(This blog is taken from three sources. A radio interview with Jarred Younger, information on the University of Alabama at Birmingham website and an interview I did with him. Thanks to Jarred for his time.)

Unlike others, Younger was never phased by the lack of attention given fibromyalgia and chronic fatigue syndrome. In fact it was something of a spur to him. He started studying fibromyalgia twelve years ago when little was known about it. He found the field intellectually stimulating because little was known about it and because so many people had it. It was a field, he felt, he could make a difference in.

He’s a new breed of researcher – a researcher who started out and stayed in this field. He placed a big bet – his career – on FM and ME/CFS and that bet appears to be paying off. Hopefully other younger researcher will take note and follow.

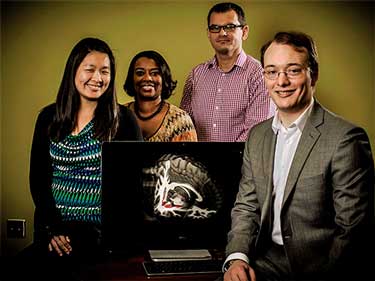

His road most recently lead from Stanford where his pioneering studies into the effectiveness of low dose naltrexone and fibromyalgia opened a new treatment option for many to the creation of his own Neuroinflammation, Pain and Fatigue Lab at the University of Alabama at Birmingham. The lab is engaged in wide variety of projects, many of which revolve around the subjects of inflammation and neuroinflammation.

Neuroinflammation and the Microglia

In a recent interview Younger described a remarkable shift that’s occurred in the pain research community. Seven years ago, he said, there was almost nothing on the microglia in the pain conferences. Now they’re loaded with presentations on them.

He demonstrated how microglial activation could contribute to a wide variety of diseases. The microglia are extremely sensitive cells. They’re sensitive to so many factors, in fact – they have dozens of different types of receptors – that they can be triggered in many different ways. Anything that activates the immune system, and that means any stressor – from an infection to psychological stress over time to taking in any number of toxins – could potentially trigger microglial sensitization in the right individual.

They can be triggered in many ways but the microglia can produce so many different chemicals that each trigger or collections of triggers could result in a slightly different response. Those differences could manifest themselves in more fatigue in one person, more pain in another, another anxiety in another, etc. The difference between ME/CFS and FM and other disorders could come down to a slight differences in the ratio of the chemicals the microglia are putting out.

First I asked if two of important studies in ME/CFS – The Dubbo studies and the Lipkin/Hornig cytokine studies might be showing the same thing. The Dubbo studies suggested that more severe symptoms and higher pro-inflammatory cytokines early in an infectious process predisposed people to come down with ME/CFS. On the longer time-scale Lipkin and Hornig found higher rates of inflammatory cytokines earlier in the illness and lower rates of cytokines later in the illness. Are both studies, albeit on very different time-scales, highlighting a period of increased inflammation which resets the microglial activity in the brain?

Yes, both sets of results support the hypothesis that a significant immune event or series of events can sensitize the immune system. The shift from high cytokine expression early in the disease course to low cytokine expression in later stages may represent the “chronification” of the inflammatory response. At that point, the inflammation has migrated to the central nervous system where it is harder to detect with normal blood tests. Because of the separation of the brain and body, sensitized microglia could continue to drive fatigue even if the immune system in the body appears to be operating normally.

Acute onset ME/CFS and FM is well known. Many people can remember the day everything changed. A survey Health Rising suggested that that some people can become well and then relapse just as quickly as others became ill. I asked Younger if acute onset or relapse fits into the microglial hypothesis? Can they become enter into a state of chronic activation quickly?

Microglia need only a few minutes to change from their resting state to their activated state. There is some evidence they can move back into their resting state just as quickly. If we inject a human or animal with lipopolysaccharide (LPS, also known as endotoxin), we will see a full activation of microglia very quickly. So, it does seem plausible that an individual could experience symptoms that come and go very suddenly. The symptom severity at any given time may just represent the degree to which the microglia are activated.

Until we find out more about how microglia are triggered, it may be useful for individuals to track any environmental, behavioral, and dietary factors that may have causes their symptoms to get worse or improve. Those quick fluctuations may hold the key for understanding how to manage the disorder for any given individual. We have applied for a grant to work on a new tool that will make that process much easier. It will automatically analyze data that the participant provides and find important cause-effect relationships that may be too complex for us to detect on our own.

I asked Younger if chemical sensitivity might be caused by microglial activation. “You mentioned diesel particles sensitizing the microglia. Could multiple chemical sensitivity be a microglial sensitization disorder?”

It is possible, and especially likely if the individual experiences fatigue, cognitive disruption, and other symptoms classically attributed to microglia activation. Unfortunately, chemical intolerance is a poorly researched phenomenon. There are probably multiple routes by which inhaled chemicals can make someone feel sick, and not all of them would involve microglia.

The neuroinflammatory hypothesis for FM and ME/CFS makes sense in so many ways but it’s still almost entirely unproven. So far as I know just one study, thus far, has looked for it (and found it) in ME/CFS. I asked Younger what would it take to convincingly demonstrate that neuroinflammation is at the root of chronic fatigue syndrome and fibromyalgia? What kind of evidence would be needed to show that?

There are two things that need to be demonstrated. First, we need to show that a brain imaging technique (like the brain thermometry tool) can reliably detect neuroinflammation. We could do that by seeing if the imaging technique is sensitive to microglia activation caused by the injection of endotoxin.

Once we have a validated brain imaging technique, the second part is to administer individuals with FMS or ME/CFS a drug that we suspect reduces inflammation in the brain. If we see that giving that drug reduces the symptoms AND it reduces the neuroinflammatory signal on the brain imaging scan, then we will likely have adequate support for the idea.

The search for validation has been a long one for both ME/CFS and FM. I asked Younger if he and others can convincingly show states of neuroinflammation are present in ME/CFS and FM patients how would that change things? How would it change things for your program and how would it change things for ME/CFS and FM research efforts?

