In part II of a series of blogs on breathing and oxygen utilization, a long COVID exercise study suggests that dysfunctional breathing patterns may help explain the exercise intolerance found.

Dysfunctional breathing – Could it play a core role in long COVID and ME/CFS? (from Sumiaya – Wikimedia Commons).

A recent blog focused on a large CDC exercise study revealed that problems with gas exchange” – the movement of oxygen into the body and the removal of CO2 from it – were common in ME/CFS. Because oxygen – a gas – fuels most of the energy production in our bodies, and energy production produces CO2 which becomes toxic at too high of levels, stating that gas exchange problems exist in ME/CFS is tantamount to saying that energy production problems exist. Anytime we see “gas exchange”, then we can think “energy production”.

The CDC study found that a strange breathing pattern was present: people with ME/CFS were breathing more slowly and deeply than usual during exercise. This type of breathing pattern has been associated with exercise intolerance before, and the authors suggested it may have resulted from a compensatory attempt to try to force more oxygen into the body.

ME/CFS isn’t the only disease, though, in which bizarre breathing patterns have popped up recently during exercise. A long-COVID exercise study, “Use of Cardiopulmonary Stress Testing for Patients With Unexplained Dyspnea Post–Coronavirus Disease“, did the same. While it was called a “Rapid Report”, the study dug deeper than usual into the individual patent findings – illuminating in more detail than we’ve seen before a variety of breathing patterns found.

This paper is also notable because it’s the first non-David Systrom study that I know of to use invasive exercise tests (albeit in a small sample) in ME/CFS or long COVID. Let’s hope there’s more of that on the way from Dr. Mancini and Dr. Natelson.

The Study

The study involved 41 PASC (post-acute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2) or long-COVID patients. The average age – 41 – indicated these people had gotten hit in the prime of their productive years. The authors – one a longtime ME/CFS researcher – quickly connected post-acute sequelae SARS-CoV-2 infection (PASC) patients, otherwise known as long haulers, to ME/CFS by stating that PASC’s major symptoms are consistent with a diagnosis of ME/CFS. They also noted that no less than 27% of survivors of the first coronavirus epidemic (in 2005) met the criteria for ME/CFS four years later. They made sure that nobody was going to miss the long-COVID/ME/CFS connection.

The patient group was somewhat specialized – more than 3 months after “recovering” from the initial viral attack all of them still experienced shortness of breath. All underwent a maximal cardiopulmonary exercise test (CPET) which involved the participants bicycling to exhaustion. The CPET was a bit different from others, though, in its close tracking of the breathing patterns.

Results

The Gist

- Not long after a blog on a major CDC exercise study that exposed problems with “gas exchange” and breathing in ME/CFS, comes a study which did the same in long COVID.

- Note that because oxygen is the gas that fuels most of the energy production in our bodies that problems with gas exchange in the context of ME/CFS and long COVID could very well mean problems with energy production.

- This study employed a regular cardiopulmonary test that measures cardiac (heart rate, stroke volume) and pulmonary factors (breathing rate, CO2 levels, etc.) participants bicycle to exhaustion. Some of the participants also did an invasive exercise test which measures the same factors but in both oxygenated blood in the arteries before the blood hits the muscles and the “used up” or deoxygenated blood in the veins after it leaves the muscles.

- Forty-one long COVID patients experiencing shortness of breath participated in the study.

- Sixty-percent of them displayed what they called a “circulatory impairment”. These patients never generated much energy (low VO2), burned through the aerobic energy available to them quickly, and hit their anaerobic threshold early. The authors appeared to believe that the oxygen in the blood is not getting to the muscles in sufficient quantities in this group.

- A wide variety of factors could be causing this is including reduced blood flows to the lungs or muscles because of blood clots or blood vessel problems. In that vein, a recent study suggests that reduced blood flows to the small blood vessels in the lungs may be a big deal in long COVID. If that’s so it would fit other microcirculatory findings in ME/CFS and FM. (A blog is coming up).

- The study also found evidence of “preload failure” where insufficient amounts of blood were being returned to the heart – thus reducing stroke volume – the amount of blood each heartbeat pumps out. Because the veins are mainly responsible for increasing the stroke volume during exercise – some to do with them – is likely responsible for that.

- About 10% of patients had ventilatory impairments that either prevented them from filling their lungs up properly or filling the blood reaching the lungs with oxygen.

- The main focus of the paper, however, was on the remarkable extent of dysfunctional breathing patterns found. 88% of the participants exhibited one form or another of dysfunctional breathing.

- During exercise as the breathing rate smoothly climbs the amount of air moved should increase significantly early and then moderate and finally reach a plateau sometime before a person reaches exhaustion.

- This almost never happened in long COVID and a number of different breathing patterns were seen. All of them displayed a kind of jerky, up and down pattern which indicated a system under extreme stress which tried but failed to find its ground. Some even exhibited a reversal of the normal breathing and heart rate patterns found during exercise (See graphs in the blog.)

- The fact that only about half the long COVID patients met the criteria for ME/CFS while 88% displayed strange breathing patterns during exercise and 60% hit their anaerobic threshold early suggests that the criteria may be missing a significant number of people with ME/CFS-like illnesses.

