Check out Geoff’s Narrations

The GIST

The Blog

Maeve’s ME/CFS ultimately left her unable to eat or drink and lacking proper care she slowly starved to death. The coroner’s conclusion that “There is no known treatment for ME“, missed the point entirely. So have others who’ve implied that Maeve died of myalgic encephalomyelitis (ME). Maeve was not asking for treatment – she was asking to be kept alive. Other people have been as sick as Maeve and survived. Other people have even been as sick as Maeve and fully recovered.

The difference is that they got care – and it wasn’t specialized ME/CFS care or care that could not have been done in a hospital or even at home: they received the kind of care that people who cannot eat or drink get as a matter of course, and that made all the difference.

THE GIST

- An inquest into Maeve Boothby-O’Neill’s tragic death in 2021 has brought the elephant in the room – the plight of the severely ill ME/CFS patients – into sharp focus.

- Maeve’s ME/CFS ultimately left her unable to eat or drink and lacking proper care she slowly starved to death. The coroner’s conclusion that “There is no known treatment for ME“, missed the point entirely. So have others who’ve implied that Maeve died of myalgic encephalomyelitis (ME). Maeve was not asking for treatment – she was asking to be kept alive. Other people have been as sick as Maeve and survived. Other people have even been as sick as Maeve and fully recovered.

- She had herself admitted to the hospital three times in an attempt to resolve her malnutrition. After an attempt to use a nasogastric tube (used at perhaps an inappropriately high volume) failed (she vomited) during her 3rd visit, the hospital – which was warned she was slowly starving to death failed to intervene further.

- Other feeding options (NJ, PEG, PEJ tubes, total parenteral nutrition (TPN)) were not attempted. Some of them were rejected, rather bizarrely, because the doctors felt they would be “unsafe”.

- it’s hard not to conclude that her doctor’s preconceptions of her illness colored their treatment of Maeve. Several of her doctors at the hospital concluded she did “not have a medical disease”. “

- Despite the hospital’s assertion that it did not fail its “duty of care”, nor that it did not miss opportunities to treat her, the coroner disagreed. She concluded that a healthcare professional should have been appointed to coordinate Maeve’s care and Maeve should have received a feeding tube after her second admission to the hospital.

- The coroner’s decision to file a “Prevention of Future Deaths Report” is potentially a landmark decision as this is the first time an ME patient’s death has provoked such a response. It indicates that she believed Maeve’s death was preventable, that others are at risk, and hopefully sets the stage for institutional change.

- Three years after her death, though, the medical director of Royal Devon University Healthcare NHS Foundation Trust reported that nothing had changed, that no care pathways had been created for the severely ill, that no beds were available for them either regionally or nationally, and that no work was underway to create care pathways.

- Most people in the ME/CFS community didn’t have to look far to conclude that Maeve’s death was preventable. Whitney’s Dafoe’s blog, “Drops From The Well of Suffering: Honoring Maeve Boothby O’Neill”, Whitney described undergoing a similar situation – with a very different result – when he was treated with intravenous nutrition.

- Published the year before Maeve died, Speight’s 2020 paper, “Severe ME in Children“, clearly outlined the dire problems with food intake that can occur and how helpful tube feeding can be. Speight wrote that “the abdominal pain may be so severe as to interfere with nutrition” and that “problems with eating and drinking…may necessitate tube feeding”. He described three very young (13-year-old) patients for whom early tube feeding allowed them to survive all of whom fully recovered later.

- Maeve died a death – a slow death from starvation – that one can hardly believe would happen in our modern age. How could such a thing occur? A lack of institutional awareness regarding the needs of the very severely ill.

- The UK is not alone in this. A Norwegian survey found that when “help” arrived, it often proved hurtful as nurses sometimes exposed the severely ill to damaging stimuli that further exacerbated their condition.

- Writing from the U.S. in 2021, Amber asserted in, “We are Failing People with Very Severe ME/CFS“, that the responsibility for getting better support for the very severely ill lay in the community that understood them best – the ME/CFS community.

- Indeed, up until 2021, no major ME/CFS reports warned that the severely ill may need intravenous feeding to survive. Since then progress has been made. The 2021 paper “Caring for the Patient with Severe or Very Severe Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome” and Mayo’s 2023 “Diagnosis and Management of Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome” confronts the malnutrition problem head-on.

