A Neuroinflammation Story

Who knows how it started? Did those two mysterious red dots on a vein on her arm mean anything? Could that businessman who sneezed on her in the subway triggered her illness? Or did her biological stars just suddenly align in the strangest configuration ever?

Nobody ever figured out what triggered Susannah’s “month of madness” and in the end it didn’t matter. What mattered was that a young New York Post reporter quickly got very ill and for quite a while nobody knew what to do about it.

This is not a story about chronic fatigue syndrome or fibromyalgia but it could be. The subplots running through it – a woman with the mysterious illness, the predisposition to look for a psychological cause, the negative test results, the misdiagnoses, the strange “brain” symptoms – could be patched onto many ME/CFS and FM stories, and indeed other mysterious illness stories.

Susannah’s story shows how bad neuroinflammation – a possible cause of chronic fatigue syndrome and/or fibromyalgia – can get, how much remains to be learned about the brain and at the same time how quickly the medical researchers are moving forward. Ultimately her story provides hope for people with mysterious central nervous systeme disorders.

Susannah chronicled her story in a best-selling book called “Brain on Fire: My Month of Madness“.

Her Brain on Fire

Susannah Callahan was a young talkative, funny and dedicated New York Post reporter when her month of madness began. First came a unreasonable fear of bedbugs, then a flu-like episode, then a search through her boyfriend’s emails and letters. Even as she was appalled at the boundaries she was breaking she keep breaking them. She didn’t feel like herself; she was anxious, nauseous and unsettled.

When her left hand went numb her gynecologist fixed her up with a neurologist described as “one of the best in the country”. Except for some swollen lymph nodes. though, all her tests were normal. Maybe, he said she had mono. Basically he told her she was OK and to relax.

But she wasn’t. Over the next week she had trouble sleeping, was overwhelmed by the colors and bright lights in the city, and her erratic behavior increased. Her moods whipped from one extreme to the other. She thought she was having a nervous breakdown. When she had a seizure in the middle of the night her boyfriend called 911.

Back to the neurologist she went. He proposed she was working and partying too hard and not sleeping. All she needed was rest and to get off the booze. A psychiatrist diagnosed her with a form of bi-polar disorder and put her on medication.

Meanwhile her descent continued. Wild paranoid thoughts filled her mind. She accused her parents of kidnapping her. She tried to dart out of a moving car. Despite the seizure medication she had another one.

Back again to the prominent neurologist she went – this time with her mother – who demanded more tests and better answers. After a normal EEG, however, the neurologist again diagnosed her with alcohol withdrawal. Despite her mother’s protests that her daughter had not had a drink in a week, the neurologist told Susannah to stop drinking and take her medication. (In his notes he reported she was drinking two bottles of wine a night).

Psychosis

Her mother would have none of it and Susannah was booked into 24 hour epilepsy EEG monitoring unit at the New York Langorne Medical Center. As she entered the hospital she had a massive seizure.

Her delusions mounted. She asserted her parents were turning into other people. She felt people on TV were talking about her. She tried to escape. She declared she had multiple personalities. She became so unmanageable she was in danger of being admitted to a psychiatric hospital. Hints were made that that was a place she wanted to be.

Five doctors were quickly on her case. Four days later four more including an infectious disease specialist joined on. As her psychoses began to recede leaving her in a zombie-like state at times a lumbar puncture was scheduled.

With her options running out Susannah was in danger of ending up in a psychiatric ward – perhaps permanently

The slightly elevated levels of white blood cells found – the first abnormal test results yet – raised hopes she had an infection but further testing at the CDC and New York State Labs found no signs of infection (herpes, Lyme disease, tuberculosis or others) or autoimmunity. Her MRI and CT scans continued to be normal. When a top doctor abruptly quit her case her parents became distraught.

With few positive test results and her options running out, Susannah was in danger of being diagnosed with a mental disorder and ending up, perhaps for the rest of her life, in a psychiatric hospital.

Then one more doctor, Dr. Souhel Najjar joined the team. Najar’s ability to solve some mystery cases at the hospital had made him the go-to man for difficult cases. He discarded the psychosis diagnosis and despite the negative autoimmune test results he put her on five rounds of IVIG.

Encephalitis

Susannah, however, continued to worsen. She was diagnosed with catatonia and began making strange Frankenstein-like movements with her arms. Najar ordered another lumbar puncture. This time there was good news; a quadrupling of her white blood cell counts indicated central nervous system inflammation was present – lots of it. Her diagnosis was immediately switched from psychosis to encephalitis.

Najjar’s first examination of her proved to be groundbreaking. When asked to draw the numbers on a clock she fit all twelve hours into the right side of the clock leaving the left side blank. That clue suggested that the right hemisphere of her brain have been ravaged by inflammation – probably by an autoimmune process. Her brain, he said, was on fire.

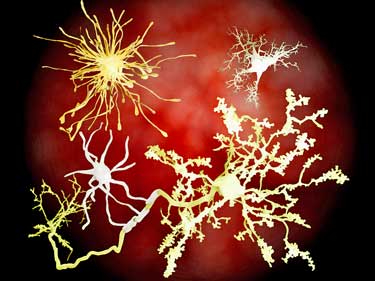

The probable next step was steroids, plasmaphoresis and/or more IVIG. First, though, Najjar wanted a brain biopsy. Reluctantly her family agreed. The biopsy showed massive numbers of microglial cells attacking her nerves.

