Chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS) and fibromyalgia (FM) have a long, long way to go before they get the attention and resources they deserve. It would take a heroic leap to quickly achieve what people with these diseases deserve and what the diseases themselves – given their economic costs / burdens they impose – should receive. So much needs to be done (funding, doctor education, drugs, other treatments) – and we’re coming from such a low place – that it seems almost impossible that it can be done in a reasonable amount of time.

In fact, people do the impossible – make what seems at first to be inconceivable differences in one area or another – all the time. This blog is about a man who did that, and did so in a way that may directly help those with chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS) and fibromyalgia.

“Epic Measures: One Doctor. Seven Billion Patients” by Jeremy N Smith is about a man, Chris Murray, with an impossible goal – to accurately chart the health issues facing everyone on the planet. Murray has tried – and is succeeding – in doing what ME/CFS and FM advocates are trying to do on a smaller scale – to bring the true burden of illness out of the fog of incomplete, inaccurate and confusing statistics.

In doing so he’s created one of the largest scientific projects ever. It’s on the scale of the Human Genome project. He’s also a fascinating character. Confident, blunt, unbelievably hard-working, precise, committed, smart, collaborative, far-thinking. Murray both inspires and ruffles feathers where-ever he goes. It’s Murray that had the audacity to ranked the mighty, unbelievably expensive U.S. healthcare system 37th in the world.

Murray’s story of his struggle to identify and combat the immense and then largely unknown health inequities in the world will surely resonate with fibromyalgia and chronic fatigue syndrome patients.

To say that Murray grew up in an unusual family would be understating things. His father – a cardiologist, and his mother – a microbiologist – got bitten by the travel bug early. By the time Murray was 15 he’d been all over the western United States, Thailand, Turkey, Lebanon, Egypt, India, Kenya, Tanzania, Uganda, and Afghanistan, and spent, all told, over a year helping his parents and siblings treat gangrene, anthrax, guinea worm infections, malnutrition, tuberculosis, malaria and more. At 17 he was at Harvard studying under E. O. Wilson. He spent his junior year in Tunisia.

Murray was and is a force. Preternaturally smart and confident, Murray’s main asset was and probably is his willingness to embrace large goals and his unswerving dedication to them. Exposed early to the horrors of medically deprived poor people in developing countries, Murray was bound and determined to something about that.

His undergraduate thesis involved how to make the whole world healthier. He began studying international economics to understand how money was allocated to improve health.

The first bump in the road came quickly. Child death, child illness, and overall mortality figures – none of them added up. UN and World Health Organization (WHO) figures indicated that more children were dying every year from common childhood diseases then were dying in total. Some international health statistics cited seemed to be figments of officials’ imaginations. Life expectancy rates in countries could drop or climb enormously from one year to the next. At some point the UN decided that every county in the world would experience an increase of 2-4 years in life expectancy every five years, and simply tacked that number on to their estimates.

These mismatches bothered few at the WHO or UN who where happy to use whatever figures best promoted their projects, but it bugged the heck out of Murray. Railing both in print and in private against the use of made up numbers to assess health needs and funding, he became a pain in the butt at WHO headquarters.

With a degree in International Health Economics under his belt, Murray dug into the gap between health needs and funding. Murray’s first big finding came with his discovery of the 10/90 gap which indicated that 90% of the people with health needs (all found in the developing world) got less than 10% of health funding. (It was actually more like 5/95). That finding resonated, triggering hundreds of papers and dozens of conferences.

Murray next identified tuberculosis (TB) as the single most deadly pathogen on the planet. Despite the fact that TB killed almost 3 million people a year – almost all of them in the developing countries – the World Health Organization had one person working on it. Amazingly, TB was one of the easiest and cheapest diseases to treat if caught early. Vast amounts of health care dollars could be saved if early diagnosis and treatment was emphasized.

WHO had lost sight of TB for some of the same reasons that the NIH has lost sight of ME/CFS and FM. Nobody, Murray said, was standing back and looking at the big picture. Instead, TB was siloed, considered difficult to treat and sidelined. Murray’s Science article put TB back on the map. Two years later Murray was the chair of a WHO steering committee on TB, and one year later the WHO made TB control a top priority – saving an estimated 5 million lives over the next couple of decades.

Murray’s quote regarding TB applies perfectly to ME/CFS and FM’s situation at the NIH:

“If you don’t have the big picture, it’s incredibly easy for groupthink to lead you to focus on a limited number of things and you might miss what’s really important.”

The TB episode made an indelible imprint on Murray’s subsequent work. Uncovering the TB debacle was one thing but framing the information in such a way that researchers and policy makers couldn’t ignore his findings was key. From then on finding ways to effectively communicate his findings became a key goal of his.

In the 1990’s the international public health field was staggeringly primitive with almost all funds being devoted to children’s health. Murray wondered, though, about the rest of life. Adults suffered enormously from various diseases but almost no one was tracking their pain and suffering. As he walked his hospital rounds in Boston, Murray came across people who would clearly suffer from diseases for decades before they died. They were the uncounted sick.

Murray’s next job was immense – to find the way to quantify the impact ill health has (burden of disease) for every human on the planet. It was an enormous job but a necessary one. How could our health care systems provide the maximum good without knowing who to devote their resources to? In the early 1990’s a body not associated with global health – the World Bank – took Murray and his ideas on; its goal – create a World Development Report that prioritized health care needs for the entire world.

Murray took two figures – years of life lost to an early death and years of healthy life lost due to disability and mashed them together to create what would come to be a touchstone concept in public health – “disability adjusted life years” (DALYs).

By the end of 1993 Murray and his team were done. Their conclusions startled. Ninety percent of the WHO’s funding went to worthy goals (reducing communicable diseases, pregnancy, childbirth and early childhood) which accounted for less than half of the total illness burden. Many diseases and conditions that contributed to enormous unmet health needs in the developing world (injuries, depression, suicide, osteoarthritis, dental problems and heart disease) were getting no attention at all.

Murray’s findings suggested that developing countries shift their resource allocations from specialized care to low cost and effective programs on immunization, hunger relief and infectious disease control.

Advocates for neglected causes of illnesses noticed and began using Murray’s findings (particularly with regards to psychiatric diseases and musculoskeletal disorders) to lobby for increased funding. Mexico jumped on board first, sending a team to Harvard to learn how to apply Murray’s work. Their work “Health and the Economy” proved to be a landmark for Mexican healthcare. Since the 1950’s Mexico’s healthcare system had been focused on communicable diseases and pregnancy. Now the biggest health problem was unintentional injuries followed by cardiovascular disease.

