Immunologists aren’t interested. Neurologists, in general, are to be avoided. Endocrinologists can’t be bothered. Except for primary care physicians specializing in chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS), the outlook in the medical field for ME/CFS patients is pretty bleak. If a chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS) patient doesn’t encounter hostility, they’ll most likely get a blank look at the doctor’s office and a prescription for an anti-depressant.

Todd Davenport, Staci Stevens and the exercise physiologists at Workwell (formerly Pacific Fatigue Lab) well know about the futility of getting University departments interested in ME/CFS. There is one bright spot in the otherwise rather dark academic universe, however. One specialty – physical therapy (PT) – is beginning to prove the surprising exception to the rule. Not only are the physical therapists (PT’s) Workwell is working with interested in chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS), but they’re fully embracing the science behind it.

Why is physical therapy becoming the first medical specialty to “get” ME/CFS? Perhaps because PT’s are so hands on – they’re not caught up in some theoretical dialogue about their patients – they’re focused on the here and now and what they can do to make their patient’s lives better.

During a recent telephone conversation, Todd Davenport, the physical therapist associated with the Workwell Group, noted that the physical therapy field is actually VERY interested in chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS)! He’s presented talks on ME/CFS to three symposiums attended by approximately 10,000 physical therapists.

This is the first of a series of blogs on the Workwell group, a small group of exercise physiologists in California whose exercise testing, disability evaluations, exercise prescriptions, and their ability to penetrate the PT field have made a profound difference in chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS) over time.

The Physical Therapist and ME/CFS

“I am a physical therapist and movement is my medicine.” Todd Davenport

The story started in the spring of 2008 when the chair of the physical therapy department at the University of the Pacific, a private university in Stockton, California, was cruising the UOP’s website when he came on something called “The Pacific Fatigue Lab”.

Davenport, who apparently loves to collect titles, (he’s a physical therapist (PT), Doctor of Physical Therapy (DPT), has a Master’s in Public Health (MPH) and is a certified Orthopedic Clinical Specialist (OCS)) was intrigued by the fatigue part. Davenport’s Master’s thesis was on inflammatory muscle disease (IMD) – a fatigue and muscle weakness disorder. While ME/CFS and IMD are different, during a telephone conversation, Davenport noted that the approach to them is similar.

A physical therapist’s first goal in inflammatory muscle disease is to eliminate, using rest and pharmacological drugs, any flares a patient is experiencing. Once the flare is over, the PT tries to expand the person’s functionality without overloading their system. Their protocols are symptom limited: if the exercise produces a symptom flare, the physical therapist reduces it.

That’s remarkably similar to the way Staci Stevens, an exercise physiologist who has chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS) and uses exercise testing to prove disability in ME/CFS, approaches the disease with her clients. The only real difference between her approach to ME/CFS and Davenport’s approach to inflammatory muscle disease (IMD) is that IMD has pharmacological drugs PT’s can use to reduce flares, and ME/CFS does not.

After hitting her head against the wall so many times with different academicians, Staci Stevens said she was shocked to come across a physical therapist whose management approach was almost identical to hers. Davenport, however, was simply following a basic tenet of physical therapy: never impose a physical load on a system that can’t handle it. He believes the best results come from listening closely to the patient:

“The best practice with this patient population, as with all patients we see as PTs, comes back to good, old-fashioned listening—taking on good faith what the patient has to say, and going on from there.” Davenport

Davenport is also listening closely to the science. If the research indicates the aerobic energy production system is broken in chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS), far be it for him to assume otherwise. Davenport has lead the way in helping the PT community understand this puzzling disease.

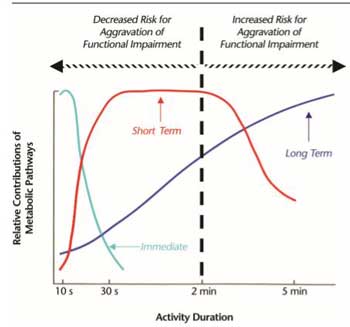

In their landmark 2010 physical therapy paper, “Conceptual Model for Physical Therapist Management of Chronic Fatigue Syndrome/Myalgic Encephalomyelitis”, Davenport and the Workwell Group (Stevens, VanNess, Snell and Little) concluded that, “The metabolic impairments observed in people with CFS/ ME suggest the need to limit the intensity of activity to avoid excessive use of the aerobic energy system”. They asserted that heart-rate biofeedback could be effectively used to identify activities which did not produce harm and recommended that exercises in general last less than two minutes in order to avoid overstressing an overburdened energy production system.

Do No Harm

When seeing an ME/CFS patient, Davenport typically begins with mild stretching to increase the patient’s range of motion, and interestingly enough, increase their energy availability. It turns out that the impaired range of motion commonly found in ME/CFS results in reduced “mechanical efficiency”; i.e. increased energy is needed to move one’s limbs. When you’re as energy-depleted as ME/CFS patients are, that reduced range of motion could obviously constitute a rather significant energy drain. Plus, because that joint and muscle friction causes pain, which activates the sympathetic nervous system, reducing pain can help quiet that system down as well.

Davenport combines stretching exercises with deep diaphragmatic breathing exercises in order to increase oxygenation and energy availability. When the patient system has rehabilitated a little bit, he adds very short-term, low-load, strengthening exercises.

Pacing is another essential part of Davenport’s approach. A “push-crash” pattern in which people reach peak levels of activity only to fall into a crash is common. Lopping off those activity peaks and filling in those crash-induced valleys by pacing is essential to removing stress on the system and allowing it to rehabilitate to the extent that it can.

Davenport has no illusions about how difficult pacing can be. Coming to grips with what you can really do physiologically is not easy. One of the greatest difficulties Staci Stevens has with many of her disability clients is convincing them how little activity the exercise tests indicate they should be doing.

(The very severely ill, unfortunately, rarely make it to his and other physical therapists’ offices, but Davenport holds out hope for teleconferencing visits at some point. The problem with that venue is getting health insurers to pay for it.)

When a Physical Therapist Gets ME/CFS

Nicole Rabanal didn’t need to learn about ME/CFS to understand how to pace herself. A physical therapist who stated she woke up one day “feeling, out of the blue, like I’d been hit by a truck”, Rabanal had an array of ME/CFS symptoms (severe flu-like symptoms, eye pain, headache, ‘heavy’ head, muscle weakness, random numbness and tingling, difficulty breathing and swallowing.”) As most patients have, Rabanal did the specialist circuit – seeing 17 of them – before finally realizing she had ME/CFS.

Rabanal now employs her physical therapy protocols on herself. Making sure not to overload her body, she works a two-hour shift in the morning, then lies down, taking oxygen with ice on her head for 4 hours, then works for two more hours. She goes to bed no later than 8pm, and does nothing on the weekends. She can’t stand unsupported for more than five minutes, and has to limit her socializing because of the energy drain. She uses a Fitbit to monitor her heart rate.

In a feature article, “The Real Story About Chronic Fatigue Syndrome”, on PT in motion, Rabanal, who is associated with Dr. Bateman at the Bateman-Horne Center, in Salt Lake City, talked about how important her physical therapy training had been to managing her ME/CFS.

