At one time ME/CFS was called “chronic EBV disease”

The Epstein-Barr virus has been a virus of interest since almost day one in chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS). In fact, at one point, EBV was such a hot topic that ME/CFS was called for a time “chronic Epstein-Barr virus disease”

While studies have generally failed to find evidence of EBV reactivation, EBV has never fallen out of the picture with ME/CFS, and for good reason. For one, it’s possible that researchers were looking in the wrong place (the blood) to determine if EBV is an issue in this disease.

For another, EBV infection in adolescence or later and the infectious mononucleosis (glandular fever) it produces, is a common trigger in ME/CFS, and is a proven risk factor for multiple sclerosis. Besides ME/CFS, researchers are continuing to assess the role EBV may play in many serious illnesses including multiple sclerosis (MS), systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), Guillain-Barre Syndrome, several cancers, rheumatoid arthritis (RA), juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA), inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), celiac disease, schizophrenia, and others.

Neuroinflammation, of course, is a hot, hot (pun intended) topic in both ME/CFS and fibromyalgia. Recent studies suggest neuroinflammation is present in both diseases and major studies are underway to assess that finding. Nobody until now, though has attempted to complete the circle, and bring that “original gangster” in ME/CFS – Epstein Barr Virus – and the new guy in town – neuroinflammation – together. Could EBV be causing or contributing to the neuroinflammation present in the disease? Some Ohio State researchers think so.

Some History

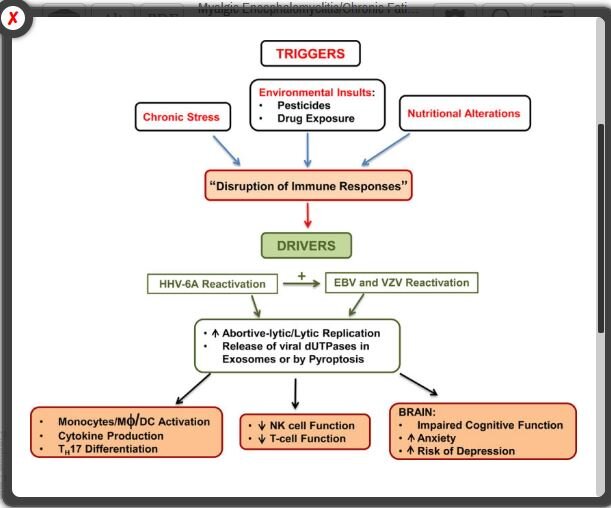

Over 10 years of work by an Ohio State University team led by Maria Ariza and Marshall Williams has been turning the EBV question in ME/CFS on its head. High levels of EBV, they believe, are not the problem in ME/CFS at all. In fact, their studies suggest that EBV may be at its most dangerous in ME/CFS not when it reactivates – but when it fails to reactivate properly.

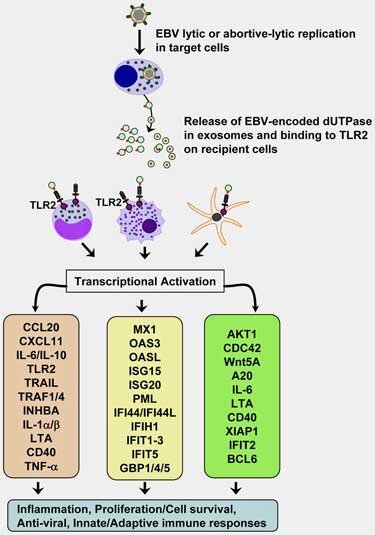

They’ve found that long before the bug has fully reactivated it’s already produced a potentially pathogenic protein called dUTPase. With the NIH supporting them every step of the way – their continuing grant on dUTPase is now in its 9th year – the evidence that this protein is contributing to ME/CFS (and other diseases) has continued to build.

In 2012, the group found evidence that the immune systems of people in a large subset of ME/CFS patients were indeed battling this protein. Just a year later they showed that even when viral loads of EBV were low, dUTPase was still triggering a significant pro-inflammatory response. That finding suggested that prior attempts to link EBV viral loads to ME/CFS were barking up the wrong tree.

Two years later, they demonstrated that dUTPase was able to make its way into exosomes (now a major topic of interest in ME/CFS), cross the blood-brain barrier, produce major immune effects, and perhaps even promote further EBV infections.