- Similarly, while about half the participants exhibited a normal VO2 peak – a measure of fitness – almost all them also suffered from dysfunctional breathing patterns – which can affect exercise intolerance.

Circulatory Impairments – With almost 60% of the patients falling into this category, this was the biggest single group. Long-COVID patients with reduced VO2 (oxygen consumption; i.e. energy production), early onset of anaerobic threshold, reduced VO2 pulse, and elevated VE/VCO2 slope were classified as having a circulatory impairment.

These patients never generated much energy (low VO2) and burned through the aerobic energy available to them quickly and hit their anaerobic threshold early. The authors appeared to believe that the oxygen in the blood is not getting to the muscles in sufficient quantities in this group.

They noted that a wide variety of factors could be causing this: damage to the heart, reduced perfusion of the blood to the lungs or muscles via blood clots or blood vessel problems. A recent study using a new technique suggests that reduced perfusion to the lungs because of damage to the microcirculation may be a big deal in long COVID. (A blog is coming up.)

Dysfunctional breathing patterns were common (60%) in this group, but with 40% of this group not demonstrating dysfunctional breathing, it was clear that it was not necessary to produce circulatory impairments.

Dysfunctional breathing, on the other hand, was very common in patients with normal VO2 peak levels – a group that would be classified as having a normal exercise capacity. They tended to have other problems, with most of them exhibiting odd breathing patterns. The upshot is that only 2 long haulers in the study had completely normal results.

Preload failure – Systrom has found preload failure – the inability of the veins to return sufficient amounts of blood to their heart. This study found that preload failure is present in PASC or long COVID as well.

It turns out that the increase in stroke volume found in the heart during exercise is mostly accomplished by increasing “venous return”. Increasing venous return is accomplished by constricting or narrowing the veins by the muscle pump which alternately opens and constricts the veins, and by the respiratory pumps which involves the expansion and the reduction of the chest wall.

Ventilatory Impairments – Patients with low breathing reserve, O2 desaturation, or with RR >55 beats/min with exercise were identified as having a ventilatory impairment. Breathing reserve is the extra space in your lungs that you tap into when you exercise and need to move more air. These patients had problems with their lungs. Either their lungs’ ability to move air was maxed out, or they were having trouble getting oxygen into the blood from the lungs. About 10% of the participants fit this category.

A Ventilation-Impaired and Dysfunctional Breathing Disease?

Breathing easily and fully is one of the basic pleasures of being alive… It provides the oxygen for the metabolic processes; literally it supports the fires of life. Alexander Lowen

A major focus of the paper was on dysfunctional breathing patterns and/or problems with ventilation. A “primary ventilatory limitation to exercise” was not expected to be found, and was not seen. This appears to refer to the fact that the lungs of PASC patients were largely capable of moving air adequately – they just did so in a strange way.

While “a primary ventilatory limitation” was not found, almost all the patients (88%) exhibited, in one form or another, odd problems with ventilation or breathing. They demonstrated weird breathing patterns (dysfunctional breathing), resting hypocapnia (low CO2 levels), and/or had an excessive ventilatory response to exercise (elevated VE/VCO2 slope); i.e. they were moving more air than was necessary.

Dysfunctional breathing patterns were the most common problem (63%) found. During exercise, the amount of breath moved (ventilation) should track closely with CO2 levels – as the primary goal of breathing during exercise appears to be to remove the CO2 that gets built up as a result of energy production.

Generally, the pace of breath should slowly increase during exercise. The tidal volume – the amount of breath moved – should increase early but over time should moderate. As we get close to exhaustion during exercise, the amount of breath being moved in and out of the lungs doesn’t really change that much; it actually levels off well before we reach that point.

