Talk about being pioneering. Resa Pretorius and Douglas Kell have basically carved out a new field – microclots – for themselves. Their findings have gotten a lot of attention in long COVID, but Pretorius, in particular, has been finding microclots in all sorts of diseases for a decade. The fact that different kinds of microclots, as well as damaged platelets, blood vessel issues, and iron dysregulation have shown up in a wide variety of diseases (lupus, diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis, Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s disease), makes one wonder if they could have stumbled on an important factor in chronic illnesses in general.

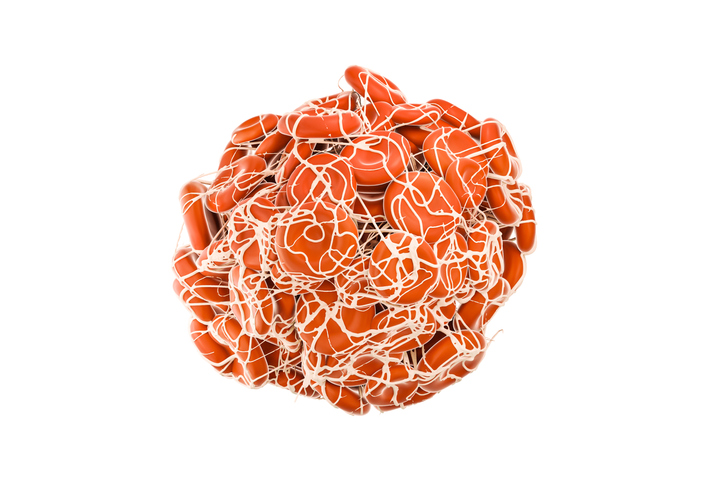

Check out the rounded symmetric nature of a normal blood clot. The one’s Pretorius and Kell are finding look like a bunch of spaghetti.

This all came about after she found what Kell vividly called, “horrible, gunky, dark” fibrin microclots at the bottom of her proteomic samples and decided to investigate. (Proteomic studies are regularly done. Did nobody else notice these?) Pretorius believes the strange shapes of these microclots are impeding their breakdown. Some, they report, are big enough to block the small capillaries feeding our tissues and result in a “defect in oxygen transfer at a capillary level”.

Kell proposed at the Oxford ME Conference that microclots are producing ischemic (low oxygen or hypoxic) events which turn really nasty when the blood flow returns. The sudden combination of oxygen-rich blood flowing into a hypoxic environment produces enormous amounts of free radicals and lots of localized damage (“reperfusion injury”). The antibodies they’ve found trapped in the microclots may signal that an autoimmune reaction to the strangely shaped “fibrinaloids” has taken place.

Why these microclots might be forming is not clear, but the potentially really good news is that because the body will slowly remove the microclots, if they can stop them from forming in the first place, normal blood flows should eventually resume and healing will take place.

The coagulation issue in COVID-19, though, has been nothing if not puzzling. Since the spike protein of the coronavirus induces clotting, it seemed a given that anticoagulants would help, but large-scale studies found them mostly to be a bust. Kell and Pretorius believe, though, the treatments didn’t go far enough. Since multiple problems exist (microclots, platelet activation, inflammation), they believe a multipronged treatment is needed to make a difference, and that’s what they’ve been doing in long COVID.

They’re not the only ones to propose that blood vessel problems lie at the heart of COVID-19 and/or long COVID. A recent review, “Endothelial dysfunction in COVID-19: an overview of the evidence, biomarkers, mechanisms, and potential therapies“, called the blood vessels, or endothelium, “the Achilles heel” for COVID-19 patients. COVID-19, the authors asserted, was a “microvascular and endothelial disease”, and included mitochondrial dysfunction in the long list of pathologies they believed blood vessel problems were causing.

Bruce Patterson puts the blood vessel injury first and foremost in his hypothesis, and his protocol is designed to protect them. Blood vessel problems are also central to Wirth and Scheibenbogen’s ME/CFS hypothesis. They’re the only ones I know of, thus far, that have linked the strange (and strangely disregarded) ACE2 and angiotensin findings in ME/CFS and POTS to blood vessel issues. Since the coronavirus enters into cells through the ACE2 receptor, one wonders if ACE2 receptor damage could provide a potentially important link between COVID-19, long COVID, ME/CFS, and POTS.

