Veronique’s article is one of a series of articles from Health Rising featuring hypotheses created mostly by health care professionals with or who are associated with ME/CFS. They include:

- What if ME/CFS is an Intelligent Process Gone Awry?

- Could Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS) Be a Chronic Form of Sepsis? (Dr. Bell – ME/CFS physician)

- The RCCX Hypothesis: Could It Help Explain Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS), Fibromyalgia and other Diseases?

Veronique had a very gradual onset of ME/CFS beginning in the 1990s when she was a family physician. Her symptoms worsened slowly over 10 years. At her worst activities such as sitting, standing, taking a shower, or talking exhausted her.

Veronique, a former physician, has had ME/CFS for about 20 years.

She changed careers and has since discovered and integrated research on how adverse life events (ALEs) affect health. The science dispels the out-of-date notions that such effects are psychological and that their influences on risk mean that chronic illnesses are psychosomatic.

Veronique has been researching the role of the nervous system and how it learns to perceive threat as an important and under-recognized contributor to chronic illnesses of all kinds. Not because chronic illness is psychosomatic or that being sick is our fault – but because life events shape our genes and biochemistry as well as how our nervous systems and physiology’s function.

Her work is informed by her background as an assistant professor of medicine; published research; an MA in somatic psychology with specialties in traumatic stress and body based psychotherapies; work with clients with chronic illness; as well as her own experiences with debilitating chronic illness. Check out Veronique’s website here.

Introduction

Over the past 15 years I have come to a different way of thinking about chronic illness as a result of findings I never heard of in my training as a physician. These come from a large body of scientific studies in medicine, epigenetics, brain plasticity, embryology and early development, neurophysiology, epidemiology as well as research in different types of chronic illnesses. We’re learning now that life experiences affect health. This is not because our diseases are psychosomatic as has long been believed and used to judge many who are sick. It’s because the new science of epigenetics is showing us that life events interact with our genes to affect our physiology and long-term health. This includes physical health and chronic illness as well as mental health.

In this post I start with what I discovered about type 1 diabetes, which has helped me make sense of my own long-standing experience of ME/CFS, asthma and other symptoms. I’ve had debilitating fatigue for 20 years that gradually worsened over a decade. At its most intense in 2009 my fatigue felt “death-like” and I had difficulty sitting, standing and talking for almost a year.

The perspectives I learned about have helped me make strides since then, and I have been slowly improving to the point where I can run errands and walk 40 to 60 minutes most days among other things. These views have also given me a context from which to understand the evolution, course and gradual resolution of my disease.

I’m still limited by my health and I offer no quick fixes. The research, however, provides a different way to work with and begin to make sense of the symptoms present in ME/CFS and other chronic illnesses, recognize triggers, understand why treatments can work at first and but then decline over time or even stimulate resistance and more. It also offers some new tools to add to the few that do work (for some – some of the time) in ME/CFS.

This first post is part of a series introducing the science that lead me to this new perspective. I have written a second post describing an unexpected treatment that heals asthma by addressing risk factors from pregnancy, birth and infancy described below. My third post presents the emerging understanding of mechanisms that explain these findings, starting with how early experiences alter genes. I’ve included a few references here and a little more detail in my original article. There are more posts to come.

My current view of chronic illness, including ME/CFS, is that it:

- evolves through adaptations in our brains and nervous systems – and how they learn to perceive threat,

- involves a process that begins long before onset or diagnosis,

- results from a similar process in diseases as different as type 1 diabetes and heart disease at one end of the spectrum, and asthma, Parkinson’s, and ME/CFS at another.

- occurs after exposure to multiple events or “hits”

- follows a different pathway for each person – even in the same disease

- may be caused by different mechanisms – even in the same disease

First Steps. A Look at Type 1 Diabetes (T1D)

I began my explorations with type 1 diabetes (T1D). Unlike ME/CFS, fibromyalgia and some other diseases, T1D has clear diagnostic criteria which consist of high glucose levels in the presence of low to zero levels of insulin. These criteria make TID easy to identify and study.

T1D is the less common form of diabetes and is most commonly caused by an autoimmune process. In T1D survival depends on treatment with insulin. This contrasts with the more well-known type 2 diabetes (T2D), which can be associated with obesity (though not always), and can sometimes be managed through diet, activity levels, and weight loss or through oral medications or sometimes insulin shots. The lines between these two diseases are becoming increasing blurred and an epidemic of both is on the rise.

I also initially focused on studies in T1D because of the judgmental tone and blame so frequently encountered in the ME/CFS community and promulgated by some types of ME/CFS. No one would ever tell a person with T1D that their disease is all in their heads or psychosomatic, or that all they have to do to recover is to meditate, decrease their stress levels, exercise, do cognitive behavioral therapy, develop better health habits or to just “try harder.”

What I found in the T1D research, though, turned out to apply to other diseases – including my own. I’ll come back later in this series to describe these similarities.

What if chronic illness reflects an intelligent mechanism gone awry?

When I first started out to better understand chronic illness, I wondered whether the underlying drivers of disease might reflect an intelligent, natural process rather than one in which something is broken or in which our bodies are mistakenly attacking themselves.

I wondered whether the state of glucose dysregulation seen in T1D could also be found in normal, healthy functioning.

I thought about how levels of glucose and insulin vary according to the physiological states of our bodies. In states of parasympathetic nervous system (PNS) dominance where “rest and digest” processes prevail, for example, increased insulin availability enables glucose to enter cells. It also maintains blood sugar at remarkably constant levels.

In contrast, a sympathetic nervous system (SNS) response that occurs during jogging or a fight and flight type situation – results in a decrease in insulin and a concomitant rise in the availability of blood sugar. Together with other hormones, SNS states manipulate insulin and glucose levels to make sugar available as a source of fuel to be utilized by muscles when running, fleeing or fighting.

I realized that this SNS state is also a snapshot of T1D.

I wondered if something could lead to prolonged states of autonomic nervous system (ANS) arousal and high glucose levels in the face of low insulin. ????

And I wondered whether such states, like shifts into and out of fight and flight, were reversible.

Risk for most chronic illnesses is only partly genetic

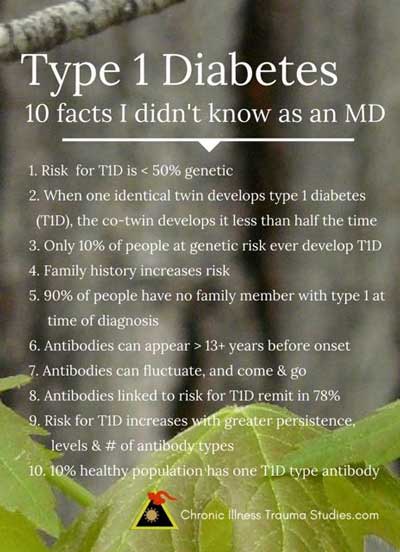

In learning more about T1D, I made a series of unexpected discoveries my medical training had not prepared me for:

- Only about 50% of the risk for T1D is genetic. If an identical twin develops T1D, for example, the co-twin develops T1D less than half of the time (Diabetes Epidemiology Research International, 1987; Nistico, 2012; wikipedia). (The risk for many other chronic illnesses is also less than 50% genetic.)

- Only 10% of people at genetic risk for T1D ever develop the disease (Knip, 2005; Dahlquist, 1989).

- Although people at high genetic risk are more likely to have a family member with T1D, 90% have no close relatives with T1D at the time they are diagnosed.

These findings suggested that even when there was a genetic predisposition, development of T1D and other chronic illnesses was not a foregone conclusion. It showed that even people at risk had a remarkably low chance of developing the disease. And if T1D was genetic but didn’t come from family members with a similar disease, it suggested a very different set of risk factors.

Studies indicated that fifty percent of major risk factors T1D – and for many other chronic illnesses – are not genetic, but environmental factors that derive from what we experience and do. This includes exposures, such as to vaccines, toxins, or infections or to low levels of vitamin D; smoking; diet and nutrition; place of birth; parental socioeconomic status; birth order or number of siblings and the like.

Unlike our genes, environmental factors are sometimes within our power to choose or change (diet, smoking, supplements, exercise, etc).

Because relatives disabled by ME/CFS are present on both sides of my family tree, I wondered whether genetic predisposition existed for me but, like T1D had simply failed to manifest in everyone.

