“New data collectively supports the presence of specific critical points in the muscle that are affected by free radicals.” Fulle et. al.

A group of pioneering Italian researchers have been studying the muscles of people with ME/CFS – a rather lonely task – for over 15 years. Hailing from the Universitá di Perugiá in Perugia, Italy, they’ve poured out muscle studies in ME/CFS every couple of years. Why do they keep to their rather lonely task? It’s probably because they keep getting intriguing findings.

In very broken English, the Italian researchers laid out their conception of chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS).

Old Muscles?

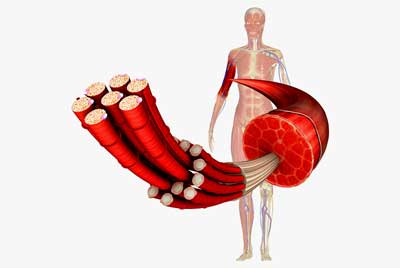

With the exercise intolerance present, muscles present such an intriguing area for ME/CFS. The authors believe the muscle problems found in ME/CFS look more like aging than anything else.

(If that’s true there must be a lot of aging going on in this disease. Many times I’ve been overtaken on my short walks by quite elderly people walking by at what seemed to me to be a remarkably rapid click.)

Just as in the elderly, the number and size of muscle fibers in ME/CFS are reduced. Plus problems with calcium transport may be producing fatigue in both people with ME/CFS and the elderly.

The type of muscle fibers present may also be altered (fast-twitch muscles predominate) while basic contractile properties of the muscles remain intact. Those fast-twitch muscle fibers get fatigued more easily and require more energy.

The Culprit – Oxidative Stress?

The mitochondrial, muscle and free radical issues found in ME/CFS point a finger, these authors feel, at one culprit – oxidative stress. (In the brain, Dr. Shungu is pointing his finger in the same direction.)

With all the inconsistencies in ME/CFS research, it’s rather reassuring that every study – whether done in the brain, muscles or blood – that’s looked for oxidative stress in ME/CFS has found it elevated.

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) or free radicals are produced in abundance during energy production and particularly during exercise. Our cells usually easily mop up those free radicals, but damaged mitochondria can produce enough free radicals to overwhelm our anti-oxidant system. If things get bad enough the cell may even die. Plus inflammation – a prime target in ME/CFS – can produce scads of oxidative stress as well.

At least three studies show that exercise abnormally increases levels of free radicals in this disease. One study suggested that those free radicals could be having real consequences: they were associated with impaired energy production in the muscles of people with ME/CFS. Plus, the membranes of the muscle cells – which free radicals love to nip at – appear to be damaged as well.

One study found higher levels of free radicals were associated with reduced energy production by the muscles in ME/CFS

Furthermore, indications of oxidative damage were found in 66 muscle biopsy specimens from ME/CFS patients. A study of the gene expression in the muscles of people with ME/CFS found altered expression of the genes involved in mitochondrial functioning, oxidative stress, and muscle structure and fiber type. All in all, it appears that ME/CFS patients’ rather weak antioxidant systems may not be keeping up with what appears to be a torrent of oxidative stress.

That oxidative stress could be damaging the mitochondria and the ability of the muscles to contract and produce energy. One study reportedly found that a group of ME/CFS patients with a severe infectious onset had the trifecta – high levels of free radicals, even at rest, their muscles were mostly dead to the world (didn’t respond to exercise) and had ion channel problems that may have affected the ability of their muscles to contract.

An exercise/gene expression study found similar evidence of a strange non-response to exercise. Contrast the 50 genes that became activated during exercise in GWS and the one that got activated in ME/CFS and you get a picture of a moribund metabolic system that cannot rise to the occasion. That finding fits in well with evidence that the sympathetic nervous system also poops out during exercise.

Inflammation the Key?

Could it all come down to that ubiquitous bug-a-boo, inflammation? One review suggested that low grade inflammation plus chronically high levels of free radicals could explain the muscle fatigue so often seen in ME/CFS. A 2014 literature review found some evidence that exercise is producing immune changes in ME/CFS.

