SENSORY GATING PART V – VALIDATION?

A – Sensory Gating Deficits and Neuroinflammation in ME/CFS – A Testable Hypothesis

- Part I – Sensory Gating – Set out a hypothesis that, if tested, ME/CFS patients (in particular those patients that would describe themselves as the ‘Wired and Tired’ type) might be found to have a sensory gating deficit which might explain various symptoms not often discussed in ME/CFS literature. These include various sensitivities to light, sound, touch, smell, etc., that might be considered to be a kind of sensory defensiveness and which can lead to sensory overload. Part I also identified a range of conditions (including those involving pain, mood disorders, neuropsychiatric and neurodegenerative disorders) that are already known to result in sensory gating deficits and, while usually considered to be discrete and separate disorders, they all appeared to share common underlying pathophysiologies including immune perturbations, oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction (all of which have been identified in ME/CFS). One small study (described in a dissertation) had examined sensory gating in adolescent ME/CFS patients and significant results were found after controlling for other variables.

-

Part II – Glutamate – Identified a neuroinflammatory ‘vicious cycle’ that could underlie most if not all of the conditions associated with a sensory gating deficit (with diabetes/metabolic syndrome also showing an association). Glutamate (or more precisely an imbalance between glutamate and GABA) is increasingly implicated in these conditions and in ‘mental fatigue’ and various encephalopathies, which may result in a self-perpetuating cycle of glutamate excitoxicity, oxidative stress, and mitochondrial dysfunction. It was suggested that such a vicious cycle might be the underpinning pathology in ME/CFS.

- Part III- Stiff Person Syndrome– Described stiff person syndrome, a rare and disabling condition in which a glutamate/GABA imbalance results in both mood/neuropsychiatric symptoms and significant physical disability including painful muscle spasms that can be triggered by various sensory or other stressors. Part III also discussed how stiff person syndrome is believed to be of autoimmune origin but may also have a viral trigger – a mechanism which may also underlie some alleged psychiatric disorders and may play a role in ME/CFS.

- Part IV- Neuroinflammation – Attempted to show how such a neuroinflammatory process could explain not only the cardinal and minor symptoms of ME/CFS (and those ‘atypical’ symptoms that started this inquiry) but also those consistent biological findings that point to a multi-systemic illness but for which, at present, no unifying process has been confirmed. It also suggested that the neuroinflammatory state underlying ME/CFS is not benign – resulting only in ‘dysperception’ of sensory inputs – but that over time it may lead to progressive nerve damage resulting in various peripheral and autonomic neuropathies, and may also hasten the development of a range of inflammatory/degenerative conditions usually associated with aging.

I believe what I have set out is plausible, but I accept that the whole model depends initially on confirmation that ME/CFS patients do indeed share a sensory gating deficit with those other conditions, and that this may be a measurable artifact of a shared neuroinflammatory state. I also accept that one study described in a student dissertation is flimsy evidence on which to build a case, and consequently stated that a sensory gating deficit in ME/CFS remains a ‘testable hypothesis’.

Sensory Gating in ME/CFS – ‘Made in Japan’

“The findings in the present study were consonant with the hypothesis that patients with CCFS have brain dysfunction”

When I first started to look into what might be causing the various ‘sensory processing’ abnormalities in ME/CFS (well over a year ago) I was happy that I had practiced ‘due diligence’ – using terms commonly used in sensory gating paradigms including ‘sensory gating’, PPI, ERP, P50, Startle, CFS, ME, etc., to search the (mostly Anglophone) published literature – in attempting to identify any existing research that might support or refute the notion of a sensory gating deficit in ME/CFS

What I hadn’t counted on was that (a) a key publication might not include any of these exact terms in its title and (b) would originate from outside the western hemisphere. It was only by luck that I came across the published research that will be the subject of most of the following discussion.

Event-related potentials in Japanese childhood chronic fatigue syndrome. Akemi Tomoda, Kei Miyuno, Nobuki Murayama, Takaka Joudoi, Tomohiko Igasaki. Journal of Pediatric Neurology, January 2007. http://iospress.metapress.com/content/w14pg23t125337q8/

Not just any ME/CFS Study

This large and comprehensive study included tests for sensory gating, autonomic functioning and cognition.

This is an unusual study for several key reasons:

- First, and most important, it is a large study (by ME/CFS standards) with 414 patients and 190 age-matched healthy control subjects;

- The study focused on childhood chronic fatigue syndrome (CCFS). Patients were 9 to 18 years of age, and all met the CDC Fukuda criteria with the numbers of males and females roughly equal;

- Rather than focusing on one single measure and testing one hypothesis, the researchers simultaneously measured cognitive function/information processing; autonomic function, and frontal lobe function, all of which have been reported to be impaired in ME/CFS;

- Rather than simply carry out ‘group comparisons’ between all CCFS patients and all controls, they were able to measure individual responses. On the basis of these, as will be discussed further below, they were able to objectively identify two distinct subgroups within this CCFS cohort.

The same researchers (Tomoda, et al., 1995, 2000) have previously noted decreased regional cerebral blood flow and a “remarkable elevation of the choline/creatine ratio” in CCFS patients. The latter finding has also been associated with brain tumours, with autism (Sokol et al., 2008) and in inflammatory processes such as ischemia (Hesselink, undated) – a condition involving glutamate toxicity (Ischemic cascade – Wikipedia).

Tomoda, et al., however concluded that these findings did not necessarily indicate a high level cognitive processing deficit. The current study was intended to investigate such a deficit.

TESTS

P300 ERP – Oddball paradigm

This does sound a little ‘oddball. P300 ERP is a measure of cognitive function, specifically attention ‘allocation’ (the orienting of attention), and information processing (efficiency/reactivity) to stimuli.

In this test a small number of ‘target’ stimuli are presented at random among a larger number of ‘non-target’ stimuli. The subjects are asked to respond (usually via a button press) when a target is detected. In this case visual stimuli were used with a circle as the target and a cross as the non-target.

Each individual’s responses to these stimuli were measured as ERPs (event related potentials, which are brain electrical signals detected by electrodes) which you may recall from Part I is one of the measures used to investigate sensory gating. P300 refers to the time in milliseconds from the stimulus onset to the peak brain response.

The task requires both maintaining attention to the task of detecting target stimuli and discriminating between target and non-target. Both amplitude (the peak signal) and latency (time taken for peak response) were measured following each target or non target stimulus.

Compared to the gating measures discussed in Part I which involved the early ‘gating out’ of irrelevant stimuli, this is a later, higher level measure of ‘gating in’ where attention is oriented towards novel (comparatively rare) target stimuli.

Autonomic Function – ECG ‘RR’ Intervals

Electrocardiograph (ECG) measurement of heart RR (beat to beat) intervals (Wikipedia – Heart Rate Variability) is intended to measure the ratio between the sympathetic and parasympathetic sides of the nervous system, with the low frequency component (LFC) reflecting the sympathetic and the high frequency component (HFC) the parasympathetic system.

While often considered to be complementary excitatory (sympathetic) and inhibitory (parasympathetic) facets of the autonomic nervous system, with a few exceptions it is now considered that these two systems work interactively:

“the sympathetic nervous system is a ‘quick response mobilizing system’ and the parasympathetic is a ‘more slowly activated dampening system’.

“For an analogy to an automobile, one may think of the sympathetic division as the accelerator and the parasympathetic division as the brake. The sympathetic division typically functions in actions requiring quick responses. The parasympathetic division functions with actions that do not require immediate reaction. The sympathetic system is often considered the ‘fight or flight’ system, while the parasympathetic system is often considered the ‘rest and digest’ or ‘feed and breed’ system.” (Wikipedia – Autonomic Nervous System)

The ratio between the LFC and HFC components therefore represents the balance between the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous system.

KANA Pick Out Test

This test is widely used in Japan to test frontal lobe function in conditions such as Parkinson’s Disease and dementia to assess both short term working memory and executive function/multi-tasking (impairments in both of which have frequently been reported in ME/CFS).

Kana are Japanese written symbols which equate to vowels. The test requires subjects to read a short passage (in this case a fairy tale) for comprehension while simultaneously being required to indicate which vowel symbols (Kana) appear in the text. Subjects are scored on both vowels identified and overall story comprehension.