Antibody patterns show that risk for T1D is not set in stone

Many people with T1D have one or more types of antibodies at the time of diagnosis. Another discovery I made was that these antibodies have many intriguing characteristics:

- The presence of one antibody associated with risk for T1D is common in the general population (Knip, 2005)

- Only a small number of people with insulin-related antibodies ever develop T1D

- The existence of antibodies remits in up to 78% of people (ie: antibodies are not always permanent) (Bennet, 1997)

- The higher the levels and types of antibodies and the longer they persist, the greater the risk of developing T1D

I hadn’t known that a lot of us carry risk factors for T1D but never develop the disease. Nor did I realize that the existence of antibodies is not always permanent, and therefore does not imply a clear or direct path to disease. My own antinuclear antibody (ANA) levels, a fairly general antibody not specific for ME/CFS, were abnormal in 2009, rose slightly over a few years, and then went back to normal around 2015.

As I researched further, I realized that the existence of antibodies, and the patterns being discovered in T1D, offered me a way of potentially understanding and tracking the effects of environmental factors that make some people more susceptible to coming down with a chronic illness.

Risk for Chronic Illness Begins Long Before Onset

- Antibodies in people who develop T1D arise over a period of time (Yu, 1996)

- These antibodies can appear up to 13 years (and possibly longer) before onset (Johnston, 1989)

- Antibodies associated with lupus (systemic lupus erythematosus or SLE), another autoimmune disease, have been found to occur up to 9 years before the onset of clinical symptoms (Arbuckle, 2001). As in T1D a greater number and persistence of these antibodies predicts greater risk although not everyone with these antibodies develops lupus (Arbuckle, 2003) .

Pic 2: Type 1 Diabetes 10 facts I didn’t know as an MD

Researchers in T1D proposed that environmental factors initiate or accelerate an underlying autoimmune process that triggers TID. They suspect that the environmental factors which precipitate or trigger the onset of T1D may be unmasking a process that has been developing out of sight and outside of our awareness (Dahlquist, 1998).

This information prompted me to recall two brief periods of inexplicable fatigue I’d experienced long before the onset of my ME/CFS. Both had been in response to exercise. One period had occurred in childhood and the other in college more than 10 years before the onset of my ME/CFS symptoms, which started in my 30s.

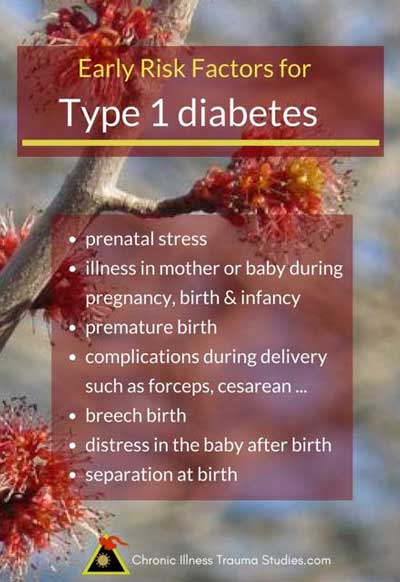

Events Occurring Before and Around Birth Can Increase the Risk of Coming Down with T1D

Because T1D commonly begins in childhood and antibodies can arise a long time before clinical symptoms ever begin, researchers began looking for risk factors occurring very early in life, including during pregnancy and birth.

Dahlquist and her group (1992) found that, in addition to the presence of diabetes and/or the increased age of the mother, the early childhood factors that increased one’s risk of coming down with T1D later included:

- being born prematurely

- a maternal illness such as pre-eclampsia (toxemia)

- delivery by caesarean section

- a neonatal respiratory illnesses

- and blood-group incompatibility

Dahlquist et al wondered whether the common element for many of the prenatal risk factors they’d uncovered was simply that they each represented some form of prenatal stress.

The fact that prenatal and birth events could affect risk for a chronic illness was news to me.

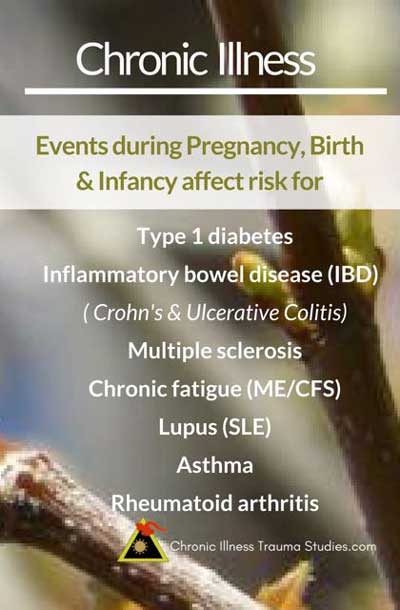

Prenatal and Birth Events Also Increase the Risk for Other Chronic Illnesses

The fetal origins of adult disease (FOAD) hypothesis comes from a large series of prospective and now multigenerational studies showing links between prenatal events and adult health.

The original study followed babies whose mothers experienced starvation during a siege in World War II known as the Dutch Hunger Winter. These studies indicated that nutritional stress is strongly linked to an increased risk for metabolic syndrome (heart disease, high blood pressure, elevated cholesterol, type 2 diabetes and/or obesity) and other chronic illnesses. The study findings have been widely replicated. They show that prenatal stressors such as nutritional deficiencies and emotional distress can increase the risk for metabolic syndrome and other chronic illnesses.

Additional research links a wide variety of prenatal events to risk for other chronic illnesses. Such risk factors include:

- infections and illnesses in mothers or babies during pregnancy

- infections and illnesses in mothers or babies in the first days after birth

- premature birth

- complications during delivery (forceps, caesarean delivery, use of certain medications)

- breech birth

- distress in the baby after birth (such as evidenced by the need for neonatal resuscitation or low apgar scores)

Prenatal and birth events have been associated with risk for chronic illnesses such as:

- inflammatory bowel disease (Crohn’s, Ulcerative Colitis) (Ekbom, 1990 & 1991)

- multiple sclerosis (Maser, 1969; Maghzi, 2012)

- asthma (Lewis, 1995; Oliveti, 1996; Xu, 2000; Madrid, 2005-2012)

- type 1 diabetes (McKinney, 1997; Patterson, 1994; Sepa, 2005; Stene, 2004)

It has also been suggested that events occurring during the prenatal time frame are associated with risk for lupus (Edwards, 2006) as well as ME/CFS (Dietert, 2008), among others.

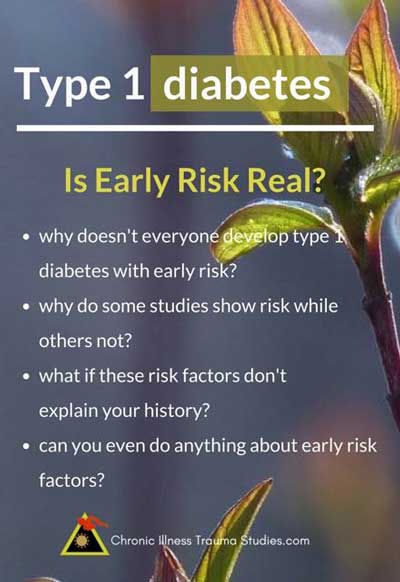

Unanswered questions

- Not everyone exposed to difficult prenatal events develops a chronic illness.

- Specific risk factors increased the chances of chronic illness in many studies, but not in all of them. The risk for T1D was higher with caesarean births in some studies, for example, but not in others. The same was true for most risk factors.

- None of these issues seemed to fit my own history. My mother had had a normal pregnancy. She had not experienced starvation, illness or problems in delivering me, for example.

Another big question for me was, “Why care about such risk factors if you can’t change them?”

Delving further into Dahlquist’s study, I became curious about her second finding, which was that blood-group incompatibility was the greatest risk factor for T1D.

The Greatest Risk Factor for T1D

Blood-group incompatibility occurs when a mother and her fetus have different blood types. It can cause symptoms ranging from mild to life-threatening. It’s also one of the most common causes of jaundice in newborns. Dahlquist couldn’t tell what the risk was specifically associated with. The standard treatment for jaundice at the time (as well as today) involved the newborns being placed in incubators where they were given phototherapy.

Dahlquist replicated this protocol in a study with T1D-prone mice by exposing one set of mice to isolation. She removed one set of pups from their cages for two 4-hour periods a day for 5 days during their first few days of life (1997). Another group which stayed with their dams was either treated with light therapy or a treatment.

A whopping 30% of the little guys who were separated from their mothers died compared to very few in the control group. A significant percentage of the treated group who survived developed T1D.

