The NIH recently found a way to kick the chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS) community in the teeth again. Jack Reacher couldn’t have done it any better. You have to give it to the NIH: they’re nothing if not masters of disappointment.

Francis Collins promised a long-neglected ME/CFS community that the NIH would finally get serious about the disease. He was wrong.

Almost five years ago the NIH – largely in response to the Institute of Medicine (IOM) report – funded its first ME/CFS research centers in over 15 years, and started on an in-depth intramural study under the direction of Avindra Nath.

It seemed like the NIH was indeed turning over a new leaf. Director Collins actually agreed that the disease had not gotten enough research and challenged the ME/CFS community to “watch us” and “Give us a chance to prove we’re serious, because we are”.

Not Great but Not Embarrassing Either

“Given the seriousness of the condition, I don’t think we have focused enough of our attention on this.” Francis Collins

Looking under the hood, the news was good and not so good. While it was great to see the NIH finally pro-actively funding ME/CFS, the Centers project fit a kind of NIH meme evinced by then Director of the Office of Research on Women’s Health Director, Vivian Pinn MD back in 2006 when she stated – in reference to the last NIH-funded ME/CFS grant – that the NIH did just enough not to make it “embarrassing”.

(We wouldn’t even be talking about ME/CFS research centers if Vivian Pinn hadn’t stepped in to rescue ME/CFS after Anthony Fauci cast it out of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) in the early 2000s. NIH funding of ME/CFS fell to almost unbelievable depths but ME/CFS’s federal advisory group, CFSAC, remained, and it was that group that got the Institute of Medicine report funded, which then laid the way for Research Centers and intramural project.)

The research centers were a step forward but only that. Researchers reported that they were burdened with so many reporting requirements and received so little money yearly ($1,200,000) that some didn’t apply. Many, though, were so eager to get any money for ME/CFS that ten did, and three research centers were funded for five years. Whatever their limitations, though, the centers still provided a few ME/CFS researchers the rare opportunity to engage in large, complex, and expensive studies.

NIH Doesn’t Get the Memo

“Give us a chance to prove we’re serious – because we are.” Francis Collins, NIH Director

Three years later another singular event occurred – the coronavirus pandemic – that changed everything, it seems, except the NIH’s attitude towards ME/CFS. The near-identical symptoms, the exercise, gut, autonomic nervous system, etc. results all indicate that the predominant form of long COVID is essentially what we know of as chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS).

- Check out a superb New York Times article “How Long COVID Exhausts the Body” which mentions the ME/CFS connections.

So far as NIH funders were concerned, the striking long-COVID ME/CFS connection might never have happened.

Nobody could miss that connection – not the public, not doctors, and certainly not the researchers or bureaucrats in charge of NIH funding. There’s no escaping the central fact that ME/CFS is inextricably linked to what’s been described as one of the most serious health threats of our time. There’s also no escaping the fact that ME/CFS’s credibility is on the rise.

Apparently, the NIH didn’t get the memo. Four days ago, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) announced that the next iteration of NIH-funded ME/CFS research centers would be getting the same crummy funding as the last iteration. Instead of the 20 or so research centers that ME Action noted that National Institute of Neurological Diseases and Disorders (NINDS) Director Koroshetz acknowledged – prior to the coronavirus pandemic – that ME/CFS needs, the ME/CFS community would remain stuck with three small ones.

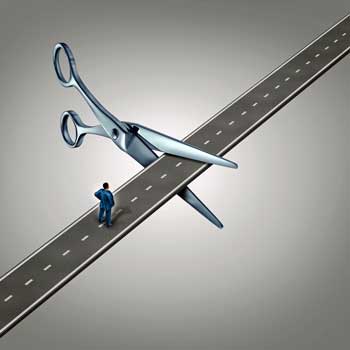

The funding makes it clear that NIH either never intended the 2017 funding to provide a glide-path for significant new funding or if it did, it quickly forgot about it. With only five institutes supporting the second research center package, compared to nine in the 2017 package, the NIH has become less supportive of ME/CFS over time, not more. It’s clear, now, that the 2017 funding was in response to a singular event – the publication of the IOM report – and once the impact of that event dissipated, the NIH’s interest dissipated as well.

Time Warp

Hearing that was like stepping into a time warp in which no pandemic had occurred, no link to a major health threat had been established, and ME/CFS remained a kind of strange stepchild that no one wanted to adopt. The unwillingness to substantially increase ME/CFS funding was doubly confusing given that the NIH prominently stated on their RecoverCOVID website that they hoped that the long-COVID research would provide insights into ME/CFS.

What the NIH didn’t say is that it expected those insights to kind of magically morph through the ether or metaphysically translate themselves into ME/CFS findings. It certainly wasn’t going to help. (Somebody on the RecoverCOVID website apparently got a little too enthusiastic about supporting ME/CFS, by the way. The wording supporting ME/CFS has been scrubbed from the website.)

For me, I was so darn naive that it’s embarrassing now to even think about it. When, with a wave of its pestilential hand the coronavirus had laid bare for all to see that post-viral illnesses could be devastating, that they affected young, healthy people, and that the biological abnormalities were there for the looking, I thought that would mean something to the NIH.

After all, the medical profession, by and large, seemed to turn on a dime and publicly quickly agreed that long COVID was real, that it was serious, that it was clearly linked to ME/CFS, and that it needed a lot of funding. Countries all over the world started following long-COVID cohorts with the result that long-COVID research – still in its infancy – already far outstrips ME/CFS/FM research.

The NIH Misses Out

I didn’t take into account, though, that the biggest medical funder in the world – our own NIH – was the odd man out. As the rest of the world sprang into action, the NIH sat on the fence and funded few long-COVID studies. In retrospect, the fact that the only thing we heard from the NIH was Francis Collins’ blog hailing long-COVID patient-supported studies (but not NIH-funded ones) should have been a big red flag.

The NIH’s strange approach to ME/CFS – highlighting its enormous needs while refusing to do anything meaningful about them – means it can’t be trusted with this disease.

In retrospect, the NIH’s ability to virtually ignore one of the top medical topics of the day was an indication that the old power structures, the special interest groups (read the big, well-funded diseases) were probably fully in charge – and they weren’t having any of this long-COVID stuff. It wasn’t until Congress – in the form of a $1.15 billion check – stated they wanted long COVID studied that the NIH did anything.

Still, I thought the opening long COVID offered for the NIH to redress past wrongs might hold sway. One could persuasively argue, after all, that it was the NIH’s neglect of ME/CFS that had left people with long COVID so high and dry. Plus, there were those 865,000 – 2 million sick people with ME/CFS, who, time and time again were told, when they went to the NIH for help, no thanks – you’re on your own. Surely, the advent of long COVID had activated some pangs of conscience and triggered at least a grudging recognition of some historical wrongs.

With ME/CFS being clearly linked to long COVID, and with the NIH’s coffers full after six years of significant budget increases, it seemed to me that the NIH had all the reasons (and the cover it needed) to do an about-face, make some amends, and provide some real funding. Not a lot by the way – not by the NIH’s standards. A small amount of funding – $20-30 million a year more – would probably have been sufficient for the funding-starved ME/CFS community.

The NIH, after all, wasn’t hiding anything about ME/CFS. It powerfully displayed the needs of this field in its Research Centers grant offering:

“ME/CFS is a debilitating and complex disorder that severely impacts the lives of an estimated 800,000 to 2 million Americans, with 25% or more of the individuals either house- or bed-bound. The underlying etiology and pathophysiology of ME/CFS are unknown, there is no diagnostic test for the disease, and there are no FDA-approved treatments for ME/CFS.”

In its description of a common, almost uniquely debilitating disease with no known etiology, diagnostic test, or FDA-approved treatments, the NIH clearly and succinctly acknowledged the needs present – then dismissed them with its ridiculously low funding. It fully knew, in other words, what it was doing.

Hollowing Out of Key Study

The most potentially important study in ME/CFS’s history was stopped well short of its intended goal.

