Intermittent fasting has been crucial in my long-lasting CFS recovery. – Dr. Courtney Craig

The pleasure of eating good tasting food is undeniable, but food can have a dark side for people with Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS) and Fibromyalgia (FM).

Digesting food, for one thing, takes work – lots of it. In energy-depleted disorders like ME/CFS and FM the energy that goes into digestion could conceivably have been used for healing.

If you have blood volume issues, eating can cause your blood to rush to your stomach leaving you depleted elsewhere. The cramping, bloating and other gut issues common in Fibromyalgia and ME/CFS take their toll as well.

Dr. Cheney once wryly said that if only ME/CFS patients didn’t have to eat they would get a lot better. Eating small meals is definitely the way to go for many people with these disorders, but what about occasionally cutting out meals altogether? Would that help?

Dr. Craig on Fasting

Dr. Courtney Craig, D.C., a former Chronic Fatigue Syndrome patient, asserted in a recent blog “Cellular Spring Cleaning: Intermittent Fasting for CFS” that it can. In fact she found that intermittent fasting helped her avoid relapses and stated it has been ‘crucial’ in her long term recovery.

That got my attention. I’ve tried fasting before. It definitely helped before it wiped me out, but Dr. Craig’s fasts are nothing like the fasts I tried. Her quickie ‘made for ME/CFS and FM’ type fasts last 8-12 hours and start after an early dinner and end with a late breakfast around noon. Fasting while you sleep is an idea I can get my head around.

Instead of doing them for days, you do short fasts once or twice a week. I’m definitely going to give them a try. Fasting fits my favorite criteria for treatments: it’s cheap – in fact, you save money doing it – and you can do it from home.

Dr. Craig warns that people with uncontrolled hypoglycemia, adrenal fatigue, or thyroid problems could have problems with intermittent fasting.

Find out more about Dr. Craig’s ME/CFS and FM fasting protocol including what kinds of ‘foods’ to eat to get you through the fast in her blog “Cellular Spring Cleaning: Intermittent Fasting For CFS“.

I was eager to learn more.

Dr. Courtney Craig (DC) on Intermittent Fasting in Chronic Fatigue Syndrome and Fibromyalgia

Simply by avoiding meals for 12-18 hours periodically I have been able to stave off relapse and even “bad days.” – Dr. Courtney Craig

The Nitty Gritty – Doing the Fast

When do you know if should break a fast? I have heard of fasters having to go through a kind of rough period before their body adjusts, but are there any signs that signal it’s time to cut short a fast even if you haven’t gotten to the 8-12 hour mark? What if you’re feeling great at noon the next day? Your energy is up and your desire for food is gone – what about continuing further?

I can’t stress this enough: I don’t recommend intermittent fasting until the individual has switched over to a low carbohydrate, nutrient-dense diet for at least 3 months or longer. It is vital to first stabilize blood sugar (insulin) and leptin levels. Otherwise, fasts for 8-18+ hours will feel like starvation and can seriously tax already fatigued adrenal glands and disrupt normal thyroid function.

It is also vital to continue to drink water while fasting. Those with POTS or hypotension may also need to replenish electrolytes.

Fasting is very much an individual experience where some will be able to go for longer periods than others. If you can’t fast for 24 hours, 14-16 hours may still have a beneficial effect. It’s important to just be aware of how you feel while fasting, take in adequate liquids, and not exceed your limits. Monitoring blood pressure may also be a good idea during fasts. I encourage working closely with a nutritionist or clinician who is familiar with intermittent fasting.

When should you break the fast? A good rule of thumb in my opinion is to only eat when you’re hungry. Hunger hormones like leptin and ghrelin tightly regulate appetite. However, in individuals who eat a high carbohydrate diet (standard American diet) leptin resistance can occur. Blood sugar quickly drops with leptin resistance resulting in hypoglycemia and severe hunger pangs.

What about that last dinner? Should it consist of extra protein? Do you have any recommendations?

