“Our results provide evidence of neuroinflammation in CFS/ME patients, as well as evidence of the possible contribution of neuroinflammation to the pathophysiology of CFS/ME.“

‘Show Me the Inflammation!’

It’s perhaps emblematic of a complex and difficult to nail down illness such as ME/CFS or CFS/ME (aptly illustrated by this uneasy compromise) that even the name has been a source of ongoing rancour since early clusters were attributed to outbreaks of epidemic ‘encephalitis’ or examples of mass hysteria.

In fact the ‘itis’ in myalgic encephalomyeltis has often been an easy target for those wishing to downplay the seriousness of the condition. The inability over many years to unambigously show encephalomyeltis (inflammation of the brain and spinal cord) made it difficult, to say the least, to counter the growth in usage of the unfortunate term chronic fatigue syndrome (or often just chronic fatigue). Even the UK ME Association’s own Dr. Shepherd has lately taken the pragmatic approach of using ‘encephalopathy’ rather than get into nitpicking arguments over terminology.

The 2014 IACFS/ME Conference may have just put ‘itis’ of the brain right back center stage. Komaroff’s Highlights of the IACFS/ME 2014 Conference Last month at the close of the IACFS/ME conference Professor Anthony Komaroff provided his customary end of conference summary followed by an audience Q&A session. Komaroff is known for his sober and measured assessment of emerging research, but even he was enthused at various parts of his presentation.

Focusing on the Brain

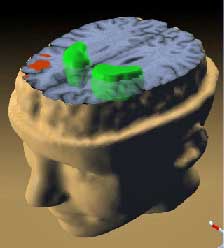

Two aspects of the brain session particularly piqued his interest; Stanford researchers using quantified QEEG were able to distinguish ME/CFS patients from healthy controls with remarkable accuracy, while a Japanese group was able to show objective evidence of activation of the brain’s resident immune cells – a key indicator of neuroinflammation. Commenting on these findings (comments compiled by Margaret Williams and posted at MEActionUK) Komaroff stated:

“There is, and you’ve heard it repeatedly in the last three days, a theory that CFS might reflect an ongoing activation of immune cells in the brain, not in the periphery, but in the brain”

In the Question and Answer session, Komaroff was asked if neuro-inflammation was not encephalomyelitis, to which he replied:

“Yes. If it were confirmed by multiple other investigators it would, for me, say that there is a low-grade, chronic encephalitis in these patients, that the image we clinicians have of encephalitis as an acute and often dramatic clinical presentation that can even be fatal has – may have – blinded us to the possibility that there may be an entity of long-lasting – many years long – cyclic, chronic, neuro-inflammation and that that underlies the symptoms of this illness”, commenting that it was “entirely plausible and these data are consistent with it”.

“A Small But Perfectly Formed Study”

This was quite a dramatic response from one not normally given to hyperbole. So what exactly did the Japanese researchers find and what does it mean?

This small study (9 ME/CFS patients – Fukuda) and 10 age and sex matched healthy controls, resulted from a collaboration between RIKEN, Japan’s largest comprehensive research institution which is renowned for its high-quality research in a diverse range of scientific disciplines, Osaka City University, and Kansai University of Welfare Sciences. Despite the small sample size the institutes were sufficiently impressed to issue a press release which was picked up by Science Daily amongst others.

The primary aim of the study was to look, for the first time in ME/CFS, for direct objective evidence of neuroinflammation – inflammation of the nervous system – in the brain.

They injected a compound that binds to a protein released during activation of the brain’s resident immune cells (microglia and astrocytes) – a key sign of neuroinflammation – and then used PET (positron emission tomography) scans to detect the binding that occurred. High levels of neuroinflammation created levels of high intensity in the scan. Neuroinflammation was measured for the whole brain and special ‘areas of interest’ – key brain areas known to be associated with some of the key ME/CFS symptoms.

The researchers also measured cytokine levels in whole blood (TNF-a, IFN-gamma, IL1b and IL6) and collected self-reported data on measures of fatigue, pain, cognitive dysfunction, and depression to determine if neuroinflammation in these key brain areas correlated with symptoms.

Why They Looked for Evidence of Neuroinflammation

Several lines of circumstantial evidence that are suggestive but are not direct evidence of neuroinflammation in chronic fatigue syndrome include:

- ‘Neuropsychological’ symptoms (cognitive impairments, widespread pain, and depressive symptoms) suggest involvement of the brain in the pathophysiology of ME/CFS;

- Previous PET studies by the same team showed brain hypoperfusion and reduced synthesis of various neurotransmitters (glutamate, aspartate, GABA, acetylcarnatine, and serotonin transporters) in various brain regions while neuroimaging has suggested that reduced volume in the prefrontal cortex is associated with severity of fatigue;

- Other fatigue related diseases such as MS, Parkinson’s, and post polio fatigue arise from brain dysfunction with neuroinflammation thought to play a key role;

- Reported elevated levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines, either in peripheral blood or in cerebrospinal fluid, may reflect neuroinflammation.

