From Dominic

I believe observations made in Intensive Care Units can further understanding of ME/CFS.

Indeed, following a severe injury or infection some ICU patients fail to begin recovery for unknown reasons. This condition, termed “chronic” or “prolonged critical illness,” is characterized by neuroendocrine dysfunctions perpetuated by cytokines and oxidative/nitrosative stress. Regardless of the initial injury or infection, patients experience profound muscular weakness, cognitive impairment, pain and other severe ME/CFS-like symptoms.

Given these similarities, I believe that active collaboration between critical illness and ME/CFS researchers could lead to solutions for both conditions.

Please see my brief blog post below (first published on Health Rising). Any feedback is much appreciated.

Thank you for your consideration,

Dominic Stanculescu

Note: This blog post is based on a series of longer blog posts (see list at the bottom of this post) — references are cited in these posts.

The stress of a severe injury or infection induces endocrine changes that may persist independently of the initial trigger and cause patients to become chronically ill. (From Wikimedia – https://www.wikiwand.com/en/Intensive_care_unit#/media/File:Respiratory_therapist.jpg )

There are generally three possible outcomes for patients admitted to Intensive Care Units (ICUs) following a severe injury or infection: some die within days, others start recovering, and yet others appear to be “neither dying, nor recovering.”

These latter patients are labeled as suffering from “chronic” or “prolonged” critical illness.It’s important to note that any severe injury or infection can lead to this condition, including head injury, severe burns, liver disease, pancreatitis, HIV infection, sepsis, cardiac surgery, etc.

Irrespective of the initial injury or infection that brought them into the ICU initially, these chronic patients generally experience fatigue, profound muscular weakness, cognitive impairment, loss of lean body mass, pain, increased vulnerability to infection, skin breakdown, etc.

Endocrine dysfunctions

Critical illness researchers have found that most of the debilitating symptoms of prolonged critical illness are due to endocrine dysfunctions – i.e. changes in the production and metabolism of hormones.

Here it is important to note that the endocrine patterns observed during the initial “acute” phase of critical illness (in the first few hours or days) differ markedly from those observed during “prolonged” critical illness (after a few days). Researchers only fully realized this distinction in the late 1990s.

Indeed, endocrine changes during the “acute” phase allow the body to prioritize certain functions (such as fighting infections and healing) over others (such as digestion or reproduction). They are thus considered adaptive and necessary responses to the stress of a severe injury or infection.

Endocrine patterns that appear during the “prolonged” phase, however, appear to inhibit recovery and are now increasingly considered maladaptive. It is the endocrine patterns that appear during the “prolonged” phase that are reminiscent of what is seen in ME/CFS and FM.

Pituitary Gland Suppression

The suppression of the pituitary gland’s pulsatile secretion of tropic hormones is central to prolonged critical illness. In other words, the signals emitted by the pituitary — in the form of specific pulses of hormones targeting the “downstream” endocrine glands (e.g. adrenal gland, thyroid gland, liver and gonads) — are disturbed.

Note that changes in these signals can only be fully captured by repeated blood tests performed day and night — as often as every 10 minutes. The failure to do this might explain why the endocrine dysfunctions in prolonged critical illness were only documented in the late 1990’s.

This suppression of the pituitary secretions has severe consequences:

- Without sufficient pulsatile stimulation by the tropic hormone ACTH the adrenal glands begin to atrophy, compromising patients’ ability to deal with all kinds of external stressors, and permits excessive inflammatory responses.

- Suppression of TSH release from the pituitary causes weakness and cognitive and organ dysfunction.

- Erratic rather than pulsatile production of growth hormone by the pituitary leads to an imbalance between catabolic and anabolic hormones – in other words, between hormones that break-down proteins and those that build proteins. This results in loss of muscle and bone mass, muscle weakness, and changes in glucose and fat metabolism.

- Finally, the suppression of FSH secretion can lead to muscle weakness and increased pain sensitivity.

Again, the one-time lab reading cannot capture the extent of the endocrine dysfunctions occurring during prolonged critical illness. Indeed, the concentration of tropic hormones at any one time gives little indication of the frequency and amplitude of their release by the pituitary, which is a determining factor of their function.