An early dinner that is low in carbohydrates (primarily coming from vegetables) with moderate protein and high in healthy fat is my usual dinner. Loading up on carbohydrates before a fast may seem like the logical thing to do since carbs are stored as glycogen (similar to how athletes carb-load before a race), but this defeats the purpose of the entire fast. In order to get the cellular benefits of fasting, one must deplete glycogen stores and burn fat as fuel through a process known as ketosis.

Insulin needs to be kept very, very low to promote the creation of ATP from fats and not glucose.

Ketosis can be measured easily using urine test strips to look for ketone bodies. One ketone in particular, β-hydroxybutyrate, is beneficial to mitochondria. It acts as an antioxidant and increases gene expression of oxidative stress resistance factors (5).

This important discovery potentially creates a “biohack” for intermittent fasting—a simple trick I use if I get hungry during a fast. In theory, as long as you can remain in ketosis (fat burning mode), consumption during a fast will not undo the beneficial effects. This can be achieved by eating small amounts of quality fat (I like coconut butter or butter coffee/tea) which will have little effect on insulin levels, maintain ketosis, and tide you over for another few hours before breaking the fast.

You stated that fasting has helped you avoid relapses. Are there times when you were not doing well that you thought, “This is time to give my body a break and do a short fast”?

Even in getting my CFS under control after 15 years, I am not immune to the occasional flare-up when I get lazy about diet/supplements or have a lot of stress in my life. Every so often if I feel my symptoms returning or a cold coming on I will focus on trying to do a 14-16 hour fast to boost my immune system. With that (and the combination of diet/supplements) my flares are usually only 1-2 days in duration.

However, in general I try to fast at least once or twice per week for maintenance. I have noticed that I’m much more resilient to stress, poor sleep, and have far less post-exertional malaise. I’m now able to go for long walks (4-5 miles), do basic strength training, lecture for 7 hours, and bustle around NYC without the usual soul-crushing fatigue.

My sister can go on week-long lemon juice fasts and end them up feeling great! When I’ve fasted in the past I’ve always experienced times when the world just seems brighter. My mental clarity is increased, my body feels better, but even if I’m drinking protein shakes I can’t fast for more than a day and half without feeling like I’m going to fall apart. Why can she whip off a week while I’m struggling after a day?

I can’t fast for 24 hours either—at least I’ve never buckled down and tried it. In theory, I believe the effect can be the same with more frequent, shorter duration fasts. I could only guess why it’s easy for her and not you … maybe her diet is lower in carbohydrates? Higher in good fats? Could be related to hunger hormones as well?

The Science

How did you get into fasting? I’ve tried it intermittently, but I don’t know if I’ve ever heard it discussed with regard to ME/CFS or FM. It, however, became an important of your treatment plan. How did you find out about it?

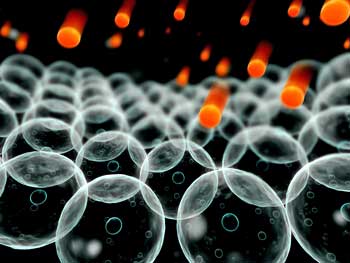

Caloric restriction (fasting) has long been understood to reduce oxidative stress and slow mechanisms of aging in various organisms, but only recently have the biological reasons for this begun to be understood. The effects of fasting are believed to be controlled by the sirtuin family of proteins. The seven known mammalian sirtuin proteins control a variety of functions including aging, programmed cell death (apoptosis), transcription, cellular energy efficiency, mitochondrial biogenesis, antioxidant mechanisms, and circadian rhythm.

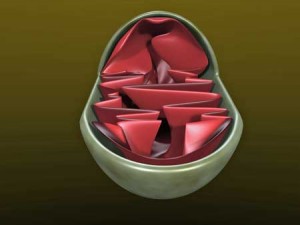

I had the opportunity last spring to attend the International Conference on Human Nutrition and Functional Medicine where the theme was mitochondrial health. In attendance was Matt Hirschey, PhD, who has authored several landmark papers that demonstrate that the cellular benefits of fasting are due to the effects it has on sirtuin proteins, specifically SIRT1 and SIRT3 (1); (fig. 2).