Given the NIH’s recent actions, the hollowing out of the NIH’s intramural ME/CFS research study is of greater significance. The study was truly the cream of the crop of the 2017 funding. Even if the research center studies failed, this impeccably conceived and organized study seemed, except for its very small size, like a cannot-fail project. The most potentially impactful study in the history of ME/CFS, the intramural study essentially constituted a contract with the ME/CFS community. If the study found something, the NIH was bound to follow it up with real money.

Then the study ran into the coronavirus pandemic. Avindra Nath’s decision to curtail the study early and assess its findings was understandable but unfortunate, and potentially, given NIH’s continued hands-off stance towards ME/CFS, devastating. We don’t know what the truncated study will show, but we do know we won’t have the full findings – findings that were supposed to build the backbone of a new and expanded NIH-funded ME/CFS program.

Given the small size of the study, those findings always seemed a bit tenuous (Nath argued they were not), but with the study severely truncated, they will likely have much less impact. With the NIH clearly not embracing ME/CFS, the study’s small size will give it room, if it chooses to, to dismiss them. At the very least, the shortened study could set us back years.

Ironically, long COVID – the beneficiary of the original ME/CFS study – will have those findings, but the small ME/CFS field won’t. Nath has said that he expects the long-COVID findings to apply to ME/CFS, and they surely will, but the ME/CFS field needs to have the resources to validate them in ME/CFS, and given the NIH’s business as usual approach, doing so won’t be easy.

A Consequential Blockade

All of this might not be so bad, and in fact, might not have been that big of a deal if the NIH had just consented to include people with ME/CFS in its long-COVID studies. In possibly the most consequential decision the NIH has ever made about ME/CFS, the NIH decided not to allow ME/CFS patients to participate in the hundreds of Congressionally-funded long-COVID studies it will surely be funding.

Preventing ME/CFS patients from taking part in the Congressionally funded long-COVID studies – and then not providing any relief for that – underscores the NIH’s antipathy towards ME/CFS.

Had the NIH decided otherwise, we would have quickly been able to learn what applies to long COVID and ME/CFS, ME/CFS would have been at the head of the treatment studies, etc. Instead, the tiny ME/CFS field is left trying to digest and methodically assess, and then test, the enormous amount of data that’s sure to come from the long-COVID research. That’s far too much for a little field to do on its own in any reasonable amount of time.

That the NIH hasn’t found a find a way to rectify this problem or find a way to support ME/CFS in its effort to do so is just astonishing. Of course, it’s possible that Vicki Whittemore and company will, against all odds, pull off a miracle and convince the NIH to do that. Clearly, nobody should hold their breath.

Illusions Gone – Clarity Reigns

“The field “desperately needs some new ideas.” Francis Collins, NIH Director

All this points to a real naivete on my part – an incredible naivete, really, given the long, long string of disappointments I’ve witnessed over the past thirty years with the NIH. Even after all that, for some reason I expected the leopard to change its spots. This is the single biggest disappointment I can remember in all these years.

There is a silver lining, though, and it’s called clarity. If the NIH couldn’t support ME/CFS research now – when all the stars seemed aligned for it to do so – it’s not going to do so any time soon. The NIH has shown a remarkable ability to shake off damning reports, cries for help, and pleas from very, very upset people. It’s shown that it’s immune to calls for well-considered and thoughtful calls for fairness, equity, or ethical treatment.

As small as the NIH-funded research center package was, it was a start. Now we know that for all the big words – for all Francis Collins’s seemingly heartfelt promises – that the NIH would eventually revert to its mean. This is the shattering fact – that even a global pandemic of long COVID, err ME/CFS patients, couldn’t get the NIH to move even a little bit on ME/CFS.

Let’s hope that Vicki Whittemore and the Trans-NIH Working Group can make some things happen, but let’s give up the idea that they will. Let’s certainly give up the idea that whatever they manage to do will be sufficient. Instead, let’s recognize that NIH is not going to “snap to” or suddenly “get it” – it just had the opportunity to do that and blew it – and therein lies the opportunity. The NIH’s actions have made one thing very, very clear: if we want results in anything resembling a reasonable time-frame, there’s only one place to go – and that’s Congress.

Forget the reports, forget trying to appeal to the NIH’s better nature, forget the well-reasoned arguments. Forget all that. There’s only one organization that can fix this mess – and that’s Congress. That’s doubly true now that the NIH may have finally made its big mistake.

The NIH’s Big Mistake

Instead of turning over a new leaf, the NIH continued on its well-worn path, and therein it may have made its big mistake. The coronavirus pandemic has changed things. Congress pledged $1.15 billion to fight long COVID. That’s not play-around money. That’s serious big-time money. Congress is not fooling around.

Has the NIH turned its back on ME/CFS one too many times?

One wonders, then, what Congress will think now that the NIH has once again turned its back on the original long haulers. These are the formerly healthy, young people who’ve been sick with a long COVID-like illness not for 6 months or a year but for decades. People who, like the long haulers, haven’t been able to find a doctor – except they’ve been looking for decades. People who’ve experienced the same abuse by the medical profession that has enraged the long haulers and their supporters – for decades. People whose careers were ruined decades ago by virtually the same illness that Congress has allocated so much more money for. People who the NIH, left to its own devices, is continuing to treat like dirt.

Hence the NIH’s big mistake. Things may not have changed at the NIH, but they have changed in Congress – and Congress is, after all, the NIH’s master. When the NIH decided to treat ME/CFS as if long COVID never happened, its bias against ME/CFS was starkly laid bare. Its unwillingness to act – even when given all the opportunity to do so – in an appropriate manner with ME/CFS clarifies how little it can be trusted with this disease or the well-being of its community.

The NIH has been derelict in its duties to the ME/CFS community for a long time, but now that dereliction is being laid bare in harsh relief. If the NIH can’t bring itself to support the original long haulers, a simple, blunt, and much-needed fix is available. Congress relieves the NIH of its role as the overseer of ME/CFS research, Congress decides how much funding is appropriate, Congress, like a parent overseeing a negligent child, oversees the NIH to ensure that it acts.

In making its distaste for this disease crystal clear, I say the NIH has actually gifted us with an enormous opportunity. In fact, it may have opened the door for more ME/CFS research than it could have possibly imagined. As we head into Advocacy month, upcoming blogs will focus on that.

- Check out ME Action’s response – The NIH Comes Up Short Again

Farcical? Yes.

Surprised? No.

I was on 23&me the last couple days. I found a gene/SNP that I am researching to see if it’s a key player in all my “mystery” junk recently. When I clicked on the SNP link in question on the 23&me site, it takes you to the NIH site. I look for the publications/study info. and see if it’s something I understand or can take to my docs. Otherwise, I’m clueless on the gene info, LOL.

The NIH site popped up with a voluntary survey. I gave some specifics but not my medical conditions. After reading this article I’m glad I gave those specifics. You never know what info might make a difference. Not sure if random survey or every visitor gets a survey…….just an FYI

Global corruption in the disease management agencies intentionally neglecting those perceived as “useless eaters”? Yes.

Same here in Western Australia. Our proteomics lab, the best in the world is focussed on Long Covid and ME/CFS is being ignored.

I just read an Australian article on long covid that didn’t even mentioned ME/CFS, which says a lot.

Hi Ted, I have just been diagnosed with Fibromyalgia, 7 years after having the first symptoms in 2015. I am interested in finding out about local resources, especially any GPs or specialists who will not just give you pills then consign you to the too hard basket. Please get in contact.

We’re going to have something to help with that soon.

As of next month, that’s March of 2022, it will be 42 years I’ve been suffering from ME/CFS. But hey, no need to rush on MY account. I’ll just patiently sit back & wait some more for the soulless creatures who run the NIH to grow a conscience in the face of my suffering. But I’m sure by now they’ve figured out that if they wait just another decade or two I will no longer be a thorn in their side. Can’t live forever, which is good for them AND for me. I can’t even fathom the depths of inhumanity necessary to ignore a community who has suffered for as long as the ME/CFS community has. And people wonder why I no longer get health screenings and regular checkups. Why would I? To prolong my life? Don’t make me laugh.

Exactly.

I was recently assigned a social worker, and she cannot get it through her head that I don’t take magic pills because there are none. She is constantly trying to con me into seeing a doctor, and I keep having to remind her that doctors have repeatedly tried to kill me. I no longer trust them.

