(Julie Rehmeyer has experienced the ups and downs of Chronic Fatigue like few have. After years of gradual deterioration her health took an enormous and mysterious dive when she awoke one morning in 2006 barely able to walk. Six years later after work with an ME/CFS specialist failed to provide much help Julie tried mold avoidance. A month in Death Valley appeared to accomplish little but a strict mold avoidance protocol afterwards worked and over the next two years she slowly recovered a substantial amount of her health. Julie still has limitations and must be careful about mold but is now able to exercise and run, travel and work full time. She is currently working on a book about her experiences and the politics and science of ME/CFS. )

Julie’s Story

How long ago do you think your ME/CFS began?

My health began deteriorating in 1999, but it didn’t turn into full-blown, CCC-style ME until 2006.

(Julie woke up one morning in 2006 barely able to walk (see below). See Julies blog here for more on her Chronic Fatigue Syndrome story)

Were you able to track back your gradual onset or your sudden collapse to any exposure to mold?

I first started getting CFS when I was living in travel trailers while I built my house, and I now know they were moldy (like pretty much all old travel trailers) though that wasn’t obvious at the time. I moved to Berkeley in 2006, and Berkeley is notorious among those who are hypersensitive to mold for having some kind of widespread outdoor toxin that makes us really sick. My illness began progressing to the point where something was clearly really wrong around the time I moved.

My full-on collapse came at the end of 2006, when I was living in DC (which probably has a similar outdoor toxin) and had just gotten a hepatitis-A vaccine. I think the vaccine was the last straw, rather than a major cause in itself; I was generally deteriorating over the previous months.

Your story reminds me of Joey Tuan’s – he tried EVERYTHING before he tried mold avoidance – and then it worked (lol). You’d been to see one of our best – Dr. Klimas – without getting really good results.You’d probably experienced the best traditional medicine had to offer yet you still had trouble walking and your health was still poor. Was it only after that didn’t work out that you felt like turning to something like mold avoidance.

Oh yeah, absolutely. Mold avoidance sounded pretty kooky to me — until it worked. And Joey was a huge inspiration to me! His blog post about how he could exercise again was one of the things that made me consider mold avoidance in the first place.

Did a doctor advise you on mold avoidance or did you do it yourself?

I primarily relied on the help of other patients.

I wrote a story for Slate about ME/CFS in late 2011 while I was terribly, terribly ill — it was a tiny window when I was barely capable of it, and writing it left me barely able to make it from bed to the bathroom for a week after I finished it. But as a result of it, I was contacted by a fellow patient who is also nearly recovered through mold avoidance. Around the same time, my primary care doc mentioned the possibility to me that mold was contributing to my illness, and he gave me Shoemaker’s “Surviving Mold.”

I found the book nearly unreadable, though, and I probably wouldn’t have pursued it further (certainly not in the intense manner necessary) without this person’s help. That’s especially true because I was initially skeptical that mold could have anything to do with why I was sick: I’d gotten sick while living in dry New Mexico, I’d never lived in an obviously moldy building, I’d lived in many different houses during the time I’d been sick and I’d never gotten dramatically worse after moving, I’d never suddenly felt much worse when I walked into a building. It just didn’t sound like me at all.

She explained that I might not be reacting noticeably because my belongings could have gotten contaminated — particularly likely since I’d lived in Berkeley, which is so notoriously bad for folks who are sensitive to mold — and if that were true, I would be so steeped in it that I would never notice any variation. She suggested that a way to figure out if mold was contributing to my illness was to get clear of it by going to a particularly pristine desert for two weeks with none of my own belongings. The critical thing wasn’t whether I felt better while I was there — that might or might not happen, she said — but to see if I reacted to my own living space when I got back. If I did, then mold was almost certainly contributing.

Lacking any better ideas and figuring that if I had to have this damn disease I could at least have an adventure, I decided to try it. I seized a moment when I thought I was just well enough to do it, borrowed a bunch of stuff and swapped cars with a friend (hoping his stuff wasn’t problematically moldy), bought some new stuff, and went to Death Valley.

Treatment

Extreme avoidance is a very challenging path. Some people are too sick to do it at all, and it’s especially difficult if you have kids or a partner who isn’t amazingly accommodating, flexible and supportive. Frankly, it’s a lousy solution — but compared to no solution, it’s pretty darn great.

The Death Valley trip was just the beginning. Two years of mold avoidance awaited Julie when she got back.

