fever patients. And they found the expected correlation between these cytokines and symptoms such as fatigue, muscle pain, poor concentration and malaise.

Looking for Chronic Immune Activation

So then they tracked levels of three key pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-1b, IL-6 and TNF alpha) over time in the blood samples of their post-infective CFS/ME patients and individuals who recovered promptly from the same infection.. Each was known to cause symptoms associated with “sickness behavior”.

With cytokine levels not different between the sick and the recovered patients, the immune activation theory looked wobbly

Despite that fact that the CFS/ME patients were exhibiting symptoms associated with sickness behavior, this hypothesis didn’t pan out: at three, six and twelve months after the initial infection, levels of all three cytokines were no different between fatigued cases and recovered controls. ‘The chronic immune activation hypothesis” Prof Lloyd said “was looking wobbly,’.

Prof Lloyd pointed out that pro-inflammatory cytokine levels that his group had found in patients during the acute phase were present in nanograms per millilitre, which is the level at which they are biologically active.

While some other studies have found elevated pro-inflammatory cytokine levels in CFS/ME patients (unlike his own study), those levels have been in picograms per millilitre, that is a thousand times lower, adding “it is not clear at all that that has biological meaning”.

[Some researchers believe cytokine levels may not be the issue so much as the brains response to those cytokines. Miller with his basal ganglia and Younger with his leptin studies suggest small amounts of cytokines could be triggering a higher than expected microglial response in the brain. In his vagus nerve hypothesis vagus nerve infection hypothesis Van Elzakker proposed a small localized infection at the vagus nerve could be doing the same. ]Looking for Chronic Infection

To test the idea of chronic infection, they simply tracked the persistence of the micro-organisms in the blood over time. They found that EBV, which causes glandular fever, did persist at measurable levels in the blood — but that’s normal for EBV, and crucially there was no difference in EBV levels between fatigued cases and recovered controls.

The Ross River virus and Coxiella burnettii (Q fever) pathogen were cleared rapidly, and again there was no difference in viral loads between cases and controls: the chronic infection hypothesis wasn’t standing on firm legs either.

Cytokine Genes Play a Key Role

If neither chronic infection nor high cytokine levels were causing the CFS/ME patients to remain stuck in their “sickness response” what was? Could the answer lie in their genes. They suspected some people might be genetically programmed to have their immune systems respond more vigorously to an infectious insult. These people, they reasoned, would be likely to become more severely affected in the acute phase of infection and thus have a greater likelihood of post-infective fatigue.

They focused on the inherited variations in genes which encode the immunological and neurological proteins likely to be involved in the sickness response. Specifically, they looked at the genes for five cytokines: the three they’d studied before, plus interleukin (IL)-10 (which inhibits inflammation) and Interferon (IFN)-gamma (which promotes inflammation).

Since high- and low-producing variants of each gene are found, a predominance of high producing gene variants in the CFS/ME patients could help explain why they remained sick while the others recovered.

The results were striking. Patients with the high-producing version of IFN-gamma or the low-producing variant of IL-10 were much more likely to have severe symptoms. The effect was even more prominent in those who had a combination of these ‘risky’ genes. The study showed that:

- those with one copy of the high-producing IFN-gamma gene were more likely to develop severe symptoms than those with only the low-producing IFN-gamma gene, with an odds ratio of 2.6 (where an odds ratio of 1 means no difference between two groups)

- those who had both copies of the high-producing version of the gene were even more likely to have severe symptoms: the odds ratio was 2.9

- those with a double whammy of both high-producing IFN-gamma genes and low-producing IL-10 genes had an odds ratio of 6.8, which is a really big effect.

The team also showed that those with the ‘high-producing’ gene version really did produce more cytokine during the acute phase of the illness. Overall, the type of IFN-gamma and IL-10 genes significantly affected illness severity, cytokine protein levels, and the duration of illness —independent of age, gender and even the specific infection type.