- The severely ill are also slowly showing up in scientific journals. The Health Care journal in 2020 devoted an entire edition to them. Several journal articles in the past several years have focused on the experiences of the severely ill. The Open Medicine Foundation’s Severe ME/CFS Big Data project explored the physiology of the severely ill. (A blog is coming up on that).

- In an essay at the end of the blog, Christian Kull likens the severely ill to the problem of Schroedinger’s cat in quantum physics, where every attempt to analyze the cat changes it. In his story of his severely ill son’s dilemma (below), Kull speaks to the “tension” between the need for medical care and research and the potential harm it can cause people with severe ME.

- Kull writes “Unlike Schrödinger’s cat, which is both dead and alive, we know that while people affected severely by ME/CFS are missing, they are very much alive. They suffer from a terrible illness and the worst quality of life. They are in need of all the attention they can get, for research and for individual care – without the noise, the prodding, the poking, and the stress. We need to observe the cat without opening the box.”

Maeve’s Story

Maeve first became ill with ME/CFS when she was 13. Over time, she became sicker and sicker until she became unable to eat or take in liquids. Despite her intense suffering, Maeve clearly wanted to survive. Four months before she died at age 27, she wrote her doctor:

“Dear Dr Shenton, I know you are doing your best for me, but I really need help with feeding. “I do not understand why the hospital did not do anything to help when I went in. I am hungry, I want to eat. I have been unable to sit up or chew since March and the only person helping me eat is my mum. I cannot get enough calories from a syringe. Please help me get enough food to live.”

She had herself admitted to the hospital three times in an attempt to resolve her malnutrition. After an attempt to use a nasogastric tube (used at perhaps an inappropriately high volume) failed (she vomited) during her 3rd visit, the hospital – which should have understood that she was slowly starving to death yet failed to intervene further.

Other feeding options (NJ, PEG, PEJ tubes, total parenteral nutrition (TPN)) were not attempted. Some of them were rejected, rather bizarrely, because the doctors felt they would be “unsafe”. Blackburn, the nutritionist, noted that if she had been diagnosed with an eating disorder she would have had a better chance of getting a bed at a specialist unit.

The hospital had been warned. Stephen Blackburn, a dietician warned after Maeve’s second admission that “her outlook seems quite bleak”. After she was released after her 3rd admission he concluded that without specialist care “a tragic outcome” would soon result.

The UK’s health system is a mess right now and times are tough, yet it’s hard not to conclude that her doctor’s preconceptions of her illness colored their treatment of Maeve. Several of her doctors at the hospital concluded she did “not have a medical disease”. Dr. Roderick Warren, a consultant on her case, stated that “there was not enough evidence to conclude the illness is a physical one” (as if that matters when a person is starving to death). Even after Maeve died Warren was not able to conclude that ME was a physical condition stating “I do not know what the cause of ME is. Therefore I’m not able to say if it is or is not a physical condition.”

Despite the hospital’s assertion that it did not fail its “duty of care”, nor that it did not miss opportunities to treat her, the coroner disagreed. She concluded that a healthcare professional should have been appointed to coordinate Maeve’s care and Maeve should have received a feeding tube after her second admission to the hospital. She reported:

“In making the findings I have, I hope that important lessons for future treatment of ME can be learned from her death.. No doubt with the benefit of hindsight things will be different in many respects.”

The coroner’s decision to file a “Prevention of Future Deaths Report” is potentially a landmark decision as this is the first time an ME patient’s death has provoked such a response. It indicates that she believed Maeve’s death was preventable, that others are at risk, and hopefully sets the stage for institutional change.

Andrew Gwynne, Minister for Public Health and Prevention, stated that Maeve’s death was a “heart-wrenching example of a patient falling through the cracks… Maeve and her family were forced to battle the disease alongside the healthcare system which repeatedly misunderstood and dismissed her.”

Three years after her death, though, Dr. Helmsley, the medical director of Royal Devon University Healthcare NHS Foundation Trust reported that nothing had changed, that no care pathways had been created for the severely ill, that no beds were available for them either regionally or nationally, and that no work was underway to create care pathways. The implication was that the very severely ill were beyond the ability of the National Health Service to support them.

As we’ll see below, though, while it is not easy to care for the very severely ill, hospitalization or special units – while helpful – are not always required. Everything that needs to be done to keep them alive can often be done at home. Concerning special units, Dr. Shepherd of the ME Association called for a “small number of specialist ME/CFS centres with dedicated hospital beds”.

