- A Young Doctor Fights to Cure His Own Rare, Deadly Disease

- His Doctors Were Stumped. Then He Took Over.

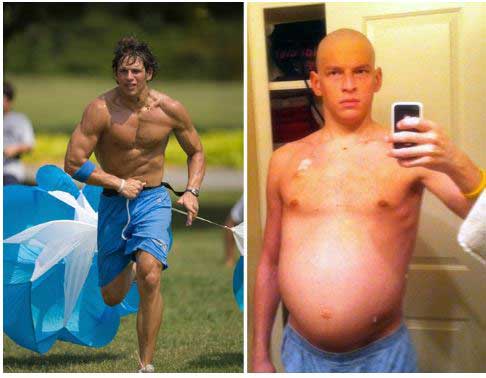

The “Beast” was just twenty-five years old. A physical specimen, David Fajgenbaum went from gym rat to invalid incredibly quickly. First his lymph nodes swelled, then red dots appeared on his chest. This medical resident got so fatigued that he began stealing naps in empty exam rooms. He became temporarily blind in one eye and then in two weeks gained 70 pounds. His ability to think plummeted. His doctors were stumped – cancer, lupus and mononucleosis were all suggested – and discarded.

He slowly improved after treatment with chemotherapy drugs and walked out of the hospital, but a month later his symptoms came rushing back. The Mayo Clinic diagnosed him with Castleman’s Disease – a rare disease that afflicts about 20,000 people in the U.S. – about the same number as Lou Gehrig’s disease.

Health and a New Disease Model

When he first became ill Fajgenbaum spent 4 1/2 months over a seven month period hospitalized. At one point he was administered last rites. Another bout with the illness left him near death again and he was given five years to live. Over the next couple of years he came close to dying five times. He realized that letting the research process proceed in its rather leisurely manner likely meant a death sentence.

Fajgenbaum got into action. He did two things: he began to make a meticulous record of his weekly immune test results to see if he could discern a pattern and he began to assess the entire field.

Like other CD patients, Fajgenbaum would end up flipping between relapses and remissions over the next couple of years – a pattern that ended up serving him well. Meticulously recording the results of his weekly blood tests, Fajgenbaum noticed his immune system began changing a full five months before his latest relapse.

First his T-cells turned on, then two months later an immune factor called VGEF started bumping up. Pay close attention to the next step because this is exactly what Ron Davis and other researchers hope to do.

Looking upstream Fajgenbaum found that activation of the mTOR immune pathway could explain both. The next step was simple: scour drug databases for drugs able to inhibit mTOR pathway activation.

A kidney transplant rejection drug called Sirolimus (Rapamune) that no one in a hundred years would have considered for Castleman’s disease, popped up. Fajgenbaum dropped his cancer drugs and started on Sirolimus and his immune system returned to normal.

It’s not clear how many Castleman’s patients the drug will work for, but three years later Fajgenbaum is completely healthy and is still disease free.

Relapsing-Remitting / Good Day – Bad Day ME/CFS Patients a Key?

Fajgenbaum had a disease that gave him — with its relapsing-remitting status — a shot at capturing the disease process as it proceeded. While little is heard about it – and no attention that I know of has been given to it in the research literature – ME/CFS does have its own subset of relapsing-remitting patients a similar approach might work on.

An online Health Rising survey suggested that many people with ME/CFS experience significant and repeated remissions from which they later relapse. A former doctor, epidemiologist and longtime ME/CFS patient, Dean Echenberg described what that’s like:

Over the past 30 years the illness has waxed and waned and not at all in a subtle away. It is almost like I have an on and off switch. The remission phases have varied in timing but not in character. At times I seem to be completely better. So much so that for years I thought I was “cured”. During this phase even close family, who didn’t see me when I was in the attack phase, had difficulty believing that there anything was wrong with me.

But then, when they saw me in the attack phase, (the bed to couch and back again phase) they had no doubt. All they had to do was look at me and they knew I was seriously ill.

I would seem perfectly normal; then BAM. It was obvious to them that, suddenly, there was something seriously wrong with me. This was especially problematic for me during the earlier decades when I became ill. If I saw a clinician during a remission phase, I was almost embarrassed to tell them what was wrong, it seemed so far-fetched.

Extensive testing of these patients could possibly reveal pathways that are becoming activated or de-activated in ME/CFS as they become ill. These patients could have a different disease entirely or they could have a turn-off switch that allows them to temporarily escape ME/CFS. If the later is the case both a turn-on and turn-off switch could be identified. The task is a bit harder with ME/CFS because we don’t know that it is an immune disease or which factors to test. Nor has anyone that I know highlighted the relapse-remission (R-R) subset.