Key Findings

- Needless to say ME/CFS patients had significantly higher levels of fatigue, pain, cognitive problems, and depression than healthy controls although levels of depression were below that required for a clinical diagnosis;

- Neuroinflammation in the brain overall was higher in ME/CFS patients than in healthy controls;

- Neuuroinflammation was higher in the key brain areas – the cingulate cortex, hippocampus, thalamus, midbrain, the pons, and the amygdala (many of which have previously been implicated as playing a role in ME/CFS and FM);

- Of the four proinflammatory cytokines measured only circulating levels of peripheral IFN-gamma were higher (but not significantly) in ME/CFS patients;

Neuroinflammation correlates with symptoms.

- The peak value reported in the patients in the ‘intraluminal nucleus’ of the left thalamus correlated positively (significantly) with cognitive impairment scores with a trend (not significant) correlation with fatigue. The findings in this brain area (and the midbrain) which are involved in the ‘reticular activating system’ (which plays a role in arousal) mirrored the Stanford qEEG study findings of disrupted ascending arousal systems reported in the same session);

-

Inflammation of the amygdala (which monitors incoming sensory information and modulates attention) was correlated with cognitive impairment;

- Self reported levels of depressive symptoms were correlated with neuroinflammation in the hippocampus (implicated in mood disorders);

- Inflammation in the thalamus and cingulate cortex was associated with pain. This accords with a previously reported interaction between the cingulate cortex and thalamus in pain suppression.

Taken together, these findings provided clear evidence of an association between neuroinflammation and the symptoms experienced by ME/CFS patients.

Interpretation

The researchers offered two possible mechanisms by which the neuroinflammation found may relate to ME/CFS:

- (a) Overactive neurons are driving the neuroinflammation. This possibility suggests patients have to exert greater efforts in these parts of the brain to overcome the daily functional limitations associated with ME/CFS. (This mirrors reports that ME/CFS patients use a much larger area of the brain than normal to process information). Overactivated neurons in turn trigger the glutamate receptors to release proinflammatory cytokines and neurotoxic factors that generate oxidative stress. In this scenario neuroinflammtion may be secondary to some other pathophysiology but may also contribute significantly to symptoms.

- (b) The immunological response to an initial infection that induces the production of proinflammatory cytokines and oxidative/nitrosative stress leads to neuroinflammation, which suggests that ongoing infection may not be a prerequisite for self-sustaining neuroinflammation.

Evidence of ‘Encephalomyelitis’ – Is this the smoking gun?

Do these findings then finally validate the name Myalgic ‘Encephalomyeltis’ thereby consigning ‘chronic fatigue’ to the historical dustbin? My view is that they do not – but they may pave the way to a better and more productive understanding of the underlying pathology of what is likely to be a heterogeneous disorder. The crux of the problem lies in the framing of the historical debate between users of the terms ME and CFS and in the nature of neuroinflammation.

Polarized Views

As stated in the introduction, two views have tended to predominate in the debate about the nature and the name of ME/CFS.

Drawing on the clinical similarities between the Royal Free outbreak and previous outbreaks of encephalitis and poliomyelitis, one view clearly proposed a discrete disease, probably infectious and with the various neurological symptoms likely to result from the infection causing inflammation in the brain and spinal cord – hence ‘Encephalomyelitis’. A small number of post mortem examinations provided some support for this model. The result has been the ongoing hunt for ‘the’ pathogen underlying ‘ME’ which eluded investigators at the time.

The alternative view, citing the subsequent lack of clear evidence for inflammation of the brain or a single causative pathogen, instead proposed models where infections may play only an initial role but where the ‘syndrome’ is perpetuated largely by psychological factors – citing frequent ‘co-morbid’ mood and anxiety disorders as supporting evidence.

Neuroinflammation – A Different Kind of Brain Injury

Should we have expected to find gross physical changes to the brain? Acute ‘insults’ to the brain such as traumatic brain injury or viral encephalitis may result in an acute phase inflammation with gross structural changes such as edema (swelling) or distinct lesions that may be readily apparent using structural imaging techniques such as MRI scans.

In contrast, ‘neuroinflammation’ generally concerns a much more subtle chronic, low-grade and sustained activation of the brain’s resident immune (glial) cells associated not with acute traumatic brain injury or acute viral encephalitis but with the long term sequelae of brain injury or infection, autoimmune diseases, normal aging, neurodegnerative diseases such as Alzheimers’ and Parkinson’s, and ‘classic psychiatric’ disorders such as major depression, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, and OCD. Microglial activation has also been reported in association with stress/anxiety, with diabetes, and with neuropathic pain.

Neuroinflammation is not easily detected using the structural imaging techniques used heretofore in this disorder because it may result in damage too small or subtle to be imaged or may not result in structural changes. It can still, however, cause functional, metabolic, or even temporal dysfunction between various brain regions.

Neuroinflammation qualifies as inflammation of the brain (an ‘itis’), then, but not the type originally described by ‘encephalomyelitis’. It describes a type of ‘encephalomyelitis’ that scientific and technological advances have only recently identified as underlying a wide range of conditions.

Going Forward

The researchers concluded that they have provided evidence for neuroinflammation in ME/CFS. The fact that inflammation in key brain regions correlates with ME/CFS symptoms suggests that neuroinflammation may contribute to the underlying pathophysiology.