Nancy Klimas’s extensive sampling before, during and after exercise appears to have captured the process. That study found that a remarkable upregulation of inflammatory pathways occurs during exercise in ME/CFS, which is followed some hours later by a similar upregulation of pathways involved in oxidative stress and other processes. The inflammation comes first and produces, among other things, a dramatic increase in free radical production, which causes damage and almost certainly contributes to the PEM experienced.

Conclusion

This Italian group and some U.K. researchers have been carrying the torch for muscle damage in ME/CFS for over a decade. The results have been intriguing but have not yet lit the world on fire. Muscle studies in ME/CFS are still relatively rare.

Given enough funding, that could change soon. We have a new and potentially very powerful entry into the muscle field – one that has already been opening doors that have heretofore been closed. Ron Tompkins, the leader of the Open Medicine Foundation funded ME/CFS Collaborative Research Center at Harvard, is eager to dig deeper – much deeper – into ME/CFS patients’ muscles than has ever been done before. Another one of Ron Davis’s longtime comrades and collaborators, Tompkins has got the facilities he needs and has quickly gathered the collaborators needed to crack this area of ME/CFS wide open.

If Ron Tompkins can get his funding we’ll learn much more about the role muscles problems play in ME/CFS

Tompkins has quickly managed to gather a rather remarkable team. Specialists in bioinformatics, muscle biopsies, muscle metabolism, proteomics, sepsis, medical genetics, inflammation, sleep and others are sprinkled throughout his team. Among others, Dr. Komaroff, Michael Van Elzakker (Vagus Nerve Hypothesis), David Systrom, Janet Mullington and Wenzhong Xiao have joined the team. One team member, Dr. Felsenstein MD, has been following some of her ME/CFS patients for over 20 years.

Tompkins, who has lead some of the biggest and longest NIH funded studies ever, clearly hasn’t had much trouble gathering outside researchers into his team. His problem is not finding good people to work on ME/CFS; rather, his problem will be gathering enough money to maximize their talent. Getting funding is not easy, but it’s actually far easier than gathering top talent: Tompkins’ problem is not a bad one to have.

Given enough funding, Tompkins and his team have the potential to blast open our understanding of the role problems in the muscles play. For me, with all the PEM that mild exercise brings, it’s hard to imagine that all the threads of ME/CFS research – the autonomic nervous system, metabolic, central nervous and immune system problems – don’t in some way meet in the muscles. They could provide a window into the heart of this disorder.

Welcome back to 1980.

Keep old theories around long enough and they come back into fashion.

I’ve been taking high-dose Vit C (at least 8g per day) for years now, because if I don’t, my muscles all stiffen up. Even with it, if I do very mild exercise I tend to ache all over.

Hi Londenpost,

a kidney specialist said to me once that the maximum of vitamin C you may take is 1 gram a day. So please watch out for your kidneys.

best of luck!

Look into magnesium glycinate.

Interesting. I do remember that Moreau was finding problems with Vit C – although I can’t find the report right now.

When a human demineralises for one reason or another bring infection or through inherited DNA the a larger than life issue is absorption

My husband noticed (and he is surprised that I can’t feel it) that fibers in my muscles (not whole muscles) all over my body, constantly twitch. Even when I sleep. They are onto something. Keep on researching.

I twitch all over and it has gotten worse. My doctors seem baffled.

My muscles are on the verge of spasm all the time. I have an off-on relationship with Magnesium supplementation but not by mouth. [MgCl2 foot soaking, oil spray – helps my sleep for a few months at a time] Weekly injections of MgSO4 used to work wonderfully for a year. Until I took it by mouth, then no form of Mg worked. Its my battery fluid for Flat Battery Disease [ME/CFS lol], but its an ongoing problem to get it absorbed. Yes, 1980 again.