It would change things considerably. The primary difference would be in the therapies being developed, tested, and used. The scientific and medical communities would focus less on drugs that target the nervous system, and instead start trying existing and new anti-inflammatories. For example, researchers may modify current anti-inflammatories so that they can pass the blood brain barrier and reduce neuroinflammation (most anti-inflammatory medications used today cannot get to the brain).

Younger is developing an entirely new way to measure neuroinflammation. He hopes to begin ME/CFS and FM studies early next year.

Health Rising recently published a blog showing the scores of different techniques researchers are using to try and measure neuroinflammation. (see “The Brain Game”. I asked about how he’s going about measuring it. It turned out that he’s using a different methods from all the others detailed in that blog. He expects to have it up and running and using it to study ME/CFS and FM patients soon.

We are currently working on a technique called magnetic resonance spectroscopic thermometry (MRSt). The technique uses a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scanner to non-invasively determine brain temperature. It will essentially act like a thermometer for the brain. When our immune system is activated in the body, there is an increase of temperature. We believe the same thing happens in the brain. Once we are finished, this tool may be able to detect when someone is suffering from neuroinflammation. We expect to have the tool ready by the end of this year, and we will likely start recruiting individuals early in 2016.

Effective treatments are, of course, the ultimate goal. Studies suggest that some antibiotics and antivirals as well as LDN and herbal preparations may all have microglial inhibiting properties. But what about new drugs? Are new drugs being specifically developed yet to rein in over-active microglia?

Absolutely. Many groups are working on new microglia modulating compounds. There are dozens being tested right now. Some of those promising agents push the microglia back into their resting state, while other agents push the microglia into an alternative, neuroprotective state (called the M2 state). Any one of those agents may be very successful in treating ME/CFS or FMS.

Unfortunately, the process of developing a new pharmaceutical, testing it for safety and efficacy in animals, and progressing cautiously in humans takes many years. Also, there is no true FMS or ME/CFS animal model. So, there is a big risk that we will miss an important drug only because animals did not respond well to it. For those reasons, it is critical that we test currently-available compounds that can be used in humans much more quickly.

I asked Younger how he was testing possible microglial inhibitors?

Our technique for testing microglia inhibitors is fairly basic. We read the scientific literature to create a prioritized list of compounds to try. The compounds with the most convincing basic science support (typically in cell cultures or in animals) will be placed at the top of our list. Then, we give those compounds to individuals with ME/CFS or FMS in a closely-monitored clinical trial. We are going to be testing several such compounds this year. Participating in a clinical trial is sometimes the only way to try new medications before they are available to the public (usually a few years in advance). But they are also typically more risky because we haven’t collected as much safety data. We do our best to pick only those compounds that seem to be safe.

Low Dose Naltrexone (LDN)

The LDN/Younger story is an example of a newer breed of researcher being willing to step beyond the normal options. Younger initiated the first and to this day the only LDN studies in fibromyalgia. Those studies have made a world of difference of to the many FM patients who’ve benefited from the drug.

Younger believes LDN is probably calming down the microglia that release chemicals that make you feel horrible. HE noted that small unpublished studies suggest that no less 65% of FM patients respond well to LDN. Originally, it was thought best to take it before bedtime but he found that it works as good when taken in the morning as at night. It does not have to be in your body to be helpful. Even when someone stops taking it it takes them about a month to get back to baseline.

An Australian post doc working in Younger’s lab found that LDN reduces inflammatory factors in the blood. If so it’s doing so in a way that has not been seen before. The next step is to do brain scans before and after LDN administration.

Showing LDN can reduce brain inflammation would be a huge step forward for it. We saw recently that researchers are scrambling to develop ways to assess levels of inflammation in the brain. Once they do that the next step will be to try and reduce it. If LDN turns out to be effective at suppressing neuroinflammation it may finally start getting the study it deserves.

Opioids and the Microglia

Most doctors use opioids to treat chronic pain. While they’ve effective for some they can also come with some serious and sometimes paradoxical side-effects – one of which is increased pain sensitization. I asked him about one of those:

In an interview you noted that opioids sensitize the microglia. Does the ability of opioids to put the microglia on a hair trigger explain the seemingly paradoxical and troubling pattern of long term opioids resulting in hyperalgesia – increased sensitivity to pain?

Exactly. While the exact mechanisms are being worked out, some great work by Linda Watkins, Mark Hutchinson, and colleagues have shown that opioid administration can drive hyperalgesia via activation of microglia. Those findings open up the exciting possibility that we can block the microglia activation and therefore prevent the negative aspects of opioid use, while still receiving the beneficial effects of opioids. That system has not yet been developed successfully for humans, but groups are working on it.

Do you know in what percentage of long term opioid pain drug users become more sensitive to pain over time?

We don’t really know. The only way to know if someone develops hyperalgesia is to track them over time. It likely develops slowly over time, and may not even been noticed by the patient. Someone who seems to be hypersensitive to pain is likely to be told that their original pain condition is just getting worse, or the pain is “generalizing”.

Very few physicians have access to the pain testing equipment needed to track the development of hyperalgesia. I have not seen a single study trying to identify the percentage of pain patients who will develop opioid induced hyperalgesia. And while we know it happens, we don’t know if it is a severe problem or just a minor nuisance.

Individuals taking opioids should note if they start to develop pain all over their body, especially if they have been taking higher and higher dosages of painkillers. Some good news, though, is that we have found simply reducing the opioid dosage can reverse hyperalgesia in many patients.

Younger proposed one scenario – and it’s only one – which could explain the post-exertional experienced by some people. The increased blood pressure that occurs during walking or exercise is known to release endorphins. Ordinarily those endorphins should make you feel better, but if the microglia are sensitized to endorphins; i.e. if they get activated by them – those endorphins could trigger the opposite – feelings of fatigue and pain that last for several days.

That’s just one possibility. It may not be happening at all. The point is that the microglia are such central actors in the brain they could be tweaking it in ways we’re hardly aware of now.