The biopsy indicated Susannah had an as yet undiagnosed autoimmune disorder. (She had been tested for only a few out of the hundred or more autoimmune disorders before).

The treatment regimen was brutally simple: massive doses of steroids infused into her over three days to stop the immune attack in its tracks followed by lower doses to quell the remaining inflammation over time.

Meanwhile her blood was sent to a Dr. Joseph Dalmu at the University of Pennsylvania. The results came back positive.

A New Disease

Four years earlier Dalmau had described four young women with psychiatric symptoms and encephalitis. Testing revealed NMDA-receptor antibodies were attacking the hippocampus – the center of memory and learning – and the frontal lobes – the center of higher functioning and personality.

Two years later Dalmau published an account of twelve women with what he now called anti-NMDA receptor autoimmune encephalitis. A year later a hundred women had been identified. By the time Susannah because ill over 200 had been. When her results came back, Susannah Cahalan was the 217 woman to become diagnosed with the illness.

In retrospect, the course of the disease had been very clear. The initial flu-like symptoms reflected the immune system starting it’s ramp up. The psychiatric symptoms occurred as the antibodies attacked the nerves in her hippocampus and frontal lobes. The catatonia was the result of progressive damage.

Recovery

The brain is radically resilient. Susannah Cahalan

The steroids probably saved Susannah from entering a life-threatening stage of catatonia but her brain damage was severe. She was extremely cognitively challenged and had trouble speaking and smiling. Whether she would ever return to her former self was unclear.

Najjar decided Susannah was too ill to try anything but the nuclear option. He would hit her overactive immune system as hard as he could and in as many ways as he could. Susannah would again get massive doses of steroids, but this time they would be followed by plasmaphoresis to purge her body of the antibodies, and then IVIG to further neutralize the antibodies. She would do this several times. Over the next six months or so she would get 12 IVIG infusions.

Besides this she would be on five drugs: Atvian to prevent catatonia, Geodon for psychosis, Trileptal for seizures, Labetolol for high blood pressure and Colace for constipation and get speech and cognitive retraining.

She began a slow recovery. A month later she wrote that her first real glimpses of recovery had occurred. Five months later she made her first tentative return to work in the New York Post newsroom. A couple of weeks later she dropped her anti-anxiety and anti-psychotic drugs. A year later she felt she’d returned to full health.

Conclusions

..I realized now that my survival, my recovery – my ability to write this book – is the shocking part. ” Susannah Cahalan

Susannah was one of the lucky ones. Without the seizures (not everyone has them) she would have ended up in the psych ward instead of the epilepsy ward. Perhaps she would have found another Najar there – a doctor on top of his game who was aware of a rare disease that had been recently discovered – but there’s no telling. However it happened she was lucky Najar.

(Another case mentioned in the book describes a more typical story. A sophomore in college became paranoid, checked herself into a psych ward, was diagnosed with “psychosis, not otherwise specified”, sedated and released. A month or so later she was admitted to another psychiatric institution. The doctor there rejected the anti-NMDA receptor hypothesis because she wasn’t having seizures. She returned home and eventually became unable to add or do basic physical tasks. She returned to the hospital where her doctors, for the first time, informed her parents that her MRI test a year before indicated she had inflammation.

As they prepared the IVIG a blood clot in her brain caused a massive seizure. During her seizure her father pushed Susannah’s article describing her illness into the neurologists hands. Her test for anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis was positive and she was air-evacuated to the University of Pennsylvania where Dr. Dalmau successfully treated her. She returned to complete health. (Despite proper treatment about 20% of patients are permanently disabled or die.

Thanks to the work of Dalmau, Najjar, Susannah and her book those kinds of stories are disappearing. Since Susannah has diagnosed in 2009 over 2,000 women have been diagnosed with the disease.

The New York Langone hospital also responded well. It put ten doctors on her case and her treatment costs were over $1,000, 000. There’s something comforting about the extent to which the medical system can go at times.

Susannah’s story also revealed the limits of medical technology and how difficult making a diagnosis is the face of limited test findings. Susannah’s MRI’s and CAT scans were never abnormal. Even after she’d had seizures, psychotic episodes, sensory distortions and trouble writing and responding to people the wide blood cell counts in her lumbar puncture – indicating inflammation – were not particularly high.

Her possible diagnoses at that point included hyperthyroidism, lymphoma, Devic’s disease and paraneoplastic syndrome. Only after she started drifting into catatonia were the markedly increased white blood cell counts indicative of severe inflammation present – and only after her antibody tests came back was her diagnosis ensured.

Movement in the Medical Community

Anti-NMDA-Receptor-Encephalitis has surely been around for many years. A search through the medical literature revealed some case reports dating back to the 1980’s but that was it until 2005. Once the disease had a name and a test progress was pretty rapid, however.

At the time of Susannah’s diagnosis in 2009 Najjar believed that 90% of the cases went undiagnosed. Subsequent research suggests that was probably an underestimate. Dalmau’s found other receptor seeking autoimmune diseases since then. He believes by the time it’s all said and done more than twenty autoimmune diseases may be causing cases of”unidentified psychosis”, “encephalitis of unknown origin” and other idiopathic diagnoses.

The understanding of the role anti-NMDA antibodies has broadened as well. They are now believed to play a role in at least some cases of autism, schizophrenia and dementia. Enough evidence has accumulated for a subspeciality called autoimmunity neurology to appear. It’s clearly a growth field.

