On the face of it, fibromyalgia (FM) and complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS) appear to be very different disorders. Both can cause severe pain, but in fibromyalgia the pain is generally widespread and less intense (relative to CRPS, anyway), and more intense and localized in CRPS.

Both can be triggered by injuries but in CRPS the area surrounding the site of the injury often turns color, starts sweating, swells, loses hair, and becomes intensely painful – so painful that in the most severe cases amputation has been done. That kind of vivid, localized, and intense response does not occur in fibromyalgia.

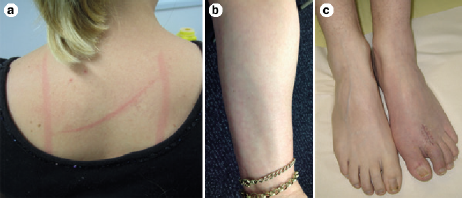

The local manifestations of complex regional pain syndrome, Is a similar process occurring in fibromyalgia?

CRPS is not always localized, though. The inflammation and/or pain present can spread to other parts of the body. Nor are visible signs of inflammation lacking in FM. People with FM can experience swelling, reddened skin, and similar symptoms.

Could these two diseases form the opposite ends of a chronic inflammatory pain spectrum? An Australian researcher, Geoffrey Littlejohn, believes yes.

Littlejohn, G. Neurogenic Inflammation in Fibromyalgia and Complex Regional Pain Syndrome. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol, 4 August 2015

Littlejohn believes one of the ties that bind the two illnesses together is central sensitization. Pain pathways in the brain and spinal cord in both disorders clearly are interpreting innocuous stimuli such as touch or movement as pain. Similar parts of the brain – the cingulate, insula, prefrontal cortex, and parietal lobe – are affected in each. Increased levels of glutamate – an excitatory neurotransmitter – and similar kinds of autonomic nervous system dysfunction are present in each as well.

Allodynia (an extreme sensitivity to touch) is often associated with fibromyalgia but Littlejohn has found that it commonly occurs in CRPS as well.

Neurogenic Inflammation

CRPS

The key to his hypothesis, however, is a particular type of inflammation called neurogenic or nerve-induced inflammation. Neurogenic inflammation was identified as early as 1910 when researchers found that removing the sensory nerves could block the inflammatory effects of mustard oil. Driven by activation of the sensory nerves neurogenic inflammation can produce a wide variety of disturbing symptoms. (One of which is the feeling of acid being placed under the skin.)

Neurogenic inflammation begins when unmyelinated C nerve fibers begin producing pro-inflammatory neuropeptides such as the substance P, VIP, and CGRP. In an attempt to speed immune factors to the site of the injury these peptides increase skin blood flows and vascular permeability. Mast cells, keratinocytes, dendritic cells, and T lymphocytes all converge on the scene. Mast cells release a large number of substances, some of which sensitize the nerve endings in the area causing them to further increase the inflammation and the pain present.

That’s all well and good in the short term. Immune factors begin healing the injury and the pain produced by substance P and other substances keeps us from using the injured area. In CRPS and perhaps fibromyalgia, though, the inflammatory process accelerates instead of being tamped down.

In CRPS the inflammatory result of the C-nerve fiber activation – the color changes, the sweating, swelling and hair loss – are stunningly visual. If CRPS proceeds, bone loss, deformity, joint problems and skin ulceration may occur. The visual aspect of CRPS makes it the easiest pain syndrome of all to diagnose.

Fibromyalgia

Fibromyalgia is often described as an “invisible illness” but Littlejohn asserts that many FM patients experience visual manifestations of neurogenic inflammation as well. Like the pain in FM, neurogenic inflammation present occurs in a more diffuse manner. Littlejohn believes it shows up in swelling, skin discoloration (livedo reticularis), dermatographia, erythema (reddened skin), cutaneous dysaesthesia, allodynia, cold-induced vasospasm, and Raynaud’s phenomenon.

Cutaneous dysaesthesia produces sensations like burning, wetness, itching, electric shock, and pins and needles. It is sometimes described as feeling as if acid was placed under the skin. The sensations can be so severe as to be incapacitating.