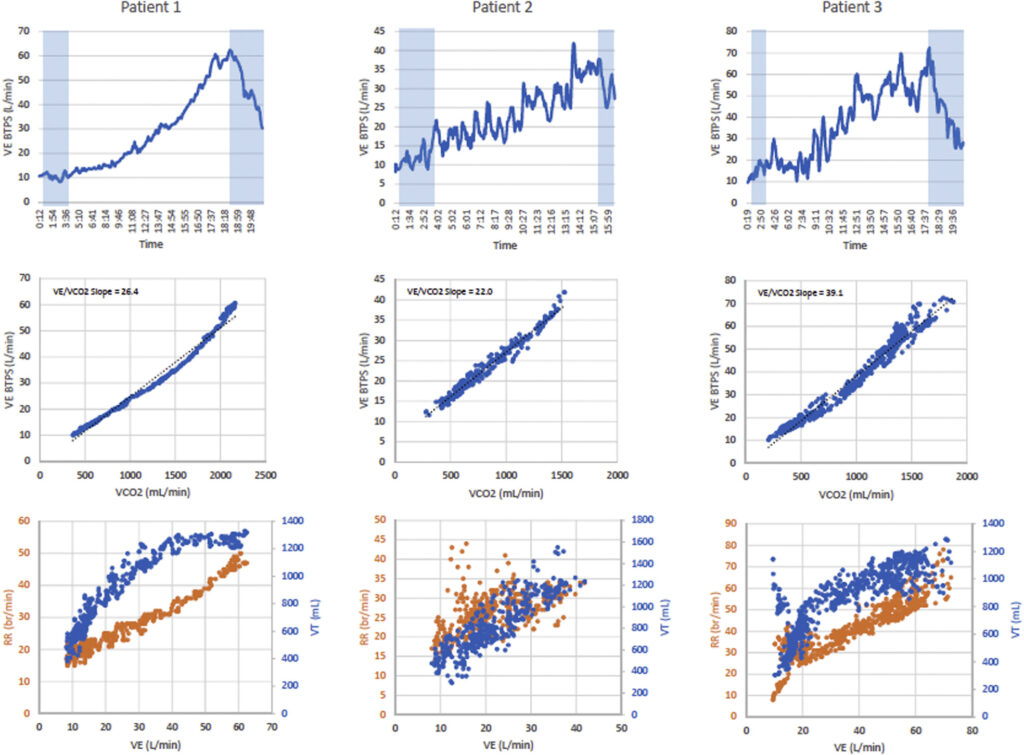

In this shot of a normal breathing pattern on the left-hand side of the graph, you can see that ventilation (using the BTPS measure) – the amount of breath moved – increases smoothly over time. In the bottom figure, see how the breathing rate (brown line) slowly and regularly increases over time, while the amount of breath moved (using minute volume – the amount of air moved over a minute of time – blue) shoots up early and then moderates and finally levels off towards the end of the exercise. Apparently, the heart rate and amount of air moved should join as the patient reaches exhaustion. It’s the picture of a clean and efficient breathing pattern.

Compare the smooth patterns seen on the graphs on the far left (the normal patient) with the jerky and jumbled patterns seen on the right. The blue lines refer to ventilation while the brown ones refer to breathing rates.

Compare that to some of the PASC participants with decidedly abnormal breathing patterns seen in graphs in the center and the right. The increase in the amount of breath moved is jagged – the peaks of ventilation are followed by abrupt drops – and the breath rate is all over the place; sometimes the person is breathing much faster than normal, sometimes slower. No early increase in the amount of breath moved gives way to a moderate, and finally, virtually no slope at all.

Instead, there’s a jumbled mass of ventilatory readings as the amount of breath moved moves up and down. It’s a picture of an agitated system that just cannot settle down and find its ground.

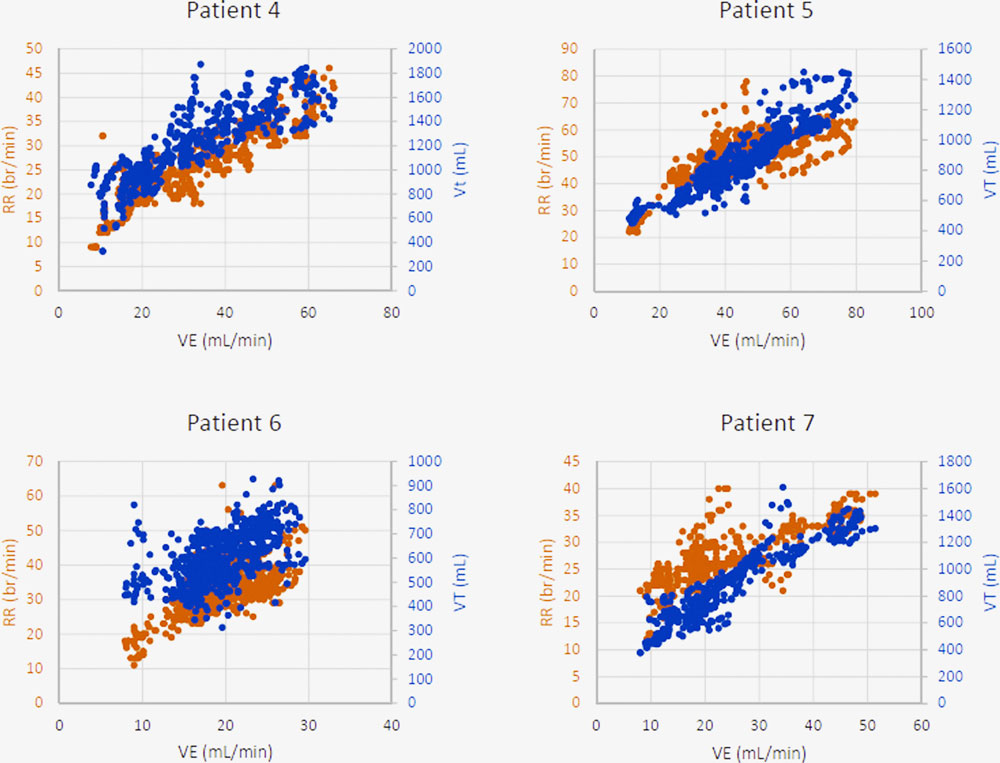

Different variations occur. In these graphs below, the breathing rate and the amount of air moved through the lungs merge. We should be seeing the amount of air being moved ramp up quickly, but it’s unable to do that despite the fact that the breathing rate is increasing. Some sort of limitation is clearly occurring. Instead of the graphs of the heart rate and amount of breath moved joining as the patient reaches exhaustion, they join almost immediately in the long-COVID patients with breathing dysfunctions.