In lieu of identifying an R-R subset, several good-day /bad-day studies that are underway may also identify which pathways get activated (or de-activated) as patients get worse or better. Ultimately, attempts could be made to use drugs that turn those pathways on or off.

New Disease Model

Fajgenbaum began to understand the critical need to think outside the box. I recently had a conversation with Ron Davis in which he asserted that it was essential for us to think about chronic fatigue syndrome in new ways.

Fajgenbaum began to wonder if the accepted wisdom around Castleman’s disease was wrong. The lymph nodes doctors believed were driving the disease looked exactly the same as the lymph nodes in people with rheumatoid arthritis and other diseases. Plus IL-6 didn’t always correlate with disease relapse and chemotherapy used to treat the tumor believed to be producing the lymph node issues across the body didn’t always produce results.

Something else had to be happening. Ultimately Castleman’s disease went from a disease believed to be caused by tumors that produce cytokines to a disease caused by a hyperactive immune system that produces cytokines. It went from a disease primarily treated by chemotherapy to a disease treated immunologically.

Flipping Biomedical Research on its Head

“Depend upon it, sir, when a man knows he is to be hanged in a fortnight, it concentrates his mind wonderfully.” Samuel Johnson

Becoming a patient had changed Fajgenbaum’s approach to research. Fajgenbaum had never considered the biomedical research process problematic until he came to be a patient, but the inefficiencies present quickly became apparent.

Faced with a dismal diagnosis and a five year life expectancy, Fajgenbaum dove into action. After Josh Summer, a young man with another rare disease, urged him to produce a game plan “to drive the sometimes rickety research train toward a clear destination”, Fajgenbaum contacted Castleman’s researchers and set up a meeting.

The meeting revealed an isolated research community stuck in procedural and methodological issues much like chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS) has been. Few researchers collaborated with each other, and many – coming from different fields – didn’t even know of each others’ work. Disagreements about basic issues such as disease terminology and which cells were worth studying left research efforts floundering. No consensus criteria for diagnosis had been produced, medical information on the disease was often wrong (the UpToDate website was not ‘UpToDate’), and the accepted model for the disease didn’t make sense. Plus there was zero patient advocacy.

Realizing that the disease was in desperate need of a game plan, Fajgenbaum changed course. Upon completion of his medical degree he headed back to college to get an MBA at the prestigious Wharton School of Business and produced a road map for a disease cure. Drawing on what he learned, Fajgenbaum formed the Castleman Disease Collaborative Network (CDCN) that was designed to facilitate collaboration, mobilize resources and invest in impactful research.

It wasn’t just Castleman’s disease that was the problem. Fajgenbaum had become schooled in problem solving at Wharton. Looking at the way we approach disease from a problem-solving perspective, Fajgenbaum came to believe that the way the medical profession, in general, attacks diseases is slow, inefficient and wasteful.

The current research paradigm is usually driven by a grant application process where individual researchers are rewarded for creative grant applications. Fajgenbaum realized that a process which rewards individual initiative can easily ignore the needs of a field. Fundamental problems (such as diagnostic criteria) can hamper a field for decades if no one in the field steps forward to address them. (Witness the Fukuda Definition in ME/CFS). A field can grow rapidly or not depending on which researchers it happens to attract.

If no one is watching out for the needs of the field, they very likely will not be met. Overarching strategies dedicated to highlighting basic research priorities and knocking them off one by one will likely not be developed. Plus the competitive nature of the grant application process prevents collaboration and patients are often excluded from the research process completely.

Fajgenbaum used his Wharton Business school experience to strategize. The Castleman Disease Collaborative Network (CDCN) Fajgenbaum created set out to advance disease research in three phases.

First they connected 400+ physicians and researchers via meetings and discussion boards and 6,000 patients and supporters through online portals. Researchers were asked for a list of possible studies and Fajgenbaum’s team developed a list of high priority research projects, one of which included sifting through lymph node samples for pathogens that might be triggering the disease.

The next step in that project included making a list of the top immunologists in the world to test the samples (if this sounds like Ron Davis’s vision of how an ME/CFS consortium would work, it is…). Then a bit of serendipity struck. One of Fajgenbaum’s partners had a connection to Ian Lipkin and Lipkin – their top choice – agreed to help out.

The CDCN also created a state of the knowledge resource, established an ICD-10 code and convened an international symposium to establish diagnostic criteria, and is building an international patient registry. It was able to increase research funding ten-fold between 2015 and 2016.

In the meantime the first drug for Castleman’s Disease was FDA approved.