SIRT1 stimulates receptors that up-regulate antioxidant molecules (glutathione), increase mitochondrial mass, and inhibit NF-kB—a very important transcription factor that promotes inflammatory cytokines and is implicated in CFS pathogenesis (2). SIRT3 is located within the mitochondria where it also stimulates antioxidant molecules to reduce oxidative stress.

However, new research has also shown that fasting dramatically affects the immune system as well. Scientists at the University of Southern California (USC) found that 2 to 4 day fasts significantly reduced white blood cell counts in humans as well as mice. In the mice group that fasted for 72 hours, stem-cell based regeneration of immune cells occurred. The USC group concluded that fasting may be a viable option to lower the toxicity of chemotherapy in cancer patients by bolstering the immune system with healthy cells (3). I’m intrigued that fasting may have a similar effect to the drug Rituximab which acts by eliminating dysfunctional B lymphocytes and indirectly stimulates the production of new lymphocytic stem cells from bone marrow.

The nutrition naysayers shudder at the idea of voluntary caloric restriction. We are taught that caloric restriction can disrupt hormone balance, stress the adrenals, weaken the immune system, and even result in excessive oxidative stress.

But I was then introduced to the notion of hormesis, a pharmacological concept that indicates that, where a dose-dependent curve is present, low doses of an agent can have the opposite effect of high doses of an agent. This led me to have a broader understanding of caloric restriction at a practical level.

In the mitochondria this theory is termed mitohormesis, where small amounts of oxidative stress are protective and lead to resilience to further oxidative stress. Hirschey and others predict this resilience is produced when SIRT proteins are stimulated during fasting (2). Fasting thus appears to build a cellular resiliency which is lost when the hormetic threshold is exceeded. Since ME/CFS is defined by chronic oxidative stress, building cellular resiliency could potentially help undo that vicious cycle to improve energy production.

Your blog suggested that during fasting your body gets rid of damaged mitochondria and that clears the way for new mitochondria to be produced. Is that correct?

Fasting leads to mitochondrial autophagy (self-eating), also known as mitophagy, where genes are stimulated in the mitochondria to undergo apoptosis and destruction by intracellular enzymes. Death and destruction of the cell’s energy factories may seem like a bad idea at first, but when those factories are already damaged by chronic oxidative stress, a bit of remodeling is extremely beneficial.

From my understanding it is not completely understood how mitophagy is controlled, but studies have shown that insulin suppresses mitophagy while glucagon stimulates it. So during fasting, insulin is kept very low and glucagon is elevated which leads to mitochondrial recovery. (4)

——————————————

Dr. Courtney Craig was first diagnosed with CFS as a teen in 1998, and recovered in 2010 utilizing both conventional and integrative medicine. Trained as a doctor of chiropractic and nutritionist, she now provides nutrition consulting and blogs about what she’s learned on her website.

Check out her Health Rising blogs here.

___________________________________

1 Merksamer PI, Liu Y, He W, Hirschey MD, Chen D, Verdin E. The sirtuins, oxidative stress and aging: an emerging link. Aging (Albany NY). 2013 Mar;5(3):144-50. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23474711

2 Morris G, Maes M. Increased nuclear factor-κB and loss of p53 are key mechanisms in Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS). Med Hypotheses. 2012 Nov;79(5):607-13. Epub 2012 Aug 27. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22951418

3 Cheng CW, et al Prolonged Fasting Reduces IGF-1/PKA to Promote Hematopoietic-Stem-Cell-Based Regeneration and Reverse Immunosuppression. Cell Stem Cell. 2014 Jun 5;14(6):810-23. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24905167

4 Cuervo, A. M., Bergamini, E., Brunk, U. T., Dröge, W., French, M., & Terman, A. (2005). Review: Autophagy and Aging. Autophagy. 1(3), 131-140. http://www.landesbioscience.com/journals/autophagy/cuervoAUTO1-3.pdf

