Autoimmune autonomic ganglionopathy is a very rare disease. So why feature it in a blog on chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS), fibromyalgia (FM), and postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS)? Because it could provide a preview of the future. All these diseases feature problems with the autonomic nervous system (ANS). While we know quite a bit about ANS (and other) problems in these diseases, we still don’t know why they’ve occurred. Autoimmunity is a possibility for each of these diseases.

The ANS affects blood flows, digestion, the immune system, heart rate, sleep, etc. When the body needs to respond to a stressor, the fight or flight (sympathetic nervous system (SNS)) is activated. When the stressor is gone, the “rest and digest” (parasympathetic nervous system (PNS)) returns the body to normal functioning. In ME/CFS, POTS and FM, the fight or flight system has become unusually activated.

There was a talk on autoimmune autonomic gangliopathy (AAG) given by Steven Vernino at the recent Dysautonomia Conference.

Autoimmune autonomic gangliopathy (AAG) is interesting because it demonstrates how the immune system can take a two-by-four to the autonomic nervous system. Given the many people with ME/CFS, FM and POTS whose diseases were triggered by an infection; i.e. an immune response – that’s an intriguing fact.

Steve Vernino related how one 50 year old woman’s AAG began with a cold! Four days later, she was admitted to hospital with severe nausea, abdominal pain, tingling, blurry vision, and dizziness. Her blood pressure was doing weird things: lying down, her blood pressure was high normal, but standing up, it dropped to 80/56 (!).

Since the ANS regulates blood pressure, those strange blood pressure readings suggested that her ANS wasn’t functioning properly. Other signs – dry mouth, enlarged pupils, and lack of sweating – also pointed to problems with the ANS. Her sensory and motor nerves – which run alongside ANS nerves – on the other hand, were normal.

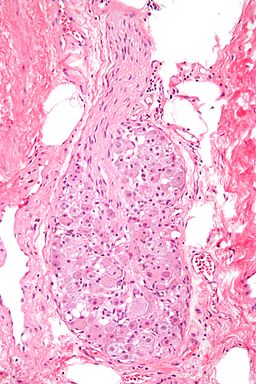

What had happened? Autoimmune autonomic ganglionopathy (AAG) is a rare disease, but researchers ultimately uncovered what was going on. The ANS produces two kinds of nerve “ganglia” – areas where the nerves collect together. The parasympathetic nerve ganglia are found near the organs, while the sympathetic ganglia are found close to the spinal cord. Acetylcholine is used to open up a channel between one neuron and another – and activate the nerves.

Studies uncovered the presence of antibodies in AAG patients which attack the anti-nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (AChR) that are responsible for opening up the channel between two autonomic nerves. With the channel blocked, the signal cannot pass and the ANS cannot work. That’s why her blood pressure dropped severely when standing up. It’s why she had so many gut problems.

She had something characterized as acute pandysautonomia; i.e. a rapid onset of autonomic nervous system failure. It’s been known since 1969 that Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) – the same virus responsible for triggering ME/CFS in many people – can trigger it. Some people with this experience a partial spontaneous (i.e. untreated) recovery, but full recoveries are rare. A simple cold had changed this person’s life forever.

In AAG, both sides of the ANS fail. The sympathetic nervous system fails to kick in during standing, resulting in low blood pressure (orthostatic hypotension) and problems with gut motility. Parasympathetic failure, on the other hand, leads to dry eyes and mouth, bladder problems, sexual impairment, low heart rate variability, and big pupils which do not respond to light.

People with AAG experience “autonomic failure”, which is rare. In autonomic failure, their nerves simply stop working. In dysautonomia, which is much more common, the autonomic reflexes work but the balance between the SNS and the PNS is off. Some people have a combination of both.

As so often occurs in autoimmunity, there was a lot of grey area that took time to clear up. AAG was originally diagnosed when the AChR antibody levels were .05, but the diagnostic criteria are stricter now, and the cutoff for the disease is 4 times higher (from .2 up to 5). At lower than .2, 50% of those with the antibodies have no autonomic symptoms at all.

This reveals another tricky aspect of antibodies and autoimmune disease: deleterious antibodies can be present without causing many problems; i.e. it’s often the level of the antibody which counts. Researchers now know that AChR antibodies become “clinically significant” when they’re .2 and over, and generally don’t cause problems at lower levels.

They’ve also learned that different grades of AAG exist. People with very high levels of antibody levels early typically get sick very rapidly and experience severe autonomic failure. People who present with lower levels of antibodies early on typically have limited autonomic failure. As it may be in ME/CFS, the ferocity of the early immune response apparently makes a big difference. The damage, in other words, is done early.

As in ME/CFS, FM, and POTS, most of those afflicted with AAG are women. As in these diseases, many (50%) report a viral onset, but gradual onsets also occur. The disease is also associated with joint hypermobility, MCAS, other autoimmune diseases, and higher levels of autoantibodies in general.

Treatments often involve immunosuppression (IVIG, plasma exchange, Rituximab, steroids) and can be very effective in some cases, but can come with side effects as well. Symptoms improve when antibody levels drop. Other treatments include standard treatments for orthostatic intolerance (droxidopa, pyridostigmine, midodrine.)

In what’s surely another potential lesson for heterogenous diseases like ME/CFS, FM, and POTS, some people with acute autonomic failure don’t have any antibodies. Instead, they have an inflammatory neuropathy: the receptors for their autonomic nerves are being destroyed by inflammation. Same outcome – different pathway.

Autoimmunity in POTS and ME/CFS

In AAG, autoimmune or inflammatory processes prevent the autonomic nervous system receptors from relaying messages from autonomic nervous system nerves. That results in autonomic “failure” – something that’s not generally seen in ME/CFS or POTS. Instead, these diseases generally feature dysautonomia – a failure to properly regulate the ANS.

Still, some of the symptoms and signs seen in AAG (problems standing, gut issues, small fiber neuropathy, low heart rate variability), are also found in ME/CFS, FM, and POTS. Plus, just as with AAG, most patients are women, the diseases are often triggered by an infection, and they’re allied with other disorders such as Ehlers Danlos Syndrome (EDS) and mast cell activation syndrome (MCAS).