“The knowledge and experience of having been a PT for nearly 25 years has been incredibly helpful to my personal treatment plan. Listening for and understanding the signs of when I’m pushing beyond my energy limitations, then implementing appropriate exercise and stretching, is a big part of the management puzzle. This of course is what PTs do every day with patients, in one form or another—we listen closely and apply our knowledge to their presentation and what we learn from them.” Rabanal

Rational for Workwell’s and Davenport’s Two Minute Exercise Protocol: Three types of energy are present to our muscles. The Light Blue-line represents short-term energy stores in our muscles which lasts for about two minutes and produces no harmful effects. The Red Line – represents anaerobic energy production which after a few minutes produces symptoms. The Dark Blue Line represents a broken aerobic energy production system which quickly poops out causing symptoms. Davenport and Workwell use the two minutes of energy storage (light blue line) as the basis for the duration of their exercise/activity regimens in ME/CFS

Davenport asserted that because most ME/CFS patients PT’s come across have not been diagnosed with chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS), PT’s must be on the alert for the typical signs of ME/CFS such as post-exertional malaise, and fatigue that does not significantly improve with rest. PT’s, he warned, have to be flexible. They are hardwired to have their patients exercise and usually that works. But when it doesn’t, instead of labeling them “non-compliant”, they should consider they may be dealing with a person with ME/CFS.

“Pushing graded exercise and telling patients that they just need to get up and get moving”, Davenport says, is a mistake. Over time, he very slowly builds on those anaerobic exercises – not to fix the aerobic system (it’s broken after all) – but to strengthen anaerobic functioning.

Rabana agrees and warned that unless PT’s know the diagnostic criteria for ME/CFS, they run the risk of harming their patients.

“Because if we aren’t correctly identifying this patient population, it’s easy to push patients into a treatment or exercise program that will make their condition worse. They are likelier to be noncompliant, disinclined to follow up with care, and present as a returning patient whose condition never seems to improve.” Rabana

That doesn’t mean that exercise can’t help. Quite the contrary – it can be very helpful when done correctly – and Davenport and the Workwell Group have a case report to prove that.

A Science-Based Approach to Exercise in ME/CFS: A Case Study

A case report published in a 2010 IACFS/ME Bulletin demonstrated in dramatic fashion how helpful a science-based approach to exercise can be in ME/CFS. It involved a 28 year old ME/CFS patient who was concerned with her increasing inability to engage in anything but the most rudimentary activities. Employing a push-crash approach, she would get things done when she felt better but then would be beset by whole body fatigue and pain. With her “good” periods rapidly disappearing, she feared for her ability to do even minimal activities.

Her oxygen consumption on a single exercise test was in the low normal range, but other measures (peak exercise systolic blood pressure (112/72), respiratory rate (38 breaths/min), and ventilation (73 L/min) were out of range. Blood pressure maintenance was clearly a problem, as it dropped upon standing and failed to reach resting levels during exercise. (It should go up during exercise. It should be noted that people with ME/CFS display a wide variety of abnormalities on exercise – some have low oxygen consumption; others exhibit problems with ventilation, or heart rate or blood pressure, etc. The common denominator seems to be some sort of cardiovascular problem that shows up during exercise. Look forward to an upcoming paper by Dr. Betsy Keller on that.)

Like many people with ME/CFS, the patient felt fine during the exercise; in fact, she reported that she felt “great and energetic” for about six hours – and but then she declined and felt worse the second and third days.

Doing exercise that minimally engaged her aerobic energy production pathways allowed one person with ME/CFS to increase her functionality

For the next year, she followed Staci Stevens’ activity and exercise program religiously. Using a heart rate monitor to ensure that she operated in her anaerobic “safe-zone”, she paced, did diaphragmatic breathing, upper body flexibility stretches, and resistance and short-term endurance exercises three times a week. When her heart rate monitor indicated she was out of her safe zone, she sat or lay down. She kept an exercise log throughout.

A follow-up a year later indicated that not only had she stopped her activity regression, but she had been able to increase her activity levels without causing ill effects. Despite the fact that she had been only engaging in anaerobic activity, her CPET tests revealed significant improvements in virtually every category ((Peak VO2 (26.1 ml/kg/min), ventilation (90 L/min), respiratory rate (54 breaths/min), heart rate (189 beats/min), and systolic blood pressure (170/98)).

This person still has a mysterious problem with aerobic functioning. She’s not out at the gym pumping weights or running or anything close to that. Her aerobic energy-producing system is still busted, but she is much more functional and she feels much better and her test results reflected that. In the case report, Stevens and Davenport proposed that their protocol had increased this patient’s ability to engage in submaximal exercise. In layman’s terms, that means she’s able to do the household chores and other activities she was unable to do before without relapsing.

Seven years ago, Stevens and Davenport ended their case report stating that further study was needed.

“These observations regarding potential improvements in cardiovascular and pulmonary system impairments require additional replication in the context of controlled intervention studies.”

Seven years later, at least three large CBT/graded exercise studies costing millions of dollars (PACE, FIT, GETSET) have been published which had minimal at best results. Despite the fact that each was purportedly designed to increase fitness and activity levels, none employed physiological testing or even measured activity levels.

Meanwhile, the Stevens/Davenport case study – which showed actual physiological improvements using a heart-rate based activity approach – has languished in an IACFS/ME Bulletin. Staci Stevens said she would love to do a clinical trial, but Davenport noted there is little funding for rehab studies in general.

GETSET (Don’t Go)

In “Another ‘False Start’ in ME/CFS“, Davenport assessed the most recent of those trials, the GETSET trial, published in, where else, Lancet, which managed to embarrass itself again with yet another poor ME/CFS study. Calling GETSET PACE-Lite, Davenport noted that post-exertional malaise was not required to enter the trial, and only 42% of the participants completed the trial. While the results were statistically significant, the outcomes were not clinically significant (Davenport called them “decimal-dust”) and probably made little if any real difference in the participants’ lives. If you appreciate good writing and want to learn how not to do an activity trial, check out Davenport’s piece on Workwell’s website here.

Check out Health Rising’s Take on GETSET below

Spreading the Word

Workwell and Davenport want to spread the word on ME/CFS. Their data on the aerobic energy production problems and the exercise restrictions it causes has the potential to rock conference goers’ worlds. What they don’t have is the minimal funding needed to present their data at conferences. This is what happens when you’re on the wrong side of government funding. The UK and the Netherlands have poured millions of dollars into CBT/GET trials; the U.S. hasn’t spent a dime on studying the kind of rehabilitation Workwell and Davenport are proposing.

That means Workwell has to work off its own dime. With admission and submission fees (yes, it costs to present something in a conference), travel and hotel, costs typically run from $1600-$1800 per person to present something at a conference. That means a lot less outreach than we’d like from this group.

Conclusion

Physical therapy isn’t a panacea for ME/CFS and PT’s don’t present it as such. ME/CFS will still be there after the physical therapy is done, but it can relieve their pain and increase their functionality. One PT in “The Real Chronic Fatigue Syndrome” article celebrated a former kayaker’s success of paddling her first tenth of a mile after ten years of no kayaking at all. Another ME/CFS patient who could only walk 50 feet, “if that”, was able to walk for ten minutes. For those in pain, it’s possible to lower pain levels from a 6 or a 7 to a 3 or a 4. That’s a major reduction in pain. Being able to walk ten minutes is piddling stuff for a healthy person, but a major improvement for many people with ME/CFS.

I would like to share this but the ending is very awkward and implies that we as ME/CFS patients are decondition and that just continues to pass on damaging info.

?????”That’s the difference between a deconditioned person, and all the problems thafitness and quality of life.”

That last sentence got butchered but I don’t think we should be afraid of confronting the fact that because many people have very low activity levels means that deconditioning is necessarily present in some people with ME/CFS. Check out a frank talk below on this subject by Dr. Klimas

https://www.healthrising.org/blog/2013/01/23/chronic-fatigue-syndrome-mecfs-deconditioning-exercise-and-recovery-the-klimas-cdc-talk/

None of the exercise studies that I know of suggest that deconditioning is the cause of ME/CFS. Check out a blog on work by David Systrom which found that ME/CFS and similar patients display opposite readings to people who are deconditioned.

“The study also indicated that neither deconditioning or a reduced maximal effort – both of which have been suspected in ME/CFS – play a role in the exercise intolerance found. In fact, deconditioned people, ironically, exhibit an opposite finding (increased as opposed to decreased filling pressures) to that found in this study.

