You don’t need to be a large organization to make a big difference. You simply need to be committed to a field (and producing jaw-dropping results doesn’t hurt either.) Consisting of three exercise physiologists (one with ME/CFS), a clinical coordinator, and working with one of the top chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS) experts (Dr. Dan Peterson) in the world, the small Workwell Foundation has and is playing a seminal role in the chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS) field.

The recent metabolomic and energy studies – that have galvanized so much interest by highlighting problems with energy production – are simply the logical conclusion of the exercise test results Workwell pioneered with Dr. Dan Peterson over 15 years ago. Workwell’s exercise tests uncovered an energy deficit that may be unique to ME/CFS and helped make exercise a key component in dozens of ME/CFS research studies. The Workwell Foundation’s work with Dr. Todd Davenport resulted in a seminal paper on ME/CFS and physical therapy which has helped many physical therapists embrace ME/CFS.

For many though, Workwell’s influence has come at a much more individual level: their exercise tests have assisted many people with ME/CFS and/or fibromyalgia (FM) in winning their disability battles and getting crucial financial support.

The second part in Health Rising’s series on The Workwell Foundation focuses on one of the most agonizing yet impactful battles many people with ME/CFS/FM – winning their disability claim.

The Disability Battle

So you’ve got a bad case of chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS) and/or fibromyalgia. You’re so sick that you can’t work anymore. Thankfully we don’t live in medieval times. We have systems designed to protect the ill among us – systems that will at least ensure that we’re not starving out on the streets simply because we were unlucky enough to fall ill. Right?

Getting disability in diseases like ME/CFS and FM isn’t easy but Workwell’s testing can give you a leg up.

Not so fast. The purveyors of those systems, whether they be the federal government or private insurers, aren’t going to take your word for your inability to function – they want you to prove it. In fact, the private insurers will take and twist any scrap of evidence they can find in an attempt to prevent you from proving it. They’ll bring in their hatchet men (doctors), they’ll surveil you, and they’ll deny you and just hope you go away.

Plus, you of all people have a particular problem. You have a controversial disease that doesn’t have the kind of medical validation that other diseases do. Proving that you’re too functionally limited to work isn’t easy. It’s basically your word (and you hope) your doctor’s word, plus whatever test results you can muster up against a hostile insurance company and a judge that may view your case with some skepticism. You can throw most of your expensive test results (pathogen screens, cytokine, NK cell, cortisol tests, etc.) in ME/CFS right out the window – none of them prove you can’t work.

You hope that your doctor writes a good report, and that you crossed your T’s and dotted your I’s, and you pray you get a good judge. It’s kind of a crap shoot – one with potentially immense consequences.

Workwell’s Two-Day Exercise (CPET) Test

As a cornerstone symptom of CFS, it is imperative to document post-exertional malaise in order to objectively demonstrate the inability to work on a regular and continuing basis. Workwell

The two-day CPET test provides a true test of functionality that the courts almost always accept. Steve Krafchik, an ME/CFS/FM disability attorney in Seattle says he’s never lost an ME/CFS/FM case featuring a positive Workwell CPET. Before we get to the exercise test that can help you win your disability, though, we have to go over the exercise tests that can do the opposite.

Exercise Tests That Hurt

Other exercise tests (one-day exercise tests, submaximal exercise tests, treadmills, step tests) will probably not only not reveal the energy problems present in ME/CFS, but can sound a death knell for an ME/CFS/FM patient’s attempt to get disability.

One ME/CFS patient with documented pain and fatigue problems failed to receive disability when she passed two other kinds of exercise tests – a one-day exercise test and an 8-minute treadmill test. (Yes, the court agreed that walking 8-minutes on a treadmill indicated that this person demonstrated “normal functioning” and could return to work.)

In another near tragic case, an ME/CFS patient’s primary care doctor and three other MDs (including one from the Social Security Administration, a private insurance carrier, and a state retirement board) agreed that she was disabled, yet the court, using the findings from a treadmill test and a medical advisor who had never seen the patient, rejected her claim to disability. (She ultimately won on appeal).

Disability was rejected in another ME/CFS court case because the submaximal one-day exercise test results – which did indicate a detriment – weren’t strong enough to counter the video surveillance of the ME/CFS patient driving his car, shopping, etc..

Anyone required to do these tests by an insurance company is likely in desperate need of getting a true test of functioning done – an exercise test that can help instead of hurt – to counteract those findings.