The test can also be interpreted as simultaneously measuring a continuous task (ongoing comprehension of the story) and a discrete task (identifying vowels).

Compared to a single task, the simultaneous dual task requires far greater mental resources, and some have proposed that poor performance on this dual task may reflect a cognitive processing ‘bottleneck’ (Tachibana et al., 2012).

“Diminished performance during dual tasks, compared to performance of separate single tasks, is attributed to the allocation of limited resources to attend to and perform competing task requirements.”

You may also recall Rönnbäck and Hansson’s description of mental fatigue resulting from continuous mental effort without a break, which was discussed in Part II : .

“a decreased ability to intake and process information over time. Mental exhaustion becomes pronounced when cognitive tasks have to be performed for longer time periods with no breaks (cognitive loading).”

Results

Cognitive Function – P300 ERP

As mentioned above, in measuring cognitive function, these researchers did not just test group differences for significance, but tested each individual patient against the mean values for healthy controls on the two measures of P300 – amplitude (peak response) and latency (time taken to respond). An abnormal response (i.e., a significant difference between a patient’s score and controls) was defined as being two standard deviations outside the mean value of the corresponding data from the controls.

The investigators approach made it easier for subsets, if they were present, to show up….and they did.

To put this in perspective, if they had been measuring intelligence (IQ), to be considered ‘abnormal’ a patient’s score would have to be either below 70 (borderline deficient) or above 130 (very superior intelligence) compared to the mean of 100 and a standard deviation of 15.

This approach turned out to be key to identifying three patient subgroups which may not have been recognized if they had just compared the CCFS group as a whole against normal controls. Particularly, as will be seen, on some measures the subgroups trended in opposite directions.

The results for all the measures have been tabulated below.

|

Patient subgroups compared to healthy controls |

||||

| Type I (n=40) | Type II (n=49) | Type III (n=325) | All Patient Groups | |

| ERP Amplitude (Target) | Lower than controls | Higher than controls | Below threshold of significance | No difference |

| ERP Amplitude (Non-Target) | Lower than controls | Abnormally increased | Below threshold of significance | Increased amplitude |

| ERP Latency to target | Abnormally prolonged | Reduced | Reduced | Reduced latency |

| Low/High Autonomic ratio | Very low parasympathetic | Low parasympathetic | Very low parasympathetic | Low parasympathetic |

| Kana pick out test | 25% | 75% | 50% | Lower than controls |

All CCFS Patients

As can be seen, for the CCFS patients as a whole, on the ERP measure there was no difference between them and healthy controls on the response amplitude (strength of response) to the target stimulus, while the overall CCFS response to the non-target stimulus was higher than that of healthy controls.

In terms of latency (time taken for peak response to stimuli), CCFS patients responded quicker as a group than healthy controls.

However, these group results largely mask some very significant findings.

Poles Apart? The Hyper/Hypo-active Subsets….

One group (termed Type I and comprising 40 patients) had an abnormally prolonged latency (a slower time to respond) compared to controls, and the strength of response (amplitude) to both target and non-target stimuli was lower than controls.

In contrast another sub-group (termed Type II and comprising 49 patients) had an abnormally increased response (amplitude) to the non-target stimulus compared to controls, while their response to the target stimulus was also increased and the latency (time to respond) to the target stimulus was reduced.

In summary, Type II showed pretty much the opposite picture to Type I.

The remaining 325 patients whose responses were not found to be statistically abnormal compared to controls were termed Type III; however, as discussed below, their status on other measures was far from ‘normal’.

Part III of the Neuroinflammatory Series made the observation that ME/CFS may comprise subgroups in a similar fashion to attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder, which includes the inattentive, hyperactive and mixed or combined subgroups.

It’s interesting to note that (without having a theoretical rationale outside of hypothesized maladaptive patterns of thinking and behaviour) some biopsychosocial researchers have suggested two broad types of behaviour in ME/CFS – an avoidance/inactivity pattern and a hyperactive pattern leading to ‘boom and bust’ (PACE Manual for Therapists V2, 2004).

Autonomic Function. Sympathetic/Parasympathetic Ratio

As with other findings CCFS patients, as a group, showed evidence of autonomic dysfunction. (Freeman and Komaroff, 1997; Newton et al., 2007; Beaumont et al., 2012). CCFS patients had low parasympathetic function, or in other words, sympathetic dominance which reflected a sustained response from the ‘fight and flight’ side of the autonomic nervous system.

It’s interesting that both Type I and Type III subgroups had ‘very low’ parasympathetic function while type II was just ‘low’.

Frontal Lobe Function

From our own experience and numerous anecdotal reports (not to mention the cognitive deficits stated in the various case definitions), cognitive deficits are common in ME/CFS, yet the results of studies have been mixed with some researchers concluding that patients’ reports of the severity of cognitive deficits are not matched by objective findings outside of slowed processing speed (Scheffers et al., 1992; Wearden, Appleby, 1996) while others have suggested that any cognitive problems may be due to co-morbid depression. Recent studies, however, have successfully shown that cognitive deficits in ME/CFS may appear by some measures to be subtle, but are ‘real’ whether or not ‘co-morbid’ mood disorders are present (Constant et al., 2011; Cockshell, Mathias, 2013).

Again, the finding of three subgroups in this cohort with, in some cases, results which trended in opposite directions may have contributed to previous negative or apparently inconsequential findings.

When scores were summed for mistakes made in either story comprehension or vowel identification, healthy controls made no errors and consequently scored 100%.

Startling Cognitive Deficits Found

The performance deficits found in the CCFS patients were startling with the best performing patients scoring only 75% and the worst 25%. Even a 25% reduction in important cognitive abilities such as short-term memory and executive function should be a major cause for concern, but a loss of 75% of these functions must be devastating, particularly in children (whose cognitive abilities are still developing).

Executive Functioning – higher level processes that control and manage “planning, working memory, attention, problem solving, verbal reasoning, inhibition, mental flexibility, task switching and initiation and monitoring of actions” (Executive Functions, Wikipedia)

To put these findings into perspective, the Kana Pick Out Test was originally used to test for cognitive impairments in dementia, and while frontal lobe dysfunction in isolation is considered to represent ‘mild’ dementia or ‘mild cognitive impairment’, it affects many everyday activities and is defined by the Mayo Clinic as follows :

“Mild cognitive impairment (MCI) is an intermediate stage between the expected cognitive decline of normal aging and the more serious decline of dementia. It can involve problems with memory, language, thinking and judgement that are greater than normal age-related changes.”

Bear in mind that these were children between 9 and 18 years of age whose cognitive abilities should be developing and not showing deficits in excess of those usually found in the elderly!

Discussion

“their higher nervous system has deteriorated as demented subjects were previously reported to have longer P300 latencies”

I don’t intend here to go much beyond what the researchers have concluded.

Type I –Slower and Less Efficient Cognitive Functioning

Reduced ERP amplitude and prolonged latency (as seen in the Type I subgroup) has been reported in fibromyalgia patients (Alanoğlu et al., 2005), in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder (O’Donnell et al., 2004), major depression (Işıntaş et al., 2012), adult ADHD (Szuromi et al., 2011) and multiple sclerosis (Honig et al., 1992) and these findings are also associated with aging and Alzheimer’s Disease. This suggests conditions such as schizophrenia and bipolar disorder may also involve neurodegeneration (Mathalon et al., 1999) as appears to be the case with ADHD (Szuromi et al.).

Similar deficits in cognitive function as measured by P300 ERP have also been found in the (currently unaffected) children of Alzheimer’s patients suggesting a familial predisposition to neurodegeneration (Ally et al., 2006).

Generally a reduction in amplitude and prolonged latency suggests slower and less efficient cognitive function as would be expected in aging and dementia.

Type II – The ‘Wired and Tired’ Group

“their nervous system has an abnormal, hypersensitive reaction: a nervous state”.

The sensory gating tests suggested the nervous system of the ‘wired and tired’ group was in a ‘nervous state’

Increased amplitude of P300 ERP (as found with the Type II patients) has been previously associated with phobia, panic disorder, generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) and ‘introversion’ while reduced latency ( also seen with type II) may suggest higher cognitive function (compared to prolonged latencies) but is also associated with obsessive compulsive disorder (Sur, Sinha, 2009). (P300 ERP findings for visual stimuli in autism spectrum disorder (ASD) are mixed, perhaps reflecting the ‘spectrum’ nature of the disorder, but early ERP responses (signals with latency less than 300 ms) are also exaggerated for ‘non-target’ stimuli (Baruth et al., 2010).

