“It’ll be a tremendously enormous data set” NIH official

It’s rough reading about just how good exercise is for you – particularly for those of us who loved to exercise pre-ME/CFS. Exercise in most people improves the working of just about every system in the body. Stop exercising regularly and your risk for many different kinds of cancer, heart disease, Alzheimer’s disease, osteoporosis and early death rises. The misery conditions – pain, depression, anxiety, poor cognition – they all increase when we don’t or can’t exercise.

Huge Study

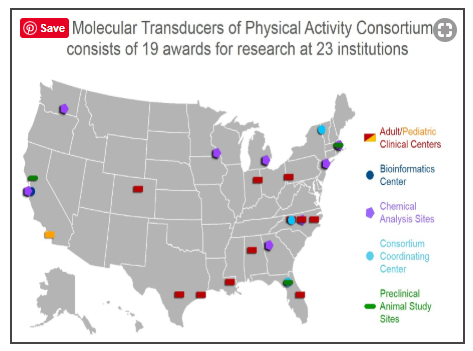

That’s why the NIH is pouring almost $170 million (yes, $170 million!) into a six-year study to learn what happens to the human body (and, of course, mice) during exercise. The “Molecular Transducers of Physical Activity Consortium” ( MoTrPAC) project has Francis Collins’s fingerprints all over it: the man clearly loves big initiatives (e.g. the Brain Initiative, the Heal Initiative on chronic pain).

The NIH is confident they can now get at the very molecular root of exercise, including identifying every single molecule in the body that’s tweaked or turned on by exercise.

MoTrPAC will intensively examine what happens to 2,700 active or sedentary healthy adults during exercise in ten clinical centers across the U.S. (One of those clinical centers, the Center for Exercise Medicine, is at the same university (University of Alabama at Birmingham) that Jarred Younger’s Neuroinflammation, Pain and Fatigue lab is located.)

The study is so large that it will take eight sites – including Bruce Snyder’s Lab at Stanford – simply to analyze all the samples gathered. The goal is to create “a comprehensive map of the molecular changes” that occur during movement; i.e. to fully understand just what exercise does to the body.

The amount of data to be gathered is so immense that Maren Laughlin, a program director for integrative metabolism at the NIH, sputtered a bit when talking about the amount of data it will gather: “It’ll be a tremendously enormous data set,” she said.

This is a big, slow-moving, apparently agonizingly considered study. The program was announced in 2015, and the MoTrPAC program awards were first presented in December of 2016. Since the awards were announced, it’s taken almost three years to work out the study methods, establish clinical and data standards, create a research data portal, design recruitment strategies, etc. Only this fall did the study actually begin to recruit subjects.

Blood, plasma, urine, tissue and who knows what other samples will be taken before and after a single exercise period and before and after an exercise training regimen.

No Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS) Focus (Yet)

One might think that a huge study focused on how exercise affects the body would feature at least some people for whom exercise does not work, but no – the study will look at some people on the other end of the spectrum (marathoners), but people with ME/CFS or overtraining syndrome are not included.

My guess is that they will actually get some people with mild ME/CFS in there, though; people who can work but are sedentary because they simply hate to exercise. If some of them participate in the study, the NIH may learn something about exercise intolerance.

Collins acknowledged that exercise is not a one-size-fits-all type of activity – that different people do better with different exercise regimens. What works for him, he said, might be very different from what works for someone else. No kidding. Doctors, he said, are unclear about what types of exercise to recommend. Really!

If one goal of the initiative is to create personalized exercise recommendations, one would hope it would be interested in the personalized, evidence-based exercise regimens that groups like Workwell have already developed specifically for people with ME/CFS. This is a field which called out for the development of unusual exercise regimens and introduced a new term – post-exertional malaise – to the medical lexicon.

It’s true that the initiative doesn’t contain any disease groups, and that may be why ME/CFS is not included. It’s hard to understand, though, how a massive initiative focused on exercise (e.g. activity) is not interested in the exertion intolerance disorder (remember Systemic Exertion Intolerance Disease (SEID))? Collins has again and again called for more research on ME/CFS, yet missed a golden opportunity to include ME/CFS in an enormous initiative directed at understanding the heart of the problem in ME/CFS – exertion. It’s baffling and disappointing.

There is a possible “in” for ME/CFS though. The NIH is encouraging outside investigators to apply for “ancillary studies”.

“MoTrPAC encourages investigators to develop ancillary studies (AS) in conjunction with the MoTrPAC study and to involve other investigators, within and outside of MoTrPAC, in this process.”