Given the similarities present, the question arises if an autoimmune or inflammatory process is also targeting the autonomic nervous systems of ME/CFS, POTS, and FM patients?

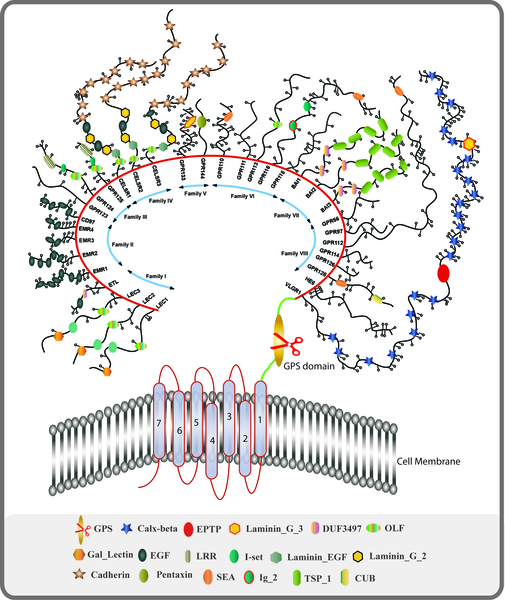

The big target right now is the GPCR family of receptors. This large family contains several receptors that have been associated with autonomic disorders such as AAG, Sjogren’s Syndrome, POTS, and possibly ME/CFS.

Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS)

There’s much grey area in ME/CFS. It should be noted that the autoantibodies that may play a role in it are believed to be natural regulators of autonomic functioning. They become pathological when they’re too prevalent and either overactive or inhibit ANS functioning.

Elevated M3 and M4 muscarinic and β2 adrenergic autoantibodies that were associated with immune abnormalities have been found in ME/CFS. A recent study suggested that B1 and B2 adrenergic antibodies were associated with structural changes in the brain.

Another study found elevated autoantibodies in the plasma, but not the cerebrospinal fluid. It did not, however, find that they were associated with increased symptoms – an essential requirement for an autoimmune disease. Whelan introduced some more mystery when he recently reported at the IACFS/ME conference that he did not find that the antibodies that have been associated with POTS were elevated in ME/CFS patients with POTS. He did find a correlation between autoantibody levels and the presence of small fiber neuropathy (SFN).

Small studies suggest that immunoadsorption may be able to reduce the levels of these antibodies – and reduce symptoms. Rituximab has taught us, though, to be wary of the findings of anything but larger placebo-controlled studies. It’s not easy to validate autoimmunity in disease and the search for an autoimmune cause of the ANS problems in ME/CFS is still in its infancy.

Recently, though, a group of researchers including Carmen Scheibenbogen and Manual Martinez-Lavin proposed that chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS), POTS, and complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS) belong to a new category of diseases they called “autoimmune neurosensory dysautonomias”, defined by problems with the GPCRs.

Wirth and Scheibenbogen have also proposed that these autoantibodies are narrowing or vasoconstricting the blood vessels, reducing blood flows and oxygen consumption. They believe the blood flow problems may lead to an increase in vasodilators such as bradykinin, which produce pain, fatigue and other symptoms.

Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome (POTS)

Much more evidence of GPCR issues is present in POTS, but the studies have tended to be small. Still, several studies have found increased levels of antibodies against alpha and beta-adrenergic and/or muscarinic receptors. Last year, a study found elevated autoantibodies against the alpha 1 adrenergic receptor (89%) and the muscarinic acetylcholine M4 receptor (53%). As with AAG, an exposure to EBV was noted. Sympathetic nervous system activation, problems with blood flows, reduced blood volume could all be explained by problems with GPCRs.

Last year as well, the autoimmunity hypothesis in POTS took a step forward with the production of an animal model. The study was small, but it nevertheless suggested that an autoimmune response to A-1 and B1 adrenergic receptors would be likely to produce the high heart rates and reduced blood pressures seen in POTS. While recognizing that substantial work remains to be done, two researchers asserted that the production of the animal model was “crucial for future POTS research“.

Another step forward was taken with the publication of a paper showing that the serum (blood) from POTS patients produced an unusual activation of the receptors under question. That activation was, in turn, associated with problems standing and walking. POTS needs larger studies, and comparisons with different disease groups, but POTS seems like it’s getting closer.

Recently, a fibromyalgia study that used IgG from FM patients to create a fibromyalgia-like mouse, suggested an autoimmune process may be activating pain-producing neurons found just outside the spinal cord and producing small fiber neuropathy.

Conclusion

AAG is a rare disease in which autoantibodies target autonomic nervous system receptors and produce autonomic failure – and quite a few symptoms which overlap with ME/CFS, POTS, and FM. It took some time to understand which levels of autoantibodies had clinical significance. Over time, it also became clear that some cases of AAG are inflammatory in origin – not autoimmune.

ME/CFS and POTS are different and similar. All three diseases feature problems with the autonomic nervous system and have some connection with joint hypermobility and mast cell activation syndrome. The dysautonomia problems in ME/CFS and POTS appear to be the result of autonomic regulation, not autonomic failure. If an autoimmune process is present, it’s likely causing increases in naturally occurring antibodies which dysregulate the autonomic nervous system.

Research more and more suggests that a subset of POTS is autoimmune in nature. An animal model has been produced and POTS researchers have gone beyond measuring antibody levels to assessing the effect blood from POTS patients has on receptor responsiveness. Larger studies are needed, though, to validate the finding – and potentially blow open the door to the possibility of using autoimmune drugs in POTS.

The hunt for an autoimmune cause of the autonomic problems in ME/CFS is on. Interestingly, one of the same autoantibodies found in POTS also appears to be found in ME/CFS. While some results are promising, others are puzzling. We’re still at the beginning of understanding the role autoimmunity may play in the autonomic nervous system issues in ME/CFS.

It seems that during many infectious diseases autoimmune reactivity is increased. I.e., whenever the immune system fights certain infectious diseases there may also be a biological opportunity for persistent, then pathological autoimmunity to develop.

This has just been shown for SARS-CoV-2:

https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.10.21.20216192v1

Possibly genes or other biological influences may determine which autoimmune targets are being primed.

