Thanks again to Veronique for providing her intriguing take on chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS). This is one of a series of articles from Health Rising which feature hypotheses created by health care professionals with ME/CFS or who are associated with ME/CFS. (It is a long post – you might want to use the print or PDF options at the bottom left of the article to print it out.)

- What if ME/CFS is an Intelligent Process Gone Awry?

- Could Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS) Be a Chronic Form of Sepsis? (Dr. Bell – ME/CFS physician)

- The RCCX Hypothesis: Could It Help Explain Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS), Fibromyalgia and other Diseases?

Veronique Mead

Veronique had a very gradual onset of ME/CFS beginning in the 1990s when she was a family physician. Her symptoms worsened slowly over 10 years. At her worst, activities such as sitting, standing, taking a shower, or talking exhausted her.

Veronique, a former physician, has had ME/CFS for about 20 years.

Using her experience as a guide, Veronique has been researching how the nervous system’s perception of threat can be an important and under-recognized contributor to chronic illnesses. Not because chronic illnesses are psychosomatic or that being sick is our fault – but because studies indicate how events can shape our genes, our biochemistry, and our nervous system functioning.

Her work is informed by her background as an assistant professor of medicine; published research; an MA in somatic psychology with specialties in traumatic stress and body based psychotherapies; work with clients with chronic illness; as well as her own experiences with debilitating chronic illness.

Check out Veronique’s website here.

___________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

This post draws from UC San Diego’s Dr. Robert Naviaux’s cell danger response (2014, 2018) and his 2016 study documenting statistically significant, objective, hypometabolic changes in chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS for myalgic encephalitis). These findings clarify how this very real physiological disease is not psychological and how it reflects death-like states similar to freeze and hibernation.

Naviaux’s cell danger response offers insights into why so many people with ME/CFS may improve but not fully recover despite paying extensive attention to helpful treatments such as mitochondrial support, sleep hygiene, dietary changes including ketogenic diets, working with the gut microbiome, addressing leaky gut, stress, thyroid, adrenals, cortisol levels, toxin exposures, infections and beyond … and why many others have trouble tolerating these interventions.

This post expands on Naviaux’s description of the autonomic nervous system and its important role in creating these survival-based states, using the well established science of polyvagal theory. You can download a pdf of this post at the bottom or a free kindle version on my blog.

A second post citing research in epigenetics, brain development, embryology and more will further explain how some people develop ME/CFS when others with exposures to similar environmental stressors such as infections, toxins, chemicals or adversity do not.

A third post will discuss implications for treatment.

Introduction

Many people with ME/CFS have at one time or another been blamed, shamed, judged and otherwise harmed by mistaken beliefs which suggest their illness is faked, due to personality flaws, caused by weakness, laziness, lack of willpower or seeking attention, or for some other equally inaccurate reason. These views don’t believe or listen to what people are saying about their very real experiences of debilitating illness. They are deeply wounding – and importantly, they don’t reflect the research.

As a result of all these common misperceptions, I emphasize the fact and the scientific evidence explaining that ME/CFS is NOT PSYCHOLOGICAL throughout this post. This includes a quote from Dr. Robert Naviaux who states this very clearly.

The following sections present some of the physiological underpinnings that drive ME/CFS. They also explain how and why the belief that it is psychological is both false and out of date.

ME/CFS: The Cause Remains Unknown

ME/CFS is a disease of extreme fatigue affecting an estimated 1-2.5 million people in the U.S. (and many more undiagnosed) that involves multiple organ systems, often results in profound disability, and has no unifying understanding of cause nor treatment.

Because there is still no clear, universal diagnostic test, many physicians and other health care professionals still believe this illness is psychological.

Naviaux’s study provides detailed, objective, metabolic findings that disprove this perspective and offer an explanation for underlying drivers of ME/CFS as well as other chronic diseases.

In addition to fatigue, characteristic symptoms of ME/CFS include :

- worsening of fatigue and other symptoms with mental or physical activity

- difficulty recovering with rest

- symptoms that are not the result of excessive exertion (even if they are worsened by it)

- problems with memory and thinking (cognitive dysfunction often referred to as brain fog)

- sleep disturbance

- worsening with standing or sitting (orthostatic intolerance)

- chronic or intermittent pain in joints, muscles; headaches

- interstitial cystitis

- irritable bowel syndrome

- subnormal body temperatures and cold extremities, intolerance of extremes of hot or cold

- sensitivities to foods, odors, chemicals, or noise

- and more (see IOM/CDC diagnostic criteria, Canadian Consensus criteria).

Abnormalities exist in the autonomic nervous system and immune and other organ systems. These include (see also Naviaux, 2016; wikipedia):

- cerebral cytokine dysregulation

- natural killer cell dysfunction

- microbiome abnormalities

- abnormalities in metabolism and metabolites (Naviaux, 2016)

- widespread inflammation in the brain (Younger)

- increased lactate in the brain (lactate occurs with anaerobic metabolism) (Younger)

- reduced brain blood flow and brain volume, small brain lesions

- Th1/Th2 Imbalance (see more here and here)

- a subset of people with ME/CFS have slightly low cortisol levels

- and more.

ME/CFS Is Not Psychological

The perspective that ME/CFS is psychological is false and out of date

Many people with ME/CFS have been or are still told their illness is “all in their heads, ”is caused by mental health conditions such as depression”, or that it is “faked,” due to malingering or attempts to get attention, caused by depression, a personality flaw or unhelpful beliefs, and more. Findings such as those delineated above, new studies in epigenetics and other fields of study, and metabolic abnormalities identified by Dr. Naviaux in the study presented here, explain how this perspective is inaccurate and out of date.

Graded Exercise (GET) & Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) are not appropriate treatments

Following a single, highly flawed and discredited study called the PACE trial, graded exercise (GET), pacing, and cognitive behavioral therapies (CBT) became the single dominant treatment recommendations for ME/CFS by the medical profession and the Centers for Disease Control, among many others.

While these approaches can be supportive in the management of life with any chronic illness, exercise is a characteristic trigger of flares and worsening of fatigue and other symptoms of ME/CFS. Together with CBT, graded exercise inaccurately suggests the underlying causes of ME/CFS and other diseases are psychological, psychosomatic or “functional.” These recommendations elicit an appropriate response of concern, anger, disbelief and distrust by people with ME/CFS, and rightly so.

Polyvagal theory, Naviaux’s findings and trauma theory present a very different understanding and recommendations for ME/CFS, and further clarify how this disease is not psychological.

Naviaux’s Study: Shattering the Myth That ME/CFS is Psychological

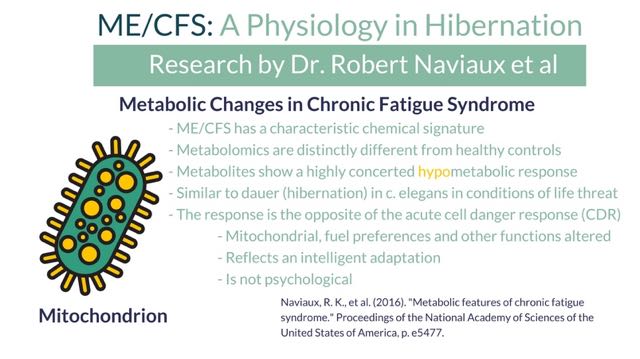

In 2016, Robert Naviaux, M.D, Ph.D, Professor of Medicine, Pediatrics and Pathology and director of the Mitochondrial and Metabolic Disease Center at UC San Diego and his team rocked the ME/CFS world when they identified 20 metabolic pathways in people with ME/CFS that were markedly different from healthy controls (here’s his slide show).

In their study, Metabolic features of chronic fatigue syndrome, Naviaux explained how these biological pathways reflected the activation of the cellular defense response (CDR). The CDR constitutes the survival response of a healthy organism to threats such as infection, lack of food or oxygen, or cold and other dangers (Naviaux, 2016):

“The cell danger response (CDR) is the evolutionarily conserved metabolic response that protects cells and hosts from harm. It is triggered by encounters with chemical, physical, or biological threats that exceed the cellular capacity for homeostasis.” (Naviaux, 2014).

80% of the abnormal metabolites Naviaux found in ME/CFS were part of the CDR pathway.

Intriguingly, they were in the opposite direction to the usual CDR response.

In the study, summarized here by Cort, Naviaux explained how these metabolites in ME/CFS were similar to those found in the very low metabolic state of hibernation.