It’s notable that P300 ERP amplitude normally increases with novelty and salience (or meaningfulness) of the stimuli, and that in PTSD increased amplitude is only found when the stimulus is relevant to the original trauma. In these Type II patients, the fact that the ERP amplitude was abnormally increased for non-target stimuli suggests a general state of ‘hyper-arousal’ where even irrelevant and common stimuli evoke a strong (and rapid) response. Clearly (in terms of this measure) these patients appear to fit the ‘Wired and Tired’ ME/CFS type.

TYPE III – Trending ‘Wired and Tired’

Type III patients represent by far the largest group. While findings for this group were not statistically abnormal and the paper provides few details, it is possible to make some inferences:

If their responses were essentially neutral (not long or short latency or not high or low amplitude) then the overall mean response would be skewed in the direction one of the ‘extreme’ groups (Type I or II where one of the responses was significantly abnormal where in numerical terms both groups are almost identical). This may be the case with ERP amplitude in response to non-target stimulus, as group II had a statistically abnormally increased amplitude and the amplitude for all patients was also increased but not significantly.

However, as regards latency, all patients showed reduced latency but group I was the only significantly abnormal group and demonstrated prolonged latency.

This strongly suggests that, on the ERP measures, the Type III group trended in the direction of the Type II ‘Wired and Tired’ type.

Autonomic dysfunction – Sympathetic Dominance…. (again)

A reduction in the ratio of the parasympathetic (rest and digest) to sympathetic (fight and flight) autonomic components (along with reduced heart rate variability and vagal tone) has been associated with ASD (Ming et al., 2005), schizophrenia (Fujibayashi et al., 2009), bipolar disorder (Latalova et al., 2010), major depression (Carney et al., 2005), PTSD (Sherin, Nemeroff, 2011), fibromyalgia, IBS (Manabe et al., 2009) and Huntington’s Disease (Ahmad, Roos, 2010).

Intriguingly, (as with the P300 ERP findings in Alzheimer’s) unaffected first degree relatives of those with schizophrenia also had similar autonomic dysfunction, perhaps reflecting a shared genetic predisposition for both conditions (Bär et al., 2010).

Of note also is that autonomic symptoms may precede cognitive deficits in Huntington’s Disease, and autonomic dysfunction in major depression may be worsened by some antidepressants (Koschke et al., 2009).

Sympathetic dominance is also associated with metabolic syndrome (which as seen in Part II has been linked with ME/CFS) and indeed may predict the onset of metabolic disorders (Lict et al., 2013) :

“Increased sympathetic activity predicts an increase in metabolic abnormalities over time. These findings suggest that a dysregulation of the autonomic nervous system is an important predictor of cardiovascular diseases and diabetes through dysregulating lipid metabolism and blood pressure over time.”

As previously discussed on Health Rising, this pattern of autonomic dysfunction (as well as being associated with the above conditions) may predict increased mortality in a range of conditions and is a risk factor for cardiovascular disease.

Frontal Lobe Function

The results of the KANA Pick Out Test speak for themselves. Even the best performing group (Type II) had a 25% deficit compared to healthy controls while the Type I group with a 75% deficit might well merit a description in terms of IQ of at least ‘borderline deficient’.

Needless to say, deficits in functions associated with the frontal lobe such as executive function are found in most, if not all, of the ‘behavioural’ (ASD, ADHD, OCD, PTSD), ‘mood’ (Schizophrenia, MDD, Bipolar disorder, anxiety disorders) and neurodegenerative diseases (Alzheimer’s, Huntington’s, etc.) but also in ‘pain’ disorders such as fibromyalgia and IBS. Unfortunately direct comparisons are not available as the Kana Pick Out Test appears to be used in few of these conditions outside of the neurodegenerative ones.

What did the researchers conclude?

These researchersdidn’t mince words in their interpretation of their findings. They suggest that these results may reflect a high order brain function abnormality:

“…abnormal P300 patterns and frontal dysfunctions might be associated with a high-order brain function abnormality in patients with CCFS”

and

“The findings in the present study were consonant with the hypothesis that patients with CCFS have brain dysfunction”

Type I – They infer that in these patients:

“their higher nervous system has deteriorated as demented subjects were previously reported to have longer P300 latencies”

While these findings are correlational (that is, they can’t prove that CCFS is responsible) they do suggest that these young patients may have a learning dysfunction and also highlight the potential that these children may subsequently be (or may have been) diagnosed with inattentive type ADHD.

Type II – With a shortened P300 latency and abnormally high response to non-target stimuli, they suggest that these patients:

“… might be a hypersensitive type with phobia” and that “their nervous system has an abnormal, hypersensitive reaction: a nervous state”.

They further suggest that these patients may be at risk of later developing ‘psychiatric’ conditions such as anxiety disorders.

Subgroups – Will the ‘Real ME’ Please Stand Up?

As previously discussed, the issue of ‘heterogeneity’ has dogged ME/CFS research for decades.

What then to make of objective findings that two subgroups (Types I and II) might exist within a single Fukuda defined cohort that shows abnormal cognitive function but in opposite directions? Remarkably, both groups also show similar deficits in autonomic and frontal lobe function with Type I having more severe deficits, Type III intermediate, and Type II the least affected.

Are these subgroups all part of the same illness but representing different variants e.g., does ME/CFS consist of subgroups analogous to the inattentive, hyperactive or mixed types in ADHD?

Which if any of these subgroups (if any) represents the ‘true ME’ (if such a thing exists)?

Previously I proposed that the ‘Wired and Tired’ ME/CFS type (i.e., the “abnormal, hypersensitive reaction” found in Type II) might be due to a hyperglutamatergic neuroinflammatory state. What, then, to make of the Type I patients with their turned on ‘fight or flight’ response but their hypoactive nervous system functioning?

Do different pathophysiologies underlie these two types or can a single mechanism explain both as well as the apparently intermediate Type III?

Severity?

Some suggest that rather than being discrete subgroups, the various types of ADHD (inattentive, combined and hyperactive) may represent a progressive deterioration with a hyperactive state giving way over time to an inattentive one. This may explain progressively reduced ERP amplitudes found as ADHD patients age (Szuromi, 2011), which reflect lower cognitive efficiency, and may result from a similar neurodegenerative process as found in Alzheimer’s Disease, schizophrenia, and to a lesser extent in normal aging. This might be expected with a (largely untreated) neuroinflammatory vicious cycle.

Similarly, the findings of the comparatively unresponsive nervous system in Type I patients (very low parasympathetic activity, very poor frontal lobe functioning) could reflect not subtypes with a different pathophysiology, but progressive deterioration in brain function which causes the group to pass from the ‘Wired and Tired’ Type II stage to Type I, with Type III being an intermediate stage. This scenario is consistent with a chronic neurotoxic neuroinflammatory state that may lead to progressive disability, and/or a condition that may initially present with variable levels of severity.

A number of studies have identified autonomic dysfunction in ME/CFS and some have associated this with cognitive deficits. This study, however, associates both of these problems with the type of sensory gating/information processing deficits discussed previously which parsimony would suggest are likely to arise from the same underlying pathology.

The relationship between the three measures (or deficits) of course remains to be determined. For example, does autonomic dysfunction lead to a frontal lobe and information processing deficit or vice versa? How do these findings relate to other consistent findings such as systemic inflammation and immune dysfunction?

References

Event-related potentials in Japanese childhood chronic fatigue syndrome

Akemi Tomoda, Kei Miyuno, Nobuki Murayama, Takaka Joudoi, Tomohiko Igasaki.

http://iospress.metapress.com/content/w14pg23t125337q8/

Chronic fatigue syndrome in childhood.