Dermatographia occurs when brushing the skin leaves a reddened mark. Livedo reticularis occurs as a lace-like purplish discoloration of the skin that’s often found in the lower limbs. Raynaud’s phenomenon refers to a discoloration – a whitening – of the fingers and toes.

- Let us know if you experience symptoms of neurogenic inflammation (swelling, skin discoloration (livedo reticularis), dermatographia, cutaneous dysaesthesia, allodynia, etc.) in our FM and ME/CFS neuroinflammation poll here.

While these features have not been as deeply explored in fibromyalgia as in CRPS, increased mast cell numbers in the skin of FM patients suggests neurogenic inflammation is present. The small fiber neuropathy found may be involved as well.

Central Nervous System Origin?

The signs of neurogenic inflammation in CRPS and FM may occur in the body, but Littlejohn asserts that activated astrocytes and microglial in the brain could translate into both central nervous system and peripheral inflammation.

Neuropeptide Triggers

Two neuropeptides, substance P and BDNF are markedly elevated in the brains of FM and/or CRPS patients. (Substance P is not elevated in chronic fatigue syndrome but BDNF may be).

Littlejohn proposes that elevated levels of these neuropeptides in the regions of the brain responsible for regulating emotion could explain why stress is such a common exacerbating factor in FM.

Cytokine Patterns

The C-nerve fibers, astrocytes, and microglial cells that amplify pain also produce cytokines that can sensitize neurons and affect HPA axis and sympathetic nervous system functioning. The cytokine picture in fibromyalgia is unclear but it’s clear that cytokine levels are increased early in the afflicted area in CRPS but then subside later on.

Littlejohn believes this initial period of increased immune activation produces central nervous system alterations (central sensitization) that become the dominant feature of the disease later, and ultimately drive the problems in the periphery.

A similar pattern of increased immune activation followed by a downregulation has been found by both the Lipkin/Hornig and the Dubbo teams in ME/CFS. In the Dubbo studies, Lloyd suggested that early immune activation reset the central nervous system in people who came down with ME/CFS following an infection.

Littlejohn proposes a similar process is occurring in CRPS and FM.

Spectrum Disorder(s)?

We often think of chronic fatigue syndrome and fibromyalgia as spectrum disorders with pain predominating in FM but with severe fatigue common, and fatigue predominating in ME/CFS but with pain common.

Littlejohn’s analysis suggests that FM and CRPS might be spectrum disorders as well. In both diseases, the effects of central sensitization are seen in a more widespread manner in FM and or a more localized manner in CRPS.

Update – After notching an autoimmune connection in CRPS, Goebel finds one in fibromyalgia and long COVID.

Other Neurogenic Inflammation Disorders

Many of the disorders now associated with neurogenic inflammation have not traditionally been tied to inflammation. Several so-called functional disorders that cause pain and fatigue but not the expected manifestations of tissue injury and inflammation may be “invisible” neurogenic inflammation disorders.

Migraine: Littlejohn focuses on CRPS and FM but a similar process occurs in migraine. In migraine substance P and other neuropeptides cause increased cerebral blood flows, mast cell degranulation, and the release of the pro-inflammatory factors associated with neurogenic inflammation.

The pro-inflammatory response causes the neurons in the trigeminal nerve to act up – producing the throbbing of a migraine. The nerve excitation can then spread causing allodynia in different parts of the body. Migraine, then, is a neurogenic inflammatory disorder in which the visual signs of inflammation are hidden. Many migraineurs, interestingly enough, experience an ME/CFS-like state following a migraine.

Interstitial Cystitis – Neurogenic inflammation is suspected in interstitial cystitis or painful bladder syndrome – a common comorbid condition in FM and ME/CFS. One hypothesis proposes that hyperactive C-nerve fibers and mast cell activation cause even small distensions of the bladder to produce pain in IC. The hallmarks of neurogenic inflammation process including edema, vasodilation and increased numbers of nerve fibers and mast cells have been found in the bladder tissue in IC patients. Increased levels of substance P in the nerves further suggest that a neurogenic inflammatory process is present.