Plus, as you say, I have no interest in prolonging my life. I’m tired of being alone and neglected and not getting the help I need.

Because even Useless Social Worker was only interested in making me see a doctor and move to a nursing home, rather than in getting me the household help that the Olmstead case says I’m entitled to so that I can continue to live at home. With reduced immunity, the germs in a nursing home would literally be the death of me.

Excellent summary of the experience of millions. How many people are catching on to the financial benefit to the “haves” by longterm marginalizing to death the fragile and vulnerable?

I know exactly what you mean. I have had this since 1966 and with age it is getting worse. I am now flushing and burning. I have been gaslighted so often through the years I had a hard time replying here. My first time.

CFS Facts,

I am really glad that I am not alone in my thoughts…I was diagnosed with CFS about 18 months ago and it has RUINED my life…and like you I feel completely alone, neglected much less getting any kind of “help”….I am sick of trying to “prove” my illness because medical professionalism and disability insurance can’t use common sense when a 43 year old marathon runner with a successful career with a salary almost 6 figure salary can barely leave the bed, do any sort of fitness let alone work? I was removed from my position from exhausting all my leave options yet I get looked at as if I am just being lazy trying to take a1/4 pay cut…It infuriates me. My employer who removed me involuntarily has the nerve to deny disability retirement after saying I need to “prove with objective evidence I can’t work?” I responded with “You fired me”…People ask-me the standard suicide questions and I always respond that I am not suicidal but wouldn’t be opposed to a bullet in my head…I feel so alone because nobody understands..For me CFS onset came sudden and hard..I was fine one day it seems and in my bed the next…I often wonder if COVD did something to make it happen or if it’s from burn pits during numerous Iraq deployments..Either way I would do anything to have my life back…because I merely exist right now.

I’ve been angry, not depressed, ANGRY. I’ve been involuntarily committed to psych hospital, (June 2021, with bloodwork showing reactivation of Epstein-Barr , low hormones, low thyroid with a nodule that we have to biopsy,) and the dr still had me committed. I never expected NIH funding, or long Covid to pave a way for us. But if I say I feel hopeless, it’s a true reflection of how I’ve been treated for 20 years.

Oh, and if you didn’t know, a psych hold consists of stripping you naked, taking away all your belongings including your phone, so not only are you helpless, you can’t contact your family for help. Nor did I receive any MEDICAL treatment, including the meds I take for heart, BP, Ulcerative colitis and epilepsy

Susan. I’m so sorry!!!!! Are you available to speak with me? I am on Twitter: @rivkatweets

Susan — that totally sucks. Are you aware that a possible treatment for chronic EBV problems can be spironolactone? There’s a paper from about 2016 showing it stops EBV replication, and a conference abstract from 2020 in Australia showing it improved ME/CFS severity in about 2/3 of people with antibody markers for EBV. It’s helped me. (NB. If you can’t get anyone to prescribe it for the EBV reactivation specifically, it is also a treatment for high BP if you have that.)

I’m so sorry you were committed with ME. You may have autoimmune encephalitis. It has psychiatric symptoms and ME symptoms and drives one crazy. You might want to test for HHV-6 antibodies from Quest laboratory. HHV6-6 is implicated in ME and thyroiditis.

I hear that, same here, plus who can afford anything else.

Quality of life is nonexistent with ME.

And who wants there family suffering through it.

That drop of hope for research has gone.

Twenty and a half years of ME/CFS here, and my greatest disappointment at this point is that it’s not terminal, since there’s no diagnostic test, no treatment, no relief, no end, and no dignity. I shake my head in frustration all the time over the thought “how do you get health screenings when you’re too sick to leave your home?” The big worry is always being forced to leave the house for a crisis such as a root canal since I can no longer participate in preventive medical care.

Your story sounds a lot like my own. I have had M.E. for over 35 years, getting this devastating disease in my mid 20’s. I am now in my 60’s, after believing for all these years that something would be done to help people like me. I had to quit working, as I never know if I will be well enough to get out of bed, so cannot be relied upon. Extreme fatigue from morning to night and at first trying to live a normal life all these years, has stolen my very soul. With all the other diseases we develop over time with M.E. such as hypothyroidism, heart disease, severe osteoporosis and osteoarthritis, orthostatic hypotension making it extremely difficult to stand in any line up, degenerative disc disease, degenerative joint disease, neuropathy, torn muscles, tendons and broken bones (I have broken 5 bones last year), food sensitivities – not eating diary or gluten for 35 years, IBS, aching joints, muscles and other pain throughout our ravaged bodies makes living very difficult indeed. There are many days when I think I would be better off leaving the world behind as there seems to be no future in which I can exist. Since the Pandemic and my weakened immune system, I have stayed home for over 2 years and am still too afraid to go out in society and possibly contact the Omicron variant, which would most likely end up with me in the ICU Ward and possible death. Even though some days death seems easier than living with this debilitating life sucking disease, I don’t want to die alone in an ICU Ward. So, I am stuck inside my body which is stuck inside my house (mental health issues are already something we have had to cope with for decades, combined with the Pandemic and the real fear of dying. It is always a war between my mind and body and when I use my mind to override my body, I pay the price big time – bedridden for up to a week if I overdo anything. When the studies came out for Long Covid, I was ecstatic thinking that maybe I could get 5 years at the end of my life where I could live even half of what my former life looked like, which is very difficult to remember. Shame on the NIH for leaving the real “long haulers” behind and not including us into their scientific studies when there are millions more of us than the Long Covid Haulers. Why do they take priority over those of us being tortured and suffering for too many years. One of the main reason for people dying from ME is through suicide. Oh yes, I have thought of that many times, but would not want to leave that legacy to my children. I struggle and suffer through each day wondering when will be my last. It will definitely be a relief to end all the lose of life and suffering indefinitely. It would also be a gift if I was given even 5 years of a healthier life, if the NIH would give us a fleeting thought. Seems like they will not and so here we go on and on with our hopes fleeting away when we read articles like this. We are told to endure to the end but enduring is not living!

Very well said!!

Good article, but let’s please not further stigmatize other medical illnesses that have been stigmatized even more than ME/CFS with the “schizophrenic approach” language. If healthcare professionals or anyone had any awareness, they would know if CoVid longhaulers existed not so long ago, that they would be getting ice picks through their orbital sockets just like individuals with Schizophrenia AND ME/CFS used to!

Just following up to my post- Most individuals who use such language have no ill will, but just lack of awareness. The point is, is that that lack of awareness is a main underlying cause of the lack of research for FM/ME/CFS. I am an individual with 35 years lived experience of such illnesses and of the medical neglect that comes along with them. I have awareness that if I was born a couple decades before I was, that I could have had an ice pick severing my brain, instead of the more “modernized” version of ECT’s, and other psychiatrization that I experienced. I am a professional doing the exact same advocacy and legislative work as the author, so I felt it necessary to comment. May we make strides for our shared goals!

I understand your point. I used schizophrenic because it’s such a powerful term. I don’t know any other term that so evocatively portrays the “contradictory and inconstant” approach taken by the NIH towards ME/CFS. (A “contradictory and inconstant approach” to something is how the term schizophrenic is defined when it’s used way it was used in the blog. )

I could use “contradictory” or something like that which doesn’t pack nearly the punch that “schizophrenic” does – and therein lies the dilemma.

I’ll figure out something and change the wording

There is no illness with such hopeless, endless, untreatable, debilitating 24/7 lifelong cruel symptoms as high moderate to severe ME. It is recognised as having one of the lowest qualities of life of any illness.

I believe that is true.

And no one gives a dang because according to the medical field and lack of research directly influences the belief that it no big deal.

I take showers in case I am found dead!

¿Por que hacen esto?

¿Por que nos ignoran?

¿Que hemos hecho para no sólo sufrir de esta enfermedad devastadora sino para además sufrir el menosprecio de nuestros dirigentes?

Nos encerraron en una cárcel y tiraron la llave.