They further suggest that:

“our results demonstrate the usefulness of PET imaging for the development of objective diagnostic criteria, evaluation of disease severity, and effective medical treatment strategies using anti-inflammatory agents in CFS/ME.”

Replication/Validation

Validating or duplicating the original results will be critical, but the authors appear confident this will be done.

Of course, all of this depends on these results being replicated with a larger sample and preferably independently replicated by another institution using a different cohort. The press release suggests that Dr. Yasuyoshi Watanabe, who led the study at RIKEN, is confident that will happen. He stated

“We plan to continue research following this exciting discovery in order to develop objective tests for CFS/ME and ultimately ways to cure and prevent this debilitating disease.”

The team has already started follow-up studies (a) to examine the possible impact of neuroinflammation on serotonin transport, and (b) they report that they are currently performing a ”next-phase international collaboration study”.

The international collaboration may be critical, as these studies are costly (reportedly in the region of $10,000 per patient – hence the small sample size) so are unlikely to be viable for small research teams.

Other Markers of Neuroinflammation

Smaller research teams needn’t be totally excluded, though. As detailed earlier, this study was initiated in response to converging evidence that was compatible with neuroinflammation. Other markers of neuroinflammation may be found (and may already have been recorded in the existing literature) without the need for PET scans (which are expensive and still not widely available).

Neuroinflammation, like all metabolic processes, may leave chemical traces (metabolites) that can be compared to healthy norms. For example elevated levels of the metabolite quinolinic acid in cerebrospinal fluid may be indicative of neuroinflammation. Other objective ‘epiphenomena’ such as impaired sensorimotor gating are associated with a range of conditions in which neuroinflammation is now suspected of playing a key role.

A Paradigm Shift?

Does this study provide a missing piece? Further studies, which appear to have already begun, will tell.

At the very least, the possibility that neuroinflammation may play a central role in the pathophysiology of ME/CFS opens up new areas of investigation and provides a new lens through which to interpret previous findings and may suggest new possibilities for treatment. Who knows, for instance, how neuroinflammation of the ME/CFS brain would look following physical or mental challenges?

- Check out Marco’s blogs on Neuroinflammation and ME/CFS here.

Like the Website? – Please Support Us!

Small study, but it would explain why Gabapentin has helped so much with my pain symptoms, right?

Hi, Keira. I just wanted to ask if you’ve had an MRI to make sure that you don’t have spinal cord stenosis. … where your vertebra are becoming calcified due to inflammation and as a result becoming a narrower opening in the center. This smaller hole inside the vertebrae then can squeeze on your spinal cord and cause much much pain. I had surgery after 12 yrs of severe pain esp. in my arms and have finally gained a great portion of relief. I believe this problem with the vertebra narrowing is a common symptom with CFS/ME/FM patients but must be looked for in a deliberate manner. It has nothing to do with the discs between the vertebra that we hear most people talk about. Just a thought on my part with best wishes for you as well. marcie

Hi Keira

Although Gabapentin was originally developed to treat epilepsy its now used as a first line treatment for neuropathic pain syndromes including diabetic peripheral neuropathy which are widely believed to involve neuroinflammation. Recent research also suggests that epilepsy has a neuroinflammatory basis.

So yes theoretically Gabapentin should help although it isn’t the whole answer.

I just started Gabapentin as well. At first it was great but, the effects seem to be wearing off rather quickly. Not sure if I’m overdoing it and canceling out the benefit or if developing a tolerance to it is just the norm.

My flares coincide with elevated inflammatory markers. The big question is, what to do about it?

My flares coincide with elevated inflammatory markers. The big question is what to do about it?

I have found out in the past 3 years- I have White Matter Disease and several Infarcts.

Have had it check again with MRI and nothing has changed except my Brain is smaller. Definitely have more Cognitive problems now.

However all of mine started with Mono, Cmv, and Pesticide poisoning all within a 3 mo period.

This was at least 20 year ago.

What is the exercise for the Brain?

Aloha,

Off the top of my head (no pun intended) regarding “Exercise for the Brain”: Maybe moderate exercise and mindfulness meditation, relaxation and loving compassion, etc., for starters. While I can’t think of more in this moment, naturally, I have read other evidence based “brain” exercise if you will which are reported by some to be applicable.

I left comments below regarding CBN’s waiting for commentator approval which might be helpful as well.

Best intentions :)))

I forgot to add this “Regular exercise changes the brain to improve memory, thinking skills” – Harvard link: http://bit.ly/1ia9xOJ

Great study – great article deftly covering the issue and debate around ME and CFS. Im pleased to read this. Good evidence of neuroinflammation can only help. I dont know if others feel the same way – but I personally am glad the neuroinflammation is not as severe as a more acute encephalitis…I presume that will make it more treatable.

Thanks Steve

I’m personally hugely encouraged by this study. Role on the replications!

I agree! And they did explicitly say the findings could lead to treatments.

If this is the result of microglial cell activation there are many possibilities – although little hard evidence of what works best. Low dose naltrexone is one. I’ll be covering them in a future blog.

Doing something to reduce leptin, if that finding holds up, is another.