Two Treatment Trials

In an earlier paper (a preprint in Dec 2021, full paper Aug. 2022), Pretorius and Kell described the results of their multi-pronged attack on the clotting and blood vessel issues in long COVID. The authors warned that this approach, “must only be followed under strict and qualified medical guidance to obviate any dangers, especially hemorrhagic bleeding, and of the therapy as a whole.”

They reported, though, that the 24 participants in the trial resolved their shortness of breath, brain fog, concentration, and forgetfulness, and their fatigue was relieved over the 3-4 week trial. They also lowered their microclot scores by almost two full units (7.1 → 5.2) leaving them at near-normal levels.

Seven months later, they are back with another preprint and a bigger study, “Treatment of Long COVID symptoms with triple anticoagulant therapy“, that included 91 long-COVID patients.

As before, their triple therapy included Dual Antiplatelet Therapy (DAPT) (Clopidogrel 75 mg/aspirin 75 mg) once a day, plus direct oral anticoagulant (DOAC) (Apixiban) 5 mg twice a day, and a proton pump inhibitor (PPI) (e.g., pantoprazole 40 mg/day for gastric protection) was used over 3-4 weeks.

- Apixiban reduces coagulation.

- Clopidogrel and aspirin prevent platelet activation (aspirin by targeting the COX-1 receptor, and clopidogrel the P2Y receptor on platelets).

They divided patients up into ‘short’ long COVID (<6 months of persistent symptoms) and ‘long’ long COVID (<6 months of persistent symptoms). They had the patients fill out a “Patient Global Impression of Change” (PGIC) scale after treatment and a checklist of symptoms before and after treatment.

Patients with ‘short’ long COVID (symptoms less than 6 months) usually needed treatment for 2–4 months, while those with ‘long’ long COVID (symptoms more than 6 months), needed 4–6 months (or longer) of treatment.

Treatment Response

If an ultimate proof of a hypothesis is a successful treatment, their hypothesis is looking pretty good. We should note, though, that this 91-patient clinical trial was not placebo-controlled or randomized – two crucial factors that will need to be included in future trials – and included rather rudimentary symptom assessment scores.

Nice symptom improvement!

Still, some of the results were striking, with the authors reporting core symptoms like fatigue, cognitive dysfunction, muscle, and joint pain, shortness of breath, sleep problems, etc. clearing up in many patients.

When it came to overall effectiveness, the results continued to be positive. When patients were asked, “Since beginning treatment at the clinic, how would you describe the change (if any) in activity limitations, symptoms, emotions, and overall quality of life?”, their median score was 6: “Better, and a definite improvement that has made a real and worthwhile difference”.

If you took all the different responses and looked at the one in the very middle of the pack, that’s the median. This result means that as many people reported they were either:

- “better” and received “a definite improvement that has made a real and worthwhile difference”; or

- were a “great deal better” and received “a considerable improvement that has made all the difference”

Improvement meant having no symptoms.

as the number of people who reported they received lesser improvements (moderately better, somewhat better, etc.).

It’s hard to interpret this, though, as we don’t know how many people chose 6. If the most common response was 6 – and most people were from 5-7, these results would be impressive indeed. The fact that the median score was the second highest possible suggested that the responses were clustered around the upper end of the benefit scale.

The Gist

- Resia Pretorius Ph.d. has been calling attention to the dark, misshapen, gunky microclots and related problems (damaged platelets, blood vessel issues, and iron dysregulation) she’s been finding in chronic diseases for years. These clots are apparently hard for the body to break down and may be impeding blood flows to the issues.

- Over the past couple of years, though, with at least six papers under their belts, she and Douglas Kell have been publishing furiously on their findings in long COVID. Last year they published the results of a small clinical trial using their multipronged approach. Eight months or so later they’re back with more results from more patients (91).

- As before, their triple therapy included Dual Antiplatelet Therapy (DAPT) (Clopidogrel 75 mg/aspirin 75 mg) once a day, plus direct oral anticoagulant (DOAC) (Apixiban) 5 mg twice a day, and a proton pump inhibitor (PPI) (e.g., pantoprazole 40 mg/day for gastric protection) was used over 3-4 weeks.