Bueno, soy un investigador de la area de la salud de más de 15 años de experiencia que investigó por años sobre ME/CFS. Tengo leads y comienzo a creer crescentemente que sea intencional – que CFS fue creado, y tal vez sea una trampa hecha en el ADN humano a través del CRISPR-Cas9 – es decir que para llegar a la cura debemos descobrir cualquier parte del ADN que pueda haber sido alterado y cambiarlo igualmente con la tecnología del CRIPR-Cas9. Es todo muy, muy sospechoso lo que estudié sobre ME.

Thank you , Cort, for your heartfelt and honest look at the hopes you had for any real help from the NIH, and your realization that our only way forward is through Congress. As you say, their turning their backs on us, again, may be the very thing that moves us forward. Insanity, as it’s said, is trying the same thing over and over and getting the same results. Now we see with clear eyes what has to be done. As we let go of any expectations from the NIH, we can concentrate our efforts where the real help will come from.

The good news is that Congress can actually make a difference. It was Congress that provided the NIH with $1.15 billion dollars. It’s Congress that is responsible for the vast majority of the “NIH initiatives” like the 21st Century Cures, the HEAL initiative, and many others.

I remember a blog about 10 years ago that said at one point in the 1990’s after extensive lobbying by CFS/ME sympathizers, Congress earmarked funds specifically for research in CFS/ME. But it was thwarted by whomever controlled the NIH department that oversaw the disease at the time. Seems to me the blog said the guy allocated the funds to another program. Nothing ever happened to him for his blatant disregard of the law. I thought I read that on this blog but I may be wrong. At any rate, apparently nothing ever changes at NIH.

Things get muddled over time. That episode actually did us a ton of good. Congress was actually quite concerned about ME/CFS or CFS as it was known and appropriated 22 million in the late 1990’s to the CDC (the lead agency investigating ME/CFS at the time) to study ME/CFS. That was a lot of money back then – actually more, accounting for inflation, than the NIH is spending now on ME/CFS. The CDC diverted about from $9-10 million of it to other uses. Bill Reeves, then head of the CDC program for ME/CFS, evoked the whistleblower act, an audit was done, and Reeves was vindicated. Reeves superior, Brian Mahy, was replaced, and the money was restored.

https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/politics/1999/08/06/retaliation-alleged-at-cdc/c3ea5fdd-fc7f-4cd1-8dbf-c42e76f75c7f/

https://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-srv/national/daily/may99/cdc0528.htm#:~:text=In%20his%20report%20to%20Congress%2C%20Reeves%20said%20that,syndrome%20laboratory%20work–even%20though%20it%20was%20not%20true.

https://www.science.org/content/article/controversy-claims-cdc-lab-chief

The CDC also funded its first public relations campaign on behalf of a disease, a group to assess ME/CFS grants by themselves, and maybe even the creation of CFSAC may have all been reactions to the CDC scandal. They all took place around that time.

Cort, Are any advocacy groups putting together proposed legislation that would compel NIH to fund ME/CFS research? This seems to be the what we need. If not, I would willing draft something and would like to get this going.

Oh yes… We’ll learn about those shortly!

Yes, Congress can make a difference, but will they? Has each and every one in Congress been made aware that the NIH and CDC are doing too little to bring us ample researchers to tackle ME/CFS? So many of us are like me, too ill to reach out and follow up with every member of Congress. I’ve tried contacting my members of Congress about us, but I’ve never heard back from them. After 29 years of ME/CFS and having Long-Covid since March of 2020, just responding to you right now is killing me.

Yes, they are Donna. Solve ME in its legislative work has been educating legislators about the big divide for years and ME Action until a couple of years ago was doing the same thing.

They are better educated than ever – which is why I am hopeful.

En mi caso, era SFC/EM desde 2008 y ahora en 2020 después de pasar Covid19 mi empeoramiento es tremendo. Algunos me dicen que mi empeoramiento se debe a SFC, seguramente para no ahondar en mi tratamiento y seguir arreglándomelas yo sola. En el caso de mis síntomas de poscovid, tampoco tengo ningún tipo de ayuda, con lo que tal y como dice el artículo, sigo estando sola.

Two suggestions: 1) consider rewriting this as a letter to the next NIH Director. That nomination should be announced soon, and it would be good for that person to hear from us before he/she enters Building 1.

2) You can re-frame your point about the “original long haulers.” I know you are using that to describe people living with ME/CFS for decades, but it’s coming up in other contexts now. The RECOVER protocols specificy a having had a COVID infection within the past 24 months and in some cases 12 months. That’s going to exclude many first-wavers (like me). So, two sets of “original” long haulers are being left out, at least for now.

Thanks, MIchael – I very much appreciate your advice, particularly given your experience and I will fashion a letter to the new director when he/she shows up. I count Francis Collins as a significant win – he was the first NIH to publicly support ME/CFS – and got the research centers and intramural study going.

The research centers provide a superb opportunity to do really complex, cutting edge work – look at Maureen Hanson’s work to compare the gene expression of like cells – which appears to be paying off handsomely.

We would have never seen that without the NIH funding her work. Ditto with Avindra Nath’s Intramural study. That is the promise of the NIH – which is why we cannot give up – we must keep pressing forward – and I think Congress is ready for us. We’ve linked ME/CFS and long COVID together well enough for proposals that either focus on ME/CFS or focus on the two together can work.

Unfortunately they were not linked together in the Congressional appropriation.

I think we should start a reparations campaign. Petition Congress for reparations for ME. And the reparations can come in the form of research dollars.

Wonderful idea!! Reparations are certainly owed. Would love to think the my pain and suffering for 30 years could lead to research dollars!

Rivka – fighting for reparations is the way to go, and I have been thinking that for a long time (in fact, it’s been a revenge fantasy of mine). It’s the most fitting and just way to compensate for all kinds of chronic violence against us by the government. But, as a former PR professional – and I’ve been saying this for years – we need a “celebrity” spokesperson to get noticed. We need a shame campaign because, sadly, it’s the only effective way.

Individuals need reparations too including #DemolishDisabledPoverty.

With all due respect, Rivka, and appreciation for all that you do and the cost that you pay, people with severe and very severe ME and people living in poverty are not being represented enough.

I live near you and grew up and was educated mostly in this area (and also in an out of state college). I also had a mono (and strep) onset, mine in 1983 when I was 17. I also had a significant second event, mine was at age 24 with chicken pox. I used to go to a doctor’s office that you go to but once I lost my private insurance that was the end of that and no one else has any understanding of what ME is. I used to shop where you shop when I could still drive.

I have been bedridden since 2007, have no medical care, dental care, eye care and fear homelessness in my future. I am crashed from reaching out to a local doctor’s office last year who wouldn’t help me at all and am so sick now that I believe I weight under 90 lbs. after more setbacks over the winter. I just ordered a scale but no one has unpacked it for me yet. I’ve never been this thin and I have been down to 93 lbs. before and I was heavier than I am now. I’m not even vaccinated yet as I initially didn’t qualify for a home visit(!) and now I fear a vaccination in my condition if I even can get a home vaccination now.

There is no help for me. I live in poverty. Furthermore, my benefits just got messed up because I didn’t get the paperwork in on time. Hopefully, it will straighten out. My health and life has been destroyed and I am traumatized!

People with ME deserve reparations and justice as much as research! This shouldn’t be an either or thing, it’s both!!! Moreover, publicity about both personal and research reparations is also helpful.

Lastly, I’ve never seen this addressed anywhere, but maybe you can amplify the message that homebound people are discriminated against by only being able to use their food stamp benefits to shop online at Amazon (which largely sells in bulk) or Walmart, as the politicians can’t get it together so that we can shop at other online stores or at all the stores who would take our benefits if we could walk inside.

Thank you.

And thank you, Cort, for writing this blog. I hope we can get some action from Congress in May.

Those in longterm poverty from lack of appropriate care deserve the most help, immediate help, in the form of financial reparations.

When one’s entire life has been stolen by intentional neglect and abuses by selfish bureaucrats and disease management authorities, taking action for reparations is totally justified.

This is beautifully stated, Cort. It helps me to clarify the rage I feel about all of this. Thank you so much! I look forward to being part of the advocacy work.