Not only was deconditioning not the cause of exercise intolerance but the tests results were opposite to those found in deconditioning”

https://www.healthrising.org/blog/2016/07/04/exercise-intolerance-fibromyalgia-chronic-fatigue-pots-explained/

Cort, this is a MUST WATCH, from CMRC Conference 2017 day 1 – Dr Linda van Campen. The conclusion is stunning! I don’t want to spoil it for you, but she concludes that the Cerebral Blood Decline seen in patients is entirely due to the presence of disease and NOT to decondtioning. All the data points to that. Enjoy!

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OjYKZZvlJJc&t=2s

This is the talk that precedes it, if you’re interested:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IWRA23D_MUg&t=2s

(Please bear with the Dutch accents!)

Thank you Lidia! I hadn’t heard of this until then. Sounds exciting…:)

I believe in Staci Stephens and the Workwell foundation studies. I am currently bed bound due to pushing myself to hard for unavoidable reasons. But after I got tested in 2009 @ Workwell (then Pacific Fatigue Lab), I employed both lowering my resting pulse rate, while staying within my Heart Rate guidelines. I did not get back to anywhere to a normal person, but I could at times socialize, go for short walks, etc. This is not the same as all the bogus PACE trial studies. This is sound science. Congrats to the PT and Workwell.

It’s interesting to me that our grandparents generation (pre baby boomers) didn’t exercise…. smoked drank and were not obsessed by health (l am British) didn’t get ME/CFS or maybe people did and we just didn’t know …… l have accepted that l have the genetic predisposition for developing these types of illness and am not holding my (deep:) breath for a cure …. yes l am jaded and cynical but also realistic about my chances of improving…. l loved discovering l had a homozygous 0401-3-53 genotype…. it was Ann aha moment ….. there’s an attempt to play down these genotypes lately as people tend to believe that having this genetic pattern means doom and gloom…… well for me it was the opposite…..to know you have this particular rare dbl allele let’s me relax into an acceptance….. death ? could be the real cure …… l for one have been to hell and found help only in restriction and avoidance ….. BUT l have amazing intuition and try lying to me lol ….. l suppose these are the possibly positive traits of being hypersensitive….. although the “knowing” still makes me question how the hell fo l know these things and why do l have to be so limited to experience them….. l think l may have gone a bit off topic here …… but if deep breathing and range of motion help …. go for it …….

Steve

This is too much like going backwards, that exercise–though modified– is still the answer. Obviously, obviously, if a little bit too much exercise is resulting in crashes and increased pain and immobility, then exercise is not the answer! We need to find the CAUSE of the illness and medications which treat the real problem.

I think this is just another group of clinicians who wish to add to their client base by saying they’ll be very gentle with ME/CFS patients.

I’ve tried many different types and levels of exercise over the past 24 years. At times, once a little bit loosened up, I might feel okay for 20 or 30 minutes. But the instant I stopped moving, my entire body turns into solid crushing painful concrete. There is no gain, no relief, no progress, just worsening of symptoms. Now I’m in bed from 14 to 22 hours a day. Let’s go back to the research! Let’s stop spending our money on people who are not invested in or qualified to discover the real causes.

20 to 30 mins is far too much exertion. The article was talking as little as 2 minutes and also checking heart rate and blood pressure. Not exercising when these levels are out of the patients norm. It also never said it was the answer, it said it helped relieve some symptoms, and increase the amount one can do. Deconditioning does need addressed with ME/CFS as we may eventually end up having a stroke or cardiovascular complications. 2min of light movement, deep breathing may help us avoid deconditing further.

Today for Instance I’m coming out of a crash so wouldn’t do it today. But in a couple days I will. I think we need to carefully monitor our heart rate as a vital way of avoiding the crash.

People need to read the article thoroughly to get what is being talked about here.

Ditto to your comment. I thought the article was quite clear.

This blog certainly did not mean to suggest that exercise is “the answer” for ME/CFS and if you can find a place in the blog that suggests that please let me know and I will fix it. As someone who used to be quite athletic and who’s had ME/CFS for decades I can assure you that I know from bitter experience that exercise is NOT the answer.

If you read the case study again I think you’ll see that very limited amounts of exercise, plus breathing exercises, stretching and the like can be helpful in increasing some people’s functionality. It will not, however, repair a broken energy production system.

I think everyone agrees, including Staci Stevens, who created the two-day exercise testing and has ME/CFS herself, that what we REALLY want is the answer! Until then maybe some of us can have a bit better health and more functionality with programs like this.

@Julie Yes agree. The point is that exercise is great for healthy people, and it is necessary for ME sufferers. However, in the latter population it comes at cost. We all individually need to conduct our own personal cost-benefit process. Benefits are reduced risks of preventable disease (NOT improvements of ME). Costs are PEM, relapse, feeling crap. It’s quite simple – didn’t need this lengthy obfuscating article to say this.

I disagree that it’s simple. An exercise/activity regimen based on physiological measurements done during an exercise test is not simple, and is probably done only in a handful of diseases. The fact that exercise testing shows distinct physiological impairments not seen in other diseases and a medical specialty is beginning to embrace these core findings in ME/CFS I think is quite noteworthy.

Using a heart rate monitor to determine when to stop an activity is basic but not many people do it. I’ll bet that most of us don’t do breathing exercises, stretches to reduce muscle constriction and pain and low duration exercises. Nobody is saying that this is going to cure ME/CFS but what is? This is an aid to help people feel and function better while researchers search for the answer.

The fact that one person who was apparently going downhill fast and feared she would soon not be able to do even basic household chores was able to turn that around, increase her functionality and her exercise test results substantially, suggests that this protocol – followed with rigor – can really help.

The Workwell Foundation researchers & clinicians are, in fact, VERY committed to helping ME patients, and have been for about 20 years. They alone are responsible, IMO, for the most groundbreaking work on the exercise/exertion problem in ME. They *proved* PEM — our cardinal, defining, disabling symptom — with *objective medical evidence”. They were the first to do this – and their work has been replicated by other published research studies.

Importantly & tellingly, their work is being built upon by other top, key researchers who now routinely include physical stressors (if not the full 2-day CPET) in their research studies. This would not have happened if not for Workwell.

As for exercise, Workwell Group do *not* recommend unsafe exercise. I know this for a fact because I did their 2-day exercise test several years ago & as part of the follow-up, Staci Stevens spoke to a physical therapist my doctor referred me to so that my PT could implement Staci’s exercise therapy program. I get many PWME’s most understandable apprehension at the idea of any exercise program, but once I had read WW’s papers & watched video presentations of theirs online, I knew they were the real deal.

Theirs is a program designed to help PWME’s regain some function in their daily lives. It did this for me until some unavoidable personal events slid me back into a relapse. However, I am working on resuming their program — *very slowly* and*very carefully* — which is the central tenet of their program.

For example, if a PWME is bedbound, they may or may not be able to do much, if anything. A Workwell/literate PT would have to assess their current function & capabilities. This type of patient’s exercise therapy program *might* involve, on a good day, and while lying down on their bed, gentle movements

with one leg for 20 seconds, followed by 3-6 times as long of total rest (1-2 minutes), then repeating with the other leg. And that could be *it* for that day.

Another tenet of the program is that the *maximim* you can do this program is every other day. And even that is based on guiding questions about how you feel that day. Then you are wearing g a heart rate initially all day to ensure you stay u der your anaerobic threshold — a heart rate *maximum* that you must stay under to avoid PEM (discovered through the 2-day CPET).

When I first wore the HR monitor, I set it off continually — it was truly an eye-opener.

Above all, they do not claim their exercise program is a cure — of course, it is not. However, who would not wish to function as well as they possibly could, even if still very disabled.

