This is the first of a couple of blogs that will celebrate visionaries within the ME/CFS/FM communities who took action to make their visions real. Dr. Bateman was doing yeoman’s work serving the ME/CFS/FM community in her medical practice in Salt Lake City, Utah. She could have kept doing that – and been satisfied with the knowledge that she’d dedicated her career to serving some of the most in need.

It wasn’t enough, though. With too few people being served she decided to make a startling leap. She would transform her small private practice into the much larger non-profit – the Bateman Horne Center – in hopes that it would garner the funds needed to serve many more people – not just patients in Salt Lake City – but patients, researchers and doctors across the world.

Nobody in the ME/CFS or FM communities had attempted to package a clinic, research and educational facility together in the form of a non-profit. With that change, Dr. Bateman lost the ability to steer her own course – the Board of Directors is now in charge – but she gained the ability to apply for grants, do fundraising and expand while maintaining her set of ideals. Transforming her practice like that was a bold move that required vision and lots of guts.

I was there to see how and what the Bateman Horne Center was doing.

________________________________________________

I was late – again. I’d camped out east of the city at about 10,000 feet. I had almost despaired at finding a place to camp until I found a nice well-travelled dirt road leading into the mountains. I headed straight up a slope for about a mile, looking at my cell phone all the way. At the top, I got a signal and stopped.

It was a gorgeous scene of huge dry meadows interspersed with thick stands of fir and spruce. That afternoon we were visited, for the first time, by several hundred goats and their South American herder. Two windy days later I was heading back down. The cell phone told me I was 1/2 hour away from Salt Lake City. That seemed dubious given I couldn’t see hide nor hair of a city. Getting on the road, I checked again – the Bateman Horne Center was now an hour and a half away – and I was going to be 30 minutes late, at best.

It turned out I was just 30 minutes late and Suzanne Vernon was there to say hello. I had no idea what to expect with the Bateman Horne Center (BHC). I knew that in a bold move, Dr. Bateman had thrown her cap over the wall, so to speak, and in an effort to see more people and build a sustainable clinical practice, research and education center, had turned the clinical practice and the education non-profit she’d formed 15 years ago (OFFER) into the Bateman Horne Center (BHC) non-profit.

It was impressive from the get-go. The front office, with its full suite of windows, was light and inviting. (An atrium addition is planned.) Suzanne led me down a long corridor of clinical and treatment rooms (a Cortene study member was in one), offices and meeting rooms. I had imagined something much smaller and was unprepared for how big the facility is.

Several RN’s and physician’s assistants, an intern working out of what looked like an open office in the middle of the facility, Dr. Burkeleau – a physiatrist (pain doctor) now working at the BHC, and the Communications Director.

Suzanne Vernon, PhD. – Research Czarista

In Suzanne Vernon’s office, how important the BHC is (and how rare it is) became readily apparent when I asked Suzanne what this field needs most. She immediately said she thinks back almost every day to something FDA Deputy Director Sandra Kweder said in a phone call in 2012 and at the FDA workshop in 2013.

(Sandra Kweder has quite a resume, and is now Deputy Director of the FDA’s Europe Office in the Office of International Programs (OIP). A high-level official at the FDA, she appeared to take quite an interest in this disease.)

Dr. Kweder’s assertion that core areas of ME/CFS still needed to be characterized produced a “wow” moment for Suzanne Vernon.

Kweder said that the only way this field can move forward is to go back to the beginning and define the core signs, symptoms and decrements of specific functioning.

That’s not sexy; it’s not some huge research breakthrough – it’s simply what drug companies and others need to feel it’s worth their while to get involved. Suzanne said it was a “wow” moment for her. That slide is ingrained in her memory. She instantly realized that the field had overshot – it had gone for the research goodies without creating a good foundation first.

We have, fortunately, made progress in this area since then with the IOM report and the Common Data Elements (CDE). The IOM report provided the roadmap to defining the core criteria and CDE provided preferred protocols.