“Another step forward was taken with the publication of a paper showing that the serum (blood) from POTS patients produced an unusual activation of the receptors under question.”

Is this possibly another instance of something in the blood (of a sick person) signaling to the cells to behave a certain way??

My thought exactly..

That seems to speak of Cell Danger Response model.

I wonder if they have measured ATP, if it could be leaking as well…

I have a hard time seeing autoimmunity in my case.

Long before ME/CFS and PEM entered my vocabulary, already in infancy I had symptoms of glitches in energy metabolism. The beginnings of POTS, of MCAS. They were there.

It would seem more metabolic in nature. And a strong genetic component – every single person in my family seems to have an energy production problem.

My answer to your second comment. I will hold it short because of my brainfog and as english ist not my maternal language. I personally believe, it’s not an autoimmune disease, or at least not in all cases (I mean diffirent grades and sometimes symptoms).

There are a lot of reasons, but my brain doesn’t work to call all of them 🙁 for me its more a metabolic/enzyme deficiency problem. For exsmple PEM. And it’s important to know, that an enzyme deficiency can also start with an infection, flu/cold, stress etc. if you have a predisposition at every age. That means your body can compensate this deficiency and will have no symptoms or just a little. Then a flu/cold -> oxidative stresse (as far as I can remember) and then you have a chronic illness. How I already said, there are more reasons, but I am not possible to write that much + brainfog. I have this illness since my childhood, that is why I see or feel it like an metabolic or enzyme deficiency illness. And that is why I am so sad to see that there is more focus on autoimmunity. I think that research should be balanced.

Sorry for my mistakes:)

Ah… yes:

Our doctors usually do a good job of ruling out common conditions before arriving at clinical diagnoses (of ME/CFS, FMS, hEDS).

It falls on us to persuade them to investigate rarer conditions, such as inherited metabolic disorders. Hopefully with their help, we can get the testing needed to rule out/confirm. There are ways to do it on your own as well, depending on where you live and resources.

It may be that one has just one copy of a gene mutation, what they call ‘carrier’ that may not be as innocent as being a carrier… I have met a few under this predicament who improved their health nevertheless treating it as if it were a disorder. Maybe with time and research we will learn what the full impact of carrier status or common polymorphisms may have on health.

I feel you, in regards to the PEM and brain fog. May you find an intervention (or two) to ameliorate it! 😉

I have not seen anyone mention Chronic Inflammatory Response Syndrome or CIRS. Check out dr Richie Shoemaker about mold illness. survivingmold.com. It’s a genetic issue.

It comes with most of the symptoms mentioned plus all the brain fog issues and more listed below.

Also no one here has mentioned mood swings, angry outburst, feelings overwhelmed and of dying.

It is discouraging that: “A recent study suggested that B1 and B2 adrenergic antibodies were associated with structural changes in the brain.”

I think I recall Ron Davis saying a couple of years ago that he did not think cfs was autoimmune. Wonder what he thinks now.

We’re still really pretty much at the beginning of the search for autoimmunity. Time will tell. It takes a lot to prove autoimmunity. For me, I thought it was interesting that inflammation can cause the same symptoms as autoimmunity in AAG.

After starting the long term “good day, bad day” study, I thought that Jared Younger released early results saying that about a third of the patients had symptoms that tracked with fractalkine (indicating an auto-immune etiology), a third had symptoms that tracked with CRP (suggesting an inflammatory / infectious etiology) and a third didn’t track with anything and might be metabolic. Is this still correct? Is fascinating how anytime researchers investigate illness subtypes, how often the subsets fall out around 30-40% (Lipkin, Prusty, Scheibenbogan, etc) , suggesting Younger might be right, and possibly explaining why rituximab worked spectacularly for some and not for others. I have always thought that diabetes would also be a potential model for ME/CFS with both metabolic and auto-immune origins, but with stress hormones / neurotransmitters and not sugar acting as the major culprit and messing up the CNS / ANS receptors.

Excellent Article, thanks so much Cort. As a POTs patient who was only diagnosed after many years this is so heartening to see so much research coming through now. Hopefully the cure lies in the cross over in all of these conditions.

That’s what I’m thinking – there is a crossover occurring.

Sounds very similar to paraprotinemia (monoclonal gammapothies/MGUS), Paraprotinemic Polyneuropathy and Chronic inflammatory Demyelating polyneuropathy (CIDP/Latent Myasthenia Gravis), POEMS etc.

I was investigated for stable Paraprotinemia and Myeloma Cancer for 4.5 years. Whilst suffering from MECFS, Fibro, possible POTS, CCI and EDS (undergoing diagnostics).

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4731930/

Interesting blog as usual Cort!

I started digging some deeper.

I suspected acethylcholine and choline might be problematic as the nerve cell receptors require quite a bit of it and acethylcholine and choline are related to methylation. Many ME patients might have problems with methylation left or right. It didn’t fit a main role in this story I felt however.

When looking at Wikipedia(Nicotinic_acetylcholine_receptor) my eye was caught by following part:

“Receptor desensitisation

Ligand-bound desensitisation of receptors was first characterised by Katz and Thesleff in the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor.[24]

Prolonged or repeated exposure to a stimulus often results in decreased responsiveness of that receptor toward a stimulus, termed desensitisation. nAChR function can be modulated by phosphorylation[25] by the activation of second messenger-dependent protein kinases. PKA[24] and PKC,[26] as well as tyrosine kinase,”

I remembered that Issie less then a week ago happened to have mailed her latest finding on MCAS (something she suffers a lot from). It’s a paper with title “The tyrosine kinase network regulating mast cell activation” from “Alasdair M. Gilfillan and Juan Rivera”.

The title says a lot: Tyrosine kinsases regulate mast cell activation (strongly MCAS related!).

It’s a very technical read I mostly avoided, but it seems to say that several different tyrosine kinases (not only the KIT thing seeming the worst subtype) seem to increase mast cell activation. Other papers reveal likewise links between (some subtypes of) tyrosine kinases and MCAS.