- Naviaux explains the particular state of “dauer” identified in the ME/CFS study is not exactly the same as hibernation because “hibernation does not happen in humans.” I use the concepts of hibernation and freeze here for 4 reasons: 1) they are similar and more recognizable terms compared to the word “dauer”; 2) polyvagal theory describes these hypometabolic states in similar ways that serve similar functions of survival; 3) Naviaux references Porges’s work and the nervous system functions in describing the CDR; and 4) I haven’t found any definitions in the study or elsewhere about significant differences between these states.

The metabolites of hibernation are well known from studies of c. elegans, a worm that adapts to life-threatening situations such as insufficient food or oxygen, drought, and other environmental stressors that cannot be overcome by mobilizing, by entering a death-like state called “dauer.”

Dauer, like hibernation, is a means of preserving survival by severely curtailing functions of ordinary life such as energy, digestion and movement (Naviaux, 2016, p. e5477).

Naviaux added that:

“Similar to dauer, CFS appears to represent a hypometabolic survival state that is triggered by environmental stress.”

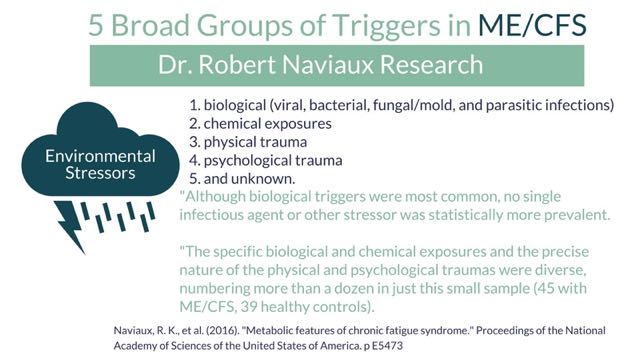

The study found that triggering events for ME/CFS fell broadly into five groups (p. e5473):

- biological (viral, bacterial, fungal/mold, and parasitic infections)

- chemical exposures

- physical trauma

- psychological trauma

- unknown.

“The specific biological and chemical exposures and the precise nature of the physical and psychological traumas were diverse, numbering more than a dozen in just this small sample. Several patients had multiple triggers that converged in the same year.

Although biological triggers were most common, no single infectious agent or other stressor was statistically more prevalent, and comprehensive testing for biological exposures in the control group was beyond the scope of this study”. (2016, p. e5473)

Naviaux further explains that ME/CFS is not directly caused by these triggers, not even by toxins or infections as common as Epstein-Barr virus or Lyme. Rather, when a body is exposed to these triggers and goes on to develop ME/CFS, it is due to an activation of the cell danger response.

These different environmental stressors, in other words, trigger a similar hibernation / freeze cell danger response in people who go on to develop ME/CFS. Just like they do in c. elegans.

Only a small percent of people who are acutely infected with Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) or human herpes virus 6 (HHV6), or Lyme disease go on to develop chronic symptoms. If the CDR remains chronically active, many kinds of chronic complex disease can occur.

In the case of CFS, when the CDR gets stuck, or is unable to overcome a danger, a second step kicks in [after the body has worked to fight off the infection and you have maybe been sick for days, weeks or months] that involves a kind of siege metabolism that further diverts resources away from mitochondria and sequesters or jettisons key metabolites and cofactors to make them unavailable to an invading pathogen, or acts to sequester toxins in specialized cells and tissues to limit systemic exposure. This has the effect of further consolidating the hypometabolic state (2016, FAQ).

Naviaux is saying that the effects of these infections and toxins are real but that they lead to ME/CFS because they trigger a particular pattern of the cell danger response.

Importantly, despite the heterogeneity of triggers, the cellular response to these environmental stressors in patients who developed CFS was homogeneous and statistically robust.

That supported the notion that it is the unified cellular response, and not the specific trigger, that lies at the root of the metabolic features of CFS (2016, p. e5473).

So while your body may have been affected by an infection or exposure to a toxin such as mold, your illness arose because of the CDR and all it entails (which includes potentially having difficulty getting rid of the infection or toxin.)

As Naviaux described in their Q&A document, this is not because ME/CFS is psychological (2016):

Q1. Some people still argue that CFS is not a real illness but all in the mind. Does your discovery of a chemical signature help shatter this myth?’

“Yes. The chemical signature that we discovered is evidence that CFS is an objective metabolic disorder that affects mitochondrial energy metabolism, immune function, GI function, the microbiome, the autonomic nervous system, neuroendocrine, and other brain functions. These 7 systems are all connected in a network that is in constant communication. While it is true that you cannot change one of these 7 systems without producing compensatory changes in the others, it is the language of chemistry and metabolism that interconnects them all [read more].

Q1.1. If you found that CFS is caused by chemical changes, why do you ask about childhood trauma in your new questionnaire for the expanded CFS metabolomics study? The questions made me think you were just like all the other doctors who told me that CFS was all in my head?

“The answer to this question has several layers. Perhaps the most important is founded on our discovery that the brain controls metabolism. Any factor that causes a chronic change in how the brain works will produce objective chemical changes in the blood [read more].

Here are insights into why people with ME/CFS can experience states of hibernation, it is possible to have gotten to a state that feels death-like, and why it can be so very difficult to recover.

You’ll learn about science that supports and expands on Naviaux’s findings of the deep, very real physiological basis for prolonged states of metabolic hibernation. Plus, I’ll add more context to explain why ME/CFS is no more psychological, or all in our heads than the state of dauer is for c. elegans or states of hibernation are in bears.

I incorporate areas of study Naviaux refers to in his articles, which include brain development, neurobiology, and epigenetics. I also reference the science of traumatic stress, which offers especially pertinent insights into the effects of environmental stressors such as infections, toxins, as well as adversity on long-term health, including risk for states of hibernation; and how these effects are intelligent, biological, epigenetic and not about simple stress.

The science of traumatic stress, neurobiology, epigenetics and more demonstrate that subtle and overt types of trauma and adversity directly alter physiology, cell function, metabolism, immune and nervous system function and other organic and biological activities to increase risk for autoimmune and other chronic physical diseases, among many other effects.

They indicate that psychological symptoms are a separate symptom of trauma and not the cause of ME/CFS nor of these other effects (Ridout, 2018).

To restate this important distinction, the effects of trauma are not psychological in origin – even if they include concurrent psychological symptoms. Science that has largely been overlooked in medicine offers insights that help explain why the cell danger response can produce a more or less permanent state of hypometabolism and cause ME/CFS in some people.

I was never introduced to this science as a doctor but it has helped me gain a new understanding and respect for autonomic nervous system function and made sense of my ME/CFS (as well as autoimmune diseases such as type 1 diabetes, MS, RA and other illnesses).

Here’s what is being learned about how human bodies orient and respond to threat and how this can set individuals up with pathways leading to states of dauer, hibernation, and freeze.

It starts with the autonomic nervous system and how its main goal is to maximize survival – even when the cost is high.

This research is very slowly beginning to change the face of health care, even as it has a long way yet to go (National Research Council and Institute of Medicine, 2000; Shonkoff, 2012; Chitty, 2013).

Autonomic Nervous System Survival Strategies

As Naviaux explains, the cell danger response is not a new concept.

“The concept of the cell danger response … has evolved from a confluence of six rivers of scholarship that have developed in relative isolation over the past 60 years (2014, p.8).

Furthermore, the CDR is regulated by our autonomic nervous systems:

“The systemic form of the CDR, and its magnified form, the purinergic life-threat response (PLTR), are under direct control by ancient pathways in the brain that are ultimately coordinated by centers in the brainstem (2014, p. 8).

While individual cells and tissues can mount their own defensive responses to infection, physical wounds (such as surgery or physical trauma), toxins and other threats, the nervous system gets involved when the cell defense response becomes stuck and affects the whole body, such as in ME/CFS.

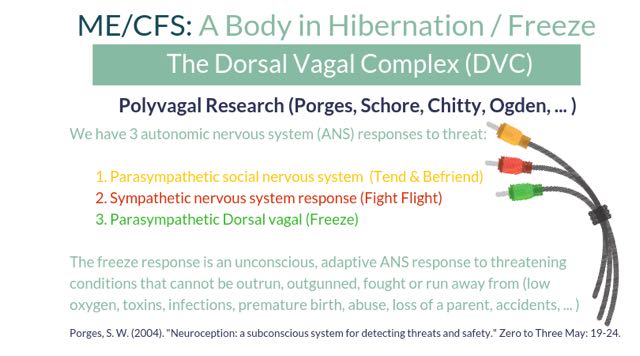

Our autonomic nervous system (ANS) manages and regulates physiological functions such as blood pressure, heart rate, temperature, immune activity, digestion, mitochondrial function, energy levels, metabolism and more. It supports these functions by directing cellular, metabolic and other underlying processes that involve many organ systems.