Susannah’s story is ultimately a hopeful one. The medical research community is responding. How many people with a now mostly treatable disease entered and remain in psychiatric wards is unknown, but since 2009 thousands of women have now been identified with the disorder. Susannah and others have created the Autoimmune Encephalitis Alliance to help spread the word.

It’s not at all clear how, if at all, any of this applies to ME/CFS or FM. Autoimmune encephalopathies, after all, are still believed to be quite rare, but anything that helps explain central nervous system disorders that have defied comprehension is of obvious interest. That the medical community can move so quickly when it feels it’s onto something is encouraging as well.

- Next Up – Health Rising takes a deeper look at new world of autoimmune central nervous system disorders and Dr. Dalmau’s continuing work.

Thank goodness one doctor finally had the knowledge to help her. This article illustrates all over again how so many doctors, when faced with symptoms they don’t understand, either call the person crazy or give stupid advice( stop drinking, when she wasn’t) . There’s a strong need for a computerized data system that doctors can use to plug in symptoms and have a variety of diagnoses to consider…if they would use it.

Indeed, in the first neurologists defense a bit – Susannah later met a women in the epileptic ward suffering from seizures and other problems because of alcoholism – so it can happen. The neurologist clearly leapt to a conclusion – based on little evidence – and then stuck with it despite her continuing to get worse over time.

If these cases offer an indication that neuro-inflammation may be a component of ME/CFS, does it explain how exercise/physical exertion directly causes a worsening of symptoms? And does it lead to any good guesses as to types of treatment that might lesson that effect? Anyone?

Greg,

It’s quite clear that something is wrong with the vast numbers who claim CFS and FM, but it’s not what you’d think. It’s such a widely claimed “disease” that nearly all people will have some of the symptoms, and it’s very abused. Fat-assed and lazy people are the prime culprits here.

why has my rhuematologist NOT referred me to a nuerologist for my “fibromyalgia” and chronic fatigue? it is hard for me to believe that there is nothing more to be found; this is a disorder that has very very hidden causes and i guess most of us aren’t worth the ‘cost;’ and so many of us just don’t have the energy anymore for dr appts or the costly co pays these tests cost; she-susannah had a support system and obviously good benefits and/or money

My daughter has Lyme and bartonella after being diagnosed with “fibromyalgia” . Do not give up traditional Lyme testing doesn’t work you must go deeper with a lyme doctor.

All women sufferers? Odd.

It’s another autoimmune disorder that primarily affects women.

NMDA encephalitis does affect females much more often than males. We have diagnosed and treated a number of people with this disease over the past few years. The first one I recall was a young woman who, like the case you described, developed paranoid delusions and severe memory loss, and was admitted to the hospital psychiatric unit. While she had no clinical seizures, I read her EEG study and found frequent ‘silent’ seizure activity. This disease is often triggered by the immune system attacking a particular type of tumor, a teratoma of the ovary (which cross-reacts with brain tissue), which is what this patient ended up having. Removing the tumor often leads to recovery from the encephalitis. In neurology, we do often see psychiatric disorders that are masquerading as neurological ones, but also, like this, can find people with what appear to be primarily psychiatric symptoms, that are being caused by organic disorders that need to be discovered and treated. It makes for a challenging and fascinating relationship, and so rewarding when someone like this can be brought back to being them self again!

the basic pathology of me/cfs is neuroinflammation

look at the study at http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4129915/figure/F2/

Does this suggest that some neuroinflammation starts in the sinus cavities? My first chronic problem was seasonal allergies 35 years ago. Then I developed fibromyalgia, then a few years later rheumatoid arthritis and a decade after that cfs. I’ve always thought they were connected.

Trends Neurosci. 2009 September ; 32(9): 506–516. doi:10.1016/j.tins.2009.05.009

IF YOU LOOK AT THIS STUDY,CYTOKINE PRODUCED IN SIDE OF THE MICROVASCULAR SYSTEM:TNF-ALFA,IL-1BETA,IL-6–ALL LIKEY TO EXPLAIN YOUR RHEUMATOID ARTHRITIS,FIBROMYALGIA.

port of entry of pm.2.5 and UFP is nose and throat. it is so natural you will have sinus infections and allergy problem. then the pm2.5 travel through olfactory nerve–all the way to the brain frontal lobe and temporal lobe–which is the most common site of neuroinflammations of cfs/me

The fact that she and others can make complete recoveries from such a debilitating and severe illness is one of the most astonishing things about the illness.

Susannah was one of the patients who did not an ovarian tumor. Interestingly, it appears that patients with ovarian tumors are less likely to relapse. Because she had no tumor Susannah is more likely to have a relapse. Nobody knows why some people relapse at some point.

You likely have lyme disease. It is often misdiagnosed as ms or fibromyalgia. Tests for lyme are typically inaccurate. You will need to find a lyme literate doctor who will se d your blood to Immunosciences Lab in CA, and do a Western Blot test. It is the only test that is accurate. Best of luck! I have lyme… but was misdiagnosed for a whole year. Now imthe bacteria is riddled in my brain..causing lots of nerve and neurological symptoms.

That is an amazing story Cort, and you write so well. Congratulations for bringing Susannah’s story to life. How wonderful that she herself has lived to tell the tale. One wonders how many other people with curable illnesses, as you say, die neglected in psychiatric institutions.