The Exercise Test That Helps

Each of these ME/CFS patients failed to get disability because the courts confused a single exercise test with a

true test of functionality, but a single exercise test simply determines whether a person can function normally one time.

Many people with ME/CFS/FM can “show up” one time; it’s the second, third and fourth times where the real problem – the post-exertional malaise – kicks in. Workwell’s 2-day exercise test is the only test which shows that exertion impairs an ME/CFS/FM patient’s functioning and provides objective medical evidence to do so. It’s Workwell ability to medically document this that makes their reports so effective. Their two-day maximal exercise test is able to demonstrate that ME/CFS/FM patients can’t be expected to engage in even sedentary work on a regular basis.

Submaximal exercise tests don’t work because they require that a submaximal effort be put forth, which allows insurance companies to suggest the low scores are a result of malingering – planting doubt in a disability judge’s head. Because Workwell does a maximal exercise test, insurance companies can’t use this ploy.

The fact that the submaximal exercise test they do is actually a pretty puny test only works in Workwell’s favor. It doesn’t take a brain scientist to understand the gravity of what Workwell’s tests are showing. Most of the ten minutes or so spent in the exercise test are spent in a low ramp-up period which requires mild exertion. Only during the last couple of minutes does the exercise really ramp up. If your system can’t recover from that little bit of stress by the next day, it’s really impaired.

Those few minutes, though, are apparently enough to take a two-by-four to many ME/CFS/FM patients’ ability to produce energy. One early ME/CFS study found almost a 25% drop in energy production – a remarkable decline in the ability to produce exercise – after spending a mere 10 minutes or so on a bicycle.

A second, larger study found a huge drop in something called “work efficiency”. That suggested that ME/CFS patients were spending a lot of oxygen and not getting a lot of energy out of it.

The CPET Test

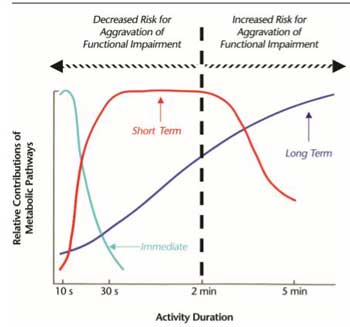

Workwell gets a bevy of data from its exercise tests but two key factors, VO2 max and the anaerobic threshold, hold the key to their disability reports. VO2 max measures an individual’s peak aerobic capacity – how much energy their system can generate when it’s going at full bore. Anaerobic threshold measures the point at which a person transitions from generating energy cleanly and efficiently (aerobic energy production) to where they’re relying on the much less efficient (and toxic) anaerobic production of energy.

The dark blue line curving up to the right refers to healthy people. The red line shows what happens to many people with ME/CFS/FM as they exhaust their aerobic capacity.

The two main facts to get are that: a) the aerobic metabolism burns O2 and produces lots of clean energy, while; b) the anaerobic energy production burns glucose (glycolysis), emits lactic acid, produces little energy, and makes you feel like crap. Both systems are going almost all the time but if you’re going to do something like exercise, or even be active, your aerobic system has to be functioning well. If it isn’t, you’ll quite quickly get fatigued and be in pain. That’s the situation that Workwell often finds in chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS).

Healthy people respond to exercise by producing voluminous amounts of clean energy, but with their aerobic energy production system crippled, people with ME/CFS/FM fall back on their anaerobic energy production system.

Now, lactic acid and hydrogen ions build up, producing fatigue, muscle burning sensations and pain. The body combats that buildup by generating C02, which is exhaled through the lungs. It’s this increasing emission of CO2 which signals to Workwell that a person’s anaerobic threshold has been reached. When that happens, energy production slows to a crawl and every bit of energy produced is going to come at a cost.

It’s the anaerobic threshold that is the measure which really cements disability for many ME/CFS and FM patients. An early anaerobic threshold simply means your ability to produce energy is severely limited. A significantly reduced VO2 max/anaerobic threshold on the second day means you can’t generate the energy to work – which can even include sitting up – consistently.

The Disability Report

I had the opportunity to read one of Workwell’s CPET reports. It was a 12 page document full of statistics, charts and analysis.