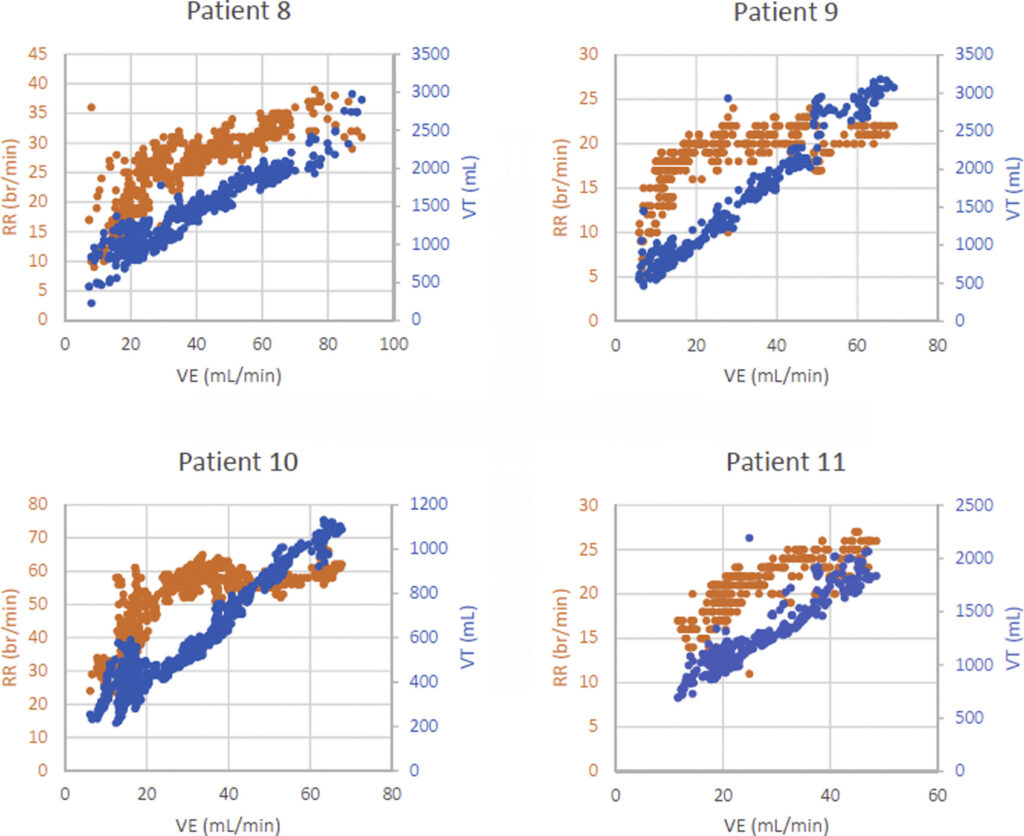

In some patients, the graph actually flips itself – and a reverse pattern of breathing is seen: in the patients below, the exercise prompts very rapid breathing – and a lot of air being pumped – perhaps in an effort get more oxygen to the tissues. The graphs of the heart rates and the amount of air being moved are joined from the get-go. Nor does the amount of air moved plateau at some point – it just keeps its jagged rise.

Notice in patients 9 and 10 that the graph switches again as the patient nears exhaustion – the heart rate levels off while the amount of air being pumped dramatically increases. These appear to be very strange patterns. Compare these graphs to those on the left-hand side of the first image to see the reverse pattern present.

The authors noted that these jerky and strange breathing patterns interrupt the rather complex breathing process, possibly leaving extra dead (unutilized) space in the lungs behind and/or causing intrapulmonary blood shunting, which occurs when the blood doesn’t get fully oxygenated in the lungs. Either way, the efficient flow of oxygen into the body and CO2 out of it gets impacted.

The authors noted that dysfunctional breathing patterns can cause symptoms such as shortness of breath, fatigue, chest pain, and palpitations, and that breathing retraining may help. Systrom, Cook, and others have suggested that the breathing problems may be secondary to the energy production problems that studies have suggested are present. It’s possible that breathing retraining could help, though, and a clinical trial is underway in ME/CFS. (A blog on that is coming up.)

“Hidden” Problems? (Or what the heck is ME/CFS anyway?)

This study also showed how seemingly normal results in one area can hide abnormalities in another. For instance, peak VO2 (think peak energy production) has received a lot of focus in ME/CFS and is often used as an assessment of fitness. A normal peak VO2 found was found in almost half the participants in this study. Without the extra assessments done in this paper, it would have obscured the fact that almost all the patients with normal peak V02 levels exhibited unusual breathing problems – and unusual breathing patterns can, by themselves, affect exercise tolerance.

Similarly, the fact that “only” about half of the PASC patients (46%) met the criteria for ME/CFS may tell us more about the ME/CFS definition than about the patients themselves, as the vast majority of PASC patients demonstrated problems during exercise. Ditto with the fact that about 60% of patients hit their anaerobic threshold earlier than expected, yet only 46% met the criteria for ME/CFS.

Michael Gallagher’s and Brian Schulzes’ experience with ME/CFS indicates that it can take many forms and produce significant disability before one meets the criteria. At some point a redefinition – based on biological biomarkers that track exertion-based problems – is surely in order.

