The Canadian Consensus and International Consensus Criteria are much beloved by the chronic fatigue syndrome community and it’s easy to see why; after decades of dealing with a vague definition, people with ME/CFS could finally see themselves in a definition for the first time. Created from within the community by ME/CFS practitioners, researchers and advocates, the general consensus has been that these criteria couldn’t replace the Fukuda definition too quickly, and that doing so will solve some of the research problems this disorder faces. They have been a breath of hope for many.

Two DePaul University studies lead by Dr. Jason’s DePaul University team suggest, however, that these definitions could actually make things worse. While they do capture a more ME/CFS-like group they appear to be plucking out a subset of patients with more psychiatric disorders.

The Study (this study has not been published on PubMed yet, the abstract is provided below.)

Contrasting Case Definitions: The ME International Consensus Criteria vs. the Fukuda et al. CFS Criteria Abigail A. Brown, Leonard A. Jason, Meredyth A. Evans & Samantha Flores DePaul University

Study Abstract: This article contrasts the Myalgic Encephalomyelitis International Consensus Criteria (ME-ICC; Carruthers et al., 2011) with the Fukuda et al. (1994) CFS criteria. Findings indicated that the ME-ICC case definition criteria identified a subset of patients with more functional impairments and physical, mental and cognitive problems than the larger group of patients meeting the Fukuda et al. (1994) criteria. The sample of patients meeting ME-ICC criteria also had significantly greater rates of psychiatric comorbidity. These findings suggest that utilizing the MEICC may identify a more homogenous group of individuals with more severe symptomatology and functional impairment. Implications of the high rates of psychiatric comorbidity found in the ME-ICC sample are discussed.

This study took patients from a variety of sources including physician referrals around the Chicago area, selected 114 who met the Fukuda criteria and then assessed whether they met the ICC criteria. They then assessed each groups symptom severity and functionality using a variety of questionnaires, took their heart rate and then analysed the data to see what types of patients met the two criteria.

Better Scoring System

One thing Jason has going for him is an excellent symptom questionnaire (DePaul Symptom Questionnaire -DSQ). Brilliant in its simplicity, the DSQ is a retrospective head slapper. In past surveys a severe headache once a month counted the same as a severe headache daily; all you could mark was that you had a severe headache. Since Jason looks at both frequency and severity he can rank symptoms according to how significant they really are. ((Frequency score x 33.3) x severity score then /100)). In this survey a moderate headache occurring regularly will get a much higher score than one occurring a couple of times a month.

Results

More Functionally Disabled – check!

The ICC did a superb job of picking out more functionally disabled patients; Jason’s survey found almost 50 symptoms which were significantly worse in ICC selected patients than the Fukuda patients.

More ME/CFS-Like – check!

When I talked to Dr. Jason he noted that the creation of the Fukuda definition was a reaction to the concern that the Holmes definition was bringing in too many people with psychiatric diagnoses. The cure for that problem was simply to reduce the number of required symptoms from eight to four. That worked, Dr. Jason thought – the number of psychiatric diagnoses did drop – but where Fukuda et. al erred was in allowing any combination of the eight symptoms to qualify you for CFS.

That meant you could qualify for ME/CFS without having any of the core symptoms of this disorder; post-exertional malaise, cognitive problems and unrefreshing sleep. That almost certainly meant the Fukuda definition was allowing at least some people into studies who did not have ME/CFS.

The ICC was designed to fix that fault and it appears that it did. The group meeting the ICC criteria were particularly cognitively and exertion challenged and many cognitive scores and the post exertional malaise score were significantly higher than in the Fukuda group . This suggested that the group meeting the ICC criteria was indeed more ME/CFS-like than the group meeting the Fukuda criteria – an important accomplishment.

Not Over Representing Psychiatric Disorders…..Fail

The shocking finding was that the CCC and CCC are selecting more people with psychiatric disorders than the much maligned Fukuda definition

One of the concerns regarding the Fukuda definition was that it was so vague that people with other disorders who did not have ME/CFS were being included in studies. Ironically, Jason’s study suggests the ME-ICC may be bringing in significantly more people with psychiatric disorders than the Fukuda definition ever did, and for the opposite reason – it’s too specific.

Jason pointed to fatigue studies which indicate that the more symptoms a definition requires, the more likely it will select for people with more psychiatric disorders; in particular, somatization disorder. Like the defunct Holmes definition the ICC requires that eight symptoms be present and that may be too many.

It’s not that ME/CFS patients don’t have a lot of symptoms; they have a lot of symptoms but unless a definition focuses on a disorders ‘ordinal’ symptoms; ie that groups of symptoms that are particular to that disorder – it risks classifying other disorders as ME/CFS.

Even though the CCC and ICC did require several ordinal symptoms Jason’s study suggested the large number of symptoms required still caused them to select out people with more psychiatric disorders. Since Jason’s study focused on CFS patients its not clear that the ICC would also inadvertently bring in people with mood disorders who do not have ME/CFS but it’s at least theoretically possible.

Because people with more severe illnesses are probably more like to have mood disorders an increased rate of psychiatric disorders might be expected in this more functionally disabled group but the percentage of psychiatric disorders was so much higher in the ICC group (61%) compared to he Fukuda group (27%) that more than illness severity must have been in play. (An earlier study found increased rates of mental (and physical) illnesses in Canadian Consensus Criteria derived patients vs Fukuda Definition derived patients as well. )

This study was small and needs to be validated. The higher percentage of gradual onset patients suggests that while physician referrals were included the study included patients not typically seen in ME/CFS specialists office. They are, however, probably more reflective of the population at large.

Potentially Very Negative Consequences

If the data is even close to being correct psychologists in the UK and Europe would start finding much higher rate of psychiatric disorders in ME/CFS suggesting that in a worse scenario the ICC could inadvertently become a Trojan horse, so to speak, that helped get ME/CFS more identified with psychological disorders. What a shock that would be.

It’s also possible and, one would think probable, that the ICC would select out patients who showed more physiological abnormalities as well but given the attitudes of the research community the focus could still shift to a psychological one.

The loss of these definitions would be difficult to take given how enthusiasm they’ve generated but thankfully finding a definition that doesn’t have highlight psychiatric issues but still defines an ME/CFS group should not be that difficult. In fact it’s already been done.

Minor Tweaks Needed

If the ICC needs to be tweaked at least it’s not that far off; it’s got core characteristics of ME/CFS embedded in it; it simply needs to pare down the number of other symptoms it requires for a diagnosis. Jason found that an ME definition based on Ramsay’s criteria was pretty darn close; it picked out a more severely ill group of patients than the Fukuda definition without increased rates of psychiatric illness. That definition required sudden onset, post-exertional malaise, one neurocognitive symptom and one autonomic symptom.

A Pathway to a New Definition

You need a pathway – Dr. Jason

The jist of all this is that Dr. Jason believes that an ME/CFS definition needs to be a) relatively brief (probably around 4 symptoms) and b) derived empirically; that is, derived through statistical analysis. Not only is the subject matter too complex but an empirically derived definition would gain the trust of researchers and pharmaceutical companies. None of the at least eight definitions (Holmes, Fukuda, Oxford, Empirical, Pediatric, Hyde, London, Canadian Consensus, International Consensus, Myalgic Encephalomyelitis) created for ME/CFS have been empirically derived but Jason has produced a pathway to generate one.

He Has A Plan

It’s a four-step process.

Leonard Jason believes a definition for ME/CFS needs to be derived empirically and he has a plan to do that.

(1) define the core symptoms of the illness and operationalize them (ie find ways to get valid data on them by connecting physiological indices to self-report measures). Jason has noticed that in many data sets, as well as in many ME case definitions, post-exertional malaise, cognitive issues and unrefreshing sleep are core, fundamental symptoms and his group is working to operationalize those and other symptoms and issues associated with ME and CFS.