I did not have a positive experience with my physical therapist at all, chiropractor was ok, except I’ve been told to avoid chiropractors by my nuerologist, who to believe?? but I found my physical therapist to be ignorant and unhelpful,she did not listen to be but rather came up with her own “ideas” and mispoke for me in documents…I don’t think I will ever go back (personally) but I’m glad if there are some good ones out there helping our cause.

Yes, it’s a process. The information is out there in the form of the paper Davenport and Workwell wrote in 2010 and in the conference presentations they’ve been given. The danger with physical therapists, is as Davenport, I think said, their go to treatment is exercise.

Once they understand that aerobic functioning in ME/CFS is limited, however, they should be able to employ the rest of their training (i.e. don’t overload or over stress a persons systems) to help.

It would be great to get a list of ME/CFS knowledgeable PT’s.

My favorite part of this article is to avoid all neurologist. I refuse to ever go to another one again, hopefully I won’t have a stroke someday. All they do is rule out drugs and alcohol abuse and then send you to psych. I’m sure many can relate to this. But yes mild exercise can help increase oxygen such as swimming but other times it’s impossible to do believed to be an increase of lactic acid, then exercise is to be avoided.

Aww I hate hearing this. My neurologist is a sleep specialist and he’s been my most affective and creative doctor.

I’ve been to two Exercise Physiologists to assist with treatment of my FM and ME/CFS over the last 10 years. The second wasn’t too bad and did seem to have some understanding of the limitations I face, but the first had no idea, even though he said his wife had FM. He was an advocate of the graded exercise program, which I kept telling him did not work for me.

By trial and error, I worked out for myself that aerobic exercise was a killer. I got a fit band with a HR monitor and used it for about 12 months to monitor my heart rate while exercising. I do yoga, often poses I’ve modified for myself (because sometimes even stretching poses standing are too much, so I adjust them to lying down and stretching – now after reading this article, that makes sense), and create my own yoga sessions as most commercial yoga sessions put too much aerobic pressure on me.

I start with simple stretching and resting/breathing poses, then as I improve, move to gentle strengthening poses on days I feel up to them. It works well (until I get a set-back like having to do additional shifts at work – I only work part-time – or I have friends visit and do additional socialising – or I get the brilliant idea that I should study and fry my brain!).

Its about time the medical community started listening to us. I agree with Julie Gobbell that we need more research into the cause of this illness, but we also need people like these who listen and look at ways of helping us cope with the symptoms to live a better life (if you can call it a life) in the meantime. Its so nice to see someone finally listening.

I am not sure I understand, or that Cort has got it right in this article – what is impaired about the aerobic energy system in CFS and what is impaired about the anaerobic energy system? Surely you can’t have a good anaerobic system, along with a dysfunctional aerobic one?

The anaerobic energy system is the one used at high intensity, which is obviously to be avoided. I have Fibromyalgia, not CFS, but it was a massive breakthrough for me a few years ago when I realised that I needed to avoid anaerobic level of exertion.

Scientifically, I think staying below 65% of maximum heart rate works for me.

But I don’t understand what Cort and you are saying on here – you try and avoid aerobic activity? I thought it was ALL aerobic until you get intense enough that it goes anaerobic. Is there a “sub aerobic” energy metabolism?

Check out this Phil. This is really interesting – it’s from the graph on page 9 of the Conceptual Management Paper by Davenport and Workwell.

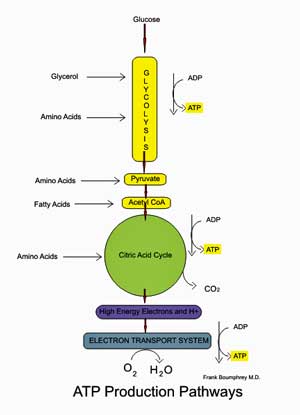

There are actually THREE systems. There is energy stored in the muscles that can be accessed anaerobically without harm for about two minutes. There is the anaerobic energy production system that starts to produce toxic elements after much more than two minutes and then there is the aerobic energy production system which is mostly broken but which starts breaking down after too long a duration of exercise in ME/CFS

I hope I got that mostly right (lol)

I believe that by limiting the period of time in which you have exhausted your aerobic energy production and thus are dependent on the more toxic anaerobic energy production process, you are doing what is suggested.

I go to a Yoga Therapist that specializes in chronic pain. she has Fibro herself so I feel safe in her hands. she takes a very small class of up to 4 people and modifies each person’s approach to the very gentle stretching exercises. If my POTS is bad that day she has me sitting on a chair or modifies the exercise so that I don’t have to deal with a lot of up and down movements.

She also taught us breathing exercises, restorative resting postures and psychic sleep- muscle relaxing Yoga Nidra.

I have been going to her for years and while it has not cured my ME, I really notice it when she is a way overseas and classes stop. Maintaining muscle and joint flexibility is crucial to maximizing my quality of life. The article resonates with me. I hope that the message gets out to PT and other exercise therapists so that they can start helping, rather than harming people with ME & Fibro

Congratulations for finding something and thanks for sharing that.

@Phil H ‘“stuck” muscle fascia’…yup, & the Fix is to find a Rolfer or an Osteopathic doc that does manual manipulation.A cleanse is like waxing your car to remove a dent. 50 yrs of ME& lots of m/bike [collapsed lungs aplenty],roofing [falls]& auto mechanic trade [pleurisy,RhArt] mishaps resulted in seized chest structures… & bam! via rolfing& osteo it’s now possible to Exhale fully.

FYI

y’all that use fitbits or wifi at home, might want to read this:

Why a Fitbit Harms More Than Helps Your Health

https://www.thehealthyhomeeconomist.com/fitbit-health-concerns/

[really ,our health sucks as it is-using wireless devices is akin to pounding a nail into a tyre that already has a slow leak.] Altho, ActiPatch, a PEMF portable mini loop device that’s price is peanuts, is sans pareil for pain attenuation in people&critters…it’s the backup tool for when the screwup threshhold has been crossed. cheers

I really acknowledge you for coming up with a gentle stretching/exercise that works. That can’t have been easy. 🙂

My solution was also to do stretches while in water – hydrotherapy pool or spa or swimming pool. Most stretches, besides the stretch itself being challenging, involve postures that put strains on other parts of the body and muscles, and this is counter-productive. Supporting the body weight in water, resolves that.

I hadn’t read this thoroughly, this particular physical therapist does indeed look good. Of Course for some to exercise even a tiny bit is unlikely. The sickest people could not make it to a physical therapy appointment, nevermind doing anything once there !and very severe cases like whitney dafoe really don’t look like they should exercise at all until their health improves.

In theory this physical therapists methods could be helpful for alot of us though, especially if we had something we could do at home(so we wouldn’t have to use precious energy getting to the appointment,etc) I think this therapist is a rarity in the field,maybe ont in california, but here in new england, i’m not seeing this happening anytime soon. I guess we can glean from some of the advice, it is so hard trying to figure this stuff out on your own though.

Yes, it is hard. We are going to do a followup blog which illustrates in detail the kinds of breathing exercises, stretches and exercises and the exercise protocols in more detail.

I do wish we had a list of ME/CFS knowledgeable PT’s.

That sounds really useful thanks Cort

Breathing exercise helped me. But it is strange i can’t breath normal with my diaphragma, it feels constant stuck and stiff like it can’t move.

Staci Stevens and Workwell and Betsy Keller have documented various problems in producing energy – one of which is problems with ventilation – or moving the lungs. I wonder if that might apply to you?

If I remember correctly, Staci reported that because the muscles moving the lungs are in constant motion they might be the first to suffer from the effects of poor energy production.

@Gijs: I had this too and still have to a lesser extend. I lacked the strength and endurance to breath deeply (but more important properly, deep ain’t the one and all answer).