Murray’s next job – at a World Health Organization under a reformer President Gro Harlem Brundtland – demonstrated what happens when an institution is unable or unwilling to accept change. Murray brought a new ethos – long working hours, a commitment to precision and efficiency – that thrilled some and horrified others who’d become used to the perks and lax work environment at the WHO.

Plus Murray wanted to up the ante considerably; no longer satisfied with describing the health problems people faced, he wanted to rank – from best to worst – how well nations were meeting those challenges.

That idea sent the bureaucrats, Murray said, “ballistic” at the anger of the countries on the low end of the scale, but Brundtland held firm. The work, which she hoped would result in massive improvements in health systems around the world, would go on. Bringing better health – not sheltering delinquent countries – was, after all, the WHO’s mandate. Murray was given the green light to bring his laser-like focus to the worlds health agencies.

Checkout times at he job went from 7pm to 10 pm – weekdays and weekends. Murray took to riding a scooter up and down his floor’s long halls to check on the work. The World Health report was released to predictable controversy on June 21, 2000. The country results turned the world health agencies on their head. The fact that France was first wasn’t so controversial, but how in the world did the U.S. drop to 37th just below Costa Rica? (It was first in health system responsiveness but 24th in healthy life expectancy and 54th in the fairness of financial contribution – a measure of how many households could not afford health care.) Colombia, now a basket case, was ranked 22nd – above Sweden and Germany. China, long thought to have a decent public health system, was 144th.

WHO’s decision-making body is made up 191 national delegates. Vehement protests followed. A independent WHO review of the document supported Murray’s findings but then Brundtland, Murray’s backer, retired and Jong-Wook Lee, a 20-year WHO veteran from South Korea took over. Lee quickly cut Murray’s staff from 22 to 2, and Murray was done. The reformer had failed.

Not all was lost. Mexico – ranked 144th – took Murray’s work to heart. Between 2004 and 2010, reasoning that it would ultimately save money by doing so, Mexico doubled its investment in health care. The number of physicians per person increased more than 50%, nurse availability by 30% and the number of people forced into bankruptcy by medical costs shrank to almost nothing. By 2012 universal health insurance was available and Mexico was redirecting it’s programs to fulfill the needs of its people.

In the U.S. resistance to any idea of national health care left it stuck where it was. The most expensive health care system in the world was 39th in infant mortality, 42nd in male mortality and 36th in life expectancy. Disparity in health care spending was one cause; the gulf between the best and worst off in the U.S. was more extreme than between Switzerland and Somalia.

Back at Harvard Murray’s needs were simple; he simply needed $100 million or so to produce an accurate assessment of the world’s true health needs. When Jim Ellison of Virgin offered to fund a $115 million project at Harvard to analyze and critique the world’s health efforts only to back away at the last minute, Murray was devastated. His dream of an independent and accurate assessment of worldwide health seemed to be over.

Enter an even wealthier man. After Bill Gates announced his retirement from Microsoft he asked a past CDC chief what to do with the almost 100 billion dollars he’d accumulated. GIven a list of 82 books to read, Gates quickly devoured 19 of them but one – Murray’s 1993 World Bank report – stood out. In fact, it changed Gates entire focus on what to do with his wealth. Flabbergasted that so many people were dying for lack of a few dollars, Gates turned to global health care and began giving away his money.

First came the 125 million dollar gift to found a child vaccine program. Gates said his hand trembled as he wrote a $750 million dollar check to support a global alliance for vaccines and immunization. (He would end up devoting several billion to the effort.) The announcement that the $16 billion dollar Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation would be using Murray’s disability-adjusted life years lost (DALYs) to assess health care needs vindicated Murray’s approach. As Warren Buffet and other billionaires joined Gates’s cause it was clear a new era in global health philanthropy had begun.

But Murray himself was floundering. Finally meeting with Gates he found another data freak with a like-minded penchant for precision and a hatred of inefficiency. The last thing Gates wanted to do was give his money away ineffectively. Murray’s pitch that an independent academic institution tracking the world’s health spending and inequities was needed worked. Gates had only one stipulation – the University of Washington in Seattle, not Harvard, would be the Institute’s home.

With that the $125 million Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME) was born. The first task was simply determining who died from what. Even in 2007 the cause of only 25% of the world’s deaths were recorded in a database the Institute had access to. Data from thousands of hospitals and clinics, health care systems, etc. had to be accessed. Plus Murray being Murray added a new twist; he determined that besides everything else the Institute was doing, it would also analyze 70 risk factors from smoking to diet to wearing seat belts for every country. Murray wouldn’t only identify health needs, he’d identify how to stop illnesses in the first place.

Almost five years, fifty full time staff and 500 co-authors later, the Global Burden analysis was complete. Almost three hundred ailments, 235 causes of death, 67 risk factors plus mortality rates, life expectancy rates, disability rates, etc. were compiled for 187 countries into a publicly available, easy to comprehend database.

In December 2012 the Burden of Health Reports from the IHME filled the largest issue of Lancet and the first issue ever devoted to one topic. The figures shocked.

In 2000, the World Bank, the WHO, the United Nations and several dozen international health organizations had agreed to focus on five health goals for the developing world: reduce child and mother mortality and stop the spread of HIV/AIDS, malaria and TB. They were worthy goals, but the Global Burden suggested that they were ignoring 70 percent of the illness burdens afflicting poor people.

Global life expectancy had increased dramatically since 1970. In fact the average global life expectancy (@70 yrs) in 2010 was equal to what was found in the best-off countries in 1979. This unexpected finding had huge implications for the world’s health care systems.

- Diseases of affluence such as heart disease, stroke and diabetes had become top killers in developing countries. That meant treatments like insulin, blood pressure medications, and chemotherapy should be on the international health donors’ lists.

- Women lived longer than men but were significantly disadvantaged with regard to disability and spent much more time in poor health.

- The things that caused disability in large part weren’t the things that people died from.

- Major depression caused more total health loss than tuberculosis.

While causes of death often varied widely from region to region the causes of disability – the stuff that made you miserable and prevented you from functioning but didn’t kill you – was consistent from country to country. Only one (anemia) was being addressed by the international health care community.

