After 11 years of marinating in chronic illness, my ability to work has all but evaporated and I have entered the world of full time disability for the first time in my life. This time of year would normally mark a return to university life after the summer break. Right now, my professor colleagues are putting the final touches on their course syllabi or perhaps are working madly to finish a manuscript before the semester starts, when their attention will scatter as they return to their four jobs in one: educator, mentor, researcher, and administrator. For now, I have a sole focus: to try to improve my health.

As someone who has worked hard since the age of 11, I can’t imagine more than a few weeks going by without engaging in some sort of industry. So far my full time disability has only lasted three months, so the memory of working life is still fresh. But over time, my CV will gather dust, and many years will have passed. I was saddened recently when I read a story about another person with my illness – myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome, or ME/CFS.

In her piece, she reflected on the six years that had passed since leaving her job as a faculty member and her efforts to find meaning in her new life as a sick and disabled person. The uncertainty that chronic illness brings to one’s career prospects, along with all else in life, is bracing.

I ask myself daily, “What on earth am I going to do with myself now that I am disabled and not working?” But harder still, if I am honest with myself, is the knowledge that my career as an academic is over, and has been over for the past five years, . At first, I could manage my job by spending all of my non-working hours in bed. Then I had to drop my research program, which is so critical for a scientist. Next, I had to minimize my teaching schedule. Eventually, I could not even do administrative work to my satisfaction. One cannot simply drop out of academia for a number of years and hope to return. It does not work that way. It is all or nothing.

Sowing the seeds of chronic illness

When I was 20, I decided that I wanted to be a conservation scientist and save Central American rainforests. I dreamed of a career that brought together my love of science with my passion for protecting biological diversity. I started my journey traveling solo through war-torn Guatemala, Honduras and Nicaragua, and ended it in Costa Rica, where I quickly decided that the tropics were not for me, at least not for field work (I hate being hot!). Pursuing a Ph.D. in population biology at the University of California – Davis seemed the perfect opportunity to combine two of my favorite things – ecology and travel to exotic places.

My Ph.D. program was one of the more prestigious, rigorous and probably sadistic ones in the country, but perhaps everyone feels this way about their graduate school experience. The extreme stress of graduate school, combined with a deep insecurity about my abilities, led me to make some unwise choices about my health. I survived on roughly five hours of sleep a night and fueled myself with nothing but carbohydrates and caffeine, all in the name of trying to prove myself (to myself mostly). This would go on for weeks until I would crash and start all over. Little did I know that I was sowing the seeds of chronic illness.

My dissertation research took me to South Africa, a place that provided sanctuary from the stress and trauma of graduate school and a place to grieve my mother’s sudden death from a brain aneurysm during my junior year of college. I would spend the first month of my 9-month field stints in a remote and rustic cabin nestled in the Kogelberg Biosphere Preserve, the crown jewel of the fynbos biome, and one of the world’s biologically diverse hotspots.

My field season started at the onset of the cool and rainy season, allowing me to leave behind the searing summer heat of California’s Central Valley. As the winter fronts blew in off the Atlantic, I could feel my nervous system settle down from the high stress of being a Ph.D. student. Slowly, the solitude of the cabin allowed me to relax back into my own skin. Eventually, dear friends from the University of Cape Town came calling, bringing me red wine and olives from the South African town of Stellenbosch. Their company restored my ability and desire to connect with fellow humans again.

Many people with ME/CFS can pinpoint the precise moment they fell ill. On the evening before returning to the US, I struggled to pack up and clean my cabin. My limbs were heavy, my brain was thick, and I was fatigued in a way I had never before experienced, even with the flu, yet nothing else seemed to be wrong. During the flight home, I was delirious and thankfully had a row of four seats to myself.

After spending a few days in bed nursing my jet lag and trying to recover from whatever bug this was, I mounted my bike and attempted to ride to my office at UC Davis. A third of the way there, I realized that I was in trouble. I was too far from the university and too far from my house. Somehow, I pedaled home and eventually drove to the student health clinic to be evaluated.

Within moments I had an answer: at the ripe age of 32, I had mononucleosis. Before leaving the exam room, the doctor told me that, “Sometimes people don’t recover from mono, especially if the onset is later in life. And you may be more likely to develop lymphoma, so keep an eye on that.” Who ever heard of mono not going away and causing cancer? I found that to be rather alarming but promptly put it out of my mind.

My recovery was difficult and slow, but after six months I was back in South Africa and able to work 12-hour days in the field. Occasionally, I would wake up with familiar feelings of crippling fatigue, a mild sore throat and swollen glands. I called these my “monoecious” days and stayed home. This happened 2-3 days a month, but otherwise I was managing.

Friends and colleagues who spent their holidays nearby looked after me well and invited me to dinner after my field days. After my convalescence from mono back in California, one of my South African friends told me that she once had ME, too. ME? What the heck is that? I had never heard of it. She said she had developed it after a bout of glandular fever, which I would eventually learn was the name used for mononucleosis in South Africa, as well as in most other English-speaking countries. I thought to myself, “I’ve never had glandular fever, nor do I have ME, whatever that is!” Despite this, we often discussed her experience with the illness, how she was bedbound for the first four years of her son’s life. She shared what worked for her in managing her illness – magnesium, primrose oil, etc.

I remember going to the pharmacy to purchase supplements and kneeling down on the floor in the aisle, pretending to get a closer look, feeling so drained. There I was, thinking this would be behind me once I took the supplements that help ME, even though I didn’t have ME. Little did I know that she was foreshadowing the road ahead.

An illness takes hold

Six years later, and just after starting my faculty position, I sat on an examination table, legs dangling down, resisting the urge to lie back and rest. The long wait gave me time to reflect on my situation. Why was I feeling so sick? Was it because I was still breast-feeding and co-sleeping with my son? Why did I feel like I had mono all over again? After giving birth in 2005, I quickly realized that being a senior scientist for The Nature Conservancy was no longer going to work for me. I was traveling 3-4 nights a week and managed to lug around my infant son for the first seven months after he was born.

When a position was offered to me at Sonoma State University, where my husband was a professor, I felt incredibly fortunate (or so I thought). But I had never taught beyond serving as a TA in graduate school, and I had three new courses to develop on the fly. This meant having to work late into the night writing lectures and grading, only to co-sleep with our son who was still waking every hour to nurse. By November of my first semester, I hit the wall and was as sick as I was when I had mono.