“How long you are going to be remain unwell after these acute infections is at least partly determined by your genetic makeup, in particular those two genes.”

However, these genes only explained some of the difference in illness severity between patients, so while they were part of the story, there must be other factors at play too. The team also looked at neuro-behavioural genes (for example, those that affect levels of neurotransmitters) and reported promising results on one, snappily called P2X7.

P2X7 is a neuro-immune gene that has been linked with psychiatric and neurological disorders. It’s also very important immunologically, affecting, for example, recovery prospects from tuberculosis. And Lloyd’s groups has now found that it may play a role in fatigue.

A cell-surface receptor that appears on both white blood cells and on microglia, the brain’s immune cells, P2X7 helps regulate inflammation, playing a specific role in the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines, including our old friend IL-1 along with IL-18, which stimulates release of IFN-gamma from T-cells. When it’s activated, P2X7 also acts as a pore, allowing transport of the energy molecule, ATP, across the cell membrane.

In Short

Prof Lloyd summed up by returning to his original hypotheses that post-infective fatigue was driven by chronic infection or chronic immune activation. This didn’t pan out: there was no difference between fatigued cases and recovered controls in either pathogen levels or cytokine levels.

The new hypothesis is that “stuff happens” in the acute infection, he said to laughter, though exactly how it happens isn’t clear. Severity of the acute infection predicts post-infective fatigue and our genetic make-up plays a role in both. He said if he had to choose a site where those genes play out, it might be in the body in the acute phase, but in the prolonged phase it’s going to be in the brain. Prof Lloyd added “we need to get over the blood” – the answer, he thinks, probably lies “upstairs”.

Future plans

A new post-infective fatigue study under way (more conveniently located in Sydney) will be looking at autonomic factors and circadian rhythms. And, said Prof Lloyd, they wanted “to really get to the money” – by imaging activated microglia in the brain. (In answer to a later question from Prof Ian Lipkin, Prof Lloyd pointed to evidence in mice that an initial acute inflammation in the body can lead to long-term activation of microglia in the brain. Perhaps something similar is happening in CFS/ME cases that develop after infection.)

They’re using an exercise test and a driving simulation (:)) to provoke post-exertional malaise in their next study

He also stressed the importance of using challenge testing. “If we are to continue to look at the blood, we need to use studies in which we carefully make the fatigue worse – transiently, to look at post-exertional exacerbation”, which he described as being “tough for the patients but good for the scientists!”

They are using a cycling exercise as a physical challenge and, intriguingly, they are also using a driving simulation as a cognitive challenge. Both trigger a symptom exacerbation which comes on over hours and lasts a day or two and then resolves. This offers real opportunities, Dr. Lloyd stated, to look for biological factors which correlate with the changes in fatigue.

It looks like Prof Lloyd’s group is well set up to reveal yet more about how CFS/ME develops after an infection.

- Simon’s first blog on the conference – Dantzer on “The Neuroimmune Basis of Fatigue” – and Chronic Fatigue Syndrome

I find driving games cause major issues. They are more likely to cause me problems than violent games. So using these as a cognitive challenge is interesting.

Post exacerbation testing is the way things are going. However it should also be possible to trigger the same effects in a blood sample when we know more, and avoid harming the patient.

I think the issue that only 2% of patients show long term health problems is important, as its in the ballpark for the population prevalence of ME and CFS.

Yes, I think driving is a really interesting cognitive challenge, especially as it is ‘real-world’ as opposed to a lot of the cognitive tests usually used in labs. Could be a while before there will be a blood test challenge that replaces this!

I agree – driving, particularly in crowded, fast moving situations provides lots of stimuli to sort out…I think it’s going to be an interesting stressor.

Interesting and well-written article, Simon. Thank you.

I was intrigued by the finding on P2X7, particularly in its dual role in regulation of inflammation and in acting as a pore, allowing transport of the energy molecule, ATP, across the cell membrane. Did Lloyd postulate on what that might mean biologically particularly in the context of this disease?