Dalhquist discovered that the risk factor for T1D was not the treatment, the jaundice, nor the blood group incompatibility – it was the separation of mice pups from their mothers.

I’d never heard of this as a risk factor for chronic illness either.

III. Maternal-Infant Separation Affects Health

Some of the first research I discovered regarding the role of maternal-infant separation was conducted by Columbia University professor and physician Myron Hofer (1994). He came to work one morning in 1968 to find that a mother rat had escaped her cage and that her pups’ heart rates were 40% below normal.

Over the years he discovered that close physical proximity between adult animals and their offspring regulates multiple autonomic nervous system processes that babies are not fully able to control on their own. This is due to the immaturity of their nervous and immune and other organ systems at birth.

The process by which close proximity enables offspring to regulate their physiologies involves what Hofer calls “hidden regulators.” He’s discovered that such subtle regulators include smells, pheromones, physical activities such as suckling, and other unconscious, ANS-driven processes and behaviors.

As Dahlquist found while looking at risk factors for T1D, human physiologies are affected by separation and proximity too. She noted that separation was a common result of many of the prenatal stressors that had been identified in her study – including infection and illness in the mother or baby, premature births, the need for treatment and more etc.

Prenatal stress is a well established but as yet still poorly recognized example of an environmental (nongenetic) risk factor for chronic illness.

Separation affects physiology in newborns

Human babies’ nervous systems and brains, immune systems, guts and other organ systems are immature and still developing at the time of birth. Progress in our understanding of early development has shown that basic functions such as body temperature, heart rate, blood pressure, cortisol levels, the functioning of the HPA axis, and levels of activation or arousal, among others, respond to proximity and separation in mammals. The same is seen in humans (Klaus, 1976; Schore, 1994; Sandman, 2015).

This body of research has lead to the use of practices such as Kangaroo Care in neonatal intensive care units (NICUs), in which premature and other babies are held in skin to skin contact by their parents in their first days and weeks of life. These neonates make more rapid health gains than when they are cared for solely in incubators.

Dr. Martha Welch, a former mentee of Dr. Myron Hofer’s, cofounded The Family Nurture Intervention at Columbia University Medical Center. Her treatment approach is part of a research study which is demonstrating that support for connection and calming early contact between mothers and their premature babies in the NICU improves neurodevelopment, cognition, behavior and other risks associated with early separation (2015). Her program was presented on PBS in May, 2017.

Early Separation Affects Risk Across Multiple Generations

Another striking finding in Hofer’s research was that experiences of early separation in rats influenced their risk for and susceptibility to disease such as high blood pressure in the teen years and adulthood. As studies in the role of prenatal stressors have also found, these effects can persist for multiple generations.

The same patterns are seen in humans.

How Early Separation Can Cause Chronic Illness and Why it Offers Hope

The NOVA documentary “The Ghost in Your Genes,” (here’s a transcript) describes the effects of environmental factors, including prenatal events, on health.

The influence of nongenetic factors is increasingly understood to be affected by epigenetics. Epigenetics is also the process by which experiences of prenatal stress influence multiple generations.

Epigenetics is the process by which small chemicals attach to the surfaces of genes and alter their behavior by turning them on and off. Epigenetic changes are influenced by environmental factors and can be transmitted from one generation to another. Exercise and diet, medications, as well as some types of psychotherapy that work with the nervous system to reduce perceptions of threat and effects of trauma can sometimes reverse epigenetic changes as well (Yehuda, 2013).

The new knowledge that we are gaining allows for the development of different ways of understanding chronic illness. The current paradigm which asserts that psychological events – such as life experiences – cause psychological illnesses while physical events – such as infections, genetic mutations etc. – cause physical conditions, is incorrect (Baldwin, 2013). The emerging science also suggests new possibilities for treatment as well as approaches for prevention.

Conclusion to Part I

One of the things I learned about chronic illness is that non-genetic risk factors such as early life events can affect biochemical pathways that influence our long-term health.

This is because our brains, nervous systems and other organ systems are genetically programmed to develop through interactions with our environments, including our mothers during pregnancy, birth and infancy (National Research Council and Institute of Medicine, 2000; Sandman, 2015; Schore, 1994; Shonkoff, 2012 & 2016).

Most children and adults today have experienced periods of early separation in the hours and days following birth. This was, and often still is, a routine part of healthy newborn care in hospital-based birthing settings. Babies who are sick, are delivered by caesarean, require treatment or whose mothers are ill experience longer periods of separation. Such practices are one risk factor among many that either predispose us to risk for chronic illness (among other health problems) or which accumulate over time with other non-genetic factors to gradually increase risk. I share more about this finding in the next post of the series.

Ultimately, the effects of early separation have been greatly underestimated. They are, however, just one risk factor among a number of others that may play important roles in many different kinds of chronic illness.

In the second post of the series I write about meeting a researcher who accidentally cured an 8-year-old girl of asthma, after inadvertently treating the mother for the effects that early separation had had on her. He has since reproduced these findings in multiple studies and continues to have success in helping kids recover from asthma by treating their mothers. His work showed me how to recognize the subtle events my own mother had experienced when pregnant with me and helped me make sense of my asthma and possibly my ME/CFS as well. It also provided a glimpse of some unexpected approaches that might offer new tools to support and even treat chronic illnesses.

Veronique writes about the large body of research linking subtle and overt adverse life events to risk for chronic illness on her blog Chronic Illness Trauma Studies. She draws from the science of epigenetics, traumatic stress, neurophysiology and research in different chronic illnesses. These offer a view much different from the current “psychosomatic” perspectives that link a history of trauma to implications that such diseases are “all in our heads.”

References

Arbuckle, M. R., J. A. James, K. F. Kohlhase, M. V. Rubertone, G. J. Dennis and J. B. Harley (2001). “Development of anti-dsDNA autoantibodies prior to clinical diagnosis of systemic lupus erythematosus.” Scand J Immunol 54(1-2): 211-219.

Arbuckle, M. R., M. T. McClain, M. V. Rubertone, R. H. Scofield, G. J. Dennis, J. A. James and J. B. Harley (2003). “Development of autoantibodies before the clinical onset of systemic lupus erythematosus.” N Engl J Med 349(16): 1526-1533.

Baldwin, D. V. (2013). “Primitive mechanisms of trauma response: an evolutionary perspective on trauma-related disorders.” Neurosci Biobehav Rev 37(8): 1549-1566.

Bennet, P., M. Rewers and W. Knowler (1997). Epidemiology of diabetes mellitus. Ellenberg and Rifkin’s diabetes mellitus. D. Porte and R. Sherwin. Stamford, CT, Appleton and Lange: 373-400.

Calkins, K. and S. U. Devaskar (2011). “Fetal origins of adult disease.” Curr Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care 41(6): 158-176.

Dahlquist, G. (1998). “The aetiology of type 1 diabetes: an epidemiological perspective.” Acta Paediatr Suppl 425: 5-10.

Dahlquist, G. and B. Kallen (1992). “Maternal-child blood group incompatability and other perinatal events increase the risk for early-onset type 1 (insulin-dependent) diabetes mellitus.” Diabetologia 35(7): 671-675.

Dahlquist, G. and B. Kallen (1997). “Early neonatal events and the disease incidence in nonobese diabetic mice.” Pediatr Res 42(4): 489-491.

Diabetes Epidemiology Research International (1987). “Preventing insulin dependent diabetes mellitus: the environmental challenge.” BMJ 295(6596): 479-481.

Dietert, R. R. and J. M. Dietert (2008). “Possible role for early-life immune insult including developmental immunotoxicity in chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS) or myalgic encephalomyelitis (ME).” Toxicology 247(1): 61-72.

Edwards, C. J. and J. A. James (2006). “Making lupus: a complex blend of genes and environmental factors is required to cross the disease threshold.” Lupus 15(11): 713-714.

Ekbom, A., H. O. Adami, C. G. Helmick, A. Jonzon and M. M. Zack (1990). “Perinatal risk factors for inflammatory bowel disease: a case-control study.” Am J Epidemiol 132(6): 1111-1119.

Ekbom, A., C. Helmick, M. Zack and H. O. Adami (1991). “The epidemiology of inflammatory bowel disease: a large, population- based study in Sweden.” Gastroenterology 100(2): 350-358.

Hofer, M. A. (1994). “Early relationships as regulators of infant physiology and behavior.” Acta Paediatr Suppl 397: 9-18.