Tomoda A, Miike T, Yamada E, Honda H, Moroi T, Ogawa M, Ohtani Y, Morishita S.Single-

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10761837

Photon emission computed tomography for cerebral blood flow in school phobia

Akemi Tomoda, Teruhisa Miike, Takako Honda, Keiko Fukuda, Yumiko Kai, Mitsuko Nabeshima, Mutsumasa Takahashi

http://www.journals.elsevierhealth.com/periodicals/cuthre/article/PII0011393X9585116X/abstract

Hydrogen Proton Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy in Autism: Preliminary Evidence of Elevated Choline/Creatine Ratio

Deborah K. Sokol, PhD, MD, David W. Dunn, MD, Mary Edwards-Brown, MD, Judy Feinberg, PhD, OT

http://jcn.sagepub.com/content/17/4/245.abstract

FUNDAMENTALS OF MAGNETIC RESONANCE SPECTROSCOPY

John R. Hesselink, MD, FACR

http://spinwarp.ucsd.edu/neuroweb/Text/mrs-TXT.htm

Ischemic Cascade

Wikipedia

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ischemic_cascade

Autonomic Nervous System

Wikipedia

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Autonomic_nervous_system

Activation of dorsolateral prefrontal cortex in a dual neuropsychological screening test: An fMRI approach

Atsumichi Tachibana, J A Noah, Shaw Bronner, Yumie Ono, Yoshiyuki Hirano, Masami Niwa, Kazuko Watanabe and Minoru Onozuka

http://www.behavioralandbrainfunctions.com/content/8/1/26

PACE Manual for Therapists, MREC Version 2

http://www.pacetrial.org/docs/cbt-therapist-manual.pdf

Does the Chronic Fatigue Syndrome Involve the Autonomic Nervous System?

Roy Freeman, MD, , Anthony L. Komaroff, MD

http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0002934397000879

Symptoms of autonomic dysfunction in chronic fatigue

syndrome

J.L. NEWTON, O. OKONKWO, K. SUTCLIFFE, A. SETH, J. SHIN and D.E.J. JONES

http://128.121.104.17/MESA/Newton.pdf

Reduced Cardiac Vagal Modulation Impacts on Cognitive Performance in Chronic Fatigue Syndrome

Alison Beaumont, Alexander R. Burton, Jim Lemon, Barbara K. Bennett, Andrew Lloyd, Uté Vollmer-Conna

http://www.plosone.org/article/info%3Adoi%2F10.1371%2Fjournal.pone.0049518

Attention and short-term memory in chronic fatigue syndrome patients

An event‐related potential analysis

M. K. Scheffers, Drs, R. Johnson Jr., PhD, J. Grafman, PhD, J. K. Dale, RN and S. E. Straus, MD

http://www.neurology.org/content/42/9/1667.short

Research on cognitive complaints and cognitive functioning in patients with chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS): What conclusions can we draw?

Wearden AJ, Appleby L.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8910243

Cognitive deficits in patients with chronic fatigue syndrome compared to those with major depressive disorder and healthy controls

Constant EL, Adam S, Gillain B, Lambert M, Masquelier E, Seron X.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21255911

Cognitive deficits in chronic fatigue syndrome and their relationship to psychological status, symptomatology, and everyday functioning

Cockshell, Susan J.; Mathias, Jane L.

http://psycnet.apa.org/journals/neu/27/2/230

Executive Functions

Wikipedia

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Executive_functions

Mild cognitive impairment (MCI)

The Mayo Clinic

http://www.mayoclinic.com/health/mild-cognitive-impairment/DS00553

Auditory event-related brain potentials in fibromyalgia syndrome

Alanoğlu E, Ulaş UH, Ozdağ F, Odabaşi Z, Cakçi A, Vural O.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14986061

Auditory event-related potential abnormalities in bipolar disorder and schizophrenia

by B F O’Donnell, J L Vohs, W P Hetrick, C A Carroll, A Shekhar

Event-related potentials in major depressive disorder: the relationship between P300 and treatment response

Işıntaş M, Ak M, Erdem M, Oz O, Ozgen F.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22374629

P300 deficits in adults with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: a meta-analysis

Szuromi B, Czobor P, Komlósi S, Bitter I.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20961477

Event-related potential P300 in multiple sclerosis. Relation to magnetic resonance imaging and cognitive impairment

Honig LS, Ramsay RE, Sheremata WA.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/1728263

P300 reduction and prolongation with illness duration in schizophrenia

Daniel H Mathalon, Judith M Ford, Margaret Rosenbloom, Adolf Pfefferbaum

http://www.biologicalpsychiatryjournal.com/article/S0006-3223(99)00151-1/abstract

The P300 component in patients with Alzheimer’s Disease and

their biological children

Brandon A. Ally, Gary E. Jones, Jack A. Cole, Andrew E. Budson

http://www.vanderbilt.edu/allylab/Ally%202006%20P300%20AD.pdf

Event-related potential: An overview

Shravani Sur and V. K. Sinha

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3016705/

Early-stage visual processing abnormalities in high-functioning autism spectrum disorder (ASD)

Joshua M. Baruth, Manuel F. Casanova, Lonnie Sears, and Estate Sokhadze

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3342777/

Reduced cardiac parasympathetic activity in children with autism

Ming X, Julu PO, Brimacombe M, et al.

Autonomic nervous system activity and psychiatric severity in schizophrenia

Fujibayashi M, Matsumoto T, Kishida I, Kimura T, Ishii C, Ishii N, Moritani T.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19496998

Autonomic nervous system in euthymic patients with bipolar affective disorder

Latalova K, Prasko J, Diveky T, Grambal A, Kamaradova D, Velartova H, Salinger J, Opavsky J.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21196931

Depression, the autonomic nervous system, and coronary heart disease

Carney RM, Freedland KE, Veith RC.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15953797

Post-traumatic stress disorder: the neurobiological impact of psychological trauma

Jonathan E. Sherin, MD, PhD, Charles B. Nemeroff, MD, PhD

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3182008/

Pathophysiology underlying irritable bowel syndrome–from the viewpoint of dysfunction of autonomic nervous system activity

Manabe N, Tanaka T, Hata J, Kusunoki H, Haruma K.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19377269

Autonomic Symptoms in Huntington’s Disease – Current Understanding and Perspectives for the Future

N Ahmad Aziz, Raymund AC Roos

Autonomy of autonomic dysfunction in major depression

Koschke M, Boettger MK, Schulz S, Berger S, Terhaar J, Voss A, Yeragani VK, Bär KJ.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19779146

Autonomic dysfunction in unaffected first-degree relatives of patients suffering from schizophrenia

Bär KJ, Berger S, Metzner M, Boettger MK, Schulz S, Ramachandraiah CT, Terhaar J, Voss A, Yeragani VK, Sauer H.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19366982

Dysregulation of the autonomic nervous system predicts the development of the metabolic syndrome

Licht CM, de Geus EJ, Penninx BW.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23553857

Thanks Marco. Very stimulating and thought-provoking, and difficult enough for me to develop my own cognitive problems. I’ll be re-reading this several times. It’s good to know though that Japan is doing some worthwhile research: we do tend to be Western-centred.

:). This was one of the toughest for mje…..How interesting, though, that the sensory gating theory is validated and, although it didn’t explicitly say so, appears tied to former findings of neuroinflammation….How to get that inflammation down, of course, is the big question.

All very interesting but …

Again, another study building upon other studies that lead to no cause, no treatment. I believe this is a perfect example of a study falling in the “gulf” between academia and helpfulness for ME/CFS. Another paper/quill in the professors CV leading him up the ladder towards full professorship or whatever, but no real outcome in the development of drugs to treat the disease.

Another 30 years and counting?

Greg

Yes – to an extent Gregory but I’ve seen too much effort expended on ‘the cause’ – viruses, stress, personality, mould etc etc while the common pathophysiology has been largely ignored as irrelevant or ‘untreatable’.

My own personal feeling is that large, well conducted studies such as this focus in on the key pathology in ME/CFS ” which appears to involve the brain and autonomic nervous system – regardless of the initial cause.

I also personally feel that this gets us much closer to effective treatments rather than constantly looking for ‘the smoking gun’.

One positive aspect is the validation of inflammation being a significant contributor to the neuro-psychological damage (or symptoms thereof). At least it gives us a direction to go in. In addition to treating chronic viruses I test positive for, I am emphasizing anti-inflammatory foods and herbs in my diet. I’ve also been given a prescription anti-inflammatory (Meloxicam) for arthritic pain. Each addition contributes that much more to my ability to feel and function better.