Inflammation

At some point the pathways producing fibromyalgia and ME/CFS will be clear and treatments will be developed to fix them. Until then, Younger believes the key to treating ME/CFS and FM probably revolves around reducing inflammation. Inflammation, in particular, central nervous system inflammation, is something that we as a society have not been taking seriously enough.

The term inflammation is probably going to broaden significantly over the next five years as researchers find it in new places and and find new ways of measuring it. Dr. Montoya recently noted that the typical measures of inflammation used – SED and CRP tests – don’t pick all kinds of inflammation. The most common anti-inflammatory, aspirin has no effect on neuro-inflammation. More fine-tuned ways of testing for and battling inflammation are emerging. Ultimately the crush the immune system ethos of the steroid era will disappear.

The effects of inflammation, particularly neuroinflammation has been under-appreciated but that is changing.

Younger believes low amounts of inflammation should be battled rigorously lest they trigger a kind of system reset that results in ME/CFS and fibromyalgia. People with osteoarthritis, for instance, have an increased risk of getting FM. Why? Steady pulses of inflammatory/pain signals increase the possibility of some switch getting flipped that causes a widespread pain sensitization.

Younger’s earlier study suggested leptin may be a big player in the inflammatory milieu in ME/CFS. He noted during the interview that women have three times the leptin levels that men do. We still don’t know enough about leptin yet to conclude it’s the key – further studies need to validate the findings- but if leptin is a player then cutting down stress eating., losing body fat, exercising at a very steady and light rate and eating low glycemic and staying away from high carbohydrate diets could help a bit.

Depression is another disease that probably has a central nervous system inflammationn component. Younger believes depression may not be so much low levels of brain chemicals like serotonin or dopamine as it is brain inflammation. The reason it’s taken so long to gloam onto that is because it’s been so hard to measure brain inflammation. That is changing.

Other Research

The Lymphatic Brain Network

Health Rising recently a published a blog on lymphatic network recently discovered in the brain that may provide a new window on whats happening in many neuroimmune disorders. I asked Younger how researchers will go about using it to study disease? Is it accessible? What kinds of studies should we expect to see and can we expect to see any from you?

It won’t be easy to study because it is still on the inside of the skull, and therefore inaccessible to direct investigation in living humans. Some researchers will use animals to see if inflammatory agents can somehow make their way to the brain via the lymph system.

I think the most exciting aspect of the lymph system is that it could be a way to monitor the brain without actually having to get to the brain. The lymph that drains from the brain down through the neck is carrying everything it picked up from the brain, including inflammatory agents.

If we can sample the lymph in the neck, we could see what is going on inside the brain. But it will be much more easily said than done. The researchers who found the brain lymph system suggested that those vessels run very deep in the neck. They are likely behind both muscles and lots of nerves, so it may be too dangerous to try to reach them with a needle. We will see what is possible.

I asked Younger about a small study he’s doing on alcohol, fibromyalgia, and the immune system. Alcohol intolerance has been one of the very distinctive but wholly unexplained aspects of ME/CFS/FM for me since the disease began. To me this study also exemplifies what a creative researcher with his/her own lab can do. It also indicates that Younger is well plugged in with the ME/CFS/FM communities as this issue is rarely mentioned. I asked to say more about the study.

I thought to study alcohol intolerance because the majority of ME/CFS or FMS participants in my studies were reporting that they almost never drink because they don’t like how they feel afterwards. Alcohol intolerance is almost never studied medically for one simple reason – people who suffer from it just need to avoid alcohol. Also, many people don’t like to drink alcohol because they lack the enzyme to metabolize it properly – allowing toxins to build up and make them feel ill.

Obviously, I think alcohol intolerance (in people who have the proper enzymes) may help us understand the pathophysiological mechanisms of ME/CFS and FMS. Recent research shows that drinking alcohol does set small-scale inflammatory processes in motion. If individuals with ME/CFS or FMS have sensitized microglia, that small-scale inflammation may turn into large exacerbations of symptoms.

The kynurenine pathway is upregulated in many central nervous system disorders and there’s some evidence that it’s upregulated in fibromyalgia as well. Do you plan at any point to look for evidence of kynurenine pathway upregulation in FM or ME/CFS?

It is an interesting hypothesis that would tie together a number of different disorders that share some features. I will keep my eye on any new work in that area, but we don’t have any plans to investigate it specifically any time soon. We have to stay focused on our primary line of research in order to quickly either turn it into a productive treatment, or rule it out and move on to the next idea.

Younger’s Neuroinflammation, Pain and Fatigue Lab and the Future

“Without a doubt, the biggest obstacle to successfully completing a human research study is recruiting the participants.”

Younger worked at Stanford until the University of Alabama at Birmingham sought to become a leader in ME/CFS and FM in the South and reeled him in. Younger said he’s been given a lot of resources and has been able to grow his lab very quickly. He said he’s gotten a better response at UAB at Birmingham than in Stanford.

I am not surprised. Younger may have to face fewer headwinds at UAB than Montoya does at Stanford. UAB with Younger, like Nova Southeastern University with Dr. Klimas, appears committed to making its mark in the field. The Stanford program, on the other hand, was jump started by outside donors. Montoya appears to be getting excellent support from his colleagues now but can’t yet work full-time on ME/CFS. Klimas and Younger are working full-time in labs dedicated to these diseases.

Ron Davis has been proposing that advances in ME/CFS are going to open up understanding of other diseases. Do you feel that’s true for ME/CFS and fibromyalgia and, if so, how?

I believe that many disorders are at least partially driven by brain inflammation, so I definitely agree with Dr. Davis. Any treatment found to be effective for ME/CFS or FMS should be immediately tried in the other disorder. The same goes for: Gulf War Illness, irritable bowel syndrome, major depressive disorder, cognitive problems after traumatic brain injury, fatigue from rheumatoid arthritis, fatigue due to cancer treatments, and dozens of other conditions. I also believe neuroinflammation drives many symptoms of normal aging, such as increased fatigue and decrease cognitive functioning. An effective and safe anti-neuroinflammation agent may become something that almost anyone could take, similar to how aspirin is used by so many people to help control peripheral inflammation.