In their summary, Workwell demolished any attempts to show that this person was simply deconditioned. Then, they turned to the crucial factor of functioning. Because the ability to function in a sedentary job precludes a person from getting disability, Workwell needed to show that this person was unable to do that — and they did. They noted that:

“Most activities of daily living (reading, normal speed walking, computer use, office-type work) are aerobic in nature and healthy individuals are able to perform such activities for prolonged periods of time with no meaningful physical fatigue.”

But this patient X’s test scores indicated:

“That even light work will demand more energy than can be aerobically produced. Many normal activities of daily living would severely tax “patient X’s” capacity to produce energy aerobically… These results … preclude “patient X” from engaging in light or sedentary work in a consistent and reliable manner”.

Workwell’s been filing disability reports like this for over a decade. Recently, their exercise testing reached a new level of significance as it figured prominently in a federal disability case recently won by an ME/CFS patient.

The Brian Vastag Case

Brian Vastag was recently put through a disability torture session by Prudential Life Insurance. After Prudential dropped his short-term disability benefits, it then denied his attempt to get long-term help. After losing several appeals, Vastag went nuclear and filed a federal lawsuit against Prudential, citing the Employee Retirement Income Security Act of 1974.

The case report is instructive in the lengths to which an insurance company will go to deny a disability claim. Remarkably, Prudential used a nurse practitioner’s interpretation of Vastag’s medical data to reject Susan Levine MD’s assertion that Vastag was unable to work.

Next, a rheumatologist argued that Vastag’s findings of active herpesvirus infections were borderline abnormal and did not explain his fatigue or cognitive decline. The rheumatologist concluded that Vastag was not disabled because he had not demonstrated “objective evidence of total disability”.

Brian Vastag undergoing testing during the NIH Intramural ME/CFS study. Prudential repeatedly denied Vastag’s claim. Workwell’s exercise testing helped Vastag win his court case….

With that, Vastag visited Workwell to get an exercise test, the Zinns to get a brain scan, and Sheila Bastien PhD for a neuropsychological exam.

Workwell determined that the poor functioning Vastag displayed during the 2-day exercise test “severely limits his ability to engage in normal activities of daily living and precludes full-time work of even a sedentary/stationary nature.”

Even with that, Prudential denied Vastag’s subsequent appeal. While the occupational specialist agreed that the CPET testing did indicate abnormal fatigue, Prudential denied its validity because the CPET findings were not diagnostic for CFS – the condition Vastag was applying for disability under.

Vastag replied by filing a federal lawsuit against Prudential in May 2015. In the 32-page ruling released on May 18th of this year, the judge relied heavily on the Workwell report and the “gold standard” CPET test it used for “measuring functional capacity” and the “objective medical evidence” it provided, which demonstrated Vastag’s impairment.

The judge called Prudential’s conclusion that Vastag failed to demonstrate “any impairment” in his functionality “perplexing”, particularly in light of the physical abnormalities she reported that Workwell’s CPET testing “dramatically” demonstrated. She singled out the exercise testing for providing “objective evidence of the limitations of Vastag’s functional capacity”. The judge also dismissed claims by Prudential that because CPET exercise testing was not diagnostic for ME/CFS, it should not figure in his claim.

Laying down a judgment – which hopefully lawyers will use in decades to come – the judge further castigated the Prudential lawyers for missing the key symptom Workwell’s test is designed to document – post-exertional malaise.

With that, Judge Katharine S. Hayden of the U.S. District Court of New Jersey ordered Prudential to remand all benefits to Brian Vastag.

- Next up – Disability and Workwell II: Disability winners on how they did it and a talk with Dr. Chris Snell

- Workwell’s Website

- Workwell’s Contact Info – info@workwellfoundation.org / Phone: 209.599.7194 / Fax: 209.599.4047. Workwell is based in the Central Valley in Ripon, California.

- Check out Health Rising’s Disability Resources Section

Health Rising’s Workwell Resource Page

-

The Workwell Foundation Resource Page for Chronic Fatigue Syndrome – including Health Rising’s blogs on Workwell, plus Workwell resources including articles and videos on exercise, PEM, activity management, disability, physical therapy and the dangers of graded exercise therapy.

This is great news! I don’t think I would have any quality of life left without the financial support I receive. The support allows me to use pacing–in my opinion the best help for many ME/CFS symptoms.