Spirionolactone is another – I believe it has effects as a glial attenuator (similar to LDN). It has been successfully trailed in FM with good results (published April 2014) and there are lots of animal studies out there identifying it’s role in regulating neuroinflammation.

It is really starting to feel like the puzzles pieces are falling in to place 🙂

Well spotted Chris

Is this the study?

http://www.scandinavianjournalpain.com/article/S1877-8860(14)00006-8/abstract

Hi Marco – yes that is the one. I was snooping around the net looking for further support for hypothesis that it is the anti-glial activity of LDN that brings down the volume in FM and I found this recent study.

This is great. Thanks Marco.

I was looki.g at the wikipedia site for myalgic encephalomyelitis, (which directs you straight to cfs 🙁 ), and wondering if there were any recent stidies that validate the name .m.e.

And then Marco wrote this – awesome.

Im too sick to take on any comluter projects, but it looks to me that there is enough new info with the consensus criteria and doctor primer and now this study validating fhe origi.al name M.E. for someone (Cort – kniw anyone who might be interested?:) to become a wiki contributer and make an unbiased (anti inflammatory – cool headed) page for M.E.

Xo

This study should definitely be noted on Wikipedia. It’s preliminary, for sure, – small sample size – but the Japanese authors as well as Dr. Komaroff – some pretty conservative researchers – seem pretty excited. My guess is that this study gets duplicated pretty quickly.

VanElzakker is doing a preliminary study on neuroinflammation and the vagus nerve as well 🙂

Aloha Cort, contributors and friends of this community,

Could this mean that the Israeli and other ongoing research programs usings CBN’s for neurodegeneration and reduced inflammation may be useful? Has anyone tried or does anyone use this approach? If so in what form and what have been your experiences? I’ll understand if you don’t answer 😉 I personally have not had any experience with this treatment for ME, however I am curious.

I am concerned however, that once again pharmaceutical companies will simply get away from basic fundamental nature once again and create another drug with side effects. And it makes me often wonder – if some researchers and/or companies aren’t just in the business of finding medications that create the illusion that nature should be illegal because Big Pharma has ($) government approval?

Heal and mahalos (thanks) once again for the information 🙂

P.S. I do link and “Share” to HR via my blog, FB and Twitter, etc.

Love the linking 🙂

What is CBN? I”d love to hear more about the Isreali efforts. Do you have any links by chance?

Cort,

Cbd, cbd are cannabinoids.

Long weekend. Working on some specific information (more than a link) for you that I will do my best to get out by tomorrow, busy week. No need to post this. Sorry for the delay.

Continued healing… 🙂

This research indicating the likelihood of neuroinflammation of the brain and our nervous system…. I really, really think this is going to head us in the right direction. I’ve always felt like my Central Nervous System suddenly “shorted out” one day in 1994. No matter what the initial cause, this cascade of effects on parts of the brain then go on to affect the various systems of our body.

ALSO, THE DATE FOR ME/CFS PATIENTS TO SUBMIT AN EMAIL TO THE IOM COMMITTEE IS APPROACHING… ???today??? if you want the committee to have a copy of your comments IN HAND PRIOR TO THE 2-DAY MEETING on MAY 5-6. Regardless of how you feel about the IOM, this is your opportunity to state your piece and have it placed into their hands to be read. Please remember that your statements will represent the thousands and thousands of patients who were not able to send their own so be mindful and responsible with yours. YOU can make THE difference…. you never know, for example, who contacted the Hutchinson Family Foundation asking them to investigate the issue of CFS and who got the ball rolling that created the Chronic Fatigue Initiative. Some ONE person did. Yay for them and you! marcie myers

Thanks for the reminder, Marcie.

Great article Marco. Some like you and me have been harping on about neuroinflammation and CFS for quite a few years now.

There is great promise here.

More money here, less on viruses please.

Thanks Matthias

We do tend to harp on don’t we : )

Just want to point out a typo

The estimated cost of these procedures per patient is $10,000 not $1,000 (I wish).

Sorry about that!

Ouch! $10,000! I wish that WASN’T a typo… I reluctantly fixed it.

Beautifully explained. Thank you. My morning always starts with checking Health Rising.

Talking about neuroinflammation – do you remember the proteome study on spinal fluid from CFS and Lyme patients? The Cdk5 signaling pathway, was found to be significantly enriched (p=0.00009). I have written about it: CDK5, ME and TRPA1 http://www.followmeindenmark.blogspot.dk/2014/03/cdk5-me-and-trpa1.html

And if you google neuroinflammation and cdk5 – we get further inspiration to understand what might be going on.

Very interesting blog Helle.

For a while now I’ve been considering the possibility that neuroinflammation is the common end point following a range (or combination if triggers) and as per the Dubbo findings only a small minority develop ME/CFS after common infections or complex regional pain syndrome after a peripheral injury. This suggests to me that, if neuroinflammation does play a role in ME/CFS then we must have an innate or acquired predisposition that makes neuroinflammation more likely (or more severe/chronic).

I can’t say I followed all you’ve found but if I understand correctly ME/CFS patients were found to have markers of over-expression of this Cdk5 pathway that’s linked with neurodegenerative diseases and that over-expression of Cdk5 leads to neuronal damage?