Pituitary pulsatility suppression ultimately translates into low or relatively low concentrations of “peripheral hormones,” including cortisol, T3, IGF-1 and testosterone. Similar patterns of altered hormone levels have been documented in ME/CFS and fibromyalgia patients.

Lower ratio of T3 to RT3

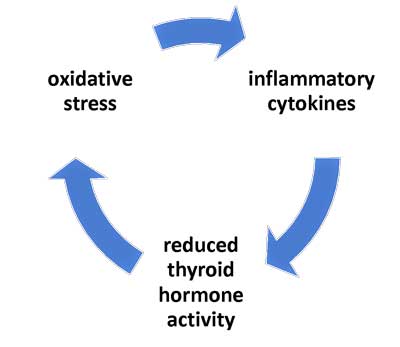

A vicious circle involving the thyroid occurs in critical illness patients – and may be occurring in ME/CFS.

In addition to pituitary suppression, another endocrine anomaly underlies prolonged critical illness: the ratio of active thyroid hormone (T3) to inactivated thyroid hormone (RT3) is lower than normal. Significantly, this same pattern has recently also been documented in ME/CFS patients. This is largely the result of changes in the activity of the various enzymes that convert thyroid hormones.

The decrease in the T3 to RT3 ratio in prolonged critical illness contributes to a general slowing-down of metabolism. Moreover, tissue specific changes in T3 and RT3 concentrations variably impact the function of the liver, kidney, brain, heart, adipose tissues, gut and other organs, and may increase the laxity of ligaments and tendons. Relatively low plasma concentrations of T3 (and prevalence of RT3) also depress the activity of immune cells, including natural killer cells.

Cytokines and oxidative stress

Research indicates that immune modulators called cytokines play a role in inducing and maintaining the aforementioned endocrine dysfunctions in a number of ways including:

- modifying the expression of the hormone receptors on the hypothalamus and pituitary

- altering the activity of enzymes that convert hormones

- changing the affinity and number of hormone-binding carriers

- varying the rate of break-down of hormones, etc.

Finally, researchers have shown that “vicious cycles” involving oxidative and nitrosative stress (O&NS), cytokines, and low thyroid hormone activity can perpetuate the endocrine dysfunctions, and thus explain why some critically ill patients fail to recover. O&NS, moreover, can cause mitochondrial damage.

Treatments

The good news is that researchers have successfully reactivated the pulsatile secretion of tropic hormones by the pituitary in chronic ICU patients. Similarly, researchers have also had some positive results in breaking the vicious cycles that can perpetuate critical illness in ICU patients. However, many of the promising treatments for prolonged critical illness are not yet standard practice, and patients continue to hang on for their lives in ICUs.

Interestingly, some of the approaches tested to remedy prolonged critical illness are used by a few ME/CFS and fibromyalgia practitioners, including supplementation with T3.

Conclusion

Are ICU patients who fail to recover telling us something about ME/CFS and vice-versa?

In sum, the stress of a severe injury or infection induces endocrine changes that are mediated by cytokines and may be perpetuated by mechanisms involving O&NS. The subsequent endocrine dysfunctions result in a slew of ME/CFS-like symptoms, including an inability to deal with stressors, susceptibility to excessive inflammatory responses, loss of muscle and bone mass, muscle weakness, changes in glucose and fat metabolism, pain, and general as well as tissue-specific metabolic down-regulation.

These endocrine dysfunctions elude clinicians and researchers who fail to measure RT3 or rely on one-off blood tests to measure pituitary secretions.