Top Ten Causes of Healthy Life Lost to Disability

- Low back pain

- Major depression

- Iron deficiency anemia

- Neck pain

- COPD (chronic obstructive pulmonary disease)

- Musculoskeletal disorders

- Anxiety

- Migraine

- Diabetes

- Falls

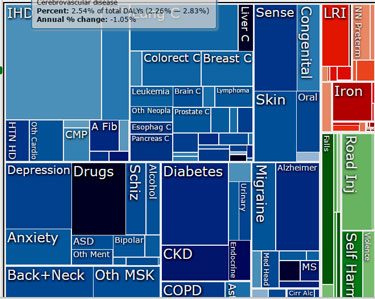

A figure which combined both years lost to disability and death from illness, disability-adjusted life years (DALY’s) revealed that diseases of affluence (heart disease, stroke) were now numbered among the world’s greatest illness burdens.

Disability Adjusted Life Years

- Heart disease

- Lower respiratory infections

- Stroke

- Diarrheal disease

- HIV/AIDS

- Low back pain

- Malaria

- Preterm birth complications

- Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)

- Road injuries

A list of the top ten risk factors revealed more changes.Being underweight had previously been a major problem but now being overweight, high blood pressure, alcohol use and high blood sugar were causing more illness. Household air pollution’s contributions to lung and heart disease, stroke and cancer indicated that bad air was far more problematic than lack of access to clean water – a major international health priority.

Differing risk factors indicated that a one size fits all approaches don’t work. Alcohol abuse contributed to a quarter of all mortality in Eastern Europe and Russia, tobacco was a major issue in Europe and North America, high blood pressure driven by high salt intake was a big deal in Asia and the Middle East, obesity and diabetes was rampant in Mexico, violence in Honduras and El Salvador. Poisoning was a real problem in Eastern Europe.

Realizing that communication was key, Murray created a visual program called GBD Compare that allowed anyone to easily understand his findings. Simply by pointing to an area of concern in a country the GBD Compare could show you the health losses from any disease at any age and gender, and the risk factors contributing to it. Digging down through GBDx Murray could show that HIV/AIDS – easily the single biggest item in the NIH’s budget – accounted for only 1.1% of years lost to early death in the U.S. Heart disease accounted for 16%. One third of the years of life lost to early death from violence in America was attributed to alcohol use.

Mental health was revealed as a huge drag on society worldwide with 40x’s the impact on disability as cancer. The three biggies for disability were mental health, musculoskeletal disorders and diabetes. The UK’s below average healthy life expectancy was attributed to poor diet, smoking and alcohol and drug use.

The Burden of Illness (BOI) report was a huge success but Murray, of course, wasn’t done. Next up was determining BOI for regions and even cities, figuring out how education level impacted health, delineating the barriers to accessing health care, analyzing the effectiveness of health care systems, tracking personal health in communities and more.

Smart, incredibly hard-working and creative and committed to making a difference, Murray has had it going on almost all levels. Deeply embedded in the academic community, he’s much more than an academic pouring out papers. For one, his vision – birthed in the devastation of the Sahara desert – to bring clarity to the entire world’s health problems was almost unthinkable. For another, early on he realized that communication and getting access to decision-makers was key.

In the end, Christopher Murray ended up achieving the impossible and in doing so revolutionized our understanding of the world’s health. Bill Gates’s help, of course, cannot be understated. Murray had the gift of good timing to be promoting his project just as the world’s wealthiest man began looking for ways to make a difference.

It was Murray’s expose of the tremendous health inequities around the world that first aroused Gates’s attention and that brings us to our own challenges. Here, surprisingly, Murray lets us down. No information on fibromyalgia or chronic fatigue syndrome that I could find exists in Murray’s worldwide database.

The issue may be lack of good data but Murray has found ways to deal with data issues before. In fact, he’s argued that incomplete data should never halt analyses or keeping health policy makers from implementing policies. Unless I’m missing something, though, Murray and the IHME are completely ignoring diseases affecting millions of people across the U.S. and accounting for many billions of dollars in economic losses a year.

That’s unfortunate but by bringing light to health inequities across the globe and by providing ways to quantify them Murray has laid the groundwork for diseases like chronic fatigue syndrome and fibromyalgia to get the resources that they need and that work has begun.

In a landmark paper Mary Dimmock and Lenny Jason have begun to fill in the gaps by extrapolating the disability-adjusted life years (DALY’s) for chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS). Their figures indicate that given the illness burden ME/CFS imposes it should be receiving many times the funding it now gets. That’s the kind of information advocates can use to get these diseases the resources they need.

A blog on that paper will be up shortly.

Looking for specialist in chronic fatigue/fibromyalgia

in CT…recommendations, please.

Thank you.

Neena241@optonline.net

There’s a Dr. Levine in NYC. Sorry don’t have anything better re: info. Also Vermont has a great state support group. Again don’t have a website but you can probably find it with Google.

Fascinating article Cort. I had just read the Dimmock and Jason paper last night and this adds a “behind the scenes” dimension to their work.

I had not heard of Christopher Murray before and all I can say is, Wow!, what an amazing person. I know I am dreaming in technicolour ( as usual) but wouldn’t it be great if he could be sent a copy of Dimmock and Jason’s paper and that he then decided to do further research on it?

What we really need to do is get Bill Gate’s attention. Perhaps this is the way to do it.

Try this database. You can search by state then city.

http://fmcfsme.com/doctor_database.php?c=United%20States&s=Connecticut#city

Kate, this list is very outdated. My first F/CFS/ME doctor, who is on that list, only practices “hormone therapy” today. Left our specialty 5+ years ago.

Very interesting, Cort. Perhaps Mary Dimmock and Lenny Jason will consider sending their paper to Christopher Murray (and Bill Gates!).

Great idea! I sent an email to IHME asking why no information on ME/CFS and FM. Haven’t heard back from them yet. Let’s get on GBD Compare.

Nice going! I hope they get back to you. Of all the places that their intervention could make a difference – which is surely what they want – this disease is surely one of them.

Exactly! Chris Murray says his goal is to define illness burden so that health resources can be directed to those who need it most. Ultimately he just wants to make the world a healthier place. How can he do that by ignoring 10-15 million Americans?