One of the branches of the autonomic nervous system (ANS) that can cause hibernation-like states in humans originates in the brainstem which is where the CDR is regulated.

It is one of three branches of autonomic nervous system, all of which interact with one another to influence short and long-term health. Below is an overview of the three branches, starting with fight and flight of the sympathetic nervous system – an important aspect of Naviaux’s CDR.

Naviaux writes about these three branches of the nervous system, which are described below, and how the CDR is the source of over 100 diseases identified so far, including ME/CFS, POTS, Fibromyalgia, MS, RA, Inflammatory Bowel Disease, Sjogren’s, diabetes and more). The italics are mine for clarification (Naviaux, 2018, p. 11):

When the CDR is chronically activated, the coordination between the two limbs of the vagus nerve [VVC and DVC] is disrupted. This results in disinhibiting the sympathetic nervous system [i.e.: no longer inhibiting fight flight reactions] and the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA), which dominate during illness.

(The following references support the sections below on the autonomic nervous system and polyvagal theory, including Chitty: Chapter 6, (2013); Fredrickson (2013); Levine, 2010, Chapter 4; Ogden, Chapter 5, (2006); Porges (1992, 1995, 2001, 2004, 2009); Schore (1994, 2001).)

Sympathetic Nervous System (SNS) Fight / Flight

We are most familiar with the sympathetic branch of the autonomic nervous system, which is the branch that can make us feel like someone’s put a foot on our gas pedal. The sympathetic nervous system enables us to take action in everyday life, and also in the event of threat. When we’re in danger, it helps us fight, chase off predators, or flee a hurricane.

In the first minutes and hours of a fight or flight response to stress, our bodies release adrenaline, increase our blood pressure and heart rate, augment our body temperature and breathing, enhance our blood sugar availability to fuel our muscles for fighting and fleeing, and increase our immune response (Dhabhar, 2018). This is all aimed at maximizing energy levels to support fight or flight.

And it is all part of the healthy cell danger response.

These changes optimize our ability to survive through escape mechanisms and by warding off infections, healing wounds by clotting more efficiently, and increasing our speed and strength.

“[The CDR is a] coordinated set of cellular responses … that evolved to help the cell defend itself from microbial attack or physical harm … and at its most fundamental and most ancient role: to improve cell and host survival after viral attack (Naviaux 2014, p. 7).

The actions of the acute fight or flight response are consistent with Naviaux’s acute cell danger response, which is the opposite of what he found in ME/CFS (paraphrased from his 2016 article on ME/CFS):

The acute CDR is found in acute infection, during acute inflammation and in the metabolic syndrome (a cluster of conditions that include high blood pressure, high cholesterol, insulin resistance and high blood sugar levels, and increased fat around the waist area. These symptoms, also known as Syndrome X, are associated with increased risk for heart disease, stroke and diabetes).

In this acute sympathetic nervous system response, our bodies also decrease or suppress functions that aren’t important for immediate survival, such as digestion and rest.

If stress continues for a long time, an increased degree of fight or flight arises in which cortisol is released, the immune system is suppressed, inflammation rises and symptoms can occur.

In health, our bodies return to baseline when the stressor goes away or the threat disappears.

In health, at rest, and in play and safety, the sympathetic nervous system coordinates with the other branches of the autonomic nervous system to constantly tweak and maintain just the right levels of blood pressure, heart rate, oxygen consumption, mitochondrial function and other basics that support our ever changing activities of daily life.

In some circumstances, which I’ll discuss later, the sympathetic nervous system remains turned “on” and this acute CDR contributes to disease (Naviaux, 2014).

The Social Nervous System (“The Vagus”)

As introduced in an earlier post by Tim Vaughan here on Health Rising, psychophysiologist Stephen Porges’ polyvagal theory indicates that the parasympathetic portion of the autonomic nervous system is comprised of two branches rather than one.

The more evolved branch of the parasympathetic nervous system is present in mammals and is called the social nervous system or the ventral vagus complex (VVC).

The social nervous system is regulated by a parasympathetic nervous system branch called the ventral vagus complex because it originates in the brainstem (in the nucleus ambiguous on the ventral or belly-like surface of the brain). Also known as Cranial Nerve X (Ten), the ventral vagus travels from the brain to the facial muscles down to the gut. It is the faster of the two branches and supports safety and survival in the most metabolically energy-efficient capacities we have: those of connection and communication.

If you’ve heard of the ventral vagus, it’s because it is “The Vagus” we refer to when we incorporate mind body practices such as yoga nidra, mindfulness, or meditation to protect or improve our health; use vagal stimulation as a treatment tool; or take up a hobby or go on a vacation to slow down and catch our breath. You may also have heard of it because this is the branch that facilitates the survival response of “tend and befriend” (Taylor, 2000).

In health, our social nervous systems are in charge of autonomic nervous system functions and can inhibit fight or flight as well as institute a process called freeze.

A healthy ventral vagus allows us to connect to ourselves and the world, and to empathize and bond with others, which supports safety through numbers and strength. It also enables people to read others’ facial expressions to assess whether they are safe to approach or should be avoided. This is all part of a highly evolved and built-in survival mechanism.

The ventral vagus allows us to sense into our gut feelings that warn us of safety vs danger, and to communicate using energy-sparing actions through our voices, gestures and facial muscles that show and express our feelings and boundaries.

Through the ventral vagus, for example, babies draw their parents towards them with their big, curious, beautiful eyes, their smiles, and their cries of hunger or discomfort. In health, babies pull at our heart strings to elicit bonds of love and the desire to nurture and protect them. This is all facilitated by the ventral vagus, which stimulates behaviors (cooing, smiling, eye contact), hormones (oxytocin and vasopressin), feelings (love, comfort, pleasure) and more that support feelings of love in both babies and their parents.

This is important because human babies and mammals are born at a very immature stage of development, when it is critical for survival to draw in the proximity and care of adults.

Children and adults communicate affection and form protective, supportive alliances through touch, a smile or a conversation. These are actions of the ventral vagus. The social nervous system also supports our defenses with verbal boundaries like “no” or gestures, such as hand signals inviting approach or conveying “stop.”

The social nervous system facilitates all of these functions through the nerves that connect to our eyes, ears, mouths and facial muscles, to our hearts and voices, and through our endocrine, immune and other organ systems.

The ventral vagus makes survival and defense actions possible by placing a gentle brake on our baseline heart rates, which helps us feel more connected and relaxed. This occurs at the cellular and physiological levels and can often be enhanced through mind body practices.

Defenses that use words, eye contact and gestures are energy efficient.

Babies avert their gaze and look away when they are getting too much input, signaling the communicator to stop or slow down. When you talk someone down from raging at or firing you rather than fleeing the office, you are engaging your ventral vagus. The same is true when you stay present and engaged in the middle of a heated or painful argument with a spouse rather than attacking them physically, or disappearing (which would be sympathetic nervous system functions of fight and flight). Our ventral vagus also enables us to use the tone of our voices, such as to soothe a baby who is distressed or calm down a scared animal so that it doesn’t attack. And you may signal “stop” to a stranger who is approaching closer or faster than you are comfortable with before deciding if you need to flee.

This is the way of the social nervous system.

In health, the ventral vagus gently suppresses fight and flight unless it’s truly needed.

In health, our ventral vagus subtly immobilizes us so we can hold still long enough to make love, bond, or snuggle with and care for our babies and children – which is how the most vulnerable among us engage protection through connection.

In health, the ventral vagus can release its gentle brake so our heart rates can rise a little for activities such as standing, walking and playing. This enables us to shift gears without resorting to the higher energy functions of SNS fight and flight systems with releases of adrenaline or cortisol.

The ventral vagus, then, is a critical player in keeping us healthy through energy-efficient means.

When ventral vagus functions get interrupted, however, we can end up in states of prolonged fight and flight, hibernation and freeze, or some combination of both.

This is what happens when we have an illness like ME/CFS and feel as though we have one foot on the gas and one foot on the brake. It means that we each have our own, unique, individual version of the same disease. I’ll discuss this a little more after the next section on the freeze response.