I just heard of someone who’s done wonders on Re-Mag – a liquid solution developed by Dr. Carole Dean. It did wonders for his gut actually.

https://amzn.to/2JLbDHu

I’m the same, constantly on the verge of muscle spasms and twitching. It’s at rest I notice and actually ‘see’ it. When I relax by sitting or laying and all muscles are really relaxed it’s then I start twitching like a fish out of water. Like little electric shocks that zap and twitch all over and around my body. When I’m severe and I’m having a really bad day it’s as though my whole body suddenly jumps/convulses as I lay there. Really horrible feeling. Anybody else experience this?

“When I relax by… …it’s then I start twitching like a fish out of water.”

I never got the twitching that bad, but yes it’s pretty normal in ME/FM. For the convulsions it’s a bit difficult to know if I got translation correct. If that is the epilepsy like shaking then yes I had that badly. At times I had to push my one fist into my other hand palm in order to not get my whole body violently shaking. It acted like redirecting all the forces to the hands. I did push that hard that it felt like I was crushing my hands.

For the epilepsy like shaking I one morning recognized it as a rather strong form of shaking to get the cold out of your body. When checking out my body temperature I indeed was into hypothermia zone. I know I easily had cold but did not know it was that bad. I kinda got used to having a cold feeling. Trying to increase my body temperature did backfire with increased inflammation. Cyclists do cool their body after competition in order to reduce inflammation and it appeared my body did the same. Unfortunately that cold body temperature made muscle biochemistry very inefficient and made my muscles prone to damage when moving.

I solved this “deadlock” by accepting the low body temperature during most of the day and only did very mild “warming ups” (few very light circulation exercises) before “exercising” (getting from the bed to the bathroom, from the kitchen to the porch…). That gave me low average body temperature reducing inflammation and kick started the flow of blood when “exercising”, making exercising a little bit less damaging (slowly reducing micro damage and inflammation over time).

Doing neck circulation exercises was part of it: the brain needs decent blood flow as well for coordinating all this “complex” movements. Note: as neck circulation exercises can block some nerves, always ask advice from a professional!

In less then a month pain levels decreased significantly by just doing that. Over many months body temperature got out of this hypothermia zone into just low. For increased exercise ability a whole lot other things were needed though.

As for the twitching, I learned to recognize it as “healing/restoring” rather then damaging/problematic.

When I slowly got better health, the feeling more and more appeared hand in with slight improvements in health and recovering from exercise. When I had it, I recovered better. The smaller the twitches the better they were. It was like with champagne: the smaller the “bubbles”, the better ;-).

That learned me not to waste energy fighting them (and loosing their healing gift), but rather relax and enjoy them.

I believe the following happens. Even with healthy people, muscles shorten a bit after exercise and tend to form little knots. If body chemistry is very inefficient and dirty, body temperature is low, and muscles and fascia are full of damage then this IMO gets a whole lot worse. Then I believe the muscles, even after the tiny exercises we do, become one “bowl of spaghetti” where most muscles and even parts of single fibers are dislocated a lot from their “correct” relaxed position.

The twitching then is like giving a short but stronger pull to a part of a muscle or even a single fiber to see if it can get moving and slide to a better more relaxed position. That reduces harmful strain to that part of the muscle and increases range of motion for a later time.

Compare the short strong pull to trying to move a heavy cupboard. You constantly push and nothing happens. It costs plenty of effort for no result. Then you take a step back and run into it. The cupboard suddenly moves half a feet backward. Rinse and repeat.

The “small bubbles of champagne” here indicate that your body is working out the last strain out of individual fibers IMO. That will only happen after a looong time of the bigger contractions slowly restoring your muscles over many months.

If Phil were to read and comment this blog, he could tell you plenty more. He’s the expert on the topic over here IMO.

Forgot to mention. Doing tiny series of light circulation exercises spread over the day not only allows to improve blood circulation but also offers opportunities for the “stuck” muscle to fold back in place.