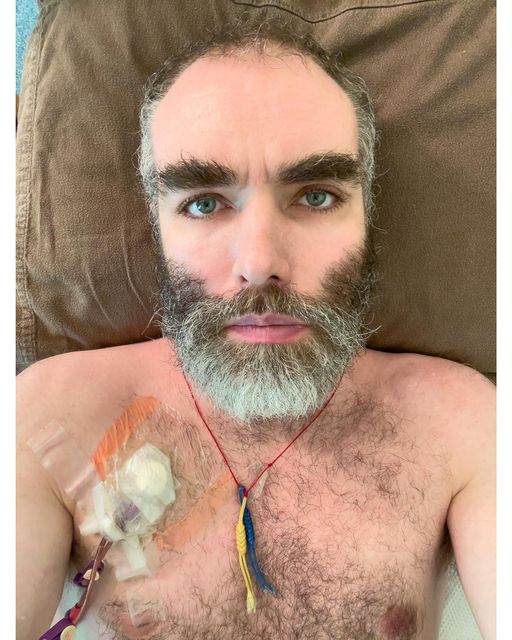

Intravenous feeding saved Whitney Dafoe’s life. His published story provides the most complete account of severe ME/CFS yet

A Preventable Death

Most people in the ME/CFS community didn’t have to look far to conclude that Maeve’s death was preventable: we already had Whitney’s Dafoe’s well-known story. In his blog, “Drops From The Well of Suffering: Honoring Maeve Boothby O’Neill”, Whitney described undergoing a similar situation – with a very different result.

“When my stomach stopped tolerating food or water, I started starving to death. I lost 35 lbs (16kg), leading to a body weight of 115 lbs (52.1kg) and I am 6’3″ (190.5cm) tall . But my doctors stepped in and got me Total Parenteral Nutrition (TPN) in time to save my life.”

Dr. Nigel Speight described three cases where tube feeding saved lives and even ultimately lead to recovery. (From Bristol Watershed Youtube Meeting)

Whitney has been kept alive with intravenous nutrition for years now, and he’s not the only one to benefit from it.

Published the year before Maeve died, Speight’s 2020 paper, “Severe ME in Children“, clearly outlines the dire problems with food intake that can occur and how helpful tube feeding can be. Speight wrote that “the abdominal pain may be so severe as to interfere with nutrition” and that “problems with eating and drinking…may necessitate tube feeding”.

He described three very young (13-year-old) patients for whom early tube feeding produced excellent results. (A Norwegian survey found that people who became ill at a younger age were over-represented amongst the very severely ill.)

Patient #1: “Tube feeding was started early to good effect, amitriptyline and carbamazepine were tried for her pain, and immunoglobulin was given. After 12 months, she began to improve, and then her rate of improvement accelerated. By the end of two years, she had made a full recovery, and has never subsequently relapsed.”

Patient #2: “My next mistake was to give in for too long to her objections to nasogastric tube feeding. Once I finally persuaded her, life became much better for everyone. Because of the evidence that immunoglobulin might be an effective therapy, she was treated with this by intramuscular injection, monthly, for 12 months. She made a very slow recovery, and tube feeding was stopped after 3 years. She continued to recover and 20 years later has a full-time job, and is operating at 95% of normal.

“Patient #3: “Over subsequent weeks, she lay motionless and in severe pain, and her breathing was so shallow that I was afraid she was going to die. Tube feeding and immunoglobulin were resorted to early on…At nine months, I changed the clarithromycin to doxycycline, on the grounds that it was just possible that she might have a form of Lyme disease. From that time, she steadily improved, and within 12 months, she had recovered completely. At follow-up 12 years later, she had suffered no relapses and was the healthy mother of a healthy child.”

Maeve died a death – a slow death from starvation – that one can hardly believe would happen in our modern age. How could such a thing occur?

Lack of Institutional Awareness

The difference with Dr. Speight’s patients and Whitney was that they had access to good medical care, and therein lies the problem: the very severely ill are usually at the mercy of their local medical establishment which often doesn’t know how to support them.

Guidelines for treating diabetes, heart disease, etc., are known to every doctor no matter where they practice, but that’s not true with very severely ill ME/CFS patients. Their fragility, sensitivities, and even just their diagnosis can set them a world apart. Dr. Klimas recently reported how an ME/CFS patient with dangerously low blood pressure was sent on her way without treatment by emergency room staff. Did Maeve’s ME diagnosis lead the hospital to not pay close enough attention to a young woman who was wasting away?

A lack of institutional awareness regarding how to properly support the very severely ill ME/CFS patient pervades the medical establishment. The UK is not alone in this.

