In the second part of Dominic’s series on the neuroendocrine dysfunctions found in prolonged critical illness states and ME/CFS/FM he explores treatment options, and asks if returning the neuroendocrine system normality will require new treatment combinations.

Section 2: Treatment

- Treatments with peripheral hormones

- Supplementing thyroid hormones in critical illness

- Supplementing thyroid hormones in ME/CFS and fibromyalgia

- Supplementing GH and IGF-1 in critical illness

- Supplementing GH and IGF-1 in ME/CFS and fibromyalgia

- Treatments with glucocorticoids in critical illness

- Supplementing with glucocorticoids in ME/CFS and fibromyalgia

- Treatments targeting the hypothalamus and pituitary

- Combination trials to reactivate secretion by the pituitary in prolonged critical illness

- Trials to reactivate GH secretion by the pituitary in fibromyalgia

- Reactivation of the HPA axis with corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH)

- Hypothetical interventions to reset the HPA axis in ME/CFS (“bi-stability model”)

- Other treatments

- Traditional medicines

- Immune system modulation and anti-oxidants in prolonged critical illness

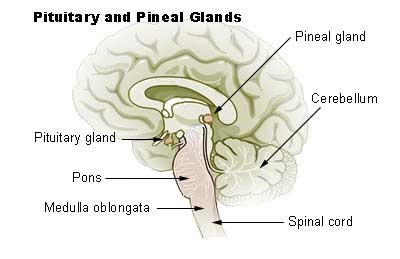

Promising results from critical illness research suggests that treatments targeting the hypothalamus and pituitary could restore normal metabolism. (Pituitary gland)

Researchers have tried to reverse neuroendocrine dysfunctions in prolonged critical ill patients, with the hope of reducing muscle wasting and mortality and aid overy. Similarly, researchers and clinicians have tried to remedy the depressed hormone status in ME/CFS.

The treatments largely differ depending on which neuroendocrine axes, and what parts of the neuroendocrine axes are being targeted. Many treatments involve supplementing depressed hormone levels directly, including thyroid hormone, IGF-1 and GH, and adrenal hormones (sub-section A). Other treatments target the dysfunction at the “central” level — i.e. the hypothalamus and/or the pituitary (sub-section B).

A. Treatments with peripheral hormones

The use of thyroid hormones, glucocorticoids (cortisol) and even GH and IGF-1 has a long history in medicine. They are mostly used to treat hypothyroidism, inflammation and growth failure, respectively. However, they have also been trialed and used to treat prolonged critical illness, ME/CFS and fibromyalgia.

Supplementing thyroid hormones in critical illness

Given the depressed levels of thyroid hormone activity found in critical illness, clinicians began, in the late 1970s, to suggest thyroid hormone supplementation in an attempt to increase survival rates (Carter et al., 1977; Brent et al., 1986 and DeGroot, 1999). This approach continues to be debated today (Davis, 2008; Kaptein et al., 2010; De Groot, 2015; Moura Neto et al., 2016; Breitzig et al. 2018). Results with thyroid supplementation have been mixed (see reviews in Farwell, 2008, and Fliers et al., 2015) but the dosage, type of supplement, and timing of treatment initiation could explain the discrepancy in outcomes (van den Berghe, 2014; van den Berghe, 2016).

Given the impaired conversion of T4 to T3 in prolonged critical illness, some researchers suggest using T3 supplementation (as opposed to T4 supplementation) (Biondi, 2014). Moreover, tests on rabbits have shown that thyroid hormone supplementation doses have to be higher than what the body naturally produces (i.e. supra-physiological) to achieve results (Debaveye, 2008). Many publications simply conclude that more studies on the effects of thyroid hormone supplementation in critical illness are required (Mancini et al., 2016).

Supplementing thyroid hormones in ME/CFS and fibromyalgia

Many stories exist of CFS/ME or fibromyalgia patients recovering by using thyroid hormones, particularly T3. I’ve listed some of the evidence and the approaches ME/CFS practitioners have used in my previous blog post. These approaches vary in the type of thyroid hormones (natural desiccated thyroid, synthetic T3 or T4, etc.), the dosage (supra-physiological vs. physiological), the complementary vitamin / mineral supplements, etc.

Several practitioners emphasize the importance of providing adrenal hormones in tandem with thyroid hormones to enable the body to cope with an increase in metabolic rate. In the absence of a standard protocol, patients are discussing these treatment variations in a plethora of online discussion forums.