🙂 The good news is that with Solve ME and ME Action we are better situated with regards to advocacy than ever before. We have more allies, long COVID has brought us more visibility, we have a professional lobbying group, and we have more partners on the Hill.

We came pretty close, I believe, to passing a bill a couple of years ago (HR 7057, I think it was) that would have given Congress oversight over ME/CFS. Now we have more ammunition.

Who is the professional lobbying group?

It shows once again that the elites are in control. They control the dialog, the funding and even desire to control reality. With this top down structure, we are simply disregarded unless we can offer these “people” something of monentary value. I hate to be political about it but that’s exactly what is ruling this world. We need a new batch of leaders. Ones who are compassionate and not possessed by the desire for money and power.

So far as I can tell from my perch on the outside, the NIH is actually structured – probably inadvertently – to reward diseases that are in, and to keep diseases that are out, from climbing the ladder. It doesn’t have a way to correct itself. The cost of that are diseases like ME/CFS and fibromyalgia which despite the fact that they affect millions of people, they receive, decade after decade, very, very low funding.

The NIH can certainly point to all the good it does but it also has a very dark side – the disenfranchisement of a lot of sick people as well – many of whom are women with pain and fatigue-producing diseases that don’t fit the mold.

The NIH just seems incapable of effectively dealing with this group.

Thank you, Cort, for this very rich, and extremely well-written piece. (I just hope the effort doesn’t leave you with PEM). I could not agree with you more, and you’ve pulled together a lot of material that can enable others — advocacy groups and individuals — to lobby Congress. Hopefully we will now as May approaches. Your bringing together all this material certainly supports that.

I am still burned, though, by the actions of the CDC back in the l990s when Congress *did* come through (if only $8MM) with funding for CFS.

The “deep state” in the health areas of our government, seems to feel entitled to have a mind of its own.

How can we also try to get major support from the private sector? I am continually impressed by the work of the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation, in the late ’80s, which was helped enormously by a $20MM gift from, as I recall, Bill Gates Sr., to pursue research into a cure/treatment for CF. My facts might be a little fuzzy, but I read about it in a New Yorker article from, I think, around 1996.

The CFF has made enormous progress for its patients, despite the fact that its population is even smaller – I think about 30,000, though it is growing due to the longer life spans now of people born with CF due to the incredible work of the CFF.

Thanks for sharing this important history. Can you help remind what did the CDC do in the 90s?

On the brighter side, I think the Unger work from the CDC this past week was very consequential. In fact the finding of widespread hypocapnia in ME/CFS patients speaks directly to the breathing irregularities known and emphasized in long Covid.

@viyer05: CDC redirected the funds to research on an illness they felt more “deserving”; possibly to AIDS. The CFS groups made a ruckus when they found out – I don’t know the exact timeline – and the CDC was forced to “reimburse” the funds somehow (I don’t recall how), but only in dribbles over a few years. This is covered in some of the books about CFS in the early 2000s. I’m sure someone else on this blog is better on the exact facts but that’s the general outline.

Seems ME/CFS advocacy groups haven’t done politics as well as may be needed . The successful disease advocacy groups tend to project happy positive images of patients and their families, which can appeal across the political spectrum. The ME/CFS groups tend to emphasize the suffering and the grievance; and seem to me slanted towards one end of the US political spectrum.

Definitely Congress is where the big money is. I think the key is to emphasize ME is a population that can benefit LC research: any progressive biomarkers in LC will appear magnified in ME, and there are patients ready to volunteer for riskier treatments that can later benefit LC.

The same goes for the NIH making smaller shifts within its control: the key is to emphasize the opportunity, not the restitution.

Last but not least, the private sector will be key, maybe the key. No surprise: they will also be most receptive to messages about opportunity.

@viyer05: Ditto to all your points. The case of the CF Foundation is very instructive. They got the huge seed funding from a rich businessman (who was, as I recall, interested because the disease is fatal and so awful and because the appeal to him was based on a theory that might result in a breakthrough). The theory did in fact result in a breakthrough, and the CFF sold the patent several years down the road for a ton of money, etc. I have a young family member with CF otherwise I probably wouldn’t be aware of all this, but I find the story extremely inspiring (and the Foundation’s work continues to be). If you’re good at finding things on the internet, it’s worth looking up the New Yorker article. I think it was in the mid-1990s, probably l996.

if long covid is different from me/cfs, researchers need me/cfs data to prove it.

the name long covid saves insurance companies much money–because it REQUIRES having had covid.

so even if there are bio-markers that MATCH me/cfs, me/cfs -ers are left out in the cold.

Long covid needs its name changed NOW. We don’t need to be ‘separated’ from current studies, because of the name long-covid!

Because there is ALREADY illness that is ‘post-viral illness’ that long covid can fit under, as would many me/cfs patients.

—and there are almost always some proportion of “atypical” patients under any disease classification–so not all viral

— or are they all viral related and we just don’t know it yet because of extreme lack of funding

I’m looking forward to reading about how we can advocate Congress for additional funding. Sitting with rage without having a way forward isn’t good for anyone.

Agreed. I was up in the middle of the night unable to sleep I was so agitated by the NIH’s decision to keep to the status quo. That didn’t help!

On the other hand, their actions also ironically, open the possibility of getting real action done.

You don’t have long to wait – Advocacy month and an interview with Emily Taylor – who has spearheaded action at the legislative level – is coming up

https://www.healthrising.org/blog/2021/02/27/long-covid-chronic-fatigue-syndrom-taylor/

“The $100 million for rapid diagnostics Solve M.E. had pushed for was there – and in much the same language – and so was another billion dollars for long-COVID research. Where had that come from? Emily reports that it came down to an ME/CFS-friendly Senator with influence. They know who it is but cannot share that information at this time.

The language regarding long COVID was vague. By then, Emily said she’d been tracking different versions of the bill for 8 months and had communicated with committee members and followed up with congressional staffers. They asked her: is this what we wanted? The answer was yes. Over a billion dollars was going to flow to long-COVID research and that meant a potential bonanza for ME/CFS and other post-infectious diseases.”

Thanks, Jason – this is one reason why I believe the NIH just decided not to spend any money on ME/CFS. The NIH said they couldn’t because the money was directed for long COVID, but Congress was clearly concerned about ME/CFS as well. I think if they wanted to they could have included ME/CFS.

That’s all we ever needed. They didn’t need to include 10,000 ME/CFS patients in their studies – just enough to be able to statistically determine what was going.

The research groups are set up, the studies are set up – including cohorts of ME/CFS patients would have been so easy. Biomarkers, treatment options- they would have all flowed naturally and easily from these studies.

Instead of that – now we have to figure out a way to come up with funding and the large enough cohorts to duplicate what the NIH is doing. It’s a huge, huge opportunity lost…..That’s why I believe that decision – far more than the poor funding for the research centers – is the most consequential decision regarding ME/CFS the NIH has ever made.

Notice, by the way, that they took down any language supporting the idea that learning about long COVID could help understand ME/CFS. It didn’t take anything to keep that language up there. That language didn’t commit any funds for ME/CFS research – and still they took it down. The rot clearly runs deep.

The CDC and NIH can ignore “ME/CFS” with confidence because patients and researchers have endorsed a chimera that can not exist.

ME is the 1955 Royal Free disease.

CFS is the 1985 Lake Tahoe Mystery Illness.

Different datasets, difference circumstances. Different evidence and clues.

ME/CFS is like trying to combine a zebra and a giraffe.

Unless one uses science and treats them like different animals, you are trying to prove the existence of a mythical creature.

May as well try and study a fairy tale rainbow unicorn.

This is why the CFSAC was dissolved. That whole thing was really just to monitor the self inflicted confusion of the “ME/CFS” community.

When the DHHS was satisfied that this community had dug itself a hole they can never get out of, there was no reason to continue the pretense of “patient engagement”

To your point, perhaps ME/CFS advocacy should have some consultations to learn from the Rare Disease funding advocates and groups: they’ve had some success (with Congress and NIH) lumping together various conditions under a single umbrella.

Maybe it’s also time for a re-brand to “long-X” syndrome.