Then a 2017 study added another herpesvirus long suspected in ME/CFS – HHV-6 – to the mix when it found antibodies to both EBV and HHV-6 dUTPases in almost fifty percent of ME/CFS patients. That suggested that the two herpesviruses might even be reactivating each other – a feature found in some very immune-suppressed states.

Autoimmunity Too?

Then again, really significant immune suppression in ME/CFS may not be a surprise. Up to 75% of ME/CFS patients had reduced levels of the B-cells designed to keep EBV in check. If that wasn’t enough, in 2017 the first evidence of an autoimmune process involving EBV dUTPase was found in ME/CFS. Autoantibodies to the human dUTPases (humans produce a dUTPase as well) were found in ME/CFS – occurred in much higher levels than in healthy controls (39% vs. 5%). That suggested that the immune response to EBV and HHV-6 dUTPase may have gone awry in some people with ME/CFS – and their bodies were now attacking their own human dUTPase (ouch!)

And Neuroinflammation?

In the present study we provide further evidence…. (that) dUTPase protein…could contribute to the development of a neuroinflammatory microenvironment in the brain(s) (of a subset of ME/CFS patients.) The authors

An earlier study had shown that the EBV dUTPase protein could be causing or contributing to the symptoms present in ME/CFS. Since many of these symptoms can be produced by the brain, in “In the 2019 study “Epstein-Barr Virus dUTPase Induces Neuroinflammatory Mediators: Implications for Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome.“ Williams and Ariza next asked if the enzyme could be affecting the integrity of the blood-brain barrier (BBB) and other aspects of neuroinflammation.

There’s a pretty good reason to believe this might be the case. EBV, after all, has been associated with some pretty nasty neurological diseases. The virus loves to hang out in the nerve cells, is a risk factor for M.S., and has, in fact, been found scattered throughout the astrocytes and microglial cells in MS patients’ brains.

To test their hypothesis, the Ohio State University researchers plopped the dUTPase protein into a variety of cells and then determined how it affected the expression of genes that play an important role in maintaining the blood-brain barrier (BBB) as well the functioning of various brain cells (cerebral microvascular endothelial cells, astrocytes, microglia cells).

The dUTPase protein turned out to be quite adept at tweaking genes and proteins associated with the BBB and neuroinflammation. It turned on 12 of 15 genes and 32 of the 100 proteins examined in vitro (in the lab) and 34 of the 84 genes examined in mice. As EBV dUTPase was down-regulating the expression of genes dedicated to producing a tight BBB it was “strongly” inducing the expression of two cytokines (IL-6 and IL-1β) known to disrupt The BBB. The fact that these genes also play a role in the production of fatigue, and in nerves associated with pain production, as well as tryptophan, dopamine, and serotonin metabolism, suggested that this enzyme, in or out of the brain, could conceivably be causing widespread problems.

If EBV dUTPase gets inside the brain, it seems almost guaranteed to cause neuroinflammation. Studies indicate it can trigger microglial cells and astrocytes (star-shaped immune cells in the brain) to produce potent pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-6, IL-1β, and TNF-α). It also prompts astrocytes to produce a substance (PTGS2/COX-2) associated with neuroinflammatory toxicity. Plus it’s able to alter the expression of genes associated with pain (GPR8451 and GCH152) and fatigue (TBC1D153). In mice, it altered the expression of genes associated with cognition (synaptic plasticity, learning, and memory).

One of the more intriguing findings, given the possible disruption of the kynurenine pathway in ME/CFS, was the protein’s potential to increase the synthesis of a potent neurotoxin called quinolinic acid. Genes associated with the metabolism of two of the major neurotransmitters in the brain, dopamine, and serotonin, were also affected.

All in all, EBV dUTPase is clearly not a protein anyone wants hanging out in their brain. While this study demonstrated that the protein appears to have the capability to make its way to ME/CFS patients’ brains, determining if it has actually done that will take more study.

While the protein and its antibodies (or the autoantibodies to the human dUTPase) are not found in everyone with ME/CFS, the potential subset it is found in (30% to 60%) is pretty darn large. Plus, the virus is heavily implicated in the stress response. If you feel like your nervous system is overreacting to, well, anything (or everything), EBV and this protein could be a factor.

Of all the viruses, EBV and the other herpesviruses are most apt to come out and play when one’s system is stressed. In fact, Ron Glaser, one of the initiators of the EBV dUTPase research effort, demonstrated back in 1991 that EBV thrives in situations of psychological stress. Given the enormous stress people with ME/CFS are under, and the effects the illness has on both axes of the stress response, it makes sense that this virus might be continually trying to reactivate – and could be spilling it’s toxic protein into the bloodstreams of many people with this disease.