- The symptom assessments seemed pretty rudimentary but the results were good. Symptoms such as fatigue, sleep, and cognitive problems reportedly resolved in many patients and when asked about their “global health” approximately 50% of the participants stated that they were at the very least “better” and had received “a definite improvement that has made a real and worthwhile difference”;

- The authors warned that this protocol should only be taken under the close guidance of a medical professional. Side effects were mostly minimal, however. Out of 91 participants, 75 reported bruising, 5 reported minor nosebleeds, 2 increased menstrual bleeding, and one person had a gastrointestinal bleed that required hospitalization and a 2-unit blood transfusion. The authors believed that the “relatively low bleeding risk” was due to the fact a hypercoagulable state was present that needed to be addressed.

- Apparently, because it took longer to treat the longer-duration patients, the authors also warned that delaying these treatments might “prolong the duration of pharmacotherapy and also increase the likelihood of permanent hypoxic tissue damage”. (Ouch!).

- They strongly urged that large, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials with objective endpoints be done as quickly as possible.

- The potentially good news is that the body will slowly remove the microclots. That means that if they can stop them from forming in the first place, normal blood flows should eventually resume and healing should take place.

- They also proposed that when long-COVID or ME/CFS patients rest, they build up “a cellular ‘reservoir’” that helps them feel better. When they exert themselves, that oxygen reservoir becomes depleted – leading to a “crash”.

- They also proposed that the autonomic nervous system issues in these diseases are caused by damage to the blood vessels.

- Their treatment approach has yet to be tested in ME/CFS, fibromyalgia, or postural orthostatic intolerance syndrome (POTS). All three diseases, however, show evidence of clotting, platelet activation, and/or blood vessel issues.

- A large placebo-controlled, randomized trial is clearly the next step

Apparently, because it took longer to treat the longer-duration patients, the authors also warned that delaying these treatments might “prolong the duration of pharmacotherapy and also increase the likelihood of permanent hypoxic tissue damage”. (Ouch!).

They strongly urged that large, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials with objective endpoints be done as quickly as possible.

New Ideas

They also proposed that when long-COVID or ME/CFS patients rest, they build up “a cellular ‘reservoir’” that helps them feel better. When they exert themselves, that oxygen reservoir becomes depleted – leading to a “crash”.

They also proposed that autonomic nervous system (ANS) problems result – not from a dysfunctional ANS system (at least initially) – but from blood vessel damage. They believe that damage to the blood vessels prevents them (or rather the smooth muscles lining them) from getting the signal to constrict them and send more blood to the muscles during exercise, or the brain during mental exertion. Unable to constrict the blood vessels enough, the body goes to its next best option – increase the heart rate to get the blood flowing more.

Next?

Pretorius and Kell have certainly done everything they can to open the door. Now the question is whether others are going to step through it and get these trials done. The elephant in the room, of course, is the RECOVER Initiative, which reportedly has allocated $172 million to clinical trials (!?). Thus far, it’s announced just one trial (Paxlovid) and is apparently working on a high-intensity exercise trial.

The sheer scale of the Phase III Paxlovid trial (1,700 people), though, demonstrates what a different world we’re in with the RECOVER Initiative. These kinds of trials should give us definitive results – something we’ve never gotten in ME/CFS. (By far, the biggest clinical trial in ME/CFS – the woeful PACE trial – included 641 patients and was littered with methodological problems).

There is a cost to them, though. With the median cost of a Phase III trial at $19 million, RECOVER may be committing around 10% of its entire clinical trials budget to this one huge trial.

The Paxlovid trial was announced at the end of October of last year and was expected to start recruiting at the end of January, but according to clinicaltrials.gov, it’s still not recruiting (?). Apparently, RECOVER has still not decided which other trials it will fund.

Evidence Building for Coagulation and Platelet Activation in ME/CFS, FM and Dysautonomia

This approach has yet to be tested in ME/CFS or fibromyalgia. Early studies did suggest that hypercoagulation was present in ME/CFS, but that effort faded. One study suggested that clotting problems are present in fibromyalgia. Other studies indicate that standing can produce hypercoagulation in people with orthostatic intolerance but not healthy controls. One review even concluded that “abnormal coagulation is an important component of orthostatic intolerance”. Then, just last year, an “unbiased” proteomic study zeroed in on proteins involved in clotting and platelet activation in postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS).

In their large overview, “The potential role of ischaemia–reperfusion injury in chronic, relapsing diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis, Long COVID, and ME/CFS: evidence, mechanisms, and therapeutic implications“, Pretorius and Kell noted that many treatment possibilities exist – most of which have been tried in these diseases.