Now, going back to Wikipedia(Nicotinic_acetylcholine_receptor):

“nAChR function can be modulated by phosphorylation[25] by the activation of second messenger-dependent protein kinases. PKA[24] and PKC,[26] as well as TYROSINE KINASES”

=> It seems that a main class of chemicals that seem to be involved in mast cell regulating / activating are also modulating anti-nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (AChR)

=> Chemicals used in immune (mast cell) signalling seem to interfere with nerve and brain signalling.

As the conditions the research mention borderline MCAS problems, it sounds quite plausible. Unlike what I thought before, I too have frequent mast cell activation. Issie learned me to recognize the signals better (I’ll leave explaining that to her, she’s the expert). While she has very strong bouts of spike release, I who have no POTS but some undefined orthostatic intolerance have a very frequent but lower level (over) activation of mast cells. I can almost set my clock on them for coming in after eating food.

From Wikipedia(Mast_cell#In_the_nervous_system)

“In the nervous system

Unlike other hematopoietic cells of the immune system, mast cells naturally occur in the human brain where they interact with the neuroimmune system.[4] In the brain, mast cells are located in a number of structures that mediate visceral sensory (e.g., pain) or neuroendocrine functions or that are located along the blood–cerebrospinal fluid barrier, including the pituitary stalk, pineal gland, thalamus, and hypothalamus, area postrema, choroid plexus, and in the dural layer of the meninges near meningeal nociceptors.”

=> Mast cells are also present in the brain (note: in regions often suspected to go wrong in ME), so there will very likely also “tyrosine kinase” signalling steering these mast cells.

From a paper titled “Astrocytes and microglia play orchestrated roles and respect phagocytic territories during neuronal corpse removal in vivo”:

“The relative involvement and phagocytic specialization of each glial cell was plastic and controlled by the receptor tyrosine kinase Mertk.”

From a paper titled “[3H]taurine and D-[3H]aspartate release from astrocyte cultures are differently regulated by tyrosine kinases”

“Volume-dependent anion channels permeable for Cl- and amino acids are thought to play an important role in the homeostasis of cell volume. Astrocytes are the main cell type in the mammalian brain showing volume perturbations under physiological and pathophysiological conditions.”

=> Taurine is a strong osmolite (a substance attracting water). Releasing it helps regulating water housholding, something fairly important in POTS (and regulating CSF pressure too). Tyrosine kinases seem thus to influence how astrocytes regulate this.

From a paper titled “Tyrosine kinase Fyn regulates iNOS expression in LPS-stimulated astrocytes via modulation of ERK phosphorylation”:

“At basal levels, iNOS expression is low, and proinflammatory stimuli induce iNOS expression in astrocytes, microglia, and oligodendrocytes. Fyn, a non-receptor tyrosine kinase, regulates iNOS expression in several types of immune cells. However, its role in stimulated astrocytes is less clear. In this study, we investigated the role of Fyn in the regulation of lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced iNOS expression in astrocytes from mice and rats. Intracerebroventricular LPS injections in cortical regions enhanced iNOS mRNA and protein levels, which were increased in Fyn-deficient mice. Accordingly, LPS-induced nitrite production was enhanced in primary astrocytes cultured from Fyn-deficient mice or rats. Similar results were observed in cultured astrocytes after the siRNA-induced knockdown of Fyn expression. Finally, we observed increased LPS-induced extracellular signal-regulated protein kinase (ERK) activation in Fyn-deficient astrocytes. These results suggested that Fyn has a regulatory role in iNOS expression in astrocytes during neuroinflammatory responses.”

Note: LPS is the stuff that a large class of bacteria release when attacked or forming biofilms.

=> That’s complex stuff for saying protein kinases play an important role in brain immune cells.

From a paper with title “Eph receptor tyrosine kinases regulate astrocyte cytoskeletal rearrangement and focal adhesion formation”

=> Hard to understand, but it says tyrosine kinases regulate astrocytes to an important extend.

Looking back at Wikipedia(Nicotinic_acetylcholine_receptor):

“17 vertebrate nAChR subunits have been identified, which are divided into muscle-type and neuronal-type subunits.”

“The nAChR subunits encoded by this locus form the predominant nicotinic receptor subtypes expressed in the peripheral nervous system (PNS) and other key central nervous system (CNS) sites, such as the medial habenula, a structure between the limbic forebrain and midbrain involved in major cholinergic circuitry pathways”

“Nicotinic receptors containing α6 or β3 subunits expressed in brain regions, especially in the ventral tegmental area and substantia nigra, are important for drug behaviors due to their role in dopamine release.”

Looking at the bottom table, you see over half of the nAChR receptors in that table being related to the brain.

=> If those nAChR receptors in the brain would be “vulnerable” to tyrosine kinases too and if those would happen to overlap with the specific tyrosine kinases used to control / modulate / fire the brain mast cells, astroglia and microglia then brain immune activation can sure interfere with brain wide neuron signaling. That’d mess one up!

=> If the specific tyrosine kinases that steer part of the immune system overlap the ones that are affecting the nAChR receptors, then a strong persistent immune activation sure could mess up *ALL* neuronal activity including brain functioning (all of it with a stronger impact on the neuronal hormone controling and motor neurons it seems at first glance), the sympathic and parasympathic nerve system and the autonomous nerve system.

=> If so, it would act pretty much as what Cort described: resembling the effects of autoimmune autonomic gangliopathy without necessary an actual auto immune process and the associated permanent damage.

Here the “English” summary of this text wall:

Mast cells, present in body and brain, and microglia and astrocytes, present in the brain are “fired” quite strongly by a class of chemicals called “tyrosine kinases”.

The signaling of neurons, including nerve fibers, the brain and autonomous nerves controling the heart is strongly influenced and controled by nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (AChR).

Those nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (AChR) apear to be sensitive to chemicals in the class “tyrosine kinases”.

While that does not need to be all the same chemicals (as there are many different subtypes of tyrosine kinases), it sort of screams that some specific tyrosine kinases might both control several types of immune cells and (the signaling speed and strength of) neuron cells.

If so: then we could have a STRONG interference of chemicals firing up the immune system with (near) ALL neuron functioning over our entire body! That would VERY much resemble the auto immune disease that Cort describes. It would not be an auto immune process nor an inflammatory process *damaging* the neurons, but the chemicals to fire the immune cells interfering with it.