A Norwegian survey found that many of the very severely ill could not turn themselves in bed or communicate. Pain, nausea, fatigue, and brain fog were constant companions. Despite this, when “help” arrived, it often proved hurtful as nurses sometimes exposed the severely ill to damaging stimuli that further exacerbated their condition.

Writing from the U.S. in 2021, Amber asserted in, “We are Failing People with Very Severe ME/CFS“, that the responsibility for getting better support for the very severely ill lay in the community that understood them best – the ME/CFS community.

Asserting, “We need to change this narrative”, she noted how little information even the ME/CFS community had provided on the severely ill. Severe malnutrition – probably the most dangerous situation these patients face – was often unaddressed. She concluded that “in the absence of accurate information about very severe ME/CFS, many physicians conclude a malnourished patient must have an eating disorder and, therefore, a psychiatric condition”.

The “Beyond Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome: Redefining an Illness (2015)” report from the

National Academies of Sciences contained a section on pediatric ME/CFS but not on the very severely ill. The U.S. ME/CFS Clinician Coalition’s 2020 “Diagnosing and Treating Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome” does not mention the severely ill. The Clinician Coalition’s 2021 “ME/CFS Treatment Recommendations” does not indicate that tube or parenteral feeding might be required. While the Clinician Coalition provides helpful resources on mast cell activation, Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome and hypermobility, orthostatic intolerance, pregnancy, surgery and anesthesia, and long COVID, it has yet to produce one for the severely ill.

Similarly, the 2021 “Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome: Essentials of Diagnosis and Management“, published in the Mayo Clinic Proceedings, notes the energy limitations and sensitivities of the severely ill but does not mention the possibility of malnutrition. (It does provide links to Speight’s paper, however.)

The UK’s 2021 NICE Guideline’s surprisingly complete overview of the severely ill misses the point when it comes to nutrition. The Guidelines note that the severely ill are often “unable to eat and digest food easily and may need support with hydration and nutrition” but does not suggest that tube feeding may become necessary to save a life.

Progress

Progress has been made since Maeve passed. The 2021 paper “Caring for the Patient with Severe or Very Severe Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome“, states “tube feeding may be required to ensure nutrition and to conserve the patient’s energy”, and “If necessary, intravenous feeding may be required as a last resort”. Similarly, Mayo’s 2023 “Diagnosis and Management of Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome” confronts the malnutrition problem head-on.

“Malabsorption and malnutrition due to gastrointestinal and immunologic disease are common in severe-presenting patients. Anorexia nervosa is often incorrectly diagnosed in these patients, especially when presenting with malabsorption. Parenteral nutrition may be required; in such cases, refeeding syndrome should be considered. Patients with severe ME/CFS may also require gastric tube feeding and intravenous administrations to avoid critical electrolyte imbalances, requiring total care in compatible homes or in nursing facilities.”

Research

Like Schrodinger’s cat the very act of assessing the severely ill can alter them physiologically.

The Dilemma of Caring and Doing Research for Severe ME/CFS Patients

by Christian Kull

“Bedbound people affected by very severe ME/CFS live out of sight, like Schrödinger’s cat. That cat is in a closed box, simultaneously alive or dead, until the observer opens the box and sees it in one state or the other. Schrödinger’s thought experiment from quantum physics provides a powerful analogy for describing the paradoxical situation in medical contexts where observation and intervention can impact the condition being studied or treated. In the case of bedbound sufferers of ME/CFS, they are also out of sight and unknowable, as the act of observing might affect the state of their health.

Patients affected by very severe ME/CFS live in a box that is their bedroom, curtains drawn, lights out, earmuffs on, with little contact. The observers are the carers and doctors wishing to help ME/CFS patients, and medical researchers wishing to understand this illness. The interventions that they wish to do to evaluate the state of the patient contribute to making things worse: drawing blood, asking questions, transporting to medical facilities. There is a tension between the need for medical observation and the potential harm it can cause.

This paradox – that medical attention and care might make things worse – is caused by the pernicious nature of the illness, particularly its chief symptom PEM, or post-exertional malaise. Sufferers have a very small, limited quantity of energy available, and passing over that limit leads to feeling worse for days afterwards. Very severe cases merit urgent attention and care.