Nothing like the comprehensive protocols Pretorius is using have been tried in ME/CFS, FM or POTS. Thus far, two studies from Pretorius’s group suggest that microclots are present in lower levels than in long COVID but are still quite present. One study reported:

“ME/CFS samples showed significant hypercoagulability as judged by thromboelastography of both whole blood and platelet-poor plasma. The area of plasma images containing fibrinaloid microclots was commonly more than 10-fold greater in untreated PPP from individuals with ME/CFS than in that of healthy controls.”

And

“We conclude that ME/CFS is accompanied by substantial and measurable changes in coagulability, platelet hyperactivation, and fibrinaloid microclot formation. The discovery of these biomarkers represents an important development in ME/CFS research. It also points to possible uses for treatment strategies using known drugs and/or nutraceuticals that target systemic vascular pathology and endothelial inflammation.”

The Pretorius saga continues. Pretorius, Kell, and Nunes just published a paper on clotting and cardiovascular issues in ME/CFS. A blog on that is coming up.

Update! – the ECHO program will produce a webinar on microclots in long COVID on April 12th.

Thank you Cort. Bummer that they’re not looking at controls in these studies thus far. Also, why is the hell aren’t they studying PEM as a symptom? It’s not the same thing as fatigue.

Yes, my guess is that this is a small research group and they’re doing the best they can. Pretorius’s findings have garnered a lot of interest – hopefully, we’ll see some nice large placebo-controlled, etc. trials sooner rather than later.

What can we do now? My brain. Always feels as if I can’t get oxygen 40 years. Can’t wait much longer.

I have lie flat ever since I got this when I was 23 I would go to doctors and lie down in room until doctor came.

It very well may not be getting the oxygen it should. That’s basically what the studies show. Unless you can get a doctor to give you a trial – which is probably doubtful – I think the thing to do now is wait for more results from other labs that will provide more evidence that this is real and prompt treatment trials.

There are supplements that people are trying. Check out the Coagulation Controversy blog for some of those

Cort, It sounds kinda’ nifty to state, “oxygen stores are quickly depleted in the cells, upon activity”. It has been decades since I studied Cytology, but where exactly is this extra oxygen? In the hemoglobin of erythrocytes? Seems like long term oxygen starved ME/CFS patients would adapt, and over time begin to produce more erythrocytes, and erythrocytes with much more oxygen carrying capacity.

I just asked chat got if Rapamycin and metformin can help heal endothial lining of cells and it said yes?

My this be why the person recovered from CFS who was on Rapamycin/

Rapamycin increases risk of sepsis

Still I took it and it worsened me.

My baseline is now more lowered after taking rapamycin 2 mg weekly

Oh no…I’m sorry.

I ordered a lot of it…:(

That is awful…how long ago did you stop?

I stopped one week ago. Took for three weeks. But my baseline kept lowering snd i kept crashing

So thought to give up on it

You can give it s try

Everyone is not same

yes, this is possible, and, interestingly enough Metformin may work best in a low dose:

https://www.healthrising.org/blog/2019/05/11/fibromyalgia-diabetes-metformin-chronic-fatigue/

Thank you very much..,, I couldn’t find the metformin dose.

I just started 500mg 2x a day…

Nobody knows about the right dose but in this small treatment study, metformin treatment with only 200 mg daily “increased AMPK activation, restored all biochemical alterations… and significantly improved clinical symptoms, such as pain, fatigue, depression, disturbed sleep, and tender points” in six people with FM. ((https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4742979/))

I was on low dose rapamycin for several months and it suppressed my immune system, allowing herpes viruses to reactivate. Had to go off it.

I must lay flat alot to recoop also. Before and after I go for a walk for example I lay flat for 20 minutes.

I think that is because we can’t get enough oxygen to the brain…

I approach my normal after I have been flat.. I think more blood flows to my extremities when I’m flat.

Interesting for me it is my brain ….

Mu guess is if they had done a smaller double blind placebo controlled study, they had more chance of getting such a part of money for the future if the outcome was so positive. And oh yes, fatigue is certainly not the same as PEM.

Yes, those are so much harder to do! Placebo-controlled trials are the next step, though.

If you go to the top of the page, there’s a link to the previous article they submitted. In that article they explain the way clots impact the way we react post exertion. It makes a lot of sense to me in light of my experiences during and after exertion.

I remember 35ish years ago, a researcher found abnormal shaped blood in PWM.E but he was disbelieved….