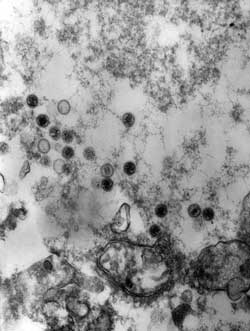

My physician at the time was concerned and suggested that I had chronic Epstein-Barr Virus (EBV). She said I could try an off-label use of acyclovir, a drug commonly used to manage herpes simplex infections, but studies in the 1980s had shown that it was not effective for use on other herpes viruses like EBV and there was even doubt that EBV could be a chronic infection in the first place. I tried acyclovir for a month but it did not help, and I figured it was a stretch, especially with little evidence to back the approach. It was the first time I felt that my being a scientist placed me at a disadvantage in dealing with this illness. We tend to place far too much faith in institutions and are prone to believing that evidence-based medicine is the answer (it might be if your particular disease is well researched, but mine most certainly is not).

A new doctor (my insurance had changed) tested only my thyroid and vitamin D levels and conferred the “ignoble diagnosis of chronic fatigue syndrome.” He added that there was nothing I could do about it except to wait for another 10-20 years for science to inform us. I foolishly believed him for five years.

I kept returning to him for seemingly unrelated issues – foot pain (are my arches collapsing?), stomach pain and queasiness, a “sore” liver, costochondritis, insomnia, and of course the fatigue. After reaching the end of extensive gastroenterological investigations with nothing turning up, the lightbulb went on. This was a systemic disease and all of my symptoms were somehow linked. I soon found a private practice in my town specializing in complex chronic illnesses.

Starting in 2011, I began a journey down the rabbit hole that is Lyme disease. I had to park my scientist credentials outside the door as I embarked on treatments that most would raise an eyebrow at, including years of IV antibiotics and many naturopathic remedies. I never had a positive Lyme test. Despite these interventions, the overall trajectory was downward (but with enough positive responses along the way to keep going). I was desperate and was being marginalized by health care professionals in the mainstream. With Lyme disease, at least there was a real enemy to fight – even if it was an imagined one.

Eventually, I decided that my problem had to be more viral in nature, rather than bacterially-driven Lyme disease, given how my illness started with mono. I had had seemingly enough antibiotics to treat any bacterial infections. I identified two ME/CFS specialists, thinking that they would be the best doctors to address a chronic viral problem, with the full understanding that the problem was likely much deeper in the immune system. At this stage, there was growing evidence supporting the use of antiviral medications for treating ME/CFS, but some of these drugs were expensive and I knew I would need a specialist to access them affordably. I rolled the dice and was fortunate to get to see one of the leading ME/CFS specialists. It was only then that I learned that I had been missing a vitally important piece of the puzzle, because I had been treating the wrong illness. Although both Lyme disease and ME/CFS share a long list of non-specific symptoms (symptoms that can be ascribed to any number of conditions), there is one feature that sets the two illnesses apart: post-exertional malaise, or PEM, which is a worsening of neuro-immune symptoms caused by exertion.

ME/CFS: a disease of the immune, nervous, and energy systems

ME/CFS is the only disease for which exercise (or any form of exertion) worsens the condition. This runs counter to most medical and popular advice on how to stay healthy. When ME/CFS patients are delayed in getting a proper diagnosis, they run the risk of overdoing it, and in doing so, making their condition far worse.

Much of this happens at the hands of physicians, who insist that exercise is the answer to our fatigue. It is well documented that most exercise harms people with ME/CFS. Sadly, progress in ME/CFS research was largely thwarted for five years by an influential group of British psychiatrists who published a study in the Lancet asserting that exercise and cognitive behavioral therapy were effective treatments for this disease. Subsequent reanalysis of the data revealed serious flaws in the paper, and the U.S. Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has removed all mention of this study from its website. Too much evidence has mounted for anyone now to refute the fact that ME/CFS is a very serious neuro-immune disease, yet the legacy of this study continues, especially in the United Kingdom.

It is not entirely understood why our symptoms worsen with exertion, but one reason is that the anaerobic threshold is substantially lower in people with ME/CFS, which means that we burn fuel inefficiently much of the time and feel like we have run a marathon from something as seemingly harmless as rolling over in bed. Even using my brain to write this essay will cause PEM. All those years of overdoing it with this illness have taken their toll.

Most doctors do not appreciate the fact that energy metabolism is severely impaired in ME/CFS patients because it is not taught in most medical school curricula. This creates many problems for patients. Because this is a systemic illness, we often find ourselves being referred to specialists who may or may not have experience with this disease. This often puts patients at further risk because pressing health concerns are routinely dismissed. It is a bit of a lottery; occasionally you happen upon a doctor who is curious, listens well, and wants to help, even though they do not know much about this disease.

I was lucky this past spring, when I was referred to the neurology department at Stanford University. Although they might not have much direct experience with ME/CFS, they understand one of the more debilitating components of this illness – disorders of the autonomic nervous system (ANS), also called dysautonomia. Preliminary investigations have shown that my blood pressure does not respond as it should and my adrenaline spikes with little provocation. My heart rate increases about 30-50 beats when I stand up and it is much worse on days when I struggle with adrenaline surges. It takes very little provocation to send my heart rate to 150 beats per minute (bpm) from a resting heart rate of 55 bpm, and it can take a day or two to recover from such spikes. Lately the spikes happen daily, if not multiple times a day, leaving very little time for recovery.

An impaired ANS also makes eating and digesting difficult, and greatly affects sleep patterns, temperature, and sweating. All of this means I cannot handle much stress, have a low body mass index, and now use an electric wheelchair at home to minimize the rapid and sustained rises in my heart rate that I experience when standing. Fortunately, there are some helpful treatments to manage this aspect of my condition.

ME/CFS is a spectrum illness, meaning that some people are only mildly affected while others are severely impacted to the extent that they are bed bound, unable to speak or move, and may require nutrition through feeding tubes. People can remain in this state for years before the disease finally takes them from B-cell cancers, digestive failure, heart failure, or more likely, suicide. I started out as moderate, but am now moderate to severe, with periods of being on the more severe side due to the fact that I was unaware of the dangers of PEM and pushed through my fatigue for years. There are many aspects of this illness that are challenging for me, but the hardest part is that I now live from hour to hour most days, and some days it is more like minute to minute. I never know when the rug is going to be pulled out from underneath me in the form of a minor or major health crisis.

Delays in diagnosis are probably one of the most substantial barriers facing people with ME/CFS, and that was certainly true with me. This happens because we do not yet have a good diagnostic test, apart from a brutal 2-day exercise test that demonstrates significant drops in aerobic function the day following exertion (this happens in no other illness that has been looked at). We lack a good diagnostic test because funding from NIH has been woefully inadequate, probably owing to the damaging views about this illness peddled by psychiatry. Why do most major illnesses have such a dark history of blaming the patients? How can we be living in the 21st century, with the technology we possess at our finger tips, and still not understand a disease that is more than four times as prevalent as multiple sclerosis (MS) and that carries a quality of life on par with late-stage AIDS and congestive heart failure (CHF)? I can attest to this after witnessing my father suffer through CHF – we were eerily well-matched during the last four months of his life, hobbling around together on our walkers.