While I was in Death Valley, I felt slightly better, but well within the range of normal variability. Before I went home, I went to Reno to visit Erik Johnson, the “mold warrior” who was one of the famous Tahoe cohort and who was the first ME patient to figure out the role of mold in his illness. He took me to some bad buildings around Lake Tahoe to help me learn the early symptoms of exposure.

I was extremely skeptical at that point, not being at all sure that this theory applied to me, and I was even more skeptical when I didn’t seem to feel much in the bad places he took me to. But indeed, a few hours after my “mold tour,” I could barely walk (a symptom I hadn’t been having much at that particular period). That was the first indication that I was hypersensitive to mold. I was very excited and fired off emails to friends: “Woohoo! I can’t walk!”

Then I went home to New Mexico, which I’d moved back to from Berkeley. My house was rented out and I was living in those same travel trailers I’d been in when I first started to get sick. Thirty seconds in my trailers was enough that I could barely walk a a few hours later. I also had more immediate symptoms that weren’t quite as acute.

Learning to recognize subtle symptoms of exposure is really critical. I found that after a while of practicing avoidance, I had no trouble at all recognizing when I was exposed because my reactions became quite strong, but early on, they were subtle and easy to miss.

What kind of mold avoidance did you do?

The critical thing wasn’t whether I felt better while I was there — that might or might not happen, she said — but to see if I reacted to my own living space when I got back. If I did, then mold was almost certainly contributing.

Extreme. When I got back from Death Valley, I found that I reacted strongly not just to the trailers but to my belongings in the trailers. I got rid of nearly everything that had been in Berkeley or the trailers. Luckily, the person renting my house at the time happened to break her lease and move out, so I was able to move back into my house, with just my camping gear.

Even more luckily, my house turned out to be mold-free and in a location with good outdoor air. The hardest part of avoidance for many people is that they have enormous problems finding a house they can live in. And if instead of living in my trailers when I returned from Berkeley, I’d moved back into my house with all my Berkeley-contaminated stuff, it might have made it unworkable for me for years. So I was hugely blessed.

After I moved into my house, I was extremely careful to keep my house good for me. I washed my clothes and showered as soon as I got home after going out, and I was vigilant in preventing contaminated objects from coming in. Over the next year, my reactivity got crazily extreme, to the point that once when I was stuck in a moldy tow truck, I went into convulsions. After a year, the reactivity went down, and while I still react, it’s not extreme or frightening anymore, just unpleasant.

Did you do any tests for mold and if so what were the results?

Yes, I did Shoemaker’s tests, which showed the typical pattern of inflammation for mold-injured people. They also showed that I’m genetically susceptible to mold. I didn’t test any buildings for mold — my own reactions were proof enough for me.

How long did it take you to see results?

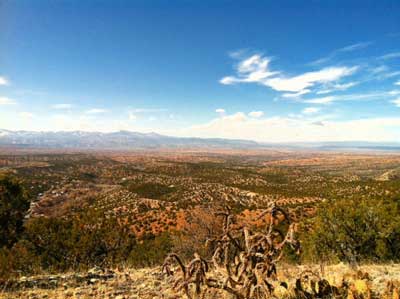

Julie’s ability to hike to this outlook a month or so after she’d returned from Death Valley indicated she’d improved dramatically

A month after heading to Death Valley, I was able to hike up the hill behind my house, which is a 300-foot climb. I hadn’t been able to do that in about a year and a half. I was astonished and overwhelmed, and I emailed a zillion people from the top of that hill with a picture of the incredible view from there across the Rio Grande Valley, saying, “Oh. My. God.” That was the first indication that this whole crazy mold thing was actually going to make me better.

Over the last two years, I’ve done a lot of detox, and that’s been an important part of getting stronger and more resilient. Unfortunately, detox also tends to make you feel crappy in the short term, so I continued to deal with quite a bit of crappiness thereafter. But essentially, I was very much better very quickly after returning from Death Valley.

Do you have any idea what’s going on with Berkeley? Is it because it’s near the ocean do you think?

I don’t think being near the ocean is the key. Some locations near the ocean are excellent — I felt terrific in Hawaii, for example, and San Diego is reasonably OK for me. Many ME patients report doing well on tropical islands. But I really don’t know what is going on.

Do you need to continue with mold avoidance and if so what do you do?

Absolutely. I can detect when I’m in a moldy building very quickly now, and if it’s at all bad, I get the hell out of there. And I continue to be careful to keep my home toxin-free. It was extremely consuming for quite a while — it takes an enormous amount of effort to learn to detect mold quickly, to be sufficiently careful about protocols to keep your home and belongings free of mold, and to ferret out the problem when somehow your house does get contaminated (which is close to inevitable from time to time). I didn’t do much work for nine months after starting avoidance because it was so demanding. It’s no longer nearly so difficult now, partly because I’m better at it and partly because my reactivity is so much lower that I don’t need to be nearly as careful.