5 Shimazu T, et al. Suppression of oxidative stress by β-hydroxybutyrate, an endogenous histone deacetylase inhibitor. Science. 2013 Jan 11;339(6116):211-4. Epub 2012 Dec 6. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23223453

A less elegant, but perhaps equally valid explanation as to why fasting may help symptoms of CFS and FMS is because of the strong association between these an SIBO. In SIBO, there is impaired small intestinal motility with the migrating motor complex. It is advised for people with this to eat as infrequently as possible (ie no between meal snacking), to allow as much clearing of the small intestines into the colon as possible to keep bacterial counts down, as food will immediately abort any migrating motor complex activity from happening. Fasting would just give more time for the small intestine to clear itself into the colon, reducing upper bowel organism counts, fermentation, immune activation and toxic byproducts. I have found that fasting for about 18 hrs once or twice per week helpful in managing my symptoms.

Thanks for adding that potential extra added benefit – talk about inner cleaning 🙂

I definitely have problems with food. I’m pretty good in the mornings but once I eat lunch which for me is the first comparatively large meal of the day I get an immediate flag in energy and need to sleep.

IBS has been a major problem for me constantly and back when I had to travel for business purposes the only way I could manage (air and train travel and IBS isn’t a good mix) was to eat nothing or very little over the period I was away from home which often meant no food for 24 hours. It might have been adrenalin but I felt much better and more energetic when I didn’t eat. Conversely on those occasions where they laid on a meal or buffet it was a very long day.

I have to agree with Cheney that we seem to do much better without eating – not only impossible but food is one of the few available pleasures (up to a point).

Strangely enough when I first became ill I was on a fitness kick and was exercising every day and on a very restricted diet so perhaps too little is as bad as too much.

Small healthy meals and an occasional short fast sounds a sensible approach especially if insulin/leptin resistance plays a part in ‘fatigue’.

I contracted fibromyalgia while exercising fanatically – I was a fitness freak. I blame a very unfairly stressful job for the fact that my health got messed up in spite of being fit. I thought that being super fit immunised one to stressful situations and even chronic stress. I was wrong. It was YEARS before the medical dullards diagnosed me, I was complaining of pains preventing me exerting myself as I was accustomed to, and sleep deprivation in spite of physically tiring myself daily. They gave me all the blood tests etc and said there was nothing wrong with me – for years. I even stayed in the job from hell until I actually got properly diagnosed and a specialist said “get OUT of that stressful situation”……!

I think my condition was caused to get far worse by battling on for years not knowing what I needed to do to cope. I am so thankful that I did move quickly into a completely different occupation that I loved, although in hindsight I really should have taken a total break for a good while – the wise specialist actually recommended a year on the beach on a Pacific Island, and I think he was probably right.

I know where you’re coming from….I would that have thought being super-fit would have inoculized me against ME/CFS and other illnesses. I imagine it does do so for some illnesses. It sure didn’t – and I was not under undue stress at the time….The whole thing is just a mystery. .

I’ve heard of quite a few people who were really fit when they came down with ME/CFS.

Hi Cort,

Thanks for all your great work!

I would be interested in hearing more of Dr Craig’s ideas about diet. I know I do a lot better when I eat a high protein/low GI diet. I have tried fasting before, but have a lot of difficulty going without food because I get sooooo hungry. Having said that, I do eat a lot of wheat based carbs so I am now thinking about changing what I eat. Any advice from Dr Craig on that score would be most welcome.

Hi Barbara,

I can’t recommend consumption of wheat gluten for anyone with this condition. It just promotes gut leakiness and potentially autoimmunity via molecular mimicry. Getting off gluten completely has helped many, many CFS and fibro patients improve.

It helped me with my bloating and to some degree with fatigue. I’ll never go back – I thought I was going to get stretch marks!