Looking further into the above idea (rather then sleeping as I should), I got the hunch that both neurons and several types of immune cells share the same (or almost the same) type of receptors: nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (AChR).

What those tyrosine kinase class of chemicals do is modifying proteins to phosphorylate a specific tyrosine amino acid on it. From Wikipedia(Tyrosine_kinase):

“A tyrosine kinase is an enzyme that can transfer a phosphate group from ATP to the tyrosine residues of specific proteins inside a cell. It functions as an “on” or “off” switch in many cellular functions.

Tyrosine kinases belong to a larger class of enzymes known as protein kinases which also attach phosphates to other amino acids such as serine and threonine. Phosphorylation of proteins by kinases is an important mechanism for communicating signals within a cell (signal transduction) and regulating cellular activity, such as cell division.”

What I’ve read so far is rather complex science, but either specific tyrosine kinases can modify the protein of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (AChR) itself or they can modify a signaling protein triggered by activating these acetylcholine receptors (AChR).

Either way, if I get it right specific tyrosine kinases can modify how strong a cell reacts to “an input” or a “chemical trigger” by working on its nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (AChR) on the surface of the cells.

Now if both neurons and immune cells like mast cells had nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (AChR), then they would get very close to be sensitive to the same subclass of tyrosine kinases: those affecting the nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (AChR).

When rereading Wikipedia(Nicotinic_acetylcholine_receptor), it *seems* (I’m by far no expert on them) that there is but one type of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (AChR), but with different subunits and “activated combinates” depending on the cell type:

“It has also been discovered that various subunit combinations could form functional nAChRs that could be activated by acetylcholine and nicotine, and the different combinations of subunits generate subtypes of nAChRs with diverse functional and pharmacological properties.[37] When expressed alone, α7, α8, α9, and α10 are able to form functional receptors, but other α subunits require the presence of β subunits to form functional receptors.”

That is complex, but it *seems* to indicate that the specific class of tyrosine kinases that affect different subunits of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (AChR) *could* have quite an overlap.

In more plain words: specific tyrosine kinase chemicals that modulate mast cell activity have a fair chance to modulate neuron activity fairly similar. Otherwise said, if the body would release a mix of tyrosine kinases to upregulate (quicker triggering) mast cell degranulation, it has a fair chance to make neurons fire faster too.

That of coarse would require that not only neurons but also mast cells would have those nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (AChR). That is exactly what a 2006 study titled “Nicotinic acetylcholine receptors on basophils and mast cells” found:

“The aim of this study was to investigate whether nicotinic acetylcholine receptors are present on a human basophil and mast cell lines as their presence may suggest a mechanism of associated anaphylaxis. Nicotinic receptors were demonstrated on a basophil and a mast cell line using an α‐bungarotoxin–fluorescein conjugate by flow cytometry and by both conventional and confocal microscopic techniques. The identity of this receptor was confirmed by reverse transcriptase PCR and quantitative PCR.”

Since then, these findings have been confirmed by independent research, for example totally different people who wrote the paper titled “IgE-induced degranulation of mucosal mast cells is negatively regulated via nicotinic acetylcholine receptors”.

Very technical bit from Wikipedia(MuSK_protein)

“MuSK (for Muscle-Specific Kinase) is a receptor tyrosine kinase required for the formation and maintenance of the neuromuscular junction. It is activated by a nerve-derived proteoglycan called agrin.

MuSK signaling

Upon activation by its ligand agrin, MuSK signals via the proteins called casein kinase 2 (CK2),[1] Dok-7[2] and rapsyn, to induce “clustering” of acetylcholine receptors (AChR). Both CK2 and Dok-7 are required for MuSK-induced formation of the neuromuscular junction, since mice lacking Dok-7 failed to form AChR clusters or neuromuscular synapses, and since downregulation of CK2 also impedes recruitment of AChR to the primary MuSK scaffold. In addition to the proteins mentioned, other proteins are then gathered, to form the endplate to the neuromuscular junction. The nerve terminates onto the endplate, forming the neuromuscular junction – a structure required to transmit nerve impulses to the muscle, and thus initiating muscle contraction.

Role in disease

Antibodies directed against this protein (Anti-MuSK autoantibodies) are found in some people with myasthenia gravis not demonstrating antibodies to the acetylcholine receptor.[3] The disease still causes loss of acetylcholine receptor activity,[4] but the symptoms affected people experience may differ from those of people with other causes of myasthenia gravis.[citation needed]”

Roughly saying IMO something like:

* a Muscle-Specific Kinase induce “clustering” of acetylcholine receptors (AChR); that sound like sort of “rearanging them” to me.

* people who have this not working have loss of acetylcholine receptor activity and that is a bad thing as it plummets signalling.

The idea of these nicotinic acetylcholine receptors being the same impacted by tyrosine kinases for neurons and mast cells seem to indicate that if we have mast cell activation then that we should have quicker firing neurons, not slower firing neurons.

The research Cort reports on seems to indicate the opposite however: that nerves are slow to conduct signals.

This does not need to be a contradiction however. There are options to align those two.

A) chronic over activation of neurons easily could exhaust them and make them respond sluggish despite over activation by these tyrosine kinases.

B) the immune system might not be chronically over activated but frequently swing between activation and “being depleted and rest flat on the face”.

A) would be a bit similar to our immune system both showing properties of being too strongly activated and of it to have no strength in fighting pathogens (like the too weak NK cells).

B) would be close to how a “real” MCAS/POTS patients (or at least Issie with andrenic type of POTS) seems to feel: when having an MCAS event the brain is “going in hyperdrive” and racing like hell.

It also would ressemble a lot how I feel at the onset of crashing: weak but tense muscles (muscle activation doing plenty but different parts of the muscle doing different and opposite things rather then trying to act as onewith muscles tending to be “to strongly contracted”), very strong pain shoots (increased, plentifull and random / noisy” signalling of pain nerves), confusion and very strong anxiety (brain signals acting very incoherently producing near no results (confusion) but neurons massively and quickly firing (high anxiety)).