Now that I am at approximately 20% of my former functionality, I have come to see my disability as a gift, one that will allow me to do the pacing I need to stay in my energy envelop. I use a heart rate monitor like a shock collar to remind me when my heart rate is above a safe threshold for me. This usually translates to being in bed for the entire day, getting up only for essential things like eating and going to the bathroom, and I use my electric wheelchair for these tasks. Showering has become a luxury.

My swan song?

My South African friends asked what I wanted my swan song to be, or my last act before returning home, a final adventure of sorts. I chose the Kalahari during the rainy season and went there with some of the finest people I know. The images from that trip are still seared into my brain. Like watching black-backed jackals come sniffing around while preparing a poike (a stew cooked outdoors in a cast iron pot with legs). I will never forget the backlit skies with thunderhead clouds framing the delicate new growth brought on by the rains. The yellows, greens, and greys of southern Africa during the rainy season can’t be found anywhere else. My illness makes these experiences even sweeter now.

I remain hopeful that being a professor is not my last professional act, but the varied and complex nature of my illness means I am no longer able to work, in any capacity, and likely won’t be able to for the foreseeable future (or until effective treatments are developed). I am still the same me. My brain, when working, is still full of curiosity, and I have a strong desire to serve and connect with people. This is especially hard for me because in a better moment, I can almost imagine tackling a project. I pick up an idea, make progress, then crash. It can be two months before I return to it again, if at all. There is a virtual graveyard where many fun and creative ideas and dreams of mine have gone to die. With my brain fog, ideas float around me in slow and random motion, as on a space ship with no gravity. Occasionally I reach for an idea and occasionally I catch one. I am surprisingly OK with this process. But the truth is that even these ideas may never take flight.

Working adds diverse experiences to life – stimulation, connection, belonging, purpose – and stepping out of the workforce narrows opportunities that greatly enrich life. We are hard wired to work. How do you convey to someone the sadness that comes from having to put down a dream career for which you worked so hard? To go from being a respected and valued community member, to having no community? We recently had to leave our home in the California oaks because I can no longer work. I do not know anyone in our new town and do not have the usual ways of growing a community here because I am too sick and it is too late to meet other parents at my son’s school or to make friends at work. Recently, I sat alone at the school yard, watching my son run a race, tears streaming behind my large, dark sunglasses. I felt so alone being a spectator to all of the parents standing around, talking, sharing, doing what parents do all the time at schools all around the world.

One of the things I am finding most challenging now that I am no longer working is my plummeting sense of self-worth. So much of our identity is wrapped up in work, especially when coming from an all-consuming career like academia. I loved what I did. I was happy working all the time, including evenings, weekends, and even holidays. This was my natural tendency and it was driven, in large part, by my passion for what I did. But now that I am not working, I feel rudderless and am uncertain how to move past the fact that I am not contributing in the way I once did on all fronts, including family.

My major professor from UC Davis once told me, “You have to really want to know the answer to your research question, because your burning desire may be all that sees you through along your path to discovery.” This advice is serving me again. When going through something difficult in life like having a poorly-funded and debilitating chronic illness, you have to really want what’s on the other side to make it through. My desire to understand this illness and get better takes me to some difficult places. The reward of knowledge, and hopefully better treatments ahead, will help allow me to make it through this transition from the well-bodied to the disabled.

When I was a professor, I taught a professional development course to my undergraduates in which I emphasized the idea of transferable skills. I always told them, “People change, plans change, but your skills travel with you.” Well, my plans were changed for me and I am now having to draw on some of my own experience to discover what my transferable skills are and how I might be able to apply them in the fight to bring awareness about ME/CFS, and with that, hopefully vastly increased research funding from NIH, private funders, and other sources.

I love to help and support people. I love science. I love writing. Somehow, I will combine these skills and find my new life’s calling. I trust that next big idea will come to me, but that is not what this phase of my life is about. I can no longer pretend that I can contribute to society in a consistent and meaningful way while I am this ill. Now is the time to make room for my sick self. I will pick up the pieces when the time is right, and when I do, I can well imagine that I will be a different person. I welcome that day.

I don’t want to define myself by my condition, and luckily have ways of ensuring that this does not happen to me completely. Having a young son is a great way to remain tethered to the healthy world. Yet I, along with 20 million other souls on this planet with this disease, am fighting for my life. Not only are we fighting for more research funding, but we are fighting back the stigma that has prevented breakthroughs on this disease in the first place. For evidence-based medicine to truly work, we need evidence. Evidence requires research dollars. To get research dollars we need increased awareness. I think an effective way to raise awareness is to help people understand that this horrific disease can happen to anyone. So, for now, I am making a deep dive into the world of all things ME/CFS – research, support, and activism.

My dream one day is to walk into a doctor’s office or the emergency room and have them understand right away what kind of care is needed, as occurs with other major illnesses affecting millions of people worldwide. In the meantime, I will apply what energy I have to recovering and helping make this dream become a reality.

- Have a story you’d like to tell? Health Rising is looking for stories like Amber’s on how to cope with the issues (lost careers, relationship issues, financial issues) that often come with having a chronic illness. If you’d like to share your story please contact Health Rising via its contact form.

- Health Rising’s “Lives Interrupted” project will soon give people with ME/CFS an opportunity to demonstrate the costs to career and finances this disease so often imposes.

Caroline,

Your story of loosing a career to chronic illness resonates deeply with me. Thank you for sharing.

This is the most comprehensive description of my life since becoming ill with ME/CFS. The loss is overwhelming. Thank you for putting into words the feelings that have griped me for 10 years.

Same here. You are not alone. Many others are experiencing the same thing in their own worlds made small by their inability to get out or to participate in things (due to sheer exhaustion, not lack of willpower or interest as outsiders may think).

Thank you for this beautifully written piece. As a parent of a young woman who never had the chance to get a career as she was diagnosed in her teens, my heart goes out to you. Finally ME/CFS is starting to ge the attention it deserves. Thanks to women ( and men) like you , we need to ensure this momentum continues.

Caroline, you write beautifully on a subject so important to so many of us! Your idea of keeping going will keep you going and your advice and story will, I am certain, stay with so many who need it. Thank you and may you have even more courage.

Thank you Caroline for such a poignant and beautifully written article which describes so well the causes, frustrations and limitations involved in losing your former life to ME. You also offer hope and courage to all of us to make the most of what we do have and to live the best life possible.

Oh, Caroline…You are such a beautiful writer, and have spoken what many of us cannot. Thank You! I have been home bound/bed bound for much of the last 32 years.

Keep Swimming Upstream…and Keep Writing!

I salute you for your courage and persistence Pattie after being ill for so many years.

I can relate so well to your very apt description of the effects and frustrations of ME/CFS. It was never my intent to retire from work (not to mention all the other activities I have learned to do without). I miss the connection, not only to people, but to feeling like a functional, useful human being. It’s not an easy path to be on, and one with little support and understanding.