I understand your frustration, Greg. I’ve had it for 30 years and an not sure I’m going to get another 30 and I realize this is it. A diminished life with no treatments that really work. Some people would tell me to be more positive. I won’t post here what I’d tell them. I’m more optimistic when I’m not in a long relapse.

Marco,

Let’s accept the premise that the autonomic system/P300 whatever is affected, as the numerous references have shown. Then lets work on medications that might help relieve the response. The idea being to somehow move forward, rather than confirm what those of us affected know all too well.

Are there any novel drugs that could be used in a trial?

Look at the number of small biotech pharmaceutical companies out there making a fortune working on new drugs. Lets entice the researchers to use them rather than reiterate studies over and over.

Somehow we need to stop the funding of “interesting” but repetitive and nonproductive studies.

We need medications NOW it’s been thirty years. Greg

Hi Greg

That’s exactly the point I’ve been making during this series of blogs.

Although I have to say that, apart from this study, there haven’t been any well conducted studies that have investigated objective evidence of a neurological sensory gating deficit in ME/CFS. There have however been numerous ones in other neurological diseases in which neuroinflammation appears to play a central role. Now many of these other conditions have approved drugs that while not cures may have at least a moderate impact on symptoms or disease progress.

If the same neuroinflammation underpins the ‘state’ of ME/CFS, regardless of how we got into this ‘state’ then is there potential for these already available drugs to impact on ME/CFS?

Personally at this stage I’m happy to settle for a ‘moderate’ improvement in preference to nothing.

Additionally, the fact that these objective measures can identify distinct sub-groups that have cognitive defects that on some measures trend in opposite directions strikes me as more than ‘interesting’. I’d argue findings such as this are fundamental to breaking down the ‘CFS’ wastebasket diagnosis and getting closer to the fundamental underlying pathology and effective treatments which might just be different for different groups. Apart from anything else, if we have distinctively different sub-groups within the ‘CFS’ pot, is it all surprising that findings are often mixed, unrepeatable or dismissed as unremarkable?

I do agree that there are findings which have been repeatedly reported in ME/CFS that could and should be treated now.

One example is autonomic dysfunction. As discussed in the last blog, eminent groups in the USA have stated that autonomic dysfunction in chronic illness needs to be identified and treated as a matter of urgency (and there are available treatments) before it progresses to irreversible autonomic neuropathy which has major implications for morbidity and mortality. With autonomic dysfunction being a consistent finding in ME/CFS are ME/CFS patients routinely screened for autonomic dysfunction and treated accordingly? Why not?

Another example is raised pro-inflammatory cytokines and oxidative stress associated with ‘low grade’ inflammation. These are the few immune findings that ME/CFS researchers can all agree on. There’s also a raft of research on the negative health impact of such a chronic inflammatory state. Again, there are treatments. So what impact would treating chronic systemic inflammation/neuroinflammation have on ME/CFS symptoms? Fluge and Mella are trying out the TNF-a antagonist Etanercept on some patients. I’m not aware of anyone else taking this approach.

Drugs don’t need to be ‘novel’. My last blog identified quite a long list of drugs and compounds with potential to reduce neuroinflammation but they are only going to be considered if researchers consider neuroinflammation as central to ME/CFS.

In contrast to identifying core ‘state’ of ME/CFS and treating it, I personally consider that finding the ’cause’ (that is what triggered it) falls into the ‘nice to know’ category. By now it should be obvious that no one virus, bacteria or other ‘stressor’ was the cause of all cases of ME/CFS and a strong possibility that the ’cause’ may be a unique set of circumstances in each individual.

OK – sensory gating problems, autonomic dysfunction and chronic systemic inflammation are not unique to ME/CFS or useful as biomarkers. So what? How about treating them now and worry about the ‘novel’ and ‘unique’ factors later.

AMEN Greg

My hypothesis for many a long year has been that these illnesses start off with an abundance of steroid hormones with a sympathetic dominance which gradually wears down over the years to a much lower base level of hormones but still with a sympathetic dominance. This results in very different states of the immune system. The gradual wearing down of the steroid cascade results in a higher demand for pregnenolone (known as pregnenolone steal). Pregnenolone is essential for maintaining the glutamate/ GABA balance.

Marco, I love the challenge of trying to understand all of this.

It made me remember something I had read before in regards to some hypothesis in relationship to CFS/POTS patients and what is thought to cause problems with cognitive function. Here are a couple of articles with them suspecting problems with OI (Orthostatic Intolerance) and CFS. It was found that for those with POTS there was a problem with upright posture and cognitive abilities. Since, I feel that we may be looking at the same disorder with CFS, POTS, OI and maybe some other illness – that makes me wonder if the blood flow issue to the brain doesn’t play a bigger part than we realize. There also possibly, could be, hormonal imbalances at play here. And maybe a breakdown in the different methylation pathways or some other faulty genetic pathways that affects bodily functions. Since they were dividing the groups that they tested into three subsets with varying results —how many of that group would qualify to have OI and maybe POTS? Could it all be the same thing – with varying degrees of dysfunction?

I know, with genetic testing, they can now determine if one has genetically inherited the genes for Alzheimer’s and schizophrenia. One can do a 23&me test and find out if it’s in your genetic family line and in your genes to be predisposed to have these things. If that’s a genetically inherited possibility – what could be done to prevent a “turn on of these genetic traits”. If we can find a way to prevent activation of certain things we don’t want to happen – maybe we can prevent a lot of the dysfunction with these other type of illness.

As for using medicines to “tweak” what we may already have – I’m not sure that is the best direction. It would not change things for our offspring – especially if it is a genetically inherited trait and we’re predisposed to have these things because of some genetic weakness. What could we do that might change the function of our bodies and maybe that could be something learned and done by our children and their children – and we don’t become reliant on medicines? That’s assuming that we have inherited a weakness that predisposes us to CFS, POTS and OI? (In my family, there appears to be genetics involved.) Medicines may be a bandaid that we will have to apply until we get to the core issues. And that may be acceptable for a time. But, until we get to the “core” issues and the source of the problem – that will not “fix” the problem.

Quote from Marco —“I’ve seen too much effort expended on ‘the cause’ – viruses, stress, personality, mold etc etc while the common pathophysiology has been largely ignored as irrelevant or ‘untreatable’. My own personal feeling is that large, well conducted studies such as this focus in on the key pathology in ME/CFS ” which appears to involve the brain and autonomic nervous system – regardless of the initial cause. ”

YES —-get to the core problem. Is it genetics that causes autoimmune dysfunction and inflammation causing more dysfunction? And if it is genetic and/or epigenetic changes and we have inherited it – how do we prevent this change? And, how do we “turn it off” (reverse) if it’s already “turned on” (activated)?

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Epigenetic_inheritance

“Foods are known to alter the epigenetics. Epigenetic changes can modify the activation of certain genes, but not the sequence of DNA. Additionally, the chromatin proteins associated with DNA may be activated or silenced. This is why the differentiated cells in a multi-cellular organism express only the genes that are necessary for their own activity. Epigenetic changes are preserved when cells divide. Most epigenetic changes only occur within the course of one individual organism’s lifetime, but, if gene inactivation occurs in a sperm or egg cell that results in fertilization, then some epigenetic changes can be transferred to the next generation.[15] This raises the question of whether or not epigenetic changes in an organism can alter the basic structure of its DNA .”

What is the key with the function of our bodies? Is there a deficiency in an enzyme or vitamin or amino acid? Is there some breakdown in the way our body processes things and that is causing the breakdown? We know we inherited imperfection and we were all born dying. But, is there something that we can do to make the quality of our life better and whatever quantity of life we have left more enjoyable?

I copied a little bit of these three articles so you could get the jest of them.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3368269/?report=classic

Our results show that CFS/POTS subjects do not have differences in intelligence, but rather experience cognitive impairment mainly due to the effect of orthostatic stress, especially during difficult tasks.

http://www.frontiersin.org/Integrative_Physiology/10.3389/fphys.2013.00113/full

Therefore, patients with CFS may not have difficulty with memory per se, but rather with information is presented to patients with CFS too quickly the information is unlikely to be processed. In fact, Cockshell and Mathias (2013) found that when compared to healthy controls, patients with CFS showed impaired information processing speed, yet demonstrated similar performance on tests of attention, memory, motor functioning, verbal ability, and visuospatial ability. Again, this finding demonstrates that cognitive dysfunction among patients with CFS is related to impaired information processing rather than memory difficulties.