The Parasympathetic Nervous System (PNS) Freeze / Hibernation

If you’ve ever fainted at the sight of blood or of a needle (Bracha, 2004), felt rooted to the ground and unable to move during or after a stressful or scary event (hearing a loud, unexpected sound; seeing something horrifying; having just survived a car accident), you’ve experienced a moment of physiological hibernation or “freeze.”

As you know, it was not something you did on purpose, through conscious control, or to “get attention.”

This “freeze” state is facilitated by the branch of the PNS that acts as a brake in an even stronger manner than the ventral vagus.

Going into states of freeze occurs when our other two forms of self protection – fight or flight and tend and befriend – described above, are either unsuccessful or unlikely to succeed.

Like c. elegans and other living creatures, shutting down (freezing) and going into hibernation is a CDR pathway designed to maximize survival when fighting, fleeing and connecting are not available options.

As Naviaux asserts in his 2016 article, the state of freeze:

is an evolutionarily conserved, genetically regulated, hypometabolic state similar to dauer that permits survival and persistence under conditions of environmental stress but at the cost of severely curtailed function and quality of life (2016, p. e5477).

In other words, the option to freeze has persisted in life forms of all kinds as an evolutionary adaptation to maximize survival.

As mentioned in this video of an opossum in freeze, states of freeze are neither psychological nor manufactured.

In states of freeze, our bodies use the same physiology and produce the same metabolites that c. elegans does when it goes into hibernation to wait out a threat it cannot successfully outrun or outgun.

States of freeze and hibernation are facilitated by the second branch of the parasympathetic nervous system, the dorsal vagal complex (DVC), which, like the ventral vagus, originates in the brainstem (Porges, Chitty).

The Dorsal Vagal Complex (DVC)

In health, the dorsal vagus interacts with the other branches of the autonomic nervous system and uses its braking function to gently decrease blood pressure, heart rate, oxygen use, and to support digestion so that we are operating at maximum efficiency. It’s similar to a thermostat that turns an air conditioner on and off to maintain a comfortable temperature rather than perpetually staying on and making it too cold.

In health, the dorsal vagus coordinates its functions with the social nervous system branch and the sympathetic nervous system to support changes in activity levels that takes us from activity to rest, eating to digesting, and back.

In health, the dorsal vagus functions to help us feel calm and available for play and work and rest.

Under threat, the dorsal vagus intensifies its brake.

Even more than fight and flight, the state of freeze is not a conscious choice or a psychological ploy. It is an unconscious autonomic nervous system response of last resort used only in circumstances we are relatively helpless to address and towards threats that cannot be overcome.

In freeze, the opossum’s heart rate, blood pressure and body temperature actually go down (Gabrielsen, 1985).

These aspects of the freeze state are what the opossum and many other creatures have evolved as a primary defense strategy to fool predators into thinking they are already dead. Predators are less likely to attack when prey is unmoving and already looks dead.

In freeze, our own blood pressure, heart rate, temperature and oxygen levels can also go down.

We may feel slow or foggy headed; we may disconnect and watch the event unfold as if we’re standing outside of our bodies; or we may feel numb, limp or unable to move.

We may also feel exhausted or too weak to stand.

Freeze states can also flood a body with feel-good hormones and numbness or even euphoria. This is nature’s way of supporting humans (and other animals) so that the pain of a broken bone or a physical assault do not prevent trying to escape and engaging fight and flight if an opportunity arises.

When humans experience states of freeze, our physiology uses the same CDR pathways as opossums and bears and c. elegans.

In freeze / hibernation, our bodies divert energy from eating and digesting to hunkering down and conserving as many resources as possible.

Just like c. elegans.

As in c. elegans, the dorsal vagal complex takes humans into states of freeze when other options for survival in the face of threat aren’t available. Our bodies can also go “dorsal vagal” if we’ve had experiences of being unsuccessful at surviving or escaping using fight, flight or ventral vagal functions in the past.

Naviaux explains that dauer / freeze / hibernation physiology occurs as an intelligent strategy, not as a random mistake, mutation or a problem with faulty hardware or software:

- Entry into dauer confers a survival advantage in harsh conditions.

- Entering a hypometabolic state during times of environmental threat is adaptive, even though it comes at the cost of decreasing the optimal functional capacity.

- When the dauer response is blocked by certain mutations, animals are short-lived when exposed to environmental stress (p e5477).

In other words, when the freeze response is not an option, we don’t live as long. The definition of Dauer, interestingly, means “persistence or long-lived in German” (Naviaux, 2016, p. e5477).

As Naviaux further explains, living in states of relative freeze for prolonged periods comes with a recognizable set of physiological changes.

Dauer is comprised of an evolutionarily conserved and synergistic suite of metabolic and structural changes.

This state makes it possible to live efficiently by altering a number of basic mitochondrial functions, fuel preferences, behavior, and physical features.

Changes linked with hypometabolism run in the opposite direction of the acute CDR (Naviaux, 2016), which, as mentioned earlier, is consistent with sympathetic states of fight and flight.

The metabolites Naviaux identified in ME/CFS patients reflect a fundamental reset in our physiology (to use Cort’s term) that is consistent with freeze.

This dauer pathway, akin to freeze and hibernation and opposite to the acute CDR, includes the following:

- energy conservation and death-like states whose primary goal is survival despite the cost

- organism geared towards survival via inaction rather than action, to wait out overwhelming threat

- altered Th1/Th2 imbalance

- decreased immune system ability to fight infection

- loss of antibacterial and antifungal activity

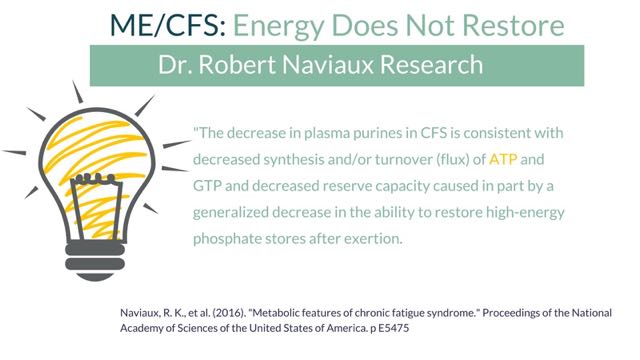

- a “decrease in the ability to restore high-energy phosphate stores after exertion” (this relates to mitochondrial ATP and energy production)

- normal or low blood pressure

- aversion to glucose as a fuel with preference for fat as a fuel (Naviaux, 2016; Lant, 2010) [this suggests why people with ME/CFS may do better with ketogenic diets that use fat as the primary fuel]

- loss of intestinal mucosal integrity and leaky gut

- decreased gut absorption as part of a hypometabolic survival response

- changes in DNA methylation and histone modification that alter gene expression (epigenetic changes, Naviaux, 2014. p. 10)

- stress-induced cholesterol pathways, which are different from routes used in health

- altered mitochondrial function and the finding that:

Mitochondria represent the front lines in cellular defense and innate immunity … Their rapid metabolism makes [them] “canaries in the coal mine” for the cell.” (Naviaux, 2014, p. 9-10).

Low cortisol is another shift that happens as part of nervous system response to threat. Low cortisol is common in late phases of PTSD and in adults with a history of adversity in childhood as well as in their parents’ lives. Cortisol is measured in our physiology, so like other physiological effects of environmental stressors including psychological trauma and adversity, it is not a psychological effect but a biological effect.

Low cortisol is seen in many chronic diseases such as fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS), cardiovascular and gastrointestinal diseases, rheumatoid arthritis, psoriasis, and thyroid disease (Lehrner, 2016, p. 268). Low levels of cortisol are not caused by adrenal exhaustion but occur after a body responds to a prolonged threat and becomes more sensitive to this particular chemical.

To reiterate, just like Naviaux’s findings, this physiological response is not a psychological effect of trauma but one that is driven by changes in the nervous system and linked to the nervous system’s perception of threat.

Naviaux explains that the cost of being in a prolonged state of freeze, hibernation or dauer expresses itself as symptoms.

The changes in function listed above translate to many well-known characteristics of this disease.

The dorsal vagal survival state:

- reduces energy levels to death-like states

- inhibits mobilization at cellular, mitochondrial, and other physiological levels

- conserves energy by suppressing states of fight and flight.

Freeze states in humans also inhibit the social nervous system.

Low blood pressure, exhaustion, and other altered physiological processes are all NORMAL aspects and functions of the state of freeze. They are aimed at reducing the body’s energy consumption in order to preserve life as long as possible while we outwait the threat.