I remember with deep regret a time when I should have ‘done something’ and didn’t, or couldn’t. I was a young physiotherapist doing a locum at a public hospital in the north of England. The hospital had been a poor house, and the stigma had persisted. Standards of care were low. I was called to clear the chest of a woman in a psychiatric ward who I was told had pneumonia. I soon realised the situation was far beyond my ability to make a difference. She was extremely ill, virtually unconscious and unable to cooperate. I was baffled that there was no line in for IV antibiotics, as I would have expected from her condition. I doubt she would have been capable of taking them orally.

When I read her notes I was appalled. She was in her fifties and had been admitted a week previously after several days of personality changes and confusion. Why she was not shifted straight to a medical ward for proper diagnosis and treatment when her chest symptoms became apparent I have no idea, but I felt powerless (especially in the rigid hierarchical system of England at the time) to question the doctors. I thought of lying in wait for her family members and expressing my concerns to them, but in the end I didn’t do that either. Whether it would have made any difference if I had I will never know. I don’t know what became of her. I expect she died.

There. Off topic or only tangentially related, but it has done me good to get that down. I haven’t written about it before and rarely talk about it, but I learned a lesson and am much more inclined to fight for those who can’t protect themselves now, and of course I have had to fight for myself as well. There is a lot of injustice in the medical system.

It must have taken courage Meg to write this.

I guess anyone of us working with people experience (if not denied) situations where we know we aren’t doing the utmost to help others … And the only thing we can do to put this ‘mistake’ right is by learning from it.

Cort, your coverage of this is potentially misleading in a detrimental polarising way (either psychotic or not). You usually write brilliantly and I greatly appreciate your efforts but not this time. Some of the symptoms you described – e.g. delusions – effectively are diagnostic of a psychosis. From there doctors, even psychiatrists, take the next step of considering whether the psychosis could have an organic (disease or lesion) basis. [As a psychiatrist myself in psychotic patients I have diagnosed (often with the help of colleagues) encephalitis, brain tumours, epilepsy and more, sometimes with happy endings.] Once an organic basis has been excluded doctors only then settle on the “functional” psychoses e.g. schizophrenia, etc. If the illness is a newly discovered one that few doctors have ever heard of, is it surprising it could be missed?

The issue of medical negligence and contempt for CFS patients is a very serious one that I am vaguely thinking of writing a paper on. However, if those of us concerned about the problem misrepresent it, doing so makes it all too easy for inept doctors to respond with more contempt suggesting that we don’t know what we are talking about.

I agree that it’s not surprising that the diagnosis was missed. Actually it was surprising that it was found. I may not have brought that out clearly enough. One thing I wanted to show was how lucky she was to be in that hospital with that doctor.

It appears I missed the boat on the dangers of being in the psych ward as well. It was strongly hinted in the book by the people running the epileptic section that she might be moved to the ‘psych ward” and that was a place she didn’t want to be because she wouldn’t get the kind of attention she was getting there. It appears that that is not necessarily true and I’ll amend the blog.

I encourage you to write that paper, Chris. I personally can’t think of a group of severely ill people more unrecognized and mistreated/untreated in relation to the severity of disability than the ME/CFS crowd. And by the nature of this illness, most of us aren’t in much of a position to make much of a protest ourselves. Thanks.

Dear Dr. Cantor,

I was dx’d with CFS in 1994 and quit my nursing career in ’99. Since 2000, I’ve had 3 separate events that I can only call “psychotic breaks” but lasted less than 24 hours, one for only 4 hours and then, aside from the physical place that I found myself, e.g. the ER in 4-point restraints and then transferred to a locked psych unit for the weekend and then discharged with no medication or in an ICU being moved for the weekend to a locked psych unit and after a 15 minute session with a group of Medical College of GA psychiatrists during that time was quickly diagnosed Bipolar Type II. All of my labwork by the way was negative for any drugs or alcohol, including aspirin or ibuprofen so I mean negative when I say it. I have no idea what caused these extremely short-lived bouts of “psychosis” but I cannot deny that I was out of body and unaware of self during that period of time and have no memory whatsoever of the events during those short periods of time. I do feel that it’s somehow connected to the neuro inflammation of my CFS/ME but will never know what the bottom line is or if it will ever happen again. If nothing else, it was interesting and entertaining once the restraints were d/c’d and I was out on the locked floor entertaining myself with the other truly mentally ill patients and assisting them in my nursing and nurturing and good-natured fashion. Why these events would last for only a number of hours is truly the mysterious part of it to me; that without medical or psychiatric intervention I would become once again alert and oriented though no memory of the past event. Have you seen such before in your practice? And, guys, cut me a break on this story; it’s not one I repeat very often as it makes so little sense and I am fine thereafter except for having freaked my family and friends out. MM

Thank you for your courageous and earnest comment, Marcie. Such horrific extremes of symptoms must reveal something about the other comparatively benign, though disabling, symptoms.

There is much injustice in the disease management system. Most doctors do their best and want the best for their patients but are rarely trained in the courageously creative, out-of-the-box thinking displayed by Dr. Najar. Several years ago Dr. Mary Ackerley, a psychiatrist and the former Director of the Arizona State Homeopathy/Integrative Medicine Board (Summa Cum Laude from Johns Hopkins, mycotoxin certification by Dr. Rich Shoemaker) wrote a groundbreaking article “Brain on Fire” which became very well known. In it she succinctly described the severe behaviors from mycotoxin illness, which produces all kinds of brain and other inflammation symptoms mimicking numerous conditions, as undiagnosed syphilis does.