It seems like a perfect opportunity both for us and them. Understanding exercise intolerance is, after all, the flip side of understanding why exercise helps. Plus, because the heart-based exercise regimens developed for people with ME/CFS do help, they fit the personalized exercise prescription thrust. Having people with ME/CFS participate would benefit the initiative and us.

The News section on the MoTrPAC website, however, lists only two dates to apply for an ancillary study – the last of which ended in April, 2018 – which brings up the question of whether the NIH ever informed ME/CFS researchers of this opportunity.

Digging Deep

The $170 million indicates not only that the NIH is very serious about learning about exercise, but that it knows it has a heck of a lot to learn about it. That’s very good news for a disease defined by exercise intolerance. They will be digging deep indeed.

- The Pacific Northwest Group will analyze the proteins circulating in the blood and tissues before and after exercise. They’ll use those proteins to investigate the “cross-talk” that occurs between and within tissues and assess things like how exercise changes proteins (protein and lysine phosphorylation).

- In what may be a very illuminating study for ME/CFS, the University of Michigan Group will use novel techniques and technologies to do metabolomics profiling in an attempt to understand how exercise relates to metabolic health.

- In an attempt to understand the “intra-organ circuits” and “within-organ responses” that occur during exercise, Duke University will integrate metabolomic, proteomic and genetic findings.

- The Mayo Clinic at Rochester will identify how the metabolites and proteins in the plasma, muscles and fat are altered during exercise.

- The Icahn Center at Mt. Sinai will identify molecular responses to exercise, develop new hypotheses regarding how exercise affects the body, and develop predictive models of how individuals respond to exercise. That last one will be fascinating given the predictive models Nancy Klimas’s and Gordon Broderick’s groups have developed regarding how people with ME/CFS respond to exercise. (Gordon Broderick is now at Rochester.)

- Emory University will employ “metabolite forensics” to identify metabolites new to science and identify key players within “the proteome, ubiquitinome, acetylome, kinome and nuclear proteome”.

- Mike Snyder’s lab at Stanford University will do the genomic heavy lifting through its genome sequencing (3,000 genomes, 40,000 epigenomes, 40,000 transcriptomes). It will also assess the effects of exercise on exosomes and chromatin. Plus, Snyder’s lab will incorporate the genetic data, transcriptomes and exercise activity it already has for almost 1,000 people. The Stanford group has already identified many genes that are affected by exercise.

An Aside

The NIH believes it will be able to uncover all the molecules in the body that are tweaked by exercise.

There is one bit of good news from the Time article on the nature of exercise itself. More and more research shows that exercise does not need to be lengthy or exhausting to have a beneficial effect. Exercises which employ resistance such as yoga, tai chi and pilates are as effective a means of strength training as weight lifting.

Plus, researchers are also finding that short but intense exercise periods are as effective as longer exercise periods. One study found that a 10 minute micro-workout which consisted of three exhausting 20 second bouts of intense exercise followed by recovery periods produced the same heart and blood sugar effects as a 50 minute workout. One researcher was working on one-minute exercise programs. Very short exercise protocols are recommended in ME/CFS as they use the anaerobic energy production system.

Conclusion

“There is so much we need to learn about normal responses to exercise that we could apply to ME/CFS. Anything they find will help ME/CFS because it will increase our understandng about exercise responses. It’s a fantastic opportunity.” Staci Stevens, Exercise Physiologist, The Workwell Foundation

The study will open new doors for exploration in ME/CFS (if we can find researchers to look behind them). (Image by Arek Socha from Pixabay)

While this is not (yet) an ME/CFS study, it will, in its present form, give us the next best thing: the biggest darn baseline possible on the core issue (exertion) in chronic fatigue syndrome. It seems inconceivable that this immense exercise study is not going to give us many new leads to check out. As the researchers learn exactly what happens on the molecular level during exercise, they’ll be identifying critical factors and processes that are needed for exercise to work.

Those will give us a new roadmap that will help us track down what’s gone wrong in ME/CFS. Is a vital protein not being produced? Is a strange immune factor shooting up during exercise? Are some strange genes going bananas in ME/CFS? Are systems not talking correctly to each other?

Despite the fact that the NIH missed a huge opportunity by not including exercise intolerant people in its mega exercise study, this may very well turn out to be the most important study ever done for the ME/CFS field.

That will only be true, of course, if researchers are interested in translating the results from these studies into actual ME/CFS studies. With Jennie Spotila showing that individual researcher grant funding is actually declining, our greatest task may simply be finding researchers willing to give ME/CFS a shot.

Moving Forward

In the meantime, some major question remains unanswered – why are we – a disease defined by exertion intolerance – not in the study, and how can we ensure that we benefit from it? Some ideas are listed below:

- We should find out why we are not in the study.

