A Different Era

HIV/AIDS was the leading cause of death for U.S. adults between the ages of 25 and 44 in the 1980’s. A world-wide menace, there seemed to be no stopping the epidemic. Act Up was redefining health care advocacy and activists were marching in the streets.

That was one successful advocacy movement. A new focus on factoring “burden of illness” into disease funding priorities suggests, however, that HIV/AIDS long day in the sun at the NIH will be coming to an end.

It couldn’t come too soon for advocates for many diseases including chronic fatigue syndrome. Jocelyn Kaiser recently broke down the NIH and HIV/AIDS funding scenario in a Science article “What Does a Disease Deserve?“.

HIV/AIDS Funding in the Cross-Hairs

HIV/AIDS still does kill 7,000 people in the U.S. and many, many more around the world. A vaccine – which may finally be within reach – would be a huge deal.

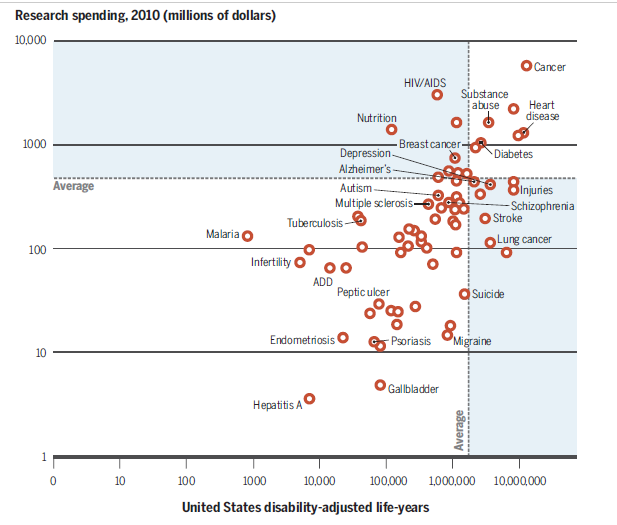

HIV/AIDS does not, however, impose a particularly high burden of illness on society. An NIH report published this summer examining years lost due to disability or death found that schizophrenia, breast cancer, stroke, lung cancer, heart disease, diabetes, substance abuse, depression and migraine all inflict higher burdens of illness on the US than HIV/AIDS. None of those disorders come close to receiving similar funding.

Heart disease causes ten times more damage than HIV/AIDS yet receives 100 times less funding per heart disease death, than HIV/AIDS does for every HIV/AIDS death.

The Disease Burden Debate

The question is not whether HIV/AIDS is getting a disproportionate share of funding. The question is why it has taken so long for this to become a real issue. Question whether the NIH was taking disease burden into account sufficiently when it was distributing its funding dates back to the 1990’s. In the past five years, though, thanks in part to Bill Gates, disease burden has become an increasingly important topic.

Gates – the biggest philanthropist in the world – wants his money to make the most difference it can. To that end he’s funded ground-breaking work by the Institute for Health Metrics lead by Dr. Christopher Murray. The Institute has found that many of the world’s medical dollars are not being spent on the medical issues that are causing the most damage. Gates uses disability-adjusted life years (Daly’s) to determine where to direct his health funding. Daly’s refer to the aggregate number of years lost to premature mortality and years lost to disability –

Migraine, for instance, produces more years lost to mortality and disability (more Daly’s) than HIV/AIDS in the U.S. yet receives a fraction of the support that HIV/AIDS does. (Twenty-one million dollars – $3 billion/year).

The disproportionate levels of funding that HIV/AIDS gets have so rankled some that an unusual effort to transfer several hundred million dollars directly out of HIV/AIDS and into the study of neurodegenerative diseases occurred during Senate Appropriations. The effort failed but it was notable for its bluntness; advocacy efforts rarely if ever target other diseases to fill their coffers.

Reports Lay Foundation For Change

NIH director Francis Collins clearly thinks enough has been enough. Last year he ordered a major review of HIV/AIDS funding. The review suggested, not surprisingly, that a great deal of fat existed in the HIV/AIDS program.

It appeared that Institute directors bent over backwards to find ways to fund their share of HIV/AIDS research. The National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (NLBI), for instance, funded 42% of HIV/AIDS grant applications but only 18% of other disease applications. That suggested that poor HIV/AIDS grant applications were getting funding while better applications for other diseases were not.

The report also found that 15% of NIH-funded HIV/AIDS research didn’t even mention HIV/AIDS in the title or abstract of the grant. That’s $450 million of research the NIH probably wouldn’t be funding if it were not for the automatic 10% funding rule. The National Institute of Mental Health was spending about as much on an infectious disease – HIV/AIDS – as it was spending on anxiety and schizophrenia.

Once the report was in, Collins instituted new priorities for HIV/AIDS funding: vaccines and treatments are now given the highest priority while behavioral and epidemiological studies receive the lowest priority.

Some of the studies that came up under a search for HIV/AIDS and behavior included:

- Strategies to optimize art services for maternal and child health – $1,000,000

- Improving health outcomes for orphans by preventing HIV/STD risk – $400,000

- Nurse delivered CBT for depression-adherence in HIV primary care in South Africa – $600,000

In October Collins told Congress that HIV/AIDS will not get its automatic ten percent cut of any boost in funding for 2016.