Thanks, Mary.

Andrew Lloyd said very little about P2X7 as it’s unpublished work, and he certainly didn’t highlight the role of ATP in a disease characterised by a lack of energy, intriguing though that is. I’ll be very interested to see how this research pans out.

Sounds like some interesting research. I always wondered why more people didn’t take advantage like Dr Huber at Tufts of those “actively” acquiring ME/CFS like the 1% or so of teenagers each year that get Mono but never recover. I guess her work with the HERV gene never panned out or was more likely canceled by the NIH.

Yes, the NIH HERV study – which had some good pilot data behind it – didn’t work out unfortunately. I think she finished it – but there were no significant results.

Fearful this will lead to us not being insurable down the road. I don’t drive often and only when I am well enough. Already seeing life insurance companies not wanting to insure those with fibro/ME. Great they are studying that though.

At long last some follow up to the interesting results from the Dubbo research…..

Yes, it’s been way too long!

Thanks Simon. That’s a very interesting and clear summary.

I’m intrigued by this P2X7 receptor gene which has been linked to depression and neuropathic pain. It does seem that there is a qualitative difference between the acute and chronic phase and that ‘chronic fatigue’ isn’t just acute fatigue that lasts a long time (if you catch my drift).

Good to see also that Lloyd is looking at the brain.

A similar progression has been proposed for chronic pain whereby the usual brain plasticity becomes ‘ossified’ by pain resulting in a set pattern of maladaptive pain processing :

The Brain in Pain: A Tipping Point?

“Chronic pain is not acute pain that lasts a long time; it is a different state of the brain and sensory system, Apkarian said.”

http://www.painresearchforum.org/news/47180-brain-pain-tipping-point

I can’t see in principle why the sickness response couldn’t have the same effect in a vulnerable population.

“I can’t see in principle why the sickness response couldn’t have the same effect in a vulnerable population”

Makes total sense to me.

Thanks! Yes, this study does seem to highlight an important shift between acute and chronic, and the periphery and the brain.

I do think there are interesting parallels with chronic pain, though remain less convinced by those (including those quoted in that article) that think CBT is the answer – as opposed to a management technique.

Another great article. I really think they are on to something here.

Did they say when the next lot of findings are due?

This fits in with what Dr Goldstein found, does it not? He proposed and used some treatments. Did Dr Lloyd hint at any possible treatments?

What I don’t understand however is how this fits in with the outbreaks (what are the chances that people with these genes are all in the one spot at the same time)?

Why this illness is only recently become more prevalent?

How this fits in with people that recover from treating chronic infections? Mycoplasma, ebv etc.

One more question if someone can answer it.

How would baclofen effect these genes and immune markers?

Thanks!

Didn’t mention when next results or due, or treatment,, though I think it’s too early for that.

>What I don’t understand however is how this fits in with the outbreaks (what are the chances that people with these genes are all in the one spot at the same time)?

What they found was that people in the study had different types of cytokine genes (more/less active), which I think is no different to people generally. And in the study, those with more active inflammatory cytokine genes (or less active anti-inflammatory cytokine genes) were more likely to develop CFS than those with the low inflammatory/high anti-inflammatory genes. This ties in with the more severe initial illness being more likely to develop CFS too (illness severity is governed in part by cytokine response)

>Why this illness is only recently become more prevalent?

Not sure it is – theres a lack of good data on this. Certainly CFS is more recognised than it was, we don’t know if it’s actually more common.

>How this fits in with people that recover from treating chronic infections? Mycoplasma, ebv etc.

Development of CFS-like illness is linked to other acute infections, including the gut parasite Giardia, and SARS and West Nile Virus. It may be a generic problem – the immune system over-reacts and somehow that leads to CFS.

Hi Simon

Yes but no matter what that infection is there are many cases in which people have treated said infection and recovered. That is in opposition to Lloyds theory. ?