Just like I can for example open one jar quite well when being out of PEM, the second gets harder and the third is a no go. With breathing the same thing happened/still happens. As one has to breath 24 hours a day, the breathing system (muscles and brain) is among the most depleted ones. Then this “light-blue line of immediate shortly available reserves” in the graph in the blog is really tiny.

I only learned to breath better since I go to a *good* PT that listens very well to what ME is and has a good intuition. I am now half a year further and my average breathing style has improved a lot; still much work to do.

One of the important aspects was that I did only a few tiny series of breathing exercises each day. They were so short that they could not have any immediate effect. They did however “let a better breathing style very slowly sink into my daily life”. Part of it likely is training/automating the brain to use a new technique, part of it likely is not making the muscles stronger but slightly more efficient.

NOTE: you *really* need to learn breathing techniques that are better for you in the long run; making any slight mistake risks that you learn yourself to overexhaust your breathing system even more!!!! Been there, done that for about one and a half year. I made, among others, the mistake to believe that breathing slower and deeper was the answer. It was not. Using less effort to breath better over the long term is (for me). That could include breathing sometimes slower and deeper but does not equal too.

Currently I do well with trying to breath no more than sufficient in the most efficient way (for both brain and muscles) as possible. I had short time (up to several weeks) improvements breathing more then required but seemed to have managed to exhaust my long term breathing resource reserves too much. One could see it this way: breathing more gave me short-to-mid term more energy, but I was going out of the “breathing envelope”.

I believe that this could be an important addition to the classic pacing protocol: next to pacing your activities over the day it is important to pace the effort you put into breathing as well. As we so easily get into breathing difficulties including getting way to early into anaerobe breathing and losing the strength to breath with the diaphragm (losing its supporting effect on blood flow and heart pre-filling), I believe we must not breath more in order to be able to sustain our efforts longer, but resize our efforts so as they fit into this “breathing envelope” I propose. I believe that doing so gives me some “spare” breathing capacity for when it *really* gets critical. Having less moments of *deep* lack of oxygen/breathing may well make PEM less deep.

I concur with dejurgen; it is not something I often mention, but it is part of my experience too, that it took months of experimentation with breathing, to get it right and happening automatically (I think it now is).

Gijs, I have experienced that inability too, I believe it is part of fibromyalgia, which I have, which is literally “stuck” muscle fascia. It is only as I got better with an overall detoxing protocol, that things started to release, including the diaphragm, pelvic and torso muscles. It was not just the diaphragm that was restricted, it was the whole rib cage as well, so I felt constantly restricted in my breathing capacity whenever I was needing more air due to exertion. I used to say to my doctor, my lungs feel like a balloon that is constrained inside a box that is much smaller than the balloon!

Thank you, Cort. TJ’s would be most welcome. We have all become aware of our limitations, and it would be great to have some instruction as to what might be possible and safe. Thank you for the wonderful work and service you do.

Occupational Therapist have successfully treated pain and chronic fatigue … read more at AOTA.org.

Ravanelli says she takes oxygen for four hours with ice on her head. Can some explain the oxygen part?

‘Using a heart rate monitor to ensure that she operated in her anaerobic “safe-zone”’

Should that read ‘aerobic’ rather than ‘anaerobic’?

This is so darn complicated. I was just told by someone that the first two minutes of exercise are doing using our anaerobic energy production system and that is the reason for limiting exercise to two minutes.

Clearly there is more to learn about this subject….

At rest we use the aerobic system, then it ramps up as intensity increases, until eventually we go anaerobic (but only if we keep ramping up the intensity). Cort, mate, if you don’t understand the basic physiology, don’t post what tries to be a learned article…?

That’s not quite correct and I admit I and we are on a learning curve here. I don’t mind that.

Actually the aerobic and anaerobic energy production systems are going on all the time; it’s the relative production of both that switches as we continue to exercise. And yes, the anaerobic energy production system kicks in more as our aerobic energy production poops out. I’ve been writing about that for years!

It turns out that there is another source of energy that I didn’t know about until, well, today. It turns out that our muscles store about two minutes worth of energy in them which can be accessed without harm. (Check out the image I just put on the blog and the graph on page 9 of the Conceptual Management Paper. That is the energy that Davenport and Workwell seek to use with their two-minute exercises.

After that the aerobic energy production system kicks in which quickly poops out leading to a reliance on anaerobic energy functioning and the toxic byproducts it produces. That is my understanding – at least for now (:))

Having said that, we can go anaerobic very quickly if we go high intensity immediately…like 100m sprint or a snatch or clean and jerk in olympic weightlifting for example.

Our muscles and liver store 90 mins approx. worth of glycogen…I once ran a 66min half marathon at 11 am off no breakfast 😉

Anaerobic means “without oxygen”. PWME’s need to stay under their Anaerobic Threshold, which can only be definitively measured with a 2-day CPET. It can be estimated, but not known for sure without the test.

Everyone has anaerobic (without oxygen) energy (a metabolic pathway) for *up to* 2 minutes after resting. Then, instead of the aerobic energy kicking in as it does with non-PWME’s, ours is broken & instead another anaerobic (without oxygen) pathway kicks in– with all of its attendent problems – lactic acid, etc and then PEM. If we can keep our heart rates below our “number”, then we can avoid PEM — crucial to us making the most of what energy we do have– without a lengthy payback.

Non-PWME’s can use their aerobic energy all day long without the costly anaerobic energy kicking in. For us, it can kick in after mere seconds or a couple of minutes.

-my layperson explanation for what is occurring…

total boloney if you have M,E not cfs then any exercise is harmful and even life threatening

The exercise program they prescribe does not look like exercise in the usual sense for, I would venture to say, most PWME’s.

I describe, above, an example of what exercise could look like for a severe PWME under their program.

I’ve noticed that the comments on this website are quite negative. From my perspective, this article is great news. A field is showing interest and tangible treatments to improve functioning. That’s awesome! However, I see “not enough” “wrong conclusions” “won’t work for me” “wrong ideas” and so forth in the comments.

I’ve been disabled with ME/CFS and POTS for seventeen years and I understand that we truly haven’t gotten enough and that things have been so bleak. But I see a huge change in the ME/CFS world. Maybe it’s time to start focusing and celebrating the positive and letting go of the negative of the past? Maybe we need to support the professionals coming into this field.

Maybe we need to celebrate and show our appreciation to people like Cort. Thank you Cort. I appreciate your work everyday. You are giving me hope to keep fighting. Keep up the good and important work!

“In their landmark 2010 physical therapy paper, “Conceptual Model for Physical Therapist Management of Chronic Fatigue Syndrome/Myalgic Encephalomyelitis”, Davenport and the Workwell Group (Stevens, VanNess, Snell and Little) concluded that “The metabolic impairments observed in people with CFS/ ME suggest the need to limit the intensity of activity to avoid excessive use of the aerobic energy system”. They asserted that heart-rate biofeedback could be effectively used to identify activities which did not produce harm and recommended that exercises in general last less than two minutes in order to avoid overstressing an overburdened energy production system.”

Limit intensity…then say that duration needs to be limited? This is basic science, language…and frankly…bollocks.

Why is limiting exercise intensity and duration bollocks? I’m confused (???)

Because if you read the quote it says to limit intensity, then it says limit the duration to less than two minutes…it DOESN’T SAY ANYTHING ABOUT LIMITING INTENSITY.

Also get them to talk about models/theories of fatigue. What I’ve read so far is very superficial and confused

I finally see what you mean….

We didn’t go into the details of the exercise protocol – that’s for another paper – but the protocol requires that you keep your heart rate under an intensity which the exercise test identifies.

There are ways to roughly identify that without using an exercise test and we will get into them in the next blog.