Irritable Bowel Syndrome – IBS is a complex disease that features several different “sensitizing pathways” including possibly neurogenic inflammation. Further study is needed but substance P, VIP, and mast cell levels have been found to be increased in IBS.

It’s notable that the problem of painful distension crops up in several neurogenic inflammatory disorders. Distention of the blood vessels near the trigeminal nerve in migraine, distention of the bladder in interstitial cystitis/painful bladder syndrome, and distension of the gut in IBS are a cause for pain in these disorders.

Asthma – is potentially another hidden neurogenic disorder. In asthma, the immune response to an allergen or toxin appears to set the stage for the neurogenic inflammation that follows. Recent studies suggest that the bronchial spasms found in asthma are produced by hypersensitive sensory neurons in the lungs linked to the vagus nerve.

(Could a similar process be producing the shortness of breath in ME/CFS?) Van Elzakker’s vagus nerve hypothesis proposes that smoldering infections associated with the vagus nerve produce a similar process in ME/CFS.

Neurogenic inflammation; i.e. nerve induced inflammation – appears to play at least a role in many inflammatory disorders such as inflammatory bowel disease, rheumatoid arthritis, nephritis, parasitic infections or various skin disorders

Treatment

Neurogenic inflammation is generally believed to be set off by an infection or autoimmune reaction. The treatment of neurogenic inflammation, though, involves treating either a) the nervous system component of inflammation or b) attacking the consequences of neurogenic inflammation.

If FM and CRPS are both neurogenic inflammatory disorders then the treatments for both diseases will overlap – and indeed they do.

Littlejohn asserts that neuropeptides – whether occurring in the body or the brain – trigger FM and CRPS. Unfortunately, no drugs that are available now target the neuropeptides known to be upregulated in FM and CRPS.

Drugs that target “normal” types of inflammation such as TNF-a inhibitors or NSAIDS have not proven helpful in either CRPS or FM.

Drugs that reduce central nervous system activity and which target the microglia, however, such as low-dose naltrexone, ibudilast and minocycline can be successful. Drugs that target the NMDA receptors on activated microglia (ketamine) or glutamate (memantine) have shown to be helpful as well.

Because activation of the stress response system also drives some of the problems found in the periphery, stress response reducing drugs such as propranolol, phenoxybenzamine, gabapentin, and 5-hydroxytryptamine-noradrenaline reuptake inhibitors might be helpful. Using mind/body techniques to reduce the stress response may be helpful as well.

Littlejohn does not mention them but botox and capsaicin-containing creams may be helpful in reducing the pain of neurogenic inflammation occurring near the skin.

Littlejohn also does not mention magnesium deficiency but a few studies suggest magnesium deficiency may be able to cause neurogenic inflammation as well. In a rat model, reduced magnesium levels triggered the production of substance P and other neuropeptides which, in turn, triggered the release of histamine and other substances. The study suggested that even mildly low magnesium levels may be able to trigger neurogenic inflammation. (An upcoming blog will indicate that magnesium deficiency can be associated with Epstein-barr virus activation.)

Conclusion

Littlejohn believes that the processes of central sensitization and neurogenic inflammation are both at play in CRPS and fibromyalgia. It should be noted that neurogenic inflammation; i.e. sensory nerve-induced inflammation – is not always visible. Other disorders with a neurogenic inflammation component include migraine, interstitial cystitis, asthma, and IBS.

The treatment of the neuro-immune inflammation in these disorders primarily involves reducing the abnormal nerve activation that triggers the inflammatory response. A variety of drugs that reduce central nervous system activation or sympathetic nervous system activity may be helpful. Mind/body practices may be helpful as well.

- Let us know if you experience symptoms of neurogenic inflammation (swelling, skin discoloration (livedo reticularis), dermatographia, cutaneous dysaesthesia, allodynia, etc.) in our FM and ME/CFS neuroinflammation poll here.

Can sooooooooo relate to many of these symptoms

I have the three of them! ME/CFS + Fibromyalgia + CRPS in my left hand.

I had the ME/CFS + Fibromyalgia (1996) before I developed the CRPS following a hand injury in 2003.