Yet, paradoxically, they are (1) the most invisible, the fully missing, and (2) the most at risk of interventions that degrade their condition. Among very severe cases of ME/CFS, a sufferer’s limits are so low that they can be exceeded by physical action like chewing a meal, stimulation from noise or light, or emotional stress (see this excellent autobiographical video called “The prison of M.E.”). In some cases they may not even be able to communicate, or only by a nod or a very short text message.

Due to PEM, well-intentioned medical interventions for patients have commonly made things worse, sometimes for a day or two, sometimes for long periods (Dafoe 2021; Hoffmann et al. 2024). My 20-year-old son has been laid low by ME/CFS. The trigger, around his 18th birthday, was an unremarkable Covid-19 infection followed a few weeks later by full anesthesia during a knee surgery for a ski injury. Initially, for over a year, he was functional but not well, for instance struggling to recover from knee physiotherapy sessions or too tired and nauseous to ski.

Then, back from college a year ago in summer, step-by-step his state declined to the point that he took to bed full-time. In early autumn, when he could still occasionally dig in his energy resources to talk and move around, a battery of medical visits (including the long-covid clinic and diverse specialists to exclude other possible causes) repeatedly degraded his state.

Part of it was physical exertion: sitting or standing up, getting to appointments, neurological walking tests. Part was the body’s reactions to excess physical stimulation: bright lights, sounds, bumpy medical transport, loud MRI machines, blood tests. And on top there was the mental exertion of filling forms, answering questions, and the heavy emotional stress of sometimes dealing with disbelief and dismissal (Sedgewick 2022, Monbiot 2024).

A particularly traumatic incident was being seen at a neuropsychology clinic, where the professor in charge berated my son for coming in a wheelchair, made him walk up and down the hallway for tests (which was more physical effort than in the previous months combined), and refused to speak to him if he lay down afterwards. Unsurprisingly, my son’s symptoms worsened afterwards; he has not been able to leave his room since November. Versions of such experiences are widespread across the ME/CFS community.

Patients are torn between wanting to learn more about their condition, seeing more experts, getting more medical attention… and a legitimate fear of the consequences. They don’t have the energy to bang on the doors of doctors to demand more help, and often cannot afford the after-effects of doctors’ attention and ministrations. As a result, they hide at home, in their box. They are missing from medical research and care, as emphasized in the very apt title of the ME/CFS public awareness campaign “Millions missing”.

In consequence, good, comprehensive data on severe and very severe cases of ME/CFS is hard to come by. Research on ME/CFS emphasizes the experiences of mild and moderate cases. And at an individual level, patients slip from the attention of the medical system, and are branded as uncooperative for skipping recommended tests.

As a result, there is an urgent need for more research on very severe ME/CFS but with new approaches. This research needs to be well-thought-out and sensitive to the needs of the patients: get as much information as possible with no disturbance. Researchers need to get data at a distance. When physical contact is necessary, they should go to the patients in their bedrooms, but quietly, calmly, in the dark, and as non-intrusively as possible. Attention could be given to developing explicit strategies to design research around the very careful extrapolation of data, results, and knowledge from mild and medium cases to the severe and very severe ones. Innovation is needed.

The same logic applies to the medical care of individuals with very severe ME/CFS. For those patients who can tolerate it, housecalls should be easily available, not exceptions necessitating difficult negotiations. I thank my son’s family doctor for this, as well as his orthodontist who so kindly came to our home to take imprints for new retainers when one broke. For those who cannot even tolerate such contact, medical systems need to train, encourage, and facilitate means for online, textual, asynchronous consultations with generalist doctors, specialists, and psychotherapists. A video call might be too much stress and mental stimulation for a patient with brain fog and other symptoms; a text to which one can respond slowly is sometimes the best they can do.

For family, friends, and nursing carers, Linda and Greg Crowhurst propose what they call a ‘moment’ approach, for maximizing the opportunity to meet each need tenderly. Their guide sets out a philosophy of care that is very respectful of the patients, their lived experience, and cognisant that “it is difficult to be cared for without causing additional problems.”

Unlike Schrödinger’s cat, which is both dead and alive, we know that while people affected severely by ME/CFS are missing, they are very much alive. They suffer from a terrible illness and the worst quality of life. They are in need of all the attention they can get, for research and for individual care – without the noise, the prodding, the poking, and the stress. We need to observe the cat without opening the box.

Regarding severe ME, there needs to be more funding and research into ME to provide the evidence and guidelines for clinicians to work from. There needs to be somewhere within the NHS providing specialist care for patients with severe ME and an easy mechanism to access that provision.”