I just sent an IHME Representative this:

Please no! Dr. Lenny Jason firmly believes that all biological findings fit into the greater category of psychological for ME/CFS. At the IACFSME Professional portion of the conference, he told doctors that “by far the greatest” amount of funding goes to psych for ME/CFS, and even biological findings which lead to patients wearing heart montitors “teach the patient to pace themselves”. Anytime a psychiatrist says “pacing” they mean we are simply people who don’t know how to rest when we’re supposed to and that we have less energy, but the ONLY reason we crash is poor planning. Seriously. I’ve had several conversations with some psychiatrists who see ME/CFS patients. It’s surreal.

I’m not a doctor, scientist, researcher or psychologist. But I can tell you, I’ve lived with this for 30 years and it’s not a mental condition. It’s digestive, heart, nerve, brain, bone, muscle, simply put physical. The brain is in play in a nasty way and it needs to be looked at along with the whole body system. I’m not crazy this is real and it deserves attention not a sleu of antidepressants that create lithargey and rock hard stools. It’s real

Renee, you’re right, the brain needs to be looked at in ME/CFS and as been. The problem is that the psychiatric profession as a whole has…and yes, I’ll use this word…twisted the interpretations so as to invent patient mental problems for physical problems. The term “post exertional malaise” for example, does not inform the other medical professions about problems with the krebs cycle, the ATP cycle, the electron transport chain, methylation, lactic acidosis nor muscle twitch fibres. Malaise is indicative of a mental problem with exertion. Influential psychiatrists have been sure to get on boards and committees of governments as some sort of important stakeholders for our illness, and ruin the work of many biological researchers in the communication.

David Tuller is right when he says it’s up to us to get political. I think the first thing to do is get psychiatrists out of influential gov’t committees and orgs of a biological disease. Maybe they could be helpful, but the lot of them to date have been obfuscated when it comes to relating bio info to other doctors and are greedy for an unjustified amount of funding while presenting a concerned face IMO. There. I said it. I think this needed to be said.

I’d just like to add this is not unique to ME/CFS. The psychiatric field as a whole has a long history internationally of helping government to handle “problems”. In Switzerland, I believe being gay is still considered a mental illness. Countries that don’t have human rights will find willing psychiatrists to declare political opponents mentally unfit and strip them of further rights. In Western countries, suffragettes who protested too loud were rounded up, jailed, and underwent mandatory psychiatric evaluation, with the psychiatrists pressured to find something wrong so as to shut the protesters up. In Canada, transgender individuals must still undergo a year of mandatory psychiatric evaluation in order to be approved for surgery. Even if they’re well into middle age and it’s apparent within the first interview that they qualify. When governments opposed medical and recreational cannabis,gov’t funded psychiatrists were more than willing to accept money with the direction that they only find harms however minute, and not study the possible benefits of cannabis. They never declared this limitation on their studies to the public that I’m aware of. When you think of the kids with epilepsy that could have benefited from cannabis oil all these years, it leaves a bad taste in the mouth about the psychiatric profession as a whole.

Fascinating article. Let’s think outside our box Are you writing to Murray to inform him about me/cfs? Maybe we all should be writing him. Do you have an address for him?

I sent the IHME an email last week asking why there’s nothing on FM and ME/CFS. Maybe we should organize something (?)

Yes! We should! This page contains his phone number and email address at UW: http://globalhealth.washington.edu/faculty/christopher-murray

I wonder if we can get #meaction and Ron Davis in on this effort?

Wow! Great effort by Murray, superb article, Cort. Thank you. Lots of interesting stuff in there. On, Jason and Dimmock!

Fabulous writing Cort and fascinating information. Hope is, once again, peeking through the storm clouds!

I am encouraged that people like Christopher Murray are out there looking and seeing that there are huge health issues that exist and not understood or acknowledged. I’ve had ME/CFS for 30 years. My doctor is gone and now there is no place to go. Doctors hear my low non energetic voice as I talk and look back at me like deer in the headlights. I’m on disability and trying. I tried to work again in an easier type of job but can’t hardly stand so it ended. I had control of symptoms for quite a few years but then breast cancer treatments landed me right back into this acute hell. 30 years of reality illness with no hope and no recognition. My life is over I can’t do this anymore. Please RESEARCH! There are a lot of us out here.

Yes, Research, research, research.

I think they will find this a fascinating field! I wish I could just jam that thought into the NIH’s head. You’re going to love it when you get into it.

Renee,

Please hang in there. I know it is difficult. I understand in many ways how you are feeling. It is difficult to have any hope when it has gone on for so long without a rope to have a grip on. I am trying my best to have hope.

Renee, I think you are the first person I have noticed who has has ME/CFS as long as I have. So much of the research is targeted for those who have had it a few years. I feel like there is an expiration date…

10yrs or less. Research.

30 yrs. Oh well…

37 for me…Hard to believe!

I have had CFS since 1978. First got pericarditis and never got well. Decades spent with flu like symptoms plus many more .

I don’t get this at all. A list that has Costa Rica above the United States is maybe not a list I trust. And I guarantee you that after the Affordable Care Act most of us in the middle class are paying much more for our health care then when he created his list so I would assume that we are even lower on the list today.

I would love to hear what people outside of the U.S. have to say about how they are treated with their chronic illness of ME/CFS and or Fibromyalgia in their own countries? I haven’t heard many positive things. Some quite scary actually.

Also, the 39th in infant mortality rate is VERY misleading. The reason that number is so high is because we try to save so many premature babies. According to the CDC, “very preterm infants accounted for only 2% of births, but over one-half of all infant deaths in both 2000 and 2005.”

I think Big Data has its place. It can be used for great things. I am not sure Bill Murray is doing anything for ME/CFS. Maybe his methodologies will be of some help; but then again they could also lead to things like letting people believe the United States somehow has terrible infant mortality rates when it is quite literally the opposite.

As I started with, I think am not getting it.

Check out the latest on infant mortality rates in the U.S. The latest data suggests its actually the opposite of what was thought; the U.S. is very good at keeping preterm infants alive but lousy (comparatively) at keeping full-term infants alive.

http://www.livescience.com/47980-us-infant-mortality-full-term-babies.html

US Ranks Behind 25 Other Countries in Infant Mortality

By Rachael Rettner, Senior Writer | September 24, 2014 02:39am ET

The U.S. infant mortality rate is more than double that of some other developed countries, according to a new report.