- If a special effort was not made to make the ME/CFS research community aware of the ancillary grant opportunity, we should know why that didn’t happen.

- We should ask what is the NIH going to do to ensure that the benefits from the study quickly accrue to the ME/CFS field. Given our pitifully small researcher base, it could take years and years for us to derive benefits from the study. Therefore, as the results of the study emerge, the NIH should promise to do a funded grant application (RFA) on how exercise affects people with ME/CFS. (If they can spend $170 million on exercise, one would hope they would be willing to spend $10 or $20 million on the exercise intolerance afflicting 1 million or more people in the U.S.)

- We should be able to use this missed opportunity to demonstrate to the NIH that they’re not doing their best to move the ME/CFS field forward.

Please Keep the Reporting Going – and Support Health Rising

It is for me shocking. you see, if they want, there is money! Only not for ME/cfs!

I do not know if it is complete, but heard from the double excercise study for ME/cfs : 60 patients, 30 MEers, 30 controls at 3 different sites. Uncertain when the research will come out. Another smaller study with 20 patients will be next year.

what a contrast! and in my opinion, collins is certenly not on our side.

and you can give it a twist, that it will be good to have these data for comparison with the little data on Me/cfs. but it is a shocking twist. again and again and again.

In the severelly ill group there are people dying now, there are people who are on the end of there rope, there have allready people been dying or they say such a terrible desease…7 times more suicide! how would it come?

but no, no money for it again. how easilly they would have got taken a part for me/cfs in this large study with so many millions!? And these are all healthy people they test!

when will we get 170 million for research????

I have more and more no strenght anymore to breath properly, my heart pumps to slow, am lead and completely weak laying on bed, have trouble eating, etc and with me so many others.

they simply do not care!

I really am in shock!

It is shocking. I didn’t hear about this study until a day or two and it’s been in the works for over 4 years. I don’t know but my guess is the NIH never even attempted to contact ME/CFS researchers about it. It’s possible that the NIH with its emphasis on understanding the benefits of exercise didn’t want any diseases in there. It’s also possible we didn’t even come up as a possibility. Who knows? I would dearly love to find out.

Just being in the study could have told us what’s happening in ME/CFS. It would have increased funding dramatically and introduced us to a whole new cadre of researchers who probably would have been fascinated by the disease. What an immense opportunity missed!

Once you get past that upset (I had several hostile imaginary conversations with Collins dancing in my head when I learned about this) though, I don’t see how this study will not be of immense value to us. It could very well give us the keys to unlock what’s going on in ME/CFS.

So despite the upset – I think its a huge, huge win for us.

I had a frightening thought about this study though, and hope that you or someone else can talk me out of it Cort. If undiagnosed PWME are included in this study as deconditioned people, won’t the exercise test results for the PWME who are mistakenly included then be considered part of the normal bell curve for deconditioned people?

In other words, don’t PWME and other forms of exercise intolerance have to be studied as part of this effort apart from deconditioned folks in order to distinguish what true decondtioning is from exercise intolerance? Seems to me like you wouldn’t get an accurate picture of what deconditioned is without separating out the people who have exercise intolerance and vice versa.

How would we get an answer to these concerns from Francis Collins?

Avid Reader makes a great–and deeply depressing–point.

Good point. I hadn’t thought of that. I would hope, though, that these two groups would get naturally differentiated through the study – they would have different exercise test results and I would strongly presume different metabolomic, proteomic, etc. results. If ME/CFS patients got into the study I would hope the NIH would end up with this weird class of sedentary individuals which looked very different from the other group of sedentary individuals. In the best of worlds they would figure out – and we would help them 🙂 – that those are probably people with ME/CFS! People who’s aerobic energy production systems are broken….May it be so.

In attitudes to ME/CFS we are fighting very deeply embedded cultural factors.

One thing that the internet and social media has exposed is the depth and extent of misogyny throughout our culture. From ‘metoo’ to ‘Doing Harm’ to increasingly misogynistic political trends, especially in the US., the dismissal of women’s testimony and the challenges to our health and even our physical safety are more and more apparent.

I even found myself colluding in a simple linguistic gender put-down. Men ‘report’ their medical symptoms. Women ‘complain of’ their medical symptoms. Men get diagnosed, women get reassurance that ‘nothing is really wrong;. Men get painkillers, women get tranquillisers.