Recent research has begun to examine neurocognitive impairments in patients with POTS, primarily difficulty with working memory and information processing. In order to examine the relationship between cognitive dysfunction and POTS, Stewart et al. (2012) had participants complete and N-back task while on a tilt-table. The test is designed to increase orthostatic stress.. Stewart et al. (2012) found increasing orthostatic stress in patients with CFS/POTS was related to poor performance This demonstrates neurocognitive impairment for patients with CFS/POTS. Current theories which aim to explain cognitive difficulties among patients with CFS and/or POTS are discussed below, including kindling theory, central nervous system impairments, difficulties with blood flow, and impairment with a number of neurotransmitters.

One theory that has emerged suggests that cognitive impairments and mental cloudiness associated with POTS is associated with cerebral blood flow. Similarly to CFS, this results from a program with the central nervous system. Substantially lowered cerebral blood flow occurs about 50% of the time in patients with POTS when compared to controls. The lower cerebral blood flow can impair cerebral perfusion and neurocognitive function (van Lieshout et al., 2003). A significant decrease in brain perfusion could potentially explain lightheadedness, dizziness, and mental cloudiness that are common among patients with POTS (Low et al., 1999; Schondorf et al.,

Other studies report CFS and POTS symptoms are directly related to abnormalities of central neurotransmitters including corticotrophin-releasing hormone (CRH) (Demitrack et al., 1991; Bakheit et al., 1992; Sharpe et al., 1996). The main function of CRH is to produce behavioral and locomotors function. Deficiency of CRH could explain chronic fatigue, and in turn, cognitive impairments associated with chronic fatigue.

It is clear that understanding cognitive impairments and symptoms in CFS and POTS is not a simple task. However, the common theme suggests some sort of impairment within the central nervous system. Further research should focus on the central nervous system as a possible gateway of understanding the etiology of these disorders further.

http://ajpheart.physiology.org/content/302/5/H1185.full

chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS) is associated with orthostatic intolerance (OI), especially in the young (21, 49). OI is defined by signs and symptoms such as dizziness, fatigue, tachycardia, hypotension, visual disturbances, hypocapnia, headache, cognitive deficits, and nausea while in the upright position that is relieved by recumbence (46, 55). In CFS, OI often takes the form of postural tachycardia syndrome (POTS) (27, 54) or neurally mediated hypotension

It has been hypothesized that impaired cerebral perfusion contributes to the neurocognitive dysfunction in CFS/POTS subjects. We hypothesized that the postural cognitive loss in young CFS/POTS patients is due to orthostatic reductions in CBF related to abnormalities in cerebral vasomotor tone (16) and reduced neuronal activation of CBF reactivity (48). We propose that during cognitive tasking, the blood flow response to neurocognitive tasking is suboptimal and is related to increased vasomotor tone, suggesting deficits in the neurovascular unit (comprising functional interactions among the neurons, blood vessels, and glia)

Young patients with CFS may not all have POTS. However, the consensus among investigations of pediatric and adolescent subjects with CFS suggests that almost all young CFS patients have OI.

Issie

Hi Issie

Thanks for the comments and links.

I’m very much in agreement. The papers you linked to all talk about POTS being a spectrum with numerous causes (inc diabetes) and considerable overlap with ME/CFS, fibro etc. I read somewhere that around 50% of POTS patients (those with POTS ‘only’ and not for example ‘co-morbid’ CFS) have peripheral neuropathy – a similar percentage to fibromyalgia patients. I’m not sure peripheral neuropathy has been tested in ME/CFS – perhaps it should be?

So we have a cluster of overlapping symptoms and conditions that include (at least) POTS, fibromyalgia, ME/CFS and diabetes.

I don’t think I mentioned previously but the first time I realised something physical was wrong was, as a very fit 20 something I fainted during Ju Jitsu warm up training where we were doing exercises with the arms above shoulder level. I still have problems doing anything above shoulder height e.g. if changing a lightbulb (sounds like a joke) – if doesn’t come out and go in easily I really start to struggle and my arms become like lead and my head swims etc. 1 minute or so of that and I’m finished.

Blood flow could certainly be a major factor in reduced cognition as the ischemic cascade leads to increased extracellular glutamate (and reduced information processing efficiency).

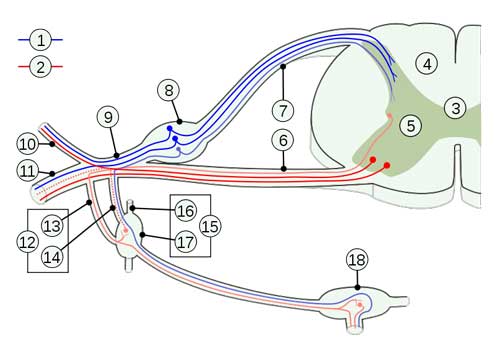

I’ve tried to summarise the model I’ve been suggesting in these blogs graphically which I’ll try and attach below.

Essentially (given certain predisposing factors) a variety of stressors induce increased pro-inflammatory cytokines. PICs such as TNF-a can kick of a neuroinflammatory vicious cycle through the attenuation of extracellular glutamate clearance by astrocytes (plus activated microglia also pump out pro-inflammatory cytokines. The result is a potentially self sustaining cyle of neurotoxic extracellular glutamate, oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction.

This neurotoxic state causes dysregulation and potentially neurodegeneration, affecting pre-frontal inhibition (of sensory input) and of the sympathetic nervous system. Peripheral and autonomic neuropathy may also result. POTS may be one result of autonomic dysfunction.

As the parasympathetic nervous system activity is anti-inflammatory, a sympathetic dominant state may contribute to an inflammatory state and therefore the whole cycle kicks off again and may be self sustaining even when the original ‘stressor’ is gone.

Does this sound compatible with your own thinking?

A neuroinflammatory model of ME/CFS

Notes :

A neuroinflammatory cycle may be triggered by a variety of infective, physiological or psychological stressors in individuals with genetic of acquired predispositions.

Pro-inflammatory cytokines (potentially via attenuated clearance of extracellular glutamate by glial cells) trigger a ‘vicious cycle’ of neuroinflammation which in itself may be self-perpetuating via ‘feed- forward’ mechanisms / ‘kindling’. The neuroinflammatory cycle depletes antioxidant capacity which feeds back as a perpetuating ‘stressor’.

Neuroinflammtion may result in neural loss in the pre-frontal cortex compromising inhibitory mechanisms resulting in deficits in executive function, attentional mechanisms, working memory, sensory gating and vagal tone which in turn results in a state of autonomic nervous system ‘sympathetic dominance’. Neuroinflammation may also result in peripheral and autonomic neuropathies.

Together these mechanisms result in increased pain and nociception, fatigue, exercise intolerance, postural hypotension etc. Again these effects feed back as perpetuating stressors.

Chronic sympathetic dominance is associated with reduced GABA, reduced stress resilience, reduced immune function (which may allow viral persistence) and is essentially a pro-inflammatory state increasing oxidative stress and the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines which in turn further stimulates the neuroinflammatory cycle.

Persistent sympathetic activity may attenuate the production of protective (against ROS and glutamate excitotoxicity) heat shock proteins (HSPs) – a degenerative deficit also found in ageing.

This model is potentially self sustaining at the neuroinflammation level and as a global system.

Yeah. I want a drug. I want it NOW. ‘Inflammatory process’, known to be progressively damaging, is a good place for said drug to begin. Add all the other drugs you want. But find ONE anti-inflammatory and apply it to all and see if anything noteworthy happens. Forget cohorts, etc. We are bogged down in cohorts, Many of us are aging so that we are at risk for death. What causes DEATH? The, uh, heart stops beating. I vote for giving life a chance. I’ve spent half my own lifetime reading studies and yet meanwhile we are all still ill, some of us dead.