Johnston, C., B. A. Milward, P. Hoskins, R. D. G. Leslie, G. F. Bottazzo and D. A. Pyke (1989). “Islet-cell antibodies as predictors of the later development of type 1 (insulin-dependent) diabetes. A study in identical twins.” Diabetologia 32: 382-386.

Klaus, M. H. and J. H. Kennell (1976). Maternal-infant bonding. St. Louis, Mosby.

Knip, M., R. Veijola, S. M. Virtanen, H. Hyoty, O. Vaarala and H. K. Akerblom (2005). “Environmental triggers and determinants of type 1 diabetes.” Diabetes 54 Suppl 2: S125-136.

Lewis, S., D. Richards, J. Bynner, N. Butler and J. Britton (1995). “Prospective study of risk factors for early and persistent wheezing in childhood.” Eur Respir J 8(3): 349-356.

Madrid, A. (2005). “Helping children with asthma by repairing maternal-infant bonding problems.” Am J Clin Hypn 48(3-4): 199-211.

Madrid, A., et al. (2012). “The Mother and Child Reunion Bonding Therapy: The Four Part Repair.” Journal of Prenatal and Perinatal Psychology and Health 26(3).

Maghzi, A. H., et al. (2012). “Cesarean delivery may increase the risk of multiple sclerosis.” Mult Scler 18(4): 468-471.

Maser, C. (1969). “[The perinatal period of multiple sclerosis patients].” Schweiz Med Wochenschr 99(50): 1824-1826.

McKinney, P. A., R. Parslow, K. Gurney, G. Law, H. J. Bodansky and D. R. R. Williams (1997). “Antenatal risk factors for childhood diabetes mellitus: a case control study of medical record data in Yorkshire, UK.” Diabetologia 40: 933-939.

Mead, V. P. (2004). “A new model for understanding the role of environmental factors in the origins of chronic illness: a case study of type 1 diabetes mellitus.” Med Hypotheses 63(6): 1035-1046.

National Research Council and Institute of Medicine (2000). From Neurons to Neighborhoods: the science of early childhood development. Committee on integrating the science of early childhood development. Board on children, youth, and families, Commission on behavioral and social sciences and education. Washington, D.C., National Academy Press.

Nistico, L., et al. (2012). “Emerging effects of early environmental factors over genetic background for type 1 diabetes susceptibility: evidence from a Nationwide Italian Twin Study.” J Clin Endocrinol Metab 97(8): E1483-1491.

Oliveti, J. F., C. M. Kercsmar and S. Redline (1996). “Pre- and perinatal risk factors for asthma in inner city African- American children.” Am J Epidemiol 143(6): 570-577.

Patterson, C. C., D. J. Carson, D. R. Hadden, N. R. Waugh and S. K. Cole (1994). “A case-control investigation of perinatal risk factors for childhood IDDM in northern Ireland and Scotland.” Diabetes Care 17(5): 376-381.

Sandman, C. A. (2015). “Mysteries of the Human Fetus Revealed.” Monogr Soc Res Child Dev 80(3): 124-137.

Schore, A. N. (1994). Affect regulation and the origin of the self: the neurobiology of emotional development. Hillsdale, NJ, Lawrence Erlbaum.

Sepa, A., et al. (2005). “Mothers’ experiences of serious life events increase the risk of diabetes-related autoimmunity in their children.” Diabetes Care 28(2394-2399).

Shonkoff, J. P., et al. (2012). “The lifelong effects of early childhood adversity and toxic stress.” Pediatrics 129(1): e232-246.

Shonkoff, J. P. (2016). “Capitalizing on Advances in Science to Reduce the Health Consequences of Early Childhood Adversity.” JAMA Pediatr 170(10): 1003-1007.

Stene, L. C., K. Barriga, J. M. Norris, M. Hoffman, H. A. Erlich, G. S. Eisenbarth, R. S. McDuffie and M. Rewers (2004). “Perinatal factors and development of islet autoimmunity in early childhood: the diabetes autoimmunity study in the young.” Am J Epidemiol 160(1): 3-10.

Welch, M. G., et al. (2015). “Family Nurture Intervention in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit improves social-relatedness, attention, and neurodevelopment of preterm infants at 18 months in a randomized controlled trial.” J Child Psychol Psychiatry 56(11): 1202-1211.

Xu, B., J. Pekkanen and M. R. Jarvelin (2000). “Obstetric complications and asthma in childhood.” J Asthma 37(7): 589-594.

Yehuda, R., et al. (2013). “Epigenetic Biomarkers as Predictors and Correlates of Symptom Improvement Following Psychotherapy in Combat Veterans with PTSD.” Front Psychiatry 4: 118.

Yu, L., M. Rewers, R. Gianani, E. Kawasaki, Y. Zhang, C. Verge, P. Chase, G. Klingensmith, H. Erlich, J. Norris and G. S. Eisenbarth (1996). “Antiislet autoantibodies usually develop sequentially rather than simultaneously.” J Clin Endocrinol Metab 81(12): 4264-4267.

Thank you, Veronique, for this very detailed explanation of your hypothesis, one which I very much agree with. I came to the conclusion almost 20 years ago that prenatal and postnatal factors were responsible for me getting a diagnosis of fibromyalgia in my 40’s, the only one in my family of 7 siblings. As far as I know the pregnancy and birth were normal but I know that my mother was under severe stress at the time due to financial difficulty, 3 children under 5 and my father away in the country to support us. She then had to live at her in-laws who were very strict. I also know that she left me crying in another room a lot of the time when she couldn’t cope. My main problem is controlling my widespread trigger points which contribute to my fatigue. I also now get asthma and recently found that I have a positive ANA as well as chilblain lupus which I believe is a pre-lupus condition. I have been taking a large dose of pregnenolone for the last 10 years and that has helped a lot but it’s the weather that is my worst enemy, going up and down with each weather front. Have you any suggestions that can help with this?

Hi Tricia, Wow – you’ve connected so many dots (and experienced so many). And most of these are so subtle and unrecognized in our culture even as the research is really beginning to show how and why such events affect our developing nervous and immune systems and more. What I would recommend is working with your nervous system from a perspective aimed at healing “perceptions of threat.” I’ve created a list of therapies I find very helpful on my blog with links to finding therapists around the world in these different modalities. These are just the tip of the iceberg as options to support healing. It’s unknown to what extent healing can happen with chronic illnesses, but I think such approaches can make a huge difference on multiple levels (decreasing or shortening flares and sensitivity to triggers being just one) as they have with me and clients I’ve worked with. It generally seems pretty slow, but then the experiences that shaped us are often long past and have been influencing patterns of response to our environments for a long time.

Thanks for this Veronique. It seems to be becoming increasingly accepted that many of our Western diseases are diseases of sympathetic dominance. I even heard a cardiologist speaking of Heart failure as a disease of sympathetic dominance only a fortnight ago.

Im a GP myself and have had issues with ADHD, and with a chronic pain syndrome. My own observations of my ADHD patients and myself fit a model in which we face difficulty maintaining cerebral perfusion when upright and have to escalate a sympathetic response to prevent that from causing problems. In the context of a musculoskeletal pain problem that is an issue as increased sympathetic tone increases muscle tone (ready to run away).

Now the second observation I have is that the expected outcome of a good attachment relationship can be physiologically defined as the capacity to maintain a balanced state of autonomic activity when at rest, and to quickly and effectively switch to either SNS dominance or PNS dominance at need, then swiftly return to optimal state.

While parenting problems can be an issue and separation at birth is never ideal, we forget that many births are traumatic, and injure both the cervicocranial joint and the underlying brainstem.

At the risk of boring you with my experience – I was one such child, had a significant cervical injury, was whisked off to the 1962 equivalent of a neonatal ICU- and I could NEVER make the rules that worked for other kids work for me. I was clumsy, I was often restless, I was fidgety and I had great difficulty socialising. I was often in trouble in class until the teachers realised how smart I was and how much I enjoyed being praised for it (so they fed me what my mind needed).

Now it is clear from Stephen Porges work that the capacity to engage socially, and to look like you are someone who is safe to be around depends almost entirely on the state of balance of your nervous system (activation of new, myelinated, vagus nerve.

All these problems got worse and worse until I was having severe fatigue, breaking into a sweat at the drop of a hat and struggling to keep my heart rate below 100. As for my blood pressure- I refused to let my doctor look at it. I could concentrate well at the computer, but continually missed things around the house.