I knew that there was a connection, and figured that I was more prone to the CRPS due to having ME/CFS + Fibromyalgia.

And when I am feeling manky (ME/CFS) my hand turns purple.

I, too, have all 3 tho mine started with crps from a severe foot injury. My foot and lower leg was discoloured for 7 years, changing gradually from black/blue to pale blue/grey. Now (19 yrs later) it occasionally gets red.

Thanks Cort, for this attention to CRPS!

Has your CRPS remained stable over time? How is it doing?

Sandra How were you treated?

Interesting connection. Charlie Rose often got together his round table of the big players in the pain industry (mostly scholars talking about the relationship between the brain and pain), and of of the docs brought on a patient who had Complex Regional Pain Syndrome. It was interesting hearing all of these docs talk about the brain in relations to pain.

This particular patient hand an injury in her forearm and couldn’t get rid of the pain after the injury had healed. I was riveted as they discussed CRPS. The thought also crossed my mind that someday, there may be a “round table” of experts explaining Fibromyalgia and how wonderful that day would be.

Thanks Cort for presenting this material.

I hope that you’re right. They certainly should – it affects over 10 million people after all.

Good for Charlie! I had no idea he did stuff like that. ..

I couldn’t figure out where to post this but before I lose this free download link that may be of interest to the crew here, here it is…

http://www.nap.edu/download.php?record_id=21767

Greetings:

I am glad to see that Cort has some help now. I was diagnosed with FM in 92 by the VA during a medical exam for something else. Even though they made the diagnoses it still took almost six years for them to finally accept the diagnoses and rate me with a disability from it.

I have a number of different disabilities that have all been declared service connect but I believe that FM has caused me more pain and frustration than anything I have ever had.

It has gradually increased in pain levels and I am able to relate too many of the symptoms described in your articles. I currently am experiencing hot burning pins and nettles in both feet, mostly the left in the first three toes counting from the little toe. The right foot gets the same symptoms but more focused in the ball of my foot pad. Both cause me to limp though the left is more prominent and when in full activation I cannot move or touch it, as if I had gout but I have had all the test and everything always comes out okay.

To add insult to injury I have been diagnosed with 100% disabling PTSD. I do have all the symptoms for it and unfortunately I have to accept the diagnoses but I know that FM and other neurological symptoms are a serious result of the PTSD or the PTSD was actually brought about by the things I have gone through with FM.

I gave up some time ago trying to talk to the Doctors about it because I can honestly see their eyes go blank and they get this look that here’s another one with mental issues trying to blame it on FM. I lost my wife to divorce because of my disabilities because she didn’t want to deal with a sick old man. I really don’t blame her I was quite the case for awhile and went through a terrible time with my grown children who were convinced that I was “doped up” and on “Speed” and other addicting drugs.

It was sad to see them have those opinions and it has taken me a long time to try and gain their confidence again. I was in deep depression from the loss of my two sisters and brother and father all within a two year period. My wife was calling me crazy at the time and a variety of other adjectives that I will not bother to repeat here.

During this time I started have pain in my neck and was getting dizzy and began having difficulty communicating and I went from being able to type at 100 wpm to about 5.

Finally I got in to see a pain specialist with the help of a super nurse. The subsequent MRI revealed serious issues with my neck vertebrae. In 2010 I went in for surgery and had fusion performed at C5-6, C6-7 Anterior Cervical Discectomy fusion with plates and the removal of numerous spurs from the area of the surgery. This was later described to me as so many spurs we lost count of how many were remove.

After the surgery I was released the next day and was surprised at how quickly I healed. Two week follow up with the surgeon I was told that my neck was in terrible shape and I should expect future problems. Those words proved to be very true.

In 2013, I began experiencing pain again in my neck but with much more related symptoms while experiencing an increase in my restless legs symptoms that became so bad I began going without sleep for days at a time.

Finally after a great deal of effort I got to see the pain specialist again. I would not even go to the VA because of their constant negative responses to my request. The pain specialist had another MRI done and the recommendation was that I be referred to a neurological surgeon as soon as possible.