Cort, thank you for this! Do you know what the relationship between micro-clots and my high D-dimer results that landed me in the hospital would be? I had a stubborn infection of unknown origin, treated with antibiotics, but scans showed no clots. I’ve had weird blood results in the past that we’re always written off as lab errors. Thanks for all you do.

“written off a lab errors” – boy is that ever a red flag for an ME/CFS patient! I’ve had some high D-dimer results (which no one paid any attention to. D-dimer is a measure of clotting but Pretorius says that while it can be high in a person with microclots its not always and relying on it is a mistake in her opinion.

This is because D-dimer tests are a composite measure of coagulation: how much fibrinogen was present, how much was converted to fibrin clots, and how much was lysed or broken down are all packed into it. High D-dimer readings can indicate that increased clotting was present but cannot tell us anything about the key issue in Pretorius’s and Kell’s minds: how many clots were strangely shaped and have become resistant to being broken down.

As to the scans – my guess is that they would miss these clots. I believe she finds them in other ways.

In her most recent paper she proposes that herpesviruses are triggering clotting in ME/CFS.

Does anyone else have large red blood cells? That is the one thing that has came back consistently since I got sick….. large red blood cells…

They grow and grow I guess because my body isn’t replacing them well?

It is called macrociytic anemia the large red blood cells

you may want to check deficiency in folate an/or vitamin B 12. Both deficiencies make for large red blood cells

We don’t even have a semi correct number of me/cfs sufferers. I was diagnosed by retired physician in 97. Now that we have portals I see no mention of any chronic illness. Tho I thought I was a patient. Again I realize I mjust a number. My symptons are nt even real and I m 68 I do! I only know because my cardiologist sent my blood to Boston and they entered me in trying Repatha The report I got specified large dark blood cells . I ll dig that up and see if anything interesting shows up. I know the cardio guy spent none of his energy on Fibro,cfs,me. Once I like to fell out on floor doing bicycle test. I truly think he thought I was faking it.

Lab errors. So true. I’ve even had doctors tell me I don’t have stuff BEFORE the lab results come in.

“I have strep throat.”

“No you don’t.”

“Yes, please test.”

“Okay, but you don’t have it.”

Result: I do.

Previous doctor:

“I have strep throat.”

“I don’t see anything.”

“Look deeper.”

“Ooheww. I’ll write a prescription, but don’t use it unless you need it.”

I get the prescription on the way home and use it immediately.

Thanks for all the info, Cort!

Thanks for this Cort. I wonder if other ME patients have Leiden Factor V genetic markers for increased risk of blood clots? I encourage people to get inflammatory relevant DNA testing. It has made a big difference in my own understanding of my health. I used Genova Diagnostics many years ago wrt breast cancer but the Leiden Factor V result was the thing the docs there flagged as far more important. As to other commenters here, I too have fat red blood cells and odd lab results for rbc – a hereditary history for pernicious anemia, etc. My opinion is that this is a key area for ME.

The other really interesting flag that came up in the DNA results for me was a null result for a key gene that helps the liver clear environmental toxins. Explained migraines and huge reactions to fumes, smoke etc for me. Genetic testing should be for everyone, but especially ME patients.

I was tested for Leiden Factor V but don’t have it.

Please bring back the gist. This is way too much information and too complex for your target audience – people with brain fog and cognitive difficulties.

Whoa! I did it and forgot to put it in! It’s in now. 🙂

Thanks, Cort, for writing up and posting the gist.

The vaccine cause my me, not COVID. I got it 3 days after the shot and have p had it ever since. But since America is an evil country that prioritizes money over human life no one will admit it.

I have trialed Plavix with baby aspirin in three separate trials (about 2 weeks per treatment cycle). I was a little apprehensive since it is pharma but it seemed helpful.

I had some bumps (as others have reported), my suspicion is that the clotting factors are breaking up and an immune response ensues.

Oxygen does not enter the cells properly. Sticky blood, bloodflowproblems, vessels and red blood cells that are not easily deformable. Don’t forget low bloodvolume! If one of those are the cause, there is no autonomic dysfunction but compensation!

Therefore, there is air hunger and rapid heartbeat. If that is chronic, the immune system is suppressed and gets upset. The PH value in the blood will also be disturbed. Etc… the circle is then complete. Very interesting findings described above in the blog. They are on the right track.

What is alarming is that the spikes of the corona virus may be the culprit for developing microclots and inflammatory response of the blood vessels and other organs such as in the liver, ovaries and adrenal gland (known). It is known that the mRNA vaccine stimulates the body’s own cells to produce these spikes.