One thing this study did not find was much exercise-induced hyperventilation. This finding tracks with Cook’s recent big CDC exercise study which also found little hyperventilation but did find an altered breathing pattern consisting of slow, deep breathing in ME/CFS.

Conclusion

Breathing has come to the fore recently in both long COVID and ME/CFS. (Diaphragmatic breathing (from Wikimedia Commons by John Pierce).

This exercise study dug deeper than any before it into breathing issues. It struck gold when it found that 88% of long COVID participants displayed a “breathing dysfunction” during exercise. The variety of different breathing dysfunctions found demonstrated, once again, that many roads can lead to Rome; i.e. to exercise intolerance. Demonstrating how revealing exercise tests can be, only 2 of the long COVID participants had a normal exercise test result.

Evidence of some sort of circulatory impairment that is preventing the fully oxygenated blood from getting to the muscles was common and preload problems were found as well. While the cause of circulatory impairment was unclear – and may be caused by metabolic problems – the authors suggested that breathing retraining exercises might help and a blog will be up on them soon.

With a large CDC study finding that problems with “ventilation” and breathing are common in ME/CFS and the recent publication of other long COVID breathing studies – one of which that’s bringing problems with the microcirculation to the fore – we will likely see more and more emphasis on the possibly vital issue of “gas exchange” (read energy exchange) in these diseases. Could the problem simply be not enough oxygen (i.e. energy) getting to the cells? A blog on that is coming up shortly.

My daughter has been disabled with ME/CFS or post Lyme for about 13 years. She has periods where I notice her holding her breath because of the constant pain. My observation is that the pain causes her to stiffen up and so affect her breathing.

I’m not surprised at all and I’m sure I do the same and Cook Dane, who has investigated pain in fibromyalgia has suggested this is happening.

The advice Buddhists give is to allow the pain to be – to even try to embrace it – and breathe into it. Ashok Gupta gives similar advice in his Amygdala Retraining program. I’ve recently been doing stretching exercises which I’ve found have been able to relieve the pain somewhat and breathe more deeply and easily. It’s nice.

Have you done the retraining program? Did it help? What does it actually do?

The Amygdala Retraining program? I tried it a long time ago and it was not successful for me. Some people do really well with it though. I’ve been trying the Buddhist technique of kind of embracing and breathing into negative body sensations and it can be helpful at times.

I’ve long noticed I can have trouble taking a deep breath when I exercise. Water walking in a warm water pool has been my favorite form of exercise for fibromyalgia. When I get too tired, I notice myself slowing down and yawning. It seems to be involuntary at those moments. I have also been out for a walk and had to suddenly stop, turn around, and go to the car so I can sit down and breathe. Last week, I was out doing photography on a pontoon boat looking for osprey nests. I became fatigued and had to sit down, and put my camera down so I could breathe. I wrote a short piece about it, breathing in the moment. Experience has taught me it is absolutely necessary at times.

Ted Donnelly

Sorry to hear your daughter is experiencing so much pain.

( i don’t know why, but i find i often breath-hold whether in pain or not)

My daughter holds her breath too, no pain involved. It’s something I noticed very early on, years before her ME diagnosis.

The inhalation activates the sympathetic or fight/flight part of the nervous system. The exhalation activates the parasympathetic or rest and digest part of the nervous system. Based on my personal experience I’m not all surprised to find more breath holding than breath exhalation.

We need rubbing out and to be drawn again.

Crispr anyone?

Totally. that would be amazing. yes just splice out those defective genes and let’s start again..

The sequel is better in this two-part series! Thank you as always Cort.

Much looking forward to diving into this one more.

Speaking of which, this all reminds me of my short-lived scuba diving career. On my first and only pair of ocean dives, I nearly used the whole tank even though these were easy/casual dives. I came quite close to having to bust out the techniques from training to borrow air from my dive maser. This was before what I consider to be my ME onset, but it makes me wonder if something was going on earlier.

Talk about diving into a subject (:). What an interesting observation…..

Thanks Cort. Re the question about whether these lc patients do/don’t have ME/CFS, any chance you could update the blog to add what diagnosis criteria they were using? Also, did they discuss which specific criteria the lc patients weren’t meeting?

Good question. Interestingly, they used the old Fukuda criteria which is not nearly as strict as the Canadian Consensus Criteria! They did not say which parts of the criteria were generally missed.

wonder if there is any way to ‘see’ if the medulla is sending out the proper signals, or if its signals in response to carbon dioxide are out of whack.

if the medulla’s signals are not jiving with what they should be–based on percent of carbon dioxide–then it might be out of whack while sleeping also

They did, I believe, mention that the signals regarding CO2 concentrations could have been disrupted or misinterpreted but did not assess where that was happening. I don’t if its possible to assess that or not.

I have had ME for 30-plus years. Since the pandemic began I have done this breathing exercise at least 5 times a day: breathe in for 5 seconds, lifting first the stomach area and then the chest; hold for 5 seconds; and then purse the lips as if whistling and breathe out slowly. I no longer have the semi-numb face and I no longer suffer from a painfully cold nose in the colder months of the year. And I generally breathe better.

I am Dutch, first: many thanx for your blog!