I wonder why the supplementation of T3 can seemingly reverse uniform neuroendocrine suppression over several endocrine axes. Perhaps this is due to T3’s role in mediating the immune system (DeVito et al., 2011; Jara et al., 2017; Van der Spek et al., 2018) and the interactions between endocrine axes (see Annex).

Supplementing GH and IGF-1 in critical illness

The hormone IGF-1 has been tested and applied in critical illness for decades, with positive results in reducing catabolism (i.e. muscle and protein loss), recovery of gut mucosal function, tissue repair, control over inflammatory cytokines, decreased protein oxidation and increased glucose oxidation, etc. However, doses must be physiological (i.e. not higher than regularly produced by the body) in order to avoid side effects (see review by Elijah et al., 2011).

Some positive results have also occurred with administration of GH (or a synthetic version called rhGH) (reviews by Weekers and van den Berghe, 2004; and Elijah et al., 2011). However, a large scale double-blind randomized control study of rhGH infusions undertaken in 1999 resulted in increased mortality of patients (Takala et al., 1999). This led to the near cessation of the use of GH or rhGH in critical care. Since then other researchers have argued that that dosages were too high, thereby overwhelming the negative feedback loops (Weekers and van den Berghe, 2004).

Finally, some promising trials have also been done combining the administration of GH and IGF-1 in critical illness (Teng Chung and Hinds, 2006; Hammarqvist et al., 2010). Again, GH and IGF-1 have complementary roles in the balance between anabolic and catabolic activities.

Supplementing GH and IGF-1 in ME/CFS and fibromyalgia

A series of placebo-controlled studies demonstrated that GH injections over several months — in the form of physiological doses or doses adapted to increase IGF-1 to a specific level — reduced pain and improved quality of life scores in fibromyalgia patients in a number of studies (Bennett et al., 1998; Moorkens et al. 1998; Cuatrecasas et al., 2007; Cuatrecasas et al., 2012; and Cuatrecasas et al., 2014).

Treatments with glucocorticoids in critical illness

When clinicians determine that cortisol levels are low relative to the severity of the illness administration of large daily doses of hydrocortisone (200 – 300 mg) in patients during critical illness is quite common (see “critical illness-related corticosteroid insufficiency,” CIRCI) (Marik et al., 2007; Gheorghiță et al., 2015). Some researchers, however, argue that these high doses may be counterproductive because they further drive the negative feedback loop, resulting in “central” suppression of the axes (Teblick et al., 2019). Moreover, especially if administered for too long, large hydrocortisone doses heighten catabolic effects (see review in Boonen and van den Berghe, 2014a & 2014b).

Supplementing with glucocorticoids in ME/CFS and fibromyalgia

Cortisol (hydrocortisone)

Several studies have documented that a low dose of hydrocortisone can benefit ME/CFS patients, notably reducing fatigue and disability scores (see reviews in Holtorf, 2008; and Tomas et al. 2013). Daily doses of 5 – 15 mg of hydrocortisone also apparently don’t suppress the HPA axis further (Demitrack et al., 1991; Cleare et al., 1999) and may even improve the otherwise “blunted” responses of the pituitary to the signal from the hypothalamus, i.e. to CRH (Cleare et al., 2001).

Researchers have also documented that somewhat higher doses of hydrocortisone (25 – 35 mg per day) lead to a moderate decrease in endogenous ACTH and cortisol production in chronic fatigue patients, via the negative feedback loop (Demitrack et al., 1991; McKenzie et al., 1998).

Combination of hormones

Given the complementarity of hormones and interactions between neuroendocrine axes, better results have often been achieved by giving several peripheral hormones at once. For example, a number of trials have indicated that adding GH and/or IGF-1 avoids the catabolism effects, such as protein wasting and osteoporosis, linked to high dose glucocorticoid treatments (Giustina et al., 1995; Oehri et al. 1996). Similarly, some ME/CFS practitioners prescribe a combination of hormones, including thyroid hormones, adrenal hormones and even gonadal hormones (c.f. Holtorf clinic; Teitelbaum 2007).

B. Treatments targeting the hypothalamus and pituitary

A number of critical illness researchers argue that instead of administering peripheral hormones, treatments should target the “central” level (i.e. the hypothalamus and pituitary). They have 3 main arguments:

- it has been shown that the neuroendocrine suppression during prolonged illness largely originates at the level of the hypothalamus (i.e. the hypothalamus is not sending the required signals to the pituitary);

- the pituitary and peripheral endocrine glands are, in fact, undamaged, and could operate normally if given the right signals (with perhaps the exception of the adrenals that experience atrophy).