The nanoparticles with this information can end up anywhere in any organ after vaccination. This has been proven. And can stay there for a long time.It seems logical According to some immunologists every time you get vaccinated you run a higher risk of complications. They see high IL10 for a long time. A red flag.

This is a good article written by Prof Resia Pretorius. #TeamClots are very generous with their time & often appear on videos online to explain their views. I know Resia Pretorius travelled to New York, to explain her work & was in Rome last week, talking on Thrombotic Endothelialitis. She’s travelling to Santa Fe, New Mexico in August.

From what I see, they’re a very committed group, who understand how people suffering with chronic illness, after infections (like ME/CFS & long Covid) have been neglected & psychologised.

https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2022/jan/05/long-covid-research-microclots

This is not a slight on the author of this blog, but this paper has serious, serious issues with it’s methodology, especially in the platelet aspect. I really hate being so pessimistic but I don’t want laypeople to read this study and instantly jump on the daily antiplatelet therapy bandwagon.

Firstly, no control patient group — there is absolutely no reason why a control patient group could have not been in this study. If there is enough funding to enroll 91 long COVID patients, split it down the middle with controls. In addition, no details about whether patients were blinded or randomised.

There is absolutely no quantification of platelet function, and where there could be important information about platelet functioning, through the haematological parameters they measured, they authors have excluded.

The spreading assays are particularly bad – there are no agonist, so you are working on the presumption that long COVID patients prior to have circulating primed, and/or activated, platelets…. but platelets activate if they are exposed to air, temps below room temperature, tissue factor, etc. The use of “representative images” is a terrible practice, as there is no form of randomisation, and therefore, is ripe for cherry picking.

Where are the absolute basics, that nearly every lab has the means to access, at low costs and a rapid throughput, like flow cytometry? LTA? Aggregation studies? The authors even mention that they used flow cytometry in their methods – perhaps I am being blind, but where is it?

Anyone funder worth their salt would be very, very concerned looking at these results, and I am of the opinion that studies like this, preprint or no, only perpetuate problems with funders not taking ME research seriously.

Thanks so much for pointing out the limitations of the study.

While I agree that we need a placebo-controlled study, I don’t quite know that its quite as simple as splitting the patient group in half and adding healthy controls. Pretorius presumably has easy access to patients but she would have to find the HC’s – never an easy task I have been told – begin a heavy duty triple anticoagulant trial in them (who would agree to such a thing?), and pay for their meds. That might just be too much for an office that doesn’t regularly run clinical trials.

We certainly need haemtological measures though. They have provided them in other studies – https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36131342/ – https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36131342/ Again, I wonder if they just didn’t have the funding to do that? or if something else was going on. It’s a pity they weren’t presented – particularly given this is apparently a pretense regimen – which they warn against anyone doing without the supervision of an expert.

Their earlier trial did find that a “decrease of both the fibrin amyloid microclots and platelet pathology scores”. (Using their own scoring system).

I agree this is a preliminary finding – we need larger, more methodologically rigorous studies to know what’s what. They also clearly need to produce more physiological data in order to enroll other researchers in their findings. Thanks for pointing that out.

I wish you were so critical when the pfizer and moderna vaccine came up Cort 🙂

Probably in a first step, Pretorious et al. focused on testing treatment intervention to help their patients seeking help, and find what treatment could work in principle, which will need to be placebo controlled in larger trial.

Could it be–something else? While checking abnormal cortisol levels, and then coming down with osteoporosis and pre-diabetes, seemingly out of nowhere, my endocrinologist give me an electrophoresis test. This is not a common test, but mine showed a spike in a certain monoclonal IgG protein. This M-spike was relatively low, but still does raise my risk of developing some sort of blood or lymph problem. I was told that seeing a small M-spike is not rare in older people. One of the disorders that could develop was Multiple Myeloma. Since MM affects the lymph fluid and consequently the blood flow making it ‘thicker, I wondered how many others might have low levels of this M-spike. Many of the (beginning) symptoms are quite similar to those of ME/CFS and L-Covid, especially fatigue, neuropathies and abnormal labs.

I have heart disease (blocked arteries) and there are things that the heart disease community are doing that have helped my ME/CFS. Taking baby aspirin helps, taking Plavix helps (although I am not taking this now for other reasons), foods that heal the endothelium helped such as pomegranate and high nitrate oxide foods like leafy greens helps. There are tons of studies about high nitrate foods and pomegranate healing endothelial cells.