As damage to neurons activates glial cells, the neuroinflammation seen in ME/CFS may then be a protective immune reaction?

FWIW – Solme hold the view that the neuroinflammation seen in conditions such as schizophrenia and bipolar disorder is essentially the same as that leading to neurodegenerative disease such as AD or Parkinson’s – just lower level and slower. No reason why ME/CFS isn’t somewhere on this spectrum.

CFS/ME could be EBV encephalitis. But how does ecephalitis explains all other infections that have been found in CFS/ME? It make no sense to me other than the encephalitis is secondary. But this finding could be a breakthrough.

Not surprisingly, people are getting very excited about this new research that has been reported by the group in Japan who have been looking at the neurology of ME/CFS for quite some time

So am I – and I have been discussing with colleagues here in the UK how we might try to replicate these findings in another independent study using carefully selected patients

The MEA Ramsay Research Fund would be very interested in discussing if anyone wants to submit an application for funding……

But as I keep pointing out on MEA Facebook, the presence of neuroinflammation (which our post-mortem group has already reported in relation to dorsal root ganglionitis – part of the peripheral nervous system) does not necessarily mean that encephalomyelitis is present.

A lot of autoimmune and inflammatory diseases, as well as neurological diseases, have a neuroinflammatory component – but the clinical presentation and pathology is not an encephalomyelitis

Lupus for example: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0889159108000342

I continue to take the view that ME/CFS has a neuroinflammatory component

But I still don’t think that ME/CFS is going to turn out to be what neurologists and pathologists would regard as an encephalomyelitis. – i.e. extensive inflammation involving the brain and spinal cord

Abstract of our report on dirsal root ganglioitis in post-mortem cases:

Neuropathology of post-infectious chronic fatigue syndrome

Journal of the Neurological Sciences 2009 (S60-S61)

Cader S., O’Donovan D.G., Shepherd C., Chaudhuri A.

Abstract

Purpose: The pathogenesis of severe and relapsing chronic fatigue after

viral or bacterial infection is unknown. Many patients with post-infectious

chronic fatigue, which is classified as a neurological disease (G93.3,

ICD-10 classification), become disabled and do not recover fully despite

symptomatic and rehabilitative therapy.

Method: We report here the histopathological changes in the dorsal root

ganglia of three female patients with a diagnosis of chronic fatigue

syndrome. All three patients were seen by their local physicians and

specialists who had excluded alternative medical cause for their symptoms of

disabling fatigue and chronic pain. Due to the nature of death, a full

autopsy examination was carried out in each of these cases.

Results: The most remarkable and consistent abnormality was the presence of

active inflammation with T8 lymphocytic infiltration in the dorsal root

ganglion of one patient and evidence of past inflammation (nodules of

Nageotte) in two patients.

Conclusion: Dorsal root ganglion is the gateway for sensory information

reaching the central nervous system. Based on the histopathological changes

observed in three cases, we propose that inflammation of the dorsal root

ganglia may play a key role in the pathogenesis of post-infectious chronic

fatigue. Abnormal processing of sensory information secondary to dorsal root

ganglionitis could potentially contribute to fatigue due to higher perceived

effort and pain because of reduced sensory threshold. This may lead to new

treatment options in a group of patients that currently present a

significant challenge to neurologists.

Thanks for your comments Dr Shepherd – very helpful.

Also great to hear that the MEA is actively seeking to follow up on these findings.

Thanks Dr. Shepard

This is very exciting.

Really glad you guys jumped on this so quickly. I think Ramsey is probably smiling somewhere.

This

just seems so right on to me:)

Hi Dr Shepherd

I spoke to you at the Action for ME AGM about your experience or otherwise of LDN (low dose naltrexone), and I got the impression you didn’t support it as being useful then. It was mentioned several times at the 2014 IACFS/ME Conference with theoretical reasons why it may be beneficial in people with ME. Obviously I have found it useful, otherwise I wouldn’t be mentioning it, but would the ME Association encourage well conducted trials of LDN now? I know you have been active in seeking trials of rituximab, but rituximab is expensive, has significant side effects and is difficult to administer. LDN is cheap, freely available already and has a good safety profile. I wonder whether the effectiveness of rituximab will be so very different from LDN, and at significantly more cost and inconvenience to patients.

so glad their looking into the “ITIS” of this as the PRESSURE in my head for 16+yrs. is too hard to take!!! i KNOW its my brain that feels all the strange PRESSURE that i’m HITTING my head!!!

the feeling as though my head is going to explode is exactly what i’ve been feeling for TOO many years!!! i’m glad their looking more into this!!!

its IN my brain!!! its IN my brain!!! its IN my brain!!!

A few years ago, a research colleague of mine got this and called me to commiserate after his career started falling apart, complained that his head was bursting, that he was so weak his little sister could beat him up. Another one bit the dust I’m afraid.

When you consider the fact that millions of people around the world have this condition, with its attendant loss in productivity and increase in misery, I would think that spending a few grand for some studies is well worth it. Arigato gozimasu, Japan, and keep it up!

For what it’s worth, that is precisely what “brain fog” feels like to me: neuroinflammation.