While being treated at UCSF pulmonology department over 20 years ago, I was referred to Dr. Dan Peterson to test me for CFIDS using this exercise study. Dr. Peterson helped me understand what was happening to my body and suggested I start physical therapy. My primary care doctor was very impressed with the study. Because of Dr. Peterson and his study, I was approved for Social Security Disability. Also, because of this study, my long-term disability company reluctantly approved my disability claim. Thank you, Dr. Peterson, for your dedication to a condition the majority of the medical field denies.

Dr. Peterson has long been a leader in exercise testing. He’s been working with Workwell for decades.

Please be careful with this ruling. From what I saw, the court only awarded him retroactive benefits and sent future benefits back to Prudential to determine if he could do “any job”. This is not the be all end all case for CFS.

Good catch. I had missed this. The judge referred the case back to Prudential for that reason while requiring them to pay him Pass benefits. The judge did note in her report that the exercise testing indicated that Brian was unable to engage and normal functioning. It’ll be interesting to see what Prudential does given the judges strong endorsement of his testing results. Hopefully Brian will not have to go through this again.

I can only thank God Vastag had the intelligence and the will to fight despite the tremendous legal and moral injustice Prudential waged against him. His ultimate victory and legal vindication surely will help many others being cruelly denied the SSD they have a right to expect, based on their indisputably weakened bodies which are consumed by CFS-ME.

As a woman who recently had to fight seven years and seven months myself for Social Security Disability because of my little understood connective tissue disorder, Ehlers Danlos syndrome, I know much of what Vastag endured. It’s a horrific torment to tell the truth and be disbelieved. It’s mind boggling to see your credible medical and psychological evidence tossed aside like mere feathers. It’s disheartening to realize some ALJ judges are highly immoral and sneeringly corrupt individuals who’re openly sadistic, comforted by the fact they’re appointed for life.

But, then again, it’s indescribably beautiful when justice finally appears.

I’m feeling similarly exasperated over my health status and my insurance company’s conniving, presently, regarding my seeing a number of specialists. And I am paying more per month and per co-pay so I could have the option of better specialists, yet the insurance company (Humana Medicare – Part D??) seem to be in the makings of sabotaging my health care. This agregious treatment is not what I intended to pay more for.

THANKS SO MUCH! I have just finished a ‘field interview’with my insurer and if they still don’t pay I now have this option. What we do without blogs like this one!

It’s been too long since we had a Blog on Workwell’s fantastic disability work. Good luck!

I had the workwell CPET done and it was a great report. However I have showed it to two doctors and a cardiologist who refused to comment on it in their records saying they weren’t familiar with it and therefore couldn’t comment on it. And without an MD to “comment” on it… it means nothing to ss. I just cannot find an MD to listen to me. And lawyers have told me that my NP won’t be enough.

Hi Joanna, my doctor wasn’t familiar with the testing either, so Betsy Keller PhD, who performed the testing and wrote my report, kindly agreed to have a phone conference with my doctor to answer any questions. Maybe that’s a possibility for your situation?

HI Birdy

Did you participate in the Ithaca study? Did it help your disability claim?

Dorothy

That’s unfortunate and I don’t know what NP is but while the report may by itself not be enough it is not nothing. The report does presumably clearly state that you don’t have capacity to engage in normal living and work.

The judge in Vastag’s case repeatedly referred to the report and quoted sections from it. (She also referred to Dr. Levine’s interpretation of the report but not as much.)

I guess neither of your two doctors or your cardiologist are willing to speak with Workwell? I assume that none of your doctors are able to help much – but are not willing to take the time to talk to Workwell to understand the report to help you not end up in the poorhouse. That’s kind of horrifying! A ten minute call could mean so much to your future.

I wonder if giving them the Vastag case would help? Or perhaps you can put off the disability and find an ME/CFS expert who will testify as to the veracity of the report (???)

I got a reply from Chris Snell of Workwell:

“It’s called research. Perhaps we should tell them about the internet!

A Google search specifying “2 day cardiopulmonary exercise test” produces “about 2,120,000 results”. The first entry states: “Two-day cardiopulmonary exercise test or 2-day CPET is an accepted, reliable test for post-exertional malaise (PEM).” This entry includes a discussion of the 2 day CPET including further links, supporting evidence, references and a citation from the Institute of Medicine (IOM: now National Academy of Medicine, NAM).

Not all of our patients’ primary care physicians accept that they are actually sick. I recall one case recently where the PCP would not sign that the patient was impaired because he did not understand the CPET.”