How important is getting the mold out of your clothes? I guess the idea is that you’re become hypersensitive to even very, very small amounts of mold and getting that out of clothes, off your hair, etc. becomes very important when you become hypersensitive?

It’s very important to have mold-free belongings, and yes, when you’re hypersensitive you react to almost unbelievably small quantities of contaminants, and those tiny quantities can be enough to keep you sick. I didn’t even try to save the clothes or other belongings from Berkeley, and I’m glad I didn’t. One thing I did try to save was a winter coat that I left outside under a carport for nearly a year, and at the end of that time, even after having it cleaned, it still bothered me. Of course, it’s possible that some of my belongings could have been saved, but the amount of trouble that can come from a single contaminated item is enormous, and I felt like it wasn’t worth it. Pretty much all that I saved were glass and metal objects, which I cleaned carefully and didn’t have any problem with.

Others

“To me, the main thing to be taken from the success of extreme avoidance for some people is that we need some serious research into the impact of mold and related contaminants in ME/CFS and more generally.”

Did you ever have chemical sensitivities?

Not really. I had a great deal of difficulty finding a bed I could tolerate, and that may have been because of fire retardants or other chemicals in them. I just don’t know. But in general, no. Many people do develop chemical sensitivities in the process of avoidance, but it seems like it’s generally less critical for them to avoid every chemical that bothers them than it is to avoid mold — and especially to avoid the mysterious outdoor contaminant in Berkeley and other places, which seems to be remarkably bad for us.

Do you become sensitive to molds found out in nature or is it usually to molds found in the house? I remember taking a close look at a Joshua Tree and I was surprised to see how much mold was present even in that desert environment. Could something like that be bothersome?

I think that would be unlikely to be a problem for me personally, though people vary in these things. I also don’t have trouble with food molds, though I think I’m in the minority on that among those who are hypersensitive.

It’s clear that species of molds vary enormously in how problematic they are. And the problem may well not just be the mold itself — it may be the mycotoxins molds produce when they go to war with one another, or the volatile organic compounds they release, or the mycotoxins or VOCs that they produce only when they’re eating some particular substance. (I wrote an article about this here.) It’s all, unfortunately, quite complex.

At the moment, the best resources about mold and mold avoidance are paradigmchange.me and the Facebook group “Avoiding Mold.” I have to caution, though, that extreme avoidance is a very challenging path. Some people are too sick to do it at all, and it’s especially difficult if you have kids or a partner who isn’t amazingly accommodating, flexible and supportive. Frankly, it’s a lousy solution — but compared to no solution, it’s pretty darn great.

I think it’s important to understand, though, that extreme avoidance is more valuable as a clue than as an answer. We need to know how big a role mold is playing for ME patients in general, not just the few who have tried extreme avoidance. And even if it turns out that mold is a major player for everyone (which we certainly don’t know now), we can’t possibly have a million people in the US doing this. We need something better. To me, the main thing to be taken from the success of extreme avoidance for some people is that we need some serious research into the impact of mold and related contaminants in ME/CFS and more generally.

The book I am writing will describe my experiences in much greater detail, and it will weave in a lot of information about the science and politics of mold, ME/CFS, and other confusing illnesses.

As you avoided mold more and more you found that you felt worse and your sensitivity to mold went up greatly. Did you experience times of increased health interspersed with these really strong reactions? Is this a common pattern?

Yes. As long as I successfully avoided it, my health was much improved. And yes, that’s a common pattern. The reactions typically were short-lived — showering, changing clothes, perhaps doing some additional detox would generally take care of it, as long as I was pretty quick about getting out of a bad place. Early on, when I wasn’t so good at recognizing mold, I would often feel lousy for a full day, because I’d gotten too big a dose.

Is there anything specific you do to detox? Take supplements? Sauna? Or is it more a matter of making sure that you’re not in contact with mold?

I take a bunch of supplements that are supposed to support liver function, though I’m not confident that they’ve done much for me. Many people find cholestyramine helpful, though I personally didn’t. The things that have been most useful for me are far infrared saunas and, especially, coffee enemas (which sound awful, but man oh man, they make me feel better). Exercise can be helpful too, if you can do it.

On a scale of 1-10 with ten being perfect health where would you say you are now?