PEM is found in other disorders but it is a critical and core symptom of ME. Jason has validated ways to measure post-exertional malaise using a questionnaire specifically developed for ME/CFS (called the ME/CFS Fatigue Types Questionnaire.) In that study, controls did not have this symptom whereas patients did. Unrefreshing sleep is common in healthy people and it occurs in almost all patients with ME. Many ME theorists have also noted neurocognitive symptoms such as memory and concentration problems. Throw the three symptoms together and you may have the start of a definition for ME. ( Pain is a core symptom for many but not all people with ME.)

Jason noted one of his graduate students is currently trying to operationalize sudden vs gradual onset. The problem is actually quite complex one; how sudden is sudden? What if you had a series of colds that just got worse? At which point do you determine you have ME/CFS? What if you got sick, got better and then got sick again?There are many issues like this with our case definitions, and to increase reliability, we need ways to better operationalize these concepts.

(2) use the symptom questionnaire (DSQ) across many groups to check validity of the core symptoms. Jason’s already got about 500 DSQ questionnaires answered; the DSQ is being used in the CAA Biobank, the CDC multi-center physician project, the Bested Clinic in Vancouver and others and will soon be integrated into RedCap, which will make it accessible to thousands of researchers around the world. This instrument allows an investigator to reliability indicate which case definition a patient meets, and then it is possible to statistically compare and contrast the different definitions, including the Canadian ME/CFS criteria as well as the ME-ICC criteria.

(3) All current case definitions are based on consensus methods, but statistical approaches using data mining and factor analysis can be employed to identify core symptom domains.

(4) Come up with research and clinical definitions. The research case definition is the tightest and needs to occur first. Then the clinical case definition with looser criteria to include more individuals who really have the illness but might have just missed making the research criteria. The goal of the research criteria is to includes as broad swath of ME/CFS patients as possible without including other types of patients. Given that focus, the research criteria will probably always be a bit too constrictive; ie it will miss some patients but so long as it gets a representative sample it will be fine. The clinical criteria will pick up the rest of the patients.

Conclusions

The CCC and ICC moved the field forward by identifying and requiring that core symptoms be present and by identifying more functionally disabled groups. Two DePaul University studies lead by Dr. Jason’s team, however, suggest that requiring eight symptoms be present may cause the criteria to select out a patient subset with more psychiatric disorders. Their studies suggest that a shorter definition that includes the core symptoms may be more appropriate. Dr. Jason has worked out a pathway to produce a statistically derived definition.

If the DePaul studies are correct this is a painful moment for a community that placed so much hope on these definitions. These definitions were never going to be last word, though, for ME/CFS. By highlighting the need for an ME/CFS definition to focus on the hallmark symptoms of this disorder, the CCC and ICC have played an enormous role. Nothing in this study suggests they are not excellent clinical definitions; the question is whether they’re suitable for research purposes.

Given the continuing search for biomarkers and more and more evidence of subsets, we may and hopefully will be talking more and more about changes in ME/CFS definitions over the next couple of years. Hopefully we will.

No more questionnaires. Why are they making this so difficult? Each “symptom” must have proven evidence behind it, ie tilt table test. Assessment based on “vague” symptoms and complaints has got to end. It doesn’t help anyone.

Hopefully it will. I think we’re still going to have questionnaires but if Jason can prove that they’re producing statistically valid results – and are producing a good ME/CFS group – then that will set the stage for studies that find more abnormalities which will allow for a biologically based definition.

I’ll be interested to see the objective tests for post-Exertional malaise, and for fatigue. Questionnaires are not ideal, but for some symptoms may be the best option available.

Why is it necessary to capture every singel symptom? How does proven ANS, Immune dysfunction, etc get translated into “fatigue”. It seems for a lot of people who have the above plus abnormal MRI, PET, VO2 Max, nutritional deficiencies, etc this is a pushed aside for ABSOLUTELY ASININE meaningless questionnaires where the conclusion is “chronic fatigue”.

The current system is completely laughable. The CDC and MDs should be ashamed of the current state of affairs in this diagnosis. The question that needs to be raised is not how many people are missed but how many people who don’t have “CFS” are brought into this cesspool.

I for one refuse to fill out any more questionnaires. Just because statistics are involved that doesn’t translate into it being helpful and it certainly doesn’t translate into it being scientific.

I think it depends whether the questionnaire is for clinical practice or research.

For clinical practice – well, not everyone has the money or access to expensive tests and the knowledgable practitioners to order and/or perform them.

From my experience, I would say don’t see anyone who doesn’t know what they are doing. If you have to educate the “professional” things will most likely end badly.

Questionnaires are the domain of psychologists, psychiatrists and other shysters. They reveal what they want them to reveal which is an excuse for CBT or expensive sugar pills, er anti-depressants. It’s a wonderful business development tool.

“None of the at least eight definitions (Holmes, Fukuda, Oxford, Empirical, Pediatric, Hyde, London, Canadian Consensus, International Consensus, Myalgic Encephalomyelitis) created for ME/CFS have been empirically derived but Jason has produced a pathway to generate one.”

Now why am I surprised at that? So many psychiatrists and psychologists have used poor statistical techniques to come up with definitions of “normal function” and “recovered” when applied to ME/CFS in order to justify their weak results. Yet in one area where the thorough and correct use of statistics would be invaluable (deciding on a core definition), they choose to rely upon their own medical experience.

If anything it should be the other way around. It is easier to decide what levels of activity and energy are acceptable as being within normal range than it is to decide which amongst a wide variety of symptoms are key to defining the illness. And, of course, we need that if we are to home in on a clear-cut biomarker.

🙂

May I refer everyone to Graham’s analysis of the PACE trial here – http://www.cortjohnson.org/blog/2013/03/01/not-keeping-pace-analysis-suggests-cbtget-study-findings-in-chronic-fatigue-syndrome-mecfs-biased-and-overstated/

I think Lenny Jason is bang on when he says statistical routes are the way to a validated case definition. At the time I thought it was a little odd that he wasn’t part of the ICC definition group, but maybe that was a deliberate choice by him. Certainly he was looking at statistical options before the ICC came along.

I did wonder if taking a consensus approach, the ICC did, means that all the participants push for their preferred symptom clusters to be included so that the final results is over specified. That’s a very good way to begin case definition, but there’s a role for numbers too, to show which of these symptoms cluster together in patient groups. The CDC multi-site study is trying to gather such data, but interestingly the initial findings, reported by Elizabeth Unger at the FDA workshop, found that clear subgroups did not emerge, so they are expanding to biological markers, cognitive studies and exercise testing. Which sounds like a good idea. If they can get patient self-report and biological and objective mental/physical test data on the same patients, maybe they will have what they need to a meaningful case definition. Also, the latter will keep flood guy happy :), I just think we need questionnaires and objective info.

Thanks Simon,

I was surprised that Jason was not part of those definitions as well I think he’s been committed to deriving a statistically coherent definition for quite a some time

In talking to him I don’t think he was surprised how the study turned out. The Fukuda definition was created because the Holmes definition had so many symptoms. Maybe the ICC creators thought by requiring PEM and cognitive problems they could filter out some of the problems and I imagine they did filter out some, but they still ended up with a definition that snatched up alot of people with psychiatric disorders within the ME/CFS community.

Interesting. And meant to say, thanks for yet another great article

Sorry, floydguy, autocorrect mangled your name.

A psychiatrist called Kendall did some great work on how to validate case definitions. He made himself very unpopular by arguing that consensus case definitions failed to define meaningfully different psych illnesses, and they needed to gather data and look for ‘natural boundaries’ between real, different illnesses. He based his work on principles used by microbiologists to classify bacteria before DNA sequencing came along:

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12505793

Think you might enjoy, Graham 🙂

Hi Cort,

In the abstract, I see mention of ME ICC but not ME/CFS CCC. Why are they both included in this discussion? They are not the same with some different authors, correct?

Best,

Val

The ME International Consensus Criteria (ME-ICC) is the accurate term actually. The authors called the ME ICC instead using ME/CFS as they did with the Canadian Consensus Criteria.