I asked him how the fibromyalgia and chronic fatigue syndrome communities could support him in his work?

Thank you for asking. Without a doubt, the biggest obstacle to successfully completing a human research study is recruiting the participants. Every study we conduct requires people, both ill and healthy, to dedicate their time to the project. No new diagnostic techniques and no new treatments can be developed without those individuals. We are especially grateful for those participants when the disease itself makes coming to the laboratory so difficult.

We have had a great response from the community since moving to Alabama, and have a good list of individuals who are interested in participating. But as the laboratory grows, the studies will grow as well, and we will need more and more people to volunteer. So, the best support people can give is to participate in studies if they can. We completely understand that sometimes people are just too sick to help in that way. The next best thing they can do is get the word out to as many people as they can whenever we have a new study or research finding.

As our group becomes more nationally and internationally recognized, it allows us to attract more participants, more donors, and more resources. I think it is very likely we could leverage that reputation in the future to develop a large, interdisciplinary research center specifically for these disorders, and start studies that operate across the United States to reach as many people as possible. We are on track to make those things happen, so I am very excited to be in the position I am in.

- Sign up to get updates from the lab here

- Help the lab decide what video’s to use in an upcoming study.

Here are some of the studies the lab is engaged in now.

- Discovering the source of chronic pain and fatigue – to produce diagnostic tests for ME/CFS and FM

- Daily immune monitoring in men with Gulf War Illness

- Using botanical anti-inflammatories to treat Gulf War Illness

- Developing better methods for detecting inflammation in the brain

- Exploring the effects of opioid painkillers on the brain

- Examining Low-dose naltrexone and other microglia modulators for pain

- Assessing alcohol intolerance in ME/CFS

I have been taking LDN for almost 7 years. I learned about it in a book I read “How to Reverse Immune Dysfunction”. It was written by an AIDS patient that cured himself. I cannot think of his name. I probably will in the middle of the night. I took all the research I could find to my GP, and another doctor. They both were very interested and I got a script right away. I was already taking it when I went to Dr. Klimas, she had some questions and I know she is using it and may have been some before I went there, not sure. I saw Dr. Rey last month and she is all for it too.

In the 96 I actually spoke with Dr. Bahari. I called his office and he answered and I told him my story. He had found that AIDS patients with other infections were getting better. His daughter had MS and he decided to try a low dose on her. She went into remission. He sent me a scrip but I had no idea what I was doing and took the one bottle but was so sick then I could not tell and did not renew it. Time went on and I was hearing more about it from the wife of a Parkinson’s patient and I read everything I could. I knew I wanted it and it was very easy once these two doctors read the material. I know they started using it on other patients.

I started at 1.5 at night and worked up to 4.5 all at night. When I went to Dr. K she said why not take it in the morning and at night. She suggested 3.0 and that is where I am. It has helped me a lot but not so much when storms are around like today. It has helped my mood a lot. I want to do things and have to be careful and pace…hard for me. People think I am totally well, LOL I can live a normal live now but I am careful; and have an almost perfect plant based diet. I have also done a lot of detoxing and lymph drainage.I drink a lot of green drinks. I eat organic and locally grown veggies. I do eat meat…. grass fed once a week. Chicken is free range. I love salmon and have it often. I think we are all very toxic and we deal with more than the body can handle every day. I just read 70,000 new chemicals since WW2 and they are not tested and don’t have to be. The tests usually come from the manufacturer.thanks to a law that was passed and was again I think. It was called the DARK act and it sure fits..

I changed all household cleaning items and makeup. Funny how vinegar and water can make stainless steel shine better than anything. I mix peroxide and a green dish soap for other cleaning.

I think LDN is going places.

Thanks Cort for reporting on this.

Thanks for telling your story. One thing I’ve learned from hearing about people experiences is that it really is important to start low 🙂

LDN may be the tip of the iceberg once the ability to measure neuroinflammation becomes established – and it shows up in lots of diseases….Watch the drug companies go nuts trying to figure out ways to calm the microglia down. It’s going to be interesting!

Marg,

Thanks for the info on LDN. I hope to try it. You said a number of important things, but one that stands out in my mind – the fact that the LDN does not help as much when there are big storms around – ie low pressure systems.

I also have a problem with problem with pressure changes – ie airplane flights. A quick stopover causes even more problems on the second leg of a flight. I also feel the low pressure systems.

Have you ever seen the old fashion barometers ? A glass globe with a long goose neck curving thin tube at one end? Well, it is amazing to watch how pressure changes in the atmosphere affect the height of the water in the tube.

I am voting that it is fluid dynamics in the central nervous system that is the main issue for many of us. I am so grateful that Dr. Younger is investigating The microglia and inflammation. However, I keep hoping some researchers will look at structure and function and how this influences fluid dynamics in the CNS.

Excellent blog. Well done.

A word on inflammatory markers. I have often stated that in iron replete patients, that is, in patients with ferritins in the 150-180 range, ferritin levels rise and fall in response to TNF-alpha and IL-1beta. Inflammatory relapses are thus readily recognised. I am looking at minocycline, a brain penetrating IL-1beta agent, to see how effective it is as an anti-inflammatory agent and how well it helps patients symptomatically. Falling ferritins seem to reflect clinical benefits.

Curiously, C3 levels are also useful and full on activation of this, raises C3 by 30% from blood baseline levels. This too is a useful easy to measure immune marker that helps in determining immunological relapses from non-immunological / non-inflammatory ones.

Blood Beta-2-Microglobulin levels are often elevated as well in CFS/ME patients, but noting a pattern that correlates with wellbeing so far, does not appear to be the case.

Again, excellent blog

I use clarithromyacin for its anti-inflammatory properties. Helps immensely. Tried doxycycline with no effect.