Now I’ve looked at this for a long time and I realised that this was an issue of a nervous system that struggled to stay in balance, and was effectively “panicking’ when things started to slip out of control.

About a month ago I found out about transcutaneous vagus nerve stimulation and I set about finding out how to access that.10 days ago I re-discovered the technique of sticking one’s head in a bucket of ice water to turn on vagal tone- and within a week the sweats were gone. About 2 days later the TENS machine I needed to make a tVNS setup arrived, and since then things have only been getting better.I use emWave as a heart rate variability monitor to gauge how its going- along with more informal techniques.

So the first point is- that if we conceive of what a healthy nervous system looks like we have an idea of what sort of intervention is needed. Usually the interventions will be to increase parasympathetic tone.

The second point is that once the system is given the chance to normalise and establish a healthier equilibrium, it will do so rather quickly. I had heard that said- but didnt believe it.

The next point is that virtually all of us who have the sort of decline that you describe and I have experienced, have already got a precedent of many years of good function– so our nervous system does know “how to do it”– it just has not learned how to recover when it is off balance- and the attempts it makes to regain stability end up making things worse- rather like an engine “governor’ which is just slightly out of phase. However we need to remember that good function- as it is potentially easier to get back to than we think.(Full ME/CFS or fibromyalgia with SIBO present a slightly more difficult challenge- but not impossible).

The last point is that it is too easy to assume that just because we had a difficult birth and a separation at birth, does not mean that it is an insuperable barrier. Having gone through a great deal of conventional chiropractic and neuro rehabilitation (vestibular system and cerebellum) I’m clear that the real problem was not the separation at birth it was my physical state– and the only real attachment problem was the one of the attachment of my head on my shoulders.

Andrew,

What an amazing story you share! You provide a great example of how understanding our physiology, such as from Porges and the fight/flight/freeze perspectives, can be so helpful. And how it offers a wealth of potential tools.

This view recognizes our natural drives and underlying capacities towards healthy autonomic balance as well as contributing factors that alter function, including physical trauma as you describe in your birth experience.

What I like about these views is that they can help us look for and test out different therapeutic approaches. I find Porges’ work provides invaluable insights in just this way and I’ve seen similar discussions about vagal stim here on Cort’s blog.

On my own personal journey and in working with clients using my own set of tools, I’ve found that these views can also help us find the pace that fits our unique systems.

For many with chronic disease such as ME/CFS, for example, I’ve found that it helps to go very slowly and at a very titrated, pace. Ie: in tiny “aliquots.” For some of us it appears to be a way of not triggering the old survival patterns that are intelligent but no longer useful defense responses.

Alpha-Gal Meat Allergy IgE Panel blood testing also skin testing for Meat Pork Dairy Chicken & numerous foods in an Allergist Office & AG can cause drops in blood pressure as well & 2 epi pens carried at all times & EDS is actually

ME/CFS Fibro just different Names & multiple copies of Born Genetic copies of the tryptase Gene is also involved testing now carried out in Houston Texas lab here key in Tryptase CNV

Test at http://www.genebygene.com I also believe the Alpha-Gal is also passed on in some at Birth as well all leading to acquired Genetics from both Parents. AG is in everything from

household products to vitamins minerals medicines hospital procedures, blood transfusions vaccines antibiotics home aerosols toothpaste deodorants soaps shower gels shampoos

toilet cleaners toilet paper kleenex hand towels dish soap detergents candle wax car fresheners floor cleaners meats pork dairy flavorings magnesium stearate gelatin all

ingredients from animals. Humans are not supposed to have in their blood Alpha Gal Sugar epitope it is only in 4 legged animals & dolphins & whales even salmon farm raised are fed

beef pellets so to be avoided so is some Tuna processed on ships with Dolphins etc…Cross-contamination in cooking/restaurants & pots & pans with products previously

cooked in & cast iron pans as well need to be changed & no plastic handles…Stainless Steel Pots Pans best no additives Teflon coating is out even steroids have Alpha Gal ingredients so do thyroid medicines…Another blood test that can possibly show something is a (RAST) Panel blood test as well IGE Total can be Normal & not in others. Sugar processed

on bone char contains Alpha Gal so it could be in bread numerous food unrefined white Vegan sugar safer or use none at all…That medicine they talk about being used in Autism &

possible ME/CFS likely has animal ingredients inside so to me it rings alarm bells of if Alpha Gal involved…I have thrown out countless vitamins Cane sugar Brown sugar pain pills all

have AG inside some cannot even tolerate chicken & fowls or fish can have countless additives in them as well even greasy spoon Restaurants are not AG Friendly

Thank you Veronique, for an excellent treatise on the subject of CFS/ME/DM.

I am sufficiently impressed, to Send you some comment/feedback, which is something that I hesitate to do.

Whereas everything you say is correct [at least as far as my limited understanding and experience is concerned], there is one facet of the conundrum which is not understood/realized by most and is not addressed in your treatise.

I will restrict this Note to the bare facts, since delving into the background information would render it unpalatably voluminous.

In brief, stress results in excessive production of reverse T3 from T4, to the point of markedly downregulating the function of T3, sometimes to the point of total non-function of the T3, rendering the subject effectively Athyroid.

This mechanism, entirely due to stress, either Physical or Psychological and whether experienced as a single massive event or via the cumulative effects of multiple hits, results in such reduction of the basal metabolic rate that Lassitude, Depression, weight gain and aberrations of glucose and cholesterol management ensue.

MY SUGGESTION:

[1] Check TSH [optimal value 20, all is well. T3 function is in the euthyroid range.

If the ratio is <20, the person has Functional Hypothyroidism.

[4] Treat Functional Hypothyroidism with compounded, slow release Triiodothyronine:

Do not Rx Cytomel, the rapid absorption from which results in side effects due to T3 "spike and crash".

Do not Rx Desiccated Thyroid [70% T4 and 30% T3], because the T4 will be preferentially converted into RT3.

APOLOGY/correction of error in my previous post:

under “MY SUGGESTION”, it should read:

[1] Check TSH [optimal value 20, T3 function is in the euthyroid range.

If the ratio is <20, the person has Functional Hypothyroidism.

Gervais,

Thanks for your comment and suggestions. I find your point that the thyroid has it’s own physiological patterns of response to stress especially relevant. We have healthy responses to stress throughout our bodies – ie: the HPA shapes adrenaline and cortisol levels, other endocrine responses alter blood sugar and insulin levels; our nervous and other organ systems alter sensitivity of receptors to insulin, sugar, thyroid and other hormones; our pupils, heart rates, gut function all shift, etc…

You describe an excellent nonpsychiatric prescription that is a solution for some people with fatigue and other symptoms. For others it is part of the solution too, as effects of additional organ systems that are also caught in prolonged versions of this stress response are also addressed.

When a direct treatment can be effective, it’s a godsend. And it can be a quick, easy place to start when working with symptoms.

What I wonder about is how our systems get “stuck” in such states in the first place, and that’s where I have gotten curious about contributions from early (and later) experiences and exposures that shape or influence the development and trajectories of our physiologies.

Going well beyond what I’ve introduced in this post, I wonder whether ME/CFS reflects (at least in some of us) getting caught in prolonged parasympathetic dorsal vagal states that Stephen Porges refers to (the older, unmyelinated branch of the parasympathetic nervous system), and which is generally the last step in life-saving physiological strategies when fight or flight are not viable options. I refer here to immobilization / freeze / “hibernation”-type states. Research from other fields, including studies in traumatic stress, suggest that adverse experiences are one mechanism by which physiological states of the stress response can become stuck or caught. Hence my thoughts on working to reverse what can be underlying drivers of altered physiology for some people, especially those who do not respond to meds and other treatments.

This is very good. My experiences with trauma, infection, Type 1 diabetes and potential indicators in my son at birth fit within the process outlined in the article. I can go right down the list and say, CHECK…it is in the monograph I finished last year.

I am really happy you picked this up, Cort.

Glad to hear it Pat! In my case, I was a twin premie put into an incubator in 1959. I don’t think they knew too much about the effects of maternal isolation then (lol). My twin is healthy to this day – but that separation, if it did occur, probably didn’t help….

It’s interesting that research is showing so many factors we didn’t think about can effect us…

Cort – Yeah, I don’t think they knew much in 1959 either! A book from the 1970s by two pediatricians started asking the question about hospital practices after watching what was going on for a few years. We weren’t doing a lot of hospital births until the 1950s (starting in the decades earlier but increasing then).