ME/CFS is the quintessential feminising disease…we become physically weak, complain of many, variable symptoms, don’t get better, go on complaining, go to many different doctors…

We are therefore classical ‘medically unexplained symptoms’ people…clearly therefore we must have a psychiatric problem. The fact that we generally have a life narrative that is the opposite of one that could possibly explain a mental health issue…we are active, successful, energetic, positive people who don’t give in to illness – an especially typical narrative in the severely and very severely ill – doesn’t get in their way at all. They simply blithely assert that ME/CFS proves that you can get a mental health problem without an explanatory narrative.

I suppose we ought to rejoice in our feminine ability to acquire a seriously disabling but non-existent disease which has no medical explanation…and also no psychiatric explanation.

Or is this just further evidence of male objectivity and logic?

The history of ME/CFS within the CDC and the NIH seems to confirm that gender prejudice defines what happens.

Money is awarded, let’s just steal it.

Where shall we include it? In the Office of Women’s Diseases…which has no funding allocated to it.

Patients continuing to protest? Let’s make speeches assuring them that we’re really going to do something about it, while reducing. actual funding.

We’ll show them we mean business by having an ‘in-house’ research programme. Which will be run by a person who thinks it’s a non-disease, and will process one patient at a time through two-week recording sessions, so that no results can be expected for years.

Oh, and invite one of the most virulent, misogynist ‘it’s not a real disease’ doctors down from Canada to talk to us.

And let’s run an enormous research project on exercise without any consideration for the possibility that exercise could do harm.

(A recent Twitter feed quoted a doctor terrified her colleagues would discover her recent ME/CFS diagnosis: ‘Doctors have even more contempt for patients with ME than for patients with depression.’)

With this deeply culturally embedded current of contempt pretty much in control…with some honourable exceptions…(Invest in ME, the Open Medicine Foundation among others) I find few grounds for optimism.

http://www.positivehealth.com/article/cfs-me/what-can-we-expect-from-the-current-review-of-nice-guideline-cg53

Your comment is so true… so depressingly true. Being a woman is no fun. But being a woman with ME is just hell. I hope one day there will be a ME-Too movement so that people can have a glimpse of how we are being treated.

Hi Isa,

I received an email from the OMF, I’m on their mailing list, about this very topic!

Ron Tomkins and Amel Karaa MD are looking into how ME/CFS patients are treated.

‘Harvard Affiliated Hospitals examine ME/CFS Patient Care.’

‘This group of doctors is committed to improving patient care and outcome and hope to create a model for others to replicate’.

I personally believe the extraordinarily poor way that ME/CFS patients are frequently treated is a humanitarian crisis.

I also think that the level of bewildering isolation that this can create for the patient, is extremely unhealthy.

Tracey

Hi Tracey,

Thanks for the info. I found the link.

Isa

I agree with Nancy Blake and Isa.

“men report their symptoms, women complain of their medical symptoms”. That one little sentence says sooooo much about how women are treated in the medical establishment (especially bad with M.E.) I know it is no cake walk for men either, but there is this deeply ingrained “hysteria” concept foisted onto women, a gaslighting of their reality. It is better for me now, but 10 years ago when I was first ill and still seeing many drs (most male) it was very bad indeeed. Thank you nancy blake for your eloquent and accurate description.

As I read this it angered me even more what a disappointment. This me/CFS and all these incurable BioWare illnesses has got to be a part of the Agenda 2030 plan for a reduced population. I am in same shape as KONIJIN, dont know if I will live though the day. I welcome a long rest.

Thanks for the very good report, Cort, and thanks for maintaining such a positive perspective on the study, even though ME/CFS is remarkably not included! “When will they ever learn”!

Agree! Thank you Cort also!?

Thanks for posting this. I know we needed help yesterday and empathize with the other commenters.

At the same time, I see this type of foundational research as highly important to solutions for patients with ME/CFS. Results from these studies combined with analytical reasoning could provide new insights and research avenues. It is a *new* open platform that could be mined by ME/CFS researchers and useful for attracting young researchers to submit grant applications.

you wrote: “It is a *new* open platform that could be mined by ME/CFS researchers and useful for attracting young researchers to submit grant applications.”. yes, I understand that. but the big problem is that there is no such money for me/cfs researchers. So, unless there finally would make free tons of money every years for me/cfs researchers, it will us help in no way. yes, with litlle studys sponsored trough patients of 15 ill ones or so. not verry statistic. I may be wrong but thought that the larger studys like naviaux (was it + 300 patients) we can count on one hand. I knew someone in breastcancer research and he saw everyday hudreds of 1000+ patients papers. where do we stand with me/cfs?