LDN works in two ways…by reducing inflammation and boosting endorphins. If boosting endorphins through walking can be a potential cause of PEM, how is the same activation of microglial cells not happening with the use of LDN? Do the antiinflammatory effects just tend to outweigh any microglial activation from endorphins?

I would like to know the answer for this too.

I tryed a very low LDN (0.5mg at night) and it made me feel extremely ill….

I did some trials of about 7 days each one but finaly I had to stop it and. It was very sad b/c I had great hope about it.

I don’t know…..I do know that Younger doesn’t believe endorphin angle really applies to ME/CFS and FM – he thinks LDN is beating down the microglia instead. I don’t how he came to that conclusion. It sounds like we’ll know about the microglia/inflammation side of it in a year or so.

I know inflammation is a very complex process…(my naturopath once showed me a diagram of inflammation and it filled an entire page with arrows and boxes)….but, if on a very basic level, neuroinflammation is like inflammation in other areas of the body – hot, red, swollen, and tight – it makes me wonder if the POTS (and fast heart rate) that so many of us experience could primarily be a compensatory method to assure that enough blood gets pushed into an inflamed brain (and/or blood vessels). It seems like this would be an essential life-saving mechanism.

That is how it has always felt to me from the inside – almost like the pressure above my neck and below were different – my heart working hard to fuel what still felt like an under-oxygenated brain. And this is how inflammation is viewed in other tissues (like muscles, for example) – that it prevents proper circulation, and therefore, proper oxygenation, fluid and nutrient exchange, and waste (toxin) removal.

Also, the POTS was one of the very first patterns to disappear once I started taking LDN.

Just a thought!

What we have here is inflammation WITHOUT the classical sign of inflammation. We don’t see standard infiltrates of white blood cells, oedema and so on. Inflammation of the kind we speak of here, is much more secretive or silent.

I totally agree that there is a diminished supply of glucose and oxygen to the brain, but only by a small margin. The decreased blood supply may impact acutely, as in ‘I must lie down NOW’, on the one hand, versus a more insidious depletion of brain nutrients, such that hypoxia brain injury builds up whilst in the upright position so that that days to repair the damage are required during the post exertional recovery period.

How independent the processes of brain inflammation and brain hypoxia are is a big question. My guess is that they are interrelated both (a) pathophysiologically and (b) phenomenonologically, but to some extent, are they are still independent partners in crime.

One might fix brain inflammation OR fix orthostatic intolerance, but if both are not addressed, problems will remain.

I guess to my mind, even if you were to have only 100th (or even 1000th) the amount of physiological (tissue) changes in the inflamed brain as you do in a finger that has been hit with a hammer (for example), the body would undoubtedly see such circumstance as a major threat – due to the vital importance of the brain for the function and survival of the organism. And if that inflammation were to become chronic, it could have all manner of far-reaching effect. So maybe we are in agreement…? It also seems logical that your system would make all manner of (chronic) adjustments in its vital functions to reduce that threat accordingly.

That is not to say that I believe neuroinflammation to be the root cause of all POTS, just that theoretically it could be a contributing factor, in some cases.

I am speaking mostly from an observational standpoint – having watched the relationship between heart rate, migraine/cluster headaches (which certainly feel like inter-cranial inflammation/swelling/pressure is involved), body temperature, breath rate, periods of both orthostatic tolerance and intolerance, etc.….for many years, within my own system.

But, as I said, it was just a thought.

How the Shungu findings of decreased glutathione and increased lactate fit in there (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22281935). He noted they could be caused by “increased oxidative stress, cerebral hypoperfusion and/or secondary mitochondrial dysfunction”. There indicative of perhaps hypoxia but not necessarily neuroinflammation?

Would increased oxidative stress result in increased inflammation?

Cort,

Consider the known problem of pressure ulcers in people who are confined to bed. Reduced blood flow to areas causes erosion of tissue and inflammation. Bacteria can then be secondary invaders, and hard to eradicate. So, oxidative stress in the connective tissues absolutely causes inflammation. Why wouldn’t this be true in the CNS ?

Thanks for the insight Merida. It makes sense to me 🙂

Not the classical type of inflammation, I agree.. So, what type is it? I have long been puzzled by the idea of an hypoperfused yet inflammed brain…If blood lacks, what is the inflammation made of? “Phenomenologically”, I seem to experience both! When I must lie down, now, I feel heat – the “flame” of inflammation I suppose – in my head, and also, I feel like I need to allow some blood to make it up there. I find puzzling both my self-experience and the theory that would explain it…

Martha”it makes me wonder if the POTS (and fast heart rate) that so many of us experience could primarily be a compensatory method to assure that enough blood gets pushed into an inflamed brain (and/or blood vessels). It seems like this would be an essential life-saving mechanism.”

This is the 1 million dollar question for me also, i agree with you. I think that there is something wrong with the vascular system, autoimmunity against adrenoceptors or a sort of sepsis.

My gut feeling as well – the vascular system!

Yes!!! And my thoughts are slightly expanded to fluid dynamics of the central nervous system.

Merida- you’ve mentioned fluid dynamics a few times, have you ever looked into craniosacral or cranial osteopathic therapy? It involves moving the cns fluids and restoring balance- I’ve had it help people with fibromyalgia. Forgive me if you are already aware. I’m just stumbling onto LDN and looking to share with patients … Great article!

AL, unfortunately, is worlds away in a lot of ways from MA and it’s just not possible to volunteer to go down there for me. If Dr. Younger could find some volunteers to conduct blood tests or similar near me I would consider being a subject. Real invasive stuff…I’m already in a lot of pain!

Those two commenters might have convinced me to give LDN a second trial, though, after a disastrous first one. I still think fibro subtypes are what complicate treatment.

Steve, I’m a MA native, born in & lived near Plymouth 45 years. Now I live in AL, about 1.5 hours north of UAB!! I got FM/CFS in MA & have been sick 23 years. I already emailed Jarred Younger and hope I can participate in his research. Will keep the forum updated.

Glad to hear it Julie!