Within two weeks I was in his office with a recommendation for surgery as soon as they could get me in because of the look of my spine. I might comment here that my symptoms were much worse this time. Apparently I was told that I was getting extremely angry over family issues and during this I ended up falling over the couch and one of my sons had to hold me down until I calmed down. I could not recall any of this happening.

I was falling a lot and every time I would look up and extend my neck to an exaggerated position causing the vertebra to impinge upon the nerves that were already under pressure from the bones having no cushion between the neck vertebras, I would pass out and fall to the ground.

Finally I got to my scheduled surgery and I was praying that this might fix some of the symptoms that I had from FM. After a long time in surgery I was kept at the hospital for two days because of the degree of work that had to be performed. The surgeon, a man whom I developed great admiration for from the little bit of work and coordination I was able to see before I went out.

Afterwards he explained to me that my neck was the worse he had ever seen and that I was very fortunate I got in before I was paralyzed from the condition of my spine. He explained that all the way from C-2 to 7 was bone on bone and there was virtually no cushion between my vertebra and the disk were in such bad shape it was hard to find a place to secure the plates. He had to remove the work done in the previous surgery and fuse the entire area as well as replace disk material.

He informed me that my neck did not appear to be from natural deterioration but rather from a combination of repeated injuries I had sustained and that he even found one of the vertebra that had a minor fracture in it that appeared old but he was surprised that I had managed to survive all of the injuries without being in so much pain that I would have gotten someone to look at it.

I told him then that I was so use to FM pain that I had just considered it another element of that. I have healed well since the surgery, it did relieve many of my neck pains and before the surgery I could not get my arms up over my shoulders, that has been relieved and within days I was lifting my arms all the way up.

I apologize for the length of my message, but my point was that anyone with FM or the related disorders need to be very careful that they don’t take pain for granted. It may or may not be caused by FM and all pain symptoms need to be checked closely and if you’re not satisfied with what you’re told, go ask someone else because even today there are many doctors out there who seem to take FM for granted. Believe me if it had not been for a caring nurse in my case I might have been paralyzed for life or dead.

My FM unfortunately was not relieved in anyway, obviously it was not related to my neck. I am having some terrible times with it now but I am seeing a good pain specialist who I am sure will find some way to give me some relief. Thank you so much Cort for your work with this newsletter.

It was from what I read in here that I was able to describe the relation between the stretching of the nerves in my feet, primarily toes as I climb a ladder or get on my knees with my toes curled under my feet for support as I do some minor work at home and the subsequent related severe pain I get from such activities. The doctor seemed impressed and said she would have to look into that a little closer.

Sincerely,

Jim Fields

Eugene, Oregon

Boy, Jim – you have really been through it! Thanks for your warning. I know someone who went much the same thing you did: she had neck pain that she ascribed to FM but which actually needed surgery.

Good luck with the FM pain 🙂

CRPS and POTS are both currently being investigated by the European Medicines Agency in relation to the HPV vaccines. This safety review was initiated by Danish health agencies after an ‘influx’ of teenage girls were found to have developed autonomic nervous system problems following their HPV vaccination. The Danish team of researchers have not confirmed a causal effect but they have commented in their papers that the girls all presented with a similar constellation of symptoms that didn’t accurately meet a current diagnostic entity, although they have speculated the symptom cluster had an overlap with ME/CFS, Fibromyalgia, POTS, CRPS and orthostatic intolerance was prevalent amongst the girls.

I do find it incredible that researchers look at these conditions and often discuss infection and injury as triggers and causes but invariably refuse to acknowledge, or even consider vaccination as a factor in the ‘mix’. Undertaking research into why some people develop these conditions after vaccination would surely provide valuable information for the bigger picture but this will never be done properly because of the widespread denial surrounding vaccine reactions and the refusal of researchers to be ‘tarnished’ with a reputation of fuelling ‘anti-vax scaremongering’.

Interesting….if they do find a correlation you would think it could illuminate what’s going on in CRPS and FM. Thanks for passing that on. We had a blog on this earlier – http://www.cortjohnson.org/blog/2015/07/01/the-hpv-vaccine-pots-and-mecfs-and-fm-is-there-an-issue/

It seems that the HPV vaccine has been very bad for users. It seemed they rushed the approval through at the FDA and I have wondered about this since.