Speaking as a physical therapist with ME/CFS, living this disease and being a health care provider for it are two completely different things. I think we would all agree that it is a rare gift to find a provider that truly understands the implications of ME/CFS and can advocate for us in a healthy way. Physical therapist fall into this, as most other providers, due to the lack of education and understanding of ME/CFS. As with any medical doctor, it is up you as the patient to educate your physical therapist with good information (the IOM criteria for diagnosis is a great place to start). It is energy consuming but imperative for a good working relationship which can be very helpful with the right physical therapist.

Deconditioning is a real secondary comorbidity with ME/CFS and this article (and sounds like those to follow) aims to help identify ways of addressing this piece to allow for ways to improve our quality of life. For some of us that may include a form of stretching and/or very short duration/low load exercise (maybe only 3-5 repetitions of your body weight or up to 2-3 minutes) ON OUR GOOD DAYS, but it is not a cook book recipe.

This is where “listening” to your body and educating your provider comes in – you as the patient are the key ingredient and will largely help to dictate the process. Not everyone will tolerate exercise and if you do it will be a constantly changing picture from day to day.

As for the supplemental oxygen I use, it is a VERY SMALL bandaid which helps me recover from my 2-3 hours of activity (at home or work). It is by no means a cure, nor does it allow me to “do more”, but is helpful as a recovery aide for reasons that are not completely understood. Hope this is helpful Nicole P Rabanal PT, CSCS

Yes it was. Thanks for clarifying a bunch of stuff. Your story in that article was inspiring.. 🙂

Thank you Nicole. I understand that the oxygen is not the miracle cure we are all looking for! But the ice on the head??? When I rest I usually need a hat to keep me warm. Don’t’ you get cold ? Being cold prevents me from relaxing and therefore resting.

Hi Lucie, I use an lavender eye pillow that I keep in the freezer to help ease the severe eye burning and pain, and a corn filled bag (also kept in the freezer) on my head for the low grade fever I usually run. Both warm up in ~10 minutes so it doesn’t take my core temperature down remarkably. It is just enough to take the edge off before my body chills and fleeting numbness set in when I lie down to rest. I too am typically always cold, likely side effect from the medication to help manage my POTS. Be well today 🙂

I am placing a new comment rather than a “reply”, because there have been so many comments now discussing the point I raised above.

Because I have fibromyalgia, not CFS, I think I am right to have discovered that I do not have an impaired aerobic energy system, but that the toxins produced from anaerobic activity and high-effort muscular exertion, are the problem for me. And I think even the first two minutes of exercise, and even the first few seconds, if it is anaerobic, is a problem for me.

I am starting to see more and more differences between CFS and FM, as I become aware of more and more research.

What I have achieved since discovering how important it was for me to avoid anaerobic and “muscle building” intensity of exertion, is that I have raised my aerobic threshold to a much higher level, so that I can now do a lot of things I couldn’t do before, while remaining aerobic. But I can see that this may not be as easy an option for people with CFS, if it is their aerobic system that is broken.

I absolutely understand what so many commenters are saying, that it is very easy to go “too intense” without realising it. If you wear some kind of alarm, you can be very surprised how easily and frequently you trigger it. Often in the course of a day’s normal activities, one needs to “reach” or balance or extend or bend in a way that does place quite high stress on some muscles. One of the big problems with “stretches” is that so often, the position you have to go into to DO the stretch, is stressing many of the other muscles, to the one you are trying to stretch. My solution to this, was to move my stretching experiments into water (hydrotherapy pool or spa pool). Then one can concentrate on stretching one particular muscle, while restfully floating (or partially floating), with nothing else tensing up.

Hi Phil,

I think doctor Davenports important observation here is: exercises need to be very short and of low intensity to be (reasonably) safe.

As he calls himself hands on that notion likely comes from observation rather than from dry theory. Theory then is a reasonable explanation as to why it works and helps setting this 2 minute period. Effectiveness of the protocol can be statistically researched independently of whether this early anaerobe mechanisms is the sole cause or not.

When I look at your “I do not have an impaired aerobic energy system, but that the toxins produced from anaerobic activity and high-effort muscular exertion, are the problem for me” then I can see your experience as being in line with his: don’t do to high-effort muscular exertion. He uses hart rate monitoring as a guide, you may be using pain or common sense as a guide. Or he is more conservative regarding to maximum hart rate then you are just for safety for a wider public. And “don’t build to much toxins from anaerobic activity” could just as well be achieved by going very low effort and time as he proposes.

I for one can now “ride” my electrical bicycle for over 20 minutes at near rest hart rates (I don’t wear a monitor but from time to time count it). I can’t imagine I’m doing this for 20 minutes in this early anaerobic phase. In fact, I *never* ever tried to push my hart rate up (as in “real” aerobic training) since I started my early recovery. Yet now I do activities at significantly lower hart rates then what was before my resting pulse.

To say more: my aerobic capacity significantly increased without doing any aerobic training at all. I believe that is because my short and light activities/exercises do improve blood flow, breathing, train my brain and muscle to be more efficient and learn to exercise with causing less damage to my tissue. All of that combined creates better conditions for aerobic exercise in my opinion (by not having as much tissue damage, having improved recovery from appropriate blood flow, slowly moving toxins out of my muscles without flushing my body with it…).

After all, did your early recovery not start with very short and low intensity exercises as I read? That resembles the doctors protocol quite well. You may just have past this very important first hurdle and now be able to further recover through real aerobic training.

Kind regards,

dejurgen

Dejurgen, I agree totally. I really appreciate sharing these insights. Actually even now, a lot of the exercise I do is at a heart rate below 65% of theoretical maximum. I can sustain a walk, at a heart rate of 90, which used to be my resting pulse rate!

And I too think this is what happens:

“…aerobic capacity significantly increased without doing any aerobic training at all. I believe that is because my short and light activities/exercises do improve blood flow, breathing, train my brain and muscle to be more efficient and learn to exercise with causing less damage to my tissue. All of that combined creates better conditions for aerobic exercise in my opinion (by not having as much tissue damage, having improved recovery from appropriate blood flow, slowly moving toxins out of my muscles without flushing my body with it…)…”

I have symptoms of CFS and fibromyalgia. When I was in high school I started lifting weights – it was supposed to be bodybuilding-style, but I’m sure it evolved to lower reps with higher weights, as young men need to prove how strong they are! And I became quite strong.

After heading off to college I became enamored w/ one bodybuilder, Mike Mentzer, who espoused the “Heavy Duty” style. I started taking all my sets to “failure”. It was during my first year Xmas break that I noticed a significant loss in my ability to recover from workouts. I was showing signs of overtraining, even under low volume workouts.

The pattern I repeated over and over: I would start a new program – Heavy Duty! – and make great gains for about 2-3 weeks. Then, even though I might continue getting stronger, each workout became exponentially more difficult, until I suffered a massive decrease in ability. I would take several weeks off, eventually feel like a bull again, go back to the gym and repeat.

I spent decades trying to understand my body’s betrayal, and attempting to figure out a way around it, but I was looking at diet, supplements, and specific exercises. I was missing the big picture.

I couldn’t repeat sets like other guys: if I went to failure at 12 reps, my second set would fail at 6, the third at 2-3. I couldn’t repeat workouts with the same frequency as others. Throwing in aerobic training destroyed my strength, and I was sick all the time.

I finally (but only sometimes!) came to terms with my condition, and in the last decade (I’m 53 now) found some stability with a program of heavy weights, lifted for few reps, and not getting near failure. E.g., 4 or 5 squats w/ a weight that I could squat 8 times. And only doing 2-3 of these heavy sets. And only one exercise per body area. In this way, I’m using the stored ATP (which is, I believe, the mystery pathway mentioned by Cort). That ATP needs to eventually be replaced, of course, but at your body’s leisure. OTOH, using half that weight would allow 20 reps, but you’d reach the same workload as the heavier set at 8-10 reps and your muscle cells would need to start replenishing the ATP in real time to get to that 20th rep.