Cort, thanks a ton for getting this info & for this article. Though a MA native, I’ve been living in N. AL 13 years. I just emailed Jarred Younger’s Lab and offered to be a participant in his research. It will be taxing, but I’m determined to help any way I can. How can I not, with UAB being just 1.5 hrs away??! I’ll keep the forum updated. Thanks again . His research is fascinating and your article is excellent.

I wonder about the connection between chemical sensitivity and the cytochrome P450 metabolic pathway. There seem to be connections between this pathway and the functioning of microglia.

I was first diagnosed with CFS in 2003 by a physician with experience in chemical sensitivities, among other things. He ordered some tests related disorders of porphyrin metabolism (within the cytochrome P450 pathway) from the Mayo clinic which came back as positive.

Just wondering.

Excellent article. A naturopath gave me Naltrexone about a year ago but I never took it seriously. Now I will. I’m wondering if Jarred Younger has considered nasal glutathione which crosses the blood brain barrier…this same naturopath..Laurie Mischley has done research on Parkinson’s and nasal glutathione…she’s been able to provide a lot of help for PD patients. Cort if you could pass this info along to him…that would be great…maybe it’s already on his list, but would probably be helpful for him to talk to Dr. Mischley. Here’s one of her papers.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23240940

“…Younger proposed one scenario – and it’s only one – which could explain the post-exertional experienced by some people. The increased blood pressure that occurs during walking or exercise is known to release endorphins. Ordinarily those endorphins should make you feel better, but if the microglia are sensitized to endorphins; i.e. if they get activated by them – those endorphins could trigger the opposite – feelings of fatigue and pain that last for several days…”

My own self-experimentation based on earlier blogs regarding “oxidative reperfusion”, proves to my satisfaction that moderate-intensity, fat-burning exercise does not produce post-exercise malaise. In fact it helps achieve an improvement in overall condition. I strongly agree with Younger’s later comment:

“…if leptin is a player then cutting down stress eating, losing body fat, exercising at a very steady and light rate and eating low glycemic and staying away from high carbohydrate diets could help a bit…”

Actually this has helped me a LOT… as I have been posting occasionally. Sorry I owe Cort a Guest Blog posting and never get time to complete it, plus I keep learning more and fine-tuning my protocol. Short version: I need very high doses of magnesium as I follow the protocol for low-carb diet and lots of fat-burning exercise. Other things I find beneficial, is doing stretches in a hot spa pool – even now after lots of improvement, I find stretches in ordinary “on the floor” conditions very hard to do. And massage from a Chinese Tai Chi or Qi Gong therapist who understands fibromyalgia – I have been very lucky to discover one by chance.

I don’t know how relevant my experience is for CFS sufferers.

I’m sure it’s relevant to some people! We have a big group with a lot of different kinds of MECFS and FM sufferers. I can’t believe it may not be relevant to people with FM as well.

I have the darnedest time with stretches. My muscles are so darn tight and they respond very slowly to stretching…It’s been another of the oddities of ME/CFS for me. …Oddly enough I often pull my back out doing leg stretches…

Think about pelvis and sacrum and functionally short leg – usually on the left side. Often connected to a mild scoliosis. However, anything that stretches the sacral ligaments can tilt / rotate the sacrum and cause the pelvis to be higher on one side. The neck is absolutely affected once the pelvis changes – especially the critical atlas/ axis relationship.

Help! Am I the only one thinking about this structure / function angle?

yes yes yes; i had to have both hips replaced 2 years ago; since then i have had so much neck and back pain; the surgeon told me i ended up with both legs slightly longer; i had always had one leg slightly shorter than the other since a child

Re: the debilitating stiffness of muscles with FM. Prior to getting this illness, I was very athletic and did a lot of activities that involved training. When one is training, one experiences an increase in stamina, an increase in strength, and an increase in flexibility. It’s a new, foriegn, and frustrating experience to stretch, do some exercise, do physical exertion on a daily basis and have the OPPOSITE happen! So, it took 22 years–yeah, I was THAT stubborn- (but there were many other complicated factors involved I couldn’t control)–to finally downscale my life so that I’m not over-exerting myself as often. But a lot of damage was done, and I don’t know if I will gain any strength, stamina, or decrease in pain as a result of this downsize.

Yes, that is what I am saying about stretches – only doing them in a hot spa, has been a pleasant experience and still is. Even now that I have almost normal flexibility back again after 2 years of my informal protocol, stretches still “feel nasty” on terra firma. Everything is different in the spa. The muscles are warmed, and my body weight is supported by the water. I can pretty much relax everything, go semi-floating even, and concentrate on stretching the muscle I want to stretch without throwing added stress onto other muscles due to the necessary posture which happens with most stretches on terra firma. In the spa I can actually feel the muscle yield nicely and stretch. But on terra firma, the muscle feels like it wants to turn into concrete in protest at my attempts to stretch it!

I too was very athletic and limber before CFS. At the time I became ill I was exercising for nearly 1 ½ hours a day. A combination of stretching /jogging /yoga and targeted strength training. Over time I have given up nearly everything. Late 2013 into 2014 I finally gave up even walking on the treadmill. The one thing I have kept was my morning stretches. I have done nearly the same 15 to 20 minute stretching routine for years. In 2013 I noticed that no matter how much I stretched, I was only getting LESS LIMBER! Where I notice it the most is my Achilles tendons. At times it just feels they are going to pop. Like a rubber band that has become hard and brittle, with no give. At times I feel this tightness even when I am not stretching.

Excellent blog and interview Cort. I think you are very privileged to have someone like Dr Younger working in the USA and hope everyone who is able will support his work. He’s one of the most promising researchers we have.

I see Younger as a new breed of researcher of whom hopefully we’ll have many more. Someone who didn’t get stopped by the prejudices of the old school. Someone who choose this field early and grew up in it and is being successful in it. That’s what we’re looking for!

I hope he continues to be successful and others see FM and ME/CFS as a good career path – as a place they can really make a difference. This is a place to make your mark and make a profound difference.