Mold/Lyme and other pathogenic encephalopathies can be very complex and hit hard and fast depending on patient genetic strengths and environmental exposures. We are fortunate to to have Dr. Ackerley’s earlier, easy-to-access article as a complement to Calahan’s. Dr. Mary’s article was given to Nova U’s Dr. Klimas/NEID Clinic’s Dr. Irma Rey by a patient about the same time it was published, and she has run with it so enthusiastically that patients are now able to get treatment for mold/mycotoxin illness and perhaps related conditions. Brain, gut, microglial issues, the vagus pathway, methylation genetics: The links among these and environmental factors are becoming increasingly recognized as interdependent and will likely lead to much less suffering as patients assume more agency and educate their practitioners.

I was quite encouraged that the hospital was willing to provide VERY expensive IVIG treatment based Najar’s recommendation which was based on a mildly abnormal spinal tap reading and no evidence of autoimmune disease. If he recommends it, apparently they’ll do it. That was really good to see!

I may have missed something obvious but if Dr Ackerley’s article is easily accessed, I can’t find it. Is there any chance of an easy to click link for the particularly cognitively challenged?

Becca, Cort, anybody?

Thanks – will reply separately with my strabge psychosis episodes aged 55 and 57.

Thank you.

Christine

(languishing in a county without even an infectious diseases Consultant, where the resident Neurologist is so unpleasant, nobody ever asks to see him twice and the Rheumatologist refuses to see patients with CFS/ME/Fibro)

Search the following sites: All link to her article.

http://www.paradigmchange.me/wp/fire

http://www.forums.phoenixrising.me/index.php?threads/brain-on-fire

http://www.survivingmold.com/community

I found many links to the article here in the US. It is easily accessed if enough search words are used on Google. Cognitive stuff though could make this more difficult. Search the sites when you get to them.

Never give up. Do everything you can yoga-wise and otherwise to keep all inflammation down. Prolonged mold exposure can cause psychotic episodes or worse. Never eat inflammatory foods and see the best integrative practitioner you can, even if you have to consult by phone/Skype to do it. Australia and the US have practitioners that can at least consult on the inexpensive 23andme genetics test to get you started. If the orthodox systems have failed, abused or neglected you, go over their heads and have someone who knows these ropes guide you along the way. If a daily search is necessary, so be it. That is how others have fought their way through this former quagmire. You will find people to help and sort the helpful from the unhelpful if a positive fire is in your belly. Make it happen for a start, and I think you already have.

it should be standard procedure to have an mri brain scan done and a lumbar fluid test done if a person has had fibro-pain and chronic fatigue for over several years-

please write that paper Chris Cantor

and thank you Cort for very informative articles

Only in the U.S.! If like me you have had years of chronic pain and fatigue and a rheumatologist diagnoses Fibromyalgia then that’s it, “live with it”is all you get in the UK. The NHS is a wonderful thing if you are critically ill, but if you are slowly dying like me forget it, sad but true.

I’m hoping that the new scanning techniques that can pick up neuroinflammation will find neuuroinflammation in FM and ME/CFS and they will become part of the standard testing protocols.

Amazing. She expressed the same thoughts I had, as her TED Talk was ending, about all who had suffered in history because of misdiagnosis and no known treatment/cure. I had flashbacks of “Awakenings.” Wasn’t that the same disease, with patients who survived but left in permanent catatonic states? I haven’t read through the comments yet. Someone has probably already mentioned that.

I think that was Parkinson’s Disease in Awakenings.

No, it was a Parkinson-like condition caused by a pandemic of a viral encephalitis that happened around the turn of the century called ‘encephalitis lethargica’ that damaged the main waking center of the brainstem. It has never returned.

If these protocols work for neuroinflammation of one kind, then they might work on another. I’d like to see the same successful steps tried on people with more garden variety illnesses like ME/CFS and Fibro. But maybe it takes more dramatic symptoms to summon up the more dramatic rescue techniques.

Exactly. The least harmful protocols can sometimes be applied across the board. Just check the outstanding success of LDN 4.5, a cheap orphan drug that works wonders or partial wonders for many.

All people are DNA-individualized, unique, and while many things work for a broad spectrum of people, not every approach fits everyone. People are running out of time, out of decades, to deal with this backwards-thinking, antiquated Western medical paradigm. Approaches that are more inclusive of the best of Western and Eastern work best in my experience. The best of Chinese and Ayurvedic medicine include the whole person as a unique being without the destructive and cost-prohibitive cookie-cutter approach of the dark side of Western medicine. The ancient/timeless traditions (not talking New Age here) do not punish the chronically misdiagnosed patient with possibly lifelong incarceration. Access to what produces results has often been denied, but it is not impossible. –Not even for M.E. folks.

When in college I worked in a psych ward called the “hopeless” ward; many people had been discarded by their families for minor quirks. These broken hearts became truly insane from the horrible conditions there. All conditions were thrown together and all people were drugged together past sanity. (This happens everywhere.) Only steady human contact/compassion brought anyone out of it, and that was the purpose of our class — to give beyond labeling and, frankly, the medical brainwashing and neglect that stems from that.

