Both depression and inflammation may be present in both chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS) and fibromyalgia (FM). Antidepressants can help some but not others. Evidence that inflammation may cause depression in as many as 40% of depressed patients suggests that anti-inflammatories might be better at mood elevation for some ME/CFS/FM patients than antidepressants.

There’s another reason to look into inflammation, anti-inflammatories and depression, however. Researchers have been taking a pretty deep dive into this subject and in doing so are gaining new insights into how our very complex immune systems function – insights that may be playing out in ME/CFS and FM over time. Be ready for some surprises!

Antidepressants – the New Anti-inflammatories?

Antidepressants weren’t supposed to do this. They were designed to affect neurotransmitter levels in the brain but many studies now suggest that antidepressants can also impact the immune system by reducing inflammation.

The idea that inflammation is responsible or contributes to depression in some people is not new – Michael Maes has been pushing that idea for decades – what’s new is how solid the finding is becoming. A recent meta-analysis of 82 studies (!) implicated a slew of immune factors (IL-6, TNF-α, IL-10, sIL-2r, CCL-2, IL-12, IL-13, IL-18, the IL1ra, sTNF-r2) in depression! Depression, it appears, is at least partly an immune illness…

The depression-cytokine hypothesis experientially makes perfect sense. If the immune system can produce flu-like symptoms which make us crave isolation when we have an infection, it certainly has the potential to make us “blue”.

Anti-inflammatories Instead of Antidepressants For Depression?

If inflammation is making people depressed then it stands to reason that anti-inflammatories might, in some cases, be effective antidepressants. Another metanalysis (of 45 studies) concluded that antidepressant use is, in fact, associated with decreased levels of some powerful, mostly pro-inflammatory cytokines ( IL-6, TNF-α, IL-10, and CCL-2) in people with major depression.

Antidepressants appear to be reducing inflammation in the brain by reducing it in the periphery (the body) first. The key outcome may involve reduced levels of a cytokine (CCL2) which gives immune cells entry into the brain where it’s believed they may cause the neuroinflammation that’s producing depression in some patients.

Raison’s Reasons

The Promise and Limitations of Anti-Inflammatory Agents for the Treatment of Major Depressive Disorder. Charles L. Raison. Curr Topics Behav Neurosci DOI 10.1007/7854_2016_26

Charles Raison has spent his career investigating the link between inflammation and depression. Now that it’s been validated, one would think Raison would jump on the anti-inflammatory bandwagon, but he’s not. Why? Because the situation is complex – more complex than our overworked doctors may have known.

Raison doesn’t completely trust the anti-inflammatory/depression studies for one thing and he tears a number of them apart. (It turns out that it’s very hard to do a bulletproof study.)

Plus, he objects to the idea that there is an anti-inflammatory response or that all anti-inflammatories are the same. Different anti-inflammatories affect different parts of the immune system. Cytokine antagonists attack inflammation early in the inflammatory process while NSAIDs attack it in its later stages. NSAIDs and Omega 3 supplements affect so many different parts of the body that it’s hard to tell specifically what they’re doing.

(NSAIDs, ironically, can actually worsen some cardiovascular diseases by attacking substances that have both pro and anti-inflammatory properties. They may also worsen depression in some instances. Both NSAIDs and omega-3 supplements also have a variety of non-immune effects that could affect depression as well.)

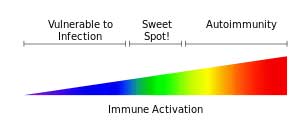

Plus, the situation is simply very complex. Some people are put together in such a way that only the very highest levels of inflammation will trigger depression in them. For others, even normal levels of inflammation can trigger depression. We’ve come across this odd hypersensitivity issue in ME/CFS.

Gordon Broderick has found that in the right context – such as with weirdly ME/CFS-configured immune networks – even normal levels of one cytokine can cause unusual effects. Jarred Younger suspects that even normal leptin levels may be triggering microglial activation and neuroinflammation. Cytokine levels were not elevated in ME/CFS patients in the big Montoya/Mark Davis ME/CFS cytokine study but they still predicted disease severity: cytokines that caused no problems for the healthy controls caused fatigue and pain in ME/CFS patients even when they weren’t elevated.

Only one anti-inflammatory/depression study fits Raison’s standards – his own. His 60 person study of people with treatment-resistant depression compared the effects of the TNF-alpha antagonist infliximab (5 mg/kg) to salt water placebo. That study found that infliximab was not better than placebo at reducing depression, although very high placebo effects may have obscured infliximab’s effectiveness.