This is the problem facing us in my opinion. I wouldn’t say, though, that there’s no money for ME/CFS research. There’s actually potentially tons of money for ME/CFS – anyone can apply for a grant and grant approval rates look just fine in ME/CFS but very few researchers are willing to do that. Thus far this year only 9 applications for ME/CFS grants have gone through.

There’s isn’t any set aside money to entice researchers to enter this field though. Absent that our they’re not doing it. That brings up the possibility that this big study could hand us the keys to ME/CFS but we might not have the resources to put them in the lock and open the door.

Yes, indeed. Thankfully the database – the “user-friendly database” 🙂 (let’s hope!) – will be open to researchers. Even if we’re not in it now this researcher HAS to, just has to, open up potentially critically important areas of research for us.

If we know how a system works when it works right – we can check to see how our systems went wrong. After actually being in the study, I think this is the best study we could have hoped for. I fail to see how it will not provide major and hopefully fundamentally important opportunities for our field.

I hope David Systrom knows about this big study.

I agree, it’s outrageous the lack of funding toward ME. For those of us that are severely ill, their inaction is killing us.

Cort, or anyone knowledgeable in the politics of this: is there any way we can protest and push to some kind of alteration of this intention to make the study more directly useful to understanding ME/CFS? Are the advocacy groups we support looking into this? How did it get by them in the first place?

My guess is that no one was ever contacted. I imagine the IACFS/ME would have sent something out to their members. ME Action and Solve ME would have been all over it. I certainly would have sent something out.

Collins was instrumental in getting Nath’s intramural study going and an exercise stressor plays a fundamental role in Nath’s study. Collins knows what’s going on with exercise in ME/CFS.

This is a 2700 person, $170 million six-year study. Even if the study is aimed at elucidating the positive benefits of exercise there’s gotta be ways in a study this size to get other groups in. I can’t believe that the NIH can’t find a way to fit a hundred or two people with ME/CFS in there. For one thing they would learn a lot about exercise from us.

They’re going to be testing all sorts of exercise protocols in all sorts of people. I would think the researchers would be fascinated by the heart rate based exercise protocol developed for ME/CFS.

The problem is we weren’t in the room when the study protocols were being developed. No one thought to ask us about what to put into a comprehensive exercise study.

Thanks for the question. It spurred some ideas and I inserted them into the blog at the end of it.

Yes, all of these. These are relevant serious questions; to whom do we direct them? How do we do this? I’m so frustrated-we we’re super active and now can’t even advocate for ourselves without causing ourselves harm!

Thank you for your wonderful work.

I assert that one thing this study does is provide us a great opportunity to ask for RFA to build off it. If the NIH can spend $170 million on exercise and then can’t fund an RFA to apply the results to understand what’s going on THE exercise intolerant disease, I don’t know what to think. I don’t know why they wouldn’t do that actually. It’s an easy win for them! Hopefully it will provide a more or less clear pathway to understand this disease – exactly what the NIH has wanted for ages.

By then the Nath study with its double exercise stressor should be done (hopefully) and it should provide some real insights.

Agreed re how the work already down by ME/CFS researchers should help them a lot. Its a waste of time and money not to consider it. But…Besides the problem of compartmentalization at the fed level, though, there’s also the problem of turf and competition. But I think getting more info before it is to late to get in would be a big step forward. The question is how the ME/CFS community can proactively do that.

Take it to your Reps. and Legs. in your State that represents you..Email or call and Nicely ask them are they Aware and Ask could they possiblity Support ME/CFS and could they look into this problem and help in anyway…

I know this is upsetting, disheartening and we feel left out once again but yes, the Why’s? Needs to be addressed Publicly…We are entitled to that the very least..that/the answer(s) truthfully..the reasons..possible only hearing crickets chirping? but at least Awareness happened..?You did your part.. Community

My thoughts and opinion..?

I don’t know the system in other Countries..sorry?

Cort is right about the grants and the where the need of Old and New Researchers to get involved and interested in Us..(Grants) File for them..We need alot of Researchers in different areas and fields including Engineers..

Awareness,

Education,

Collaboration,

Togetherness..

Open Communication on everyones part to help..

Oh, Nice, short and sweet to the point when asking

Cort didn’t you clarify in one of your comments as who’s who and thier role..I can’t remember that info. which would be nice in understanding for everyone if you could post again..ty!

Hi Lora,

I did contact a local politician, who I thought might help me. She then submitted a parliamentary question about establishing the current situation with ME/CFS within the Irish Health Service.

The Health Minister replied, mentioning ‘relevant specialists’ and accessing them ‘through out patient clinics at secondary care level’, referred by GP’s ‘if appropriate.’

My reply back is – who are the ‘specialists’ and where are they?