Hi Cort,

Very interesting article, thank you.

I think Valerie was asking about the ICC and the CCC, and not about the use of the terms “ME” and “ME/CFS”.

Do you know if Lenny Jason’s results also apply to the CCC?

That is what I was asking, Rob. Thank you for clarifying.

Very interesting post. Scary too.

My Finnish doctor has made up his own diagnostic criteria, which consist of five(?) things and you have to fulfill 3-4. I can’t remember for sure what they are, as I haven’t been diagnosed using them, but he includes fever. For some reason Finnish CFS/ME patients seem to have fever about half of the time, while it’s much rarer elsewhere. Hyde(?) even claimed that fever is virtually never seen in this illness, only subnormal temperatures (that seems very strange to me, as e.g. I have chronic fever and I’m pretty much a “textbook case” otherwise, both symptom-wise and test abnormality wise – I know many others who are the same).

There is also either Ehlers-Danlos syndrome (he sees a lot of EDS patients) or positive response to LDN (EDS patients don’t seem to respond to LDN as well as other CFS/ME patients).

I don’t agree with all of his criteria, though. LDN helps autoimmune diseases and many other illnesses (including psychiatric illnesses) as well, and doesn’t help all CFS/ME patients. I’m a big advocate for it, but I don’t think it should be diagnostic.

(That’s three; I think the remaining two are PEM and sleep problems, but I’m not sure.)

Thanks, Cort for studying these definitions so well. I am certain that there are patients who have psychiatric diagnosis in their illness experience, just as there are in other diseases. It is obvious that M.E.has needed a proper definition since the CFS name was given to us. How many need understanding of M.E.? It is not just the patients in this community,but everyone. I think Dr. Jasons’ work is excellent, and never mind doing surveys for his studies. The last conference showed how proper information is greatly needed, and the definitons will come together, hopefully, very soon. Mary Silvey, RN (a Medical Professional with and for M.E.)

Thanks Mary, yes, a certain percentage of psychiatric diagnoses is normal particularly for people with a chronic illness. The Fukuda criteria group had, I think, about 24% with mood disorder – the ICC has over 60% – an enormous leap. Of course this is a small study and a bigger study might have lower figures…

Can we get back to biomarkers and some basic pathogens that are agreed upon by virtually all CFS experts?

Extremely low NK cells for starters and high viral titers to EBV, CMV, and HHV6 and other viruses.

What happened to sore throat and swollen glands as part of the CDC definition?

Why is anyone discussing a tilt table test for CFS? I have hyperadrenergic POTS, but most people with CFS do NOT have dysautonomia.

And let’s not muddy the waters with LDN or other immune modulators. Some people with CFS respond and some don’t, it’s in no way indicative of CFS.

The psychiatric community is huge and powerful. Beware, and be careful of providing them with opportunities to invade.

I put this responsibility on the shoulders of the doctors I like the most, and pay the most. I expect them to be fighting this movement with as much vigilance as they’re supporting their own CFS research.

Cort, what can we do as patients? NOT that we need to do more than we’re already doing, simply by surviving, but I’m hoping patients can come up with a partial solution to this kind of thing.

Seriously, this is getting old!

So a disease of the nervous system doesn’t need to have evidence of such? Yes, this is getting old.

I notice you didn’t mention the one Jason did a year or two ago that said ME ought to be defined by the biological abnormalities. He laid out his own proposal for how to define the disease. He separated it into two, one with symptoms that have biological abnormalities and one with symptoms without biological abnormalities. Can’t remember name of it or I would put a link here.

I also agree that consensus definition does not have the same credibility. Hoping CDC’s will provide that. Good to have more discussion now so CDC can see how to avoid making the same mistakes.

I agree that it will be very hard to separate people as to sudden or gradual onset. I had the virus that came and went throughout the year. But, with a lifestyle change, that stopped. I gained energy again, was working full time, fully functional. Then, gradually over the following three years, the hormone problems and cognitive problems gradually increased, along with fatigue. But over those three years, it was not clear that something was wrong. The gradual increase of these things I first associated with growing older, working too hard and not getting enough sleep. I occasionally thought that maybe something was wrong. But it was not very clear. I had unconsciously made changes to accommodate my symptoms so I didn’t realize how bad I was getting.

In one night, when the pain started, I then realized something was wrong.

So, was I sudden, then recovered, gradual decline and then sudden again? I never know how to answer the question of whether I was gradual or sudden.

The only way to evaluate a tool is to put it into action then tweak it until it functions as you want it to function. This is inspiring analogy and valid points. Research that bears fruit is that which defines the study participants appropriately. Without that, it is wasted money and effort. We have seen so much of that, it is time to change, and it is refreshing to see someone really evaluate the criteria. Look what happened with the FM criteria, and those who challenged it still did not stop its implementation.

This is the reference for the study whose abstract is given above:

——-

Brown, A. A., Jason, L. A., Evans, M. A., & Flores, S. (2013). Contrasting case definitions: The ME International Consensus Criteria vs. the Fukuda et al. CFS Criteria. North American Journal of Psychology, 15(1), 103-120.

——-

I dislike a rush to use terms like somatisation disorder.

I want to highlight something.

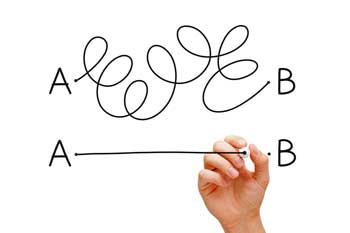

Imagine there are two sets of criteria, Criteria A and Criteria B.

Criteria A require 5 symptoms (say)

Criteria B require 11 symptoms (say), the first 5 and 6 more.

Say the rate of psychiatric disorders for Criteria A is 25% and Criteria B is 60%.

One can’t conclude from this that by using Criteria A, one will exclude many of those patients with psychiatric disorders in Criteria B. By using Criteria A alone, one won’t exclude a single patient that satisfies criteria B.

If one thinks of it in set terms, {Those satisfying Criteria B} ⊂ {Those satisfying Criteria A}. It’s like the figure at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Subset with the letters reversed.

What has happened going from 5 to 11 symptoms, is one has excluded lots of people who don’t have psychiatric problems, but one hasn’t brought in any new patients.

I am glad to see talk of both research and clinical criteria. I think the Canadian clinical criteria are better as research criteria rather than clinical criteria – some people could have an ME/CFS-type illness but not satisfy them.

Here’s an example of what can be done, from:

———–

Jason, L.A., Evans, M., Porter, N., Brown, M., Brown, A., Hunnell, J., Anderson, V., Lerch, A., De Meirleir, K., & Friedberg, F. (2010). The development of a revised Canadian Myalgic Encephalomyelitis-Chronic Fatigue Syndrome case definition. American Journal of Biochemistry and Biotechnology 6 (2): 120-135, 2010 ISSN 1553-3468. doi:10.3844/ajbbsp.2010.120.135

Retrieved from http://www.scipub.org/fulltext/ajbb/ajbb62120-135.pdf

———–

“Meeting research versus clinical criteria:

Table 1 provides all the symptoms as specified in the Revised Canadian ME/CFS case definition. Some meet full criteria whereas others who are very symptomatic do not meet full criteria. We argue as we did with the Pediatric case definition (Jason et al., 2006) that those that meet full criteria are more homogenous and might be best used for research purposes and we now classify these individuals as meeting the ***Research ME/CFS criteria***.

Still, others might have the illness but not meet one of the required criteria. We classified such individual as meeting ***Clinical ME/CFS criteria***. These individuals needed to have six or more months of fatigue and needed to report symptoms in five out of the six ME/CFS symptom categories (one of which has to be post exertional malaise, as it is critical to this case definition). In addition, for autonomic, neuroendocrine and immune manifestations, adults must have at least one symptom in any of these three categories, as opposed to one symptom from two of the three categories.

We also have a category called ***Atypical ME/CFS***, which is defined as six or more months of fatigue, but having two to four ME/CFS symptoms.