An important contributor to this disparity is the relatively high rate of death among babies born at full term in the United States, compared with that of other countries, the report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention found.

Dr. Edward McCabe, chief medical officer of the March of Dimes, a nonprofit organization that works to prevent preterm birth, said he was surprised by this result. The findings “challenge the conventional thinking” that America’s high infant mortality rate, relative to other countries, is mainly due to high rates of preterm births in the United States, McCabe said.

The report compared the U.S. infant mortality rate with that of 28 other developed countries. The CDC defines infant mortality as the death of a baby before his or her first birthday.

In 2010, there were 6.1 deaths for every 1,000 live births in the United States, which was higher than the rates of 25 other countries in the report, including Hungary, Poland, the United Kingdom and Australia.

In the top-ranked countries, Finland and Japan, the infant mortality rate was 2.3 deaths per 1,000 live births — less than half the rate in the United States. [7 Facts About Home Births]

Despite improvements in the U.S. infant mortality rate since 2005, “This pattern of high infant mortality rates in the United States when compared with other developed countries has persisted for many years,” the researchers at the CDC’s National Center for Health Statistics wrote in the report.

In a second analysis, the researchers parsed out the infant mortality rates according to babies’ gestational age (meaning how long the baby was in the womb before birth), for the United States and 11 other European countries that had this information.

The U.S. mortality rate for infants born very early, between 24 and 27 weeks of gestation, was favorable compared with the other countries — the U.S. ranked 5th out of the 12 countries. (The researchers excluded babies born before 24 weeks of pregnancy, because not all of the countries had information about this group.)

In contrast, the U.S. infant mortality rate for babies born at 37 weeks or later (considered “full term”) was actually the highest among the 12 countries, and about twice the rates in Denmark, Finland, Norway, Sweden and Switzerland.

The reasons for the findings are not known, but the new report brings attention to the problem, McCabe said.

“People are going to want to try to get to the bottom of it and understand it better,” so that action can be taken to further reduce infant mortality, McCabe said.

An earlier analysis by the March of Dimes found that most deaths among babies born at full term were due to birth defects, sudden infant death syndrome and accidents (such as accidental drowning).

If the United States could reduce its infant mortality rate for full-term babies to match that of Sweden, the overall U.S. infant mortality rate would decline by 24 percent, to 3.2 deaths per 1,000 live births, the report said. This would mean there would be nearly 4,100 fewer infant deaths yearly.

If the United States reduced its preterm birth rate to match that of Sweden, that would mean an additional 3,200 fewer deaths.

“Such a decline would mean nearly 7,300 fewer infant deaths than actually occurred in the United States in 2010,” the researchers wrote.

Rachael Rettner, Senior Writer

Cort, are abortions included in those infant mortality rates? Sweden doesn’t allow abortions after 22 weeks.

Would be interesting if they tracked maternal meds. In Canada, prescriptions for anti-nausea meds are filled for every 2 births.

Tina

I live in New Zealand. In 1990 I found a good doctor who diagnosed me. I received sickness, then invalid benefits continuously. They provided just enough to live on in reasonable comfort. There is extra money for medical costs,lawn mowing etc. Hospital treatment is free for everyone. I an now more ill and help with housework is provided. That was not so easy to get but now if I need more help it will be provided.

Tina, Costa Rica has a very advanced and world class health care system. Have you seen the hospitals? Gorgeous. They’re environmental law is also outstanding. They stand out in their region of the world. https://internationalliving.com/countries/costa-rica/health-care/

I hope that he and others join the few that are now working so hard. I am afraid that an answer will not come in time for many of us that have been suffering for so long. Thank you Cort for this information and all your hard work.

Thank you so much for this wonderful article, Cort, and for being our voice and advocate. I think (hope) we’re on the right track.

Just for the heck of it, yesterday and today, I visited “cancer survivorship” clinics at 2 major Seattle area hospitals, both claiming to have “world class cancer centers”.

At both, I asked who could fix my CFS, triggered by my “successful” cancer treatment. (I have all the usual CFS triggers and symptoms, too, and fit all the criteria…) I brought all my weird lab work and a stack of medical research on cancer related fatigue, CFS, chlamydia pneumoniae and B12 deficiency, mitochondrial dysfunction, etc.

They hadn’t a clue.

At both, I suggested they find me an immunologist or a CFS expert.

The ARNP at Hospital #1 suggested I see a psychiatrist or find a family medicine doctor. When I suggested neither could help given the complexity of my situation, she became flustered and bolted from the room, sending a social worker to get rid of me.

The ARNP at Hospital #2 genuinely seemed curious and seemed to believe my story, but said she hadn’t seen anyone with CFS in her 35 years of practice. This hospital runs regular ads talking about their world class cancer immunotherapy capabilities. She said they had no clinical immunologists… and then referred me to a pain clinic and a psychotherapy clinic…

Cancer treatment is well known to cause long term serious fatigue, mitochondrial damage, and compromised immunity, and it is not a surprise some of us will develop full blown CFS.

The reaction I got here is not unusual. I’ve called the American Cancer Society and National Cancer Institute and CFS is not even on their radar screen. BILLIONS are being spent on trying to kill cancer, but no one seems to be researching or treating CFS caused by cancer treatment… and there are likely many thousands of us.

My thought is maybe some of the cancer largesse could be siphoned off to fight CFS…

But no one’s counting people like me… we don’t exist, unless we go get psychiatric help…

Back to the Murray article. Since I’m here in Seattle, maybe I can call him up and take him to a local Starbucks and educate him on the hidden nature of CFS. I sure feel hidden today.

lerner there are people like myself who are developing cancers from me/cfs. I have had 2 and have spread to lymphs. no question cfs is underlying illness. all cfs doctors I have seen agree with my diagnosis. that said there are some doctors like Peterson and some others that are finding cause and effect.. it is a sub group right now as far as I know but it is definitely happening amongst other secondary issues caused by cfs

Thanks for pointing out the relationship of ME/CFS and cancer, Jimmy.

I’m not as scared about getting moly first cancer back as I am about developing leukemia or lymphoma, which my parents both had.

The more research I read on CFS and cancer, I cannot see how they’re NOT related.