A) could still be a contender: sometimes overactivating of neurons and nerves could be hard to distinguish from underactivating: if there is underactivating then the muscle does few (but IMO should be more relaxed), if there is overactivating then the muscle does few too (but IMO should be constantly tense and at near full contraction). In both cases few work can be done. The later fits ME/FM: tense contracte muscles and few ability to use force as the muscle is already close to full contraction.

I suspect both our immune activation and our neuronal activation to vary a lot over the course of a day but to be set to high most of the time. That would be combining option A and B during over the coarse of a day. High immune activation does not need to be good at fighting pathogens, just as high neuron activation does not need to mean a clear brain fog free head.

In myastenia gravis, a true damage of muscle atached neurons is observed and that should result in loss of signaling. That AFAIK goes with muscle weakness of the “relaxed” type. Think about dropping eye lids for example. We seem to have the opposite: muscles fully tensed up rather then fully relaxed. The ability to do physical effort and exert force would be similar: few in MG as you can’t contract your muscles any bit and few in ME as they are already near fully contracted “at rest” and you can contract them few extra.

Here’s the “English summary” of the “common nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (AChR)” idea:

* Neurons have nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (AChR).

* Mast cells have nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (AChR).

* Tyrosine kinases are a wide class of chemicals modifying tyrosine parts of proteins.

* Tyrosine kinases that affect nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (AChR) should be only a small subset of all available tyrosine kinases in our bodies.

* With that, chances are fair that (at least some) tyrosine kinases that are used to fire our mast cells quicker (and some other types of immune cells) would do roughly the same with neurons: fire them quicker.

* If so: chronic immune issues would have IMO quite a high chance to result in chronic neuron signaling issues (as neurons also fire more rapidely if there are many chemicals present that make mast cells fire more rapidely).

* Those chronic neuron issues, seen in the form of “incorrect firing of neurons of all kinds” could fairly easily result in:

– wrong and too strong pain signaling (FM)

– very frequent “tense” muscles even at rest (ME) (and / or FM?, I have both)

– frequent anxiety, brain fog, sensory overload, chemical sensitivity, brain being lit like a Christmass tree under a scanner when doing or observing anything (ME)

– poor control of autonomous functions like blood vessel contraction and dilation, heart rate and prefil, bladder control… (ME, FM?)

– a strong tendency for blood vessels to be overly contracted just like the muscles rahter then them to be over dilated (ME, FM, POTS)

– poor regulating of hormones as, as far as I found in this short time, nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (AChR) are high in the regions controling hormone regulation (ME)

– (possible) poor CSF pressure control as nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (AChR) *seem* to be high on one region co-regulating CSF (ME, FM, Migraine)

I believe ME/CFS is 2 distinctly different maladies. We know the only defining symptom for ME/CFS itself is ‘post-exertional malaise’ and I believe it will be answered in Dr. Ron Davis’s research at Stanford. If our cells aren’t getting the oxygen and glucose needed to fire, the body thinks it is in constant peril. It goes to the back-up system, which is adrenaline, but our adrenal sacs are empty from overuse. Dr. Davis’s research so far indicates an issue in the 24/7 monitoring cycle of Cortisol (stress hormone) to ACTH to adrenaline. It looks like the main issue is in the ACTH phase between cortisol and adrenaline, so if we get to the adrenaline stage, it’s already too late.

The second part of ME/CFS is where we show so many symptoms of other diseases, like West Nile Virus, Fibromyalgia, Lyme Disease, PTSD etc. I think they have similar problems to ours, in that they also think the body is in constant peril, just like the ME/CFS example above. We share 24/7 fight or flight issues like them, but each has different causes. I think this is now known as Central Sensitivity Syndrome (CSS).

By looking at shared symptoms and trying to trace them back to a cause, researchers get mired in similarities in CSS diseases. It’s why so many studies show so many abnormalities, but they aren’t going to be solved until the base cause of each is understood.

Which brings me back to ME/CFS. So many different illnesses result in being stuck in fight or flight of CSS. With ME/CFS, we can’t afford to waste research dollars, so I would like to see our research money go to the anabolic trap and similar research, rather than the CSS symptoms, which can be studied by other researchers with deeper pockets.

This is my thought too ”If our cells aren’t getting the oxygen and glucose needed to fire, the body thinks it is in constant peril. It goes to the back-up system, which is adrenaline, but our adrenal sacs are empty from overuse. ”

Certainly it is my experience that I am in flight/flight all the time – the big question is how that happens – whether it’s because of blood flow/oxygenation/ATP/inflammation or other issues.

I’ve been wondering along the same sort of lines as you Per, for a while. Plenty of people are highly stressed, have chronically activated their stress response and also may have all sorts of health issues but what is it that is central to ME/CFS, that makes it different to these other illnesses?

I used to be a person who could have boundless energy. I’ve done some fairly ‘challenging’ sort of jobs, where I’d start at 8am on a Saturday and finish at 4pm on a Sunday, having also ‘slept over’, as part of my 48hr working week. No problem. Even if I became really tired, stressed out etc., I could always bounce back. My family are mostly sporty, outdoors, energetic kind of people.

So how did I get to the point a few years ago, that I absolutely had to limit my thoughts (especially emotionally loaded ones) because I didn’t have enough energy to run my body’s essential functions and have thoughts that drained my depleted energy supply? I’ve never encountered anything like it before. I was on the verge of a complete collapse of my whole system. I was aware that I was existing on nervous energy but my body was increasingly unable to keep up with the demand.

For me, in my situation and my issues I had to calm my stress response and get better sleep because I was getting worse and my health situation was completely unsustainable. I was funding my existence on credit but the debt was being called in and I couldn’t keep up with the repayments. I had bankrupted myself.

Now I’m trying to live within my means. I’m working away at any ‘unfinished business’ that drains my energy. I’ve been trying to support my body by eating nutritious food and I take various supplements because I feel my body has taken such a hit over the last while – it needs all the help it can get.

I’m drawn to the metabolic trap, the cell danger response and Jarred Younger’s ideas about brain inflammation. I try and not irritate my brain and I’m focusing at the moment on trying to achieve a sense of grounded calm and personal empowerment, despite everything that’s going on in the world.

In some ways I am disregarding what I call my health issues because I find that limiting. Do I have ME/CFS or not? Will I be kicked out of the group if I don’t ‘fit in’?