So what Naviaux is saying, and what research in the cell danger response and into polyvagal theory and hypometabolic states is finding, is that while the aforementioned signs and symptoms that can occur in a chronic illness like ME/CFS are all entirely real, these are not the CAUSE of ME/CFS.

In other words, a hypometabolic cell danger response is an intelligent, physiological, biological, chemical and epigenetic process that has gotten prolonged.

It is a state that has gone from a single location, group of cells, or tissue alarm to a system-wide state of defense that is guided and directed by the nervous system.

As a result, ME/CFS, like type 1 diabetes, POTS, fibromyalgia, celiac disease, MS, lupus, asthma, Parkinson’s, autism, Alzheimer’s and 100 other diseases that Naviaux refers to, reflects a nervous system pattern that is deliberately inciting one or more kinds of cell danger responses and all the changes they entail.

ME/CFS is, therefore:

- not caused by adrenal exhaustion even if adrenal function is low. (Low adrenal function supports states of freeze while high function is supportive of fight/flight; both or alternating functions can be seen in ME/CFS)

- not due to a thyroid that is out of whack even if our thyroid activity is low. (Low or high thyroid activity supports states of freeze and low energy or fight / flight for survival)

- not primarily from a lack of Vitamin D, nutrients or building blocks that enable mitochondria to function well even though these states can cause symptoms. (We may have low building blocks because of poor absorption but many, such as Vitamin D, are kept intentionally low because the body is more or less sensitive to them in states of freeze, is conserving energy by not producing chemicals that are not absolutely necessary for survival, or is actively removing molecules and chemicals in order to create and preserve a freeze state that needs these factors to be low or absent for optimum function and self-protection) [Naviaux, 2014]

- not directly the result of leaky gut. (Cell walls in the body and gut are intentionally more permeable during states of dauer / freeze / hibernation)

- and so on.

The question in ME/CFS thus become: how do humans get stuck in a state of ME/CFS and freeze – especially if there’s no obvious threat in the present or at the time of onset?

This is where the science of traumatic stress offers important clues. The following draws from research findings that most health care professionals and medical care have not yet caught up with. They include the finding that ME/CFS and freeze often present in it are effects of environmental stressors; i.e. neither is psychological.

Individual Expressions of Freeze and CDRs (“Tired” vs “Wired and Tired”)

There are many different versions of freeze including combinations in which “freeze” can be the dominant problem manifesting as disease and other symptoms.

Tired or more “Pure Dorsal Vagal”

Some types of freeze produce the ‘collapsy”, death-like, shock-like states that Dr. Peter Levine refers to as “fold,”( p. 49) and that others describe as “faint,” along with many other terms such as shock and other terms. These states are characterized by feeling tired / exhausted / death-like , having low body temperature, low blood pressure, etc., and are a more “pure” form of just the hypometabolic CDR or dorsal vagal state. There are additional variations of freeze I don’t go into here.

Some people with ME/CFS are more purely dorsal vagal.

In addition to the physiologic / immune / gut and metabolic abnormalities mentioned elsewhere, the dorsal vagal state can show up in behaviors, emotions, relationships, dreams as well as in other ways. This is, to be clear, not because it is psychological but because the effects of environmental stressors on nervous system function influence all types of health.

As one example, I had dreams of being completely immobilized for many decades. These night terrors started in childhood long before the onset of my ME/CFS. I would awaken within the dream, thinking it was real, and feel terrified but unable to move, cry out, or wake myself up (dorsal vagal state). I had this dream regularly well into adulthood and it only gradually began to change as I began to heal nervous system perceptions of threat. My sleep paralysis states started to shift in parallel with improvements in my ME/CFS.

Early on in these dreams, I started being able to wake myself up with some effort. Over time, while still in the dream, I was able to sometimes make a sound (social nervous system) and eventually to begin to move. At first, these movements were slow, rubbery and without strength (still a dorsal vagal response).

Eventually I was able to mobilize and run in some dreams. In others I was actually able to strike the attacker in a solid, strong, effective way (sympathetic fight / flight). It’s been a long time now since I’ve had any versions of this dream and my ME/CFS is doing much better as well.

Wired and Tired: A Combination of Freeze and Underlying Fight/Flight

Other people experience a combination of both fight / flight AND freeze, in which freeze is the dominant and most visible form and set of symptoms, but suppresses an underlying state of heightened fight /flight.

This makes some people with ME/CFS feel both wired AND tired at the same time.

If you have ME/CFS and also have high blood pressure, the metabolic syndrome with insulin resistance or high cholesterol, or are overweight etc. or if you tend to feel more “wired and tired” than “tired,” this is consistent with a freeze state that dominates over a state of overactive fight/flight.

This is an example of a system that has components of both types of CDRs: both the hypometabolic and the acute CDR sympathetic nervous system response.

This is what is seen in the gazelle that suddenly shifts from running at full tilt (sympathetic flight) and collapsing just before the cheetah pounces on her (dorsal vagal fold).

Her body shifts into parasympathetic mode when her nervous system perceives that she cannot survive the chase by running. Her nervous system tells her body to shut down, she collapses and immobilizes, and this provides a numbness and disconnection that make death painless, even if she gets munched.

Underneath this immobility, however, her body is primed to go from 0 to 60 in a moment’s notice should the cheetah get distracted long enough for her to escape (you see an example of this shift out of immobility to escape in this video of the gazelle).

Naviaux does not talk about this combination of CDRs in his 2016 article but does refer to 3 different types of disease states based on which type of CDR and which stage of healing the body is in (2018). Such mixed states are well known in the trauma literature.

Oscillating Between Freeze and Flight/Flight

While some PWME (people with ME/CFS) have symptoms that are predominantly purely dorsal vagal or dorsal vagal combined with fight or flight, some oscillate between various combinations of fight or flight, and freeze / faint / fold. This has been shown in PTSD, where a person can be in a state of fight or flight (hypervigilance, high blood pressure, states of high blood clotting factors, or rage) in one moment, and in a state of exhaustion, collapse, immobilization, low blood pressure, cold body temperature or depression, in the next.

Science is showing that such variations in symptoms are an effect of environmental stress and the resulting perceptions of threat in the nervous system which are not psychological in nature. In other words, nervous system changes towards hibernation and freeze as well as fight/flight are just as real in humans with ME/CFS and other chronic diseases as they are in c. elegans and other animals.

To offer another example, I have long had a predominantly dorsal vagal imprint in my own ME/CFS that corresponds to a history of low blood pressure (varying between about 90/60 to 100/70). As I recover, my blood pressure has very gradually increased to within more common ranges (It was 118/76 at my annual exam in September – the highest it’s been in the 20 years since the onset of my ME/CFS). I have also experienced more and more irritability as my health has improved – suggesting the emergence of an underlying state of fight/flight.

Another impulse seen in the ME/CFS community is a profound impulse to escape to some quiet place. I had such an impulse when I practiced medicine and life was too full, hectic and overwhelming. The craving arose around the onset of my first fatigue attacks 20 years ago. I fantasized about finding a job in the middle of a national park somewhere, monitoring for forest fires and holing up in a tiny tower high up on stilts, away from everyone and everything except the quiet of nature.

The desire to escape has components of flight but more likely derives from a dorsal vagal freeze response that craves an environment of quiet, stillness and the avoidance of social contact to support the process of healing (see Levine, 2010, Chapter 4)

Why Exhaustion and Other Symptoms Persist in ME/CFS

In the case of ME/CFS, our brains may insist on remaining in a state of hibernation until our autonomic nervous system gets the message that the threat is gone and that it’s safe return to the responsive, moment-to-moment dance that reflects ongoing fluctuating, adaptive interactions and balance between all three branches of the nervous system.

Naviaux explains that while a serious disease like ME/CFS may begin after an environmental stressor such as an infection, a vaccine or a stressful or psychologically traumatic event, the trigger is simply the final straw in a series of life long exposures rather than the single or actual cause of the disease.

As Naviaux reiterates, the symptoms of ME/CFS are not indications of broken mitochondria, faulty genes or nutrient deficiencies so much as they represent the effects of an organism hell bent on maintaining low energy states of hibernation and freeze in all available ways (cell function, physiology, behavior, emotions and more).

In my next post, I’ll build on Naviaux’s work to describe what we now understand about how exposures and life experiences – infection, toxins, loss of a parent in childhood, abuse, a difficult birth, a vaccine – can lead to ME/CFS in some of us, and not in others. I’ll describe research that sheds light on why the stressor that triggers onset of ME/CFS can seem completely minor or not even threatening, and why flares can occur with similarly negligible stressors.