I’ve thought – what about a Congressional hearing on the pattern of low NIH funding for a particular sort of disease: female-dominated diseases that produce fatigue, pain, and high amounts of economic distress. Diseases like fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue syndrome, migraine, and IBS that year after year get proportionately very low funding from the NIH. We’re talking tens of millions of people saddled with very difficult conditions who are getting underfunded by the biggest medical research funder in the world. Unfortunately, there is just no alternative to the NIH.

Fibromyalgia actually gets much less funding per person than ME/CFS. I think it’s between a dollar and two dollars a year.

viyer05

Agree!!!

Haven’t you people noticed that every expression from federal authorities is that nothing was ever established in “ME/CFS” except some kind of unusual fatigue?

Reinforcing in every way that the mountain of immune findings and studies in what was once called ME or CFS never led to anything conclusive.

They are capitalizing on longcovid to make it the new ME/CFS.

Put the past behind them forever

I was stunned when I saw the tiny amount of funding for ME/CFS announced by the NIH. So, even now they continue to discriminate against a whole, neglected patient community.

How insular can the NIH be? They are so out of step with the way so many more people are thinking. Can they not see that?

Thankfully as you point out Cort, Solve ME’s Advocacy month is coming up and they’re inviting people to register, to virtually meet with Congress.

If the NIH are incapable of doing their job in relation to pwME, then they will need to be supervised to fulfill their responsibilities. Congress need to know the consequences of the NIH’s inaction.

I remember watching Vicky Whittemore and Walter Koroshetz move an ME/CFS initiative to lay the groundwork for a strategic plan for ME/CFS through NINDS. It had to get past a committee and it did but that committee was made up of people from other diseases – who may very well know little about ME/CFS. I imagine those committee members may often be more senior people whose views of ME/CFS probably date back quite a ways.

I don’t know if an attempt was made to ask for more money from the Institutes but it’s pretty telling that almost half the supporters of the original Centers grant – most of whom gave very little – backed out. They decided not to provide even small amounts of money for the research centers. Thankfully, the two major institutes – NINDS and NIAID – did not. I imagine they made up the difference in funding.

I imagine that much of the NIH is not enamored with the long haulers at all. They probably see them as a new disease group that’s temporarily, at least, getting lots of funding, and are going to draw resources (researchers/money) away from their pursuits.

A more enlightened viewpoint might see the long haulers as we do: as a tremendous opportunity to learn how infections affect the body and cause ME/CFS-like conditions, autoimmune conditions, central nervous system diseases, dysautonomia, and on.

I think large institutions can easily lose sight of what their purpose is – they can just end up serving themselves.

If very large numbers of unwell US citizens are consistently not receiving the healthcare that they need (over decades!) then it doesn’t take a genius to work out that the obstacle does need to be identified and resolved. Their passive and laissez faire approach, as you’ve written before, isn’t producing results.

As you’re undoubtedly aware, the GET/CBT proponents are still trying to throw their weight around in Europe (& the UK). They’ve cast a long shadow over ME/CFS patients for too many years. Hopefully as their presence dwindles and the research field grows pwME will receive the care they so desperately deserve.

Here is some information from Solve ME and the link for registration.

Advocacy Month’s keystone events are our virtual Congressional Meetings, taking place over three days:

May 10: US House of Representatives

May 11: US House of Representatives

May 17: US Senate

It’s a great opportunity to connect with and educate your legislators, raise the issues most vital to our community, and lay the foundation for a better future for people with ME/CFS, Long Covid, and other chronic diseases. Click the link below to learn more and register!

https://solvecfs.org/advocacy/solve-m-e-advocacy-month/

of utmost importance will be the directions that Congress gives the NIH regarding funding $$$$.

we had all better realize that Congress could earmark $$$$$$$$ for cfs/me, AND the NIH can decide who gets funded!!!

guess what!!!! the NIH would find reasons to finance research leaning to psychiatrists and psychologists, anything that validated the NIH’s lack of actual support for sufferers of me/cfs

has the NIH ever faced any kind of class action suit for any reason or any disease, at any time in its history??

Hola Cort.

Dices que el Congreso es quien es verdaderamente importante pero como haréis para que los congresistas ayuden al colectivo de SFC/EM.

My son is bed ridden with ME/CFS and a family member with 35 years of working successfully in D.C. with appropriations subcommittees recommends the ME/CFS community and advocates address the House and Senate Subcommittee for Labor, Health and Human Services, Education and Related Services. They control the purse strings for the NIH through the Department of Defense’s annual budget allocation process. There are 14 House members and 18 Senate members and any member can appropriate funding for substantial budget increases for ME/CFS research with a simple passage of an Appropriations Bill. These Bills get passed all the time with little fanfare. My Senator from Florida, Rubio, is on the committee and I will be contacting him regarding this. We should all reach out to our representatives on the committee and request action on our behalf. Google the 2 subcommittee members list and take some action. If nothing else it gives me satisfaction hoping I can contribute to the cause. Feel free to reach out if there are any questions.

Boh Holtzclaw

Firstly, sorry to hear of your son’s illness and the suffering he, and, by extension, your family goes through.

WOW WOW WOW !!!!!!!

“…recommends the ME/CFS community and advocates address the House and Senate Subcommittee for Labor, Health and Human Services, Education and Related Services…

They control the purse strings for the NIH through the Department of Defense’s annual budget allocation process…

There are 14 House members and 18 Senate members and any member can appropriate funding for substantial budget increases for ME/CFS research with a simple passage of an Appropriations Bill…”

“We should all reach out to our representatives on the committee and request action on our behalf…”

“Google the 2 subcommittee members list and take some action.”

Thanks Bob! We’ll all have an opportunity to do this during Advocacy Month – which is coming up soon.

during advocacy month great—-and ‘now’is even better

allways said with long covid and ME/cfs, first see, then believe…Also with congres…I am decades ill, have seen to many promises broken.

I have just contacted my Congresswoman Barbara Lee, who is on the Budget Committee. I will see what kind of response I get. I urge everyone to do the same! Google “my Congressperson “ and go to the official website and enter your zip code to find your rep. Send them an e-mail and ask for a response.

Thanks, Charnee. You’ve prepped Barbara Lee – she’s now ready for Advocacy Month 🙂

Ich bin ein Oaklander! Me too!

Hmmmmmm, 30 years of a lack of funding for ME/CFS, the ultimate oversight of NIH is Fauci- for 30 years!!! Its time for this unelected, overpaid, bureaucrat to go!

I worked for the State of NJ as a successful grant writer…I was a whistle blower… discovered the atrocities of government. If a grant was clocked in even one minute late, it got thrown in the trash, unopened. If there was a typo, it got thrown out. There are tricks to grant writing; I was sent to DC for their tutorials on RFPs…it’s been 20 years since I got diagnosed and I’m bedridden…but I can still write!! My parents were civil rights activists and journalists and publishers…I’m ready to fight, apparently Superman can’t save me, I’m 64, but for those generations behind me, it’s worth fighting for…

Susan Frei MSW

Thank you, please do add to the ‘team’

in a definite way. Hope you can help advise, either formally or informally, the me/cfs lobby group.

or wherever asked to fit into this attempt

@Susan Frei,

As I was reading Cort’s article, someone mentioned that Congress is where the big money is–if not the NIH. As an alternative, what about some of the super wealthy who have set up philanthropic enterprises?

I have no idea where to find a ‘master list’ of donors but perhaps appealing to someone like Bill Gates might be a way to find money for our cause…

As an unrelated thought, as I watch the new about Ukraine, I do hope that things like cyber attacks towards the U.S. (which is possible) don’t further push the attention away from ME/CFS.

Keep the faith and progress will eventually be made. I’ve been in a slump and so my vagus nerve articles and report about my experiences with oxaloacetate are on the back burner.

It’s really tough, Nancy. Carol Head – former President of Solve ME -has talked about how hard it’s been to get wealthy donors, let alone large Foundations to fund ME/CFS.

The Pineapple Fund, I think it was called, did give $5 million a couple of years ago to the Open Medicine Foundation and another donor recently gave Solve ME $3million dollars – so maybe that is changing.