As those exercises are done in small series and after resting, they are done when reserves are replenished again a bit. So they happen under better circumstances. As they are short and light, they do not increase “muscle dislocation problems” but by moving the fibers they rather offer the option to get unstuck and rest in a better position.

So circulation exercises and twitching cooperate to reach the same goals IMO. When you dislike the twitching, small spread circulation exercises spread over the day does can reduce it IMO.

I experience this as well. The zaps sometimes becomes extremely strong. I’ve recorded and showed to 3 doctors who all agreed it was myoclonus.

Karin,

I experience muscle twitching quite often. However, as opposed to being a horrible feeling, for me, I constantly try to induce the twitching because it takes away my muscle pain for a split second. Like Dejurgen, I believe my muscle twitching is a way of my body and mind trying to heal itself and release tension. I think it has something to do with somatic neurons functioning. The more relaxed I am, especially after light circulatory exercising, the more qualitative the twitching. Certain medications and supplements can help my muscles relax. They always are so tight. Picture a tire filled with maximum PSI or a balloon ? with too much air. This is how my muscles and tendons always feel. It is like I need release. Very light elongated yoga stretches seem to help but I can’t sustain the release and sometimes I can’t tolerate the exercise intensity. Also, I noticed that when I take 100 mg of trazadone for sleep, the twitching increases exponentially. However, I am pursuing 100% holistic supplementation now and healthy living so I no longer take trazadone even though it seemed to be helping. I hope this feedback helps.

Muscles aren’t where the trouble in ME/CFS start or end, but they are definitely an affected part of the system, resulting in pain, stiffness, lowered capacity and delayed recovery. Finding out what is going on in the muscles will add to the understanding of this illness but I am not sure where it will lead in terms of possible treatments. But maybe learning more about how to handle any exercise and recovery from it, would be helpful. Some of us keep overdoing because things need to get done, etc., and maybe with a clearer understanding of what is at stake in terms of greater damage, not just temporary discomfort and fatigue, would result in a more suitably tailored lifestyle.

In February I started having periodic “seizures”. I have seen a neurologist and he called them pseudo seizures. In essence that means that my seizures don’t fit into any normal category. Recently, during an er visit, a nurse spent time watching my seizure and then remarked to the doctor that the movement appears to be more like that of Parkinson’s tremors. He agreed.They used the word dystonia. However, the doctor said he did believe it was Parkinson’s because the movement wouldn’t stop. I wonder if this would be symptomatic of the art I me a theories.

Yes!!

Sorry, I meant to say I agree with Cecelia. Twitching could be due to calcium release by the sarcoplasmic reticulum, the major storage site of calcium in muscle. Muscle cannot twitch without calcium. I wonder if this is triggered by improper release Ach in specific motor units – this would cause a twitch. Reason some people have relief with Mg is bc it is required for the myosin-actin cross-bridge to be in the relaxed position.

With respect to losing fibers, that would be unusual bc muscle fibers are post-mitotic. It is known to occur in primary muscle disease (necrosis). It is very difficult to count muscle fibers, especially in humans. Reason is that when you take a biopsy you are only sampling the whole muscle. You can’t take a cross-section of a biopsy and count muscle fibers. No doubt where there’s pain, there’s inflammation.

I find it hard to even conceive of the muscles not being part of the problem. It was the main thing that got my attention because I instantly became unable to stand from a squatted position. My muscles literally did nothing and all I was doing was squatting down by the garden bed pulling a few bits of early spring weeds. My friend’s 80 year old mother asked if I was okay when I started rolling around into odd positions on the ground trying to find some way that my leg muscles would take hold. I couldn’t figure out a way to get up off the dang ground! and there was no furniture to crawl to to assist me in standing. it’s kind of scary when you’re stuck in the middle of nowhere with nothing to help you up and your legs are not working at the moment. It was a permanent loss of muscle strength and it was overnight.