A closer look revealed that infliximab did work but only in people with high cytokine levels (hs-CRP plasma concentration = or > 5 mg/L). These people experienced major reductions in emotional symptoms such as mood and anhedonia (inability to experience pleasure), suicidal ideation and psychic anxiety.

Infliximab, on the other hand, actually made people with low cytokine levels worse. Plus, for some reason, high levels of inflammation halted the placebo response in its tracks. Only people with moderate to low levels of inflammation had a high placebo response.

That, of course, suggests that whether or not you experience a placebo effect may depend more on your immune makeup than on your psychology.

Raison’s intriguing findings need to be replicated, but another study employing a different anti-inflammatory – omega-3 fatty acids – had similar findings. On the face of it, omega-3s did no better than placebo in fighting depression, but once inflammation status was taken into account, things changed. People with high levels of inflammation did better on the omega-3s while those with low inflammation levels actually got worse.

Omega-3 fatty acids are often recommended in ME/CFS and FM; if you reacted poorly to them, low levels of inflammation could be the reason.

A major conundrum at this point is why people whose depression is associated with low levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines respond so poorly to anti-inflammatories. Once again, context appears to be key. Animal studies suggest that at lower concentrations, inflammatory cytokines play a pivotal role in learning, memory and neuronal integrity. Dropping those cytokine levels too low could impair some basic processes in the brain.

Animal studies also suggest that animals in a chronically stressed state respond to anti-inflammatories with worsened depression and anxiety-like behaviors. Even more remarkably, inflammatory stimulators (including the notorious lipopolysaccharides (LPS)) actually reversed their depression and did so by stimulating hippocampal microglial proliferation. A small 1990’s study which introduced a toxin (LPS) that ramped up IL-6 and TNF-a levels reduced depression in a set of melancholic depression patients. The higher the increase in IL-6, the better the response.

That’s a fascinating finding given the Lipkin/Hornig study results suggesting that long-duration ME/CFS patients have low levels of inflammatory cytokines. Could it be that some of these patients could benefit from a little more inflammation?

Conclusions

Thus far, it appears that people with depression and high levels of inflammation can benefit from anti-inflammatories. (Raison notes that high hs-CRP levels are easily attainable). People with depression with lower levels of inflammation may actually get worse on anti-inflammatories.

More importantly, Raison’s review shows how complex the immune system is – a fact that’s been highlighted more and more in ME/CFS as the results pile up. The idea – unproven, but a possibility – that a pathogenic toxin could be helpful in depressed people with low inflammation levels is nothing if not startling. So is the possibility that one’s ability to get benefit from the placebo response – and therefore presumably from mind/body treatments – could be determined by the amount of inflammation present.

Gregory’s story demonstrates how many twists and turns the immune system can give us. Gregory, who was severely ill, had tried just about everything until he hit on Celebrex, an anti-inflammatory. To his surprise Gregory went from being able to only walk short distances to a near normal life. Gregory’s energy kick and mood elevation lasted about six months and then disappeared.

The question of how to properly rebalance the immune systems in ME/CFS has come up before. Dr. Klimas, a clinical immunologist, has noted that either immune activation or suppression is called for in different patients (and woe to the patient who gets the wrong treatment). Dr. Klimas’s statement, that we know people recover but we’re not sure why, highlights the fact that underlying factors we don’t know about are affecting treatment outcomes. Dr. Klimas and Gordon Broderick’s intensive analysis and modeling during exercise in ME/CFS suggests to them that they may have uncovered some of those hidden immune factors.

Rituximab will be a good case study in this regard as it clearly works for some people with ME/CFS. Now that the Rituximab trial failed to meet its major endpoint, Fluge and Mella’s challenge is to identify what immune factors make a difference in ME/CFS. If they can identify those factors, one piece of the immune puzzle that is MECFS will become clearer.

The bad news is that the immune system is more complex than imagined. The good news is that researchers realize that and are beginning to look for it.

Depression can also be caused by imbalanced methylation, zinc and copper imbalance, or histamine excess, all of which can be issues in ME/CFS patients.

In regard to immune suppression or activation, many patients have both underactive and overactive immune systems, or as my top ME/CFS specialist calls it, a dysfunctional immune system, making treatment more challenging – it can be a bad idea to suppress or activate the immune system in these patients.

Its complex and we are a long way from solid answers. Just hope the researchers can keep going to find a more comprehensive view with a roadmap to meaningful treatment.