I used to be a person who managed to find a path to having boundless energy and then I lost it. Can I find my way back?

All very complicated, so this is what I take from what I understand! Eating food is one of the activities we undertake daily, that brings us closest to our environment.

Apart from my fairly recent development of asthma and long term very mild eczema (food related – dairy) eating certain kinds of food is a reproducible way for me to activate my immune system. The most disruptive and concerning immune reactions occur in my brain and my heart. If my brain becomes very agitated then I find it difficult to think, my mood becomes black and treacherous, my balance is off and I’m just thinking I can’t remember what else and that reminds me! – my memory goes 🙂 Actually that’s a very clear indicator – I regularly check my bank balance online and if I’ve set my brain off, I can’t remember my number to access my account.

However, as this is food related – mainly sugar and probably preservatives, artificial colours etc – processed food is not helpful. So I try to eat an anti inflammatory diet and try to limit the sugar.

So I can make my brain inflammation worse or better.

Also, apparently every time we eat our digestive system gets ready for the ingestion of something that may be harmful – it doesn’t want to be caught out. I used to follow Yasmina (the low histamine chef) before she sadly died from breast cancer – and I think that’s who mentioned the inflammatory response to eating.

Interestingly Yasmina also moved from trying to eliminate histamine from her diet, to incorporating a manageable amount because I think she believed the body would make histamine anyway.

I may be completely off topic but I’ve started so I’ll finish off what I was thinking…

Fairly recently – like early 2019 – I was intolerant to so much food, I could hardly eat anything without experiencing a reaction. My blood pressure would sky rocket, my brain seemed to run out of energy – the stakes were high. I wanted to be able to eat olive oil but every time I did, my throat would swell up – not enough to stop me breathing but enough so that I noticed. It became especially apparent at night because as I lay down my throat would close up.

Luckily for me I came across an interview between Dan Neuffer (CFS Unravelled) and Brenten – who had tremendous difficulties with tolerating food and had to change what he ate every few weeks because his body wouldn’t tolerate it anymore. I hadn’t come across anyone like that (like me) before.

I remember in my hazy memory, that Dan had asked Brenten ‘Are you really resting?’ That struck a chord with me and so in my late night, drowsy state I thought to myself you HAVE to calm down and get better sleep.

So, I just pretended to myself that my life was fine and shut out anything and anybody, as far as humanly possible, that contradicted that view. I ‘knew’ it wasn’t the truth but that didn’t matter. In my little fantasy world I calmed down enough to sleep better and woke up feeling just a little bit different – in a good way. I tried the olive oil and no throat swelling. I couldn’t even begin to explain the science behind that but that is what happened.

Since then – probably April 2019 – I’ve continued to build on that initial shift. The more empowered and calmer I feel, the better I sleep, the wider variety (not that wide!) of food I can eat, without too much of a reaction.

Over the years and particularly from 2016-2019 I was on a fairly precipitous downward trajectory in terms of all aspects of my health. Since April 2019, I seem to be working my way back up the side of the ravine. For me my stress response, sleep, food intolerances, inflammation are all intertwined – one sets off the other – either negatively or positively. I’m aware that chronic inflammation is not good for my health but I have regained most of my capabilities.

I might be a bit slower in thinking about things and I’m aware I can’t multi-task too well and my organisational skills are a bit rusty but I can do most of the things I want to if I pace myself, rest if I need to etc. And I find that encouraging. I work at all of this every day and pick up new tips all the time from Health Rising and the many generous people who share their wisdom and experience online for others to make use of 🙂

@Tracey Anne, it is sooooo sad about Yasmine. She was a great pioneer and advocate for us with MCAS.

I have found that actually adding histamine at the right time is of benefit with MCAS. Trying to get the Histamine 2 receptor to trigger and it not be done by an over response of my own histamine. There is actual science to prove this out. But getting it to work properly is a real trick and timing is crucial. There are several blogs on the Forum you can look into with listed articles of the science. I’m no longer on antihistamines and doing most with diet and a few crucial supplements. If I don’t get on top of my own body responses fast enough, I use GastroCrom. But seldom need that any more. I have daily occurrence with mast cell responses. But know what the signs are and can tame them faster before they get out of hand.

I do believe in letting food be our medicine. But it can also be our poison. Too much, is well toooooooo much. We have to be more aware of what things do to us and our body gives us those clues if we can pay close enough attention.

Yes, I was thinking about you, Issie and your experiences with histamine – our bodies are just so complex and finely tuned. I think there’s more awareness now that the Goldilocks phenomenon of just enough but not too much is applicable. And dejurgen too – I am paying attention dejurgen but I am completely out of my depth with your intricate explanations. Actually what compelled me to write today, was your words dejurgen – ‘a very frequent but lower level (over) activation of mast cells. I can almost set my clock on them for coming in after eating food.’

I use a mixture of the science that I understand, ideas I pick up from others and a constant monitoring of my lived experience to sort of orchestrate myself through each day! I feel a bit of winging it – is rather overly relied on…

For once I’ll give the simplified version of Issies very deep histamine knowledge ?:

* Histamine in our bodies is not wrong, it’s an essential chemical in our bodies.

* When histamine levels in the body are quite low, they are actually too low. When histamine in the blood is too low, mast cells more easily degranulate to release new histamine into the blood stream.

* When mast cells are triggered to release histamine, they however often do it in bulk and release a too strong cascade of it. That’s bad MCAS.

* As histamine is slowly made and stored in mast cells and other specialized cells for quick release when needed, it takes time to replenish stores after a massive histamine release.

* When rebuilding their stores, they release few histamine. Few histamine however sets their trigger point for massive simultanious histamine lower again…

=> So many MCAS people have IMO alternating too low and too high (after an MCAS event like eating food or exercising) histamine levels.

Uping histamine by food or drinks a bit *when histamine blood levels are too low* therefore has the potential to desensitise us (and our gut even better). Uping histamine during a dump only makes things worse.

=> So it seems to be about trying to more level out histamine levels (in an IMO fairly large subgroup that is!).