- by targeting the process at the central level, the rest of the neuroendocrine axes are unaltered — specifically, the negative feedback loops and adaptive peripheral metabolism of hormones remain intact, thus preventing the risk of toxic over-dosages (van den Berghe, 2016).

In sum: These researchers argue that treatments targeting the hypothalamus and/or pituitary may be more effective and safer than administration of the peripheral active hormones. I will describe some of these treatment trials below.

Combination trials to reactivate secretion by the pituitary in prolonged critical illness

A short, experimental trial of combination treatments in critically ill patients revived their HPA axis (from Murgatroyd-C-and-Spengler-D-2011-Epigenetics-of-early-child-development.-Front.-Psychiatry.)

Van den Berghe and her team performed a series of fascinating treatment trials with critical ill patients who’d been in the intensive care units for several weeks. The various combinations of factors they used to stimulate the pituitary attempted to substitute for the signals which in normal conditions are produced largely by the hypothalamus (van den Berghe et al. 1998; van den Berghe et al. 1999; Van den Berghe et al. 2001; Van den Berghe et al., 2002).

Specifically, they administered combinations of TRH (which stimulates the pituitary to produce TSH, in turn stimulating the thyroid gland), GHRH (which stimulates the pituitary to produce GH), GHRP-2 (an artificial gherlin-like peptide which also stimulates the pituitary to produce GH), and GnRH (which stimulates the pituitary to produce LH and FSH, in turn stimulating the gonads). (See Table 3). Three major findings were produced.

FIrst, they showed that each of these factors can reactivate the secretion of the pituitary for the relevant neuroendocrine axis, while keeping the negative feedback loops on the pituitary intact, thus preventing overstimulation of the endocrine glands:

- The administration of GHRH or GHRP-2 reactivated the pulsatile secretion of GH by the pituitary, and the plasma concentrations of IGF-1 and IGFBP-3 increased. Interestingly, GHRP-2 had a much stronger effect than GHRH, suggesting that the inactivity of gherlin likely plays a key role in prolonged critical illness (van den Berghe, 2016).

- Similarly, when the team administered TRH, the pulsatile secretion of TSH by the pituitary was reactivated, and the plasma concentrations of the peripheral hormones T4 and T3 increased. However, reverse T3 (RT3) also increased. This is problematic because RT3 blocks thyroid hormone receptors at cell levels, contributing to low thyroid hormone activity (see my first and second blog posts).

- Likewise, the administration of GnRH to prolonged critically ill men increased pulsatile LH secretion by the pituitary.

Second, the team showed that when prolonged critically ill patients were treated with a combination of factors to normalize GH and TSH secretion by the pituitary (i.e GHRH or GHRP-2 in combination with TRH), reverse T3 did not increase! This suggests that the normalization of the HPS axis is necessary for inhibiting the production of the problematic RT3. The authors write: “coinfusing a GH secretagogue with TRH appeared to overcome the impaired peripheral conversion of thyroid hormones in the majority of critically ill patients.” This is likely because GH can deactivate the D3 enzyme which converts T4 into RT3 (Weekers and van de Berghe, 2004).

Finally, the team showed that the combination treatments immediately inhibited catabolism (i.e. tissue break-down) and promoted anabolism (i.e. tissue building), thus halting the muscle and fat wasting of patients with prolonged critical illness. This effect was absent when GHRP-2 was infused alone and strongest when GnRH was added to the mix in critically ill men (i.e. GHRP-2 + TRH + GnRH). The authors write:

Coadministration of GHRP-2, TRH and GnRH reactivated the GH, TSH and LH axes in prolonged critically ill men and evoked beneficial metabolic effects which were absent with GHRP-2 infusion alone and only partially present with GHRP-2 + TRH. These data underline the importance of correcting the multiple hormonal deficits in patients with prolonged critical illness to counteract the hypercatabolic state” (Van den Berghe et al., 2002).

I believe these results are potentially fascinating in terms of their relevance to ME/CFS and fibromyalgia. The treatments were only administered for 5 days for experimental purposes, and benefits ended a few days after the infusions were discontinued. The trials were never repeated, despite suggestions as late as 2016 that these successes should be further explored (van den Berhge, 2016).