I think that Dr. Klimas, a clinical immunologist, has said the same – both over and under active immune systems can be seen in the same patient – making treatment options difficult to choose.

With the Rituximab findings, the Mark Davis T-cell studies, the Unutmaz immune studies and quite a few others we’re going to be learning quite a bit about the immune systems of ME/cFS patients over the next year or so.

Cort, how were you able to see Dr. Klimas? Does she have a private practice? Do you know if she will see patients remotely? I can’t find contact info for her anywhere.

Can I ask who your ME/CFS specialist is?

I just started seeing Dr. Klimas – my first ME/CFS specialist in over 15 years 🙂

How do these studies identify high or low inflammation levels? Entirely based on cytokine levels?

I know several used hsCRP levels. I don’t think they’re using cytokines actually.

Columbia study concluded that the cytokine levels do not explain the symptom severity. It could be the hyper-sensitivity to inflammation rather than the inflammation itself. That could explain why anti-inflammation drugs are generally not effective.

As for depression, the relation between the mood and CFS symptoms has been reported by many patients including Bruce Campbell. I’ve been personally noticing that the crash threshold goes up when my mood is aroused. This is probably why pseudoephedrine helps me. So I guess it’s plausible that anti-depressant could help patients with depression co-morbidity.

My crash susceptibility definitely goes up when I’m feeling more depressed, feel stuck, hopeless etc. I see that as an additional stressor on an already messed up stress response system – in fact two messed up stress response systems..

Yeah, I feel for you, Cort. I have similar experiences. Strangely enough though, the arousal from certain stresses seem to help me. I was totally focused on finding housing in NYC last summer and ended up taking 16,000 steps (!!!), yet I did not crash. (It sure was a harrowing experience though). It was only when we were all settled in a couple of weeks later that I started to crash again after taking 6000 steps. Same thing when my wife was having a psychotic episode a few years ago and had to go for an emergency evaluation. I ran around all day and still did not crash the next day.

I’ve been meaning to write up about my experience with traveling, arousal, stress etc. It’s been a terrible winter with 2 bouts with flu and all. But I’ll get to it someday soon, I hope..

Looking forward to your writeup.

Oddly enough it’s more the minor everyday stressors that seem to jack my system up and leave it in a state of arousal. I got through some big stressors pretty well as well. Some lesson in there somewhere…

Ditto ??

Hi TK,

Pseudoephedrine has one thing in common with arousal / fight-or-flight hormone epinephrine (aka adrenaline): both are bronchodilators.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pseudoephedrine

“Pseudoephedrine acts on α- and β2-adrenergic receptors, to cause vasoconstriction and relaxation of smooth muscle in the bronchi, respectively.”

That’s quite alike epinephrine, but epinephrine probably is stronger in both action and side effects.

Hyper ventilation or over breathing does with ME patients appear to be more then some malfunctioning. It has both powerful restorative effects as well as a high cost IMO. Using bronchodilators or creating your own (adrenaline) helps breathing at the cost of side effects.

For me, having better average air quality helps with few side effects: good ventilation (double so at night) without creating a cold draft or growing mold, less dust and chemicals in house, be outside when the weather allows it,… have a small effect but very few disadvantages.

Having a good posture and sleeping position that does not constrict the movement of chest or belly helps too, as well as not constraining their movements with narrow cloths. All small effects but they add up over time.

A big one was learning to breath better by going to a good professional physical therapist specialized in breathing therapy. It is affordable and should be doable for someone that is not entirely homebound. First results came only after a few months. I still need to practice in little bits every day but can now breath better with less effort automatically. That’s twice gained: better breathing and less energy needed to do so thus more pacing.

What also helped me is using breathing/arousal as an early indicator for overexertion: breathing pace/effort and arousal come way ahead of PEM in my case, offering the opportunity to prevent PEMs with far greater efficiency. Now I have one less then one a month.

Please keep making notes and sharing information,

Jurgen

“My crash susceptibility definitely goes up when I’m feeling more depressed, feel stuck, hopeless etc.”

With me its is even stronger the other way around: when I crash fast it is like in a few instants all joy for life has left my body leaving me in a state of deep despair. The closest I can describe it is as if joy and life energy were like air in the space station, with crashing a sudden 3 feet / 1 meter whole in its walls venting all air.

Think it is the highly inflammatory effect of the crash that creates this feeling of despair and hopelessness. It’s hard to tell as they go often hand in hand, but with flash crashes it’s clear it’s not caused by hours of feeling depressed. Sometimes it’s a matter of minutes going from joyful to utterly deep despair and all of it is caused by overexertion time and again.