The BHC uses the CDE’s in its very rigorous workup of patients and healthy controls, not just for treatment purposes, but to ensure that they are research-ready as well. It’s that kind of rigor that had the BHC filling the clinical core of two of the three NIH research centers. It’s also why we as a community so need the BHC to thrive and expand.

Nothing may screw up this field faster than research projects done on people who don’t really have ME/CFS. The need for “real ME/CFS patients” is why the NIH required the research center applicants to all have a clinical core. It’s why Avindra Nath of the Intramural Study uses strict criteria and a core team of ME/CFS experts to assess each person who wants to enter the study.

Suzanne said that as she watched the presentations at the IACFS/ME conference, she wondered how many researchers had access to those kinds of patients. Then she made a bold assertion:

“We shouldn’t be doing any science without having a clinical collaborator, period. We need to find out how to clone Cindy (Bateman), we need to clone Dan (Peterson), we need to clone Nancy (Klimas) or partner scientists with these experts…Otherwise,” she said, “who are you studying? It’s a huge deal…”

Finding Waldo

Vernon has asked before, where is this field going to get the patients it needs when the research ramps up? The BHC got a first glimpse of what that will involve when Unutmaz’s NIH Research Center asked them for several hundred short-duration ME/CFS patients.

Long-duration patients the BHC had lots of – short-term not so many. They had to get creative to find them. They did so in a number of ways. Dr. Bateman gave lectures at local networks of doctors, to the University of Utah, and to Intermountain Health Care – a Utah-based not-for-profit system of 23 hospitals, 170 clinics, and over 2,000 doctors – on how to identify people with ME/CFS. Thus far, the BHC has checked out over 800 people, about a third of whom qualify for the study.

The Research Center grant is having a tremendous add-on effect – it’s bringing more doctors and patients (mostly previously undiagnosed) into the field. The BHC now has a trained cadre of local doctors who can recognize ME/CFS and, when necessary, send them their patients. The BHC openly tells these doctors to send them their most difficult patients.

Research

Dr. Vernon’s heart is in research. She got bit by the ME/CFS bug 25 years ago while at the CDC where she brought big data into the field for the first time in a major way. This included bringing in Gordon Broderick, who later built the core of Nancy Klimas’ computer modeling team. That team has provided many insights into ME/CFS and laid the groundwork for the treatment trials now underway in Gulf War Illness and ME/CFS.

The Pharmacogenomics study was the first to combine gene, gene expression, clinical and laboratory data together in ME/CFS. The effort was later abandoned by Dr. Reeves.

Back in the early 2000’s, during some really dark years for ME/CFS, she somehow enrolled 20 researchers (most of whom worked for free), to analyze a large data set gathered from a 2-day hospital visit by CFS patients and controls. That massive project is an unprecedented achievement – an entire issue of The Pharmacogenomics Journal was devoted to ME/CFS in April 2006.

After a falling out with Reeves, Vernon joined the then CFIDS Association of America (now the Solve ME/CFS Initiative), created the first Biobank for ME/CFS, lead frequent collaborative efforts at Cold Springs, revamped the research and brought several new researchers into the field.

Bateman Horne Center Research

I asked Suzanne about the BHC’s research efforts. She said the BHC is establishing relationships with University of Utah researchers and others who didn’t have a clue what ME/CFS was before but are now hooked and excited and are applying for grants. Vernon said they are going to be discovering things they wouldn’t have even imagined. She’s characterizing ME/CFS as a place a researcher can make a real difference in a disease. That message has worked – the reception for ME/CFS has been uniformly positive.

Biomarker!

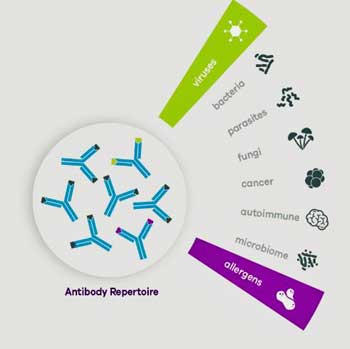

Suzanne said her bias has always been biomarkers; for diagnosis and to use for interventions. The BHC’s work in this area demonstrates her strengths – the ability to reach out and get others interested in this disease. She said information plus credibility gets her in the door, and once she’s in, people often get hooked – just as she did 25 years ago.