I think the key driver is the autonomic overactivity respons. This lead to reactivation of infections like herpesviruses. It is well know that ”stress” leads to reactivation of EBV etc… Nancy klimas also thinks the ANS respons is the key driver of immuneproblems. I think the parasympathic nervous system is broken (genetic, autoimmunity or infection?) which cause the overdrive respons and vicious circle in ME/CVS. It is a ”stress” disease (Kogelnik) problem not mentally but the system (physical) is defect.

I’ve been an occasional visitor here for the last 1-2 years, and I’ve always maintained CFS is ‘all in the brain” (and CNS!).

All respect to Klimas et al who’ve certainly been persistent, but they’ve been barking up the wrong immune tree for far too long. Tried all sorts of immune treatments with limited impact.

Andrew Lloyd in my own country of Aus has been getting close I feel, with the brain.

there are certainly several potential drugs that could be tested NOW, and I agree with others here that we need to see action.

BTW has anyone else seen good results with prozac like I have. Studies show it reduces neuroinflammation, cytokines in the brain etc. (ie. it’s positive effects in me may be more to do with neuroinflammation than depression)

Be careful with Anrew Loyd. He things ME/CVS is a psychosomatic syndrome.

People cut the nonsense! The Nicolson’s have already proven it’s Mycoplasma fermentans incognitus. The Government did this to us for population control. Read Project DAY Lilly by Professor Nicolson and his Wife Dr. Nicolson. Both my parents died at 65 and 67 from Pancreatic and Byle duct cancet. Mycoplasma fermentans incognitus is contagious and I believe they caught it from me. Professor Nicolson didn’t know if it caused there cancers but he discovered people with cancer that had mycoplasma fermantans incognitus would not survive their cancer as opposed to cancer patients that didn’t!

All quotes from Marco, that sum up nicely the probable cause of what is going on:

By now it should be obvious that no one virus, bacteria or other ‘stressor’ was the cause of all cases of ME/CFS and a strong possibility that the ’cause’ may be a unique set of circumstances in each individual.

A neuroinflammatory cycle may be triggered by a variety of infective, physiological or psychological stressors in individuals with genetic of acquired predispositions.

Blood flow could certainly be a major factor in reduced cognition as the ischemic cascade leads to increased extracellular glutamate (and reduced information processing efficiency).

As the parasympathetic nervous system activity is anti-inflammatory, a sympathetic dominant state may contribute to an inflammatory state and therefore the whole cycle kicks off again and may be self sustaining even when the original ‘stressor’ is gone.

Chronic sympathetic dominance is associated with reduced GABA, reduced stress resilience, reduced immune function (which may allow viral persistence) and is essentially a pro-inflammatory state increasing oxidative stress and the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines which in turn further stimulates the neuroinflammatory cycle. ________________________________________________

AGREE, AGREE, AGREE!!!! I think first we are genetically predisposed to certain possible illnesses or genetic defects (considered illness) and then something triggers an epigenetic change in a negative direction (dis-ease) be it a virus, vaccine, stress, accident with injury etc. That change becomes something we somehow continue to cycle (with our diet, lifestyle, stresses, attitudes towards it or life, etc) that imbalances even further what may be a genetic flaw with how our body processes different pathways of functioning (methylation, hormones, etc.). We ignorantly continue this dysfunction with (diet, lifestyle choices, etc.) We raise our kids with these same flaws in the same dysfunctional way that we are (not) managing ourselves and they learn our “habits”. That mutation of possible epigenetic change (debate as to whether that change could possibly with time change DNA) continues to be multiplied with each generation. Where do we stop it? We have to make lifestyle changes and change into a positive direction – that which we keep repeating in a negative reaction. BUT . . . . here’s the BIG —-BUT, how many people are willing to do it? More people are looking for a drug that they can swallow down – masking the problems, not correcting a blame thing. Passing it on to the next generation and them on to the next and the human race and mankind continues to deteriorate —because either by ignorance or lack of will they can’t seem to make the needed lifestyle changes to halt what is happening. Uh Oh, I’m starting to have a rant. LOL! I just don’t think that people medicating themselves into a zombie like state, masking the problems is going to fix anything. It may give some emotional and physical relief. But, long term —it’s not going to get to the “core” problem. We have to figure out how to be more proactive and less reactive. To be proactive we don’t react with the easy fix. But, work out what could eliminate the problem in the first place.

Marco, that for sure sounds like POTS. We can not do things above our heads. Even washing our hair is a problem. I have to sit in a shower to bathe and wash my hair and that takes plenty of time – because of having to use my arms. Cort has allowed me to have a blog that he has started that describes POTS with some videos that have been provided by DINET and also a member there. The links that I list take you to the DINET forum where we are discussing this one members video – as some things were left out and some of us questioned a few things that was said in it. Take a look at this blog and the videos and let me know what you think. I’m sure there is much more that needs to be added – but, the videos will give you a good overview.

http://www.cortjohnson.org/blog/2013/07/23/animal-model-breakthrough-increases-our-understanding-of-pots-points-to-new-therapeutic-targets/

Yes, Marco – to answer your question –I think we are thinking along the same lines.

Issie

Thanks Issie

Does sound like POTS doesn’t it?

I do also feel that diet plays a part. I’ve felt much better (not well, but less not well) since cutting all the crap (pardon my French) such as pre-prepared meals from my diet.

Good to here you’ll be blogging more on this – I look forward to it.

I do feel that we are looking at different facets of the same underlying problem.

PS – Forgot to ask and I am interested. Any idea what the genetic predisposition to Alzheimers’ was?

PPS – Sorry. Still haven’t worked out how to embed a graphic in a comment.

Good to here you’ll be blogging more on this – I look forward to it.

http://www.cortjohnson.org/blog/2013/07/23/animal-model-breakthrough-increases-our-understanding-of-pots-points-to-new-therapeutic-targets/

Here it is. I don’t want my own blog – so Cort is letting me use his.

As for the gene with Alzheimer’s I’ll have to go back and look at my 23&me info and pull up the gene. It has it’s own space on the testing and they will tell you if you inherited the gene for it. People can choose whether or not they look at the results —as some people rather not know. I inherited all kinds of stuff – but, I want to know – because maybe I can do something about it. They will do testing of people from other countries and it’s well worth the $99.00 US to have it done.

Good you are trying to make diet changes – as I really believe that is our key. Food should be our medicine. I have changed how I look at supplements, as before I felt the more the better and if one was seemingly deficient in something – take a supplement. I still believe in supplements (especially for those that are not willing to make lifestyle changes) but think that we will get more benefit from trying to get what we need with our food —FIRST. And then supplementing with whatever we may need after we try that approach first. Your body has to process whatever you put into it. A concentrated supplement – may be too much for an already weakened body. We may not need as much as we think, if we process it the way we should. I’m slowly being able to cut way back on what I once felt has kept me alive and going. Food choices do make a difference with health. I do feel that working on any known methylation dysfunctions (which can also be done with diet, but may require a small amount of certain supplements) is also beneficial.

I also feel that working on the immune system is the next step. Then also addressing inflammation. I think if we work on those things – that will probably be the best we can do for ourselves.

Issie

Marco,

Did you look at the videos that I posted on POTS? Does any of it fit with your symptoms? POTS is determined by what your heart rate does when you stand up. If it goes from lying baseline – up by 30 points or goes above 120 with standing – then you can suspect POTS. Many people don’t notice huge changes in their blood pressure. There are those that have really low pressures and others of us that have high pressures —and also some of us that have liable blood pressures – where there are extreme swings in both directions. If you tend to have a drop in you bp with standing and don’t have the rise in hr that is considered OI (Orthostatic Intolerance). It’s still a form of dysautonomia. There is a test that you can do yourself to somewhat figure out if this is a problem —called a “poor man’s tilt test”. You do this by lying down for a bit and checking your blood pressure while lying and resting. Then when you stand – within 10 min. if you have the above results with a hike in your bp by 30 points or it goes above 120 – then you should talk to a electro cardologist or a neurologist that deals with the autonomic system, and determine whether or not you have POTS.

Issie

Sorry Issie

I haven’t as yet as I have very slow broadband and streaming videos is usually a frustrating exercise.

Thanks though for the ‘POTS primer’.

I don’t have access to a BP monitor but I’ll have to check my pulse when ‘orthostatically challenged’.

BTW – Does bending over tend to increase symptoms and do POT patients get a feeling of simultaneously lightheadedness and ‘brain inflammation’ which increases as the day goes on?