@dejurgen, yeah I tried both. I’m borderline asthmatic and Bronkaid also helps. But Sudafed seems to work better for me. By the time my fingers turn cold, the ache and fatigue moderates. I used to think it could be the vaso-constrictor effect that squeezed blood out of muscle, but now I think it is the stimulant effect.

I call this being “hyper”. As I see it I release adrenaline (or similar) in response to a stress and I run on the energy produced by this, the body’s last resort energy for fight or flight. It is lovely, you feel better and as you say your crash threshold increases, however there is a price to pay down the line – post adrenaline blues/depression being one of them.

Aha, yes, there certainly is that borrow/repay aspect. I used to feel that way early on. In fact the adrenaline high is exactly what I said in 2010 to a woman who asked me about why she was able to weather activities better while on a trip.

It seems more complicated than that though. For one thing, I no longer pay price down the road for a short stress/high lasting a few days, even though I regularly crash after much less activities when not high. For another, the price that I pay after a longer high seems fixed. I recently went on a city-hopping for 10 mo and noticed that the post-trip struggle after a leg always lasted about 3 weeks whether the leg was for a week or 2 months. And the struggle always ended immediately without a repercussion if I get right back on the road. So there seems to be more going on than just borrow/repay phenomenon.. It could be a CFS version of post-trip blues commonly understood as a mental depression about getting back in the rut. But the post-trip blues are supposed to be proportional to the length of the trip and doesn’t usually last that long. Moving to NYC isn’t exactly getting back in the rut either.

Anyhow, this is but an anecdotal experience of one person. But I’m thinking modeling the responses to various type of stimuli could give us some clue as to what’s going on underneath. And that’s my current project, though I’m far from certain that I’ll succeed..

It’s worth noting that anti-inflammatories like NSAIDs are contraindicated for conditions such as Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis, so not everyone with high inflammation levels should have them.

I have been on Rituxan for two years it helps with the rheumatoid arthritis but not for the CFS. Still looking for answers with that ?,

I think I need to have Dr Klimas see me, she could tell me what’s going on with my immune system?. I truly would like to have her examine me.

She’s the one to go to for immune testing. I hope you can get to see her…

I take celebrix quite often for ank spond and it does seem to mildly wake me up, reduce fatigue and – I had also concluded from other experiments – boost central dopamine transmission.

Works particularly well for getting rid of that post too much caffeine wired/tired feeling.

That being said its benefits are fairly minor and I still rely on vasopressors (phenylephrine 20-30mg doses) and central dopamine meds as needed to be functional.

Interestingly i have noticed that Celebrix ‘feels’ a lot like Rhodiola and Licorice.

I had a cold a few months back which relieved my multi-year, extreme mental tiredness at the 3rd day in mark.

It lasted for 3 days during which I felt myself coming back online. I was weeping with joy and the restoration of feelings that had been dormant and they all so readily came back. I could talk and think without tiredness. I’m aware that my thinking is flat but this sudden change was such a contrast, that it really hit home. So many dimensions of thought were returned to me. Could really think so clearly.

After three days, I awoke with that knowing that the cold was over. I sat down feeling good that the cold was over, started talking to my girlfriend and suddenly drooped. Mental tiredness came on. Such a disappointment and also so much hope, to find so much waiting for me so closely.

Went on Phoenix Rising to read others stories of similar that I remembered reading years ago. Have had colds since but no relief of the same sort. Would be fascinating if I could achieve this medicinally.

“salt water placebo”

Salt water is kind of an oral saline administration. IV saline has clear short term effects on people with ME. It also has long term effects https://www.healthrising.org/blog/2017/04/15/saline-pots-chronic-fatigue-syndrome/

“At some point 50 of the participants reported no need for further infusions, except during times of stress, within six months of starting the infusions.”

If ME and depression both would have strong ties to inflammation then there is a possibility that they both respond to similar “medication”. In fact, many drugs administered to ME patients are administered to people with depression too.

Many inflammatory disease like arthritis and diabetes have a strong link to too much purines in the blood. Too much purines has a strong correlation to too much uric acid in the blood, as uric acid is the breakdown product of purines.

Sodium bicarbonate has a strong effect on reducing uric acid levels in the blood according to https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2845176

Sodium bicarbonate isn’t the same as sodium chlorine used in saline, but IMO much of the sodium bicarbonate is produced from sodium chloride in the body so increasing salt intake could/should effect sodium bicarbonate levels.