Out of curiosity, were there many differences between you / your experiences, and your twin’s? For example, birth size, incubator time, health or illnesses at birth or infancy? Some of the research finds that the smaller twin is often the one at greater risk – in part because birth size reflects in utero experiences including stress, and twins don’t always get the same piece of the placenta pie.

Interestingly, I think the short hospital stays after birth these days lead to less separation as compared to the 50ies. I was born in a ward, in 1950. My mother breast-fed and so we had some skin to skin contact. She was the only one in a ward of 36 women who were all hospitalized for 2 weeks of bedrest after giving birth and who fed their babies formula on a strict q 4 hrs schedule.

The idea of “multiple hits ” definitely applies for me – I was Employed in Early Years care and studying for a Degree Qualification and other qualifications . I had repeated virus infections and tried to ignore how badly I felt because I was so ambitious to succeed and be seen as competent.

I also am very glad to see evidence how maternal separation affects health. This is not always understood by parents and Nursery staff . I hope this work find its way into Early Years Textbooks. ( Sadly I am not able to do that job any more ) A very good article I think.

Thanks so much Ruth. It’s a slow process to get this information out there although some changes are happening. The research about the effects of adverse events in childhood (ACEs) is starting to make it’s way into schools, mental health systems and pediatric clinics in the U.S. (I’m not familiar with other countries yet) – although this is more about later hits than about maternal infant separation. And there are some inroads happening for prenatal care and birth practices with WHO birth initiatives and kangaroo care, although still remarkably unfamiliar to most.

Thank you. Very impressed by the whole but especially “Epigenetics is the process by which small chemicals attach to the surfaces of genes and alter their behavior by turning them on and off.” ME/CFS for 40 years, which began with a steady slide downhill for 7 years to disaster, led me to wonder if something was turning on and off. Too often running on red alert and then going off the chart. I am looking forward to reading more of Veronique’sresearch and conclusions.

Epigenetics studies in ME/CFS haven’t had the greatest results yet but they hold a great deal of promise. If ME/CFS is the result of genes interacting with environmental factors (infection, toxin, even maternal separation apparently) then epigenetics could be key…Something shifted…perhaps it was our epigenetics…

Cort and Audrey – I wonder if it will be challenging to track epigenetics in ME/CFS (and perhaps many other illnesses). I suspect there may be many pathways affected that lead to ME/CFS in each of us in different or unique combinations of ways. I think, for example, of Naviaux’ findings of so many metabolic processes that are off and whether each one represents one or more genes that have been affected over time.

Amazing correlations on so many issues. I can recognise a few connections. How about the severe stage of ME where the patient starts to lose the ability to move speak and dies of complete organ failure. I had a severe illness in my teens and was suffering symptoms of ME from then on for 40 years. Only in the last few years has the genetic cerebella atrophy been diagnosed from scans. Could a latent CA be in those of us who develop ME? So many young people are dying of all of this here in the UK.

Hi Alexa,

I wasn’t familiar with CA nor that there’s a genetic component for it. Is it, like many other symptoms, also influenced by experience?

You mention latency. There is evidence for long latency periods before the actual onset of many diseases and the changes are usually not visible for a while (it’s seen in Alzheimer’s with appearance of tangles before symptom onset, for example). So it would seem entirely possible that CA could have an effect on people’s health and evolve slowly / over time.

One of the processes that I believe happens during latency periods is “kindling,” in which new patterns of function are developing in response to past exposures. It’s a well-known phenomenon in the world of trauma / traumatic stress and develops after an event that stimulate perceptions of threat and from which our nervous systems are unable to recover (such as a traumatic event). Over time, experiences that remind our nervous systems – usually outside of our awareness ie: at unconscious levels – trigger the further development of these patterns. At some point we’ve experienced enough “hits” and the kindled process switches into a dominant process that is seen in overt symptoms.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4300794/

“This overview on neurological manifestations of EDS demonstrates a largely unrecognized set of central and peripheral nervous system features in patients with heritable connective tissue disorders. The familiarity that any neurologist has with some of these manifestations when reported in the general population, such as cerebrovascular disease, headache, myalgia and fatigue, poses neurologists in a privileged position for promptly recognizing EDS. Although the global assessment of EDS patients is, by definition, multisystem and often managed by other specialists, such as rheumatologists and clinical geneticists, the neurologist has a high chance of evaluating still undetected EDS patients with a neurological presentation. In addition, while the pathognomonic features of EDS are not historical heritages of neurology, now, we know that a great proportion of the increased mortality and morbidity of EDS patients is linked to the reverberations that a primary connective tissue derangement has on nervous system development and functions. Hence, all practitioners occasionally or constantly involved in the management of EDS should be better aware of the neurological manifestations of this condition on both clinical and research perspectives…”

I’m sorry but this hypothesis is simply a fancy continuation of the medically popular blame-the-patient’s-thinking theory. Consider that many, many more people experience fetal or infant separation and/or trauma than have developed chronic illness.

I see here a doctor parroting the currently fashionable medical view of ME/CFS perhaps as a way to recover a respected career.

Veronique, please note that many with ME/CFS also have Ehlers Danlos or similar connective tissue disorder genes. If our immune system is housed in our connective tissue (and the ATP production system relies on adipose (also connective) tissue, then it follows that an overload of infection, stress, mold, petrochemicals, etc. will tip the balance of homeostasis to overload. As of March, 2017, the nosology for Ehlers Danlos Syndrome (EDS) recognizes chronic fatigue and POTS as a symptom,and unfortunately recommends GERD and CBT.

You’ll never help yourself by selling us out within your profession. However, if you are brave enough to spearhead low hanging fruit in research, such as a study looking for connective tissue disorder genes, especially EDS in chronic fatigue patients, you could bring yourself much fame and respect within your profession and a way to a continuing income stream.

HI Aquafit,

I haven’t studied EDS but a quick look online states “The condition is inherited in an autosomal dominant manner.[2] “ So I’ll start by saying that I’m not arguing that genetically-based diseases are caused by stressful perinatal events.

I’m also not arguing that there are not a complex number of things that increase allostasis and load to affect risk for many chronic diseases, especially in the period before onset.

What I do repeatedly find is that early experiences influence all kinds of physiological processes, very possibly connective tissue function as well. And maybe it doesn’t’ affect EDS – I’m not familiar enough with that body of study.

The emerging research showing that life experiences influence and shape our genes through epigenetics, however, is not “blaming the patient” – in fact I see it as quite the opposite. No one chooses to experience stressful events – including babies.

What I’ve found over the years from research in other chronic diseases is that the exposures during the embryologic period before birth and when our organ systems are developing at great rates, including in infancy and childhood, have an impact on long-term health. Similar to the way thalidomide exposure had a very specific effect on the organ systems that were developing at the time of exposure. Exposure to stressors and traumatic events has an impact too, although much more subtle.

This article only introduces a set of risk factors. Early exposure to perinatal stressors – both in people who have a genetic predisposition, as well as in many who do not – is probably not enough to cause chronic illnesses, but instead may initiate / increase risk for some people that never progress to symptoms or disease.

It appears to be a matter of whether we experience additional “hits” (including the kinds of risk factors you mention). Such exposures are found to interact with genes and are believed by many to be necessary (in diseases such as type 1 diabetes as an example), to accelerate and perpetuate the pathological process that may eventually become an overt expression of disease.

I find it of interest, to address another point you make, that 50% of adults in the United States have a chronic illness of some kind. One of the findings I’ve seen in the research is that perinatal events affect risk for different kinds of illnesses, not only ME/CFS or T1D or asthma.

I agree that there is a difference between genetically ingrained characteristics such as EDS and those that are caused by polymorphisms that are gradually developing over time and, I believe, also inherited from several generations back. I believe that it is the polymorphisms that cause chronic disease and that is why the experience differs between individuals. I also believe that the abnormal brain pathways created by these inherited pathways at birth are pretty much difficult to change whereas the pathways created by later polymorphisms may be easier to shift. I have found that taking pregnenolone has helped to a degree in moderating the sympathetic nervous system. It is certainly not a cure but has alleviated the severity of my condition.

I just don’t understand the blame the patient idea – particularly if its a baby. If something happens to a baby in the womb or after birth – how can you hold a baby responsible?

For me these studies, like all studies of their kind, represent increased risks. Not everyone experiencing maternal separation comes down with Type II diabetes. Nor does everyone with adverse childhood experiences come down with an autoimmune disease. Nor does everyone who comes down with mono get ME/CFS or multiple sclerosis later in life.