Hey Nancy…check out The Giving Pledge. It lists 220 of the wealthiest philanthropist around the world committed to giving a large portion of their wealth while they are (hopefully) alive. I’ve written to some but they have staff and screeners that make it a challenge to connect with plus most have their “giving” themes that they stick to. All it would take is a handful to pony up and make a huge difference for us.

Susan you are exactly what we need!

I found it discouraging when I read that Collins has now been invited to be on Biden’s

Science advisors! Not good for us…

I didn’t know that, Kat. Grim. Yes, it bodes ill for us, no doubt about that.

I disagree. Yes, it’s true that Collins and the NIH have failed to follow through on their promises but Collins is the only NIH director to ever publicly support ME/CFS and it was on his watch that the research centers and the intramural study got started. Call me naive if you want, I actually think he’s a considerable asset, that he wants to do more for ME/CFS and that he could really help out in the future if he chooses to devote some time and energy to us.

This month marks 33 years with this crap. Let us know how to help specifically.

#Lane Collins and all: SolveCFS just sent around a mailing “recruiting” people to lobby Congress virtually, and to contact SolveCFS now.

I have dreadful computer skills (came down with ME/CFS before computers were much in use) but maybe someone can put the link to that into this blog?

I feel like this article and all the comments are to negativ about this. I am pretty happy tbh that they exclude us Cfs ppl. Because Cfs has such a bad connotation and ppl still claim its just some lazy ppl who just want some benefits and secondary disease gain.

Just let them do their long covid studies and use their results. Its 100% the same disease under a different name. Let them cure long covid. So we as a hated by stander get cured by accident.

Badpack

the limiting of the disease to post covid means that the narrow definition will preclude doctors from using any benefits for me/cfs-ers.

it is more likely that the results would cause a large study to be set up to see if other viral infections cause ‘long-covid-like disease. And me/cfs-ers would be excluded, just as me/cfs-ers are currently being excluded.

The NIH is never going to do the right thing. Believing that someone is going to save us is naive.

The only thing that convinces people worldwide that we are sick, is a diagnostic test. That is what saves us.

Failure to concentrate on a diagnostic each year is the problem.

ME/CFS patients, charities, activists need to get some version of the Nanoneedle test funded, off the ground, and commercialized.

Taking our hands off that for even a second was our mistake.

It would really be great to get the nanoneedle fully funded and operating. Through no fault of anyone, it’s run into roadblocks again and has not been able to reach anything close to its potential. Let’s hope it will.

Biomarkers and diagnostic tests would have been pretty close at hand, I suspect, if the NIH had allowed ME/CFS patients to be used as a control group in its long COVID studies.

Again, can someone “paste” a link to the SolveCFS email recruiting people to lobby virtually Congress in May?

Thanks

Hi Cameron,

This link should get you to Solve ME’s Advocacy information.

https://solvecfs.org/advocacy/solve-m-e-advocacy-month/

This is not from the email as that sometimes doesn’t work.

Cort, have you been following any of the developments around the Cures 2.0 Act and the Advanced Research Projects Agency for Health? Here’s a press release with an overview: https://degette.house.gov/media-center/press-releases/degette-upton-introduce-highly-anticipated-cures-20-bill

There’s a lot of debate about whether it should be housed within NIH or outside of it, and obviously the latter would be preferable, but it would nevertheless be a huge infusion of funding into biomedical research: $6.5 billion according to the current proposal.

Given the bipartisan backing it has in the House there’s even a good chance it could actually happen this year. Perhaps the ME/CFS community should begin preparing to lobby for a piece of the pie!

Thanks Matt, I’m not up on that and look forward to checking it out. This big medical research bills provide a great opportunity for us to, as you say, finally get a piece of the pie.

chrome-distiller://8e7abfeb-c0b5-47e4-84a2-505e65e6adc1_1068eedd4b96b8e2d0aa0a9e991711b60617da957c3fbe2bfcd9f569f15c8287/?title=Register+Now+for+Advocacy+Month+2022!&url=https%3A%2F%2Fgo.solvecfs.org%2Fwebmail%2F192652%2F234547566%2F68c230ff14890fe8c7eb25d3f23d1178ea7e6a5b7285a89b48d46703a219d202

I believe this is the link for the Solve ME loving efforts coming up.

Here is the link for the solve M.E advocacy coming up in May. Please register and get involved. I participated last year and we need a lot more people. For every 1000 people who complain that nothing gets done, only 1 seems to get involved to actually do something. If that’s the case then another 30 years will go by with very little progress and we will share in that blame. The time is now, please get involved. They hold your hand through the process and it’s literally 1 hour of your time for the year.

@Roger Narendran, I appreciate your enthusiasm, but blaming people who can barely brush their teeth for not being involved in yet another advocacy day is a mistake.

I am assuming only Americans can get involved with this? I receive the emails and assumed I am not eligible.

I just want to say that I participated last year and I really enjoyed it. Solve ME has spread the appointments out so that we don’t have to participate in so many over a short time.

https://go.solvecfs.org/webmail/192652/234547566/68c230ff14890fe8c7eb25d3f23d1178ea7e6a5b7285a89b48d46703a219d202

From my journal article on gender disparity in the funding of diseases by NIH. Look carefully at the second sentence of the then NIH Director. “In 2015 testimony before the Senate Appropriations Committee, Francis Collins, Director of NIH, stated ‘Generally we look at the public health burden and it is a very-well-established way to do that. We also look at scientific opportunity because it’s not going to be successful to throw money at a problem if nobody has an idea about what to do about it. We look at what our peer review process is telling us about the excellence of the science.’ – C-Span. National Institutes of Health Fiscal Year 2016 Budget. Hearing of the US Senate Committee on Appropriations. 30 April 2015. Available from: https://www.c-span.org/video/?325686-1/hearing-nih-fiscal-year-2016-budget.” This explains why NIH has not wanted to put money into ME/CFS. They want to be able to tout their successful investments, and ME/CFS does not offer a quick return on investment. I might add that as a general rule, NIH is not in the business of funding diseases. Rather they want to fund excellent research, independent of whom it helps, and let the chips fall where they may. Hence not only does ME/CFS get ignored, but so do many diseases that affect predominately women.

Excellent insight!! And yes, all they ever had to do to get ME/CFS dismissed and trivialized was to say it predominantly affects women. That’s the kiss of death for us, from doctors to governmental decision makers. I have often wondered why we don’t just say that it predominantly affects men. Money would flow to us like milk and honey in the promised land.

I agree with you Art, I think the same, you just put it better than me!

Art Mirin

Thank you for writing your article addressing gender disparity.

There was an article comparing impact of me/cfs on patient’s functioning, vs how other diseases impacted people’s functioning, and relating how much money was spent per number of people on the compared diseases.

Somehow i feel there is something still missing that putting your research, and that of this other researcher, together, might be a rapid gain.

That’s an extremely insightful point. They want wins to look good and are less focused on plodding through basic research. They want to be able to show how successful they are. It’s a very political attitude.

Perhaps if someone in Congress threatened to take all the ME/CFS and long covid research elsewhere (an academic institution), it might wake the NIH up. Let them know their approach isn’t appreciated and they have a vote of no confidence. If the only research that gets done is that which gets quick results and makes people look good, then nothing would really ever get done. The NIH needs an attitude change.

Art your following statements reveal a very weak excuse not to research a disease which is so prevalent:

“From my journal article on gender disparity in the funding of diseases by NIH. Look carefully at the second sentence of the then NIH Director. “In 2015 testimony before the Senate Appropriations Committee, Francis Collins, Director of NIH, stated ‘Generally we look at the public health burden and it is a very-well-established way to do that. We also look at scientific opportunity because it’s not going to be successful to throw money at a problem if nobody has an idea about what to do about it.”

They have not measured the heavy public burden in the case of me cfs. It is a pathetic excuse to say that diseases where they do not have an idea what it is about should not be funded. Bodies raising awareness or giving funding to gender inequality issues should be made aware of this.

They haven’t at all measured the disease burden of ME/CFS! Nor have they given us the money to do so. Art and Lenny Jason have on their own.