There is also a category called ***ME/CFS-Like***, which involves exhibiting all criteria categories but for a duration of fewer than 6 months.

Further, a person could be classified as having ***ME/CFS in remission*** if the person had previously been diagnosed with CFS by a physician but was not currently meeting the Research ME/CFS Criteria, Clinical ME/CFS criteria, or Atypical ME/CFS criteria and must have 0 or 1 classic ME/CFS symptoms.”

The original link for that no longer works. The paper is now free here: http://www.thescipub.com/abstract/10.3844/ajbbsp.2010.120.135

Arrgh!

What a tangled web!

Where to start?

Clearly from my previous blogs I’m not a fan of putting people into little diagnostic boxes that then exclude them from those in different boxes. The problem is that in the absence of specific biomarkers we’re trying to define a phenotype based on symptoms with little knowledge of the underlying cause while the trend in other fields is to group illnesses on the basis of the underlying pathology and not on the basis of symptoms.

I’m actually quite relieved that the ICC picks out a higher proportion with psychiatric disorders. I expected the opposite. What I find understandable but counter-productive is to deny that this disorder might have a ‘psychiatric’ element. ME was originally defined as a neurological disorder and whether its Alzheimer’s; Huntington’s; stiff person syndrome or any of the various forms of ecephalitis – they are all associated with high levels of ‘psychiatric’ symptoms whether it be depression, anxiety or even psychosis. Why assume that a neurological disease would impact on fatigue, movement, pain, cognition etc but spare the areas of the brain dealing with mood, emotion etc.

The implication appears to be that the ICC picks up more serious cases but also, because of the larger number of symptoms required, also picks up higher numbers of those with somatisation disorder. I’ve heard the argument before that the higher the number of symptoms the more likely you are dealing with a somatoform disorder. I’ve never however seen any scientific evidence to support this heuristic nor to support a ‘true’ somatisation disorder affecting more than a minute proportion of the population. On the other hand another heuristic states that the higher the number of symptoms the more likely you’re dealing with a mitochondrial disorder. So does multiple symptoms equal a somatisation disorder based on someone’s opinion or an undiagnosed mitochondrial disorder? A prior ‘diagnosis’ of somatisation is essentially meaningless.

I’m probably going to contradict myself – its a melon twister!

But this notion of a ‘pure’ ME/CFS cohort troubles me when we can’t even agree if psychiatric ‘co-morbidities’ are a key part of the disorder, a downstream effect or should exclude those with any ‘psychiatric’ symptoms from research cohorts.

The finding that the ICC selects a cohort that is both more seriously functionally impaired and more likely to have psychiatric symptoms might be expected as higher morbidity must impact on ‘mood’. On the other hand (to me) it suggests a shared pathology.

Excluding this possibility from future research doesn’t strike me as progress.

I guess one question is which definition is presenting the true face of ME/CFS?

If it is true that adding symptoms artificially increases the percentage of the rate of people with ME/CFS mood disorders that’s the same problem as if a definition required dizziness and thus focused on people with ME/CFS who had orthostatic intolerance.

How do you determine the true face of ME/CFS without deciding in advance what you want to find? The problem is exacerbated by the fact that people visiting ME/CFS physicians are clearly different from those not seeing them.

It does seem quite slippery.

I agree with Marco – what a tangled web – but hopefully resolved/tweaked soon. Just wondering what a definition of “psychiatric” illness is for starters, and personally the various symptoms/stages of ME vary in time and duration anyway. I do think the Canadians are the closest.

Good point….the fact that the illness changes over time is coming up more and more. It’s another variable to have to deal with…

I do not really see the problem if the patients picked out with the ICC and Canadian definition, have a lot of patients with depression, as long as these patients have the core-symtoms of ME, such as for example post-exertional-malaise/exhaustion and neurocognitive problems.

The state of the immune-system has an influence on mood, so an expected result of an neuroimmune disorder is to have depression. Excluding the depressed patients from the cohort, would pick-out a sub-group of ME patients, and probably leave out the majority of clear ME cases.

I would not find it convincing to create a definition where one leave out the people with co-morbid depression. As long as the core symptoms are the same, I can not find good arguments for not classify them as having ME. It is quite common for patients with ME to have to use antidepressants. I think there are both science and clinical experience that support that co-morbid depression is common in ME. Also, I think some people exerience that immunomodulators (probiotics, kutapressin, LDN) influence mood at a very small time scales (depressive symptoms and irritability may lift after a couple of hours of intake) which is indicating that the immune system is driving the depressive symptoms.

Of course, it is always possible for researcher to check if there are any differences in the subjects having comorbid depression or not, in order to assure that the groups are not different.

As the ICC and Canadian definitions pick out people that have more serious problems with post-exertional-exhaustion and neurocognitive problems, and more disability, then I really no not understand the conclusion that it would be a very big problem that these subjects also have more co-morbid depression. I would rather see it as a consequence of having a more severe neuroimmune disease.

A well known practitioner told me that many patients with ME have changes of personality, so my picture of the whole is that personality change and depression are two things that are common but rarely discussed due to the infected situation with militant psychiatrists claiming that it is a psychiatric condition with no right of existence as a separate condition.

The rate of psychiatric diagnoses was not low in Fukuda (about 25%) and yes, you would expect it to increase with increasing disability, but the rate was so high with the ICC group (60%) that I think you’re crossing into dangerous ground. We would nave to look at other really debilitated states to see what their rates are. If CFS is at 50% and other groups are at 30% then I think that might push the conversation in the psych direction.

The question for me is – can you have your cake and eat it too? I haven’t read the paper but I believe the paper on the ME definition based on Ramsay’s work delineated a group of more functionally disabled patients without such a significant increase in psychiatric diagnoses. That would be the best of both worlds.

I agree with the personality change idea; I’m definitely more irritable and I guess hypersensitive – I have the arousal thing going on. I’m not sure how far that goes; I can tell its true and I’m sure others can as well but I don’t if it pushes me into meeting the criteria for another disorder. Of course, it does depend on how which practitioner is diagnosing you.

Another question -raised but unanswered by this paper is if its possible for people without ME/CFS who have a psychiatric disorder could meet the PEM and other criteria. Jason, if given enough funding (:)) will be able to sort all this out because his questionnaire assesses symptoms really well; you have to have a high PEM rating to meeting the criteria for ME/CFS. (Of course, some people with the disorder may not have that….but you have to draw lines somewhere. )

I would not say a 60% prevalence of co-morbid depression in ME is alarming, as long as the patients have ME per see. I see no point in revising criteria, if this if this ‘high’ prevalence of depression is the only ‘problem’. Actually 60% is about the number I would expect. 25% seems very low, and I think it would be interesting to understand why it is so low.

I think depression is the expected outcome in a condition with ‘neuroinflammation’ and increased levels of cytokines and oxidative stress.

Depression and fatigue are very common symptoms, and therefore very unspecific.

It is always possible, and recommendable, for researchers to stratify data on for example type of onset, flu-like symtoms or not, depressive symtoms, severity, time having the disease, etc. If several biomedical studies, in different areas (neurologic, immunologic, etc), show that there are clear sub-groups, then things would be different.

If the differences are strong evidence of different pathophysiology and/or etiology, then one should consider to split into two conditions. If there are clear differences, but not big enough to say there are of different etiology and/or pathofysiology, then researchers should always present data by sub-group.

I’m with you on this one Eric.

Here’s the quote from Danzer included in part I of my neuroinflammatory blog :

Dantzer et al (2009) reports on recommendations from a multidisciplinary conference held in 2007 to consider how best to identify and treat medically ill patients with a range of conditions in which inflammation played a key role in the symptomology.

“The most harmful and costly health problems in the Western World are originating from a few diseases that include coronary heart disease, cancer, obesity, type II diabetes, physical disability and neurodegenerative disorders associated with ageing.

In addition to the specific symptoms that are characteristic of each of these conditions, most patients experience non-specific symptoms that are similar in all these conditions and include depressed mood, altered cognition, fatigue, and sleep disorders.”