Also as my Primary Care group of doctors don’t appear to recognise ME/CFS (apart from being a psychological/psychiatric issue), they are not looking to refer me anywhere…

So, again we’ll see what happens with my small bit of political engagement!

dear cort, sorry, me again. I do not understand the lack of researchers. As I hear (webinars) from ron davis-OMF there are researchers who would like to do research on me/cfs but who they can not hire when they even can not say that they will have a job anymore the next yer because of money. sole me/cfs, simmaron, etc have also all researchers who are payed for litlle studys by patientcommunity. I really do not understand that there would e no researchers enough. there are at omf even who work for free, umnpayed because off this catastrofic desease and funding.

I don’t either. Ron Davis and his group have actually been very active in the grant arena. If everyone in this field was applying for grants like they are we wouldn’t be in this trouble. I imagine that Ron Tompkins will be applying for grants now that he’s in the field full-time. Nobody is probably better at getting grants through than him; his Glue grants were longslasting and enormous. He’s a huge asset to this field.

Otherwise it’s very confusing to be honest. There seems to be more happening and more positive and interesting studies than ever before but researchers are actually applying for grants in record low numbers. I don’t understand it at all.

As I always say there is Power in Numbers..

Sqeaky Wheel gets greased and Data and Facts speak Volumes..

Just because someone says something doesn’t make it right nor true that is where

(Data,Facts,Stats,Theories, Hypo.) Stand Alone

Without Monies set aside to implement things (Resources) and ect.,your at a stand still..

So that is where donations is/will/can help in the meantime from the private sec. and/or public sec. to help success with much needed resources and to fill in the gap(s) elsewhere..

It takes time to get published and so on…

Alot hoops to jump thru,

turtle pacing plus red tape but nothing is impossible..stay hopeful All!

Things are moving in the right direction..?

Thank you, Cort, for bringing this immensely wealthy study to our attention but it really is a double-edged stinger. Is it possible that inclusion was over-looked and that Collins or someone else could be helpful in adding ME/CFS to the study? God, that’s a lot of money and people and not us!

One more thing, would you lead me to the information about the heart-healthy exercise for ME/CFS? Thanks in advance. Always thanking you. For good reason.

Hi Linda,

These 2 resources might be helpful to you:

. specific guidance for patients: http://workwellfoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/When-Working-Out-Doesnt-Work-Out.pdf

. specific guidance for a patient’s PT (physical therapist): https://academic.oup.com/ptj/article/90/4/602/2888236

. an interesting case report on a patient: http://workwellfoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/Functional-Outcomes-of-Anaerobic-Rehabilitation-in-a-Patient-With-Chronic-Fatigue-Syndrome.-Case-Report-With-1-Year-Follow-Up.pdf

I got these from Workwell’s Resources page, where they also have lots of excellent videos, with more coming soon:

https://workwellfoundation.org/resources/

Good luck!

I am over 3 decades ill, was mistreated with get in the beginning, half years antibiotics (horror, almost died), long term bedridden (caan not count even the years), would an “excercice” program still help me if I am even struggling for food? and after all these decades and alone with almost no help and bad homephysician?

thanks!

I’ll check on all these links, and thank you, Cort!

Here’s another report on the woman who improved so much on Workwell’s exercise program.

https://www.healthrising.org/blog/2013/08/13/heart-rate-monitor-program-improves-heart-functioning-in-chronic-fatigue-syndrome-mecfs/

I love the term “molacular transducers of physical activity”. It sure sounds like myokines and maybe that’s where they are going to start with. We only understand tiny fraction of immune system language and this project will probably spend lots of effort in understanding it in connection with exercise. Once we undertand the language enough, maybe we’ll be able figure out how some words get misinterpreted and result in exercise intolerance.

In the video, Collins talk about “one size fits all” approach of today’s exercise medicine and personalization once we undertand the exercise physiology better. I hope one of the personalizations will be for CFS patients.

“It’ll be a tremendously enormous data set” Is that the same as “bigly great”?

At a whopping $40,000 per participant, one would certainly hope something useful comes of it. Otherwise, taxpayers are screwed again–along with those of us with ME/CFS and fibromyalgia. How in heck are they coming up with ways to blow $8,000 PER PARTICIPANT PER YEAR JUST TO MEASURE THE EFFECTS OF EXERCISE?!?! That is half my gross income, thanks to this disease having destroyed my life as I approached what should have been my prime earning years. Talk about salt in our wounds…

More like sliding down a razor blade and landing in a pool of alcohol..Metaphor. and painting the pic with words is one of my coping meck. ???

I am in the same boat as you are and that how I feel about..to keep from crying or even worst thoughts..?