Rare Diseases Make Good

Prevalence statistics indicate that chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS) and fibromyalgia (FM) are not rare diseases but in other ways they are similar. Low funding levels plague ME/CFS, FM and many rare diseases.

(The NIH does not list funding levels for Castleman’s Disease. The fact that it does not list funding levels for Sjogren’s Syndrome, irritable bowel syndrome or Chorodoma either demonstrates another strange inconsistency. Because the NIH uses data mining searches to come up with its funding totals, there’s no reason it can’t come up with numbers for those diseases – it just doesn’t.)

Even rare diseases can be successfully attacked. Josh Summer’s Chorodoma Foundation, for instance, brought in $2,000,000 for a rare type of bone cancer that affects 1 in 125,000 people. Only 2,400 people in the U.S. have it yet the foundation is currently screening six drugs. ME/CFS and FM patients may howl at the discrepancy, but in some wasys Chorodoma is easy compared to ME/CFS and FM; the diagnosis and proximal cause of the disease is clear – a tumor.

The same is true for Castleman’s disease. Fajgenbaum’s sudden collapse when he was twenty-five was accompanied by widespread organ problems. It was clear from the beginning that Castleman’s was an immune mediated disease. Contrast that with ME/CS where no real consensus around cause has emerged. A strategic approach, nevertheless, is beginning to show up.

Ron Davis’s vision of an international consortium taking on ME/CFS along the lines of the Human Genome project has yet to been achieved, but there is some movement to bring order and a common vision to this wide and varied field. Suzanne Vernon has been promoting ways to mature this field for as long as I can remember. Zaher Nahle, the Research Director of the SMCI, took a similar path to Fajgenbaum. After immersing himself in the medical field he went to the Kennedy School of Government in order to learn how to make the biggest difference. The talent and the vision is there – the resources are not yet but they are emerging.

- “Get Your Motor Running” – Zaher Nahle Takes on Chronic Fatigue Syndrome

The Pathways to Prevention Workshop for ME/CFS identified research priorities and gaps in current research that informed the NIH’s RFA’s. Those RFA’s require that the new research centers collaborate with each other and provide a common data center.

The Open Medicine Foundation has pledged to make its data public. A Common Data Element (CDE) project that requires NIH research studies to use common data elements will allow studies to be directly compared for the first time and that should help produce a new research definition. The Solve ME/CFS Initiative is expanding its Patient Registry.

Some of the infrastructure, then, is being built yet both ME/CFS and FM have so far to go. As welcome as any increase in funding is, the NIH’s RFA’s for ME/CFS are simply a down payment on the funds really needed to build a strong and vibrant field.

An organized, efficient, well-resourced approach to ME/CFS can be created. Autism’s rise to significant funding was bolstered by a $25 million dollar contribution, the unification of three organizations and the development of a united front. Something like that could happen in ME/CFS or FM.

Over a million people in the U.S. likely have ME/CFS, most of whom don’t know they have it. Millions more have fibromyalgia. Every effort to raise consciousness, every media event like Unrest, every blog or media post shared, every book like Valerie Free’s “Lighting Up a Hidden World” promoted, every sharing of our stories in any number of ways expands understanding, recruits new allies and potentially touches the people who will make the big difference in this disease.

A recent conversation changed one group’s approach to a treatment for muscle wasting disease. Realizing that their proposed treatment probably works better for ME/CFS they switched diseases and are now focusing their efforts on ME/CFS. It’s not clear that their approach will work but the trigger was sharing: they learned about ME/CFS from a conversation with Dr. Montoya. (A blog is coming.)

Most people are too sick to do much. We can’t build a truly successful effort on the bodies of people with this disease but we can reach out, we can find the allies who have the strength, the commitment, the guts, and the resources to make the difference this disease is calling out for.

More healthy people like Mary Dimmock, Linda Tannenbaum and Carol Head are out there. The big donor able to pledge the $10 million a year or more to lift this field onto its feet is out there. The person able to declare that they’ll pledge $2 million a year, if five or ten other people join them – that person is out there. The horrific effects of this illness calls for things like that to happen. Our job is to share, share, share – so that it does.

Keep the hope alive.

This is the most important article I have read about this field in a long time. We definitely need to get beyond the inefficient process of inching along in uncoordinated efforts which have sometimes dead ended or gotten stuck in circular loops. I am thinking of an image of an uncoordinated ant colony or beehive, when how we need to be now is like those normally coordinated beehives or ant colonies–the models that the social insects, above all, can provide.

Exactly. It’s not only that we have not prioritized our needs and followed that strategy (Dr. Kogelnik actually did that when he started the OMF) but we’ve left a look of good studies behind that were not followed up on and validated.