Table 3: Treatment trials to reactivate the pituitary in prolonged critical illness (van den Berghe et al.)

| Target | Factors used to stimulate the pituitary | Results in prolonged critical illness |

| HPT Axis | TRH (which stimulates the pituitary to produce TSH, in turn stimulating the thyroid gland) | Reactivation of the HPT Axis

Normalized TSH secretion by pituitary Normalized T4 and T3 levels Increased RT3 |

| HPS Axis | GHRP-2 (artificial gherlin mimetic which stimulates the pituitary to produce GH) | Reactivation of the HPS Axis

Normalized GH secretion by pituitary Normalized IGF-1 and IGFBP-3 levels |

| GHRH (which stimulates the pituitary to produce GH) | Lower pituitary reactivation response than with GHRP-2 | |

| Combination

HPS + HPT Axes |

GHRP-2 + TRH | Reactivation of the HPS and HPT Axes

Normalized GH secretion by pituitary Normalized IGF-1 and IGFBP-3 levels Normalized TSH secretion by pituitary Normalized T4 and T3 levels RT3 levels do not increase! –> Inhibit catabolism and promote anabolism |

| Combination

HPS + HPT + HPG Axes |

GHRP-2 + TRH + GnRH (trialed with men) | Reactivation of the HPS, HPT and HPG Axes

As above and also normalized LH secretion by the pituitary -> Strongest beneficial metabolic effect |

Trials to reactivate GH secretion by the pituitary in fibromyalgia

Recognizing that the secretion of GH by the pituitary is controlled by both stimulating (GHRF) and inhibiting (GHIF) signals from the hypothalamus, researchers tried to treat fibromyalgia patients with pyridostigmine (Mestinon), a drug that inactivates the inhibiting effect of GHIF.

Pyridostigmine did reverse the impaired GH response to exercise in fibromyalgia patients (Paiva et al.; 2002), but did not improve fibromyalgia symptoms (Jones et al.; 2008). This is consistent with van den Berghe et al.’s findings that the anabolic effects of GH only occur in combination with adequate action of the thyroid hormones (see Table 3).

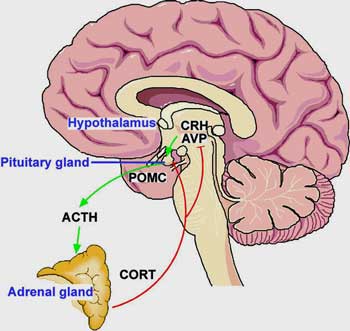

Reactivation of the HPA axis with corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH)

Complementary to the work of van den Berghe et al., researchers have suggested using CRH to reactivate the HPA axis in prolonged critical illness (Peeters et al., 2018a). (Recall that CRH is the signal from the hypothalamus that stimulates the pituitary to produce ACTH, in turn stimulating the adrenals).

These researchers argue that the suppressed HPA axis in prolonged critical illness (due to initial high levels of cortisol during the acute phase) is similar to the HPA axis suppression seen in patients on long-term glucocorticoid treatment. When the latter patients are withdrawn from their long-term treatment, clinicians apparently need to “reactivate” hypothalamic CRH secretion. The researchers thus suggest that providing CRH during critical illness could potentially allow the reactivation of ACTH synthesis by the pituitary, and thereby prevent the adrenal atrophy seen in the prolonged phase of the illness.

Hypothetical interventions to reset the HPA axis in ME/CFS (“bi-stability model”)

Recall the model describing ME/CFS patients as stuck in a “low-cortisol” HPA axis steady state .

Based on this model, researchers have proposed various fascinating interventions to move patients to the “normal-cortisol” HPA axis steady state.

Ben-Zavi et al. (2009) suggested that “a well-directed push given at the right moment may encourage the axis to reset under its own volition.” Specifically, they argue that artificially dropping cortisol levels even further than they already are in ME/CFS patients, should by taking advantage of the HPA axis’ negative feedback loop, increase ACTH secretion. According to their model, once ACTH levels exceed 30% of baseline levels, the HPA axis will naturally progress to the “normal-cortisol” HPA axis steady state and the treatment can be discontinued. I am not aware of any trials of this hypothesis.