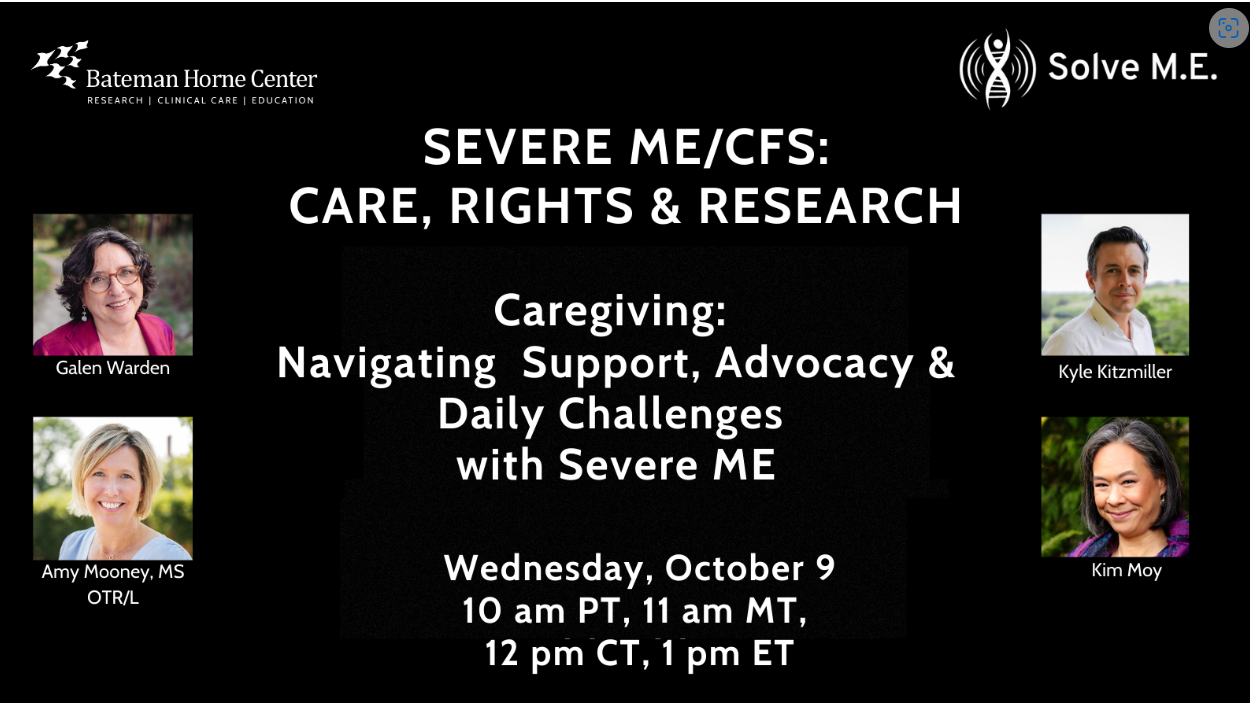

Moving Forward : The Solve M.E. / Bateman Horne Center Webinars

In a series of 4 webinars – “Severe ME/CFS: Care, Rights, and Research Webinar” – the Solve ME/CFS Initiative and the Bateman Horne Center will, over the next couple of months, probe the lives, legal situations, care and research regarding the severely ill.

The first, on October 9th, will include the mother of an adult son with severe ME, the mother of a teen daughter with severe ME, the wife of a husband with severe ME, and a husband of a woman with severe ME.

Other webinars include: Legal rights ( November 13); Medical care (December 4); Research (January 15).

You can sign up for the webinars here.

Bastards!!!

This situation here in Canada, a tragic and enraging story of an indigenous woman whose fatal medical neglect was caused by racism, has some parallels to Maeve’s story. The only difference seems to be that because racism has a much higher profile than ableism, which even then has a much higher profile than ‘invisible ableism’ (the unique variety pwME experience, often accompanied by a megadose of gaslighting), Joyce’s story has received widespread media attention and is a mainstream topic of discussion. But deadly medical neglect is deadly medical neglect, no matter the cause.

https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/montreal/joyce-echaquan-inquiry-toxicology-1.6042783

HERE HERE !!

I actually lied about the severity of my illness way back in the 90s because everytime I got online and read about how we were all crazy,(I knew I was’nt) I got scared.

i was told by one of the only two good drs. that I am severe although I’ve been upgraded to…. (I have no idea) …..after one single dose of $12 horse ivermectin

Who are these ghost writers and what is/their purpose? Who pays them to make up these online fallacies?