Just because some from a psychological or psychiatric background interpret these symptoms as evidence of an absence of physical illness shouldn’t back us into a corner of denying that they may be an integral (and important) part of the disease.

Even a mechanistic (as opposed to neuroinflammatory) deficit like reduced cerebral blood flow would be expected to impact on ‘mood’.

I remain a bit sceptic that there it will be an easy task to come up with better criteria than the ICC and the Canadian one, but of course it very interesting discussing if one should go towards more or less obligatory symptoms, and try to understand what such changes result in.

For myself I have questioned the use of such long lists of symptoms, but that only one, and any one, has to be present, in the ICC and Canadian criteria. To me it seems that one decreases specificity, but not necessarily increasing sensitivity to the same degree. Longer lists of symptoms are excellent in descriptions as it will give a good idea of what it is all about, but if one uses long lists of symptoms and one only have to have one, then it will be more likely that any given person will fit to the criteria in some way, and the likely hood increases that some people are selected that an ME specialist would not classify as ME.

One symptom I miss in the list of ICC is ‘new intolerance to alcohol’, which I think is a common feature in ME and probably not present in so many other conditions.

I think it is very important to have the whole patient history and context. There are typical ways that patients get sick. Some symptoms have a tendency to be strong in the beginning, as for example night sweats, but then wane. This whole picture I think is important.

The “original” description of Ramsay has some virtues that I think are important to not lose in the process. Some call it a criteria, but actually it was a description of what he saw as typical features of the patients. I think more people should read the original text of Melvin Ramsay, it is excellent. In the chapter of the endemic form of ME, he writes for example “Muscle fatigability whereby, even after a minor degree of physical effort, three, four or even five days, or longer, elapse before full muscle power is restored and constitutes the sheet anchor of diagnosis”. At one place he describes the patients as having a general sense of ‘feeling awful’ which I think would be synonymous to ‘severe malaise’.

I am unsure if one today consider ME patients having lower muscle power. As I understand it we do have basically normal static muscle power, if tested in a machine, so either the Ramsay patients were different or that he based the results on subjective testing, and clearly patients with aching nerves, increased lactic-acid, central fatigue and/or aching muscles will avoid effort.

I think that it is important with both criteria and descriptions, and that experienced clinicians make the diagnosis. But of course the problems arise that clinicians have a tendency to have their own ideas of “what is typically ME”, so therefore the need for criteria, especially in research. But it is also important to let the clinicians experiences “feed-back” on the criteria, as criteria are no more than criteria, i.e. an attempt to properly select a cohort of patients.

The use of statistical methods in order to dissect the different criteria and to understand the cohorts better is very interesting and one can learn a lot, but would it be possible to use the statistics in such a way that one can feel that one properly select one type of patients? If one simply have to have a sufficient score on one sum of many things, then I do not think so, but if one have to have sufficient scores on several variables, then it may so, but I think the way is very difficult and that the path to a criteria is full of pitfalls, and highly dependable on the ingeniousness of the statistician. There are an infinite amount of ways to mathematically express a criteria, i.e. shall it be the sum of three or five variables, or the maximum value of eight, or shall one make a sum of the variables in square, or the product of the square root? Shall one variable be the product of frequency and severity, or the sum of frequency and severity, or the sum of the frequency raised to the 1.5th power multiplied with the severity to the 1.8th power? Shall one use multidimensional analysis where each frequency and severity is a vector in space, and one use multi-dimensional statistical methods, in order to find the sub-spaces that are the most sensitive and specific ones? But what it the original space was not optimally selected? What if it had been a lot better to select a different co-ordinate system, a spheric, a cylindrical, etc?

Boy are we on the same page with intolerance to alcohol but surprisingly, at least to me, that symptom came in low in both groups. The sensitivity to alcohol scores were pretty low (26/34).

One of the symptoms that surprised me was frequency of urination. That was one of the higher symptoms tested.

Orthostatic intolerance symptoms were low to moderate. Neurological symptoms were high…

Only that symptoms that differed significantly were listed; we don’t have all of them..

If I recall correctly one of Jason’s papers (perhaps this one) compared the frequency of symptoms across I think it was three case definitions including the Canadian Consensus and alcohol intolerance came out around 30% regardless of the criteria.

So definitely an interesting finding and worth explaining – but only for a sub-set.

And please don’t talk to me about frequency of urination. That alone probably prevented any ‘deconditioning’ on my part.

PS – Orthostatic intolerance and frequent urination are apparently the most common early symptoms of autonomic neuropathy.

I needed a laugh – thanks 🙂 I don’t get that unless I drink water; if I drink much water it just flows through..

I think the somewhat demeaning designation of CFS and the relatively weak filtering process that several CFS criteria apply have probably removed at least some level of patient scrutiny for CCC/ICC (I certainly welcomed them with open arms on the first and even subsequent viewings).

In my opinion, which isn’t exactly professional, I think specific research criteria is overrated since it hasn’t been decided how many distinct illnesses or illness triggers might exist in the ME/CFS spectrum. It may be more efficient to target specific common symptoms in ME/CFS patients and develop research based on them.

I should also point out for those who have a CFS classification, but do not have dysautomnia, I developed autonomic symptoms some time after my initial ME/CFS diagnosis as my illness became more severe.

The Lloyd – Vollmer-Conna group is look at that question right now; they’re trying to determine if the ANS is more perturbed in people who come down with ME/CFS or does it show up later? That study is going to take a couple of years, though.

Yay to Tom Kindlon. Of course you are right about criteria A including all those meeting Criteria B. The definitions A to B are not mutually exclusive. This really pints out how tricky it is to get the correct definition.

And Marco, always so right on. Clinical depression or mood disorder is common among chronic illnesses of all types. For everyone who says these patients need to be excluded from a definition of ME/CFS, let them live with it for a decade or several, then get back to us.

Thirdly, I do like Lenny Jason so much. He is kind and patient. What a champion he’s been for us! However, Dr. Jason is a psychologist, and psychologists are all about statistical analyses. I can’t see this disease being ready for that. Perhaps his questionnaire suffices. I don’t know. It just seems we need more measurable symptoms in a research setting before we can apply the statistics.

Just a word about aging. I haven’t a clue how 60ish people feel physically. I’m stuck forever at age 49. Somehow aging and all the changes that come with it will need to be excluded if we’re ever to nail the right population for ME/CFS. Frankly, I don’t know if I’ve declined cognitively and physically because of aging or CFS.

Finally, to those who have trouble with sudden and gradual onset, we seem to be a large group. I exhibited all of those core CFS symptoms within a week; however, it took 16 mos. to take me out of the workplace. My daughter keeled over, spent 3 weeks in bed and has never been the same.

To Cort, as always, thanks for your hard work.

The fact that the ICC shows a greater percentage of Psychiatric diagnoses compared to the Fuduka can probably be accounted for the following reason.

1- ICC criteria diagnosed patients are more severely affected and because of their limited functionality might express more feelings of depression.

2- ICC patients in general probably have been ill for a longer period of time and have developed tremendous feelings of frustrations and perhaps anxiety.

3- ICC diagnosed patients probably experience more cognitive/neurological problems which can be scary and limit their cerebral functioning.

The question is, are these Psychiatric diagnosis a RESULT of the main diagnosis or is it just a co-morbid diagnosis?

Good point. Time is another element. They did not assess duration of illness; that would have been very interesting.

Demographically, the two groups did not differ significantly with regards to age (which indirectly suggests duration was not an issue – but only indirectly), gender, work status, education level, whether the illness appeared to be caused by a virus what they believed the cause of the illness.

The two groups differed significantly on type of onset (more acute in ICC p<.05, and the number of psychiatric disorders (p<. 001>

Thanks for the article, Cort.

I haven’t yet read any of Jason’s research that relates to this article.

I highly value Lenny Jason’s research.

But this article raises so many more questions than it answers.