Maybe 8.5, but words can convey more than numbers. I’m working pretty much full-time, and I’m living quite a rich and full life. I travel with my husband quite a lot, I’m writing, I socialize, I can exercise, and probably most people who know me don’t ever see any signs that I’m not 100% well. However, I typically wake up in the morning feeling lousy, and I have to detox to get functional (though that seems to be lessening a bit). I occasionally lose a day to feeling bad, and I can’t always figure out why, though I often can trace it to some exposure that I didn’t manage to deal with quickly or thoroughly enough.

I couldn’t do a regular 8-5 office job; the flexibility of my work is key. I can sometimes exercise quite a lot and other times not much; I have to pay careful attention to where my body is day-by-day. And I certainly couldn’t live in Berkeley or many other places. I visited Berkeley recently, and I was amazed at how strongly I reacted to the outside air there: It felt like my entire nervous system was being crushed, and after a while I found it quite difficult to speak. But I was pleased to find that I could visit Berkeley for an hour or two at a time (decontaminating afterwards) without lasting problems.

I still sometimes get very impatient with the process, wanting to not have to worry about this crap anymore and just be well! Overall, it feels a little bit like having a toddler — a toddler’s needs come first, but you can bring a toddler along with you to lots and lots of things if you really want to. Actually, I guess things are a bit better than that now, and maybe it’s more like having a five-year-old. Not quite so demanding anymore. And I’m hopeful that with more time and detox, I’ll get significantly better still.

Lisa has a new blog post with just about everything she knows or suspects about this phenomenon. Much of it is speculative, of course, since there’s no formal research on the subject. But that post I think provides a useful place to start in trying to understand it.

Double Black Diamond Topic

You’re an accomplished writer and you clearly did a lot of work on the blogs yet they ended up on a small blogging site on the internet – not in a major publication. They certainly read like they should be in magazine somewhere. How did they not end up in one?

Yeah, I worked like hell on this piece. It went through at least a dozen drafts, with substantial changes between the drafts, and I started it last November. I don’t even know how many people I talked to about it — well over a dozen, maybe two dozen. I wrote it hoping to get it in a very prominent publication (the name of which I won’t mention), and they held it for two months, deliberating, and then said no. I tried a few more publications and got no bites, and I got to the point where I was just exhausted and felt like one way or another, it needed to get out there.

The reality is also just so different from what people tend to imagine before they read about it that they can’t quite believe that what I’m saying is true. The narrative that’s in everyone’s minds is that it’s so, so controversial whether this is a real illness, and when I say that actually, among experts in the US, that’s not controversial at all, it doesn’t seem very plausible. All of that is frustrating, but it’s just the way things are.

I ran it in Last Word On Nothing because the site is run by friends of mine, and although its readership isn’t all that big, it includes a lot of science writers, and they’re some of the folks I’d most like to influence. Even in the top science magazines, the quality of journalism about ME/CFS isn’t what I wish it were, because it’s a really hard subject to parachute into as a journalist. The history is complicated and deep and affects everything, and the science is complex and messy and confusing, and just figuring out who the players really are is tough. And then even if you manage to figure all of that out, presenting all that complexity in a linear story readers will be interested in and absorb is another challenge, along with understanding the needs and sensitivities of the various stakeholders so that you don’t inadvertently say something you think is harmless that will infuriate someone. So part of what I hoped to accomplish with the piece was to give science journalists a bit of background, so that they don’t start out cold the next time they find themselves covering something about the illness.

Honestly, this is the hardest piece I’ve ever written. I often write about math, which Carl Zimmer called the “black diamond trial” of science writing, but math is nothing compared to writing about ME/CFS. It’s also immensely satisfying, though, because it really matters. And it has a big impact on me to write about it — it helps me understand what’s going on better, it helps me to integrate and make sense of my experiences, it helps me connect my own experience with that of others and feel less alone. So as much as I would have loved to have this in a big publication, I’m still really glad I wrote it, and I look forward to doing more pieces over time. (Not right away though! I need to make some money and work on my book.)

And maybe I’ll even manage to break into that prominent pub that held my piece for two months. I haven’t given up trying.

Julie’s Blogs

- Why Are Doctors Skeptical & Unhelpful about Chronic Fatigue Syndrome? Pt I

- Why Are Doctors Skeptical & Unhelpful about Chronic Fatigue Syndrome Pt. II

Julie Rehmeyer is a math and science writer in Santa Fe, NM. She is a contributing editor for Discover Magazine and has written for Science News, Wired, Slate, Science, and other publications. She is working on a book about her experience with ME/CFS and the science and politics of confusing illnesses. She recently wrote about her father for Aeon

How does one know where to go?