For more, here’s my story with ME/CFS and how this lens makes sense of my symptoms and is helping me to heal. Here’s a detailed summary of the nervous system in chronic illness that is also an overview of my blog. I have additional free downloadables on this page.

Check out Veronique’s first article on this subject.

References

Alonzo, A. A. (2000). “The experience of chronic illness and post-traumatic stress disorder: the consequences of cumulative adversity.” Soc Sci Med 50(10): 1475-1484.

Calkins, K. and S. U. Devaskar (2011). “Fetal origins of adult disease.” Curr Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care 41(6): 158-176.

Chitty, J. (2013). Dancing with Yin and Yang. Boulder, Polarity Press.

Dhabhar, F. S. (2009). “Enhancing versus suppressive effects of stress on immune function: implications for immunoprotection and immunopathology.” Neuroimmunomodulation 16(5): 300-317.

Dhabhar, F. S. (2018). “The short-term stress response – Mother nature’s mechanism for enhancing protection and performance under conditions of threat, challenge, and opportunity.” Front Neuroendocrinol 49: 175-192.

Dube, S. R., D. Fairweather, W. S. Pearson, V. J. Felitti, R. F. Anda and J. B. Croft (2009). “Cumulative Childhood Stress and Autoimmune Diseases in Adults.” Psychosom Med 71(2): 243-250.

Felitti, V. J., R. F. Anda, D. Nordenberg, D. F. Williamson, A. M. Spitz, V. Edwards, M. P. Koss and J. S. Marks (1998). “Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults. The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study [see comments].” Am J Prev Med 14(4): 245-258.

Fredrickson, B. (2013). Love 2.0: Finding Happiness and Health in Moments of Connection, Plume.

Gabrielsen, G. W. and E. N. Smith (1985). “Physiological responses associated with feigned death in the American opossum.” Acta Physiol Scand 123(4): 393-398.

Hofer, M. A. (1994). “Early relationships as regulators of infant physiology and behavior.” Acta Paediatr Suppl 397: 9-18.

Hughes, K., M. A. Bellis, K. A. Hardcastle, D. Sethi, A. Butchart, C. Mikton, L. Jones and M. P. Dunne (2017). “The effect of multiple adverse childhood experiences on health: a systematic review and meta-analysis.” Lancet Public Health 2(8): e356-e366.

Jackson Nakazawa, D. (2015). Childhood Disrupted: How Your Biography Becomes Your Biology, and How You Can Heal. New York City, Atria Books.

Klaus, M. H. and J. H. Kennell (1976). Maternal-infant bonding. St. Louis, Mosby.

Lant, B. and K. B. Storey (2010). “An overview of stress response and hypometabolic strategies in Caenorhabditis elegans: conserved and contrasting signals with the mammalian system.” International Journal of Biological Sciences 6(1): 9-50.

Levine, P. A. (2010). In an Unspoken Voice: How the body releases trauma and restores goodness. Berkeley, North Atlantic.

Madrid, A. (2005). “Helping children with asthma by repairing maternal-infant bonding problems.” Am J Clin Hypn 48(3-4): 199-211.

Moore, S. R., L. M. McEwen, J. Quirt, A. Morin, S. M. Mah, R. G. Barr, W. T. Boyce and M. S. Kobor (2017). “Epigenetic correlates of neonatal contact in humans.” Dev Psychopathol 29(5): 1517-1538.

National Research Council and Institute of Medicine (2000). From Neurons to Neighborhoods: the science of early childhood development. Committee on integrating the science of early childhood development. Board on children, youth, and families, Commission on behavioral and social sciences and education. Washington, D.C., National Academy Press.

Naviaux, R. K. (2014). “Metabolic features of the cell danger response.” Mitochondrion 16: 7-17.

Naviaux, R. K., J. C. Naviaux, K. Li, A. T. Bright, W. A. Alaynick, L. Wang, A. Baxter, N. Nathan, W. Anderson and E. Gordon (2016). “Metabolic features of chronic fatigue syndrome.” Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A.

Naviaux, R. (2018 (epub ahead of print). “Metabolic features and regulation of the healing cycle—A new model for chronic disease pathogenesis and treatment.” Mitochondrian.

Ogden, P., K. Minton and C. Pain (2006). Trauma and the Body: A sensorimotor approach to psychotherapy. New York, Norton & Co.

Porges, S. W. (1992). “Vagal tone: a physiologic marker of stress vulnerability.” Pediatrics 90(3 Pt 2): 498-504.

Porges, S. W. (1995). “Orienting in a defensive world: mammalian modifications of our evolutionary heritage. A Polyvagal Theory.” Psychophysiology 32: 301-318.

Porges, S. W. (2001). “The polyvagal theory: phylogenetic substrates of a social nervous system.” Int J Psychophysiol 42(2): 123-146.

Porges, S. W. (2004). “Neuroception: a subconscious system for detecting threats and safety.” Zero to Three May: 19-24.

Porges, S. W. (2009). “The polyvagal theory: New insights into adaptive reactions of the autonomic nervous system.” Cleveland Clinic journal of medicine 76(Suppl 2): S86-S90.

Ridout, K. K., M. Khan and S. J. Ridout (2018). “Adverse Childhood Experiences Run Deep: Toxic Early Life Stress, Telomeres, and Mitochondrial DNA Copy Number, the Biological Markers of Cumulative Stress.” Bioessays: e1800077.

Romens, S. E., J. McDonald, J. Svaren and S. D. Pollak (2015). “Associations between early life stress and gene methylation in children.” Child Dev 86(1): 303-309.

Sandman, C. A. (2018). “Prenatal CRH: An integrating signal of fetal distress.” Dev Psychopathol30(3): 941-952.

Scaer, R. (2005). The Trauma Spectrum: Hidden wounds and human resiliency. New York, W.W. Norton.

Scaer, R. C. (2001). The Body Bears the Burden: Trauma, dissociation, and disease. New York, Haworth Medical.

Schore, A. N. (1994). Affect regulation and the origin of the self: the neurobiology of emotional development. Hillsdale, NJ, Lawrence Erlbaum.

Schore, A. N. (2001). “The effects of secure attachment relationship on right brain development, affect regulation, and infant mental health.” Infant Ment Health J 22: 7-66.

Shalev, I., T. E. Moffitt, K. Sugden, B. Williams, R. M. Houts, A. Danese, J. Mill, L. Arseneault and A. Caspi (2013). “Exposure to violence during childhood is associated with telomere erosion from 5 to 10 years of age: a longitudinal study.” Mol Psychiatry 18(5): 576-581.

Shonkoff, J. P., A. S. Garner, C. Committee on Psychosocial Aspects of, H. Family, A. Committee on Early Childhood, C. Dependent, D. Section on and P. Behavioral (2012). “The lifelong effects of early childhood adversity and toxic stress.” Pediatrics 129(1): e232-246.

Taylor, S. E., L. C. Klein, B. P. Lewis, Gruenewald, Tara L. , R. A. R. Gurung and J. A. Updegraff (2000). “Female responses to stress: Tend and befriend.” Psychological Review 107(3): 411-42

This article is so on point. I have suffered for over 35 years.

Thank you

Yikes excellent but long read I got bits of it only but I can so relate to the freeze state. I am so weak I have to force myself to breath and honestly feel like I’m about to cross to the other side. Scary but also feel extremely relaxed and dead at the same time

Yes it is a long read and I encourage printing it out.

What a difficult state Nat! Hang in there.

I think I encounter the freeze state frequently. For me it’s almost feels like some wires got crossed – which is why the foot on the gas pedal and brake so appeals to me. That exactly sums up how I feel sometimes. I want to move but the brake is on!

Yes. That wanting to move is still there in so many of us (and so strong some time it triggers tremendous frustration, to put it mildly), so much of the time but that brake is on. So well put Cort.

Hi Nat,

So sorry you’re in such an extreme place. I remember a period of time when I felt literally “death-like.” It was the word that arose, out of nowhere, to best fit how I felt. It wasn’t anything I could explain, but I was exhausted and felt heavy and somehow “awful” even when lying down and doing nothing. It’s quite intriguing that you also feel relaxed – something about that is intriguing. I wish you all the best.

Thanks Veronique! Luckily those episodes don’t last long!