The Serimmune study (described below) highlights how important it is to have well-connected researchers in this field. The story began with Linda Ivey, a former collaborator of Suzanne’s. Ivey co-founded 23andMe and then founded Precise.ly – a company which has developed a personalized approach to disease – and which is producing the patient portal for the three NIH-funded ME/CFS research centers.

I don’t know what Ivey’s connection to ME/CFS is, but she’s apparently been interested in this disease for quite a while. Precise.ly Inc’s first app will be focused on ME/CFS. Suzanne Vernon noted that:

“ME/CFS is unique to each person…We need patients to help us identify these unique characteristics of ME/CFS. Precise.ly puts patients at the center of this fundamental first step for a deeper understanding of this disease.”

Dr. Vernon on Precision Medicine for ME/CFS and FM

Ivey knew Patrick Daugherty, the Director of Serimmune, an immune-monitoring startup created in 2014. (Kristin Loomis of the HHV-6 Foundation is on the Board of Directors). She knew he was interested in infection-caused illnesses and put him in touch with Suzanne.

Serimmune has the ability to assess a billion antigens. They mix a patient’s blood with small peptide sequences (antigens). Depending on what those peptides latch onto, they can tell if a person’s immune system has been exposed to a pathogen or is reacting to an allergen, toxin, something in their own body, etc.

Enter the Bateman Horne Center Biobank. Suzanne Vernon has always loved biobanks, and for a good reason – not only can they cut the costs of research significantly, they can get a research project going quickly, cutting substantial amounts of time off the length of a study.

Three days later, hundreds of samples were on their way to Serimmune, and three months later, the results were in and they were good – good enough for Serimmune, a mere two weeks later, to apply for a grant to the Small Business Innovation Research Unit of the NIH to support further work.

It’s this kind of nimbleness and speed that makes our private research groups like the BHC, the OMF, and the SMCI so valuable.

Suzanne wouldn’t say what the results were, but she speculated about using them to uncover infection-associated and autoimmune subsets in ME/CFS.

The BHC’s Biobank already has over 5,000 samples from about 500 individuals. With its well characterized patients, it’s the kind of biobank researchers want to collaborate with. They know that they’re getting the real deal – people who actually have ME/CFS or FM – in their studies.

The BHC is now sending Serimmune another large set of samples – this time from short-term patients. Once those are in and evaluated, they’ll be able to compare those results to the previous results from the first batch of mostly long-term patients.

Feet on the Floor…

One project seeks to identify a key functional outcome – a huge need in this disease. Defining functionality is now done mostly with questionnaires, but what if there was a physical way to determine functionality in ME/CFS?

Dr. Bateman always asks her ME/CFS patients how many hours their feet are on the floor; i.e. how many hours of upright activity, whether sitting or standing, they can maintain. If that could be measured, we would finally have an objective measure of one of the IOM criteria: fatigue as it affects functioning. They are collaborating on a grant proposal with the idea of using this as an objective measure of physical functioning in a clinical trial. That’s the kind of thing we need to get pharma interested in this disease.

Diagnostic Algorithm

The BHC is working with the Clinical and Translational Science Awards (CTSA) program at the NIH to create a diagnostic algorithm. CTSA’s goal is to find ways to get treatments to patients faster.

The BHC seeks to create a diagnostic algorthim which allows doctors to diagnose ME/CFS patients in just four steps using an in-office assessment. Getting this into doctors’ offices would: a) help bring doctors up to speed; b) help out patients; and c) greatly increase the pool of ME/CFS patients who could support efforts to get ME/CFS more resources. The bigger this patient community is, the better shot we have at ending this disease.

Genetic Study

The genetic database at the University of Utah is one of the largest and most comprehensive in the world.

The BHC is working with Ken Smith, Director of one of the world’s richest sources of genetic information – the Utah population database at the University of Utah. (That database was the source of more than 50 published studies last year.) That work – which involves 1,200 ME/CFS

Thank you, Cort. And a big thanks for these brave doctors who put their reputations and careers on the line for CFS!