Can you rent a trailer in Death Valley or where do you stay?

Is two weeks enough?

(I’m from the Netherlands)

Thank you so much for bringing your article to Cort’s website … and thank you to Cort for publishing it here. Wonderful, concise writing … remarkable results.

You know what I love in an interview? Complete answers! Thanks to Julie for her generosity in thoroughly responding to the questions 🙂

Were you ever allergy tested for molds?

I was, and molds weren’t an issue. This is a toxic effect, not an allergic one.

This story is an example of how different conditions can be diagnosed as Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. Julie discovered that mold was the culprit in her downward health spiral but for others it may be something entirely different or a combination of causes. My personal understanding of CFS is that it caused be an accumulation of physical stress for which a person can no longer compensate. Recovery is therefore unique for each individual.

I was pondering the same Question as Esme before coming back on to post. Does anyone know if there is a place considered to be the Mold Free Capital of the World, or the US? I had the same thought, which was to find that place and find a way to stay there for a week or two and see what happens. Is it death Valley (sounds appealing seeing as Im so ill I feel like dyin!)?

If anyone has some thoughts on how to find a mold free spot for a couple of weeks please share them.

Thank you!

My apologies, In my Fogged State I missed the paragraph in the story about the reasoning for the Death Valley venture.

Something came to mind while reading this blog. Before I was so ill that I had to stop working, over 20 years ago, I worked with Albert Robbins, DO, an Environmental Medicine Specialist, in Boca Raton, FL. He has a large practice, used many “unorthodox” treatments; ran a support group that met on the beach. He also ran a motel located near the ocean that had only iron furniture, and natural cotton fabrics. I had completely eliminated mold from my home, so I didn’t feel it necessary to avail myself of that facility. But, as I remember, people came from all over the US to live there for a bit so their bodies would have a chance to “take a break” from chemicals and mold. I remember ordering a cookbook from one of these people and when it arrived in the mail she’d written a note saying “we are like the canaries miners used to use to make certain the air was OK”. I stopped seeing him after only a year of treatment because his protocol caused me to be even more fatigued…exhausted, and it wasn’t covered by my insurance and I could not afford to pay for it myself.

Dr. Robbins did help people whom I know; he suddenly retired after my first visit to him about two years ago. I do not know if he is still with us. As Darden stated in the comments above, everyone is genetically and biochemically unique, so not all approaches will work for everyone. Also, “traditional” medicine might be more accurately called “conventional modern,” because “traditional medicine” is a term co-opted from indigenous or ancient cultures who have provided us with knowledge of plant and mineral substances which heal (i.e., TCM, Traditional Chinese Medicine). Conventional modern big pharma has made billions from altering natural substances and patenting them and provided some symptom-relief band-aids but little in the way of real cures. Many have been helped some, and yet it is said that hundreds of thousands have died from drug toxic side effects in just a few years in the U.S. alone (have to double-check stats on that). There may be a possibility during the current paradigm shift that new advances in the neuroscience/natural medicine marriage may be able to reset our complex body/mind systems and keep the immune system from hyper-reactions to mold and chemicals. Even so, Environmental Integrative Medicine and mold-free nontoxic housing should be international medical priorities made affordable for those who need these. This can happen over time as people demand it in greater numbers and more effective activism.

another great article, series of articles.

Environmental Intergrtive Medicine is my path, very expensive, but what wouldn’t you pay to get out of this existence. i think we wold all spend what we could for’no harm’ options. Most costs are met by an insurer as my onset was after a chemical exposure at work. so unlucky, but lucky really.

Hyperthermia treatment (extreme far infrahred treatment) I beleive has kick started my immune system, aside from the detox component. 5 months in, I have only one session every three weeks and receive vit c, iv magnesium and oxygen.

Even though I am undergoing chelation treatment for heavy metals I am noticing improvement. Times of mental clarity. I can remember my car registrtion plate and operate the blinds in my bathroom. after two and half years of severe illness these steps are huge to me.

I have been reading Dr Bruce Lipton articles, and he too was scoffed at, but epigenetics is now showing he was right, battle on Julie, you have my support 🙂

Does moving to a lower altitude work? Or do you acclimate? Julie did that happen to you when you tried out Death Valley?

I don’t think the lower altitude was the essential element. You do acclimate fairly quickly.

About toxins.

Recently I’ve seen a connection being made between C. perfringens toxin — (Clostridium perfringens) — and muliple sclerosis.

I thought it was interesting that, on the one hand although it’s secreting a toxin, on the other hand it’s a bacillus and not mold (fungus).