Better yet…Who are these evil people that are trying to keep us sick and dying?they are stopping the progression of science yet the the community claim they must use science.i don’t have time to wait for science.

This illness ruined my entire family!

After decades of searching for answers I’ve come to believe the systems are actually against us. All my self taught decades of research proved to me that there are health heros out there that have been able to reverse many of their own diseases like the lady that cured her own daughter of colitis(Elliane Gotchall). She tried telling the gastro docs but it fell on deaf ears. Just one example of many I’ve come across over the decades.

There is an oncologist, dr. Seyfried at Boston university online,all over youtube that knows how to reverse many cancers by starving the cancer yet his findings are falling on deaf ears. He has many people claiming he has cured them simply by not giving the cancer the ” food” that makes cancer grow…glucose.He sites many pioneer oncologists from decades ago that cured cancers but it’s all been buried.

There is a website called

” quackwatch ” that pounces on all these healers that use sometimes unorthodox methods of healing. These healers have to cross the border into Mexico to set up shop and heal people because the system doesn’t like their toes stepped over or on.

I used to think the system was right about quacks on “quackwatch” because my wife worked at the hospital for 35 years.

My thinking ,after decades of severe illness , neglect, abuse, gaslighting has now lead me to wonder who are the real quacks

roonie, i so agree with all of this – I thought my drs would be THRILLED to hear that I resolved my cervical dystonia (aka focal seizure) with the keto diet- well known to the medical community to treat intractable epilepsy/seizures, which I had tried out of desperation.

every time there was a holiday/ special occasion and I went off the diet for a few days bam my neck would seize up -repeatable over 2-3 years! they had zero interest and tried to say my dystonia was simply in remission and it was coincidence that i would seize up every few months when i went off the diet. if they can’t make money on it- they just don’t care. it’s pathetic and beyond infuriating. sending all my best, sara

I heard about that tragic story. Racism undoubtedly played a huge role, but what was missing in media reports was the big “S”. Yes, sexism in medical care kills thousands and thousands of women every year, and leaves even more of them permanently disabled.

Fauci made sure to classify ME/CFS was a “women’s disease” with no meaningful funding.

Let’s mention the fact that some indigenous women,

UNKNOWINGLY have been sterilized,(unable to give birth)by

“The system”

I find this very disturbing given where I thought we were at in 2024

Extremely sad and unfortunately, very true. The “Elephant in the Room” is found in most every “room” of the medical field regardless of the country, state, town, village, or metropolitan area/medical facility, clinic, specialist program and/or rehabilitation situation. What to do with “them” is the question with few (if any) answers.

What to do? Exhausted, I live one day at a time, sometimes disgusted, sometimes accepting. Even living in CA, USA and having access to “trained medical specialists”, I am not taken seriously in many instances. Having to defend my diagnosis/s, seek appropriate care/treatment, make and keep appointments, etc., ….I return to bed, exhausted and yet willing to begin tomorrow, or the next day, or the next. Yes indeed, Roonie, they can truly be as you named them. Perhaps someday, very soon, breakthrough will come and all can get back to living.

How sad for Maeve’s loved ones. To see your daughter suffering and being powerless. And then instead of good help, there is resistance or no help. I hope she is at peace now. It’s a terrible disease. Many of us suffer in our own ways. Much suffering can be prevented by simply recognizing the disease. And treat patients with respect. Why doesn’t that happen? Are those the so-called scientists who know everything so well? And do you have the best interests of the patients or people at heart? THE science is so limited it’s almost laughable

and now I’m crying … i’m glad there’s a touch more attention coming to the ME/CFS community, but the fact that this is where we are in 2024 is just a lot to sit with. thank you as always for continuing to shine a light on our community.

I can really relate to her situation. I am 70″ and 112#. Having CFS/ME after a respiratory viral infection leading to severe Guillain Barre. Misdiagnosed due my hyperflexic reflexes. Not given the appropriate treatment that would have reduced the severity and duration. On top of that I was diagnosed with lymphocytic esophagitis after a PET scan. It’s painful to even swallow saliva much less medicine and food. I am nauseous with zero appetite Then finding out my Cardiac CT Calcium score was 2758 and my apo (a) was 228 All of this puts me at exceptional risk for MACE and or Stroke. I have been attempting to drink the very high calorie Boost having 530 calories per bottle. I live alone with zero social contact. Being autistic with ADHD I have very low social skills. My specialists don’t have a clue about chronic fatigue. I am 71 years old and I try to count my blessings each and every day I am given. I don’t blame anyone for my situation and am eternally grateful for the accomplishments I have made through out my Life. The article hit home with me as I know starving to death is slow and gentle. Really nobody at the largest medical complex in the world can relate to my situation. I am sick and tired of physicians not being able to treat you as a whole person.