Interesting – some really good CRPS studies on various autoantibody targets in that syndrome although how an autoantibody disease could be restricted to one specific limb is hard to get one’s head around.

Small Fiber Neuropathy in Sarcoidosis does actually respond to TNF alpha inhibitors like remicide – and if one were too accept that Fibro was a manifestation of SFN then in some it may also respond to TNF inhibition. Studies on this are quite limited.

I think you meant Remicade.

This explains why my legs and feet are covered in a red rash. They look exactly like the photo above. I don’t have a single, localized pain area as one would expect in RSD (Reflex Sympathetic Dystrophy, the old name for type-1 CRPS). My FM is off-the-charts bad. So is the FM and it’s close relationship to CRPS that is causing this rash?

Hello from the UK

The country backward in CRPS although to be fair Dr Andreas Goebels is doing so much for us CRPS sufferers, he is working tirelessly to find more ways to treat CRPS. I’m a long term sufferer diagnosed in 2007 but had it since 2002 after an arthroscopy.(that’s the only thing that happened)

Not long after being diagnosed CRPS I was told I had Fibro.

I have always thought there is a very fine line between the two and in UK the same needs are used for both, the spin offs that come with these conditions are random not everyone has the same, it’s only been recently that in talking to FB groups that these spots that look like bites are being discussed and our friends over the pond have said its to do with the histamine that the CRPS produces WHY?

Thanks for sharing this information. Funny, I was diagnosed with Interstitial Cystitis in 1994, F.M. in 2000 and in 2010 after a cement-less knee replacement, I was diagnosed as having CRPS Type 2 after suffering sciatic, femoral and peripheral nerve damage. My leg is is a permanent bent position and I use a cane finally and that is a big accomplishment. I have experienced many forms of pain and too be honest the exhaustion from all of these does take a toll on the body and some days are rough but overall, I find that over the years somehow I’ve managed to adjust and in fact take better care of myself and that has been a blessing.

I found this link while I was looking for answers to why I have both CRPS and FM- I had wondered if it may have to do with a severe Silicone breast implant leak, since I was diagnosed with FM shortly after the leak, and then years later, had a surgery to the hand- which developed CRPS. Now, they want to do another surgery, and I’m afraid I’ll get the terrible symptoms affiliated with CRPS/RDS worse after surgery. Such a difficult decision, but they THINK maybe I’ll regain some better use of my hand with another surgery- but what is worse? the possibility of CRPS symptoms setting in and not getting better, or my hand not getting better…

Hi I found this site when looking to see if there is a link between FM which I have had for over 22 years and CRPS which I developed in Aug 2018 following a fall and a broken arm.

A month ago I fell down the stairs and sprained a leg but since then areas of areas of FM are worse and the pain is uncontrollable. I don’t know what to do and I am not sure the local pain clinic sending me to the gym helps at all. My family never read up about FM and have no wish to read up about CRPS. I feel so alone

Hello Gail, Your response really made me want to reach out to you. The pain clinic you were sent to appears to be heartless. Please try others until you find one who actually cares about patients who suffer from FM and CRPS pain. Perhaps there is a teaching hospital in your area. Also please do not exercise without professional physical therapy help as you can make things even worse. Those of us who have FM, CRPS or both have all felt the pain of feeling alone. I am so sorry honey. I wish I could give you the big hug you deserve. As a christian I will be praying that you can get the encouragement that you so greatly need when having these conditions.

Interesting article. I have fibromyalgia, all the classic symptoms. I am also on my second bout of CRPS in my hand after a trapeziectomy for arthritis. I am 49 year old female. I first developed CRPS 2 years ago after carpal tunnel release, it was horrendous but with time and physio it improved. I have it again now but not as severe as last time. I did wonder if there was a link to my fibro.

There is a man named Anthony William that has had a lot of success helping people with these incurable chronic inflammation symptoms. I believe one of his books is called “ Medical Medium: Secrets Behind Chronic and Mystery Illness and How to Finally Heal (Revised and Expanded Edition). Hope this helps:-)