It almost makes me ask if Jason is focusing too narrowly on physical disability in order to make a diagnosis of ME.

For some other researchers, I would ask if they were aware that ME has a serious and incapacitating neurological/cognitive component.

But Lenny Jason must surely must be aware of this.

So I wonder why it is a surprise, or considered undesirable, that, the ICC (which requires both PENE, and neurological symptoms; whereas Fukuda does not require either PEM or cognitive symptoms) creates a cohort with very much a higher rate of co-morbid psychiatric symptoms.

The cognitive issues have always been my biggest complaint.

When the symptoms (fatigue/malaise/exhaustion) are on my brain, my brain goes into shut-down.

The difference between physical and mental incapacity cannot be over-stated, in my opinion.

When the symptoms are on my body, but not on my brain, at least I can engage in life, to some degree.

Whereas, when the symptoms are on my brain, this cuts out so much of my life, including: my memories, my sense of self, my confidence, my ability to engage with people and socialise, my ability to be intellectually and emotionally independent; my ability to thrive emotionally; my ability to read and write; etc etc etc.

The way cognitive disability affects a person cannot be described in a few words. It is highly destructive.

If I purely had physical symptoms, and no cognitive symptoms, then it would be so much more easier to adapt, both mentally and physically.

Mental symptoms wipe out a person’s life.

I understand the differences, because my cognitive symptoms wax and wane, and I have had episodes of relative cognitive clarity, and episodes of cognitive shut-down.

So I wonder if Lenny Jason is fully taking into account the devastation that increased cognitive symptoms contribute.

I worry that the neurological nature of ME might be thrown out, in the attempt to avoid psychiatric co-morbidity.

ARE WE ASKING THE RIGHT QUESTIONS?

Cort, you’ve written a very thought-provoking piece. But I can’t help thinking we need to flesh this topic out, and also ask some tougher questions. I’m having a rare “OK” day, so will make hay while the sun shines and perhaps contribute a related perspective.

1) ISSUE #1: IF WE TREAT THE OSTENSIBLE PSYCH COMORBIDITY, WILL IT RETURN US TO FUNCTION?

For me as a patient, all I ultimately care about is: “What do we have to treat, to restore patients to a modicum of functionality?” And the answer to this question has EVERYTHING to do with whether psychiatric comorbidity (if present) is primary, i.e. integral to M.E. as a disease; or secondary, i.e. a natural sequela to profound disability.

Why is this important? Because if we perseverate on the possibility of profoundly ill patients being depressed, for example, and if we’re sloppy in our assumptions, we can put ourselves in exactly the position that the UK is, where CBT and GET are positioned (despite a lot of arm-waving by the psychs) as the be-all and end-all for ME and CFS patients. I.E. The Psych perspective is being positioned as a fix-all for ME and CFS. To whit, the endemic refusal of biomedical testing, to better understand the biomedical underpinnings of ME and CFS – much less biomed treatment.

I submit that any time psych comorbidity is raised, we have to be meticulous about identifying whether, if we treat that psych comorbidity, that will address the core pathology of ME or CFS, and return the ME or CFS patient a significant measure of functionality. Or whether said psych treatment will just help patients cope better. (And I don’t for a moment believe that treating “false illness beliefs” or graded exercise are safe, much less helpful in ME, even for coping). Consider the number of Rituxan or Ampligen patients who have been able to return to work after treatment – versus those in the PACE trial, which has been consistent in its INABILITY to return patients to work. And this is a big deal, considering – as Dr Unger stated last week about the patients her multi-site research, “What was consistent, was that 75 percent were not working.”

How many of us, for example, have been prescribed antidepressants, only to find them less than useless in affecting our level of disability, much less our abilty to do self-care, or return to work?

And how many of us have been lucky enough to get some biomedical treatment which returned us, dramatically, to a measure of our former lives? I’ve had a small number of blessed but TOTAL remissions on IVIg – unfortunately formulations that are no longer available to me. But I’ve experienced it – from a few days to a week after treatment, spontaneously waking up refreshed in the morning, BOUNCING out of bed, clear of mind, with to-do lists bubbling up with joy; being able to go for walks with the family; able to make meals; tolerating standing up; being cognitively clear enough to dream up all kinds of fun things to do. And being “myself” again, for as long as 3 months after these treatments. With no PEM nor angina. It was like the movie “Awakenings”. Pure joy. Did this affect my mental state? Darn right it did. I felt like myself again.

ISSUE #2: WE NEED TO DIG DEEPER TO UNDERSTAND “HOW” THEY ARE DEFINING PSYCHIATRIC COMORBIDITY

I would also argue that any time someone says that psych issues are comorbid, we need to go to their assumptions – i.e. the tools they are using – to see if those are in fact appropriate to our disease or spectrum of diseases. Specifically, we need to know if these tools can differentiate between a depressed patient, and someone who is naturally responding as a result of profound disability.

If you take a peek at Valentijn’s posts at this link: http://forums.phoenixrising.me/index.php?threads/depression-questionnaires-in-me-cfs.21578/#post-329074 , he provides examples of common depression inventories such as the Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory, the SF36, and the Zung Depression Scale, where a so-called diagnosis of depression could in fact be merely an assertion of significant biomedical disability.

For example, how many ME patients would respond affirmatively to the following – not because they’re depressed, but because they have lost a massive chunk of their quality of life, and have had to contract their life to prevent relapses? Here are just a few of the questions that would peg ME patients as “depressed”:

– “I have a lot of plans”

– “I still enjoy the things I used to do”;

– “I expect my health to get worse”

How many of us expect our health to get worse – not because we’re pessimists, but because we are realistically extrapolating from our past health trajectory, and factoring our slim hopes for imminent treatment? Given how widely used depression inventories are, that have lousy specificity and sensitivity, we must be vigilant about such assumptions about “psychiatric comorbidity”, when applied to a serious multisystem and chronic illness such as ME.

3) MULTISYSTEM SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS CONFLATED WITH SOMATIZATION PAR EXCELLENCE?

Next, while many psych instruments make the assumption that more physical symptoms = somatization (and indeed this skewed assumption is becoming entrenched in psych practice – witness the bastardization of the DSM), anyone with a complex multisystem disease knows differently. But as we saw this year, simply having multiple symptoms, and being concerned about them, will increasingly be taken by the DSM folks as signs of somatization. It’s all in the definition, even if it isn’t supported by science.

Bottom line, I would offer that we need to dig deeper, whenever we see people conflating ME with psychiatric comorbidity, with the ultimate questions always foremost in our minds: “Just how do they arrive at this conclusion of psych comorbidity?”, and “If we treat the so-called psych comorbidity, will this restore the patient to function?”. Proof of principle, in reverse.

4) WHICH ASPECTS OF DEPRESSION – IF PRESENT – ARE FEATURED?

Another consideration is that we need to tease out specifically which aspects of depression – if that is the issue – are coming up as positive in an ME or CFS population. I found it fascinating that at last week’s FDA meeting, Dr Unger made a point of saying that it’s NOT the Role Emotional or mental health that are coming up in her multi-site study of “ME/CFS” patients. Now, even Dr Unger is saying that not all instruments have been validated in CFS, and even she is breaking some paradigms, by saying that Mental Health and Role Emotional are PRESERVED in CFS. Very, very interesting stuff. As she said (from the preliminary transcript on PR):

“In the SF36 … you can see that the bars are all very low except for two of them. And … those two relatively high scores are on … mental health and (role) emotional indicating those areas of function are preserved in CFS and that again is pretty consistent across all of the clinics.” (WOW, just wow… what a change of tune. I thought it was STUNNING to hear the CDC, of all entities, say this)

And more from Dr Unger: “This is also giving us a hint that measures themselves may be limited in their ability to distinguish robust phenotypes and/or robust subgroups, and that’s why we’re proposing to expand this study to some other measures. And it could very well be that other biologic correlates will be needed in order to better define subgroups. The other study — other factor is that the data from these kinds of studies will allow us to evaluate how well these questionnaires work. For example, the MFI general fatigue scale in this population really from a specialty clinics did — was limited by its already reaching the maximum in 40 percent of the patients.”