We hide that’s what we do because we can’t keep explaining why day after day, week after week we don’t get better and just can’t do what we would like. Leaving the house can be hard and talking with shallow breath unbearable. I wonder if people reading will try and profile me as a lazy that would rather sit, lay and eat myself into oblivion. Well, I’m opposite of that. I had a great job which I loved, I’ve been into nutrition before it became a conversation, I hiked, biked, ran road races with my dad and enjoyed my family. Never smoked, never over weight, not a drinker, just a health minded person. You are correct, we hide because there is no recognition and we get slammed into the crazy corner. I hope that you get some answers

Renee, Thank you for your kind words. I hope you do. too, and we can go back to being active again.

Learner, you have a good idea there. Ron Davis also feels that those who suffer adverse affects from clinical trials involving meds should be tracked. The results of studies are inflated positively by dropping those with the worst adverse affects who won’t even last till the end of the study. As if they never existed. Add to that the fact that half of gov’t funded studies are not published, and we see why the medical world never gets the communication that some of these drugs can have horrible effects for many more than they are being told.

Learner, Cort has an effective tool here for tracking CFS onset after cancer therapy, the forum. Have you added your story? Have you encouraged others in your boat in person and online to also add their story? I’m thinking that if everyone answers the questions to the best of their ability, and keeps their contact info current, we could lobby for a study as it will be impossible to pretend that you don’t all exist. It’s high time.

Cort, could you create a section in the forums for CFS onset after meds, with cancer therapy being a category? Could you create a template like the one for the recovery stories? Hope I’m not being too bold and asking too much!

LY,

I’d be happy to add to the forum – if you send me a link, I’ll do so.

Over the past year, I’ve collected a lot of research that says that chemotherapy damages mitochondria and suppressed immune function and creates “cancer related fatigue.”

And articles comparing long term cancer related fatigue to ME/CFS and finding they’re virtually the same. And the latest news, that oncologists should be telling patients they may never recover their lives from CRF/CFS.

None of this came up when everyone around me was telling me I was crazy if I didn’t do chemo. Even my naturopath, and he’s one of the best, thought I’d be OK.

Well, I’m not. It’s not just the chemo, of course. I had existing toxicity, lousy methylation SNPs, and a load of quietly smoldering chronic infections. The chemo was the straw that broke the camel’s back. But some of these other factors likely contributed to the development of my cancer to begin with.

Thomas Seyfried’s paper “Cancer as a Metabolic Disease” challenges modern beliefs about cancer. Solid tumors don’t have cloned cells with the sane aberrant gene copied in each. Rather, they are mosaics of differently mutated cells, pointing to a metabolic cause.

He also discusses mitochondrial and immune system dysfunction, as well as ketogenic diets starving cancer cells, with mitochondria that can’t do OXPHOS, and can only do glycolysis.

I realize the answers are likely 15 years away. But, from the comments I’ve seen, CFS patients do tend to get cancer, and cancer patients do get CFS. And both have unhappy mitochondria…

This is just a birds eye view. Digging deeper, there’s a lot more. It would be valuable to have more research in this area. There’s also a lot of money in cancer, do I’m thinking if any can be diverted to look at CFS, it would be good for everyone.

I’ve been in the weeds fighting my own battles, but am very interested in advocating for this… just not sure how to go about it.

Cort, would you need some donations in order to set up a section in the forums for Learner and other cancer treatment patients to share their stories of adverse reactions? I realize it could be under general discussion, but perhaps it deserves its own heading so that we can gather a number of cases which might lead to being able to qualify which ME/CFS patients should and shouldn’t take chemotherapy or if they absolutely need it, the precautions which should be taken.

Learner has a wealth of information re cancer and CFS/ME, and by coincidence, I came across an interesting book online tonight which blew me over considering that many of us find added choline in the diet helpful: “Choline is the only single nutrient for which dietary deficiency causes development of hepatocarcinomas in the absence of any known carcinogen.” The book goes on to say what Learner has said here, that DNA methylation changes in cancer development (attributes it to lack of choline). It calls for awareness of medical practitioners when it comes to vulnerable popultions, and more studies establishing daily requirements of choline. https://books.google.ca/books?id=S5oCjZZZ1ggC&pg=PA533&lpg=PA533&dq=total+parenteral+nutrition+methylation&source=bl&ots=2xPEvWhLxz&sig=VJylZspHyGYevlNpSpBHGD44eGY&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwi7von0osXRAhUCwYMKHWPYCOEQ6AEIKzAE#v=onepage&q=total%20parenteral%20nutrition%20methylation&f=false

Thanks, LY.

I agree about vulnerable populations…?

And this is the kind of thing that should at some point be integrated into the knowledge base, especially when so many of us are on so many methylation supplements:

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3806315/

Most of us definitely need methylation support, but it’s a warning that too much of the wrong thing can backfire. On the other hand global hypomethylation sets one up for cancer as well.

Could ME/CFS/Fibromyalgia be inaccurately hidden in the category of ‘Musculoskeletal Disorders’?

Ha! You checked it out 🙂 Good question. I asked for permission to dig deeper into the muscoskeletal disorders – you have to request that but before I got an answer back I got an answer to my earlier email. They don’t track them at all. Now I am trying to find out why. I just sent Anna a longer email asking why these diseases are not part of the database.

I just replied to Anna this

Thanks for pushing on this, Cort. Looking forward to their next reply!

Please notify me of the response to your above email. I am extremely grateful for your inspired, dedicated and honest efforts for which i have benefited greatly! Thank you and torrents of God’s graces and blessings to you and all those you hold dear.

Great article, Cort! You write superbly !! Fascinating Doctor!

Cort, when are you going to write a book on CFS ? All your experiences would make such an amazingly interesting read. It would also be very interesting to hear the stories of those of us who have been sick for 30 plus years !

I’m playing devil’s advocate on this one: I’m not surprised there’s not ME/FM info to be found. Vaccinations, organophosphates and genetically modified food which may inhibit the ability of the body to draw out the nutrition from food can all trigger our symptoms. I also have to wonder how many people developed health problems working at WHO until 10pm and on weekends. Labour rights, people!

Other views on Bill Gates and multi-vaccinations for third world countries:

http://www.globalresearch.ca/big-pharma-and-the-gates-foundation-guinea-pigs-for-the-drugmakers/5384374

https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2016/jan/15/bill-gates-rockefeller-influence-agenda-poor-nations-big-pharma-gm-hunger

As westerners become more health conscious and aware of the harms of GMOs, Autoimmune Disorders Induced by Vaccine Adjuvants, and pesticides, third world countries are being innundated. Except nowadays the same companies that make the medicines also make the pesticides too. Thanks BayerCropScience.