I was affected immediately in the muscles of my legs. my arms didn’t give out totally after a simple activity until a few years later.

my hands and legs went first.

the hands (I don’t think) are muscular? but inflammation setting into the hands rapidly upon using them at all is a definite yes!

They are so weak I can’t carry a gallon of milk without my fingers giving out. Hand braces help with that,

A ridiculous example of how weak my hands became overnight..

here’s A self-help method I came up with when making a pot of coffee To enable me to get that heavy carafe of water filled, lifted and poured into the coffee maker. I’d place my 12-cup coffee carafe onto the sink bottom, fill it with water, then lift it with 2 hands and pour into coffee maker by using 2 hands, I’d brace the edge against the top of coffee maker housing, then while guiding the spout with my right hand on the handle I lift up the bottom of the carafe with my left hand.. the housing bearing the weight load, the carafe tilts easily. No real lifting required! brilliant!

once, though, I forgot to set the carafe on the sink bottom and filled it like a normal person.. hold it in my left hand by the handle under the faucet with my right hand on the cold water thingy (no word in head 4 it).. and as it filled with water, my left wrist gave out on the anterior side… which isn’t the way the wrist bends. . I heard a loud snap and felt the kind of pain that makes it hard to speak for a bit. it swelled so badly my hand was dead feeling for 36 hours. at least I couldn’t feel the pain with it totally dead to feeling. I didnt bother with the doctor because all they’ve done in the past is say “Yep! its broken!” and done nothing as they had been bones in my feet.

but, When the swelling subsided.. the pain became rather insistant, and the bruising showed up… should have gone to the doc.. as I now have limited range of motion in that wrist and can’t rotate it enough to hold my hand palm up.

I can do a great thumbs up though! And the injury was 5 years ago…

And edema. my tissues swell so much with little activity. And I don’t know if anybody else has a phenomenon where you can feel heat coming off of an area that hurts and is swollen after you use that muscle group? But the heat radiating off of various areas on my body after activity really backup my vote for inflammation.

I have chronic inflammation in my hips and the doctors believe it’s bursitis because steroid shots to the hip always heal it. But it always comes back.

That started when I was 40. So for 17 years I haven’t been able to lay on my side because of the pain in my hips. Obviously steroid shots in any joint are not something you want to do often unless you’d like to have a joint replacement.

Short term dose of Methylprednisolone makes me feel much better when I’m extremely sick and in too much pain, with heat pouring off my body, and laying there crying.. hanging my feet and hands off the bed.. no blankets on toes either! I wonder why steroids help?

I’m very curious to see what looking into the muscles of ME/CFS patients turns up.

I wish they could get you into one of these studies Maschelle!

Mucho se habla del magnesio y poco del calcio que interviene en todas las contracciones (voluntarias e involuntarias) de los músculos,incluido el del corazón;magnesio y calcio deben de estar en equilibrio,son antagonistas y dependen de la acción de las glándulas paratiroideas PTH y de la Vitamina D3 y sus receptores,las tetanias o contracciones-espasmos por calcio bajo (calcio corregido por albumina,lo indican)el calcio alto de alguna manera produce parecida sintomatología,revisar el Metabolismo del calcio,magnesio PTH y V.D3 no estaría de más,pensando que además la solemos tener baja y que de rutina no lo hacen,revisen esto por favor

about muscles, I have 30 years me/cfs and my bloodwork was allways good. But I was the type that I could do after the first period of being verry bad, moere. I gradually became more and more ill.

the last years my bloodwork is not so good anymore and I have 1 big concern and that is that my bloodwork shows heart dystrophy. I am a long term severe cfs patient but I have never read or heard about heart dystrophy in cfs. Yes, well that we could earlyer die from hartfailure. does anyone know more about this or is it just atrophy like with all my muscles?

Paul Fournier at University of Western Australia is also studying oxidative stress in ME/CFS using muscle biopsy before and after exercise. They found significant results but not sure if they have published yet. It was an interesting experience being involved in this study, the doctor doing the biopsy after exercise on the second day thought I had been sedated I was so out of it.