A CARDIAC EXAMPLE – THE WOMEN’S ISCHEMIA SYNDROME EVALUATION (WISE study)

There’s another example of assumptions-gone-wild in the Women’s Ischemia Syndrome Evaluation, a massive NIH initiative looking at women with chest pain, but often clear-as-a-bell coronary arteries. These women nevertheless present with cardiac ischemia; and these women are at TEN TIMES the risk of cardiovascular events (death, myocardial infarction, stroke, etc) from those without chest pain. As it turns out, this population is heavily represented by multiple comorbidities, with chronic pain conditions such as FM, “CFS”, IBS, interstitial cystitis, migraine, and Raynaud’s – exactly the constellation of comorbidities associated with “ME/CFS”. In other words, ME and CFS are likely well represented in this WISE population of women who are dying prematurely from heart disease. And indeed, that’s what the work of Dr Newton and her team at the U of Dundee would suggest (http://www.meresearch.org.uk/research/studies/2012/endofunction.html ).

This makes one finding from the WISE study stand out: the WISE researchers found that, “Anhedonia Predicts Major Adverse Cardiac Events and Mortality in Patients 1 Year After Acute Coronary Syndrome (ACS)” (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3058237 )

“Depression is a consistent predictor of recurrent events and mortality in ACS patients, but it has 2 core diagnostic criteria with distinct biological correlates—depressed mood and anhedonia… anhedonia and MDE (Major Depressive Episode) were significant predictors of combined Major Adverse Cardiac Events (MACE)/ All Cause Mortality (ACM), BUT DEPRESSED MOOD WAS NOT.”

“… Anhedonia identifies risk for MACE/ACM beyond that of established medical prognostic indicators. Biological correlates of anhedonia may add to the understanding of the link between depression and heart disease.”

IMO, the most pressing “biological correlate” of anhedonia that I can think of in this population, heavily represented by “chronic pain conditions” such as ME and CFS, is Post-Exertional Neuro-Immune Exhaustion – mislabeled as “anhedonia”. In other words, the WISE researchers need to start cross-pollenating with “ME/CFS” research, and start measuring for NK cell dysfunction, RNase-L abnormalities, cytokine profiles, etc.

This is an assumption about depression, among the massive team of WISE researchers that so far has gone unchecked.

THE KEY MESSAGE: WE NEED TO CHALLENGE GRATUITIOUS ASSUMPTIONS ABOUT COMORBIDITY

So will there be psych comorbidities in any chronic illness, particularly one with neurocognitive involvement? Absolutely? But let’s be aware that entrenched forces have a tendency to overstate that linkage in ME and CFS. Specifically, let’s come back to this subgroup of CBT/GET practitioners whose “business is rehabilitation” (Wessely’s comment from this BMJ Group Podcast http://www.bmj.com/podcast/2010/03/05/chronic-fatigue-syndrome – see 11 minute, 15 seconds for his quote). It needs saying that this is an all-out war for market share and credibility, and for the psychiatric paradigm of “CFS”, this tenuous hold on credibility requires that they keep the largest and most expansive definition of the disease(s). We feed into this grab for market share, if we don’t ask tough enough questions, whenever psych comorbidity is conflated with ME or even CFS. Just how are they arriving at this linkage?

I do find it deeply worrisome that so many people are comfortable making the implied leap that just because there is a hint that significantly disabled patients despair at times, that the treatment must equal psychiatric. It is a massive leap of logic that is not justified by science. True, there are other neurocognitive aspects of this disease that might blur into psych domains. But we need to be precise when discussing this.

All I’m sayin’ is that we need to probe a little deeper, and DEMAND treatment that “fixes” us – not window dressing. And this starts with dissection of the assumptions that drive our historically limited treatment options.

Now to throw a spanner in the works. In my earlier life, I used to research corporate health outcomes, and saw – in insurance payouts – the impact of psychosocial factors on health cost and health outcomes. For example, in workplaces where employees had poor control over how they did their work, and high demands, combined with high effort and low reward (“high stress workplaces”), we saw an increase in colorectal cancer by a factor of 6; back pain by a factor of 3; injuries and infections by a factor of 2-3, and so on. So I DO believe that psychosocial factors can drive and influence health outcomes – I’ve seen it in the corporate health numbers. BUT never in a million years, however, would I support that any disease precipitated, influenced, or exacerbated by psychosocial factors – aka epigenetic changes – have its treatment LIMITED to psych therapy. That’s just silly.

Just think how ludicrous it would be to tell a colorectal cancer patient that they are going to receive ONLY GET and CBT, AND no more biomedical testing nor treatment because psychosocial factors may have precipitated or worsened their disease. But somehow society has allowed this runaway train, especially in the UK, to run amok, and to make this grandiose and unsupported leap of logic, where it pertains to ME and CFS. This, we have to stop. And a first step might be in demanding precision, whenever psych issues are conflated with ME/CFS. “Just how are you defining this?” “What are your underlying assumptions”?

We need to dig deeper.

Bravo! And granular data!

Could someone bring Lenny Jason’s attention to these comments? Especially to Parvofighter’s comment… Cort?

I’m searching for the “like” button.

Thank you! And BTW, I’ve been asked if it’s OK to repost my above note. By all means, yes. My only request is that you please repost the entire contents of my above post, with credit to this page link for Cort’s site, and credit to Parvo.

I’m looking for the ‘Like’ button too.

As a twenty five year sufferer of M.E. who has gone on to develop frank epilepsy and a b-cell leukemia usually suffered by elderly men (i am female and diagnosed with this leuemia in my early fifties) I find it difficult to see my illness/es to have been caused by a psychiatric disorder. And in spite of my illnesses I still remain positive and have suffered no depression. Anyone with a neurological disease process or any disease process which pulls the rug from under them could be expected to a have comorbid so-called mood disorder. I’m probably slightly off topic here but my brain is done in from too much reading. Thanks Cort for this interesting topic.

Wow Parvo!

You are having a good day.

(I’d add a smiley if I knew how)

I would say that ME/CFS patients are often mislabeled as having depression because to the common person and many doctors they appear depressed – they have so little energy that they do very few if any of the life activities they did before becoming ill, they often show little emotion or affect (due to a lack of enough energy to even smile or laugh), they have sleep problems and digestive problems, and especially in the severely ill may not feel life is worth living. All of these are cardinal symptoms of depression and so I agree with others that it is no surprise that 60% of very ill patients would also meet the definition of depression. That said I think exercise intolerance and other biomarkers will help separate out those who have ME/CFS from those who have depression due to another cause.

I say other cause because I think psychiatric diagnosis are often blind to any possible physical cause for psychological and emotional symptoms. I mean how many people diagnosed with depression have an undiagnosed thyroid or other hormonal disorder? A nutritional disorder or gluten intolerance/celiac disease? Mood changes due to mold exposure or chemical sensitivities? Can someone have depression due to just emotional/interpersonal issues? I think so, but I do not think it is the first place doctors should be looking.

I would be interested Cort if you could find out more about what Jason thinks about somatization disorder as I think it too is way over used and what he thinks of the DSM-5 revisions to it.

James, you’ve put into words what I’ve long believed. Thank you!

Do you mind if your note is reposted, with credit?

Cort, I have been encouraged to ask why you include the ME/CFS CCC with the ME ICC in the intro to the article here? They are not the same definitions with slightly different authors, and the ME/CFS CCC does not seem to be part of this study per se according to the abstract above – only the ME ICC definition.

Thanks for the heads-up on this upcoming issue, but with the FDA meeting just finished, the CFSAC coming up and the May 12th Awareness day, we want to be clear on what we are dealing with before we get feathers too ruffled. Very precious energy goes to all of these things – at least for myself.