The mid-intensity is my metabolic Achilles heel. I’ve had some success running (20-30 second) sprints, and some success w/ super low intensity jogs or hikes. The problem is my ego – I always want to go a little faster, do another rep. And then I pay the cost every time.

This is the best solution I’ve found, but it’s little more than maintenance. I’ve never regained the strength I had when I was 18 years old.

Hi Cort and Gijs… I want to thank you Cort for your simple statement above reporting on ventilation problems and why they might occur… I have reported my extreme issues with breathing I can’t take deep breaths and during crashes can only then take extremely shallow painful breaths which is followed by increasing difficulty talking to the point over the last few months of not being able to speak at all to many specialists who have been completely confused by it…. but the idea that the muscles involved in breathing (and obviously talking) are most affected matches my experience completely and this will help me understand and explain what might be happening for me…

I don’t know if this is the commonest attitude of my fellow patients to exercise, but my attitude is that my goal is to be ABLE to exercise again, and work again. I am so restless like this. I am a smart person who’s bored to death at home. If I could tolerate it I’d work through the pain and exhaustion. But I can’t. This is too much. I haven’t ever seen exercise as a tool of health. I don’t think exercise makes anyone healthy if they aren’t already. I think exercise is a sign of health. It can maintain the health, but it can’t give it to you if it’s gone already.

What irritates me about the “exercise debate” in ME/CFS is that it is often used as a smokescreen from the real issue. What did this to us? Why have decades been lost, treatments been sidelined, scientists jailed, a movie had to be made, etc…? Whether or not we maintain some function due to small bits of exercise is a molehill compared to the mountain of deceit, fecklessness, and victim blaming that we’re up against.

The longer it takes to get the big agencies properly focused on the problem, the harder it will be to shed the toxic situation we have now. Imagine if a drug were found to already exist that fixed this for EVERY patient. Would that be welcomed or would it turn into anger? (Why didn’t you tell us? Why did you wait? Why did my (child) die instead of being offered it?…) The longer we debate things that are of no real benefit, the longer the wound will fester and the harder it will be to clean it and heal it.

Surely any theory, advice or approach which is based on objective measurements of various functions, in real time, (as with the heart monitoring), is a huge improvement on what we or health professionals rely on at the moment? Currently “patient reported” outcomes are often subjective and unreliable based on perception, not actual measured outcomes and data.

The patterns recorded over time could be used for sessions with GPs, or assessments for DWP, Social Care, education or work, if the patients is trying to argue their corner?

The above agencies surely would be unwise to argue with objective data which indicates objectively an explanation in part for limits of functionality?

The Peckerman Q test some years ago did a similar thing, being designed to show cardiac impairment for disability assessments.Check this out again. It was a good read.

At the moment all that is relied on is effectively a wet finger to the wind. That’s not scientific, objective or fair. It’s a crude, lazy, deliberate, method of avoiding cost and refusal by authorities- health, welfare, education and occupation – to confront their obligation and responsibility and deal with the problem.

It also leaves the door open for empire builder who are willing and able to fulfill Government and statutory agencies bidding; to design sloppy research, successfully bid for funds which support the Government’s intended path for reduced liability:; insurance companies likewise.

So I suggest this research and interest is to be welcomed and supported.

Ask yourself, would you rather your child was given this help and advice, try to use this approach or be putting through LP and FITNET?

I know which I would choose! Thanks Cort for stimulating the debate!

On that note it’s great that the Lipkin Research Center is going to develop an app to chart ME/CFS symptoms, stressor and hopefully, steps and activity levels. http://simmaronresearch.com/2017/10/simmaron-lipkin-nih-chronic-fatigue-syndrome-research-centers/

First a practical point. The e-mail pointing to this article has a new sending address, so I found the e-mail in my spam file. Now to add the new address.

I have had good experience with physical therapists needed for a different problem, about 12 to 17 years ago. One dropped have me walk on a treadmill as a “standard” warm up technique. She saw me flagging and stopped it, but she had to see me do it, rather than rely on my own words. The help I needed was anaerobic, not aerobic. I did have the abstracts from two articles by Stace Stevens et al. which she may have read by the second visit.

Coming up to now, when I mark 28 years with this disease, my muscles are visibly shrinking, and this past summer I could not do a short, slow paced walk that I could do 4 summers ago. It was scary this summer, with my body doing things that were totally new to me and rather scary. I presume my heart rate was way up after taking two or three steps, as I was panting (I was not wearing any heart rate counting device) and had to stop, then start again.

Rhinitis began big time. Rhinitis is unpleasant, running down my throat, but it also swells the membranes making it harder to inhale. Something was going on with my heart and lungs that felt scary, and I struggled to describe it, and to realize that I had a comparison of doing the same thing, and now that is lost to me. My thinking was not clear either, or I would have used the Plan B I laid out beforehand, to take a cab for the short walk to the next stop in that family gathering.

I would love to do a program to regain a bit of functionality. I have tried a few times, but I get scared when I have a bad time, which I cannot sort out as being related to my tiny efforts or just a bad spell that is characteristic to my experience of this disease and unrelated to the low level exercise or stretching.

I need an expert to help me learn what is okay, and what is a sign to step back. My current trajectory means my old age will spent in bed totally, no visits to see nieces and nephews and now their children, a few times a year, a grim outlook. I am so pleased to see this article, and wish I lived closer to Workwell to get some expert feedback.

Thanks Sarah for the warning about the blog ending up in your spam folder. We will have a follow up blog focusing in more detail on the exercise/activity protocols and will be looking for PT’s with expertise in ME/CFS.

It seems like there are two meanings to aerobic and anaerobic. One set of meanings is if the body is operating below the anaerobic threshold, which is what gets measured in the tests conducted at Workwell or by Dr. Klimas’s office. Then there are exercises called aerobic, like running or racquetball, versus those called anaerobic, weight training and stretching, from my experience. When I was healthy so long ago, aerobic exercise was meant to raise my heart rate while I performed it; anaerobic exercise was meant to be performed at a constant heart rate. If heart rate increased, the exercise needed to be stopped, and then made easier, not ready for it yet. I think both sorts of exercise can put me, with this disease, into that bad zone shown in the very helpful chart in the article. Is there a way to separate the terms, substitute better terms for exercise meant to raise heart rate, and that not meant to raise it, but to use a muscle or stretch one? And do I understand this at all, the difference between kinds of exercises, and the crucial test to find where the body changes from one state to another as to how the muscles and heart operate and then trigger the disease symptoms?

I read the word “pace” and my brain shuts down and I get nauseous. Can we focus on the cause please?

Many thanks for bringing us this well-written and -researched article. It provides concrete steps that we sufferers can take to help ourselves feel and function better now! That is very rare in the current state of medical treatment for ME/CFS!

I was so happy and heartened to hear of this admirable work being done by the Workwell group! Patients and others should be supporting this type of work, as it provides a functional solution that can be applied now. Sure, it’s a Bandaid, but it’s something! Understanding the root cause of the disease and developing treatments to address the broken energy production system in our disease will likely take years, so I will happily take what I can get today!

Can you please use black and not grey type. Or, at very least a much darker grey. For those of us who must dim our screen in order to use our computers, the lack of contrast makes it very difficult to read and I just simply gave up on this piece.

Will do….Thanks for letting me know.

Maybe I missed this, but after exercising for 2 minutes, how long do we have to wait before doing another 2 minutes of “safe” exercise?