These are complicated and complex diseases that sure have many factors we don’t know about yet. I was struck that to get complex regional pain syndrome you probably need two things – an injury occurring at the some time as infection (!). Who knows what primes someone to get ME/CFS? I imagine a boatload of possibilities exist.

I’m complete agreement with this. Everything stated can be pinned down to infectious processes.

This is the most inspiring piece of thinking about chronic illness I ever read. It’s written very clear. The presented ideas are both straightforward and an absolute wonder of combined thinking outside the box, creativity, linking unlikely events and knowledge and last but not least backing this up with experimental data. That is no small feat by any standard!

I dislike to say this: your disease is a great personal tragedy for you and your environment. But what it inspired you to do is beyond words. Thanks many times for doing this under such difficult conditions your illness presents! I find it hard to imagine this is only part one of your work. Thanks once more!

Hi Dejurgen,

I agree with you that my disease has inspired and motivated me – probably much more than anything else ever could have even if I’d simply been interested in learning more about chronic disease. It’s been one of the most helpful, powerful tools I’ve had to testing out these hypotheses, seeing whether they help make sense of my symptoms / flares / triggers, seeing just how incredibly subtle the events that affect health can be (and hard to recognize). It’s also been invaluable for exploring whether addressing specific types of exposures helps with my symptoms (they do and have). While being debilitated has sucked in so many ways, having this illness has also been a remarkable gift for me on this journey. I’m so glad it comes out clear and straightforward!!!

The disease has inspired a lot of creative thinking and speculation. We’ll see more of that in the next blogs on hypotheses in ME/CFS and FM.

About 4-5 years ago, I watched the “Ghost in Your Genes” video you mention and it was fascinating. It introduced the field of epigenetics to me, as well as how what our parents experienced could affect us. I know my mother went thru a period of extreme emotional distress when she was pregnant with me, which made me wonder if it was a factor in this dreaded disease. Also about 4-5 years ago, I posted on this website that I felt the problem living with ME/CFS was rooted in our brain’s misconception of what constitutes a ‘threat’. It simply goes WAY overboard when responding. Once I began following this theory, I could always determine what initiated the crash, and sometimes it was caused by background thinking – a subconscious thought. In any case, being aware of this theory has greatly affected my ability to deal with the illness. Don’t get me wrong. I am not suggesting ME/CFS is all in our heads. I think there is an underlying irritant which keeps us on the fence, healthwise, and it only takes another small issue to push us over & make us crash. In my opinion, the irritant will prove to be Monsanto’s RoundUp pesticide. As I understand it, RoundUp messes with the bug’s mitochondrial DNA to kill it. It isn’t something that can be washed off like most pesticides, as it’s in the DNA now. Monsanto tries to silence or discredit researchers studying RoundUp, but there are studies from the NIH that describe the dangers, which seem so prevalent in ME/CFS symptoms. RoundUp was introduced in 1974, only a few years before the Incline Village break-out. Once properly studied, I think RoundUp will become the new tobacco in the courts. Here’s a 6-minute video about ME/CFS & mitochondria……. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fqCM4LkKGEE&feature=sharehttps://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fqCM4LkKGEE&feature=share

Hi Per,

I agree that toxins like RoundUp have all kinds of effects on our bodies and nervous systems and are likely one of the many complex factors that influence risk, at least for some. It seems that at some point we cross a tipping point into disease when these risk factors add up beyond a certain point.

I listened to the video on the familiar topic for ME/CFS and wonder if mitochondria are the ME/CFS equivalent to insulin in type 1 diabetes. Mitochondria may be affected by toxins. They may also be directly regulated by a nervous system operating in a different state of threat awareness. Maybe one day we’ll find antibodies or biomarkers for this for our disease.

The way I would think of what you just summarized so beautifully is that early stressors imprint and alter our genes and nervous systems.

Some of us may become more sensitive to toxins like RoundUp. Others to infections. And others to additional stressful experiences. I think of all of these as “triggers” and fully agree – it’s not in our heads. It’s in our nervous systems and physiology.

Roundup also contains Alpha Gal animal ingredients & countless fruits & vegetables have also animal wax ingredients so that

bite in the apple with AG may not keep the Doctor away &

Peanuts especially ones shipped from China have beef flavoring

added to them & Planters Peanuts contain ag ingredients so does Heinz Ketchup made with animal blood flavoring so do countless cigarette filters from Pigs blood

I can sure imagine that RoundUp will turn out to be a significant irritant to human physiology. And that it could be involved in causing ME/CFS.

But I thought RoundUp was an herbicide, not a pesticide.

Cort, I appreciate your neutrality in journalism and your quest to provide a forum for everyone who feels they have a valid ME/CFS theory. I also appreciate that you’ve provided a forum for others to critique theories put forward.

I could have worded my opinion more clearly; I didn’t mean blame the baby but in this case blame the parents or the surrounding environment, etc. What I feel Veronique puts forward is a theory which ends up in CBT and maybe GERD. Bottom line. As a doctor, she’s well aware of the position of worldwide Colleges of Physicians and Surgeons regarding chronic fatigue, and that is to discourage medical research and keep it in the purview of the psychiatric field.

For many years NIH would not give funding to researchers to examine the possible benefits of marijuana. Only the harms. Thus the government created the impression, for doctors and the public, that marijuana had no beneficial, especially medical, benefits. I do feel the same has happened in the area of chronic fatigue and more recently, as we have aging baby boomers, chronic illness.

This is not about blaming parents either (post 2 in my series describes how these early stressors influence maternal physiology and capacity for bonding that are outside of their control; and how these effects interact with babies to affect their physiology as well; post 3 shows how these effects can influence genes rather than psychology; parents don’t choose stressful experiences such having a premature baby, a complicated delivery, or other early stressor). Regardless – the point I want to make is that such effects alter nervous system function rather than being psychological.

Nor is it about a psychiatric or psychological or psychosomatic view of ME/CFS. I’m neither a fan of CBT nor graded exercise nor the PACE study.

These concepts are, however, on that challenging line that looks at how emotional experiences affect our physiology. That, in itself, is certainly tricky territory because it can make some researchers / family / friends etc think we’re saying it’s in our heads or done on purpose or because we’re weak or lazy or not trying hard enough or faking it etc.

But now that we are learning how epigenetics alter gene function and expression, it’s helping make sense of why risk factors are so complex. And why it’s truly not in our heads.

Ultimately, I DO think there are many kinds of approaches that may help, including therapies – but these are approaches that facilitate nervous system patterns of regulation and reducing nervous system based perceptions of threat that are not about our psychology. These are not approaches aimed at will power or pushing through or thinking positive etc… It’s more complex than that – and also often a much slower of a process.

Thanks Aquafit. I appreciate your reply. I don’t know where Veronique’s hypothesis will end up but I suspect that it will end up in some sort of behavioral practices. I don’t mind that. I suspect behavioral practices may be helpful in many diseases. I remember my mother with Sjogren’s Syndrome doing hypnosis tapes her doctor suggested to try and get it under control. I don’t think it worked but if we have a revved up or dysregulated autonomic nervous system some behavioral practices that relieve stress might be able to give it a nudge in the right direction. I would note that Veronique has improved but that she still has a long way to go before being healthy. That’s kind of what I expect from these kinds of practices.

Your mother had Sjogrens? Cort, do you have Ehlers Danlos or other connective tissue disorder genes that you know of?

BTW I’m getting none of these posts in my email.

Aquafit, you are so right!

Why again give a forum here to such useless theories!

Patients with ME need biological research for a possible cure.

To what progress for patients can such theories lead?

For sure we need more biological research and that is where the cure will lie but as Veronique noted she’s used techniques based on this findings that have helped her improve.

Veronique, I understand the nature of your discourse when you say that you’re examining “emotional experiences that affect our physiology”. When you say “tricky” you mean that it makes patients and families upset. Why does it make patients and families upset? Because you’ll be contributing to the large NIH funded body of evidence that insurance companies and doctors are able to point to which keeps investigation and therapies in the psychiatric and not medical field. Whoever is or is not to blame within your concept, when chronic fatigue is diagnosed as a person’s emotions affecting their physiology it discourages further medical investigation into a medical ?rather than pharmacological₧ cure.

If there is a behavioural tendency amongst ME’ers, I would say from vast experience that it’s extreme kindness and tolerance.