No kidding. Talk about a timely study. Looking forward to that. Thanks for passing it on.

I have had ME/CFS as well as 2 family members of mine hence genetically.as well mine is the trifecta that I have track the timeline of things that have had that set this in motion on myself.Everything that I have read and researched and especially since I just came across you and your posting_just recently is spot on! In reference to muscles, yes there is a corlation as I have that problem especially bad in the knees getting up out of sitting and crouch postion early onset DX in my 30’s of severe Osteoparosis! In reference about funding I can only say that back when the Million Letter Campaign was going on the Late Senate Kennedy (Mass) was working on a bill for funding so there is a possible interested supporter there! My mom had similar symptoms as well in her younger years and eventually develop and Dx with ALZ.and right before her death was Dx with head,lung and breast cancer so you are on the right track and a 2016 something was passed for funding/research,ect.The Prevention Act (Moonshot) on ALZ and

Parkinson diseases in Congress NIH is aware of this Action another one that should help and support reseach! Please keep up your research and posting your findings everyone as I still have faith, hope and pray that together nothing is impossible and a cure will be found

I wanted to correct this I have fibro. hence genetical female family members with overlapping symptoms of ME/CFS hence the trifacta effect for me and just now looking into ME/CFS..so bare with me and thank you for sharing and caring..

Due to my brainfog and recall this comment is in reference and in regards to funding possibilites to my other posted comment:

As you may know, the 21st Century Cures Act was signed into law on December 13, 2016, this bipartisan package that aims to accelerate the pace of cures in America by reforming the regulatory processes of the National Institute of Health and the Food and Drug Administration. Major reforms include integrating patient perspectives into the regulatory process, modernizing clinical trials, incentivizing more scientists to pursue research as a career, and promoting personalized medicine. Additionally, it provides the NIH with $4.8 billion dollars in new funding that is fully offset and targeted towards advancing projects like the “Cancer Moonshot” to eradicate cancer and the BRAIN initiative to improve our understanding of diseases like Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s.

I’m becoming increasingly convinced that all the abnormalities researchers have been finding are simply the result of a body being put into a hypometabolic state. If you look at the research being done by NASA of how to put humans into a hypometabolic state by chemical means or research on hibernation/torpor states in general you will find a lot of overlapping ideas.

It would seem to me that inflammation and ROS increases during and after exercise because we are not meant to be exercising while in this hypometabolic state. When animals come out of hibernation, for example, ROS also increases temporarily.

Maybe I’m just crazy but it seems that NASA should look into ME/CFS. Wouldn’t that be great?!

Ron Davis thinks so – if I remember he tried to get data from NASA on the astronauts in order to assess the severe ME/cFS patients better. Unfortunately the data was gone…

Cort, this is not surprising. NASA holds some of their data close. Part of the reason is that long-term exposure to microgravity markedly changes the physiology of most systems. They don’t want to show how ill the astronauts are upon return to earth. I had NASA grant awards during the 00’s, then their budget was cut dramatically.

Hi again Cort and guys

In regards to the Oxidative stress, I’ve been testing Astaxanthin 4mg daily, and I have to say you do notice a difference in both energy levels and a reduction bin inflammation.

I did start with a higher dose of 12mg but I concluded that it was too strong a dose for me, and you know how sensitive our bodies can be to anything new.

I have noticed a strange side effect though, and I’ve had this from a few other things over my 10 year illness. I,ve noticed this inner ice cold sensation. My body is normally the other way, in that it’s always warm and has viral symptom’s.

I assume that this problem with the muscles also applies to the heart, and it is also aging faster.

I would guess so. It should be noted, though, that there is no evidence of increased heart disease in ME/CFS that I know of. IF all the muscles are effected I would imagine the heart would be the last to show effects.

We should remember as well that this is a hypothesis. We will know much more if Ron Tompkins can get the funding to carry out his work. If he can do that I think we’ll get a clear picture of what’s going on.