A Good-bye to a Pioneer

His memorials mention his impact on the psychoneuroimmunological (PNI) field, his enthusiasm, (and the red and white Corvette he loved). What they don’t mention is that this major figure also devoted much time to a neglected field called chronic fatigue syndrome.

Glaser, in fact, took the time out of his busy schedule to sit on the now-disbanded federal advisory committee for ME/CFS (CFSAC). He was not a man to mince words. An accomplished researcher with a long history of grant success, Glaser was first shocked, and then angry at the rejections piling up for his ME/CFS grant applications. He just couldn’t understand it. Never in his decades of work had he experienced such a thing.

Stating, ironically, he couldn’t stand the stress (he did look like he was about to burst a blood vessel), he eventually moved on, but not before making his experiences perfectly clear to the federal advisory committee and everyone around him. Glaser was not happy at not being able to work more in ME/CFS, but the work he did did not go for naught. Glaser first published on EBV dUTPase in 1985 and on EBV and ME/CFS in 1988 and his work lives on in Ariza and William’s studies on ME/CFS today. Check out a memorium to Ron here.

Marshall Williams – On the Continuing Hunt for EBV dUTPase in ME/CFS

I asked Marshall Williams about his work with EBV and ME/CFS.

What about the connection between this protein and the presence of infectious mononucleosis/glandular fever in ME/CFS? Do we have any idea if the enzyme is more likely to be found in people whose disease was triggered by IM or who had an acute, flu-like onset?

That is an excellent question. We are in the process of trying to obtain longitudinal serum samples from an IM cohort who developed CFS as well as age-matched patients who had IM but never developed CFS. Hopefully, that may address this question.

Not really at this point but maybe in the future. Screening CSF from ME/CFS patients for antibodies to the EBV-dUTPase or HHV-6 dUTPase might suggest potentially the presence of these viruses in the brain.

Exosome research is heating up in ME/CFS. Some anecdotal reports show that exosomes in the blood may be affecting energy metabolism and other functions. Could herpesvirus dUTPases be involved? Is there any more information on exosomes and EBV dUTPases?

We have not looked at energy metabolism but there are some reports in the literature that some herpesviruses including EBV and HHV-6 alter mitochondrial function. There is information concerning EBV products in exosomes but most of these have focused on proteins/microRNAs involved with latency.

What is next for your team?

We are in the process of submitting a manuscript detailing a mechanism(s) by which the EBV-dUTPase and to a lesser extent the HHV-6 dUTPase alter germinal center function, which could contribute to autoimmunity in CFS patients. We will be continuing these studies as well as those regarding neuroinflammation. (B-cells manufacture autoantibodies in the germinal centers found in the lymph nodes and spleen)

I found this text on the French website “Doctissimo”. Would the eradication of the Epstein-Barr virus cure MS/CFS?

In an article published in the journal Science Advances, researchers from the University of Illinois at Chicago (USA) reveal the results of their study on a drug that could prevent the Herpes simplex 1 and Herpes simplex 2 viruses not only from reproducing, but also to eliminate it completely.

The drug tested in this study is an active substance with antiviral action already prescribed as part of a deficiency of a rare enzyme: phenylbutyrate.

• Initially, the researchers observed that on human skin and cornea samples, phenylbutyrate alone could eliminate both the virus and the currently proposed treatment acyclovir.

• Then, in a second step: they noted that when phenylbutyrate is administered in addition to acyclovir, it allows the virus cells to be completely cleaned so as to avoid the risk of recurrence.

When the herpes virus enters the body, it ‘hacks’ cells to make viral proteins that allow it to reproduce. But during the study, the researchers noted that phenylbutyrate combined with aciclovir, the treatment already prescribed for type 1 herpes, prevented this hijacking and thus prevented the herpes virus from multiplying in the body again. “This process allows the cells to function properly and force them to concentrate on cleaning up the virus,” says one of the researchers, Tejabhiram Yadavalli.

PLEASE let me know if and when any studies are in the near future. I have struggled forever it seems with ebv, fibromyalgia, systemic lupus- (had mono the first time, when i was 11) I live in Stanislaus County, Ca.

Thank you.

Sincerely,

Abby