Staci Stevens reported that

“I would also add that the Social Security ruling for CFS states that an abnormal stress test is an objective finding for a medically determinable impairment. So while it is helpful to have an MD comment positively on the report it is not required. A good attorney can use the ruling to support abnormal CPET.

However, there is never any guarantee that a physician judge, or attorney will understand CFS, the SSA ruling or CPET. They each require research. Our 1 page report bibliography provides all the evidence anyone should ever need for any of these purposes. Making them “believe”, well that is another issue.”

I wonder if the possibility of faring better regarding being approved for disability income by highlighting any and all (triggered) brain fog issues would help, by seeing a psychologist or psychiatrist. Someone disabled told me any psyche issues were easier to ensure being approved for disability income. Just a thought, but that concept seems rediculous, probably (& demeaning, to simply not be believed). It’s unbelievable, really. Even my pediatric neuro. N.Practioner daughter didn’t want to acknowledge the fact when her Mother tells her of how she’s suddenly been rendered in bed, most all of her days, that I’m really and truly in a disastrous state (especially with no kids living near me to help me in any way). And so it goes. Preposterous, really.

Just wanted to share that, at least in 2016 when I had mine, Betsy Keller, PhD was also performing two day CPETs at Ithaca College in NY. I don’t know if Dr. Keller is still available for private testing as she is now co-director of the clinical core at Maureen Hanson’s Cornell ME/CFS Collaborative Research Center. It’s worth looking into if your considering testing and are closer to the east coast though.

Dr. Keller’s excellent testing and thorough report provided hard evidence of my significant impairments, and most importantly, why I am incapable of working. I’m sure it’s the main reason my disability income was approved.

Just to be upfront, another supporting factor for my approval was that my ME/CFS developed while I was undergoing chemotherapy for breast cancer. I was ill enough that they stopped giving me the chemo, which puts me at greater risk of recurrence. Guess that took the malingerer argument right off the table.

Anyway, another positive outcome of the CPET testing was that it proved to local physicians there really was something wrong with me, even if they didn’t understand it, they accepted the test results. It gave them rock solid footing to say I was incapable of working when they filled out the disability paperwork.

Unfortunately the testing and travel resulted in a severe crash. Two years later I have yet to recover to pretest functioning by a very long shot. I’m not sure how often that happens, but it happened to me, and it’s something to consider. Rock and a hard place.

For me the system worked the way it’s supposed to; it’s my dearest wish it would work that way for everyone. Best wishes to all.

I had a LTD policy provided by my employer which was to pay 2/3 of my salary until age 66! Not so they fought me on all of the documentation submitted by 3 different Dr’s of mine that all said I was unable to work. They did not want to pay me at all period. They decided that I was only allowed 24 months of LTD based on having limits on every symptom from A-Z. After my 24 months I appealed and got a denial letter saying “our Dr has determined that there is no reason why you cannot sit in a chair 40 hours per week! I was 51 at the time so I felt totally cheated especially since my former employer had encouraged me to take advantage of this LTD benefit policy. On the other hand I was not denied by Social Security which I had been told to expect. That they denied the first claim for everyone. When I told this to the members of a CFC/FMS support group they were amazed & joking said it wasn’t fair. Still the difference in SSDI versus 2/3 of my salary was a huge drop. It seems to be that no matter what type of insurance you have car, home etc once you file a claim you have a huge fight to get paid for what you thought the policy covered. I hope this nightmare of insurance companies denying benefits will get better for all of us especially when our lives have already been shattered by a chronic illness we have no control over.

Hi!

This all sounds so positive, but are these tests available in the UK?

Getting disability benefits (PIP- personal independence payment) are very difficult to obtain here with a diagnosis of ME/CFS for many patients. I’m just at the start of the process?.

Many thanks.

Fiona.

Good day.

Please see attachedments I would know if you can help me to improve my conditions and memory loss problems.

Also if you can guide me with professional help/research / sponsorship /counseling / amino acid medication/ nootropic medication/ any support please to sell my story or improve technology

I was 21 when I jump infront of a train and had major head injuries and if left me paralysed for a few months or soo. I am a 48 year woman who worked for Nebank for 27 years then this traumatic events started . We were moving office from one floor to another and I fell up the stairs with boxes in my arms and aged 22 bumped my head that time my colleague laughed and said they never heard of a person falling up the stairs but only down the stairs.