I agree that so much more is needed. Not only research and the financial support required to make it happen, but in bringing about better visibility, understanding and education. Unfortunately, they tend to be wrapped up in each other. Waiting for that sudden breakthrough discovery that makes ME/CFS (and us) acceptable is not an affordable luxury.

I wish you all the best to making your dream a reality.

I think the loss of feeling of productivity, of using the skills the skills many of us learned, is one of the hardest things to handle. I’m able to be fairly productive but it’s nothing compared to what I feel I could be doing if I was healthier.

Besides the personal losses, think of the losses to society causing by so many people languishing in poor health. It’s just astounding.

Yep. I hear you! I contracted EBV when I was 29 and now survive on a Disability pension. As well as missing my career, I really miss playing sport. Surfing was my greatest joy, and now it is painful to watch others do it while I sit and watch from the sidelines. CFS destroys relationships,careers,fun, spontaneity, & dreams. What else can I say? It is not the life I planned or want. It is not a “life” at all. It is an existence to be endured.

That’s a tough time to get EBV…..Our bodies can easily fight that bug off when we are young but as we get older they have a really difficult time doing that. I wonder how many people with ME/CFS simply contracted an EBV infection too late….

I did. I believe contracting EBV later in life is a big cause of ongoing cfs/me. I was 29 and the doctors said it was the worst case they’d ever seen. I am now 51.

I can personally feel your pain. I contracted EBV when I was 35 and it has stolen my life. I am 77 years old now and close to the end of my life. Its been a very lonely life because most of the 40 years no one had a clue what I was suffering from. I’ve missed out on my children’s lives, and now my grandchildren’s lives. It’s not life it’s an existence that I wouldn’t wish on the ? devil.

Thank you so much for sharing your story Caroline. Your thoughts, I am sure, echo those of so many of us who have ‘lost’ our careers. After 22 years I still struggle with the idea that I most probably will never work again.

I, like you, fought to keep going, and I now believe that was my undoing. I am desperate for worldwide education for general doctors so that they can advise M.E. patients to rest in the early phases of the disease. I do wonder how different my life might have been.

However, I cannot put all the responsibility for my decisions at the doctors door. Society expects us to ‘fight’ illness and I was always ‘proud’ of my ability to work through several serious medical conditions prior to developing M.E. I do feel my pride played a role in this too.

I do hope that now you are resting and pacing that you will find some improvement, even if it’s only small to begin with. I am sure you will find several online communities that support those of us with M.E. and many offer extremely good advise. Most importantly I feel they offer genuine acceptance and appreciation of our day to day struggles. It’s great to feel you are not alone in this.

I too hope that one day there will be a general understanding of this disease. Thank goodness for wonderful sites like this that raise awareness.

I think you’ve hit on a key point Caroline. Yes, the doctors point us in the wrong direction but too often we so want to have our normal lives back, we so want not to be burdens, we so want to fulfill our ideas of who and what we should be – that we push ourselves ruthlessly – too often end up being unwitting participants in our destruction. These are really strong drives to battle. (Of course there are economic considerations as well!)

We could probably us some kind of emotional training that would allow us to stop pushing so hard – to kind of at least temporarily let go – earlier in our illness instead of driving ourselves to collapse.

For me, I know that my “driven-ness” definitely survived ME/CFS! Julie Rehmeyer described a remarkable moment when that ever present drive to succeed just dropped away from her.

That was quite a transformation….

Oh my god, what an amazing comment Cort! This resonated with me so intensely. It took me years to get out of abusive relationships and environments that perpetuated and worsened my cfs. Only to realize, I had to stop abusing myself first!!

Improving from cfs has everything to do with awakening from the performance and worthlessness paradigm deeply rooted in our culture. The good news is, on this track we are only closer to the spiritual enlightenment, the bad news is, it’s painful!

Over the years (17), I have found total peace with myself sometimes, but otherwise I struggle all day everyday because all my thoughts are about work. Why am I not working? Should I be able, as others say? Am I faking? I should be able to find some work I can do. I am lazy. When will I work? What would be a good career in my condition? How can I make money to fulfill my dreams? why am I an imposter? Why am I so useless? And on and on… See the drill?

I have been bedbound 7 years, and ill 17 years. I have never had a chance to start a career cause I was young when I became ill, never defined my identity. I feel like a huge failure. I was travelling around the world backpacking, hiking, and an artist. All of this have vanished.

I don’t even have ideas in my head, I struggle to make oatmeal! (Lol) Now Im old and I have not lived my life. Thanks so much for this post, it’s such a relief to know Im not alone…

You re not even close to being alone. Doesn’t our mind go crazy? All these thoughts about what we should be doing? What’s wrong with us? Blah, blah, blah, blah…..It just torments us again and again and again. It cares not that there is a physical impediment to doing those things. Isn’t that weird? That is so weird….

The really weird thing is that even healthy people have these kinds of thoughts – just in different form. Am I doing enough? I’m lazy. When is my real life going to start? I shouldn’t be trapped in this relationship. My job isn’t fulfilling. I spent my life working….

It’s the same thing – in different form.

My heart cries for you as it cries for all of us. The careers, the marriages, the relationships…gone. As long as we are alive there is hope. All we can do is the best we can do with every moment we have. Thank you for sharing.

I, too, lost the career of my dreams 26 years ago. Raising my two children was always an acceptable reason for my not working. Once my children went off to college, it got harder to justify to others. I did not share my medical condition with most people. I volunteer now working with stroke victims. I feel useful and fortunate compared to their inability to talk/read, etc. Also, when I am not well enough to go, I don’t carry the guilt I would if I were getting paid.

I too lost a career, marriage and many friends to illness. Your writing resonates with many, especially me.

Thank you.

Caroline, it was cathartic for me to read this. I’m 63 but my career path was very similar to yours, including getting mono after age 30. I pray that more research gets funded, very soon, that leads to effective treatment. And you can resume a productive life.

Caroline,

I also undergo the same sentiments due to my own me and fibro. I used to associate my value with the degree of work I was able to churn out but now have discovered a new sense of self and along the way have become more compassionate towards others and realized how important it is to take care of myself amongst many other lessons learned. Know that you are not alone.

Thanks Caroline. I think a compassion for ourselves is very important. It’s amazing how hard we are on ourselves! Harder than others would be on us.

So hard, sometimes, to just give ourselves a break…

Caroline, thank you for sharing so eloquently your long struggle with ME and the insights you have gained. I understand and am very sorry about your suffering. I have had a very similar journey, wonderful professional life, rich personal life and then suddenly so sick I couldn’t accept it. After four years of trying hard to maintain my various academic jobs and not succeeding, I had an exceptionally serious relapse and have been fully disabled for 14 years. Such loss and grief overwhelmed me during the first decade. Now I try to find and crystallize moments of joy each day so I stay above my disease and am not defined by it. Sometimes I cannot stay above the pain and loss and look forward to the end of my life, but most days I don’t feel that degree of suffering.