A lot of our lives have been enhanced by the ME/CFS CCC particularly and I hope it turns out to still be helpful for researchers and clinicians alike. (Can you tell I have a Canadian bias although it is actually an international definition?)

Please let us know when the study is available and where to gain more understanding. Thanks.

I understand the questions and the upset. I’ve thought that all we needed to do was turn the CCC or ICC into a research definition and we were set to go. Even if that’s not true both have changed the landscape for ME/CFS (they were the first really to use ME/CFS for one thing) and they highlighted the mistakes the Fukuda definition made and they highlighted the need to identify and require core symptoms. Those are huge accomplishments.

As I noted earlier as well, there was always going to be a need for an empirically derived definition; no one outside the field – particularly industry – is likely to be willing to invest millions of dollar to produce a drug, say, using a definition that was derived from a consensus. They’ll want statistically derived definitions; as the field matures they were going to happen anyway.

I included the CCC because an earlier study by Dr. Jason contrasting the Fukuda Definition, an ME definition and the CCC found much the same thing; the CCC patients had a higher incidence of ‘mental problems’ than the Fukuda or the ME definition while the ME definition picked out people with more physical and cognitive problems. I have not read that study but Dr. Jason alluded to it when I talked to him and it seems have the same general results.

The ME/CFS case definition criteria (CCC) identified a subset of patients with more functional impairments and physical, mental, and cognitive problems than the subset not meeting these criteria. The ME subset had more functional impairments, and more severe physical and cognitive symptoms than the subset not meeting ME criteria.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22158691

Of particular worry to me is the assumption of the psyches or anyone else for that matter that “depression” may be classed as co-morbid psychiatric, recalling at worst when barely able to function physically or mentally it might appear so to any observer. In fact apart from being periodically fed up with Docs this was never the case – too tired to be depressed in the common sense of the word – bodiy “systems” depressed to the point of barely existing.

Hey Enid, check out what Lenny Jason just sent out; I think you’re going to like it. I think he was responding to you comments. I think this is just an amazing finding and it really demonstrates how powerful the tools he’s using are.

For those that want my take on the issue of whether those with CFS can be differentiated from those with Major Depressive Disorder, I had worked on that issue an number of years ago with a graduate student, and our article that was published indicated that it was possible with the right symptoms and scoring to differentiate these conditions with 100% accuracy.

The article has this reference and the abstract is below:

Hawk, C., Jason, L.A., & Torres-Harding, S. (2006). Differential diagnosis of chronic fatigue syndrome and major depressive disorder. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 13, 244-251. PMID: 17078775

The goal of the present study was to identify variables that successfully differentiated patients with chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS), major depressive disorder (MDD) and controls. Fifteen participants were recruited for each of these three groups, and discriminant function analyses were conducted.

Using symptom occurrence and severity data from the Fukuda and colleagues (1994) definitional criteria, the best predictors were post-exertional malaise, unrefreshing sleep, and impaired memory and concentration. Symptom occurrence variables only correctly classified 84.4% of cases, whereas when using symptom severity ratings, 91.1% were correctly classified. Finally, when using percent of time fatigue was reported, post-exertional malaise severity, unrefreshing sleep severity, confusion / disorientation severity, shortness of breath severity, and self-reproach to predict group membership, 100% were classified correctly.

I get a little bit sad of this eternal discussion. It is useless. I think that symptomatic subjective criteria is very difficult for science to accept. For ME/CFS there is no unique symptom. Only ‘PEM’ is. I think we need objective markers. We can use HRV (autonomic dysfunction) , NK-cel funtion (immune dysfunction) and measure blood titers of EBV, CMV and HHV6/7 (infection). This is a simple strategy to start and is not very expensive.

Agreed. It would be really interesting to see Jason examine the results of those “markers”. The strange thing is how readily symptoms like anxiety, depression, aches, etc are accepted. I think in order to flip the focus ANS dysfunction, NK Cell Function and infections must be focused on. Is it perfect? Absolutely not but at least the focus is on proven abnormalities not mind body issues that may never be accepted or effectively treated.

Until you’ve suffered from clinical depression and ME/CFS separated by nearly fifteen years (never simultaneously) you can’t possibly know how laughable, how ignorant, how ludicrous it is to think think Ramsay’s ME, the CCC, or the ICC could ever be applied to one who has depression.

If there are more individuals like me, we need to start speaking up.

I’n not quite sure I’m following you Polly but I feel it might be an important point.

Could you please elaborate?

Marco, I will try.

First, let me say that I was diagnosed by a psychiatrist with clinical depression, and by a specialist with ME/CFS, so there can be no argument about accurate diagnoses. To repeat, I never had these illnesses simultaneously.

There are stark differences in symptoms between the two illnesses, and, quite frankly, in my experience they don’t have a single symptom in common. Therefore, I am confounded how the ME, CCC, or ICC definitions could identify/include individuals with clinical depression.

Also, these definitions, in my opinion, couldn’t even identify a comorbid clinical depression. As I said, in my experience, clinical depression has its own set of symptoms none of which include any symptom of ME/CFS.

I hope this helps to clarify.

I am with you Polly.

I had a bout of clinical depression 9 years before getting ME/CFS. They were nothing alike. Depression involved a lot of rumination and self-reproach, as Leonard Jason describes it. I could do activities, but just didn’t want to do them. Physically I felt fine and as long as I got my mind off of the rumination I could do cognitively challenging work. ME/CFS, for me, feels like having a permanent severe concussion while being poisoned. I want to do activities but can’t. The only rumination I have involves wishing I hadn’t spent so much time in moldy locations or in polluted foreign cities. There is basically no overlap.

I agree with a lot of the posters here that it seems strange for Leonard Jason (who is great) to be concerned that a definition includes a lot of people with co-morbid psychiatric conditions. Most severe ME/CFS patients I know have depression or anxiety as a symptom of their neuro-inflammatory condition and I would be shocked if it were otherwise.

Julia,

Thanks so much for posting. I believe you are right on with your explanation. I’m sure this has helped in everyone’s understanding.

Hi Cort, is this the research that you have written about?:

http://www.questia.com/library/1G1-322563471/contrasting-case-definitions-the-me-international

Yes

Lenny Jason sent an email stating that he’s following the discussion and that he’s “benefited from the excellent discussion and consideration of important issues.” and he added some clarifications. It also appears that an updated study soon in a appear in the IACFS/ME Fatigue journal may have not found increased mental issues in patients that meet the CCC criteria.

This just makes me glad that we have someone like Lenny who is addressing these issues in an organized manner.

For those that want my take on the issue of whether those with CFS can be differentiated from those with Major Depressive Disorder, I had worked on that issue an number of years ago with a graduate student, and our article that was published indicated that it was possible with the right symptoms and scoring to differentiate these conditions with 100% accuracy.

The article has this reference and the abstract is below:

Hawk, C., Jason, L.A., & Torres-Harding, S. (2006). Differential diagnosis of chronic fatigue syndrome and major depressive disorder. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 13, 244-251. PMID: 17078775

The goal of the present study was to identify variables that successfully differentiated patients with chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS), major depressive disorder (MDD) and controls. Fifteen participants were recruited for each of these three groups, and discriminant function analyses were conducted. Using symptom occurrence and severity data from the Fukuda and colleagues (1994) definitional criteria, the best predictors were post-exertional malaise, unrefreshing sleep, and impaired memory and concentration. Symptom occurrence variables only correctly classified 84.4% of cases, whereas when using symptom severity ratings, 91.1% were correctly classified. Finally, when using percent of time fatigue was reported, post-exertional malaise severity, unrefreshing sleep severity, confusion / disorientation severity, shortness of breath severity, and self-reproach to predict group membership, 100% were classified correctly.

I also have a paper that will appear very soon in the new Fatigue journal, and the reference and abstract are below, and this might also be of interest to your readers:

Jason, L.A., Brown, A., Evans, M., & Sunnquist, M. (in press). Contrasting Chronic Fatigue Syndrome versus Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. Fatigue: Biomedicine, Health & Behavior

Abstract