I was going to say that as well…I’m not sure what neuroinflammation feels like, but my guess is that it feels something like ME/CFS.

Radio interview with neurologist Dr Abhijit Chaudhuri – who is also a member of our post-mortem tissue research group:

Inflammation in Chronic Fatigue

Dr. Abhijit Chaudhuri, Queen’s Hospital, Romford and Professor Hugh Perry, Southampton University

Louise –

Think back to the last time you had the flu. You probably had some muscle pain and a bad headache, felt completely exhausted, and you might even have had trouble thinking straight. Most people get over the flu and other viral infections including glandular fever in a few weeks or so. But for a few people, those symptoms continue for months and years afterwards, becoming chronic fatigue syndrome. Not everyone with chronic fatigue syndrome has a viral infection before they develop the disease, but many patients do, and it is often the flu or glandular fever.

And although chronic fatigue syndrome was first defined in 1988, we still don’t know how, or why, these viral infections seem to be able to trigger the condition. And in fact, we have very little idea of what’s happening in patients’ bodies to cause their symptoms.

Post mortem studies are one of the best places to start. Now, a team including Dr. Dominic O’Donovan from Addenbrooke’s Hospital in Cambridge and Dr. Abhijit Chaudhuri from Queen’s Hospital in Romford has looked at the nervous systems of four patients who suffered from chronic fatigue syndrome.

Here’s what Dr. Chaudhuri has to say.

Thanks

This

“So, all the chronic fatigue patients included in this study had either active inflammation in their peripheral nervous system or signs of a degenerative process in their spinal cord and brain.”

is so enticing. I wonder if anyone anywhere is doing more autopsy studies. Even though it was only four patients the results look pretty prescient today, at least.

The Broderick team at NSU, by the way, is modeling neuroinflammation in ME/CFS – looking for evidence of stable neuroinflammatory states.

I’ve been wondering for a while why autopsy studies on the nervous system of ME/CFS patients does not seem to be a key area of research. I would have thought it would be one of the first places to go and look for evidence of abnormalities. Also why can’t samples of these tissues be used by researchers such as Dr. Lipkin and Montoya to look for pathogens? I know they said, obviously, brain biopsies from live patients are hard to come by, but surely there are enough from autopsies. I plan to leave my body ( hopefully not soon), including my brain, to ME/CFS research. Is there a place where nervous system tissue can be sent? Do we need to start a brain bank? Professional athletes are now donating their brains somewhere for research on concussions.

Claire – if you live in the UK we have an ME Association ‘statement of intent’ form that can be added to your Will to make it clear that you want to donate tissue to post-mortem research into ME/CFS that forms part of this on-going study.

We have also published (Journal of Clinical Pathology, 2010, 63, 1256 – 1265) plans to set up a proper ‘bricks and mortar’ brain and tissue bank here in the UK – but this type of infrastructure requires a large amount of money to set up and sustain.

I’m afraid our post-mortem tissue group cannot accept post-mortem tissue from overseas at present – I attempted to do so a couple of years ago and the legal/ethical/administrative problems were so enormous that I gave up in the end.

Abstract from JCP paper:

J Clin Pathol. 2010 Nov;63(11):1032-4. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2010.082032. Epub 2010 Oct 5.

Exploring the feasibility of establishing a disease-specific post-mortem tissue bank in the UK: a case study in ME/CFS.

Lacerda EM1, Nacul L, Pheby D, Shepherd C, Spencer P.

Author information

Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS) is a condition, the aetiology of which remains controversial, and there is still no consensus on its nature and determination. It has rarely been studied in post-mortem examinations, despite increasing evidence of abnormalities from neuroimaging studies.

AIM:

To ascertain the feasibility of developing a national post-mortem ME/CFS tissue bank in the UK, to enhance studies on aetiology and pathogenesis, including cell and tissue abnormalities associated with the condition.

METHODS:

The case study was carried out combining qualitative methods, ie, key informant interviews, focus group discussions with people with ME/CFS, and a workshop with experts in ME/CFS or in tissue banking.

RESULTS AND CONCLUSIONS:

The study results suggest that the establishment of the post-mortem ME/CFS tissue bank is both desirable and feasible, and would be acceptable to the possible tissue donors, provided that some issues were explicitly addressed.

I live in Canada but actually am a British Citizen and have a British passport. I’m not sure if my passport would still be valid for my body parts once I am dead (sorry, sick sense of humour).

I used to work, and actually still hold a position, in the Pathology Lab at the Ottawa Hospital in Ottawa Canada. We keep years and years worth of body parts from all autopsies done and decades worth of slides, all for medical-legal issues, as I’m sure all hospital laboratories do. Unfortunately so many (perhaps all?) people that pass away who had ME/CFS usually don’t have that on their death certificate or even on their hospital admission forms since we generally keep that quiet due to biased and poor treatment as a hypochondriac, neurotic or other type of psychiatric patient.

I think it was Dr. Lipkin and/or Dr. Chia mentioning that they can’t study cardiac tissue for presence of viruses because there just isn’t cardiac tissue being taken out of live patients, yet here at the Ottawa Hospital which is affiliated with The Ottawa Heart Institute, we have multiple cardiac biopsies, cardiac valves and other pieces of cardiac tissue daily pass through the lab and preserved for eternity in formalin. It would be great to access these from patients with CFS. If only I had the energy and money……..