Just what I was thinking. Messing with nature and chemicals on the crops and in the animals, all sorts of pollution. Poisonous drugs with nasty additives like mercury and fluroride, more and more you see the load the body is having to take on. Sounds like this is deliberately being left out.

Cort, does the database contain info about Myasenthia Gravis?

If anyone’s ever had TPN, that is, nutrients by IV for a period of time, there’s an interesting study looking at peroxides contaminating the line changing DNA expression, reprogramming metabolism and not for the better. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23411941

If we can each get the Dimmock, Mirin, Jason article to are senators, congressional reps, this clearly shows gross discrimination against M.E., but lack of tracking by CDC, so thereby ME does not exist, and thereby lack of funding at NIH since we need to Act Up, not hide with M.E. in the closet. When Millions missing become visible, in front of all politicians, M.E. can no longer be ignored by just politicians. Any politicians that discriminate need to be removed from office in next elections. Making America healthier with more NIH funding incl $200M/yr for M.E., is what can “Make America Great Again”. This is a bipartisan issue and needs to be supported by 100% of elected officials, Trump, Replicans, Democrats, Independents. I attended Health Rally in San Francisco CA City Hall today with thousands of others, organized by Congress minority leader Nancy Pelosi, and met many people including those with Lyme, 3 with ME/CFS all in two hours,m and all want to end neglect of these diseases. Hope we can all work to Cure M.E., FM, Lymne and other “Forgotten Plagues” that are finally yielding to Research. Wish you all the best health possible in 2017. My 22 year old son was taken to ER again Sat, now admitted, and this happens across that country to too many, to often. Thanks Cort as always for superb articles about Christopher Murray. We all need to find ways to reach people like Gates, Zuckerberg, Brin, Sean Parker, since they may be able to make a huge difference for M.E., and perhaps make up for 3 decades of gross Federal neglect.

Mark C, thanks for advocating! Do you agree that medications have added to the toxic burden of ME/CFS’ers and we need commitments to find non-drug solutions? Many studies are only looking for a drug solution.

It’s time that studies track adverse medication effects don’t you think? In addition to healthy controls, studies should also have natural alternatives to drugs tested. This would be a game changer. It would shake up the power of Pharmaceuticals in research, but it’s time they shared the field with other less toxic solutions.

At the United Mitochondrial Disease Conference last June, Robert Naviaux spoke on cell danger response, all the things that can negatively impact mitochondria.

He was followed by Kendall Wallace who spoke about toxins getting into mitochondria, and showed graphic photos of arsenic sitting in mitochondria.Then, they described work where they’ve looked at the impact of pharmaceutical drugs on mitochondria and found that something like 75% damage mitochondria.

Naviaux got up, turned to all the doctors in the room, and gave an impassioned speech about being careful about what drugs they were prescribing for their patients so as not to cause even more damage, and to become activists at getting toxins out of our communities and out of their patients’ lives.

Well known drugs like ciprofloxacin, acyclovir, levodopa, chemo drugs, etc. cause damage to mitochondria. From what I saw, most drugs can be counterproductive in our efforts to get well, so we should proceed with great caution.

Thanks for bringing up this important issue.

Learner, something must be done!

I’ve realized that Cort’s already set up a perfect way to share your research: https://www.healthrising.org/contributing-your-content/

What would you thinking of creating a blog? I’d be happy to collaborate with ideas of how to advocate for the kinds of research / treatment protocols etc. that’s been ignored to date.

The Dimmock,Mirin,Learner study noted that skin(and other) cancers are particularly high amongst ME/CFS’ers. You’re absolutely on track! If we consider that lack of choline can contribute to cancer, I wonder if this product could help prevent cancer amongst us. And also increase acetylcholine which could potentially help the ANS. The product’s called Biosil and it’s applied topically. http://www.biosilusa.com/does-choline-provide-any-other-health-benefits/

If you contact Cort re writing a blog, please ask him for my email.

Thank you for your encouragement. LY. There are a lot of dots that need to be connected, and I’d definitely be interested in helping. I’ll try following up with Cort.

I just read the Dimmock, Mirin and Jason study and I’d like to point out that it doesn’t say that ME/CFS is NOT a disease which is caused by the patient’s inability to pace. In fact, it compares ME/CFS to other diseases where it says patients are to blame, and advocates for funding despite this. It compares ME/CFS to smoking primarily causing COPD, to liver disease caused by drinking, and suicide and eating disorders. BTW, COPD may be primarily caused by meds and environmental chemicals, but the gov’t funded studies are not published in medical journals, just on the gov’ts website.

The communication of the idea to the medical and political communities and the public that our inability to pace ourselves is the cause of ME/CFS which is the current “accepted wisdom”. We don’t need this kind of advocacy! The appropriate comparisions would have been Alzheimers, heart attacks and cancer. Those are diseases to be comparing ME/CFS to when it comes to funding. Diseases with proper rehabilitation not under the umbrella of psychiatrists.

Thank you for the comments, LY. Scientists called out those diseases in the Johnson article to make a point about the levels of funding being provided – i.e. that we tend to underfund diseases when we blame the patient. I’d say the same is true for stigmatized/contested diseases. This was not comparing the nature of ME to these diseases. The graph on disease burden versus spend instead included MS and AIDS which have similar burden but very different spend.

Thanks for your reply, Mary, and for all you do for us ME/CFS sufferers in North America.

I’d like to respond to you in the forums here: https://www.healthrising.org/forums/threads/me-cfs-professional-psychiatrist-clinical-advocates-perpetuating-inability-to-pace-myth.5227/

Here are my communications with IHME regarding the lack of FM and ME/CFS data

From Me

Thank you for replying Anna. I guess my next question is why you don’t provide specific estimates for one disease that affects about 10 million people in the U.S. (fibromyalgia) and probably hundreds of millions across the world or for chronic fatigue syndrome which effects 1-4 million people in the US and which studies suggests costs the U.S. economy up to 20 billion dollars a year.

I would note also that a Harvard study found that people with chronic fatigue syndrome were significantly more functionally impaired than people with congestive heart failure, type II diabetes, heart attacks and multiple sclerosis. (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8873490) yet it doesn;t warrant a single line in the IHME. How is that possible?