I respect you highly for sharing your story so well and send you my comfort and solace.

‘My dream one day is to walk into a doctor’s office or the emergency room and have them understand right away what kind of care is needed’ – Your dream is mine. Thank you for sharing your story so eloquently. I had Glandular Fever aged 16 and my mum said I was never the same after that. I got a degree and a PGCE but following Shingles I had to give up working 5 years later and I could have written what you wrote myself.

Again, exposure to EBV as an adolescent or older person is just so much harder for the body to overcome. Something apparently happens during the fight to get rid of the virus to cause ME/CFS. My guess is the more serious an infection – the harder it hits you – and the more difficult it is to fight off – the better chance there is of something going wrong and staying wrong.

A really nice start for the medical profession would be to chart the outcomes of adolescents and adults with mononucleosis more closely.

Thank you. Everything you have written resonates deeply with me too. ME is the ultimate thief. 35 years has taught me some things can improve, not least the acceptance of limitations but also recognising the opportunities, different yes, but still opportunities. It puts us all on an unlooked for path, hopefully one where we can find the understanding and increase in consciousness we could find nowhere else.

I appreciate all the effort you put into writing about your life. I am always sorry to read about yet another life devastated by this illness.

I highly recommend Toni Bernhard’s book, How to Be Sick. I have found using her easy to understand Buddhist take on this illness a saving grace.

All my best to you.

Bobbie

Dear Caroline, You have expressed so well what happens to so many of us.

The loss of a career in my case Palliative care Nursing was extremely painful and grief filled. Allow yourself to grieve your loss. I have had ME for over 40 years now and with much help from a wonderful ME/CFS specialist here in Melbourne Australia I have improved somewhat and am now able to do with pacing much more in my life. Doors closed over the years but I have found that windows have opened too. Your skills will I am sure prove to be most useful to you in many ways, perhaps in ways you would never have imagined. There are many online Groups that you may consider joining to ease the pain of being alone in a new town without contacts. Good luck

Dear Caroline,

Thankyou for this generous, searching, heartbreaking essay which resonates so deeply with my own story too, in common with others here and elsewhere I’m sure.

I was a curious explorer of the sacred wonders of this world for some thirty-three years – though the territory I purvued as a therapist belonged to the inner landscapes of individuals’ interior world’s – until a bout of Whooping Cough in December 2010 finally and prematurely ended a journey that was beginning to bear fruit after long toil. I was 56, a mono survivor since age 20, for whom weekends and holidays recuperating in bed had simply become an unquestioned fact of life, the price paid for the privilege of doing the work I loved.

The unchosen path since the WC felled me has been harrowing and deeply intriguing in its own way. While I was relatively lucky to find a wonderful doctor in Australia who gave me a medical name for my condition along with sympathetic, sound advice that meant I was spared the ceaseless searching and the awful self-doubt many less-fortunate patients are made to endure, I rather wish a diagnosis might have hijacked my career path decades earlier when there was so much time ahead in which to learn and subsequently implement new wisdom… It’s not to be, and yet this illness delivers gifts even as it takes away so much.

I hope your story is widely read, Caroline. It gives a measured yet evocative account of your lived-experience grappling with the mystery, devastation and revelation that is ME. I can imagine the price you paid in terms of the PEM, a fact which redoubles my gratitude.

Wishing you ongoing courage and hope, and ultimately, the gifts of health and renewal Xx

Dear Caroline, along with the above commentators I want to thank you for your moving story of the losses that come with our disease. At the same time, your evocative account of your experience of the Kogelberg Biosphere Preserve has given me some insight into a place I will probably never see for myself. So thank you for that as well. We need to have some poetry in our lives. Best wishes for your future.

Such a moving account of your health journey, but I can assure you, you are not alone.

I might suggest your education and skill in writing might be the answer to your question on what you can do next.

Write…….but pace yourself.

Listen to your body and learn to read its subtle signs that its struggling and needs to shut down for a while. I’m sure you’re probably well-experienced in doing that anyway after all this time.

Anyone with ME/CFS/FM learns that there is no easy fix and while one shouldn’t give up on improvement or even getting well, one should accept that it might be a long haul before anything noticeably improves. Good healthy fresh food and a simple life helps enormously. I go to bed late and get up late. If my sleep has been disrupted due to pain or heart symptoms (I have an inherited heart condition), I stay in bed until I feel rested enough to get up.

I often have a sleep for a couple of hours in the afternoon as well.

Lack of deep restorative restful sleep is something that even healthy people lack these days. It’s vital for your organs to rest and replenish their reserves. Hydrate with plenty of fresh water, filtered if possible.

I’ve read many stories of a return to health, but often the person returns to a different life and reduced activity level. A return to good health usually means a different reality (to the life they led before they got ill).

Live your life in Mindful awareness of each task – mental & physical. Thich Nhat Hanh’s book on the Miracle of Mindfulness has taught me to stop thinking about the past, or planning for the future. It’s taught me how to live in this very moment and enjoy what is (rather than what was, OR worry about tomorrow).

Don’t forget your spiritual health (either) – its important. The Mind is one of the most powerful tools and learning to find Joy in the simple things is paramount.

If you haven’t already done so, I might suggest you read the book How to Live Well with Chronic Pain and Illness – A Mindful Guide by Toni Bernhard. ISBN 978-1-61429-248-7 (as should others with Invisible Chronic Illness).

This book is the book I would have written if I had the skill and energy to do so. It speaks from the heart and a wealth of experience. Its easy to read. It’s informative and at times, downright funny. It makes sense out of Chronic Illness. This book, together with much reading on Buddhist Philosophy over the last 25 years or so, has kept me sane, (even if sometimes I feel down and empty). I’ve finally accepted that its ok to watch daytime TV, although my many nature and travel DVDs play a big part in my life too.

And my Photography hobby has worked wonders……. although my severe back pain and deteriorating eyesight is reducing that somewhat these days. When I took up Photography after having to give up full-time work and apply for a Government Disability Pension nearly 8 years ago, I finally found something that didn’t tax me too much.

I live my life in slow motion. I’ve trained myself to move slowly, to think slowly and to appreciate what I have (instead of what I haven’t).

Interestingly enough, I did one of those brainetics (?) tests on the internet a year or so ago and discovered that my memory was 35% better than most people my age and my ability to problem solve was something like 65% better.

But the speed with which my brain worked was 35% slower.

Interesting, because my short-term memory is poor (in my opinion) and my cognitive dysfunction is intermittent. The fact that my brain works slower might simply be because I’ve trained it to do so (so my energy envelope is neither drained or disrupted with unnecessary tasks).

Yes, studies suggest that given enough time people with ME/CFS are as smart as ever – they just can’t process information as quickly.