I was diagnosed with ME/CFS about 10 years ago. Before I became sick I was a first generation college grad who graduated with honors and an overachiever. Although I thirst for knowledge and read a lot, I tend not to read a lot about ME because I find it is what it is. I scan everything for anything new, any new research findings or trials. This article is the first one that I printed out and am keeping. When I read it, I was deeply impacted. It’s the first time I felt I was reading about exactly what is happening to me. Thank you so much for your insight and this article.

I’m so glad to hear of it’s impact and that it resonates Christina – thanks for letting me know.

Hi Nat,

That resembles a bit some episodes I had.

The worst one happened after an overexertion. At night I laid in bed and barely could move my chest. I just lacked the strength and endurance to do so.

My breathing was both slow and shallow. Without putting my every focus to every single breath I took I knew I was getting dangerously low amounts of breath.

I did not know if or how I would make it to the morning, it was that bad. Yet I did not panic a bit, something that would be very normal under those circumstances. I barely thought safe for a short “If I don’t do anything I wont make it through the night”, “I’ll have to focus all my energy on breathing; far smaller PEM problems have tanked my health very deep and costed months or more then a year to recover” and finally “only think about breathing in, breathing out every single breath you take all night; I’ll deal with the damage later”. And so I did. At the end of the night I still fell asleep and the damage afterwards was limited. The strategy of saving all energy and putting it into breathing succeeded ;-).

Later I had similar but less extensive experiences. I could physically not be anxious, feel fear or hate. I put this observation to the test and thought about a very unfair situation that easily gets me angry. I just couldn’t get angry even if I put in extra effort.

I believe it were my adrenals being temporarily unable to push out adrenaline and noradrenaline. Seems without some of it I just can’t get anxious, fearful or angry and to a large extend can’t feel much at all.

Nat, are you sure you don’t have myasthenia gravis? It can be hard to rule out, but they can at least give you a Mestinon trial to see if it improves your breathing.

I get like that as well. The weakness is crazy and definitely can feel death-like at its worst.

Hi Veronique,

Thanks for all your hard work! I have read most of it diagonally to save energy, so sorry if I missed something you wrote about in my comments.

I start from the idea/belief that there is a persistent source of trouble in our body that must activate the immune system but the immune system keeps failing to resolve the problem at hand. Many of the physiological and psychological effects seen are in this view part of the massive fallout of all the partially failing attempts to resolve the problem.

A “decrease in the ability to restore high-energy phosphate stores after exertion”

B “aversion to glucose as a fuel with preference for fat as a fuel”

C ““decrease in the ability to restore high-energy phosphate stores after exertion” (this relates to mitochondrial ATP and energy production)”

D “altered Th1/Th2 imbalance”

E “low body temperature”

F “fight-or-flight”

-> IMO they all relate to very high needs for NDAPH.

Due to the severe underlying immune and inflammatory problems the consumption of NADPH is double: once for producing copious amounts of hydrogen peroxide to enable the strong immune response and once for regenerating glutathion for clearing up the massive amounts of oxidative stress this immune response created.

A -> The body needs to maintain a decent pool of glutathion in order to protect itself against the the large scale destruction if oxidative stress were to get out off control. Under the above conditions this requires massive amounts of NADPH. If recycling of NADPH is insufficient then production of NADH has to be reduced accordingly. The oxidative stress going hand in hand with the production of NADH needed for ATP needs the opposing protective effects of NADPH. Therefore the ratio of NADPH to NADH must be maintained within a relatively narrow band.

If excessive chronic immune activation and relating oxidative stress depletes NADPH levels then this causes the immune reaction to be both excessive and weak. In order to maintain steady state minimal levels of NADPH the immune response need to be toned down (weakening of the immune response). However, if the immune response is (near) body wide then the total sum of all individual weak immune responses around the body is excessive when considering the chronic state.

B -> In order to increase NADPH recycling to a very high / extreme level (in order to maintain no more then minimal stocks due to the very high NADPH consumption) the body needs primarily to maximize the amount of glucose going trough the Phosphate Pentose Pathway and secondary turn as much (parts) of the Krebbs cycle away from producing NADH/ATP in favor of NADPH.

Maximizing the PPP requires to shut down glycolysis as much as possible. That means among others turning the enzymes for glycolysis down and having plenty of the end products (pyruvate and lactate) into the bloodstream as a high amount of reaction products slows down a chemical reaction. Both are seen in ME.

Keeping these end products high means reducing recycling them into glucose by the liver and reduce their consumption. Turning down the Krebbs cycle is a useful tool in reducing pyruvate consumption a lot. This is consistent with ME too.

The nice thing about your hypothesis is that I can’t help but think with all the metabolomics work and more focus on energy production that we should know at some point whether it’s correct. Do you think?

I just came today to an important conclusion of my gut enigma I was working on lately.

I feel strongly it describes (a lot of) Me as in “my version of ME” in a logical and natural way. I think/hope I can put these ideas to good use as well.

Coming in the gut section as soon as I recover from writing this; I intended to write about it today ;-).

Metabolics is just one tool. We have some very clever scientists working on it, but they are few.

The Naviaux/Davis study is already a monument. But as far as I understand metabolics generates huge amounts of data about one cell under particular circumstances, like a ME WBC in ME blood.

That reveals things that are very hard to find or confirm otherwise, like the massive CDR Naviaux did find. I gladly work with his findings ;-).

But ME is a systemic disease. And a system is so much more then the sum of it’s components. As an engineer, I do know that with a handful of components you can make totally different systems. Even with fixed wiring, signals are to a large extend the system.

Your smartphone can enable conversation, be a modem, be a handheld gaming device, a calculator, a hart rate monitor… with no single component or wiring between them changed.

Systems including systemic diseases exit for a large part in the signals that exist in them.

We are lucky with some very smart people using metabolics for our disease. But doing an experiment with a RBC may show very different markers compared to doing the same experiment in WBC or endothelial cells.

They need to kickstart the technology, set up experiments for ME, sort out tremendous amounts of data, learn and see how this data relates to the actual disease…

So yes, at some point in time metabolics will be able to shift through hypotheses and put them to the test. And it will hand more and more information to other scientists. But it will likely have its hiccups due to assumptions in the experiment setup.

We need more talented people in metabolics, but we need more nurses and doctors too who question whether such a low body temperature truly is impossible and who grab a mercury thermometer if their digital device seems to fail. We need more people who just take IR images of hypothermia patients with a 10k$ camera and compare head/body temperature distribution to that of healthy people.

Dirt cheap, may or may not yield results but likely is never done. And we definitely need to get bio-physics really kickstarted next to biology and biochemistry.

When I search for what is the state of the art of a blood flow model to the brain I was baffled. Yes, the simple equations are mathematically correct. But they lead to the opposite of what happens if you just consider blood has to return somewhere too :-(… Or they miss the bloody point that the blood pressure in the brain capillaries need to be closely related to the CBF pressure if you do not want brain hemorrhage… That’s basic material science and strength calculations.

So much basic work to do. We need good and healthy people with a decent knowledge of biology, medicine, physics, mathematics and engineering to get involved too if we really want to get to speed in understanding a systemic disease IMO. When all of the above work on ME and exchange ideas and information then metabolics can help breaking this disease far quicker I believe.

YES – and as patients, we have become experts in exploring symptoms and details with years and years of data under our belts and huge motivation to keep trying to make sense of it all. It’ll be interesting to see what happens with the field of metabolomics. As you say, something systemic is so big and can have so many different inputs, interactions, and outcomes. Metabolic studies just show some of the results and effects, and not exactly what is happening… so it’s just one step. But it helps when multiple different fields of study – looking at the same problem from different angles and wide and narrow lenses – start to see the same thing, as here at Naviaux’ biochemical angle and from the ANS trauma science angle.

Glutathione can be raised through clean diet, immunocal platinum, sulforaphane, fisetin and milk thistle, kale, chicken soup and NAC. I think glutathione is part of it because immunocal platinum seems to really help. Pity I can only occasionally afford it.

Hi Chris,

My eye cought “immunocal platinum”. Platinum is a catalyst used in countless industrial chemical reactions. I had a vague memory that it is used in peroxide related chemistry as well. Then my eye popped on my bottle of one-step contact lens cleaner.

The liquid is mainly 3% hydrogen peroxide with a small amount of additives. I use hydrogen peroxide products as it is one of the few lens cleaning products that can sufficiently remove yeast from contact lenses. In rare cases eye yeast infections can cause blindness.