Look what Younger did with LDN…Who was using LDN for FM or ME/CFS before he studied it? Very few people. Those studies alone have helped so many people. Where else can you do that? Not many places.

We have to give big kudo’s to the University of Alabama at Birmingham for providing this opportunity.

Cort -yes, yes, yes!

It’s the microglia, right 🙂

I sincerely hope so for two reasons:

A) there is an enormous amount of research being done on them. Over the next couple of years as the techniques for measuring them become mainstream we’ll know if it applies to ME/CFS and FM. If it does I imagine the evidence will be incontrovertible. ME/FS and FM get legitimized right there.

B) Lots of work is being done to find treatments and we should be able to hook into that as well.

Being part of a growth field would be a good thing! I hope it works out!

Agree. Finding biological evidence is of paramount importance.

no no no it’s the stealth-virii INSIDE them 😉

I hope everybody noticed the link to the videos that we can all rate online to help Dr Younger choose a suitable one for upcoming studies:

https://uab.co1.qualtrics.com/jfe/form/SV_0vNM8AOd9FJsnPf

I just did the rating task and it’s fun and interesting. I recommend it!

So rare that we can help with serious biomedical research from our sofas!

Let’s get stuck in!

Thanks Sasha. I’m looking forward to watching them.

I was unable to access the videos. I had a no plug-in available notice. It may be because I was using a mobile device. It may be because they had all the feedback they needed. Anyway, they emailed me and I filled out the questionnaire to be a participant since I live only 1 and 1/2 hours away. So we’ll see what happens.

Hi John Whiting or Cort,

Can you clarify – do you mean ferritin levels will rise or fall with tnf alpa. Are you saying they are correlated and if so which way? Ie with low ferritin you’d expect what etc.

Also, I found minocycline helped enormously when I was given it I think for something pelvic. It honestly helped my head but more than that I had energy and clarity of thought. Dr Ros Vallings would not keep me on it because of the dangers of long term antibiotics, but this was years ago. What are your thoughts on long term antibiotics. I’ve had trouble getting any dr to believe me. I also went into remission following emergency surgery for a ruptured appendix. Was it the anaesthetic, or the antibiotic cocktail. I’m sure flagyl helped? That was always peter snows thoughts.

My latest ‘stumbled’ upon med to help has been voltaren slow release 75 mg. it does nothing at low dose, but at this high dose it helps. I can still go past my limits and crash, but I ‘feel’ better when I’m good. The other thing to have helped is LDN- it was the first thing to provide more resilience . A local go has been using it here in NZ for over 10 years. I’ve been taking it about 6 years. He will give a patient in the pain of fibro/ ME and if the injection relieves globally he gives at 4.5mg.

With about three million CFS/ME sufferers and nine million who have FM, that’s a lot of people who have cut way back on their drinking. Is the liquor lobby aware of this? Perhaps they would like to make a contribution to the research.

I have problems with drinking and have for years. I feel a tightness in the back of my neck and just generally feel bad most of the time.

Every once in a while I can have a drink without feeling awful afterwards and I really wish I could enjoy a drink now and then.

I was pleased to see it mentioned in this article. I wasn’t always like this

Check out this research about plants and Microglial inhibition

http://www.mdpi.com/1420-3049/16/2/1021

Wow, that is interesting:

“…Microglial cells play a dual role in the central nervous system as they have both neurotoxic AND neuroprotective effects…”

So getting the balance right would be very important.

I think the microglia gets activated because the brain doesn’t get enuff blood and oxygen. The microglia kicks in to proctect the healthy tissue by ‘eating’ the damaged one. If true, blocking the microglia is a very bad thing.

This sounds highly plausible to me. I have often suggested that tight myofascia as well as muscle tension, may inhibit blood flow and oxygen flow, especially in certain postures. Among the symptoms of my Fibro for a long time, are POTS type symptoms; my heart gets overloaded quickly and easily in some quite innocuous postures. It makes sense that the brain may end up oxygen-deprived as well.

Maybe the post-exertion malaise is especially bad for certain types of limb muscle movement too, for the same reason. I was a dedicated cyclist when I went down with fibro, and the pain in the leg muscles was one thing, but the neck and shoulders and arms and torso were even worse even though they were not being actually exerted like the legs.

I have experienced major improvement over the last 2 years with the basic informal protocol I described in an earlier comment. The Chinese massage therapist I go to, when I said “so much improvement in the last 2 years, I am very grateful”, he replied, “1 more year, maybe you all better”. That is probably fair comment on my current improvement trajectory. But I do not believe it is a “cure” I am undergoing, I think I probably need to live the way I am living, for life, or symptoms will return.

“- it makes me wonder if the POTS (and fast heart rate) that so many of us experience could primarily be a compensatory method to assure that enough blood gets pushed into an inflamed brain (and/or blood vessels). ”

“That is not to say that I believe neuroinflammation to be the root cause of all POTS, just that theoretically it could be a contributing factor, in some cases.”

“Also, the POTS was one of the very first patterns to disappear once I started taking LDN.”

**************************

I was just thinking about some of the comments made by Martha Lauren and how LDN made her POTS symptoms disappear. I also experienced POTS (and a fast heart rate). My POTS symptoms disappeared also, by raising by dopamine levels with tyrosine, taking an anti-inflammatory and taking antihistamines. My blood pressure went up, and my heart rate went down and my ME/CFS symptoms diminished substantially. I wonder if the POTS in Martha’s case disappeared because of LDN’s effect on stabilizing dopamine and endorphin levels? Is the neuroinflammation a direct result of low dopamine/endorphin levels causing prolactin levels to rise? Does restoring these brain chemicals dampen inflammation by reducing prolactin?

Prolactin, an immunostimulating peptide hormone, is linked with a number of autoimmune diseases. Diminished dopamine levels in the brain cause prolactin levels to rise. Prolactin stimulates autoimmune disease, and this stimulation is determined by genetics. Prolactin is a growth factor for lymphocytes with the potential to stimulate immune responses at many levels. Prolactin is a cytokine.