Both direct and indirect economic costs are available for chronic fatigue syndrome and I believe fibromyalgia. Health care utilization figure are present for fibromyalgia – https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25181721 . I can give you much more data.

How can the IHME fulfill its mission to provide information on diseases and conditions afflicting humans when it ignores these two diseases

Are there any plans to include either disease in the IHME?

Are there plans to highlight diseases that afflict significant numbers of people for which the IHME needs more data (if that’s the problem).

How does the IHME decide which diseases to include or not include in its data bases?

IHME Reply

I was able to discuss your questions and concerns with a researcher, and as mentioned we currently do not produce specific estimates for fibromyalgia or chronic fatigue syndrome, however they are included in our estimation within the “other MSK” cause. As “other MSK” is a rather large category, they do hope to split up the larger causes and create separate estimates for fibromyalgia, and chronic fatigue syndrome, among others in the future.

Thank you for your inquiry. If you have any other questions please feel free to email us at engage@healthdata.org.

Best regards,

Anna B.

From Me

Thanks Anna. What does MSK refer to you and how do you decide which diseases are put into that category? (I could not find it on GBD Compare)

When would you anticipate that the illness burdens for diseases like fibromyalgia and ME/CFS get broken out?

As you may guess diseases like FM and chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS) which have been historically under-funded rely on organizations like the IHME to provide accurate assessments of illness burden for all diseases. Allocating health dollars properly of course is the IHME’s mandate.

When it doesn’t include diseases that cost billions of dollars a year in economic losses or afflict millions of people in its assessments it’s obviously not meeting it’s mandate.

People with these diseases, of course, tend to see a pattern here – neglect even at the level of the IHME – something we would hardly expect. (FM gets $11 million a year from the NIH and ME/CFS is now listed as getting $7.

Thanks for your time

From IHME

Cort,

MSK is short for Musculoskeletal Disorders. In terms of the diseases that are put into these categories, I suggest that you take a look through the methods section of the GBD 2015 Years-Lived with Disability paper as well as the supplementary appendix which discusses other musculoskeletal disorders from page 447-480. Unfortunately, I have not heard anything more specific regarding a date to break out fibromyalgia and ME/CFS, however I’ll be happy to let you know you.

Thank you again for your interest in the Global Burden of Disease (GBD) study. Please direct further questions to engage@healthdata.org.

Best regards,

Anna

To Anna at the IHME

Just so you know there is no mention I can find in the methods section of that paper how IHME decided which diseases to include or not include in its research.

Nor is there any mention that I could find of fibromyalgia or chronic fatigue syndrome in pages 447-480 of the first appendix.

Given that fibromyalgia is believed to occur in 2-8% of the world’s women (http://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/article-abstract/1860480) I assert that the IHME is hardly fulfilling it’s stated mission to determine what the worlds major health problems are and how well society is addressing them.

IHME’s research is organized around answering three critical questions that are essential to understanding the current state of population health and the strategies necessary to improve it.

What are the world’s major health problems?

How well is society addressing these problems?

How do we best dedicate resources to maximize health improvement?

I just sent this out to the IHME

I could find no data on burden of illness of fibromyalgia or chronic fatigue syndrome in the U.S. in the IHME.

Chronic fatigue syndrome is believed to affect between 1-4 million people in the US (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17559660) and is more functionally disabling than congestive heart failure, diabetes, and multiple sclerosis (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8873490). Economic loses due to lost productivity alone are estimated at 9.1 billion dollars a year (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15210053) while total economic losses are estimated between 14-24 billions a year. Chronic fatigue syndrome is clearly a major disorder yet I can find no mention of it at all in the IHME.

Recent FM studies indicate that fibromyalgia affects between 2-5% of the population (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25323744), imposes a significant economic burden on both health care providers and patients )https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27084363) – similar to that found in rheumatoid arthritis (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19220165). FM is the mostly seen pain disorder in rheumatology clinics, yet is never mentioned, so far as I can tell, in the IHME databases or reports.

I was told by an IHME representative that both diseases were in the MSK category and to look through the supplementary appendix which discusses other musculoskeletal disorders from page 447-480. I could find no mention of them there.

The IHME’s stated mission is determine what the world’s major health problems are, how well they are being address and how best to address them yet it appears to have no data on two relatively common diseases which produce large illness burdens. The IHME includes many diseases with far lower prevalence reports and economic costs in its databases.

Because IHME is the trusted resource on illness burden it’s omission of underserved diseases such as these (fibromyalgia gets less than a $1 per patient per year from the NIH.) is doubly upsetting. IHME’s omission suggests these diseases are not serious and not worthy of public funding.

How does the IHME decide which diseases to include or not include in its data bases?

How does IHME plan to rectify its omission of these disease in its databases?

Are there plans to highlight diseases that afflict significant numbers of people for which the IHME needs more data (if that’s the problem).

How can the IHME carry out its mission when it’s ignoring diseases that affect millions of people in the U.S.?

Thanks for your time,

Yours truly

Cort Johnson

Hail, well met from Aussie. good health care system here, and free at the moment for most doctor approved meds and procedures. Tending towards blaming consumers/patients for being ill if the currently approved tests show nothing.

Metabolomics and proteomics are showing useful patterns in ME. My own experience with IM Mg injections which returned me to NORMAL for 12 months, after 10 years of ME, demonstrates clearly that for me anyway, this is a biochemical phenomenon.

The story of my year of wonder is briefly recorded somewhere else on healthrising. It has been 23 years since that ended and no amount, form, or type of application of Magnesium works for me now. However, having studied physiology, there are clues there in its working and in its stopping. I have too much brain fog and short term memory dysfunction to get very far with my online researches, though I try to keep an eye out for whats happening.

I call the condition Flat [or Faulty] Battery Disease [1003+ names and counting] and find it a useful phrase to describe it to others. Lighthearted I coined the name, but I find it more accurate than I first thought. The insipid SEID is to me, slightly more useful than saying PEM, describes our faulty battery status,and is not useful as a replacement for the name ME/CFS. We are always working with an impaired internal battery, and there seem to be many ways to fall into this situation, none of which we could have anticipated. A few find their way out early. For the rest of us, we are in a catch-22 situation on all fronts. There will be ways out, and I am watching, searching for clues as many of you are. Hang in there folks.

This health tracker gadget checks if a person is having

an enough train, consuming the proper kinds of meals,

and sleeping adequately.