Putting a lens on the eye with unneutralized peroxide on it causes a very strong burning reaction to the eye. Having frequent mindfog I need a one-step product. It’s just the lens holder that is different: it contains a tiny platinum coating.

Seconds after you put the peroxide liquid in the lens holder you see oxygen bubbling up due to the slow decomposition of peroxide into water and oxygen. In the morning peroxide is gone and the lenses are ready to use.

So your immunocal platinum very likely works by converting hydrogen peroxide in the blood to water and oxygen. Platinum is a catalyst meaning it participates in the reaction but it is not consumed. It can be reused many many times before it degrades / is excreted / is encapsulated in the body.

At “relatively small, chemically speaking” concentrations of peroxide in the liquid the reaction speed of peroxide decomposition is proportional to the concentration of peroxide. That means your immunocal platinum is an “adaptive” peroxide neutralizer. When for example after exertion local concentrations are 5 times higher then normal, decomposition rate increases only there and then five fold.

As peroxide in low amounts is an essential molecule in the body (for the immune system) such “adaptive” nature seems a real bonus here. Having no need for extra energy / NADPH / ATP… is nice in an exhaustion disease too.

The rate of hydrogen peroxide conversion by glutathion is also dependent on peroxide concentration as long as glutathion buffers are not depleted. In ME I believe the decomposition rate is mainly determined by the level of glutathion depletion so in practice it is not truly adaptive.

Having less peroxide at peak exhaustion causes far less glutathion to be consumed. In fact, glutathion is normally not consumed but converted from reduced to oxidized state and then recycled by mainly the liver.

Glutathione does however rapidly lose anti oxidant capabilities if the ratio of reduced to oxidized falls. If it falls to low when we get exhausted then the body has to dump oxidized glutathion, for example by decomposing it into components used for other purposes. When the “peroxide assault” is over however it costs time and resources to rebuild the glutathion stock. So in practice when oxidative stress peaks too high too long glutathion is lost. And immunocal platinum seems to reduce these oxidative stress peaks.

I’m not yet keen on using it as just as much as colloidal silver it’s probably nano particles. Exactly how the body reacts to these is not that well known and platinum is known to be a catalyst in *many* chemical processes. On the other hand, few drugs are without side effects either…

How effective would you rate this product (relative improvement, compared to your best drug or diet…)?

I’ll look into the other products later.

In reesponse to the points on RBCs above. They lack mitochondria, and generate energy quite differently. They also have realitevly little interenal metabolic activity.

They differ so wildly from other cells in the body that they woulf make poor research subjects until ME has cancer or diabetes levels of reearch funding.

split

C -> Exertion is a highly oxidative process producing oxidative stress. If in rest we are near the maximum level of NADH/ATP we can produce (longtime) without the ratio NADPH to NADH to fall through the floor then exercising tanks this ratio really bad and oxidative stress becomes rampant and far higher then the amount of exercise would allow in a healthy person. This is due to the triple lever: more resources shifted from NADPH to NADH/ATP production; more peroxide production due to increased NADH/ATP production; less NADPH available to recycle glutathion => all of this leads to a strong imbalance causing rampant increase of ROS and lactate levels while tanking both NADPH and glutathion levels badly.

Potentially it starts of a cascade pillaging NAD+ stocks to produce the badly needed chemicals (I have to revisit this chemistry, read somewhere about it in a blog of Cort). After exertion the body is in ruin.

F -> No better hormone then adrenaline to increase glucose availability for fueling the PPP to the max. At our levels that means pillaging all usable stocks including decomposing amino acids at very high rate for their glucose, likely creating massive local buildup of nasty ammonia. Ammonia can be converted to anti-oxidant uric acid, but likely not at the rate needed locally. To high ammonia levels are poisonous so that may well set of another cascade of less-then-clean emergency chemistry.

Adrenaline is also a prime hormone for increasing respiration a lot. When the glutathion and the rest of the anti-oxidant systems are completely whacked down then RBC start to bind to considerable amounts of peroxide. Each molecule of peroxide blocks 4 sites for oxygen in RBC and has a far higher affinity to RBC then oxygen. It acts as a somewhat smaller brother of CO. With CO poisonning the best treatment is getting away from the source and supply with plenty of oxygen.

As ME patient it is very normal to hyperventilate badly and for a long time after exertion (feeling very anxious due to lack of usable oxygen and high levels of adrenaline). That is our body expelling peroxide out of the RBC IMO. The mechanism may fail to remove very high amounts of peroxide out of the body quickly but at least it does save the RBC and the brain.

Adrenaline also directs blood flow towards the brain and the liver. During such proposed rampant oxidative stress the liver has a lot of work to detoxify and recycle glutathion.

D -> I did find 1 step in thyroid hormone production to be dependent on NADPH levels. I somewhere wrote a comment on Healthrising about it.

E -> This very hot summer I learned that I could get a heat stroke without having too high body temperature. Many of the symptoms that I previously linked to dehydration persisted when I almost acted like a coffee machine (water in water out so I did not lose the bulk of it due to transpiration…).

Getting into a bath with cold water was not pleasant but it almost instantly revived both my body and mind. This can backfire or be dangerous for many patients!

Lower body temperature allows IMO to drive even more absurd amounts of glucose through the PPP, strongly increasing NADPH/glutathion/NADH/ATP whilst decreasing oxidative stress IMO.

Even when I daily flirted with/around hypothermia my head was not cold. But my body was sometimes very cold (all time low of 33.5 °C in the hospital in a hot room during a heat wave, dismissed as impossible (“digital thermometers…”).

I believe a low body temperature acts as a cooling device for the blood that comes from the brain. The brain has not that much cooling capacity compared to the amount of power it consumes. Having cold blood taking heat away from the brain allows to locally turn up the PPP (with plenty of heat as waste product) a lot, producing anti-oxidant at one of the most critical spots. Many ME patients with low body temperatures use ice packs to cool their head from time to time.

Interesting. Nancy Klimas’s studies show that inflammation hits first during exercise in ME/CFS – the top ten pathways upregulated are inflammatory (!) and then those fade and over the next couple of hours, oxidative stress, ANS and other pathways kick in.

https://www.healthrising.org/blog/2018/10/10/cdc-roundtable-multisite-klimas-reset-chronic-fatigue-syndrome/

Plus the metabolomic studies, if I have this right, suggest that amino acid substrates are being “pillaged” (great word) to provide fuel.

We really need a blog to put this all together 🙂

Hi dejurgen,

It’s good to “see” you again :-).

Your understanding of the biochemistry is well beyond mine so I can’t respond directly to any of the detailed work you’ve figured out even as I completely agree that we likely each have our own unique, individual subset of ME/CFS.

The one way I can respond is with something I noted in Naviaux ME/CFS article, which is specifically about NADPH and that really caught me eye because of his clarity and because it helps explain just how complex the dauer state is (and other CDRs) and how interwoven it all is with so very many other interactions that can cause increases / decreases / absences / reactions… and ultimately, symptoms and the like…. It’s on p es478:

“It is important to emphasize that NADPH is neither the

problem nor the solution by itself. It is a messenger and cofactor.

NADPH cannot work without the availability of hundreds of carbon skeletons of intermediary metabolism needed to carry out the message—the signal that fuel stores are either replete or limiting and metabolism must be adjusted accordingly.

Specifically, NADPH cannot be simply added as a nutritional supplement to produce the tidal change in metabolism needed to shift the dauer state of CFS to normal health.

Incremental improvements in NADPH production could theoretically be supported by interventions directed at folate, B12, glycine, and serine pools, and B6 metabolism (SI Appendix, Fig. S6), however the safety and efficacy of these manipulations have not yet been tested in a rigorously designed clinical trial.”

What it may come down to, at least for now, is that we may very well be able to identify individual patterns of metabolic function with testing in the future as Naviaux’ work continues, and that in the meantime each person has to experiment to see just what DOES work and what actually does help with their own set of biochemical interactions in their system.

Hi Veronique,

I enjoy talking to you too. You demonstrate an open mind and willingness to share ideas for better understanding rather then as a dogma.

Thanks for citing dr. Naviaux’s ideas on NADPH. I don’t recall having read them before.

I do agree that adding NADPH is not the way to go. Adding glutathion is no clear cut either IMO.

I consider doing things to increase the production of NADPH and glutathion to be only a small step as well.

Their true power lies in how many times and how quickly they can be recycled. And there I believe we can work together with our bodies to better reach the goal. No cure, but improvement.