Similarly, Sedghamiz et al. (2018) have suggested that an “externally applied stress” can serve to re-initiate proper HPA axis functioning. Specifically, this team has modeled the effect of blocking the glucocorticoid receptors (GRs). They argue that this intervention renders the low-cortisol “steady state” unstable – resulting in a return to the “normal-cortisol” steady state.

This is also basically the premise of the Cortene trials. I wonder whether — given the suppression of multiple neuroendocrine axes in ME/CFS — an intervention targeting just one axis will suffice. Perhaps, given the interactions between axes, the correction of the HPA axis might serve as a lever to also correct the other neuroendocrine axes.

Finally, based on the HPA bi-stability model, similar suggestions have been made for achieving remission from Gulf War Illness. Craddock et al. (2015) – who have included the immune system in their model – calculated that an initial inhibition of Th1 inflammatory cytokines (Th1Cyt), followed by a subsequent inhibition of GR function, would allow a robust return to a “normal-cortisol” steady state.

C. Other treatments

Given the many “central” and “peripheral” mechanisms modulating the function of the neuroendocrine axes — and the bi-directional relationship between the neuroendocrine axes and the immune system — many other potential forms of treatment for neuroendocrine dysfunctions exist. I list two further categories below.

Traditional medicines

Many traditional medicines may also help restore the function of the neuroendocrine axes, including Shilajit (a mineral rich plant deposit from India) and Myelophil (a mix of herbs from China) (Tomas et al., 2013).

In one experiment, researchers found that a combination of herbal extracts used in traditional chinese medicine to treat “Kidney Yang Deficiency Syndrome” attenuated the metabolic dysfunction induced by hydrocortisone injections in rats. Compared to controls, rats treated with the herbal extracts experienced less dysfunctions in energy metabolism, lipid metabolism, gut microbiota metabolism, biosynthesis of catecholamine (norepinephrine), and alanine metabolism (Zhao et al., 2013).

Immune system modulation and anti-oxidants in prolonged critical illness

See my previous blog: The Relevance of Research on Critical Illnesses for Chronic Fatigue Syndrome ME/CFS: A vicious cycle between cytokines, oxidative stress and thyroid hormones. Notably, recall that the thyroid hormone T3 also modulates the immune system.

Summary of Section 2: Trials to reverse neuroendocrine dysfunctions in prolonged critical illness and ME/CFS and fibromyalgia have a lot of similarities (see Table 4). Perhaps the most interesting lessons come from treatment combinations that target several neuroendocrine axes at once. These provide revelations about the interactions between the axes and have had important initial successes.

Table 4: Summary of treatments proposed and trialed to remedy neuroendocrine dysfunctions in ME/CFS and critical illness

| Neuroendocrine axes targeted | Treatments with peripheral hormones | Treatments targeting the hypothalamus and pituitary |

| HPT Axis (thyroid) | Prolonged critical illness:

Supplementation w/ thyroid hormones |

Prolonged critical illness: Administration of TRH to reactivate pituitary secretion of TSH |

| ME/CFS and fibromyalgia: Supplementation w/ thyroid hormones (natural desiccated thyroid, T4, T3). | ME/CFS and fibromyalgia: none?

|

|

| HPS Axis

(growth hormone) |

Prolonged critical illness:

Supplementation with GH and IGF-1

|

Prolonged critical illness: Administration of GHRH and GHRP-2 to reactivate pituitary secretion of GH |

| ME/CFS and fibromyalgia:

Supplementation with GH and IGF-1 |

ME/CFS and fibromyalgia: Drug to inactivate GH inhibiting hormone (GHIH) | |

| HPA Axis (adrenals) | Prolonged critical illness: High dose hydrocortisone

|

Prolonged critical illness: Administration of CRH to stimulate pituitary ACTH secretion (proposed) |

| ME/CFS and fibromyalgia:

Low dose hydrocortisone or other glucocorticoids |

ME/CFS and fibromyalgia:

– Blocking of central glucocorticoids receptors (GRs) (Cortene Trials) – Suppress cortisol levels to reactivate ACTH secretion (modelled) – Inhibition of Th1 cytokines followed by inhibition of GRs (modelled for Gulf War Illness) |

|

| HPG Axis (gonads) | Prolonged critical illness: none? | Prolonged critical illness: Administration of GnRH to stimulate pituitary release of LH (in men) |

| ME/CFS and fibromyalgia: as part of combined treatments (below) | ME/CFS and fibromyalgia: none? | |

| Combination of axes

|

Prolonged critical illness: GH and IGF-1 in addition to hydrocortisone | Prolonged critical illness: TRH + GHRP-2 + GnRH (see Table 3. above). |

| ME/CFS and fibromyalgia:

Thyroid hormone + adrenal hormones (+ gonadal hormones) |

ME/CFS and fibromyalgia: none? |

Conclusion

Irrespective of the nature of the original illness or trauma, multiple neuroendocrine axes are suppressed in the prolonged phase of critical illness, Similar patterns of neuroendocrine suppression have also been observed in ME/CFS and fibromyalgia.