That is the essence of his theory. Many people recover, some don’t. Cytokine gene type explains some of the differences: people who produce more inflammatory cytokines are more likely to develop CFS. But that doesn’t explain all the differences between who gets CFS and who doesn’t.

The P2X7 gene is another that might play a role. Initial iIllness severity seems to be a big factor, but what drives illness severity?

What his study does seem to show is that the precise type of the initial infection isn’t too important. Nor are pre-illness psychological factors.

Ok maybe I’m missing something but to me he is saying that an ongoing infection( regardless of what it is) is not the problem, rather it’s the body’s response after the infection is gone.

But there are many cases where people have tested positive to different infections, treated those infections until they no longer test positive to them and have regained their health.

So either there are different subsets where in some it is the body/brain is driving the problems once the infection is cleared and in others it is the ongoing infection that is continuing to drive these problems.

Or maybe he just isn’t finding the infection in the first group?

I’m sure there are many subsets in this illness.

Andrew Lloyd, however, found that people who remained sick were not sick because the original pathogen persisted (there was some persistence in some, but no difference between those who were sick and those who recovered). He originally thought it quite possible the ongoing illness was caused by persistence, but that’s now what the study found.

And to date Ian Lipkin’s work has found no pathogens in mecfs, though that’s mainly based on work in blood plasma, not white blood cells.

Certainly I can’t see anything here that contradicts Lloyds findings, which of course are based on people going down with three specific infections that all have a reputation for leading to CFS in some people.

Hi Simon

So treating the persistent infections that can be found in some patients may stop this process.

It may be the case this theory is correct but it seems very odd that these common infections are in millions of people at any given time around the world but we only know of a small number of outbreaks, like the incline village one.

If these low/high genes are presumably pretty common? it would stand to reason that there would be many more outbreaks and people with cfs in general.

Well, no persisting infection in this cohort so treatment not appropriate in this study.

Nb these are not ‘outbreak’ diseases. EBV/glandular fever is very common among young people, as post-glandular fever CFS, so just as expected. The other two, Ross River Virus, and Q fever are common in the Dubbo area where the study was carried out. I’m assuming the latter two were selected because they do often lead to CFS-like illnesses (which is not that uncommon).

There’s an interesting example from Bergen, in Norway where there was an outbreak of Giardia, a water-borne parasite common in many developing countries. It seems someone got infected abroad, came home with it and faulty sewage system lead to widespread contamination of drinking water. A lot of CFS cases (thousands, I think, or at least hundreds) followed.

You might like to read this article

http://forums.phoenixrising.me/index.php?xfa-groups-thread/invite-to-patient-think-tank-for-uk-biomedical-research-plan-w-jonathan-edwards.1060/&page=1#post-17872

I’m not sure these were as severe as Incline Village which seems unusual eg in cancer prevalence.

I can’t access the article you recommended

Giardia is everywhere, I think. Long ago when I first backpacked in the US Rocky Mountains, we could drink the water from the fast moving streams and any springs we found, in the back country. A few years into that fun part of my life, giardia was in the wildlife population so we had to filter all the water we drank, and every drink of unfiltered water from a high altitude, fast flowing stream was taking a huge risk, because the wildlife travels where it will and has no concern about clean water in the mountain streams.

Then I got this disease and that ended my backpacking career. Hiking, bicycling and now it seems walking careers are gone now.

But the towns and villages around the Rocky Mountains had to change their processes for distributing clean water in pipes to homes, because chorination did not kill giardia only fine filtration. I remember reading about the cost to the towns, once people started getting giardiasis from their supposedly clean home tap water. And I remember my two friends who got giardiasis from a bakcpacking trip, how very thin they got, how long it took for them to get better.

So I would not brush off giardia as a problem of the under developed nations. It is a US problme too.

More on topic, I am glad that the Dubbo studies are being followed up, as those seemd to have such a good design to answer major questions about this disease.

Sarah