Collin’s statement is more significant for what it means for the future than for 2016. The NIH is still asking for a hundred million dollar increase in HIV/AIDS funding for 2016 ($3.1 billion dollars).

Collins has said he wants to move aggressively on ME/CFS funding. The 2016 budget proposal was submitted in April – long before Collins committed to increasing funding. Collins has intimated, though, that new funding could be found if Congress increases total NIH funding.

Collins appears to be getting his wish. Kaiser recently reported that the Senate, House and President are all on board with adding significant dollars to the NIH’s budget. Still in negotiations, the Senate and House Appropriations committees are adding between $1-2 billion dollars to the NIH’s funding request. With HIV/AIDS not taking it’s traditional cut more money will be available to other diseases including ME/CFS.

It looks like funding for Alzheimer’s research will increase by 30-50%. The new brain research initiative is another big winner with $100 million dollars going to that. Those two increases alone will eat up about $500 million dollars.

Collins appears to have the opportunity to keep his word to significantly increase ME/CFS funding…

More importantly, the HIV/AIDS and disease burden reports and hopefully the new strategic guidelines will lay the groundwork for more dispersion of funds to other diseases in future years. Given HIV/AIDS huge budget, even small reductions in its funding percentage-wise, could reap major dividends for other diseases. A ten percent cut would free up $300 million dollars; a twenty percent cutback $600 million.

Advocates of the status quo suggest that shifting dollars into other diseases can lead to waste if a critical mass of researchers are not available, or if the field lacks promising research avenues. That’s the kind of circular, catch-22 type argument that’s been hampering ME/CFS research for years. The NIH has used the lack of good grant applications as a reason for not funding more ME/CFS research.

Disease burden advocates assert that promising research avenues are simply a function of funding. If you don’t fund an area you won’t get promising research avenues; if you do fund it you’ll get them.

The history of autism funding suggests they’re right. After being pushed by autism advocates, autism funding soared and the quality of the grant applications improved.

New Strategic Plan Due

In the April budget request for 2016 Collins told the Senate that the NIH was developing an overarching strategic plan.

To support this focus on priority setting, we are developing an overarching NIH strategic plan, and will be linking this with individual Institute/Center (IC) strategic plans that reflect the rapid current progress in bioscience. We are also working to optimize the peer review process to enhance diversity, fairness, and the rigor and reproducibility of NIH-supported science. Francis Collins

In October, Collins stated the new plan will take disease burden into account. (The fact that this was a noteworthy statement suggests how little attention the NIH has paid to disease burden thus far.) That plan is due out this month.

Collins appears to be pushing for big changes in the way the NIH prioritizes research. Will ME/CFS and FM benefit?

The big question for ME/CFS is whether the strategic plan will give more emphasis to diseases like ME/CFS, FM, and migraine that cause lots of disability but few deaths and have been stuck at the bottom of the NIH funding barrel for decades. Will chronic illnesses that cause high disease burdens but do not necessarily kill, finally get their due?

The fight for funding will surely be intense. Whether small diseases like ME/CFS and fibromyalgia will benefit from the funding that drops out of the HIV/AIDS kitty is not clear. ME/CFS is certainly no stranger to lost funding opportunities. It was one of the few diseases whose funding dropped when the NIH’s funding doubled about 15 years ago.

ME/CFS advocacy has improved greatly, but it has a lot of ground to make up. We saw how far our advocacy efforts had lapsed when the CDC’s chronic fatigue syndrome appropriation was zeroed out simply because nobody knew to fight for it. That was a learning lesson that will not be forgotten anytime soon, and more advocacy efforts are underway than ever before.

Francis Collins has said, though, that the NIH is committed to substantially increasing ME/CFS funding. He wants the ME/CFS community to consider the NIH a friend. Just watch us he said. As the new NIH strategic overview comes out, we certainly will.

Last Day of Health Rising’s Funding Drive! The response has been great and we are just about three $5 monthly recurring donators from meeting our goal. Help make this drive a complete success and support us. Find out more here.

Although we are mostly not dying from ME, we are causing huge financial losses to: employers-due to lost manpower, sick days and short term disability, to employment insurance-where in Canada it kicks in aftershort -term disability has ended, that is if a person works at a place it’s offered.It has a set amount of about $1200 net/month-not a liveable wage.

Then comes the wait for long term disability which can takes months or years to solve-I spent all my savings and cashed in all RRSP’s to meet my obligations of a single mom of 3 with no other assistance.

Now it’s a loss to the insurance company and still to me as it’s no where near what my salary as a Nursing Director would be.

Now there is (another) desperate shortage of speciality trained nurses in Canada-gee if you had all the nurses who are on disability for chronic pain cured well then there may not be such a crisis.

The cost to society of anyone being disabled and unable to work is huge. Billions of dollars. The majority of us would rather work and contribute to society and community

Take that to large companies, insurance providers, the government (duh-they will never “get it” that preventative medicine of all sorts including treatments or cures costs the government less in the long-run and spurs the economy if more are earning a liveable wage and not on disability). Now I know it’s like talking to the wind when it comes to health care and the government. I sure hope Mr. (Dr.?) Collins puts his money where his mouth is!