This study (in rats, but still interesting) shows how acute fasting and too few calories increases oxidative stress and other negative parameters. Moderate caloric restriction on the contrary increases antioxidative capacity and has several other benefits. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/m/pubmed/23682026/

This is in line with my personal experience. Fasting is a no-no, it increases my OT, pain and PEM. Eating small meals, very small meals, keep my blood sugar stable and my digestive tract working properly.

And as for the «high» or «kick» one can experience fasting, I seriously doubt thar our bodies need that kind of metabolic strain and -stress. Evolutionary we’re wired to survive even when the food is scarce, but it’s a stress response to get us to run out fighting and hunting. I believe we need food as a continuous fueling, not intermittently.

Nope… you are wrong. Humans adapted to use ketones as fuel in every organ, including the brain, and that was what allowed us to dominate even the most inhospitable places in the world, where food was scarce for months. The Chinpanze’s for example, cannot feed they’re brain with ketones and only appear in places where natural food abound in nature.

VERY interested in this.

“…..I can’t stress this enough: I don’t recommend intermittent fasting until the individual has switched over to a low carbohydrate, nutrient-dense diet for at least 3 months or longer. It is vital to first stabilize blood sugar (insulin) and leptin levels. Otherwise, fasts for 8-18+ hours will feel like starvation and can seriously tax already fatigued adrenal glands and disrupt normal thyroid function……”

I have had Fibromyalgia for 20 years. My weight ballooned due to inability to exercise much, which caused a vicious circle of problems including sleep apnoea. In desperation 1 year ago I tried the Atkins diet seeing nothing else worked. Atkins has allowed me to lose 20 kgs so far and enabled me to at least exercise a bit more than if I was still obese (I am still 130 kgs, WAS 150!!). I do think the elimination of all carbs except a bare minimum actually helps cope with the fibro anyway.

Because going off carbs breaks the cravings for them (after the first 3 days or so of cravings hell) I have been able to skip meals when too busy, without getting the terrible faintness that I used to get. I am living on burning fat for energy, not carbs. I already suspected that simply “not eating” did make me feel better, I will now definitely try this as a deliberate tactic and see what happens.

Something I had to surmount after a few weeks of Atkins diet, was agonizing night cramps in my calf muscles; thanks to Google searching I found others who had the same experience, saying that remedying magnesium shortage was the solution, which certainly worked for me. Of course I took multiple vitamins and minerals all along like Atkins dieters usually do, but there was nowhere near enough magnesium in them.

Fibre for bowel health is assured without mucking up Ketosis, by using flax seeds and “Konjak” as part of the diet. These are so effective for fibre that only small amounts are necessary (too much, or not drinking enough water with them, will constipate you), and they are low GI.

Ah! again…. I must say this site has much to enlighten the information craving soul of a CFS and FM sufferer. For years now, I have understood: if I needed to go to work or do anything in the day that required staying upright for more than a couple of hours, I had to forgo breakfast and lunch if necessary. I didn’t understand why until now. I knew that eating caused me to have to have a nap even if I had just slept minutes before my meal. All that I have just read concerning fasting for CFS has just explained why. I had been on a low carbohydrate/high nutrition diet for the last few years due to the benefits I found it had on FM. I have strayed from that in the past few months but had planned on going back. Now I am deffinately starting today with my trip to the local market so that I can start a fasting ritual as mentioned in this new information. I already know the benefits on a short term basis. I am looking forward to seeing if there are any long term benefits as I am still unsure how long I will feel well with my current treatment. Being 48 years old; the age slowing benefit of fasting is quite intriguing as well.

Indeed! Anything to try and slow down the march of time – which may be marching faster in people with ME/CFS and FM. Studies in both have found shorter telomere’s – something that has been associated with aging.

I believe they’re also associated with increased oxidative stress – which short fasting may help reduce.

Someone sent this in – some more evidence that fasting might be helpful

“Cort, you should be aware of CW Cheng et al., “Prolonged Fasting Reduces…and Reverse Immunosuppression”, Stem Cell Journal out of UCLA.