Further on the thought of experiences in the womb causing epigenetic changes, I find it very interesting that Down’s Syndrome (a condition involving connective tissue) clusters have been shown to be caused by:

Exposure to radioactive waste or radiation

Proximity to waste disposal sites or landfill sites

Exposure to smoke (especially if the mother smokes during pregnancy)

Exposure to infective microorganisms and bodies (including viruses)

http://www.medic8.com/healthguide/articles/downssyn.html

How many more mothers and fetuses are exposed to petrochemicals in food in the form of pesticide residue, grooming products, airborne pollutants, etc? Malathion is just one pesticide (made from petrochemicals) that has been shown to affect collagen. If our immune system is housed in our connective tissues, it’s worth investigating IMO how everyday exposures may be predisposing our genes to ME/CFS.

While it is true that scientific studies have given CBT and GET a foothold I don’t think anyone anymore believes they can cure ME/CFS. I want to point out that those studies were not done by the NIH – the NIH, in fact, has funded only a few CBT type studies. Almost all of those studies come from the U.K. and the Netherlands.

With the IOM and AHRQ reports poo-pooing CBT because of the use of the Oxford criteria, the U.S. is actually, in a way, leading the fight to get those therapies either dismissed or put in their rightful spot. I don’t believe that the CDC recommends them any longer.

The vast majority of the ME/CFS studies, the NIH funds are, thankfully, focused on pathophysiology.

Thanks Aquafit and Cort.

Understanding the genetic and pathophysiological underpinnings of any chronic disease is key, including and especially ones like our own that is so misunderstood.

But I think it will ultimately be about more than behavioral practices. There are differences between stress and trauma (more than I can attempt to get at here). And you can’t just practice stress reduction or stress relief or meditation or “regulation” to shift the physiological effects of trauma (even as it is sometimes enough for some people).

I think that’s what so complex about all this. The conversation is helpful in keeping me thinking about how to present it / think about it!

Let’s ask Veronique a couple of questions.

When an MD suspects Chronic Fatigue Syndrome, is the protocol to refer to psychiatric care or is it not?

If early stress/trauma is found to cause the bodily response of chronic fatigue syndrome, will this confirm for doctors that Chronic Fatigue Syndrome belongs in the purview of the psychiatric field and discourage them from further physiological investigation of symptoms they perceive as related?

Aquafit, The mistaken view of ME/CFS as a psychological disease has caused pain and problems for many. I recommend being selective about if or when you tell an MD of any history of stress, trauma or emotional symptoms.

There has indeed been research and publications stating our disease is psychosomatic etc. That’s an outdated, inaccurate model. I refer to the emerging understanding that gene-environment interactions influence risk for chronic illness such as type 1 diabetes. New ME/CFS research, such as what I regularly see here on Cort’s blog, is using incredible new tools and heading in new directions too. Let’s learn from research in other chronic diseases such as type 1 diabetes and asthma where we can, and be open to what the science of epigenetics shows us. It could turn out that we each have unique pathways to this disease as well as individual pathways to recovery.

Sorry, left out a found cause of Down’s Syndrome in my previous comment taken from the linked website;

Exposure to pesticides

This article and the responses to it are really mind boggling! I guess that everything that happens to us starting at conception (and before) influences the course of our lives!! Is this anything more than saying that each of us is unique??

Am still waiting for information (research) that outlines commonalities that underlie the ailment we call ME/CFS.

Hi Seesir,

Yes – it truly is mind boggling, isn’t it?

I’ve only found one article (Dietert) suggesting a similar link between perinatal stressors and risk for ME/CFS so far, looking at how early events influence endocrine, immune, and nervous system function among others.

There is one other article I know of, which comes from a similar perspective about long-term effects of these early events, but the focus on ME/CFS in this latter study is as a “stress-related disease,” and I have similar concerns about this view as voiced in this thread.

That said, studies are finding that early events affect risk for all kinds of long-term health issues, including mental health conditions and that it’s not because either of these are in our heads. It’s increasingly understood to be due to how early experiences shape nervous system and other physiological pathways, and epigenetics etc, into unique directions. I especially like this summary article about these common pathways by Harvard’s director for The Center of the Developing Child.

It took me years before I started to recognize links between seemingly ordinary events in my own early life and my chronic illnesses. It wasn’t until I experienced these effects, saw the links more directly while working with my own nervous system patterns, and began to identify some of the very subtle triggers that I realized they had affected my own health as well. I describe these insights in the second post about perinatal risk factors for asthma, which I also have had and am almost entirely recovered from.

Seesir, the commonalities we all have are chronic fatigue and problems of the nervous system. Doctors already recognize that. Because of concepts like Veronique’s have made it into the protocol for ME/CFS, most doctors will write you off when it comes to medical investigation and instead send you to a psychiatrist. Not, these days because you have a psychological problem, but an “emotional” one.

I sat behind Cort at a conference once. Cort was listening to a Nancy Klimas and diligently writing for this website. After a time, Cort’s head started to bob. The nod of someone who’s fighting sleep. Now, currently, the medical protocol would be for Cort to see a psychiatrist who would help Cort “understand” the root of his problem. I however, feel that it’s a musculoskeletal problem (in part) and when this happens to me I take the advice of a few people on the inspire.com Ehlers Danlos website and I fold up a newspaper in a scarf and voila, I get a few more hours out of my day when my neck is supported and the nerves and blood vessels which travel through the foramen magnum are not being pinched.

Further, and this is a rhetorical question; what do you think has a greater influence on your nervous system – early childhood events which you can’t remember which supposedly affected your emotions or chemicals which are toxic to the nervous system?

http://www.ejnet.org/plastics/polystyrene/health.html

“The fact that styrene can adversely affect humans in a number of ways raises serious public health and safety questions regarding its build-up in human tissue and the root cause of this build- up. According to a Foundation for Achievements in Science and Education fact sheet, long term exposure to small quantities of styrene can cause neurotoxic (fatigue, nervousness, difficulty sleeping), hematological (low platelet and hemoglobin values), cytogenetic (chromosomal and lymphatic abnormalities), and carcinogenic effects.[1,2] In 1987, the International Agency for Research on Cancer, Lyon, France, reclassified styrene from a Groups 3 (not classifiable as to its carcinogenicity) to a Group 2B substance (possibly carcinogenic to humans).”

2. B.J. Dowty, J.L. Laseter, and J. Storet, “The Transplacental Migration and Accumulation in Blood of Volatile Organic Constituents,” Pediatric Research, Vol. 10, pages 696-701, 1976.

What did you mean by “exposed to vitamin d”? Thanks

Thanks for catching that error – I meant to say low levels of vitamin d.

T1D, much like ME, is caused by coxsackievirus B infection. In T1D, the B1 serotype appears to be the major cause. A vaccine is being developed, which will in time prove this connection and may also thwart many cases of ME as a side effect.

It may be academically interesting to wonder about all sorts of risk factors, but in the end if we can remove the actual infectious trigger that causes these diseases, the risk factors won’t matter much anymore.

Weyland, I have no problem with single causes and quick fixes if we can find them.

hi thankyou f or this post it realy caught my attention.

so much of it pertains to my expericene. i was dagnosed in august of 2001 w CFs but realized that it had been coming on for years and i alsways thouyght it was the flu.

i hve terrible flare ups i call them creashes which correlate diredctly from stresses in fact this list of posts stressed me out when a post attacked the dr as looking to get somem accolades and become famouns just for this hypothesids.

damn

i was a difficult forceps and then c section birth in 1960. and was in-utero for a very stressful pregnancy my mother marred a very violsent alcoholic and i was left alone and cried a lot and not picked up etc. much childhood stress and later my own experiences in college with sexual assaults and alcohol abuse but caught that qyiclkly and then at age 23 I was given several large- with a “gun syringe” heavy duty injections for being deployed overseas when i married into the military. I was often alone and stressed and tired slept and slept. years of poverty bad nutrition and hard work followed. as a single mother really felt the exhaustion and always htoujght i had the flu. finally crashed to the point where i was as you mentioned earlier, could barely talk not able to sleep extremely low blood pressure, lymph nodes swollen, lights hurt my eyes, low body temp, horrible headaches and incredible pain all over my body which is why I thought it was def neurological and wondered if there was a correlation to the stress/diet/pushing my body so hard working several jobs 7 days a week and living with a raging new spouse and angry teenager.

I could go one with the dramas that is my life experienced but that is the jist and so as far as pre gentetics- my father was def abused in an orphange during the depression and developed alheizerms and died at 69.