What a GREAT practice – living your life in the now…rather than comparing our lives to the way they were in the past or to how we think it should be now. Great advice for anyone – healthy or ill.

I have enjoyed reading this fantastically written article several times since written & all the comments are great as well! I haven’t been able to continue in my career for almost 11 years now. There is such a loss of everything mentioned & I cannot think of a thing to add. I would encourage all of you out there to write of experiences & hopefully someone could pull this all together in a book as encouragement to others as we can help each other. I do have a whole regimen of supplements that I have researched & am taking. I may be bedfast without them. One thing that some mentioned is all the other deteriorating physical symptoms & diseases that have piggybacked the illness. I finally was told RA but there was no family history. My osteoarthritis is severe & my medical doctor admitted that I was most advanced & started earlier than any one he has seen.

The previous comment was very interesting as far as mental activity & brain function as I go through bouts of not being able to take care of business & make coherent decisions. I consume way too much caffeine & was previously on 6 Ritalin a day. More than just brain fog which we all know intimately.

My prayers to all as I reread this exceptional article & the gracious comments.

Thank you for sharing. Your words echoed so closely the path my life has taken these past 6 years. You write with truth but also passion and I hope unfalteringly that your vision for much needed research to lead to treatment comes to pass before too long.

awful but all too familiar story, yet somehow you managed to make this an ‘enjoyable’ read! and what a shame of what must be the most awesome career one could have ;( since a neurologist can’t back it up (but they’re terrible at listening grrr) it’s mostly guess work but EBV and some others got into my nerves, got them out somehow but restoring metabolism is quite a, er, challenge

This mirrors my feelings and some of my experience (though I have tested positive for Lyme more than once including spinal tap, I have also tested positive for Epstein-Barr multiple times over the years since 2009, including “chronic Epstein-Barr”, which as you say in the article, isn’t believed in.)

Thank you for writing this, I understand the effort it took, both physically and emotionally. I will be sharing your article widely.

You took me back to see the Namaqualand daisies rising out of the red earth after rain. Your writing evoked such treasured memories before getting sick in South Africa a quarter of a century ago.

Powerful writing. You told my story too. I was lucky to be able to drive to a little town in the Karoo that had a hospital and a caring doctor. I had a viral encephalitis. I got excellent care from the doctor who could speak English, but booked myself out after a week because I “had” to get back to work. Just landed up in more hospitals. I should have rested. I pushed and crashed and am still doing it, but mostly bed now. ME is a sod and as persistent as a Namaqualand daisy; pushes it head up although you think it is dead and gone and will never come back. It does. Year after year after year.

Hi,

Welcome to your new community. Instead of sharing my struggles or condolences, I would like to share some ideas to try.

1) do a UBIOME explorer test and examine you microbiome.

2) Find a doctor to prescribe LDN, famvir (start slowly) on both

3) Add liposomal glutathione slowly

4) Try other anti-viral supplements (olive leaf) along with a variety of probiotics (see cfsremission.com)

5) Look into IV ozone

6) Look into FMT

7) Keep looking and learning

your last name means mono over here

that’s it ;o)

Wow what a spot on piece. You captured so much of personal experience with all kinds of loss, including a cherished career. And you also added in so much good science, that I will use this to educate family, friends, and former co-workers (as well as disability insurance who is denying my illness). Thank you and best of luck to you.

Thank you deeply for your courage to share your story. It helps the rest of us to feel less alone–and hopefully you, too. For all of us I sense an undercurrent, a belief that our story must matter, that being knocked out of the working world must elicit a response from our society as a whole that this loss is unacceptable, that HELP WILL BE ON THE WAY. Thank you for sending out this signal flare.

“Within moments I had an answer: at the ripe age of 32, I had mononucleosis. Before leaving the exam room, the doctor told me that, “Sometimes people don’t recover from mono, especially if the onset is later in life. And you may be more likely to develop lymphoma, so keep an eye on that.” Who ever heard of mono not going away and causing cancer? I found that to be rather alarming but promptly put it out of my mind.”

—————————————————————

Tahoe World Oct 24 1985

Incline Doctors Disagree On Validity Of The “Tahoe Malady” Diagnosis

By Jean Lamming

Recent claims of an outbreak of chronic mononucleosis in the North Shore area have created a rift in the medical community with several doctors saying they have seen no evidence of the phenomenon in their practices.

Dr Elliot Schmerler of Incline Village said he spoke with several doctors who have seen few if any cases of the fatigue associated with mononucleosis in their North Shore and Truckee practices. “The rest of the medical community differs with what has been going on,” he said last week.

Over the weeks the 90 cases of chronic mononucleosis diagnosed by Incline doctors Paul Cheney and Daniel Peterson have gained national attention. Investigators from the Center for Disease Control spent nearly three weeks in Incline in late September studying the evidence of the outbreak, which doctors say appears to have run its course.

However, several doctors have criticized the diagnosis and the use of a new test whcih is key to the medical conclusion.

Schmerler, as well as Incline doctors Harry Weigel, Barry Levenson and Gerald Cochran say neither they nor any other doctors who practice on the North Shore and in Truckee have evidence of an outbreak of fatigue in the past 10 months.

“I think it’s very unusual for all the cases to show up in one physicians office in a small community and because of that I would question the reliability of their testing,” said Schmerler. “There has to be something wrong with the diagnosing procedure.”

In the face of the dissent, Cheney sticks by the diagnosis and the new test he and Peterson used. He admits chronic mono is little understood, but said the conclusions were drawn on patients symptoms and solid blood tests.

“The thing is that most important is the diagnosis we’ve made meets published criteria. The diagnosis of mono has always been a dilemma, though physicians by the thousands make this diagnosis each year using tests far less accurate than that used in this study.”

The Center for Disease Control (CDC) which doctors generally hold in high regard refuses to pass judgment on the test, or diagnose the cases studied, until laboratory tests on patients samples gathered in Incline are complete.”

“There is no question that there are some people in the area that are ill,” said Jon Kaplan, a medical epidemiologist from the viral disease division of the CDC. “We think that doctors Peterson and Cheney do a good job. We’re just trying to help them come to some definite conclusion about this.”

Cheney and Peterson say the 90 cases they diagnosed as having chronic mono came from a group of 150 people spread around the North Shore and in Truckee who complained of fatigue. The cases began to trickle in January and peaked in May. They were clustered in two schools, one casino and a basketball team, say the doctors.

Peterson and Cheney said the 90 cases could represent the first documented case of a chronic mono outbreak.

Peterson said at a press conference that 10 of the 150 patients tested for the illness have not recovered from the chronic fatigue for months, and may have suffered permanent damage to their immune systems.

At the heart of the controversy is a new test. Epstein-Barr virus antigen panel, which measures the antibody level in the blood. Cheney and Peterson are the only area doctors found to date to use the test in a great degree.