Here’s an abstract. The full article if available a Public Library of Science (PLOS) if anyone wants it.

PLoS One. 2013 Oct 16;8(10):e76359. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0076359. eCollection 2013.

Isolation of Clostridium perfringens type B in an individual at first clinical presentation of multiple sclerosis provides clues for environmental triggers of the disease.

Rumah KR1, et al.

Abstract

We have isolated Clostridium perfringens type B, an epsilon toxin-secreting bacillus, from a young woman at clinical presentation of Multiple Sclerosis (MS) with actively enhancing lesions on brain MRI. This finding represents the first time that C. perfringens type B has been detected in a human.

Epsilon toxin’s tropism for the blood-brain barrier (BBB) and binding to oligodendrocytes/myelin makes it a provocative candidate for nascent lesion formation in MS.

We examined a well-characterized population of MS patients and healthy controls for carriage of C. perfringens toxinotypes in the gastrointestinal tract.

The human commensal Clostridium perfringens type A was present in approximately 50% of healthy human controls compared to only 23% in MS patients.

We examined sera and CSF obtained from two tissue banks and found that immunoreactivity to ETX is 10 times more prevalent in people with MS than in healthy controls, indicating prior exposure to ETX in the MS population.

C. perfringens epsilon toxin fits mechanistically with nascent MS lesion formation since these lesions are characterized by BBB permeability and oligodendrocyte cell death in the absence of an adaptive immune infiltrate.

And here is similar article, but from Medscape.

It seems as though any toxin from any source can, or could, be a serious problem. But it looks like the C. perfringens source causes damage specifically to myelin, which maybe others do not do?

Here’s beginning of Medscape article:

Medscape Medical News > Conference News

Further Evidence for Epsilon Toxin as MS Trigger

Sue Hughes

February 05, 2014

Further evidence that multiple sclerosis (MS) may be triggered by a bacterial toxin has been reported by researchers from Weill Cornell Medical College.

A team led by Jennifer Linden, PhD, presented research at last week’s American Society for Microbiology’s Biodefense and Emerging Diseases Research Meeting showing that epsilon toxin, which is produced by certain strains of the bacteria Clostridium perfringens, can kill myelin-producing cells.

Dr. Linden told Medscape Medical News that permeability of the blood–brain barrier and demyelination of neurons are defining characteristics of MS.

“It has previously been shown that epsilon toxin is associated with blood–brain barrier permeability, and that it binds to white matter in the brain — this is where the heavily myelinated areas are. Now we have shown that than this toxin kills oligodendrocytes — myelin-producing cells in the brain. This toxin specifically targets the same cells that are destroyed in MS. This gives further weight to our hypothesis that epsilon toxin may be causing MS.”

My state is endemic for mold/histoplasmosis. I can’t genetically detox mold. So, I wonder if my own state is keeping me sick? Love the hope that the article gives.

Where do you live? For me I’ve lived in the desert, near the ocean in San Diego, in New Mexico, Colorado, Mexico and North Carolina without noticing any significant changes in my health. I wonder in general if it’s more about staying away from bad indoor environments. I know of one woman who detoxed in Death Valley – felt GREAT – then moved out of her house in Baltimore, I think it was (high mold area I would suppose), get rid of her clothing, etc. and then was able to move into a new home and she was fine.

I wondered how I would do in humid N. Carolina but I didn’t really have any problems. I also lived in a house (spent most of my time outside) in low mold Las Vegas with a broken pipe in the bathroom – definite mold problems there – and I could tell.

I would also note that some people get relief from mold by living in primitive circumstances out in nature and do not appear to be to desensitize themselves over time or it takes a very long time to do it.

Ky.

KY

Kentucky

Kentucky. Very bad area for allergies and endemic for histoplasmosis.

Well I didn’t think my comment was published 😉

I live in a city bordering Berkeley and I can tell you it is bad here. I am trying to figure out where (and how) to move somewhere else as mold (and in my case chemicals in general) can make my symptoms go from mild to miserable almost instantly. Julie is correct, it is very hard to detect triggers if you are living in them, your sense of smell gets used to them and your immune system adapts as best it can so you just feel bad all the time. If you buy one of Shoemaker’s book get the first one “Mold Warriors” not “Surviving Mold” the one Julie Mentions. The new book is totally unreadable and the old one pretty much covers the same material.

Does anyone know where to get a “safe trailer” or “safe rental apartment” that is free of toxins?

thx

I know you can buy fully renovated Airstreams – to live in from healthy-homes – started by Tad Taylor – now run by his son. http://healthy-homes.com/. They also produce small prefab live in areas.