I have ME/CVS since I was 12, now I am 58. I also have fibro. Only recently I am retraining my breath. Specificly by nose breathing day and night, and by excercising several times per day for 15 minutes. Then I breathe lightly, slowly and from the belly. In this way I inhale much less oxygen than before, which occurred because I inhaled far too much air (but very slowly). I appeared to be very relaxed to people who were watching, but was in fact extremely stressed. Just as you are when the dorsal vagus nerve is overstimulated.

My exercises do help a lot. Especially I sleep much much better, and I feel much more relaxed.

Greets to you all!

You may have been depleting your carbon dioxide levels too much with your former breathing pattern as well. Glad to hear it’s helping. 🙂

My son and I both have cfs and one of our biggest problems is breathing. When we’re feeling our worst, our chests feel tight and heavy and we can’t catch enough air. Also, for years, when I’m at my very worst, I yawn a lot. Not normal yawns like when you’re sleepy, but gaping yawns to suck in enough air to breathe.

I’ve noticed that. I wonder if what you are doing is “sighing”. Sighing is actually an automatic procedure that we all do periodically mostly without realizing it to pop the air sacs in our lungs back open – which apparently close regularly. A lot of sighing, though, can indicate a respiratory condition is present.

Another chronic breath holder here, combined with shallow apical breathing and not due to pain. I have worked quite hard on improving my breathing patterns with various breathing exercises and have worn a wide elastic belt to encourage tummy breathing. I have often felt that some sort of biofeedback might be useful but have not been able to find anything other than some expensive German equipment

There is a good (thin) book on breathing retraining by Patrick McKeown Close Your Mouth and Breathe. Very helpful exercises.

“Instead, there’s a jumbled mass of ventilatory readings as the amount of breath moved moves up and down. It’s a picture of an agitated system that just cannot settle down and find its ground.”

Funny – this is exactly what my heart rate, blood pressure and pulse pressure were doing for the first 8 minutes of the NASA standing test, dancing all over the place. Until my pulse pressure became quite narrow, and then my HR galloped up. At that point I stopped, because I was going to pass out. (very narrow pulse pressure – my heart was ready to stop beating?)

Why it’s important to do the test for more than just 1-3 minutes (which is what the incompetent POTS ‘specialist’ here does)

Recently I read about Cushing’s triad. Sounds similar. It’s in response to the brain not getting juice. So goes in line with hypoglycemia. Which are exactly the symptoms I experienced during the standing test.

Sometimes my stress hormones kick in and rescue the falling BG, sometimes they don’t. When they do, the heart stats are different – they shoot up high.

I would add blood glucose measurements in real time with the breathing ones in these tests.

I wonder if heart activity measurements would correlate with the breathing ones. And with the blood glucose ones. Has anyone ever measured all of this and plotted out the relationships, instead of piece-mealing them?

I think this dance might also correlate with the body changing energy sources – from glucose, to fats, to enlisting stress hormomes to release glycogen stores to when it can’t, catabolizing tissues/proteins. So those that can still use their fats – diff beathing and orthostatic pattern, those with glycogen stores diff. Those with low adrenaline/cortisol, diff. Those with high nor-epinephrene, diff. Maybe maybe.

These energy substrate utilization patterns have been observed in the metabolomics studies.

Has anyone been tracking the brain during the ‘invasive’ tests?

Has anyone ever tied it all together in a study? If not, why not? How come all these parameters cannot be observed at the same time?

Does it matter? Will it simply just show why the different patterns?

The cause in the beginning still the same?

‘Do no harm’? Invasive tests that make you crash that perpetuate illness? Perhaps for some, that crash will be so hard that they will move in the scale of severity.

Sigh….

I was very intrigued by your elucidating questions M.

I’ve had this illness for 32 years. My daughter has had it for 28 years.

It has stolen our lives.

Why do these observations no move at a more rapid pace?

There are a million lives waiting on hold and so much unconcern. I add my heart broken ….sigh….

It’s Unconscionable.

This sounds like Dr. Paul Cheney’s theory of left diastolic dysfunction in the hearts of ME/CFS patients.

“The study also found evidence of “preload failure” where insufficient amounts of blood were being returned to the heart – thus reducing stroke volume – the amount of blood each heartbeat pumps out. Because the veins are mainly responsible for increasing the stroke volume during exercise – some to do with them – is likely responsible for that.”

Is it possible that Covid is actually triggering the same virus that causes ME/CFS and that long Covid is actually the same thing with a different name?

Yes, I’ve thought that reduced preload sounds a lot like Cheney’s diastolic failure idea. I would have liked to have known what he thought of the preload finding.

Betty I Mekdeci,

if you can take time to follow some of Bhupesh Prusty’s work with epstein barr virus and mitochondria. He has a twitter account.

Prusty found that a few affected cells would signal to MANY other cells, and the resulting ‘sickness’ of mitichondria would become widespread.

He was looking at this in relation to cfs and covid.

(interestingly, the mitochondria also have some sort of immune function too)

Finally. Respiratory disorders. 1 of the most important and serious problems in ME/CFS. At least for a large group. Doctors dismiss this as hyperventilation. In reality, there is an underlying cause. If you know these then you know what ME/CFS is. So many intelligent people and doctors. No one can solve this riddle. I’ve been trying this for almost a quarter of a century. Microcirculation, medulla, mitochondria, diastolic dysfunction and much more… or compensation?