So you mean you taking clopidrogel and baby aspirin for your heart issues. helped your CFS Symptoms

Great blog. As an ME/CFS patient, Covid vaccination seems to have permanently left me with the new symptom “shortness of breath”.

So I’d be interested in trying this treatment to try and remove the symptom “layer” that may presumably relate to spike protein vaccination. (I think one professor in Germany has speculated post-vac may relate to accidentally injecting the vaccine into a blood vessel not muscle tissue).

But which doctor (and medical discipline) in Germany would be the right one to do such a medically supervised trial with me? I’d bet my GP would think it too dangerous. And what would “strict and qualified medical guidance to obviate any dangers” mean in practice – does doctor need to do any specific blood tests during exercise, would he need to be a haematologist, or is it more about recognising potential bleeding events and which hospital to go to in that care? Suggestions welcome.

I’ve dabbled a bit in Nattokinase and kind of felt “oxygenated” by the first few doses, but then wasn’t sure about possible side effects (there could be, according to LongCovidPharms blog and the comments on it, some Herxheimer or MCAS reactions; so I might come back to it after the pollen allergy season).

Cort, as Nattokinase is also supposed to adress microclots, would you know if Pretorius and Kell tested it or what their opinion is on Nattokinase?

Does anybody else feel like we keep going in circles? Clotting issues in CFS were discusses over 10 years ago. There was a little bit of buzz then it dies down. Then we talked about viruses for a few years then it died down. and on and on it goes. Now we are back to clotting issues again.

Any given issue (clotting, or virus, or ANS dysfunction) needs to be FULLY investigated to arrive at a definitive yes/no answer, and start moving forward.

I can’t be the only one who notices that we keep re-investigating the same issues and never having a definitive conclusion.

Is there no way to have the CFS researchers create/join a central organization that coordinates CFS research carried out by the various CFS researches so that research is conducted in a coordinated fashion and progresses linearly rather than in circles?

So much agree with this comment! We are in desperate need of just following through on findings properly and keeping following the trail that the evidence points to until we either get definitive answers or technology and science limits stop us going further. Enough with all the piece meal little forays into the same stuff. I guess it’s lack of money! All the more reason for collaboration and bringing funding together.

Exactly. With such a lack of funding, I believe the researchers should be more focused, rather than conducting research that is known, ahead of time, to not have enough power (statistically speaking) to yield a definitive answer.

There are not that many scientists conducting research on CFS. They should consult with one another and choose ONE issue that they believe is the most promising. Then for that year (ex 2023) all research funding and efforts should be focused on that one issue, until a clear yes/no conclusion is arrived at.

Then in 2024, repeat the same process with a second issue. And so on and so forth.

Progress may be slow…but at least there will be progress. Currently, ALL issues remain as a possible cause/contributor to CFS. In over 20 years of research, we have not definitively ruled in or out a single factor. All that time, and precious funds have been wasted.

When one has limited resources (in this case limited funds), one needs to be laser focused.

Cort, you are often in contact with all these researchers. Isn’t there a way to entice them to form a committee where they could discuss ways to focus their research on one issue at a time until it is ruled in or out?

Yes, it’s very frustrating. We have so many hypotheses and only a limited amount of funding to distribute amongst them. No one seems to have the courage to *disprove* any of those hypotheses, so we are in perpetual limbo with no clear path forward.

I’m puzzled as to why nattokinase and or serrapeptase are not included in these trials. Is it because big pharma money needs to be involved?

I have been taking Plavix 75mg and aspirin 81mg for 5 years . It hasn’t helped my me/CFS at all.

I’ve had itchy red spots on and below my skin since first having Covid, then in reaction to the jnj vaccine. The itching and extent has lessened over time. I’m taking antihistamines to reduce itching and at first thought I had a mast cell over-activation.

I found the closest thing in appearance and description to the spots are called angiokeratomas, found in Fabry Disease. It’s caused by a hereditary lack of alpha galactosidase to break down GL3 lipids. Lipids then accumulate on vascular endothelial cells causing micro clots.

Alpha galactosidase deficiency can be measured with a blood enzyme assay test which I will request. In the meantime I’m taking bean-aid, an off the shelf digestive supplement that contains alpha galactosidase. Occurrence of spots/ microclots have lessened but I’m taking too many other supplements to know what actually helps.