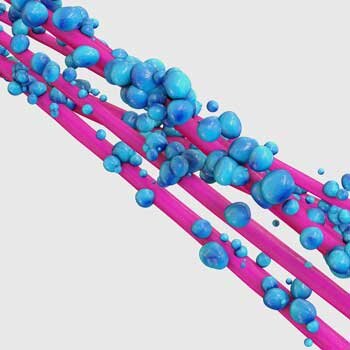

Our guts are teeming, just teeming, with bacteria that provide many useful functions. They break down food, knock down pathogens, regulate the immune system and hormone release, and even affect brain functioning. Several serious diseases including cancer, diabetes, and rheumatoid arthritis have been associated with unhealthful assemblages of gut bacteria.

The solution seems clear – pound the gut with good bacteria, get it back into balance, turn the immune activation off, and who knows, maybe even conquer ME/CFS and fibromyalgia (FM).

Certainly, it’s worked for some people but for many others, it hasn’t. That’s really no surprise, nothing works for everyone in these diseases. The surprise comes from people who have experienced really negative effects from what appear to be good bacteria. How could that happen?

Two recent studies suggest that using probiotics to replenish our gut flora may be less benign than we think and underscore the realization, that the gut, like virtually every other part of the body, is more complex than we knew.

The Studies

In Personalized Gut Mucosal Colonization Resistance to Empiric Probiotics Is Associated with Unique Host and Microbiome Features. Israeli researchers did something rather simple – something which in retrospect, probably should have been done long ago. They took 25 healthy people and used endoscopy and colonoscopy to assess the bacteria found in their upper and lower gut areas.

Then they gave them a standardized dose of probiotics twice a day (Lactobacillus acidophilus, L. casei, L. casei sbsp. paracasei, L. plantarum, L. rhamnosus, Bifidobacterium longum, B. bifidum, B. breve, B. longum sbsp. infantis, Lactococcus lactis, and Streptococcus thermophilus) and measured the bacteria in the different place in their guts. Their stools were sampled throughout the study.

Resisters and Persisters

Two groups emerged: the persisters – a group whose guts accepted the new bacteria and changed in a positive way, and the resisters whose guts rejected the bacteria and didn’t change at all. Their interest piqued, the researchers then transferred the bacteria from the resisters and persisters into mice with no gut bacteria and then gave probiotics to them.

The same thing happened – indicating that the bacterial makeup of a person’s gut, at least in part, determines whether probiotics will help them or not. Something about the ecological makeup of the resisters’ bacterial populations made it impossible for the good bacteria to catch hold.

The Israeli researchers didn’t stop there. Adding the participants’ gene expression – which genes were active or not in the blood – into the mix, they hit a home run. Even though they were healthy, the resisters displayed an autoimmune gene signature that interfered with their guts’ ability to accept good bacteria. The takeaway – If you’re not benefiting from probiotics both the state of your immune system and your gut bacterial makeup may be responsible. The problem may be worse than that, though.

Another Israeli study “Post-Antibiotic Gut Mucosal Microbiome Reconstitution Is Impaired by Probiotics and Improved by Autologous FMT” found that a standard practice among some doctors – to first wipe the gut clean with antibiotics and then repopulate it with bacteria – was not helping.

The researchers wiped out the guts of three sets of people, then recolonized one group with fecal transplants of their own gut bacteria, another with probiotics, and the last they let recover naturally. The guts of the participants recolonized with transplants of their own fecal material recovered at lightning speed: within a week their gut composition was back to normal. The participants whose guts were allowed to heal naturally took about three weeks to return to normal, but the people taking probiotics took up to six months for their gut composition to return to normal, and some of them were still not normal even then.

Any ecologist (the gut is an ecological system) probably wouldn’t have been surprised at this result. Trying to reinstitute a complex ecosystem by giving a few species a boost can allow them to block others from establishing themselves, resulting in a low-diversity ecosystem and that’s basically what happened.