The first law of all healing (Hippocrates): First, do no harm. Has the old Western medical paradigm followed its prime directive?

This is so exciting Cort! I must get hold of Dr Ackerley’s paper and maybe the book.

I apologise in advance for relating this blog to myself – as I usually do -but I’m totally on my own with CFS/ME. I’ve had CFS/ME since my early 30s but had so far isolated episodes of psychosis aged 55 and 57. To be fair to the psychiatrist, I was seen by, he arranged EEG and MRI of the brain. They were both ‘normal’ but as he isn’t a neurologist and told me he was looking for a brain tumor. He probably wouldn’t have recognised much. The first episode came during a long-standing neglected (not by me) UTI and I’ve considered that infection might have been a precipitating factor.

Thank you for this post and everybody for the comments. I LOVE this blog!

Thanks Christine, one of the things that impressed me about Susannah’s case are the many different symptoms neuroinflammation can cause. It’s extraordinary what can happen when the immune system targets a part of the brain!

Is someone trying to recruit doctors Najjar and Dalmau into studying ME/CFS? We need more people like that–interested in and willing to look into something on the relative periphery of medicine–trying to help us. Who could that “someone” be to recruit them?

It would be nice. I have a feeling though that both are fully immersed in this new field they’re helping to create. You never know though. ME/CFS and FM are MYSTERIOUS central nervous system disorders at least in part.

I imagine that if the neuroinflammation studies work out – there will much more emphasis on looking for autoimmune basis for the inflammation. I can’t imagine that wouldn’t make sense to do that given the many similarities between autoimmune disorders and ME/CFS and FM.

Hi Cort,

Thanks for the immense service you are doing to the CFS/ME community keeping us apprised of the latest happenings from around the world.

I was wondering if you have plans to interview Dr. Charles Shepherd and Dr. Abhijit Chaudhuri one of these days.

With Neuroinflammation being the hot word in CFS/ME these days, I will definitely be interested in hearing more from them. Thanks.

Air Pollution: Mechanisms of Neuroinflammation & CNS Disease

Michelle L. Block1 and Lilian Calderón-Garcidueñas2,3

1 Department of Anatomy and Neurobiology, Virginia Commonwealth University Medical Campus,

Richmond, VA 23298, USA

2 Department of Biomedical and Pharmaceutical Sciences, College of Health Professions and

Biomedical Sciences, The University of Montana, Missoula, Montana, USA

3 Instituto Nacional de Pediatria, Mexico City, Mexico

Abstract

Emerging evidence implicates air pollution as a chronic source of neuroinflammation, reactive

oxygen species (ROS), and neuropathology instigating central nervous system (CNS) disease. Stroke

incidence, and Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease pathology are linked to air pollution. Recent

reports reveal that air pollution components reach the brain. Further, systemic effects known to impact

lung and cardiovascular disease also impinge upon CNS health. While mechanisms driving air

pollution-induced CNS pathology are poorly understood, new evidence suggests that activation of

microglia and changes in the blood brain barrier may be key to this process. Here, we summarize

recent findings detailing the mechanisms through which air pollution reaches the brain and activates

the resident innate immune response to become a chronic source of pro-inflammatory factors and

ROS culpable in CNS disease.

Inflammation is increasingly recognized as a causal factor in the pathology and chronic nature

of central nervous system (CNS) diseases 1. While diverse environmental factors have been

implicated in neuroinflammation leading to CNS pathology, air pollution may rank as the most

prevalent source of environmentally induced inflammation and oxidative stress 2. Traditionally

associated with increased risk for pulmonary 3 and cardiovascular disease 4, air pollution is

now also associated with diverse CNS diseases, including Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s

Disease, and stroke.

Air pollution is a multifaceted environmental toxin capable of assaulting the CNS through

diverse pathways. Until recently, the mechanisms responsible for air pollution-induced

pathology in the brain were unknown. However, despite the variable chemical and physical

characteristics of air pollution and the consequent activation of multiple pathways,

inflammation and oxidative stress are identified as common and basic mechanisms through

which air pollution causes damage 4, including CNS effects. Furthermore, while multiple cell

types in the brain respond to exposure to air pollution, new reports indicate that microglia and

brain capillaries may be critical actors responsible for cellular damage. In the following review,

we describe the complex composition of air pollution, explain current views on the multifaceted

mechanisms through which air pollution impacts the CNS, and discuss the new mechanistic

findings implicating innate immunity and chronic neuroinflammation in CNS damage induced

by air pollution.

*Corresponding Author: Block, M.L. (MBlock@vcu.edu).

NIH Public Access

Author Manuscript

Trends Neurosci. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2010 September 1.

Published in final edited form as:

I have me/cfs. I have experienced severe brain episodes when exposed to exhaust, smoke, mold, chemicals,, hot blacktop etc. I feel completely different when I stay in the clean mountain air. Not completely well but so much relief. I crave it when in the city.

Hi Cort,

I read this book when it first came out. What struck me immediately was how different her support system was from most of us and how it really made it possible for her to be diagnosed, treated and obtain so much recovery.

My general practitioner thought I was hyper anxious and put me on psychiatric drugs. My rheumatologist thought I had inflammation and FM, but treated me with standard drugs. My GYN removed an ovarian tumor. My neurologist told me I had progressive relapse/remitting MS. Scriptts told me I had hyper mobility and anemia. It wasn’t until Dr. Peterson did an LP that viral encephalitis, inflammation and white matter lesions were found. I was finally diagnosed with myalgic encephalitis, probably of several years duration and as a result I also have temporal lobe damage and several autoimmune diseases.