A lot going on Roberta! Good luck and congratulations for making it this far and being able to appreciate what it took to do that. I remember Dan Neuffer, I think it was saying, until you’re out of the illness you’ll never really understand how strong you had to be withstand it.

Thanks for the article, Cort, you keep us so well informed. I was following Maeve’s story from the UK…such a sad outcome for her and her family 🙁

I liked the Schrodinger’s cat analogy and illustration, so very apt for explaining the severely ill ME/CFS patients.

We all need to be cured from this wretched illness, don’t we?

I have been ill for over 30 years, and it’s certainly no walk in the park. Personally, what helps me is the knowledge from the bible – that soon God is going to bring an end to all of man’s suffering here on earth and bring about a permanent cure from all our sicknesses, even old age and death.

So, we will live on an earth free of sickness and living a healthy life – how our Creator intended us to live!

(Revelation 21:3-5). He says “The former things have passed away. Look! I am making all things new. Write, for these words are faithful and true”.

No man can ever bring that about, but our loving Creator can. We can be confident because we have his word on it.

Thank you , Josie.

Don’t trust the medical profession to understand this illness. Keep them away at all costs has been my experience over the past 20 years. The recent emphasis in the UK on “safeguarding” vulnerable people leaves severe sufferers and their carers open to abuse by ignorant nurses and doctors.

Thank you , Cort, for highlighting the plight of those who have been, or were, so very severely I’ll, and yet still dismissed by doctors, so even family doesn’t really believe how sick we have been. The horrible treatment of unbelief by doctors that is still going on is unbelievable at this stage. When will this end so that we are not afraid to tell a doctor we have CFS. And have had for 40 years or more. This is the true tragedy of being sick with CFS.

How nice it would be to just be able to say I have ME/CFS without feeling that pit in your stomach….

Good way to put it. Will that day truly arrive? I keep thinking long after I’m dead and gone.

I think it will take awhile but I also think it will keep getting easier and easier. (A biomarker would help a lot! :))

After seeing numerous neurologists, I was given the diagnosis of MULTIPLE SCLEROSIS. I was given medication, which helped, but my condition was rapidly deteriorating. Ultimately, I learned about the useful MS-4 protocol at vine healthcentre co m. This treatment has helped greatly with reducing my symptoms, it was even more effective than the prescription drugs I was using. My tremors mysteriously disappeared after the first month of medication, and I was able to walk better. Within 4 months on this treatment most of my symptoms has vanished. The MS-4 protocol is a total game changer for me. I’m surprised more people with MS don’t know it. This MS-4 protocol is a breakthrough

I searched for “MS-4 protocol” and cannot find anything. I also looked on the vinehealthcentre web site and don’t see anything there. Do you have more info on how to find info for this? Thanks.

Vinehealthcentre. com

I’m so glad for you, Jeanine. Sadly my brother died from MS after experimental treatments that basically killed his immune system. I wish they would have known back then, what they are discover now and helped you .

Yes, my sister in law has progressive M.S.

They told her that if she gets these “new injections”($2000/pc)

“That it will stop her M.S. from progressing”….hasn’t done a dam thing

Sure lined somebody’s pocket though$$$$$$$$$$$%%

A couple of people with ME/CFS have done well with Copaxone.

I am in NJ, in my box. I am an MSW who wrote federal grants for juveniles in our judiciary system. Disabled in 2001.

I am invisible in spite of reaching out. I am slowly starting to starve.

I hear you, Susan. I am sorry that you are in such a terrible situation.

I am only moderately ill. I can’t really imagine what you are going through.

Is there anything someone in the community could do for you to alleviate your suffering just a little bit?

Maeve is now free.

Thanks for pointing out the good point that came out of this, i.e. the Prevention of Future Deaths Report.

From own experience of becoming severe, I think one effect that contributes to severe grade is simply “mechanical” i.e. what I call the “Pacing Watershed”: Once energy/exertion tolerance drops under the minimum amount of energy/exertion required per day (the pacing watershed) and there is no help, it becomes kind of self-perpetuating simply because patients are forced to overexert for basic self-care, and regeneration of energy reserves will become very difficult.