Even months later the guts of probiotic-receiving participants still had low bacterial loads and dysregulated gut ecosystems. It turned out it was far better to let mother nature take its course and allow the gut ecosystem to repopulate naturally.

“We’re talking about an entire rainforest in the gut that’s being affected in different ways by different antibiotics, and you can’t just patch that up by giving a probiotic. Because, let’s face it, a probiotic has maybe seven or eight strains. There’s a lot in the literature about some of these bacteria being beneficial, and it’s interesting, but they are really some of the few microbes in the gut that are fairly straightforward to culture. And I think that drives the probiotic industry more than it would like to admit.” Allen-Vercoe

It’s possible, then, that taking probiotics when you have a dysregulated gut ecosystem could help, but it could also throw things off. One wonders if some of the negative responses to probiotics result from adding good bacteria into the wrong ecosystem. Laboratory studies suggest that factors secreted by the Lactobacillus species often found in yogurt preparations might actually be inhibiting other bacteria from colonizing. The probiotic species found in store-bought preparations, it should be noted, are not necessarily the ones that are needed – they’re the ones easily grown in the lab.

The Poop on Stool Samples

But then came some more bad news. Stool samples or fecal transplants may not be the cat’s meow either. The bacteria actually found in the gut (obtained through endoscopies and colonoscopies) differed markedly different from those found in stool samples.

The stool samples failed at the test of predictiveness as well. While the gut mucosal samples (and the gene expression results) could be used to determine whether someone was a “resister” or “persister” – the stool samples could not.

It turns out that the most widely used snapshot of the gut – the stool sample – is actually the least representative. Gut mucosal sampling – a sampling of the bacteria found in the gut lining via two invasive procedures (endoscopy and colonoscopy) is the only way to accurately determine the state of your gu.

There are, of course, other less invasive ways to assess the effectiveness of probiotics or fecal transplants. Improvement in symptoms: gut issues, fatigue, mood, etc. could indicate that whatever gut manipulation you’re doing is working and the news in these studies wasn’t all bad, though.

The fact that the probiotics were better able to colonize the guts of people with lower levels of good gut bacteria suggested that people with poor gut flora – such as people with ME/CFS – might have a better chance of benefiting from probiotics. (That has to be considered alongside the fact that people with autoimmune tendencies tended to resist probiotic colonization.)

There is certainly a place for probiotics in medicine. A recent review of two ME/CFS probiotic studies concluded that probiotics had a “significant effect on modulating the anxiety and inflammatory processes “. Repeated studies have found them helpful in irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), metabolic syndrome, diabetes, and obesity as well.

The situation is just a bit more complex now. That we’re not at the prescriptive phase of treating most diseases with probiotics isn’t exactly shocking, either. ME/CFS researchers Ian Lipkin and Maureen Hanson, a member of Simmaron Research’s Scientific Advisory Board, have been tackling the gut, and both have been wary about providing any prescriptions for gut manipulation in ME/CFS yet. Given the huge differences in gut bacteria from person to person, a personalized approach – matching personal gut weaknesses with specific probiotics – was always probably going to be necessary. Ian Lipkin alluded to this earlier:

As we learn more about ME/CFS, we are beginning to define subtypes. This is critical to understanding how people become ill and developing practical solutions for management. The challenge is not unique to ME/CFS. It is representative of the Precision Medicine initiative that is sweeping clinical medicine and public health. Just as there is no one cause or cure for all cancers, all forms of heart disease, or all infections, there will be more than one path to ME/CFS and more than one treatment strategy.

The good news is that gut research is exploding in ME/CFS. Ian Lipkin introduced a gut-associated subset (ME/CFS patients + IBS) with unique metabolic problems, and remarkably enough, found that differences in gut bacteria were more effective than metabolites in differentiating people with ME/CFS from healthy controls.

Derya Unutmaz – whom Lipkin is now collaborating with – has found strong evidence that T-cells associated with bad bacteria are playing a role in ME/CFS. Plus, a recent hypothesis put forth by Jonas Blomberg proposes that a leaky gut may set the stage for ME/CFS.