The last decades have seen substantial advances in researchers’ understanding of the various “central” and “peripheral” mechanisms underlying critical illness, and the role cytokines and O&NS play in the persistence of neuroendocrine suppression during prolonged critical illness. These can undoubtedly inform our understanding of ME/CFS and fibromyalgia.

Similarly, the findings from ME/CFS and fibromyalgia specifically relating to the dysfunctions at the mitochondrial level — which are associated with the neuroendocrine alterations, inflammatory cytokines and O&NS — may be able to provide important complementary insights into critical illness. The sharing of knowledge and collaborations in these fields would likely serve to complete our understanding of both conditions.

Finally, a combined analysis of the treatments already tried for either prolonged critical illness or for ME/CFS might help identify potential approaches that could be trialed for one or the other of these conditions. The “millions missing” from ME/CFS, as well as the individuals hanging on for their lives in critical care units around the world, might find relief through treatment approaches that leverage the similarities between their conditions.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

The Low T3 Series on Health Rising

- The Atypical Thyroid Issues in Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS), Plus a New Thyroid Subset?

- Pure T3 Thyroid and Stories of Recovery from Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS) and Fibromyalgia: An Overview.

The Critical Illness Series On Health Rising

- Neither dying, nor recovering”: Learning from ICUs to Solve ME/CFS and Fibromyalgia – A Synopsis (Nov. 2019)

Notes

References

It is worth investigating one’s levels of thyroid, cortisol and growth hormone. That being said, even bringing all of them in range with replacement hormones may not improve the ME/CFS symptoms. That was my case. I had the classic low T4, TSH, T3 and elevated reverse T3. Armour or

Naturethroid eventually brought them in range but still didn’t improve ME/CFS. At first I had adrenal fatigue, which is easily provable by running multiple 4 part saliva tests. You can order them yourself with no

Dr needed through CanaryClub online. But as time went by my cortisol levels were SO low as to be dangerous. I can’t tolerate generics such as Cortef so I get a more natural HC from a Compounding pharmacy. It’s grown on soy or yam. Over time I went on full replacement HC (hydrocortisone) and CT scans showed

my adrenals are ‘shriveled’ up. At this point I basically am described as having ‘terciary Addisons’. My

GH levels have remained normal. Being 65, I’m also on bio identical hormones. Still… not a whit of improvement in my ME/CFS. When my

HC or Thyroid is low I feel markedly

worse but even well in range I don’t feel ‘better’ .

Stephanie, I have had a similar experience, except that I didn’t go on hydrocortisone on a regular basis (just for pain relief, and it was the best, when I had “slipped discs” and shingles. On low dose steroids, I had a panoply of emotional side effects that my doctor recognized as steroid related; on the higher dose, for some reason, that didn’t happen. I take a host of replacement hormones and my blood levels, and thyroid size, are normal, but I don’t feel any better. Have thought of just easing off them and seeing if it makes any difference.

Even if you don’t actually ‘feel’ better, if your thyroid and hormone levels are low it’s beneficial to take them and have them in range for many, many reasons. They help the body in so many ways. I seem to tolerate Armour, or Nature-Throid or Erfa but not any synthetics since most of them are just T4 and I don’t convert T4 to T3 well. For me, I also saw a big improvement in my osteoporosis when I began using bio identical hormones and DHEA. Many ME/CFS sufferers have a hard time tolerating HC as well. It’s a delicate balancing act. I finally began having the Compounding pharmacist put the natural HC in hypromelos powder to make it timed release. I don’t know about you, but I sometimes feel positively

Schizophrenic (LOL) following all the ‘progress’ on ME/CFS research. Yay…they are finding out new stuff…hmmm…will they ever figure this out… will it be in my life time…I live in rural Texas and can’t even find a decent, progressive PCP. Good luck finding one that would

do the protocol and I can no longer travel. So making the best of it, finding joy in the moment is the order of the day. Some days

do-able…some days I feel like a cranky old crone!