I’m interested that they’re hypothesising that breathing retraining could be a solution. Am I the only one feeling sceptical? Something’s driving the altered breathing patterns; retraining implies it’s habitualised behaviours, which I’m not convinced about. Even if the retraining modifies behaviour, isn’t the person’s (uncorrected) physiology is going to be fighting that?

You could try it yourself and see what it changes for you.

Easy place to start is by breathing through your nose, instead of mouth, even during sleep. Watch how much you talk, etc

The source of knowing is experimentation and doing.

Godspeed!

Thanks, M. I have worked with this a fair bit over the decades and do breathe through my nose. My own breathing patterns are variable and definitely affected by illness. But it still stands: if the physiology driving it is out of whack, changing the breathing is still only addressing the symptom; it might be better than nothing in the absence of something, but it’s not sounding like a cure… (and believe me, I want it to be cure!).

Everything influences everything.

and there are these loops that reinforce each bad thing going on.

Anything that can help you get out of the stress response, can be helpful.

Not for nothing Sarno works for some.

[not me. ha!]

I like what Feldenkrais said on breathing ‘right’: I can’t find the exact quote, but it flows out of this other one: “Movement is life. Life is a process. Improve the quality of the process and you improve the quality of life itself.” If someone is telling you there is one way to do something, and one way only, they are teaching you how to be an idiot. Something like this. There are quite a few sessions exploring how one engages the act of breathing.

Me too! I want my cells to snap out of that stressed/sick quorum and re-orient themselves into a healthy state again 😉

I agree. I’m quite well versed in functional breathing since before I got covid (speech language pathologist and yoga teacher). Sometimes it works to guide the breathing into a more functional/normal/less stressful pattern. But whenever the body gets under pressure (which happens all the time) it’s extremely hard to establish that normal pattern even though I am super familiar with it and know how to gradually change the ratio of exhale and inhale so that, supposedly, the breathing pattern would change as a natural response to the blood gas situation altered by change ratio of inhale:exhale duration. It doesn’t happen.

My guess is that breathing exercises can help but that the metabolic problems are central.

Sometimes the most basic things, like breathing, can be overlooked!

Being a person with EDS, in the last few years I have noticed that my nasal valves have collapsed and so I probably do about 80% of my breathing through my mouth. I also know my breathing pattern is shallow, shallow, shallow and then I need a big breath to compensate–and repeat. My fatigue wasn’t as bad when I was younger and doing yoga (breathing exercises), but I’m not sure that aging and having more co-morbidities are not the cause. My HR is still continuously high as it has been throughout my life. Ah, those floppy (EDS) tricuspid valves and concurrent regurgitation. And now I fall asleep quite often in the afternoon. What can be done–oh–what can be done?

Hi Cort, I have started a breath program that teaches about this issue. Ari Whitten (from the Energy Blueprint) and Patrick Mckeown (wrote the oxygen advantage book) designed the program. As well as breath holding and yawning being a symptom of dysregulated breath (which they think is at epidemic levels), they are suggesting unconscious overbreathing is a major problem that causes us to exhale too much CO2. The high levels of CO2 in the blood cause the blood cells to hold on to the oxygen so it cannot get into the cells/tissues, but is still circulating on the blood, so a pulse ox reading would look normal, but in reality that oxygen is not utilized effectively.

To reverse this issue they are training people to breathe more gently to the point of air hunger for a few mins at a time (I think based on Buteyko breath) along with other breathing, breath holding and relaxation techniques. The gentle breath/underbreathing is key to the program, and signals the cells to take up more oxygen as it shifts the sensitivity of the receptors (like living at altitude the body adapts to less O2). There are other reasons as to why this breathwork can be beneficial, one being that nose breathing increases nitric oxide production. This is my simplified understanding but I think it is exciting.

I also recently learned form a colleague some yoga mudra finger techniques that help to regulate breath patterns where you can actually feel the shifts in your body. This was a revelation to me, I have practiced yoga for many years and never experienced this before. She learned it from her Physiotherapist who has research to support this, and I plan to look in to this more as it was so astounding.

Just wanted to share this in case it’s interesting or new to you. I love your blog, it has really helped me in my own recovery/remission from fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue, POTS and sleep apnea. Thanks for all that you do.

Thank you for your information Kim (and the blog, Cort). Do you feel the Ari Whitten program has helped?

In the last breathing blog, one person brought up the use of nebulized budesonide for long Covid and CFS, and it will be interesting to see if it being found to help with breathing and therefore some of our symptoms.

I see in the program facebook group it has helped many people. Personally I am not practicing the breath enough to see a difference, but I think the program is excellent and I really love all the science they share, how they have divided it into 4 programs targeting different issues, and I enjoyed the many different guided breath practices with music. Another reason I may not have noticed a difference or be more motivated to practice is because I have my CFS/fibro symptoms in remission and I mostly wanted the program to learn their techniques so I can share them with friends and clients as I became a health coach a few years ago.