This is a very complex disease and undertaking. We don’t just need a master plan – we need the resources to carrying it out. I think the development of a master plan – and one may be sitting out there- could help bring in the resources.

The fragmentation of the research into this illness has frustrated me for a long time. It is hard to keep hope alive when the train is moving so slowly and the times of “remission” are farther apart and more like, walking for five minutes a day instead of being able to have any kind of real life at all. I commend you, Cort, for your tireless (pun intended) work to inform us, your community in ME/CFS. I know how hard it is to function even minimally in the real world these days. I have kept hope alive for over three decades, and just wish I knew back in the 80’s what I know now about using those remissions to their best advantage instead of thinking I was miraculously cured forever and surging full steam ahead again. You and your work is so much appreciated, I know, by more than just me. I keep reading and keep hoping.

The lack of coordinated research has indeed been enormously challenging and hope-draining over the decades. That noted, I do want to second Joya’s praise of Cort. His dependably constant, intelligent, timely and thoughtful insights have kept hope possible over many of those years. Here’s to a more efficient research plan going forward, and heartfelt recognition of Cort’s meaningful contribution to the conversation and to our wellbeing.

Thanks! 🙂 🙂 🙂

Another brilliant article, Cort – keep up the good work; I don’t know anyone else who brings together so well the disparate strands of different areas of research. I asked the question [in writing] about why no-one was studying the difference between remission/relapse and the difference between good days/bad days at least 20 years ago here in the UK, but garnered no interest whatsoever. When I am in relapse, the difference between good days and bad days is so marked, I feel like Jekyll and Hyde; my logic was that this huge difference had to show up in my metabolism somewhere, if only someone could be persuaded to look.

Thanks. Probably since I’ve never experienced them I was really surprised at how many people experience remissions and relapses. It’s quite a significant number. Why that group has not been highlighted more I don’t know. In a better funded disease I think they would have been looked at by now.

It would be fascinating to compare the immune and other systems of people in remission or who are recovered and those were are ill – possibly severely ill. Similarities in people who were recovered or in remission and those who are ill might indicate underlying defects that predispose people to ME/CFS. (Ron Davis is looking into this). Differences could indicate the wrong turn the immune system has taken.

Hi, I am one of the remitting/relapsing, when I relapse it lasts for years.

my first one was 3 years and then left and I was pretty much 100%, then had a few little relapses (days to 4 months) then again gone but new there was something lurking. It returned in 2013 after pneumonia and I am still in the relapse.

Iam lucky, I can still work, now part time and am due to return to the m.e/cfs unit soon after a potential breakthrough for me, I got a dental abscess and got placed on metronidazole, I was brilliant for 5 days upto the high 90% and did things not done since 2013, then over the next 24 or so hours it slowly came back so I am hoping for potential controlled trial on the metro.

I echo whats already been said, there is loads of us remitters, we need the medical community to utilise our results to help everyone with this.

I actually have to call one on myself. I actually did have a relapsing-remitting case of ME/CFS. I first became ill while at University – returned home – got better – did a lot of exercise – only to really fall apart later.

From then on its pretty consistent but for a time there I did remit.

From my own experience, I believe our immune systems are overactive in a similar way to Fagjenbaum’s. I am hopeful that our researchers are already sharing information. Cort- I guess that Ron Davis is aware of the latest findings of Fluge and Mella? I do hope it won’t be too many years before there are treatments availale!

Davis is VERY aware of Fluge and Mella’s findings. A blog on Ron’s and the OMF’s latest work will be up soon.

I agree about the similarities between Fagjenbaum and ME/CFS. Fagjenbaum believes that the disease may be triggered by a pathogen; that suggests that the difference between CD and ME/CFS and FM may simply lie in the immune pathways the pathogen triggered.

I have always thought that my immune system is hyperactive, hence the severe food and chemical reactions. I rarely get colds or flu but a persistent low grade temperature and chicken pox like vesicles around my hairline occur each time. I had the original Salk polio vaccine in 1957 as I was a RN in an acute polio unit. So many possible triggers. Where to start? 35 years later, still no-one knows.