Here in the UK, when we have gone through all the complicated and time-consuming legal, ethical and practical procedures that are necessary in order to obtain post-mortem tissues for research purposes we are are looking at other tissues besides the central (brain) and peripheral nervous system. So we also obtain, whenever possible, some skeletal muscle, cardiac muscle, intestinal wall and innervation, and adrenal glands.

One of the major practical problems we face is that for certain procedures that are being carried out on the tissues obtained they have to be removed, fixed/frozen and suitably stored as as soon as possible following death – preferably within 48 hours. If not, vital information/evidence on what is happening regarding viral material and biochemical reactions in tissues disappears very quickly. So this means obtaining all the necessary permission and co-operation to go ahead with all involved (relatives, pathologists, coroners etc) in a very short period of time.

You also need a a good neuropathologist who is keen to do this research work in relation to ME/CFS – which we fortunately have here in the UK.

Marco,

Fine piece of informative writing. Congrats.

So they found neuroinflamation in the brain, but no significant evidence of it in the peripheral system? What kind of causative factors would that implicate or eliminate? Here I’m wondering about certain type of viruses, bacteria that don’t/do cross the blood/brain barrier. etc. how about autoimmune diseases..?

Are the glial cells thought to be the source of the inflamation or is the source pretty much unknown?

Thanks Tim – it was nice to write a relatively straightforward piece for a change.

Good questions and ones I’ve been pondering myself lately.

Firstly they were specifically (and could only using this approach) looking at the brain so can say nothing about peripheral inflammation. So we can only speculate as to where the CNS neuroinflammation is coming from.

The usual view of ‘encephalitis’ (which as has been stated this isn’t evidence of) is that a neurotropic (neuron targeting) infection (viral, bacterial) manages to ‘get past’ the blood brain barrier causing infection/damage to the brain. As far as I’m aware though no single neurotropic infection has been found in ME/CFS.

The idea though that the brain is ‘immune privileged’ (ie protected from peripheral infection/immune response) has now been moderated and its now believed that this privileged status is conditional – not only do we have peripheral immune/brain ‘crosstalk’ but the blood brain barrier can be temporarily compromised – as in the case of a peripheral nerve injury where pro-inflammatory cytokines do just that (as per my earlier blog on complex regional pain syndrome. ‘Gliatropic infections are another possibility. They don’t need to cross the BBB they can reach the brain via ‘spreading neuroinflammation.

As Dr Shepherd stated blog and as I state in the blog neuroinflammation is associated with a wide range of conditions including neuropathic pain; autoimmune; psychiatric; diabetes; normal aging and stress.

Which might seem as if it doesn’t get us any closer to the answer – after all if its so ‘non-specific’ how does this help? I take the opposite view. If neuroinflammation is key to the range of symptoms found in ME/CFS and it can have a wide range of triggers then it could explain both the heterogeneity of symptoms and types of onset seen in ME/CFS plus the fact that no single infection has been linked to it – its seems that again a wide range of infections can trigger it.

Neuroinflammation in the elderly is interesting (several finding such as reduced telomere length and reduced antioxidant capacity overlap in normal aging and ME/CFS). It appears that microglia are ‘primed’ in the elderly with the effect that even common infections easily provoke microglial activation and an exaggerated ‘sickness response’. Which may explain why the elderly can often experience such a sudden decline in health following normally ‘trivial’ infections or accidents.

I suspect the ‘flu from hell’ that many ME/CFS patients report at onset might suggest that a certain degree or ‘glial priming’ may have preceded the infection.

Finally (at last : ) ) autoimmunity might fit in nicely with a ‘multi-hit’ scenario. As has been hypothesised for complex regional pain syndrome, anything that causes the release of peripheral pro-inflammatory cytokines has the potential to temporarily disrupt the blood brain barrier potentially allowing for the infiltration of autoantigens to the brain.

All speculative of course.

Edited to add – basically what I’m saying is that neuroinflammation does not require infection and can be triggered by a range of peripheral ‘insults’ including peripheral systemic inflammation :

Peripheral inflammation in neurodegeneration.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23546523

The idea that CFS is caused by various random stimuli does not fit with the widespread pattern we see where millions of people present with a remarkable commonality of symptoms. That’s not to say that everyone has exactly the same symptoms, but somehow this seems like something caused by some sort of pathogen, especially since the disease has flu-like characteristics. Maybe the German research into EBV will be key.

At least with the Japanese pet study, and now with the autopsies, we are finally getting proof instead of speculation.

Dr. Komaroff mentioned in his Stanford conference summary that pathogens have not been found “in serum”, that no investigations have been carried out yet for white cells or nervous tissue pathogens. It sounds like they are being undertaken now. I look forward to more tangible findings from those efforts in the near future.

Hi David

I’m not ruling out the possibility that one pathogen underlying ME/CFS will be found but it doesn’t seem necessary (or sufficient) to develop ME/CFS (the Dubbo studies strongly suggest that several common infections can trigger ME/CFS in a small minority of patients while some folks like me didn’t have a noticeable viral onset). Plus the repeated failure over many years to find a single pathogen makes this scenario (for me) less likely.