We should definitely get a resource center for this stuff up. I’m sure there are some on the web. I don’t know what kind of trailer Joey bought. I’m sure there are much less expensive ways to do it.

You definitely want to stay away from these horrible cheapo trailers that leak and have mold in them.

Thanks for reply. I was bedridden a number of years from fibro. I’ve made some health gains, enough to where I can do research to try to get better. Trying every angle to hit this from. I developed it after a period of intense stress – but also underwent a move and was getting migraines every night. We finally found the basement was loaded with mold. Couldn’t afford to have it professionally cleaned, so we did it ourselves. My health went really down – so don’t know if mold played a part or not, but apparently if people are recovering, it must. I can’t wait to move out of here – we have ionized the basement, and set off mold killer (has chlorine powder in it, and you add water, then leave house for hours) but I hate basements – will never have one again. I think they are invitations to trouble.

Want to find a safe place to live in within money limits. What states are supposed to be the best?

Want to move south, as winters hard on pain & hate staying indoors, but it seems as if it would be damper there because of humidity. Is this a correct assumption? Of course, NJ on list of bad places to live – but I knew that before reading it. Trying hard to “escape” but it’s hard.

Does anyone know of a good air purifier for the time being? I was going to buy the Airfree – because it uses heat to kill mold & toxins – with no filters to change.

Also, woman who wrote article said she takes a bunch of supplements to detoxify. Anyone know what these are? I got dr. to prescribe cholestyramine, but she said didn’t work for her.

Thanks for website and info. Wish I had found years ago.

I cannot recommend the Tad Taylor trailers. I bought one about seven years ago for A LOT of money and while beautiful to look at it was horrible from a health standpoint (mold and chemical smells) and quality control was poor with things like window cranks not working, cracks in the skylight, and the plastic protective film left on the metal walls in places. Some of this I wrote off to Tad passing away during the renovation of my trailer and his son having to finish it but Justin made no attempt to respond to the problems with my trailer once it was delivered to me. I was unable to travel at the time and live on the west coast so I had to deal with the purchase of the trailer sight unseen. I would recommend anyone buying from them go there and try out one of the trailers for a few nights before giving them any money. I talked others after the fact who had similar problems with them and their trailers.

I thought Joey said he had converted a cargo trailer (like the U-haul) trailers but I could be wrong.

What a shame. I never bought from Tad but he seemed so meticulous. I hope his son is doing a better job now.

Does anyone know if the online screening test for Visual Contrast Sensitivity available on the Surviving Mold website is an accurate way to determine if mold may be contributing to one’s health status? At $15, it is certainly more affordable than the tests I have been considering to assess the air quality in our home.

If anyone is interest in doing a low-cost online Visual Contrast Sensitivity test (free, with the option of making a small PayPal donation), one can be found at: http://www.vcstest.com/

Many thanks for this interview. I greatly appreciate all both Cort and Julie have done.

Thanks for your story Julie.

Julie,

I can’t thank you enough for the courage to write this piece and series of blogs . I understand and appreciate that it is so difficult, and has been for me as well to write about and connect with the deeply real experience about my 35 year journey of the unknown first coined “universal reactor” as it was called back in the late 70’s. -unexplained Fatigue…then…CFS..MOLD/MCS/….etc,etc..etc

going to Dr.Robert Giller – Alternative DO in Manhattan one of the first to test intradurmally for allergies – gave IV’s of Vit C – and put me on a 3 food diet for 3 months of Brown Rice,Pears and Chicken (Gluten Free???-WHO WOULD HAVE THUNK IT THEN?) – To get all the other foods out of my system -( I was really sick at 27 with a Masters Degree and great Exec Job I had to quit!!) ,I then went for 3 years to the amazing Dr.Sidney Baker-Then founder of the Geselle Institute Medical from Harvard – One of the first to use Nyastatin for “Yeast” in the Gut and also tested my apt in NY City for specific strains of mold!!! -so he too..could treat the environmental stuff, treated gut/food allergies/ and wanted me to start “food combining properly”…cutting edge doctors performing tests that were then unheard of and now are the new age wave!!…Also, seeing…Dr Robert Zann Sr.in Kingston NY – (mid 80’s – same..who .wrote”Why Your House May Be Killing You”). He wanted me to move to an area of NY State that the environmental ions were testing healthy….

And, so importantly, I was a patient and friend of Dr Albert Robbins, in Boca Raton, Florida…from the week I moved to this area from NYC. He is still with us, but so unfortunately, closed his practice about 4 years ago due to extreme illness. He is one of the greatest physicians and experts in the Alternative Medicine,DO arena and Environmental Medical area.