That’s my understanding…

In my above comment I should have clarified that I now consider the word “exercise” to mean anything that is a sustained activity including household chores or taking a shower. I can no longer do exercise like I used to be able to do – ski, bike, run, or even take a long walk. As soon as I do any activity, I must lie down for at least a few minutes to recover from standing up or doing even light activity. Pacing appears to be helpful, but very often, not practical. So, does anyone know how long of a time period that we need to abstain from activity/exercise after 2 minutes of activity?

Hi Tanja,

I don’t know the answer to your question, but what works well with me is to wait until the previous activity (be it exercises, having a conversation, reading something, doing stairs…) is completely out of my system. That is returning to the situation before said activity. That is for me things like hart rate and breathing back to before, anxiety or pace of thinking back to before, feel the same in head and legs…

Hope it’ll do you some good too. If you don’t get that feeling back (within 20 minutes to an hour in my case), chances are that the activity or the combination with previous activities were too much.

Thanks for the helpful suggestions. I can manage to be patient to recover from short periods of activity before going on to the next activity, but find it really difficult to figure out how to manage recovering from long periods of activity such as things that take a few hours/days – errands,occasional travel, long appointments. Seems like it can take several days or longer, and I still have to do the usual chores,etc.and can`t just lie in bed!

Hi Tanja,

If such activities take several days to recover they may be too much. But I totally agree that life goes on and it’s sometimes very hard to avoid.

What may be helpful in those cases (besides the obvious overexerting less wherever possible) is to create “islands of improvement”.

That works by first learning to recover from smaller efforts (waiting until “they are out of your body” as said in previous comment). When that starts to work quite well, it could be tried to do the same for one single moment on a busier day (but not that much busier). Just trying to get it wright half an hour for example and increasing after more exercise with the technique. In such way, if you have keen senses you may learn bit by bit how you “overexert” (what things are exactly the most costly, I did not known for ages) and learn small routines helping you to do these same activities by requiring less effort.

If it would work out well, you may learn a few bits on how to do things more efficiently and hence gain an extra margin. By having more margin you would have to spend less time on hard recovery. One thing I try to do for myself is, if I gain stable improvements over longer time, is to only spend about one third of it on extra activities and use the rest to build a so much needed safety buffer. Spending only one fifth would be even better but I just don’t get there ;-).

It’s not exactly the same as what I did at first as I was searching along the way. Hope it’ll help you.

In case it is helpful for anyone, I recommend a book called Yoga, My Bed, and M.E., by Donna Owens, a PWME in Australia. It’s available on Amazon in print and Kindle form. (The author has a youtube channel as well https://www.youtube.com/results?search_query=yoga+my+bed+and+me) With words and pictures, she explains lots of very gentle yoga stretching and breathing exercises, which she has modified for pwme’s and can be done on one’s bed. She’s very good about advocating backing off on flare-days and she has notes regarding exercises that shouldn’t be done if you have certain conditions, such as migraine or lower back pain. I have been ill for 26 years, and I think it is good for my body to be moving in these gentle ways. I do find it stress-relieving, and I have become a bit more flexible. I have stopped it for weeks or more at a time when I’ve been in bad flares and then started it again. I didn’t mean to go on for so long about this, just thought it might be helpful to some. It is very different than the GET that most of us now know to avoid like the plague. There have been 1 or 2 times that I realized the next day that I may have over done the stretching just a little — and cut down the next time — but nothing severe. Blessings everyone. Here’s the link for the book. https://www.amazon.com/Yoga-My-Bed-M-ebook/dp/B01M0NJ6B2/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1508962232&sr=8-1&keywords=yoga+my+bed+and+me

Thanks for passing that on Randi…

This article on the PTs “getting it” is highly encouraging to me. I’m an old broken down national class distance runner (marathon PR of 2:29). In 1998, I got bit by a tick and contracted Lymn’s Disease. It took a year or so before I could get a ‘fix’ of running. After that I was tempted many times to ‘push it’ and relapsed with a case of Post Exertion Malaise (PEM).

Eventually I went back to using intervals for my physical fitness routine. Typically I would do a version of high intensity interval training (HIIT) running for 20-30 seconds and walking for 100-90 seconds.

This article about Todd Davenport and especially Staci Stevens is very enlightening. From my days doing cardiac and pulmonary rehab, I appreciate their utilization of a slowly progressing, submaximal exercise program that emphasizes the return toward normal activities of daily living (ADLs).

Here are four comments: First, and most important, pacing is vital. The training exercise intensity is not above the ventilatory threshold (so-called anaerobic threshold). For me, I frequently use the talk test: if I can talk in sentences and breathing easily, I am within my training zone. But if I can only talk in phrases and am starting to gasp for air, I am above me ventilatory threshold.

Second, in the beginning of my relapse recovery program, the day’s exercise plan is light intensity interval training (LIIT). Just as Staci does, I slowly work my way up to moderate intensity interval training (MIIT) trying to avoid a HIIT workout.

Third, briefly, submaximal means below maximal aerobic oxygen consumption, and anaerobic means muscles working without oxygen available. BUT it is extremely rare for the oxygen levels in working muscle to decrease to ZERO. For me, the only times that may have happened was when I ran the Pikes Peak Marathon and another up Mt. Evans, both over 14,000 ft. (See me running up Pikes Peak: http://www.endurance-education.com). When we make a transition to increased work levels, we borrow energy from NONAEROBIC energy metabolism in the muscle cellsap and pay it back later from aerobic energy made by the muscle’s mitochondria that is happening. Indeed, if we do have impairments in out ability to use oxygen, Staci has us minimize it. Bravo!

Last, the review written by Davenport, Stevens, and others, “Management of Chronic Fatigue Syndrome/Myalgic Encephalomyelitis,” is thorough and will be a classic. Its discussion of how thresholds for heart rate and for ratings of perceived exertion could be expanded. In fact, this review and its discussion of energy delivery reminds me of a chapter I wrote in the early 1970s (Simonson Books\Weiser Chapter 1 1976.pdf).

All in all, thank you Cort, Todd, and Staci for your contributions for CFS/ME, a mysterious disorder.

I have had ‘Bowen’ every 5 weeks for one hour, which is where the therapist realigns the top layer of muscles in line with my breathing. She will move a few on each side of my body and then leave me 5+ minutes to relax before moving different muscles and resting and repeat, on my front and back.

I could barely walk from my recliner chair to my nearby toilet, and no way I could stand to cook or shower. I had given up driving 7 years ago as I couldn’t drive a few miles to take my son to school with out him pulling my hair and constantly talking to me, to keep me awake! Then I got electric chair so I could once again get around shops myself.

After starting the sessions I slowly felt an improvement in my posture, back and less dragging of my feet. After 9 months of ‘Bowen. I was walking for minutes rather than steps, I could sit a few minutes on a normal chair, I could talk to my friends for long conversations, I could sometimes cook simple meals, drive for longer and teach my two boys to drive.

it’s now been about a year and I recently walked from car and around a convenience store, stood inline to pay and back to the car, in a ‘normal’ way. It felt so strange, like many things I’m doing lately it is blowing my mind that I actually can do things I haven’t done Or done things in a normal way which I’ve not done for at least 7 years.

I can tell winter is coming on with an increase in pain which has been so much lower of late and some stiffness. But saying that I am due for my next session in a few days and my life had been very exhausting and stressful, not being at home due to fire.

I think everyone should try ‘Bowen’ and give it at least once every 4-5weeks over 6 month period if possible. It has helped my Fibromyalgia, M.E, depression and TMJ. It probably won’t even work out at £10 a week.

I hope this inspires some of you and that it helps you too.

God bless you all, sufferers and helpers.

Lisa

I have had ME/CFS for about 23 years.One of my major frustrations is that I can only walk about 20-50 feet. I would love to know if a particular set of exercises would help in getting to walk 10 minutes as described in the conclusion of this article. My son is a PT and could help me with this.