Judi and Sunie,

Are you aware that Art Mirin, Mary Dimmock and Leonard Jason wrote a paper in 2020 called ‘Research update: The relation between ME/CFS disease burden and research funding in the USA’? Cort did a blog on it:

https://www.healthrising.org/blog/2021/04/03/chronic-fatigue-syndrome-most-neglected-disease-nih-national-institutes-health/

Also Art Mirin wrote a blog himself entitled ‘The Education of an Unlikely ME Advocate’

https://www.healthrising.org/blog/2021/06/16/education-unlikely-me-chronic-fatigue-advocate-mirin/

thanks for reminder

🙂

Do you remember the rationale they gave fairly recently not to fund a diagnostic test because there is no treatment if people do get diagnosed with me cfs?

Is this fair government?

Cort, you have hit upon a splendid, SPLENDID name for ME for the purposes of our needed publicity – “The Original Long Haulers.” People reading this blog – please use this often in what you write and speak about when talking about ME. How much easier for the public and Congress and the media to get what we are saying about the disease by calling ME “the original long haulers.” And it makes the point even stronger that the NIH is actually negligent in its omission of such people (ME patients) in the massive long hauler studies now underway at the NIH. There is simply no excuse they can manufacture which rings true on that omission! It’s still pure bias.

Use it, use it, use it!!

Great column, Cort ! Billie Moore

I hope that the requirement from the government of a comprehensive and extensive public media campaign covering mild to very severe ME; including on TV, is part of Solve ME/CFS and other organizations’ plans in our talks with Congress. Otherwise, what good is research to those of us who will be dead from lack of care, malpractice, and/or poverty before any research results are in? We are not expendable!

I also hope that the same kind of funding Long COVID is receiving will be required that ME receives as that figure is about what we should have been receiving all along.

Lastly, whenever I write to my members of Congress, or add my comments to an organization’s form letter that gets sent to my members of Congress, I request a Congressional investigation into the mishandling of this disease and I wish that our organizations would lobby for this too. We deserve accountability and justice!

Fauve!? I learned from this piece that Fauci originally helped relegate ME to the dustbin! . But in a recent NYT piece he was quoted endorsing the LongCovid-ME connection and overlap: have you/anyone else in the ME community, asked him to go further and speak directly to the press and congress about this apparent moment of CLARITY? Whether we’d press him for a mea culpable let him slide on that — a statement from

him would be huge. How might we go about making a formal ask to him? .

Also—who ARE the big powers mentioned here snd by ME Action that are hurting us with NIH and elsewhere. Let’s take it directly to the specific board members snd money folks behind Big Disease and any other big powers—and shame them. Can you report on who they are? Meanwhile, Cort, Thank you. You are my/our hero. There’s nothing like good journalism to help us survive and fight the pain, anger and gaslighting.

Whoops! Typo!! I meant FAUCI!!!

Cort, about 2 decades ago, maybe 3, Congress actually did include a LINE ITEM in the budget of $5 million for NIH to dedicate to CFS research.

But Congress is apparently not in charge, at least not when it comes to CFS. Congressional direction is considered “a suggestion” not a “command”, apparently.

What did the NIH do with the one time $5M dedicated to this long neglected cause – in an environment where the highly debilitating disease of “male pattern baldness” was being studied with a budget in the double digits, year after year?

The NIH took that money from Congress, and spent it all on other stuff. Not one penny went to CFS. I don’t think Congress followed up.

So. Now you know.

There are also the letters and in person questioning from Congress over the years to the NIH often including timelines for action. These timelines for action include responding back to Congress about what actions have been taken by the NIH, and it seems the NIH continually doesn’t respond back to Congress, or the NIH does a bogus song and dance about how they take ME/CFS seriously, and Congress doesn’t follow up any further.

President Obama even promised to look into ME/CFS but later followed up by blaming Republicans instead of the administration he appointed! Wow, that’s really some major gaslighting. We are not political fodder!

Andy Slavitt who worked in the administrations of Obama (Medicare & Medicaid) and Biden (temporary Senior Advisor to the COVID-19 Response Coordinator) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Andy_Slavitt recently tweeted this out:

We slowly but surely developed the tools to live a mostly normal life for most people in the most likely conditions.

While this is a lot of qualifiers, it must be a reminder that it’s how the world works.

Worse for the poor, the old & the sick. And always uncertain. 23/

9:07 PM · Feb 11, 2022·Twitter for iPhone

https://twitter.com/ASlavitt/status/1492319423075475456

No Mr. Slavitt, it’s not how the world works, it’s how the government doesn’t work and how it fails its people! While he was tweeting about COVID, this is the government attitude seemingly about most things.

Furthermore, I live in Massachusetts and with so many members of Congress supposedly on our side, you would think that if they can’t make changes on the federal level that they would help us on the state level.

For example, by increasing our state benefits to get us out of poverty so we can eat, afford our expenses and have safe housing of our choosing. How about creating a patient friendly, reality based disability process and many, many, many other things I’m too sick to write about.

We are adults having to live like we are children in a massively f***ed up abusive family who starves us, can’t guarantee our safe shelter or needs, doesn’t give us medical care, but gives us a few coins of allowance as though somehow we are subhuman and different than they are and that that is all that we deserve!

I hope as many people as possible get involved in whatever way they can to make the politicians do their jobs.

Thanks for your clarity in calling it as it is.

Yes, this is not how the world works; it is how corrupt generations of legacy bureaucrats control and stay wealthy, from the highest to the lowest levels, from our longterm suffering.

Expecting the strangle holders to release their hold on power is not realistic.

In contrast, look at how Canadian citizens, and citizens internationally, are demonstrating by the millions for antiauthoritarian decentralized leadership that truly serves the vulnerable poor as well as the well off. Those who stand to lose power have no problem denying people civil liberties; Trudeau is one current example. He and his globalist buddies will lose during this massive awakening. This has great implications for the future of decentralized power in which the disenfranchised disabled have easier access to resources.

“People have the power; but the people have got to use it” sings Patti Smith:

— And we witness in clearest daylight now that the people who have been pushed off the Bell curve need their voices heard the most, and most often have the least physical strength to demonstrate their power. So partnerships and alliances with successful disability support groups need to emerge, and fast, from these new decentralization of power movements that are the future of healthier societies worldwide.

Thanks, Cort, for another excellent article.

Well, I am a med researcher with more than 15 years of experience who has researched for years on ME/CFS (as I’ve got the syndrome, even though now it’s at 15% or less). I have leads and I begin to increasingly take seriously my musings/feeling that it was intentional – that CFS was created, and maybe there was a change done in the human DNA through a CRISPR carrier virus – and it seems to me that to reach the cure we might discover a part of the DNA that might have been changed and revert it back to a healthy option through CRIPR (Cas9, etc) technology. All I’ve studied about ME all gets very, very suspicious when one connects mant dots. Would also definitely explain the NIH’s absolute lack of interest in finding the truth out – as we well know Fauci has been implicated in antiethical (straight out evil, let’s say) virus research.

To dig into the primary reason Fauci squelched ME/CFS studies, read Dr. July Mikovits’ book PLAGUE OF CORRUPTION. According to this virologist (who worked at the National Cancer Institute), Fauci did everything he could to discredit her and her discovery (with Dr. Frank Ruscetti) that retroviruses were often found in vaccines grown on animal cell lines. (Note: Don’t be surprised to see these two scientists smeared when Googled. I would suggest reading the book before you decide whom to believe.)

Tuskegee.

Is it still too soon to make comparisons and ask questions without being pooh-poohed and tsk-tsk’d and patted on the head as a delusional ‘conspiracy theorist’? Just for entertaining the possibility?

Or do we need to wait another decade or so before we’re comfortable even hinting at it?

Asking for a friend. A whole lot of them. Not to mention all those who’ve died while we’re all waiting.

Tuskegee only lasted 40 years before the truth came out, after all. How many decades have we all been dancing around this?

Because our illnesses touch the lives of so many, I’ve often thought that delving into the personal lives of our congress people to see which of them is affected in any way would be a good idea. Those would be the people who would be more eager to get something done on our behalf. Any proposals or pleas for help should be addressed specifically to them.