I think nebulizing can be very helpful, some people have used essential oils, glutathione, iodine, H2O2 and NAC and found them to be helpful with respiratory issues. There is even research to support nebulizing only salt can reduce asthma symptoms, so it’s worth trying out to see if it helps.

Thank you for the information! I am a long hauler with breathing problems. In the beginning my breathing was super fast, like I was doing exercise, and over time I was able to slow down my breathing, but I breathe very deep. At night I breathe super fast and shallow. I thought maybe slow, deep breaths were good, but from these articles and comments I see that it is a sign of problems. A year ago I read an article saying long haulers typically have too low CO2 levels because of hyperventilation. Because of that I started breathing as slow as I could, on the border of being uncomfortably low on air (since I figured it was a false signal about high CO2). I have not been very successful though. My breathing is messed up. I belly breathe and nose breathe, so that is not the problem. I read you post and wonder, do you think that a longer stay at altitude could be beneficial? We have a cabin at high altitude, and I notice my symptoms are worse there, but then when I come home they are better than before I left, and I don’t understand why. I could potentially stay there for weeks or months if I thought it would help.

I think breathwork can be very nuanced, or example, benefiting from different breathing patterns throughout the day, a more stimulating breath practice in the morning and a more relaxing breath in the evening. Figuring out what works for you as an individual is key. Often with long hauler, people can have elevated levels of stress and coherent breathing can help. Since you benefited from time spent at high altitude you may benefit from the gentle light breath taught in the program. The technique is very nuanced and takes practice to get it right, so it’s good to have a guide of some sort. I am not sure spending a longer time at high altitude would be beneficial, I think it could place more stress on your body, but it seems shorter stays help, so maybe more regular short stays would be beneficial. The breathwork would have a similar beneficial effect on your CO2 receptors, but it takes regular practice of at least 15 min/day that you gradually build on with other techniques.

It may also be worthwhile trying a nebulizer or a salt inhaler to target the lungs.

On another note, I have an ND friend with long hauler who tried all sorts of things to get well, and one of the things that helped her the most was IV vitamin C. We are all different, so this may not be the cure for everyone, but there is also great research to support IV vitamin C for this. Infections can really deplete our nutrients so making sure you have adequate melatonin, glutathione, B vitamins, zinc, fish oil, CoQ10, etc, and get as much sunshine as you can on bare unprotected skin without burning. Astaxanthin is great as an internal sunscreen and can allow people to stay out longer in the sun without burning, it is also very anti-inflammatory. A nutrient dense, anti-inflammatory diet can also really help with recovery. I hope you feel better soon.

I have actually tried that altitude Science experiment with my own body and the effects didn’t last. Researched/contacted scientists and we couldn’t pinpoint why better at altitude. It seems counterintuitive as I recall, based on the disassociation (Bohr) curve of oxygen/red blood cells and altitude. It was a few years ago, fuzzy on details. But it sure was nice to be able to think up there.

I wonder what criteria they’re using to determine ME/CFS?

Finally ! Breaking Research ! ( PRIVATELY funded ! ) > https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=10GpwtQ_2Dc

This is very interesting to me. Since I developed MCAS I can’t take a normal deep breath. When I try, my breath “catches” about 5 or 6 times during the intake of air. Kind of like when you’re crying and you try to breathe in but the breath “stutters” all the way until your lungs are full. Like when people say or write, “She took a ragged breath.” I can’t make it stop, but after I’ve taken two or three of these ragged breaths, the next ones are normal. After I take these breaths until the stuttering stops and the intake is normal and smooth again, I realize my stomach muscles hurt like they’ve been held tight without moving for some time – squeezed as if I’m doing sit-ups (an exercise that I haven’t been able to do for about 20 years).

I have read Ari Whitten’s book about red light therapy and I have a full setup of red lights that I stand in front of for 10 minutes twice a day. It’s a mechanical anti-inflammatory instead of chemical and it supposedly works on the mitochondria. I believe it has helped me, along with all of my prescriptions and supplements. At least I’m still up and walking around for parts of each day.

When I’m experiencing a flare-up of MCAS, I find my gums are swollen, puffy and red. When I’m feeling fairly good, I go look in the mirror and find that my gums are not swollen. Instead, they have withdrawn way down around the teeth, exposing the tops of the roots below the enamel. Weird.

I easily get short of breath as my diaphragm, abdominals and accessory respiratory muscles (especially serratus and intercostals) are all knotted up which makes them very weak. It gets worse when it is cold and damp ( which it is right now in southern Australia), when it is draughty, when I’ve eaten too many carbs, when I have over-exerted myself or having an adrenal spurt. Also a virus can do it though I don’t often get one. At rest, my normal breaths are intermittently interspersed with a sudden deep inspiration followed by a long expiration (another words a deep sigh).

Cort, will you be doing a post on the various breathing strategies that might be able to help?

Has anyone encountered any methods on how to optimizing breathe while speaking? Or how not to disrupt breathing when projecting your voice?

I felt good this morning and then gave a short presentation. Immediately felt drained. A very common and frustrating experience. The more I think about this the more I think it likely has a disruptive breathing component, rather than just an exertional one.

Yes – a blog on that is coming up.

You can learn to breathe in through your nose even when speaking. It’s easy to hyperventilate while speaking otherwise.