Each of the polarized factions can present medical findings supporting and questioning the use for and interpretation of the new test. The Cheney-Peterson tests were performed by the Nichols Institute in Los Angeles at a cost of some $70 to the patient.

Kaplan admits the test has not been widely used before and results of it are part of their evaluation. “Some of these tests came back positive and we’re trying to see what that means.”

Meanwhile, opposing doctors say the chronic mono claims have caused undue concern among residents and tourists are staying away.

“It’s had a big impact,” said Schmerler. “We are just getting bombarded with people calling. Before it gets out of control, I’d like it stopped.”

According to Weigel, “I know as a fact people have cancelled their reservations and people have left early because of the newspaper articles about the epidemic. I think that is terrible and completely unnecessary.

Cheney reinforced previous statements that the illness is waning. He said he hasn’t seen any definite new cases as of late summer, and believes the illness had its roots in a virus that spread in winter and early spring and activated the chronic mono that is latent in most adults.

“It has a beginning, a middle and an end. It’s not a mystery illness in that we don’t know what it is and it’s not a threat. It is very difficult to transmit,” said Cheney.

Local doctors also questioned what other findings and proceedures generating from Cheney and Peterson.

Levenson and Schmerler said because fatigue is such a general symptom, it could spell many situations besides chronic mono. “Fatigue is one of the cardinal symptoms a doctor sees in his practice,” said Levenson.

Schmerler addid, “There are a lot of reasons for fatigue and depression is one of them, Once you start publicizing the fact that you have a group of people that are tired youre going to have a hysterical reaction in the community.

Levenson also recommended that anyone who has suffered fatigue for many months should see an infectious disease specialist.

Cheney’s reaction to the mobilization against his diagnosis was disappointment. “It’s really unfortunate that the physicians have to battle this out in the newspaper.

Many patients consult many physicians and get different opinions. I think that is at the root of all this. You can have competent physicians analyzing the same data and coming to different conclusions.”

Teaching was my passion, my life too. At best I can do a small fraction of small group/ individual work, for that I am very grateful. Periods of ‘ managed’ health are followed by periods of pain, mobility problems and unreliability. The guilty suffices with each relapse, wanting to teach,but unable to. I have an 8 year old son and 11 year old daughter,for whom I need to be ,’ mum.’ The role is fluid and there may be things be cannot always do or would like to do, but the most important thing is they know they are loved and for that there are no relapses!!!

Beautifully said Katrina.

A very moving account that took me back to the loss of my career. I became ill in 1964, aged 14, with what was later diagnosed as ME, so lost my chance at tertiary education and a normal life.

After several unsuccessful attempts to work I turned a hobby, designing and making jewellery, into part time self employment, which I loved. The illness has gradually worsened since my late 30s so my work output declined to almost nothing. It was very hard to admit defeat and stop entirely 13 years ago.

Afterwards I did a bit of slow sedentary gardening for a few years, which may have worsened the illness but resulted in some lovely crops of fruit each year.

Now I research family history online which keeps me in touch with relatives, gives a sense of achievement and best of all can be done on the laptop in bed.

Glad you found a way to contribute Elena 🙂

Your story sounds so much like mine… God bless you!

I cannot add anything substantial new to what has already been written by Carolyn Christian and all the others who have commented. I am one of you. I’ve been sick for 30 1/2 years with ME/CFS. I was diagnosed with chronic EBV, CMV, HHV6 & others when I was 48 yrs. old, in the middle of an enjoyable and highly treasured career, as well as a new marriage. I have lived in an assisted/independent living facility with my husband for almost 10 years. My body is failing me badly now, and I don’t know how much longer I can survive. I’m a fighter, curiosity drives me to continue learning and serving. I’ve lost all connection with almost all friends, and my grandchildren have never known the real me. My children cannot depend on me for anything. I’m virtually apartment/bound and often FOMB (flat on my back) for days. I live on Nauzene, Rice cereal, peanut butter, yogurt, honey and crackers. That’s all my body will barely tolerate. My BMI is dropping alarmingly. But I still love life, enjoy music, art, literature, jokes in my good minutes. That’s how we live; One minute at a time. Not days, minutes. Thank you for that brilliant article, Carolyn. May a cure be discovered soon for all of you younger people. I am reconciled to the fact that it won’t come for me. I am not depressed, I am just very sick! I am thankful for the internet which allows me access to articles like this one, and connections with others who are my “friends” even though we will never meet. Keep fighting, don’t give up. Things have to change.

One minute at a time…. Thank you for the reminder Sheila.

Hi Caroline: I got mono/glandular fever in May 1994 just as I started a faculty position at Auburn University and, as you can imagine, I did not take any time to rest during that important phase of an academic career. Your story, including the year of Lyme treatment, parallels mine closely. I moved to a small teaching college in the hope of a lighter work load, but even that was not enough. I am now on partial disability, but I am still able to teach a few classes a year and do a little research, for which I am grateful. I have moderate ME/CFS with dysautonomia (including non-POTS orthostatic intolerance) and chronic migraine. I am bed-bound 1-3 days per week and the other days I am in bed from about 2 pm onwards. Despite all treatments I have tried over the years the trajectory has continued to be downward. Apart from the frustration of the “you don’t look ill” issue, the most frustrating thing has been trying to serve as my own physician due to the inability to find any doctor able to investigate and coordinate treatment of a multiple system illness like ME/CFS. I am currently seeing an open-minded migraine neurologist and who is the best I have been able to find, but he has no experience with ME/CFS. My thoughts are with you and all the other people suffering alone with this disease.

“The most frustrating thing has been trying to serve as my own physician”…..this! I share in your frustrations, Mark. All the best to you. Hang in there!

Thanks for sharing your relatable story, Caroline.

Yes, trying to be your own physician (and researcher on the web)

requires so much time and energy—but it’s a continual avenue of hope.

What an eloquent expression of your loss–the world’s loss of your prior career contributions–Caroline. And compelling descriptions of the desperation with which we all grasp for improvements in quality of life, e.g., “I use a heart rate monitor like a shock collar….”

This cogent summation of our situation is probably the best I’ve seen: “We lack a good diagnostic test because funding from NIH has been woefully inadequate, probably owing to the damaging views about this illness peddled by psychiatry. Why do most major illnesses have such a dark history of blaming the patients? How can we be living in the 21st century, with the technology we possess at our finger tips, and still not understand a disease that is more than four times as prevalent as multiple sclerosis (MS) and that carries a quality of life on par with late-stage AIDS and congestive heart failure (CHF)?”

I hope you are able to keep writing, keep questioning. It is a service to all of us who have lost our identities and abilities. Thank you so much for using your energy and talents to weigh in on this forum.