Great information Cort; so good to hear of this research! Thank you!

My muscle symptoms are different from other commenters. One of the first things I noticed after the onset was the difference in muscle pain after exercise or activity. After ME/CFS I experienced flu-like muscle aches. Before onset, exercise would result in what I describe as more bruise-like — that feeling that lets you know you did something different — a feeling that would go away in a few hours or a day afterward. I’ve also described the muscle difference as feeling brittle, like old elastic. As I’ve aged, I’ve experienced more weakness that seems disproportionate to just the aging process.

I have also been told by two massage therapists that they can feel a difference in the muscles of individuals with ME/CFS and Fibromyalgia.

Muscle involvement seems like a significant factor in this disease. I’m grateful to hear there is research looking into this!

“Before onset, exercise would result in what I describe as more bruise-like”

I experience different types of muscle pain depending on moment/conditions. Would that bruise-like pain be what I call “cold damage”? It’s sore, not warm nor hot but closer to pain you feel on a rainy cold day and it does not feel acid nor burns?

If so, that is what I believe to be micro damage spread over the muscle without sufficient inflammation. Infection of the damaged spots may occur. As inflammation is supposed to be a healing mechanism (if it does not go wrong as it often does in ME/FM!) this leads to accumulation of damage over time in the muscle.

“After ME/CFS I experienced flu-like muscle aches”. Only had the real flu once really long ago so I forgot. Is it more of a glowing aching burning acid like sensation? If so, then it is what I get when I believe sufficient damage has accumulated into the muscles so that the body can not longer suppress inflammation without risking damage to accumulate too much. Plenty of rest is needed in order for inflammation to not go wrong. This would be a period of greater fatigue.

Would it be something like that you experienced?

For me it’s not flu-like sensations in the muscles – it’s just general flu-like sensations which are hard to describe.

dejurgen thank you for your reply. I regret that I can’t clarify the distinctions. The pre-ME/CFS was a very long time ago and the flu-like subsided a number of years ago.

You have a clear idea of the muscle symptoms you experience. I hope you are able to find relief.

For me I’ve tended to experience burning, contracted feelings in the muscles after exercise. I think the “brittle’ feeling might apply as well. Sometimes when I really overdo I got those flu-like symptoms. If I had to choose one I would choose burning sensations 🙂

Interesting observation from the massage therapists! I wonder what they felt.

Boy the variation in muscle (and other) symptoms among PWC is amazing isn’t it Cort? My next hope for research would be the subsets in this disease.

I wonder too what felt different to the massage therapists.

I’m also curious what the massage therapists felt. I’m going to ask my massage therapist as well. I’ve thought that my connective tissues feel and sound like dried rubber cement.

Cort, as always, thank you for your so much appreciated work.

Muscle involvement seems almost obvious given everything else we know. I am curious as to other’s pre me/cfs muscle experience. I have always been ‘strong for my size’ and was, like most of us it seems, very physically active and driven to push myself because it was a source of pleasure and, yes, pride. Now that I am doing pretty much nothing and definitely nothing I’d ever have called exercise before, my muscles are still quite firm when flexed. So many times I have thought ‘I am never really relaxed’. I do get twitchy at night (sorry, husband) and have spasms. Magnesium sometimes seems to help but maybe not? CBD does help if I use it regularly as a maintenance supplement.

Good heavens we’re complicated!

Love and healing to everyone.

Revisar Metabolismo del calcio y minerales no estaría mal,se le da importancia al magnesio que relaja,pero el que contrae,crea espasmos:tetanias, debilita y duele es el calcio bajo (corregido por albumina,a veces el alto tambien),este depende de la Vitamina.D que está baja o inactiva y ese calcio no es disponible,tampoco evalúan la PTH en Analítica de rutina,es indicador del buen funcionamiento de paratiroideas,el calcio puede no estar llegando a las células,los síntomas son los mismos,solo que no lo testean habitualmente