Can these observations from ICUs help us understand ME/CFS and fibromyalgia? Can the results of treatment trials for prolonged critical illness contribute to solve ME/CFS? …

Please read my blog posts to find out more about the relevance of critical illness research for ME/CFS and fibromyalgia:

- Neuroendocrine Dysfunctions in Prolonged Critical Illness: Relevance for Chronic Fatigue Syndrome ME/CFS and Fibromyalgia Pt. I and Pt 2 (Sept 2019)

- The Relevance of Research on Critical Illnesses for Chronic Fatigue Syndrome ME/CFS: A vicious cycle between cytokines, oxidative stress and thyroid hormones (July 2019)

- Pure T3 Thyroid and Stories of Recovery from Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS) and Fibromyalgia: An Overview (March 2019)

Key reference document: Here the link to arguably the most eye-opening article I have read on the topic of endocrine dysfunctions in prolonged critical illness:

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

It would be interesting if these patients have the same mutant IDO1 gene (or is it IDO2?) that Ron Davis’s team found in nearly all ME/CFS patients. The mutant gene is thought to trigger a metabolic trap (in cells) in which the tryptophan balance ends up blocking the ability to return the cell back to its normal function. (As reported in HealthRising)

The percentage of people who enter the critical illness phase seems very close the the percentage of the population that carry the IDO1 (or IDO2) gene mutation. Perhaps it’s these people who have suffered enough trauma to trigger the Metabolic Trap causing their inability to recover?

If so it would be a good idea to look for that common gene mutation in critical illness patients, as could well be the same gene. And would help narrow down research in the critical illness field to working out how to turn the gene on or off. Which in turn will help ME/CFS patients

Dear Brendan. Thank you for your comment! Yes. I was also wondering if there’s a genetic predisposition to “prolonged” critical illness. These are exactly the type of questions that I think the two research fields could inform each other on. Best wishes! Dominic

I have one of the IDO2 SNPs Pharlir discussed. I had the metabolic trap, triggered by 5-HTP. I used hyperbaric oxygen for over a year, and my labs, which indicated I was in the trap, now indicate I’m out.

I still have ME/CFS. I am better than I was, due to other treatments, like Valcyte, IVIG, Rituximab, mitochondrial nutrients, antioxidants, and various hormones, but it is more than the IDO2 trap.

I have always wondered about HBOT for fibromyalgia and CFS. May I ask what you were diagnosed with and how often did you have HBOT and at what atmospheric pressure and how many minutes over the year you did this? I am asking cause I did allot of research into this and always thought this was a main key for a cure. But you say you are better but still have it. They did a study in Israel that was pretty sucessful, 40 treatments over 2 months for 90 minutes at 2 ATA (atmospheric pressure). But they are now wanting to start a 60 treatment study but it hasn’t begun yet.

Hi Lerner, who is treating you and testing you for metabolic trap? Please share the name of Dr and/or the treatment protocol. Thank you.

Kate,

The test I did was a Genova Diagnostics NutrEval. After I was given 5-HTP, my tryptophan and 5-HIAA went very high – the 5-GHIAA was do high my doctor checked me for a carcinoid tumor, ehichbi didn’t have. They stayed high for 3 years 9 months apart, then lowered over a year and are now normal.

Lillian and Kate,

I have been doing mynown protocol after one of my doctors, an ND suggested I do it as an infection fighting strategy and anticancer (I’m a cancer survivor, but was diagnosed with ME/CFS more recently by a top ME/CFS specialist.)

I was lucky to have a fruend who owns a 1.4atm soft sided chamber, which I’ve used 1-3 times a week for 70 minutes each time. A lot of the time it makes me sleep – I sleep really deeply and feel refreshed on waking. Rarely, I get a “sick” feeling – I instinctively feel I’ve had too much and back off when it happens.

I did all this before Phair announced that oxygen could get people out of the trap, but it does seemed to have worked.

During this period, I’ve also pursued other treatments tgat have helped in other ways, which is why I believed that the IDO2 trap is only a facet of the problem. But it has definitely helped.

HBOTS can be rented monthly or purchased used. They generally need a doctor’s prescription. I go to a clinic when my friend is out of town – and pay $40-50 for a 60 min. session.

Hope this helps.

This is so intriguing! Can someone get Ron Davis to weigh in on it?

My thoughts exactly, Birdie! 🙂

I think you really need to look into oxalates, which can bind T3 hormone and create HUGE oxidative stress. We consume them in food we eat, particularly vegetables, grains, nuts and fruits.