Dr Robbins and my primary care physician were my go to docs for years. Dr.Robbins correctly and methodically diagnosed my CFS 10 years ago – also sent me to Head of Immunology at a major hospital for ” confirmation” for insurance purposes …Al treated me for MCS gut issues, and once again alot of the “new” treatments were standard for him – he gave me gammuglobulin,Vit C, IV’s – treated me for colds , the flu, etc- for 20 years all while I worked successfully 24/7 in an executive capacity.

After six months of colds, sinus, down-hill never-ending fatigue and cognitive fog – One of the worst days of my life – was when I finally had to stop working….I have tried to walk in two worlds – our world and the poker face world that I’m OK and people thought I was feeling “much better” since I looked better than just fine…when I pace enough to be out.

I can’t work and while I’m absolutely not bedridden- I have improved and relapsed and improved and relapsed. I’m convinced that that likelihood of a major relapse diminishes greatly if the environment,ie MOLD, MOLD, MOLD SCENTS, ETC are eliminated or minimal.I can tolerate much more if my immune system is stronger – I have been in a slow relapsing state for the past 3 years. I kept thinking I’ll be fine and I just have to get through this and this and this.personal situation that is almost over…type A thinking like most of us! The last six months have been a killer – It’s showing to

others, friends, family and acquaintances. Its time for me to take hold and no doubt for me – the environment/Mold is the first line of defense for me – then immune modulators, foods, etc.

Dr Al Robbins continued to treat me for years – but I was truly fortunate to find a clinical trial for Procrit Headed by Dr.Nancy Klimas then at University of Miami in late 2003 It was four months before my call was returned and the trial lasted for 10 months (traveling 1 1/2 hrs each way 2x a month). I did not become a patient of Dr Nancy Klimas until almost a year later (mid 2004). She is one of the top in the world – while there are no magic bullets – Dr Klimas knows the latest of what is possible. I just saw her this week…

Julie – Thank you truly again! Cort, thank you for creating this space to profoundly spread amazing knowledge and to remind me of what I must do to get myself back!!!

Ellen, How did you get an insurer to pay for your gamma globulin? Also, can you mention what drugs or protocols Dr.Klimas used that you believed might be helpful? If you prefer you can e-mail me at debo@tiac.net. I have been sick since 1989 and I would like to know what I am missing.

Thanks,

Deborah

Thank you for this article.

Clove oil is THE way to kill mould, according to Australian scientist and radio presenter, Shannon Lush. 1/2 teaspoon in a small spray bottle filled with water. Spray a mist – but don’t saturate. Leave for 24 – 48 hours before touching/cleaning/painting, etc – the clove oil needs this time to kill the mould before you go about spreading it around again. Shannon Lush, who is also the author of several books, insists that clove oil works, but that supermarket mould products do not, merely bleaching the mould rather killing it.

I suffer with MCS and I tried this in my home. On one ceiling which has mould on it I used clove oil. In another area in the house I did not use clove oil. After 48 hours I painted over with safe, zero VOC paint (Resene). On the area where I did not use clove oil, the mould came back through the paint within only three weeks. On the area where I used clove oil, on the other hand, three years later, the mould has not returned.

A bottle of clove oil cost about $6 and will last many years.

Although clove oil is completely natural, a person with MCS needs to be careful, as with other oils like eucalyptus and tea tree, for example, not to get it pure on your fingers. It is a strong oil in its pure, undiluted form. Use some poly gloves and you’ll be fine.

I hope this helps.

I wish I’d found this site years ago! It helps to alleviate the sense of aloneness I feel. Just within the last few months my throat has become so lumpy feeling, that it’s difficult to talk. You guys are my lifeline! My thanks to you Julie and Cort!

I got sick as a sort of flu-like illness swept through my college, affecting people in different living facilities. Some people recovered, but I remained chronically ill. I had a co-worker who got sick around that same time. He also developed a flu-like illness just after returning from a Hawaiian vacation.

I very much doubt that mold was a trigger in these instances, but we’ll have to wait for further research results to see – certainly all avenues should be explored. My own theory is that this is an entero-virus like polio that infects the nervous system, but I’m no expert.

A flu-like illness was exactly what was involved in the Lake Tahoe incident and mold was very much a factor there. I was also triggered by a flu-like illness, and the mold in my home was not discovered until a year later. Unfortunately seems we will have to wait a long time for research to come around as no one is looking at the mold angle.