Some people notice problems with bending over – like lots of pressure in their heads. It can also make someone feel dizzy. We all present with such different symptoms.

As for “brain inflammation”, not sure what you mean by that. If you want to go into a little more detail, maybe I can answer that better. As I can think of a lot of things that I’d consider as symptoms for that one.

It’s important to know what your bp (blood pressure) is doing in addition to your hr (heart rate). It can determine better what you may need to consider. That’s one thing that we POTS people invest in. Maybe someone would have one that you could borrow. Do you notice more problems when you stand? That’s when most of us have the most problems. I can walk around better then standing in place. I need to keep moving or fidgeting – it keeps my blood moving better and helps to prevent the dizzies and the orthostatic part of POTS. I have HyperPOTS and my sister has OI (Orthostatic Intolerance) We both have similar symptoms – yet so different.

If you could take a look at those videos – it would give you a feel for what POTS is. There are those that faint and those that don’t. Thankfully, I’m not a fainter – just come near to it at times. There is a lot of technical information that I think you’d like – you appear to be like me and like that sort of thing. I want to know “WHY” things are the way they are. I’m not content with just knowing what I have that I’m dealing with. The more I learn, the more I realize I don’t know. It has been an interesting learning experience and journey!

Issie

Re : ‘brain inflammation’ – its difficult to describe which is why i used such a vague term. The feeling does increase during the day and may well be related to ongoing activity/being on my feet.

There is lightheadedness (that is a mild feeling of unsteadiness) but my head also feels full and burning – as described before as ‘brain on fire’.

I also have burning eyes and what feels like burning mouth syndrome which may be related to neuropathy.

I don’t know if that clarifies anything?

… and yes, I’m definitely someone who likes to know why!

Thanks again.

When my blood pressure is up – usually with standing – my head has that pressure feeling and my eyes feel like they have too much pressure behind them. That is likely blood pressure related. But, I also have tachycardia – which is a rapid heart beat. It can go as high as 156 beats from just rising from a chair. That’s not doing anything – just standing. There is definitely a dizzy sort of blurry feeling. It’s like the world blurs and you feel sort of an unsteadiness and like you can’t judge distance (if you’re walking). Sort of like your glasses are too strong and it affects your stomach with a bit of a nauseous feeling in your stomach and a feeling like I have to sit down right this minute or this is going to be BADDDDD. Most likely when I feel this way – there has been a drop in my blood pressure (this is the orthostatic part of it) and the tachycardia will start to try to bring my blood pressure up. With me with the higher pressures my drops could just bring me into a more normal blood pressure range (or it could be a significant drop) but, the body doesn’t like this drop and tries to bring it back up – even when it may be too high to start with.

A lot of people have their blood pressures drop with hardly any rise in heart rate – that is Orthostatic Intolerance.

There are other POTS people – the majority- that have lower blood pressures and don’t get the rise with their blood pressure, that I do, but within 10 minutes have a significant rise in heart rate. Everyone has a little bit of a rise when they stand up —but, 30 points or above is considered – NOT normal as is anything over 120 beats without exertion or exercise.

When I hear burning mouth the first thing I think of is sojourns. It can cause that – as my mom has sojourns and has really bad burning mouth and painful eyes because they are too dry. But, there are those that have neuropathies and that can be related to what you describe also. Many people that are finding they have neuropathies are connecting autoimmune issues to that and sojourns is also autoimmune.

Not sure what your healthcare system is like where you live. But, there are several things you could check out.

It will be hard to know until you know what your heart rate and blood pressures are doing as to whether or not there is some sort of dysautonomia going on or not. As I said before, we all present so differently. But, I truly believe that we may find, with time, that working on our immune systems will probably help with much of it.

Issie

Marco said that the parasympathetic ns was anti-inflammatory. How can that be when cortisol is anti- inflammatory and is overproduced in a state of sympathetic dominance? Suppressed inflammation results in a suppressed immune system and thus opens the way for viruses to re-establish.

Hi Tricia.

I’m probably oversimplifying things (I don’t have a biological science background) and I would expect any interaction between the ANS and immune system to be complicated.

As appears to be the case in a review of such interactions in rheumatoid arthritis from which the following excerpt (my bolds added) is taken (and explains much better than I can) :

Like RA – doesn’t the bulk of evidence suggest that ME/CFS folks have sympathetic dominance and low cortisol?

Restoring the Balance of the Autonomic Nervous System as an Innovative Approach to the Treatment of Rheumatoid Arthritis

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3188868/

It appears to be the case that sympathetic dominance or increased sympathetic tone in these diseases will result in a continual overproduction of cortisol with subsequent serum alkalosis and suppression of the immune system. I was interested to read in your article that it is believed that the HPA axis becomes uncoupled from the SNS in this case, obviously a natural mechanism to prevent this state of affairs from continuing. However, the resulting low level of cortisol will leave the way open for increased levels of inflammation, despite other parts of the SNS being active. I still can’t see how the PNS could be anti-inflammatory as low levels of cortisol result in an over active immune system. The state of sympathetic dominance without the assistance of the HPA axis leaves us in a pseudo-parasympathetic state, another words minus the anti-inflammatory cortisol, despite an overall sympathetic tone. BP would also be down in a PNS dominant state, along with cognition. Both I believe are related to the level of cortisol. I have experienced both an over active immune system (no viruses or infections for almost 10 years) and also very low BP ( often dropping to 80 over 50). My cognition drops to zero when BP down. However, now that I take a large dose of pregnenolone (precursor to progesterone and cortisol, and a neurosteroid), my BP systolic rarely falls below 100 and my cognition has improved significantly. I am much more physically and mentally active without the severe crashes I used to have. Pregnenolone is believed to be able to keep cortisol levels moderated and perhaps it does this by getting the HPA axis back on track.

Very interesting Tricia.

I’ve tended to see SNS mediated high cortisol levels in response to stressors as an acute emergency response but that a chronic stressor will result in reduced cortisol – perhaps via this HPA axis uncoupling.

These authors, if I picked them up correctly, suggest that the anti-inflammatory effects of the PNS are via a separate vagal ‘cholinergic antiinflammatory pathway’.

An ‘overactive’ (or at least elements of it) immune system seems to also fit my experiences. Last winter I had my first recognisable common cold in nearly three decades. Most of the time I feel fluey anyway and probably wouldn’t notice any additional symptoms. I’m also not aware of ever getting any of the usual bugs and viruses going around.

What I do find is extremely bad reactions to insect bites, solvents etc.

In addition to modulating cortisol levels, progesterone may also be directly neuroprotective :

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23639063

“To study progesterone effects in neuroinflammation, we employed mice with experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE).

EAE mice spinal cord showed increased mRNA levels of the inflammatory mediators tumour necrosis factor α (TNFα) and its receptor TNFR1, the microglial marker CD11b, iNOS and the toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4).

Progesterone pretreatment of EAE mice blocked the proinflammatory mediators, decreased Iba1+ microglial cells and attenuated clinical signs of EAE.

Therefore, reactive glial cells became targets of progesterone anti-inflammatory effects.

These results open the ground for testing the usefulness of neuroactive steroids for neurological disorders.”

You guys are talking about two different hormones. (1) pregnenolone (2) progesterone. They both affect GABA balance. Some people have paradox reactions with both and it depends on the level that you take in relationship to other hormones in the body as to your response. Here’s one article explaining this.

http://www.medref.se/pms/backstrom_13.pdf

I’ve often questioned estrogen dominance as one factor. We get so many xenoestrogens in our bodies these days and there is bound to be an imbalance in both men and women.

That said, I had a complete hysterectomy at a very young age and could not take progesterone either before or after. I would have that paradox reaction and it stimulated the sympathetic system and caused agitation, anger etc. I could not use it.

However, if you look up pregnenolone and progesterone – they both seem to affect GABA function.

Issie

Hi Issie

That ‘U-shaped’ action appears to be common with neurotransmitters, both low and high levels have negative (paradoxical) effects.

Re : estrogen dominance – in an apparently female dominated condition such as ME/CFS I do wonder about us men who do all seem to have hormone issues.

I’ve often if we might be ‘fast aromatisers’ (testosterone to estrogen) and whether this might be a predisposing factor in males?