This isn’t just my story, I’m sure it’s one many of us can tell. Meeting that one extremely essential doctor who does think out of the box is a luck of the draw for some of us. I believe that until ME/CFS is a required part of every med school’s criteria, all inflammatory illnesses will remain a mystery for most patients. I also consider myself very lucky.

So interesting Lynda – thanks for sharing your story and as you say many peoples story – who find that right doctor.

READ THIS ARTICLE TELLING US MITOCHONDRIAL DAMAGE WHICH ESSENTIAL PART OF CFS/ME

Ultrafine Particulate Pollutants Induce Oxidative Stress and Mitochondrial

Damage

Ning Li,1,2 Constantinos Sioutas,2,3 Arthur Cho,2,4 Debra Schmitz,2,4 Chandan Misra,2,3 Joan Sempf,5

Meiying Wang,1,2 Terry Oberley,5,6 John Froines,2,7 and Andre Nel1,2

1Department of Medicine, University of California, Los Angeles, California, USA; 2The Southern California Particle Center and Supersite,

Los Angeles, California, USA; 3Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, University of Southern California, Los Angeles,

California, USA; 4Department of Molecular and Medical Pharmacology, University of California, Los Angeles, California, USA;

5Pathology Service, Veterans Administration Medical Center, Madison, Wisconsin, USA; 6Department of Pathology and Laboratory

Medicine, University of Wisconsin, Madison, Wisconsin, USA; 7Center for Occupational and Environmental Health, University of

California, Los Angeles, California, USA

Address correspondence to A. Nel, Department of

Medicine, UCLA School of Medicine, 52–175

CHS, 10833 Le Conte Avenue, Los Angeles, CA

90095 USA. Telephone: (310) 825-6620. E-mail:

anel@mednet.ucla.edu

This study was supported by the National Institute

of Environmental Health Sciences (grant RO1-

ES10553) and the Southern California Particle Center

and Supersite, funded by the U.S. Environmental

Protection Agency (STAR award R82735201) and the

California Air Resources Board (grant 98–316).

This manuscript has not been subjected to the

U.S. EPA peer and policy review.

Received 18 September 2002; accepted 16

December 2002.

The objectives of this study were to determine whether differences in the size and composition of

coarse (2.5–10 μm), fine (< 2.5 μm), and ultrafine (< 0.1 μm) particulate matter (PM) are related to

their uptake in macrophages and epithelial cells and their ability to induce oxidative stress. The

premise for this study is the increasing awareness that various PM components induce pulmonary

inflammation through the generation of oxidative stress. Coarse, fine, and ultrafine particles (UFPs)

were collected by ambient particle concentrators in the Los Angeles basin in California and used to

study their chemical composition in parallel with assays for generation of reactive oxygen species

(ROS) and ability to induce oxidative stress in macrophages and epithelial cells. UFPs were most

potent toward inducing cellular heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1) expression and depleting intracellular

glutathione. HO-1 expression, a sensitive marker for oxidative stress, is directly correlated with the

high organic carbon and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon (PAH) content of UFPs. The dithiothreitol

(DTT) assay, a quantitative measure of in vitro ROS formation, was correlated with PAH

content and HO-1 expression. UFPs also had the highest ROS activity in the DTT assay. Because

the small size of UFPs allows better tissue penetration, we used electron microscopy to study subcellular

localization. UFPs and, to a lesser extent, fine particles, localize in mitochondria, where

they induce major structural damage. This may contribute to oxidative stress. Our studies demonstrate

that the increased biological potency of UFPs is related to the content of redox cycling

organic chemicals and their ability to damage mitochondria. Key words: concentrated ambient particles,

dithiothreitol assay, heme oxygenase-1, mitochondrial damage, oxidative stress, polycyclic

aromatic hydrocarbon, ultrafine particles. Environ Health Perspect 111:455–460 (2003).

For those of you with a diagnosis of fibromyalgia, ms, lupus, rheumatoid arthritis, and many other diseases, you likely have

LYME DISEASE! MOST lyme positive patients go for long periods of time being misdiagnosed, and going without proper treatment! This has happened to EVERY Lyme positive person I know. I have been sick with Lyme Disease for 2 years. I was given other diagnoses such as migraine headaches and anxiety/pa ic attacks. They prescribed me meds for those supposed ailments.. which played no role in killing the “bacteria” that I was actually infected with. Lyme is an “infectious” disease. It is currently an epidemic, particularly in the East coast. Lyme is next to impossible to diagnose, as the traditional Lyme tests (Elisa) done by your pcp or hospital are extremely inaccurate!! My 3 tests came back with false negatives! Given the symptoms I was having, and knowing I was bitten by a deer tick, I KNEW I had Lyme Disease and wasn’t taking no for an answer. I was persistent.. and I seeked out a Lyme literate doctor (who are hard to find). He immediately started me on antibiotics, just according to my list of symptoms I brought to him. He said that he would do the traditional Lyme Disease test (Elisa)..but that it would likely come back negative because it is horribly inaccurate. He strongly urged me to have a special test done. It was called the “Western Blot”. This test was sent to the one lab that processes this test… “Immunosciences”. The Western Blot test ended up showing the levels of bacteria for not only Lyme Disease… but 4 other bacterial co-infections that I was simultaneously infected with. I happened to be bit by (and likely infected by) 2 ticks. Many people with Lyme Disease have no recollection or proof of a tick biting them. They never get the classic “bulls eye” rash.. so they are unaware of their lyme disease until it begins to show symptoms. then the fun really begins! I was one of the people who never got a bullseye rash.