I was just wondering which came first; is it neuroinflammation that is causing POTS, or is it POTS that is causing neuroinflammation because dopamine/endorphin levels are biophysically low causing immune stimulating prolactin to be high?

Andrew Miller’s work suggests reduced dopamine levels could be crucial in ME/CFS. It suggests that the body overreacts to inflammation in the presence of low dopamine levels in the basal ganglia.

Hi Rachel,

I agree – many possibilities, including dopamine’s affect on the immune system. I fact, that is primarily why I began (hesitantly) taking LDN: to calm my immune system which appears to have been stuck in an auto-immune or hyper-immune response. And, indeed, that was the other major (and most obvious) pattern that calmed down on the LDN – I stopped having major sinus congestion, sneezing, and sinus/migraine headaches by the end of every day. (For me, this effect began at a dose as low as .5mg.)

So, I see many possibilities, and many inter-related possibilities. I just know that I also experienced a pretty immediate shift out of the POTS right at the same time. Suddenly I could take a walk like a normal person, and my brain didn’t feel like it wasn’t getting enough oxygen, and my heart rate stayed much lower. And it has pretty much stayed that way.

That could be because it calmed some autoimmunity against against adrenoceptors (which control the diameter of blood vessels), as Gijs suggested…..or, that the LDN dampened the activity of the microglia, and therefore my entire immune system sensitivity/reactivity….and, therefore, inflammatory response…..

….I don’t know. I’m going to stop talking about it for fear of jinxing it!

Martha

i wonder when i am going thru what i can only describe as an intense flu like pain in entire body for several hours; is that when I am in a bad inflammatory period? and the comment about that the microglia can be provoked with certain factors and then unprovoked with certain factors certainly explains why some periods within the same day, i can feel somewhat normal and then within a few hours go into bad pain and when the bad pain comes on is when i want to go to sleep and lay down; i always thought it was my daily dosage of cymbalta wearing off so here it -the pain-coming again in full force

Hi, all! I have been on LDN for a year and 3 months, and am doing quite well on it . However it was a bumpy start. Getting the dose right for a particular individual can be challenging. Some folks here mentioned taking antibiotics or antivirals to calm microglia down, but there are other drugs already available that can do that. Consider discussing the drug Seroquel with your doctor. Now, I’m not talking about high doses they use as an antipsychotic. Seroquel is often used off-label for insomnia. I suffered terribly from insomnia for many years, and the only thing that seemed to help at all was Ambien CR 12 mg. It made me sleep walk, sleep eat, and I still woke up feeling like I didn’t sleep deeply enough. So my doctor was going to send me to a sleep specialist. In the meantime, he stopped the Ambien and put me on Seroquel 50 to 100 mg at bedtime. For the first few days it didn’t seem to help at all, but then it started working great! I very seldom have a sleepless night now. If you have sleep issues, you might consider trying this. Do your research on this drug, though. It calms down microglia, but can also cause problems with blood sugar and weight gain. So far this has not been a problem for me, but then, comparatively speaking, I am on a low dose. I’m feeling better now than I have in a long time, knock on wood.

If you’re on Seroquol, have your eyes checked frequently. None of the doctors I knew where aware they can cause cataracts. I might have gotten them anyway, but they appeared on both eyes after fairly long term use of Seroquol for insomnia.

So this research could fit nicely with Richie Shoemaker’s testing on Chronic Infflammatory Response Syndrome?

Cort, I found this article on narcolepsy VERY interesting. Discusses a hit and run autoimmune theory.

I couldn’t help but see potential parallels with CFS:

http://www.prohealth.com/library/showarticle.cfm?libid=20749

Oh I am so interested in this study ! I have suffered with FIBRO/CFS for years. I have seen numerous doctor’s. I also have been diagnosed with Polymyositis. The pain is excruciating at times. Every day is a struggle. I would be all for a brain scan.

Thank you for all the work you are doing to try to help all of us who suffer from this life sucking disease.

I would love to be one of the studies that he tests on. With my fibromyalgia and neurological condition not getting any better i would love to have some relief.

Hi, Heidi, Unfortunately, Dr. Young is not an M.D.doing experimental treatment. He has a research grant and is gathering bio data. But his work may discover a measurable physiological condition that detects neuroinflammation and links to ME/CFS.

I live in the Boston area and see various doctors for different problems; most related to CFS.

I read with amazement when so many contributing speak of taking LDN. I do not know anyone here who will prescribe it.

Something that I don’t understand is that Younger says endorphins might make it worst. But one of LDN’s mechanism is that after a temporary blockage of opioid receptors there is a release of endorphins and enkephalins that are beneficial to the immune system. Kind of contradictory don’t you think?

I was hospitalized as a child with encephalitis caused from complications from the mumps. I remained in a coma for several days. This was in the early sixties before the mmr vaccine. I was diagnosed with FMS in the early nineties and was wondering if any studies have been done on chronic brain inflammation caused by a viral infection. The only treatment that has worked to reduce my pain is low doses of hydrocodone (250 mg a day) but my doctor will no longer prescribe it for me because of the new classification. I am miserable, flu like, even though I walk two miles every morning. I feel good initially then after my walk I feel like my head and body are throbbing.

Your study sounds very promising.

I missed the zoom call this morning, but have read about your research. I developed Fibromyalgia and CFIDS in 1989, age 45. Around three years ago, I started using a pill of 2MG Naltrexone. With that, all Fibro pains were gone and are gone today. Also I had the DFIDS in check until 3 months ago. Nothing seems to work to make it go away.

I have a pressing headache, mind fog, great fatigue, IBS and stomach growls.

Could you take my health record and possibly see how I can get back in my life. My present circumstances seem to match your research.

Hi Jo, unfortunately there’s no way to get ahold of Jarred through this website. Because he’s a researcher not a doctor he would probably not be able to suggest anything. We’ll continue to follow his work, though, which does include some clinical trials.

What botanical anti-inflammatory supplements work best?