Thank you – all of you – for your incredibly kind, supportive, and inspirational words. I really appreciated hearing how many of you here have found grace and belonging within this illness. Your comments have shown me that joy and meaning can be found even within the smaller confines of life with ME/CFS. The wisdom you have passed along here serves us all. In gratitude – Caroline Christian

Hi Caroline,

One thing that I have found that helps me is listening to books on tape. There are many books where you can learn about different ways at looking at medicine and at problems as well as many books to just keep you entertained. It makes me feel like I keep learning and helps to distract from how weak I am. I have a chair in my backyard among the trees that I lay in (It is positioned so my head is slightly lower than my legs which helps with the ANS issues.) Sadly, I am in Miami so this is the one time of the year when it is not too hot to enjoy being out there. Let me know if you want any suggestions on books to start with.

Thank You Caroline, your story is very similar to mine, especially your reference to “post exertion malaise “, which forced me to abandon my construction business at age 45. I still cling on to some casual light building work but it’s really only a recurring cycle of beating myself up followed by days or weeks of complete rest.

I know at some time a cause and cure will be found.

As many as 50% of patients Diagnosed with CFS Fibro IBS are misdiagnosed according to a Harvard Neurology Professor at Mass General Hospital who said they have instead (aaSFPN) ‘apparent

autoimmune Small Fiber Polyneuropathy’ on Skin biopsies testing…There also has been a lot of speculation over the years that EBV HHV6 CMV Lyme etc. are a Cause which has never been proven…I

have also seen in EDS Small Fiber Polyneuropathy as well…50% of People are a lot of patients which would mean 1 out of 2 never had ME/CFS Labels, to begin with…Once this diagnosis is

confirmed there is a long list of elimination process to be carried out & one is Hep C aside from many on the list…Imagine all the people all this time completely misdiagnosed even on the

list of elimination is also toxicity from Antibiotics…Even the so called Recovery Stories are questionable if 50% are actually misdiagnosed

Thank you for sharing your story. It resonated very much with me as I face the prospect of having to give up a professional career I have somehow managed to cling to since first getting sick in 1996 after a bout with EBV. I have had two remissions and relapses since then, and with each relapse the disease seems to sink its claws even deeper into me. I am feeling scared and defeated today, but it is comforting to know that I am not alone.

Caroline, thank you for sharing your story. I feel the same as far as loosing a job I loved, the isolation can be unbearable at times. I’ve always been a very social person, love interacting with people and started working when I was 11 years old. My sister and I both did housecleaning, babysitting, ironing etc to make spending money. I never thought I would end up on SSDI. I had no idea that fibromyalgia was going to be so devastating. The financial strain is huge. The people who I thought cared disappeared. Even my immediate family were more critical than helpful. Now in my early 60’s I’m facing a scary future. My husband is an alcoholic. This entire year has been a nightmare so the only option is getting a divorce. I am loosing my home and have no idea where I will be living or how I’m going to afford living on my own. I have made progress with FMS in the pass two years, however the constant “waiting for the next shoe to drop” has caused too many setbacks.

I also wanted to point out that I live in the Central Valley so escaping the heat sure hit home.

Thank you again

Dear Marsha – Thank you so for your kind words and for sharing your story with me. This illness is beyond cruel for everyone, but it is especially hard on those of us who thrive so much on human connection. It is so isolating to watch friends peel away and relationships crumble. The financial strain adds a further burden that only seems to worsen with the passage of time. If we could be sick for 5 or even 10 years that would be one thing, but as more time passes the losses really start to accrue. I am here if you ever need a friend to talk with – you can find my contact info on Sonoma State’s website. I’m thinking of you, sending very best thoughts, especially during this holiday season, when so many of us struggle. – Caroline

Please take a look at http://meatheals.com/, switching to a diet of fatty ribeye has been life changing for me. I hope you can enjoy the same health recovery. What have you got to lose?

Oh Gosh this one rang true to me. I have suffered from a chronic spinal fluid leak that left me bedridden after the birth of my 3rd child. I was bedridden for 3 1/2 years and none of the treatments lasted. I lost my career as a clinical psychologist, a mother, a wife and a member of society. I learned time passes and goes on. The loses with chronic illness are so hard and the grief runs deep. The active, happy, physical fit, working mom of 3 became a shaddow of a human life in a bed in tears begging to get help even though I had flown to every major medical institution where even the experts only know little. I often wonder if now that I am no longer leaking if CFS is my issues. Profound debilitation fatigue that leaves me in bed for days despite all my will power and instinct to mother can not win. I pray that rare illness can get more attention and funding. Thank you I believe our stories have power to make change.

Colleen – I am so sorry to hear that you have suffered from chronic spinal leaks. It must be so frustrating when the treatments don’t work – the perpetual hope/grief cycle. I have been working with Dr. Ian Carroll to see if I am a leaker but we are taking is slowly as there are so many other medical issues to tend to. I have profound empathy for leakers and know how debilitating the condition is. Have you looked into Dr. Carroll at Stanford? It is so frustrating to be on the leading edge of medicine and to not have answers or even viable treatments. I agree – we must tell our stories.

Thanks for sharing, so well done! Your helping so many people by your interactions on social media and your blogs! It feels like you do have your new job and it’s heart centered, informative, researched, lived, valued, loving, and your giving from a pureness of inner essence! Much love ❤️

Beautifully written, Thank you

Hello Amber, I just wanted to let you know that I have had CFS?ME for 11 years now…also in academia…and this past year I have also had to go on a leave of absence and start exploring disability.

Here is the thing: prior to getting this, I ALWAYS got 7-9 hours of sleep a night. I ALWAYS ate 3 meals a day. I ALWAYS made time to exercise, either swimming or running or hiking. I ALWAYS ate super-healthily. I ALWAYS meditated. Almost daily. SO DO NOT BLAME YOURSELF or your past pushing of things. I do not think that necessarily had anything to do with it.

Sure, it didn’t help. But you might have gotten it anyway. I ALWAYS lived a pretty healthy, well-balanced life. And I still got it.

OK, thanks for your post, best wishes, Anna

Well said, Anna….One would have thought you of all people might have been immune- but no….so many very healthy people have gotten this. Thanks for sharing that.

Thanks for sharing your insights.

It’s so said to hear this and reminds me a bit of my own story.

Nevertheless, I wish you the best for your journey.

P.S.:

If you feel lonely, what about moving to your parents?

Many of us doing this also because of additional cost reduction.

I think your article can inspire many people who suffer from chronic diseases to achieve something great.

I think your article can inspire many people who suffer from chronic diseases to achieve something great. You are doing the right thing this way. I noticed that many people, when they find out that they have some kind of chronic disease, they immediately give up. I understand them because it is more difficult for them to live and even more so to realize their dreams. Still, the strength of spirit and motivation allows a person to forget about their illnesses and move on. When I worked as a pharmacy technician ( https://www.exploremedicalcareers.com/pharmacy-technician/ ), I only once saw such a patient who had been fighting cancer for a long time and did not give up and eventually recovered.