But..luckily, I was fully aware of my tick bites. Ok.. so this Western Blot test is not covered on your health insurance. It cost me $600 out of pocket.. and it was worth every damn penny…as I would likely be dead today if I did not get the test done. I have been on treatment for a year..but because it was caught late, and because I have multiple co-infections, I am still very sick. I am out of my “bed ridden” condition, and I am able to work a desk job. But my quality of life is horrible. The longer you are treated for your so-called fibromyalgia or other false diagnosis, and NOT treated with antibiotics for your Lyme Disease, the worse and worse you will get, and your neurological symptoms will reach catastrophic levels…and you will perhaps die.

This is not to be taken lightly. People are dying from complications due to Lyme Disease. .such as a heart attack or stroke or pneumonia.

Their cause of death then gets documented as one of those things.. but NOT as Lyme Disease. The statistics for deaths due to Lyme Disease are also horribly inaccurate because of this. And… the CDC does not want to recognize Lyme Disease as a chronic illness. Doctors are losing their medical licenses because they are breaki g the rules with treating their Lyme patients for longer than “allowed” with antibiotics. Most of these Lyme literate doctors are breaki g the rules to help their patients…because they also had/have Lyme Disease!

It makes you an extremely compassionate person. We all know the suffering all too well. Anyway… here are a couple links… to read about lyme vs. Fibromyalgia diagnosis, and some info about the major red tape and politics behind Lyme Disease.

https://www.psychologytoday.com/blog/why-can-t-i-get-better/201312/are-your-fibromyalgia-symptoms-due-lyme-disease

http://www.healthline.com/health-news/you-do-not-have-chronic-lyme-disease-091514

Wishing you all good health, healing… and answers! ♡

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2743793/figure/F3/

if you look at this picture, all of the questions surrounding cfs/me is with air quality–pm 2.5,

UFP.

Off topic sort off

Dead link in your post: Study Suggests Mold Exposure Can Cause Severe Effects in Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS)

http://www.cortjohnson.org/blog/2013/04/13/study-suggests-mold-exposure-can-cause-severe-effect-chronic-fatigue-syndrome-finally-meet-mold-study-finds-high-rates-of-m/

Resources

Check out Eric Johnson’s story here (not)

Well at least something’s still to be found here:

http://paradigmchange.me/erik/

Same surname, are you related?

Nothing about Particulate Matter (PM) in general either, just saying. Like Tae mentions, I thought the same.

Hello my name is Alexis McGill. I am a now 35 years old survivor of this disease called Anti- NMDA Receptor Encephalitis. I had the same exact symptoms and diagnoses last year and was hospitalized and in a coma for 18 consecutive days. I did have a Teretoma tumor as well but my symptoms were 5 times worse than this case. As I began to research what wS progressively happening to me I stumbled across this movie on Netflix and I began to cry!!! I knew at that point” I wasn’t crazy”!!!!! On July 23rd of 2018 I was hospitalized. This is a real disease and it needs more attention. People are being misdiagnosed for being psychotic when they truly aren’t. I work for the Government for 8 years and progressively got worst. But I’m my case that building had a very high level of BLACK KOLD IN IT that I was breathing in EVERYDAY!!! No one would listen. My skin would peel my face and body would break out in hives every day. And no one would listen. I was DENIED REASONABLE ACCOMMODATIONS TEICE ( to be transferred to another office that wouldn’t make me sick , but NO, Denied for no reason st ALL!!!

Let me over simplify inflammation. I am not a doctor and these are just comments on how I deal with my own inflammation episodes. We live in a high tech world of stress in a high paced environment. Our bodies adapt to this environment in a form that makes our nervous system overactive or oversensitive to all types of foreign objects or work conditions (stress can be related to inflammation).

Meaning your body is under constant inflammation (or under stress) and is either already or ready to attach anything in its path, including itself. Any abnormal work conditions (work environment) or foreign objects obtained from (infections, lime, bacteria, alcohol, virus, allergies, stomach virus, mouth infection, organ infection, toe infection, head congestion, skin infection, organ infection, I can go on and on) will trigger an overreaction and place the already overactive immune system into overdrive or into a chronic inflammation state until the foreign object (or work condition) that is causing the reaction is removed. The first step is to get rid of the infection. There are many simple remedies for dealing with an overactive immune system or chronic inflammations.

This is a classic example of vaccine damage. More and more people will have this as the vaccine rate surges. Children now are required in some states to have as many as 71 vaccines by the time they are twelve years old.

Hi,

My husband is experiencing many of these symptoms. Do you have any information of doctors in Los Angeles that can help him?

is easy there is a chronic infection usually lyme or bartonella of not ebv is brutal this is not undestood and althout iknow how to heal I. m living this nightmare have recovered a bit but gotta go trough it with meas suport at home is a human brutality and toxins and imune failure recativating this bugs will keep happening specially in woman as estrogen is gonna make this immune response fail faster bastards