A sort of black humour – much better than reality!

Someone wrote in a comment I can’t find now, that they would list more of their symptoms but their brain was listening, so she’d better not!

I prefer to look forward and keep just ahead, if I can, of the darker realities of my situation… Much healthier ?

I think bigly great is a quite close approximation 🙂

Jeez Louise I actually did a blog on this about two years ago. https://www.healthrising.org/forums/threads/the-great-nih-exercise-initiative-a-boon-for-chronic-fatigue-syndrome-me-cfs-and-fibromyalgia.5174/

I had completely forgotten about it.

Geeze, Cort.

Is there not a way the Workwell Foundation, Dr Nancy Klimas, Ron Davis’s Stanford group (he’s a genome guru), Maureen Hansen’s exercise scientsts, etc could somehow do an “ancillary study” for ME/CFS along with this this huge NIH exercise project? Could they use some of their existing data, stored blood samples, etc and measure PEM along side all of the work this study will cover? There has to be a way for ME to benefit from this.

It is very fishy that you of all people just found about it. Most of are not scientists, and even if we were, we wouldn’t have the energy to tackle grant writing. It sure feels like they went out of their way to exclude us. How very frustrating!!

Yes, it’s rather painful given all the exercise data we’ve already produced and will be producing not to be able to participate in this study.

Looking at the announcement the study creators decided to have the study examine only “highly fit, athletic participants as well as non-exercised sedentary controls. All study participants must be healthy and capable of participating in physical activity interventions” (https://grants.nih.gov/grants/guide/rfa-files/RFA-RM-15-015.html )

We obviously weren’t in there calling for at least a small sized ME/CFS contingent when they created this study. We weren’t in the room.

Still I would have hoped that they would have been open to an ancillary study with ME/CFS in it. However, no more funding opportunities are available for this study. They apparently closed last year and the study appears to be set. No effort was made to get this information out to ME/CFS researchers probably in part because of the studies criteria – we’re not healthy people able to engage in exercise.

This study should still open huge opportunities for us. I think making request for an RFA to help us realize those opportunities is a great idea.

Cort, great blog. Just checked the MoTrPAC website and it appears they

still have information posted re: ancillary studies as well as contacts/e-mail addresses for each study site. Perhaps you could pass that info’ along to our exercise experts for their future planning. I think you mean Mike Snyder at Stanford?

https://www.motrpac.org/ancillarystudyguidelines.cfm

The only thing that makes me madder then sick people being ripped off over and over. Is watching everyone who can hardly stand or talk yelling at brick walls to listen. They are brick walls. They will never listen or care. Stop wasting your money they are not finding anything more than salt in your lifetime or mine. Stop wasting your time and energy writing to a shredding machine that’s what you are doing. If you think they want to help you you have everything backwards they only want to help themselves. Throw out your TV stop wasting time all social movements are co intel wake up. Me too Is 100% men. Look.

Govt run. They are going to do us like cancer go in circles big bucks no cure EVER. Giving up hope is the BEST thing you can do and the HEALTHIEST. Not one of these so called scientists sounds like they ever talked to a real M E patient. They haven’t even managed to take out the word fatigue from when they describe it in their lectures. Puleeese. Just take care of yourself and stay out of the mess of insane indoctrinated doctors. They will do a number on you.

Hi Konijn,

I think you are right to put “exercise” in quotes, the way you did — many programs for people with ME don’t look much like pre-illness exercise.

I don’t know if you would have access to a PT – but if you did, they should evaluate your current condition before prescribing any exercise. They could use the article at the link I provided.

Whatever you did, it would be guided by you — that is, it has to be safe and not cause PEM.

Keep in mind, this “exercise” could well *start* at, for an example, 3 repetitions of a leg stretch, while lying down — 20 seconds max for the entire session— and not be repeated for a minimum of 2 days.

The goal for many ME patients is to increase ability to do activities of daily living (like washing dishes, etc).

Workwell explains it better on their website – maybe check out a video there where they explain “safe for ME” exercise.

thanks! I watched the links you put there. and have send a mail to them with questions. going to further explore there website.

I think there has to be a better communication/information dissemination effort from the NIH — AND, there has to be better sleuthing by our advocacy groups. Hopefully CFSolve will set up a new system to monitor grant solicitations. I think we know we can assume by now that the feds aren’t going to go to any effort to notify us. We have to have a monitoring system to see all the rfps from the feds.