Great article Cort…I first got very ill for approx 2 months in late 2015 but then over period of 1 month I remitted completely and I was 100% confident that I was better…The weekend before I relapsed I had gone for a long run, swam, played tennis twice… And then collapsed and haven’t recovered…now I am in a wheelchair to leave my apartment…Interestingly, my Dr (Dr John Whiting) keeps track of my Ferritin levels as an indicator of inflammation and I can now predict my latest test results based on how I am feeling before he tells me the results…Also, I am someone who seems not to get ‘normal’ sicknesses now- last winter when everyone around me was sick with the flu, I was virtually bedbound with me/cfs but never looked like getting a cough or a sniffle…

What a story Anthony! I hope you get better. Can you say more about your ferritin results? Are they high or low when you start moving into a relapse?

yes ferritin is always relatively high since getting sick…So when I have been bed bound or close to it ferritin tends to be in 400’s up to about 480 and when I am at me best which is able to move around apartment quite comfortably and feeling almost normal when sitting or lying ferritin tends to be 250-300…

Hi Anthony,

Do you happen to have red blood cell counts with your blood test results? As red blood cells contain a really high percentage of our bodies iron and ferritine is used to store iron that gets set free I do wonder if it has to do with an immune reaction where red blood cells die at a very rapid pace. Usually it is continuous, but as we have quick PEM onsets it may be more in bursts.

-> do you see a correlation between red blood cell counts and ferritine? I would suspect an inverse relation: lower red blood cell counts with higher ferritine if this process would somehow happen. Changes in blood volume can however complicate things. Hematocrit levels may be another factor where there is correlation; they vary according to the need of forming new red blood cells.

It is a long shot, but who knows?

Today, I completed a methodical search for an immunologist here in Seattle to take a look at my suppressed immune system, viral and bacterial titers, high serum ferritin, etc.

All of this was triggered by chemotherapy. I beat stage 3 cancer to have ME/CFS.

Turns out that the only MDs in town who’d be able to understand my labs and help me only work on people with active cancer.

Without active cancer, I’be been repeatedly told to go to a family doctor, psychiatrist, or a pain clinic…

The representative from the famed Seattle Care Alliance broke the news today that she and a researcher had looked for a way for me to get seen and came up with nothing.

She said she saw what a difficult spot I’m in that there are no answers for, and apologized. Last week, my oncologist apologized for doing this to me, too.

In the meantime, there are daily articles on the millions being spent on Opdivo, Keytruda, etc. to try to rev up the immune system to fight cancer, with decidedly mixed results… they may prolong lives by mere months…

I’m struck by the fact that our most brilliant immunologists aren’t looking at ME/CFS… they’re working on prolonging cancer patients lives by a few months.

Check out functional medicine northwest, a Dr. Iller and Dr. Chandra at Swedish.

I am one of the few people who know definitively what caused my CFS. It came on me like a ton of bricks exactly 3 Hours after my second radiation therapy treatment for Stage 0 breast cancer. That was 7 years ago. My doctor believes that this “flipped a switch” in my immune system, M asking it hyperactive.

I am treated with several drugs that “suppress” the immune system. I have gone from bedridden to functioning at 50% of my pre-CFS self. Not cured, but definitely improved.

I would love to try Rituxan and I pray that someone does a Rituxan clinical trial in the US.

I have been relapse remitting for over 35 years. I recently stopped antiviral treatment and am taking Rapamune (mTOR inhibitor) under guidance of an oncologist/hematologist who has had success with a handful of ME/CFS patients encountered by chance I his practice, with one specifically seeking him out backed by informative research papers. My primary symptoms include severe PEM, sensory and cognitive issues after over exertion, no colds, flu or sore throats for over 2 years during this relapse. Highly irregular since remission phases I have constant infections. I have high EBV and CMV IGG TITERS but negative on PCR tests. No confirmed immune abnormalities because Doctors have not performed deep dive tests, but I personally am convinced something defective there. I will post progress on Rapamune. Cory your description of interdisciplinary collaborative investigation – outside the box is spot on.

Thanks! Good luck with the Rapamune and please tell us how it turns out.

Please tell me, who is your doctor of oncology/hematology?

Phyllis please email me as I hesitate to publish his name here without his permission. I am in the Dallas area.

Hi Marcia, I’m also very interested in speaking with this physician. But I don’t see any way to email you to find out the name of the doctor. How can I get in touch with you and/or the doctor?

Thank you in advance for any guidance.

Cort – I just came down with horrible case of flu the day after my husband became ill and just 2 weeks after starting Rapamune. Understand that I have not been ‘normal’ sick for 2 years since this last relapse with plenty of sick grandkids around too. I am sure it is all much more complicated – but apparently the mTOR Inhibition has some effect. Of course I feel horrible as one does with the flu but so very excited about the implications. After starting Rapamune and prior to getting flu I was increasing in small increments in functionality daily. I have stopped the Rapamune while getting through this flu but need counsel from the doctor on go forward. I will post this in a treatment thread if continued progress.

Marcia, can you update us on your treatment results?