I’ve had a thyroidectomy and being on WP Thyroid 65mg twice a day. I feel worse than ever. ME/CFS is so bad now. I was diagnosed in1999 with fibromyalgia I could work through the fatigue before having my thyroid removed. I’ve had head injury over the years, this makes me wonder it the head injuries is what this this cycle of hormone imbalance on.

Maybe Armour would work better for you. When I was first diagnosed with Hashimoto’s, my doctor and I went through several formulas before settling on Armour. There’s a synthetic version of it, but my endocrinologist prefers I take the natural Armour. Hashimoto’s is certainly different from having to have full thyroid replacement, but maybe the Armour is worth a try, if you haven’t already tried it. People have such different individual reactions.

I understand these ideas to be aligned with Cortene’s hypothesis, but can someone with more knowledge on the topic explain the link to the metabolic trap hypothesis?

Both Cortene’s hypothesis and the metabolic trap hypothesis end up in increased serotonergic production in the same part of the brain (!).

It was wild to see two hypotheses pop up almost at the same time which went to the same part of the brain and involved the same end result – neither which had been proposed before!

Thanks for the explanation Cort. In my head I’m still trying to figure out what’s downstream of what. (Would Cortene just be solving a downstream effect of the metabolic trap?) But maybe that’s the question on everyone’s mind.

Back in 2010 some of us POTS people talking about possibility of high serotonin. Some were finding it.

Personally, feel high glutamate and dopamine issues may be a bigger issue. Dr. Jerod Younger doing research on glutamate now.

My Question, is there any trustworthy doctors in Australia or New Zealand or in the Southern Hemisphere who prescribe any of these therapies? I’m especially interested in the hypothyroid one T3?

Thank you

By the way I’ve had a reasonable improvement on the antihistamines fexofenadine with Loratadine, and the anti inflammatory Ibuprofen, preferably taken before exertion or immediately after. I’m on LDN but it had little effect until I tried the antihistamines

Hi Brendan. Have you heard of Ros Vallings in Auckland, NZ? She is the only specialist ME/CFS doctor I know of in New Zealand. Come to think of it I would probably be wise to travel to see her myself. Not sure about trusted medical care in Australia? Thanks for the information Dominic. It is a bit disconcerting to contemplate just how “stuck” we might be.

I just read that “as we age the Blood Brain Barrier becomes more permeable”

No wonder we can’t take things like before and things bother us now that didn’t in the past.

Research shows old age and drugs open the BBB allowing core blood to enter the brain causing plaque to form which kills brain cells-we call this Alzheimer’s.We have an epidemic of this disease and we use 75% of world drugs,lifespans of men and young,poor single white women are declining.They say this will bankrupt our medical system as many new drugs have been tried and none work.I feel drugs do not work as they are the cause.

LIGHT CONTROLS OUR HORMONES

PERIOD

I think this is a very interesting and complex area. I have had my thyroid and other parts of my body investigated and nothing really accounts for my health issues.

However, as I’ve mentioned in other comments, I made improvements by listening/watching Dan Neuffer’s videos and recovery videos and then making some everyday changes, which helped unhook me from being persistently wired.

I then slept more deeply/restoratively and as a consequence could eat more food, without a reaction.

His theory is based around the autonomic nervous system dysfunction. He discusses his view of the HPA axis.

Dan has videos entitled The Root Cause of ME/CFS, Fibromyalgia and Pots.

Another person who discusses the HPA axis is Dr David Mickel. He has an interesting video on YouTube called Symptoms of Chronic Fatigue/ME and Fibromyalgia Explained Dec 13 2007.

Before I experienced the improvement in my health I couldn’t see how these theories would help. However, I was desperate as I could only tolerate an extremely limited range of food. So I gave Dan Neuffer’s ideas a go and much to my surprise and relief they worked.

I continue to sleep better.

Might be worth a look…

If Ghrelin stimulates both growth hormone and dopamine production, then are our changed eating and living conditions an important part of disregulating our hormone system?

Ghrelin is also called the hunger hormone. In the western world food is widely available. That plus many people doing office jobs rather then physical work should have a strong influence on ghrelin levels compared to their medieval values. Would that alone be sufficient to help disregulate much of our hormone housekeeping? Would that be part of why some patients experience improvements with intermittent fasting and ketogenic diets?