The doctor that time said my tumours is inherit from 3 generations meningioma and malaama passed and is stress related and he suggested that we move out of the residential area. Which we did. But neverless I lost everything my husband my beautifull plot my children my friends all my personal en sentimental belongings due to my personality changes, emotional insecurity, social phobia, memory loss, Nobody understood me not even me do now. I had 4 brain operations due to genetic gene’s, over a period of 15 years. The first in 2001 half of my hair was shaved of to open my scalp to remove the tumour, the second 2002 the back of my left ear that leave me partial deaf the 3 rd in 2011 on my frontal right lobe eye what started with losing my eye sight the last in 2015 in my right frontal lobe.. which created a personality change which canot accept nor can my family. Which i am losing my eye sight I think the last one was the most difficult one due to my age and it created a personality change which is difficult to accept by myself and family and I am scared for people that I did not know before the operation. I have no words to explain my condition, I cry every day and is tired and sleep most of the time. I am unbalanced and dizzy if I stand to long I cannot even go shopping. I went through a divorce and into a relationship which made every thing worse as I did not understand why are everybody treating me like a baby. It felt that all know something but dont want me to know. I believed I was crazy but my family resued me. Well I believe I am able to cure with professional help / sponsorship or even if reseach is done on me to better technology. I want to be better a person with wealth and health and happiness and success and love than before. I am under 24/7 care but believe I am able to heal 100% with God on my side and professional help. I constantly change living arrangements within the family as they do not know how to handle my moods and cannot live by myself . I have emotional issues as I cry a lot and my family want me save and happy. I have short term and long term memory loss and it seem that no one understand me and I have no reason to live anymore. I was once admitted to Akeso Clinic and one in Randvaal area but I turned out worse and know i am with family in Heidelberg always family with me 24/7 as I get lost and all funny things happen to me. So I am never alone….. I were everywhere with the family Durban Cape town but had no professional help just loving family protecting and caring for me for the past 4 years.

The Brackenhurst clinic referred me to Alberton North physo who wanted me go go to Sterkfontein hospital but my family said noooo

Once a month the family comes together and dress me up and make me beautifull for photos but that makes me even more emotional. They love me soo much and also want to see me as I use to be and I know I am breaking theirs hearts as they see me deteriorating . Please see attached documentation and advise accordingly. Your help will be much appreciated. I am positive that this will be sponsored as I want to heal but the financial is limited from our side . I also believe that a book can be written as this is generic from our past 3 generations as some of my nieces and cousins sit with the same issues but not diagnosed or as severe as mine This would also make a great testamonial or a motivational speech. . But I do not no where to begin and need professional assistance.

As I know I won’t ever be able to work due to this condition i have. I have both short and long term memory loss. I mix my words and numbers and are a threat to myself at home when left alone as i forget to put off the stove and to close the bath tap and forget who is who i drink the wrong tablets etc. I need my family or fiance to give it to me on regular basis I think it could be the beginning of altzheimer or something that is similar.. I do not want to be a burden to my family and want to know if there ever be a possibility that I can live a normal life again . I come out of a loving family with Christian upbrings and they support me 100% If not can you direct me in the right direction please. I am sooo scared and cannot go on this way of living I beg you out of my deepest heart to help to be a normal happy person again.

I know I look normal but the problem is inside my confusing head and I cannot think as I used to think and do not remember what and when I do what and forget what I wanted to say someting.

The knowledge I havr cannot be tsken away from me but My brain have difficulty to accept new information…

Nedbank authorised me to apply for a disability grant at Sassa

Jimmy Abbotte referred me to Nasa Smartmind in Heidelberg who is doing case studies on me currrently.. as I have breakdowns and loose count of 4 or 5 days at a time.. I know i am high maintenance but do not want to be a burden or a laughing joke to anybody.

God is good….. All the time….

I cannot go on living this confusing,depressed, joint stiffness,scary,trustless, helpless, suspicious, emotional, anxious, panicfull, frustrating, irrational, dizzy, impatient, way.

[02/28, 10:48] ICAS also referred me to Sanca in Heidelberg who said they will refer me to someone else. I am still waiting for their call…

[02/28, 10:55] Vic: Icas reference me to Sanca in Heidelberg again 27/02/2018 and their response was the same as the last time. They cannot help me as my case is to complicated with my brain tumour and injury and with my long term memory and short term memory loss. But they gave me 2 numbers for dr in Vereeniging and in Alberton which my fiancee must phone for help.