As to the inflammatory effect of uric acid crystals https://arthritis-research.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/ar4026:

“Patients with anemia had a two-fold increased risk of developing gout over nine years” -> gout is a purine based disease; anemia has a very strong correlation to hypoxia -> so hypoxia could increase uric acid crystal formation in capillaries… reducing blood flow in them… increasing hypoxia… increasing uric acid deposits… …creating a potential vicious circle.

Both depression and ME are associated with vicious circles. Depression a strong one “caused by thinking wrong”, ME an extremely strong one.

Maybe it’s time to research cheap, available and unpatentable increased salt administration?

Like increasing “public health enemy” fat intake can yield good results for some ME patients (keto diet), increasing “public health enemy” salt intake might help select patients.

Reading the above comments,brings up several respnses and questions for me.

1. I have also wondered if part of my health issue is oxygen related. I do have some lung damage due to previous infections.

2. Sudephed also helps me with energy as does tyrosine.

3. My chiropractor recommended an omega 3 and omega 6 test for inflammation. As a result I am taking high does of omega 3. Now, not sure if that is correct.

4. How and what do you test for inflammation? I was given a prescription for Avara for inflammation but am hesitant to try it.

5. Histamines as a factor in depression were mentioned. How do you test for tbat?

Any responses would be appreciated! I am learning so much from all of you.

For ME, there is IMO no known reliable inflammation test. Very few ME patients without co-morbidities have increased “traditional” inflammation markers, yet our disease more *resembles* an inflammatory one then an anti-inflammatory one.

Personally I *believe* we have a suppressed inflammatory disease, where both strong pro- and anti-inflammatory elements are available.

When it comes to omega-3 I do take low to moderate doses to supplement. The idea I use is that western diet is skewed very strong towards omega-6 (compared to pre-industrial diet), and that moderate amounts of omega-3 supplements still keep the ratio omega-6 to omega-3 too high according to most research.

While making this choice, I only reduce the potential extreme without risking to reverse the ratio. When in doubt I try to keep away from the extremes. More info on how much our diets tend to very high omega-6 to omega-3 ratios is found here https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Omega-3_fatty_acid.

If such reasoning is better than tossing a coin, that is the question. Can’t say I feel omega-3 supplements help, but they at least don’t seem to harm me.

Mast cell expert Theoharis Theoharides published an article titled “Chronic Fatigue Syndrome, Mast Cells, and Tricyclic Antidepressants” that has some relevance to this topic:

“Tricyclic antidepressants have been reported to be helpful [for CFS] at concentrations lower than those typically used to treat depression.”

“We hypothesize that corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) and other related peptides secreted by acute stress, activate diencephalic [a part of the brain that includes the hypothalamus] mast cells, either directly or

through neurotensin (NT), leading to the release of proinflammatory cytokines that contribute to CFS pathogenesis”.

“Mast cells and their mediators have been implicated in diseases that are comorbid with CFS; in fact, there may be altered mast cell function in some tissues of CFS patients.”

This article was published a dozen years ago, but researchers and clinicians still have no interest in mast cells. This is a real shame, since for me, anti-histamines make the difference between being homebound and bedbound.

p.s. I found this article on ResearchGate.

The CDC website now says: “Some people with ME/CFS might benefit from antidepressants and anti-anxiety medications. However, doctors should use caution in prescribing these medications. Some drugs used to treat depression have other effects that might worsen other ME/CFS symptoms and cause side effects.”

So do make sure your doctor is fully aware that antidepressants can actually worsen ME/CFS.

How so? I believe you, but I have never heard about the mechanisms for this… thanks.

If I need to exercise I find panadol (acetominaphen) can be a small help in avoiding consequences.

Interesting! An anti-inflammatory. I have suspected for years that exercise increases inflammation =- that’s what Dr. Klimas is finding – but I think exercise leaves me actually looking “puffy” and swollen a bit.

Cort, the inflammation from exercise can last several days. They come in waves in mutiple stages, to repair the damages. This test was done with intense exercise, but even the most mild exercise will provokes similar, albeit milder, immune responses.

https://journals.lww.com/nsca-jscr/Citation/2016/02000/Exercise_Intensity_and_Recovery___Biomarkers_of.3.aspx

Taking Ibuprofen before intense exercise does work. I used to do that when I was competing. It doesn’t seem to make difference for slow walk though, which is the only exercise that most cfs patients can muster. But I think I’ll give it another try since JM is reporting the difference.

Thanks for the tip. It makes sense that anti-inflammatories might help. I will give ibuprofen a try.