This does conform to the ketogenic diet ….

I thought that fasting increased cortisol levels and that was bad for you? My weight doesn’t change if I fast, even went up a couple of pounds on one occasion – I don’t seem to be able to convert fat to energy – any advice on that?

I eat early and in that sense I guess I “fast” overnight for 12 hours, although I’ve never considered it a fast as I then eat breakfast. I usually feel better after lunch.

Fasting has been on my mind more and more lately and thanks Cort for posting this article. I have had good success in the past with very bad flare ups through fasting. Several things I have learned, as mentioned in the article, it is much easier once the body adjusts to a low carb diet. Secondly, as a previous poster mentioned, SIBO also plays a part. I personally have a very hard time eating a diet high in insoluble vegetables without experiencing alot of general pain especially in the sinuses. On the flip side too much insoluble leads to more bacterial overgrowth and a over all poison ed feeling. Long story short. Some gut repair is needed before being able to completely switch the the low carb, nutrient dense diet. I think once this is achieved fasting will continue to assist in detox, gut repair, immune system and mitochondria repair.

One of the side effects of putting myself on a year-long Protein Sparing Modified Fast to lose weight (around 60 pounds), was that I discovered that if I stayed in ketosis, my brain worked better. I’m trying to write the Great American Novel, and I’ve had CFS for 24 years, and it’s hard to write that way. I’m trying the fast again because a few of those pounds crept back on (you can’t fast forever), and this post is giving me all kinds of ideas about timing, and adding fat to extend the fast, etc. – but guidance would be better.

Do you know if Dr. Craig has any experience with a PSMF? Or has any ideas how to both lose weight and keep the brain using ketones for energy? When not fasting, I’m strictly low carb. Eating regular food just dumps me into the ‘staring at the wall stage’ of CFS energylessness.

A PSMF sounds problematic to me since it also restricts fats. To stay in ketosis opt for nutrient dense fat choices–particularly saturated fats and medium chain triglycerides which benefit the gut.

Now I understand better why I changed my diet after getting sick. Before, I used to eat a lot of meat, but since I gradually shifted to seafood. I feel better with a lighter diet, that’s why.

Hello my name is Tammy and I have Fibromyalgia

I have had this disease for over 20 yrs now I take no meds except once in a while Ibruprofin @ 600 mg I take 2 thats it. Ever yr I fast for 30days 1 month I start fasting at 3 15 am until 7 pm and then start all over again the next day for the rest of the 30 days, Its my holy month of ramadan and it is manditory for me to do this. Its hard but I some how get through it.This yr the heat here in Egypt is a big factor for me this moring I woke up feeling weak and very thirsty. I alos suffer from hot flushes which makes thirst very difficult to control, I had to break my fast early with water but waited to eat til the right time. I love doing this because it detoxes the body of harmful toxins. We don’t eat a lot of meat mainly chicken and fish and a lot of veggies and fruit. I make my own seafood soup and do all the cooking because i can control how much of everything is in my food.

I have never been able to fast for 24 hours without pain levels increasing rapidly and in my young days had to adopt a Zone diet to control hypoglycaemia which is a perpetuating factor for trigger points. These days I fast normally every night for at least 14 hours but didn’t realise that it was doing me good. I believe I can only last that long now because of the pregnenolone I take which normalises cortisol levels and which, I believe, also controls blood sugar levels.

Dumb me, having CF/MES symptoms since dr Craig has too, until last year (2022) when i first discovered intermittent fasting. I studied so much the wrong places and made so many useless, expensive and sometimes painfull exams (like muscle biopsy) searching for enzimes deficiencies. After some 7-8 months of lowering carbohidrates and implementing IF the hard way and more recently making therapeutic fastings of 24-72hours I’m finnaly restablishing a reasonable standard of life quality. My blood tests improoved, my daily energy and mental clarity are ao much better now that there is not much risk for me to going back to what i used to be…