IMO the same could be said about food seratonin. Nettle tea contains both. I have benefit drinking some “when not well fed” and half to full an hour before the main meal of the day. Issie experiences benefit of it drinking it before sleep. That could be because some seratonin *might* convert to melatonin.

When using nettle tea, don’t use nettles in seed. Many warn the seeds could get stuck in tissue creating inflammation if they end up in your drink. I couldn’t check that claim.

Stinging nettle tea is in natural health mids said to help against hay fever a bit too during the season.

Have you tried to use the “bed of needles” with gentle pressure on your belly (after eating) yet? I love it.

See https://www.healthrising.org/forums/threads/a-bed-of-nails-for-better-sleep-acupressure-mats-fibromyalgia-and-chronic-fatigue-syndrome.5221/#post-37334

Sounds a lot like DNRS!

Hi Tracey Anne,

“The more empowered and calmer I feel, the better I sleep, the wider variety (not that wide!) of food I can eat, without too much of a reaction.”

=> Issie and I both experienced that poor sleep sets our mast cells to more easily activate the following day. There are actually studies confirming that. When we (IBS subtypes) get easy MCAS after food, it only gets worse after poor sleep.

“– I am paying attention dejurgen but I am completely out of my depth with your intricate explanations.”

I know, science is unfortunately very complex. I try and simplify things, but getting a grasp myself is a huge challenge already.

“Actually what compelled me to write today, was your words…”

I hoped they would trigger someone to write about their similar experiences. Another person relating to these complex ideas says more then a thousand words for most readers. Thanks for doing it so readable Tracey Anne ?.

Thanks dejurgen 🙂 and…

a) Will look into the bed of nails/acupressure mat – I wonder what it’s doing – actually even as I think about it, I’m breathing deeper – weird or what!

b) Love the ‘simplified version’ of Issie’s histamine info – that’s about my level…

c) Will investigate nettle tea – I’m over-run by them. I wonder if it makes a difference what time of the year they’re picked?

Spring is best. Then they don’t have many seeds and are said to be “more youthful and potent”. In autumn remove all parts with even a bit of seeds on it. Look for them between the leaf and the stem too.

You can dry them too. Just spread them out well in good dry air. You don’t want them to become molded. You’ll need a bit more of them when they are dried.

For anyone who isn’t sure how they look or how they should be used: buy them in tea bags with individual servings. They’re cheap and of good quality. Don’t use more then once or twice a day or as per label. Any herbal infusion can be more potent then what us weakened patients can tolerate.

“Will look into the bed of nails/acupressure mat – I wonder what it’s doing –”

For me, it sort of distracts my mind that much that I can’t think and as such breaks and interupts my thoughts. That’s a hard thing to achieve for me. It also relaxes my gut so much.

Dejurgen is trying to answer where he can for me. We are out of power until sometime next week because of the hurricane. So I don’t have wifi and not much data on my phone.

I also find a combination of Bee Propolis/Bee Pollen/Royal Jelly to be one of my best MCAS go to. Nettle tea is best for me right before bed as Dejurgen said.

A hurricane and no power – that’s no fun. Sorry to hear that Issie. Take care.

I’ve suffered 31 years severe at the beginning then medium and then 5 years ago a very severe worsening. I suffer a lot of fever like symptoms and pain, but there’s no way I approve of inflicting this vile disease on an innocent animal.

I think it’s cheating science using living conscious beings and making them suffer. What’s concerning is most lab animals suffer far worse than we ever are. They are forced massive drug dosages to the point of poisoning to death. As done in the LD50 test. (Look that up)

Anyway “Necessity is the mother of invention” Meaning device’s like the nano needle, lung a chip, and other human organs on the similar chips exist because good researchers know that animal models aren’t very accurate.

Interestingly there’s a full human organ system now on these chips. Wouldn’t that be better to create an ME/CFS model on than inflicting suffering on an innocent soul like an animal.

I’d sooner lay here suffering than have anything to do with the hurting of the innocent

Who’s doing this animal research? because I’ve been donating for years a don’t want my money going to scientists that cheat by inflicting cruelty on others. Especially when there’s already alternatives

Very good point, I was hoping ME/CFS was going to be a disease that didn’t go down the unpredictable route of animal research. As so much failure with animal models, and too much suffering.

‘Cheating science‘ is an interesting concept, I’ve thought about this when the Nazis did cruel scientific studies on adults and children. I saw those human experiments as a hijacking of science. You are right the same concept applies to animals.

Like humans they are conscious too, it is still consciousness that is suffering no matter the species, I see they often don’t give pain relief or sedate animals in scientific studies because the medication can alter results.

Anyway like you say there are alternatives in existence. A human model that isn’t conscious seems a far better idea

There are a couple of worthwhile areas to consider. Firstly- with all of these things the issue of cause and effect is significant. In the case of autoimmunity there is often a prior injury that triggers CSF leakage and interaction with the brain. So autoimmunity may be a factor maintaining the problem but not a primary cause of the problem.

Your recent article on the parabrachial nucleus is significant and i would draw your attention to this osteopath’s talk on the issue o craniocervical instability. He highlights that the result of torsion on C2/3 is a twist in the dura between C2/3 and the tentorial membrane, and that this can have a direct effect on the blood flow to areas in the brain stem – such as the PBN, -but obviously in a highly anatomically individualised way.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JyzOlUN3pBk&t=35s

Now this mechanism could explain sudden deterioration into CSF/FM following infection in a way that autoantibodies could not (onset of autoantibodies would be a later phenomenon).

I just read your article. I have seropositive AAG. I think my level was a .56. I have had many different symptoms that come and go over the years but the hardest problems is getting tested. I was a nurse for over 20 years and never heard of anything like this. I worked closely with doctors who only seem to know POTS but nothing about AAG and cant find any here that even believe me when I tell them that i have it because I LOOK too good to be this sick. Worse thing is that i think my older kids have it and no one will even test them. Hopefully long covid will open some eyes and get results. I was origionally diagnosed with fibro because they couldnt find anything else till i accidently found someone who had specialized in dysautonomia but now he moved and we are stranded with Drs who think we are not really sick and dont know what to do with us. I think mine was triggered with childbirth then walking pneumonia over 30 years ago. It came and went on spells, now after menopause it wont let up.