Yes, Jeanie, deep thanks, as you say!

I believe we’ll see a breakthrough in 2019 because of all of the collaboration and technologies. I also love the “feet on the floor” concept, so simple, yet it sums it up really well. I have a desk job for six hours a day, M-F, but collapse when I get home. Thank you Cort and Merry Christmas!

Thanks Gail and Merry Christmas to you 🙂

Ditto!

Wow what fine people we have on our case.

Such clear thinking to get at the heart of the matter.

Thankyou everyone for yr passion and intelligence not to mention Cort the great communicator.

Isn’t it good to know that we have people with such passion and vision working on ME/CFS. It gives me hope 🙂

“Dr. Bateman always asks her ME/CFS patients how many hours their feet are on the floor; i.e. how many hours of upright activity, whether sitting or standing, they can maintain. If that could be measured, we would finally have an objective measure of one of the IOM criteria: fatigue as it affects functioning.”

Technically that shouldn’t be that challenging. A smartphone can be transformed into a level (device measuring if something is flat) with nothing but an app. That should be sufficient to measure if something is sufficiently perpendicular to the ground. Attach that to the calf and write an app logging it 24/7. Colledge students with appropriate skills should be able to do it.

The bigger challenge is to make it more comfortable to ME/FM patients and increase battery life so no or very few battery recharging needs to be done. That can be done by replacing the smartphone with a custom made design that only has the essential components: sensor, small low power microprosessor, some storage and a small battery. Then find an easy way to wear it like a well designed hollow sleeve to put around stockings and some padding to decrease pressure and pain from the components.

That should be mainly a matter of funding, finding the wright people/institutions to do it and find a collaboration type that allows it to be done in a lean, fast end flexible way.

I’m a little confused on that part of the article too.

Is the challenge to acquire/design a device that can automatically log the time a person spends vertical? Or is it to see if time spent vertical is a good proxy for functional impairment? They both seem like major challenges.

Cort, could you elaborate if you know?

I’m a programmer and I play with electronics in my spare time. And I could build a prototype of something like this for $50-$75 in parts. But getting something built to meet consumer expectations for size, quality, ease of use, reliability, etc. Would be a major undertaking. That Fitbit on your wrist has millions dollars of R&D, manufacturing, infrastructure, service, support, etc. behind it.

Hi Blaine, I really don’t know much about it. Like you its piqued the interest of a biomechanical engineer at the University of Utah. If you have some ideas or could help maybe you could contact BHC.

Thanks, Cort. I appreciate it.

Hi Blaine,

reading the second part Cort wrote on the BHC I read “They now have 7 providers: 4 MD’s, 2 physician assistants (PA’s) and one registered nurse.” That is in the BHC.

It seems they have currently no personnel with a technical background. Maybe they have difficulties with estimating what can be done in what kind of budget and time frame.

@Cort: If they would have no technical trained personnel then rather then us individuals contacting them it could be helpful (for you) to ask if they would be helped by some sort of “blog like discussion” between them and technical skilled patients and healthy volunteers to aid them with the sensor part to write a good grant application.

I think going for a grant application is still the road to go as we need the NIH to see good grant applications to come in, but having a solid technical part of the grant application increases chances of approval, chances of success (and with it credits to get succeeding grant applications approved) and value of the sensor product.

The Fibromyalgia Treatment Center in Marina Del Rey, California is also a non-profit educational outreach center for patients with CFS/ME and FM working with the research center The City of Hope.

I had no idea. Thanks for putting that out there 🙂 I hope to learn more. If you have any more information please feel free to contact me. I love hearing about efforts like this 🙂

Alot going on, thanks Cort. Love hearing news of more work I didn’t know about

Thanks Eimear,

I was VERY impressed with the BHC.. It was a nice surprise for me too. Stay tuned for part II. 🙂

Hi Cort

A web search indicates that Precise.ly is no more. Service suspended though outstanding results are still available 🙁 see https://help.ouraring.com/troubleshooting/connecting-with-precisely