He did phone but one is over seas and the other one works on a cash basis which I cannot afford.

Currently I am on prolax and epynoutin from the gov hospital in Heidelberg, Gauteng.

I buy solal amino acid naturally high now, I used hpt5 before

And i also drink IPS energy tablets.

Please help me with correct health supplements to become a normal me again. ..

I have recurring genetic multipule meningioma tumours and malamoma skin cancer inherent from 3 generations passed accordingly dr Snyckers,dr zorio and dr Torres-Holmes from Milpark. And they also said my brain do not produce serotonin any more.

My name is AV TROLLIP and my date of birth is 18/06/1968. I live in South Africa.

I got your info from the Internet

I am busy writing my story for 3 years now…

The dr said I must write everything down, and I am 50 years old now and I think I am getting better as I am starting to accept my personality changes and God knows what He has planned for me…

I meditate every night and listen to sounds to rewire my subconscious mind….i believe I am in a awakening stage but still very confused ..

I know get my meds from Heidelberg gov hospital . The dr psychic at Heidelberg referred me to the Psychiatrist in Ratanda dr Thoka who want to atmit me to Tara in Sandton but must first have a panel interview with various drs at Sandton and a discussion with my family…..

I also try to live in the moment every day….i am a new me and want to grow further please help me as i need help to improve faster in my subconscious mind. Maybe i also have ME as i am contstantly tired and sometimes sleep fot days if i had a budy day

I wonder if ginkgo biloba might help with your memory issues as it has helped me in the past and I should, therefore, get back on it again. I, too, can forget what I’m saying in the middle of a sentence, especially so, if interrupted— more so lately, during a time of added health issues, which seems to have exacerbated my focus/concentration or memory. I was diagnosed with “CFS” around 2012. And it does not affect my intelligence, either (I believe I’ve read that to be so). Another aspect helpful to my brain and body functioning is that I tried 3 things early 2018, when my status notably improved:

1- a higher dose of B-12 lozenge, which is known to help energy levels, generally speaking,

2- going low gluten (& even more low carb by going very low grain— ME-CFS folks don’t process carbs properly),

3- my new rheumatologist prescribed a low dose of gabapentin, which, I felt it helped my brain and body (muscularly) function in a more fluid, easy manner.

These concepts worked for me, mind you and your brain issues are different from mine, but I figure if these ideas WOULD help you— great (if you also might have ME-CFS). Pacing any and all activities, even socializing, in a very, very slow paced, a very, very reduced manner may be something you could try, as well. I prefer to rest all night via sleep and rest through my day ‘til evening when I do well to get up from bed to accomplish 2-3 hours of tasks, especially if they require standing, as I have been “tilt table tested” (an easy test prescribed by my cardiologist, given at a hospital), which is a sort of standing disability that some ME-CFS folks have.

Even if I sit and chat or chat on the phone for a long one hour phone call I can find it difficult to even get one task done afterwards without great difficulty, if at all. So I don’t even keep in contact via phone with my 5 siblings. Watching t.v. almost all day & engaging in Facebook, some, seems to keep me resting for such long periods without going nuts. I try to use the television to keep my mind off of negative thoughts, which, it is very useful for this.

Exhaust all measures, dear, and best wishes. Any progress is a good thing, even in simply adapting better to your circumstances, as you seem to have made progress in doing. I’ve heard enjoying nature or resting in bed for 1-3 days can be good for neurological issues (& it helps reduce fatigue or help to re-charge folks with ME-CFS— at least, it helps me). I usually need to lie in bed all day, once a week.

I only can accomplish:

• One load of laundry/day or

• one shower/shampoo/week, or less

• hardly cleaning one room/week or less

• I don’t pay my bills by checkbook & do not do online bill paying, usually, so I drive to pay them in person, since my brain doesn’t function well

• I use motorized carts through big stores, where usually provided, or rest before and after an errand through a small store.

I would Love to be healthier as it has been a travesty, trying to keep up with being a new Grandma and dealing with activities regarding showers, weddings, etc., with my 2 kids. It sucks that I can never get physical help from them as I have needed, as they not only don’t get how badly I need their help but they have both move out of state or almost out of Florida, USA.

I have not been properly caring for myself or my home at ALL, these past long 8 years since I so suddenly was rendered mainly bedridden. Prayers for us all, right?!