I don’t know if this information is still valid, but here goes;

Last name Collins

First name Francis

Middle name S

Agency NIH

Organization DHHS/NIH/OD

Job title Director NIH

Building 1

Room 126

Duty station Bethesda MD 20892

Phone 301.496.2433

Internet e-mail Francis.Collins@nih.hhs.gov

I would appreciate it if anybody could update this if it is incorrect.

I realize that Director Collins probably has a cadre of underlings who screen mail and other communications, but maybe, just maybe, if anybody wants to write, something may get through.

Perhaps someone else could find the contact information for the person managing the MoTrPAC program.

If one cannot get in the front door, perhaps the back door will work…

Nancy, names and e-mail address for MoTrPAC Coordinators are listed here:

https://www.motrpac.org/aboutUs.cfm

Gemini, thank you so much for that link!!!

Now, to find the time and ENERGY to write to these people!

Maybe someone will notice many mice squeaking at the back door!

I agree Nancy,

I have to build up a bit of brain energy to formulate what I’m going to write and I have to be careful that I don’t deplete my store first thing in the morning, so I’m mentally wrecked for the day!

However if we chip away at our own pace, in whatever way we can, whilst focussing on looking after ourselves I think it’s all worthwhile.

I was saying to my 16 year old son, how I like to check what people are posting on HR and he replied ‘Mum, you’re addicted to social media!’

In my quest for information on the current situation of ME/CFS in Ireland I contacted the Irish ME Trust, (I am a member).

They informed me that an ‘ME Working Group has been established by Disability Services, Health Service Executive (HSE) – Marie Kehoe-O’Sullivan (Chair) for the purpose of developing a Guidance Document on pathways to support people with ME’. The Irish ME Trust are involved.

The group are looking for people to be part of the group and are developing a ‘survey tool’ and ‘will offer the survey online, in paper, by telephone and where necessary if you are home-bound in person’.

I said I’d love to take part but I have no formal diagnosis – catch 22.

Declan Carroll from the Irish ME Trust (IMET), replied that as 90% of people with ME have no diagnosis, it would be very important for me to participate.

So, I most definitely will do!

Interesting what turns up with a bit of amateur delving…

Tracey Anne et al — How about suggesting to the advocacy groups that *they* do the contacting? I think sometimes they need some direction from those for whom they want to advocate. Also, I reiterate my suggestion that they set up a continuing system to monitor *all* proposals for research (or RFPs, requests for proposals) that the various agencies who might finance ME/CFS research issue — and not rely on being contacted directly by the agencies. It would appear they didn’t see how ME/CFS could piggy-back on this $170 MM study and give everyone a bigger bang for the buck. I wonder how many other studies funded for ostensibly “other” health questions ME/CFS could and should piggy back on. The feds are not known for doing things efficiently. But the questions I’m asking just beg to be asked. There are computers now — if some good IT people could set up the system(s) it shouldn’t be impossible to monitor things.

I’m curious, Cort — how did you find out about this $170 MM study? Maybe that could give a clue as to how to find out about other things while there is still time for ME/CFS to try to get included.

Hi Cameron,

Yes, I did think it was a bit strange that I hadn’t heard anything about this working group and possibly could have missed inclusion in it.

Maybe all members of IMET will be invited to take part and I just happened to prompt this information early?

I don’t know.

People’s lives are ticking away and some people are surviving on the edge of a precipice – a sense of a bit more urgency would be welcome…

AvidReader made a very good point (November 14). I wonder whether some ME/CFS researcher(s) can be included in the selection of subjects in this study. Or somehow else in this study. My thought isn’t very well formed, but it seems to me that is a really important point and possibly still a door in for one of our very smart researchers — if they have the time. I also wonder, somewhat tongue in cheek but also somewhat seriously, if a group of “outliers” will emerge and they will wonder what to do with them; viz., if undiagnosed people with ME/CFS will emerge as a subgroup.

PS Re the rfp monitoring process I’m wanting, universities and corporations (and biotech companies and pharmaceutical research companies and…) must already have these set up. It’s more important than ever to be proactive and not wait to be notified, as this study Cort found out about shows us. And the monitoring criteria can’t be too narrow: specifically, not just limited to having “ME/CFS” in the title. It seems to me that attaching an ME/CFS component to other seemingly non-related studies might be helpful. At least, minds should be kept open as to the possibility.

Hi Cort and All..

I am not sure if you or others are aware of MEActionAlert and there petiton to NIH but here is the link for the petion in response to NIH head Dr. Letter

.People are making videos as well to him asking for help and in response of his letter back to the letter MEActionAlert sent him

#Notenough4ME..

Petiton

https://act.meaction.net/page/13656/petition/1?chain&ea.tracking.id=web

Just thought everyone like to know in case they wanted to sign the petition..