The commonality of symptoms is a rather circular argument to make in a condition that can only be diagnosed on the basis of symptoms – if we didn’t have a similar collection of symptoms we would probably have another diagnosis.

it is not really new or surprising at all.

when you look at the study of air pollution(pm2.5)–there are hundreds of research papers

about neuro inflammation from air pollution–including TNF-ALFA,IL-1BETA AND IL-6

At present time, the polluted air all over the world.

is the direct cause of CFS/ME.

MARCO , CORT , BLOGGERS ESTE IMPORTANTE ESTUDIO NO EXPLICA LA OTRA GRAN CANTIDAD DE SÍNTOMAS Y ALTERACIONES PRESENTES EN ME COMO DOLORES ARTICULARES TIPO REUMÁTICO , TUMORES TIROIDEOS , NK , LINFOCITOS T Y B ALTERADOS , PROBABLE DISMIELINIZACION DE NERVIOS PERIFÉRICOS , DESTRUCCIÓN DESISTEMA NERVIOSO AUTÓNOMO Y OTROS . ME FCS PUEDE SER EXPLICADA , AL MENOS EN TEORÍA Y SER INCLUIDA EN LA CATEGORÍA DE ENFERMEDAD AUTO-INFLAMATORIA POLIGENICA Y POR LO TANTO LOS ESTUDIOS Y TRATAMIENTOS DIRIGIDOS A SU CURACIÓN DEBERIAN DE INCLUIR LA ANTERIOR HIPÓTESIS .

ATTE. DR FCO VICTORIA PRESIDENTE DE FIBROAMIGOS MÉXICO

From Google Translate : MARCO, CORT, BLOGGERS THIS IMPORTANT STUDY EXPLAINS NO OTHER LOT OF THESE SYMPTOMS AND CHANGES IN ME AS JOINT PAIN rheumatic, THYROID TUMORS, NK lymphocytes TYB ALTERED, PROBABLE dysmyelination PERIPHERAL NERVE, SELF DESTRUCTION AND OTHER NERVOUS DESISTEMA. FCS ME BE EXPLAINED AT LEAST IN THEORY AND BE INCLUDED IN THE CATEGORY OF AUTO-INFLAMMATORY DISEASE polygenic AND THEREFORE DIRECTED STUDIES AND HIS HEALING TREATMENTS SHOULD INCLUDE THE ABOVE SCENARIO.

ATTE. FCO VICTORIA DR MEXICO PRESIDENT FIBROAMIGOS

From Google Translate: Gracias por el comentario interesante. ¿Qué tan bien es la fibromialgia o síndrome de fatiga crónica se conoce en México?

Thanks for the informative article. My experience with this illness has always led me to believe neuroinflammation played a prominent role. I have consistently described a burning pain from mid-spine up to the base of my skull to the doctors who I have seen. I had several epidural injections that were of little benefit, and successful surgery for stenosis at three levels in my cervical spine.

Another element in my situation that initially complicated the picture further was the discovery of a benign cyst in my left temporal lobe. Based on unusual sleep problems that sleep doctor/neurologists thought might be seizures, they conducted EEG monitoring in a sleep lab. While a seizure did not occur during the lab (how typical) there were several periods where I set off the monitoring system due to shifts in brainwave activity associated with the cyst in my temporal lobe. I was first put on gabapentin, and when I found it unsuitable, I was switched to another anti-seizure med called Topamax which is also commonly used for migraines. For me, the Topamax was a far better option.

While I had difficulty believing at first the Drs’ opinion that the cyst had always been present, after years of seeing the same picture on the MRI, I grew to accept it. Now I believe that while it was always present, it simply became a focal point for the inflammatory activity that began when ME/CFS entered the picture.

All of this being considered, I think it is still important to remember to see this as a partial description of a larger picture that emanates from an immune-mitochondrial dysfunction that allows pathogens to escape elimination.

This :

http://www.clinicalpsychiatrynews.com/news/adult-psychiatry/single-article/video-link-found-between-neuroinflammation-and-suicide-attempts/ba3487ee8f6342e297379162a2a5970b.html

Suggests that some metabolites of neuroinflammation (via the TRYCAT pathway) may be detectable in the blood (which may also be linked to mood/behavioural consequences of neuroinflammation).

“In a study of 100 people who attempted suicide, researchers found the persons all had elevated levels of proinflammatory cytokines in their blood, according to a presentation made at this year’s annual conference of the Anxiety and Depression Association of America.”

“In an interview, Dr. Brundin explains her hypothesis for the mechanisms of this neuroinflammatory response: that metabolites in the kynurenine pathway adversely affect glutamate neurotransmission (kynurenic acid is an antagonist of the glutamatergic N-methyl-D-aspartate [NMDA] receptor), creating “very profound and strong effects” on the brain, and possibly contributing to suicidal ideation.”

Edited to add :

These markers of neuroinflammation may have already been found in fibromyalgia patients as Cort blogged some time ago :

http://www.prohealth.com/library/showarticle.cfm?libid=18347

how about this drug for reducing microglial activation:

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23518709