Many of us have had antibiotic treatment which wipes out oxalate degrading bacteria, like oxalobacter, prevotella, lactobacilli, and bifidobacteria. Many of us also produce them biochemically, from vitamin C, glycine, methylglyoxal, etc.

They have been linked to fibromyalgia pain, vulvodynia pain, kidney stones, joint pain, thyroid nodules, and collect in all kinds of tissues in the human body. They are also linked to autism. They have been ignored by all but GI docs who treat kidney stones, but as these affect 10% of adults, I suspect they are far more common in fibromyalgia and ME/CFS than anyone realizes. I already know 8 payornts who suffer tremendously from them and low oxalate websites are littered with fibro and ME/CFS patients.

Although I have very little pain, I am pursuing the oxalate angle right now because I tested 16 standard deviations above the mean, the most abnormal test result I’ve ever received in my life.

Hi Tim, can you please identify the specific test? Thankbyou

Such a good report. Thanks for posting this Cort. And thanks Dominic for some really interesting material. It would be good to use the frequent testing of pulsation secretions outlined on ME/CFS people and compare that with what the pattern is in sub group of critical illness people. Has this been done?

This would certainly explain why so many different illnesses and trauma (physical and emotional)- from car accidents, to EBV, to Lyme Disease, to Battlefield PTSD – seem to trigger the same constellation of symptoms (and endocrine dysfunction) lumped under ME/CFS/FMS.

Could it be as simple as a certain percentage of any and all trauma/severe infection survivors remain in a state of endocrine disruption as you describe?

Placing it all under the larger umbrella of medical trauma is intriguing…

I agree. For decades ME has been dismissed for lack of a single pathogen or cause. It’s amazing that they are not telling those women in ICU to stop whining and malingering because there is nothing wrong with them. It’s amazing they are not being kicked to the curb. Sounds like progress to me.

The metabolic trap could explain why a certain percentage of people do not get fully well after a severe illness or a needed trip to the ICU. This could cause the whole array of typical symptoms we get in our chronic illness, whether more moderate or severe. Part of the systemic downturn involved does include a lot of endocrine changes and deficiencies. I don’t see these as causative, or remedying them fully curative—they are secondary to the metabolic trap, which I am looking at for now as prime cause. (There is a genetic predisposition, I know, but what sets the whole chronic disorder in motion is the metabolic trap, in my view.) However, bringing up those endocrine levels is very important and can résult in significant improvements. Many of us with ME/CFS or Fibromyalgia do not get this help: a thorough endocrine assessment and augmentation.

The real problem is that researchers focus on various intricate theories rather than simple treatments. As a result patients have to pay enormous amount of money for Valcyte, IVIg, Rituximab etc for nothing. My example shows that the solution may be somewhere else.

In my experience, there is no improvement without immunomodulating treatments. Antivirals and antibiotics are useless because we do not have information on what we are fighting against. Most likely it is a regulatory problem, which is simply utilized by pathogens.

I used GcMAF shot (100ng/week) for 15 moonths. This is available but not licensed. The medication has lots of side effects but after the treatment, 90% of the symptoms dissapeared for 2 years. All my tests turned negative. I was running and worked out in the gym. At the same time, some patients had hairloss and it had the potential to raise testosterone level in female patients. It was withdrawn from the market. What is the lesson: the disease is present but was in remission for years ! Previously, I was unable to sit and failed my bar exam.

A Swedish doctor created vaccine treatment which was effective in CFS. He is sick himself. He used staph vaccine (Staphypan). This was effective but also withdrawn from the market. It cost 10,-USD per month. The theory was to stimulate the immune system and lower its antiinflammatory reactions. Staph was a good candidate for that. We know the reaction of the body to staph.

We are now experimenting with BCG vaccine with the same schedule: 1/10th of the vaccine on week 1, increasing the dose by 1/10th until we reach full dose. Then, we maintain the full dose but use the vaccine only once a month. This treatment is extremely cheap, BCG is a well-known immune stimulant (100 years old) and has antiinflammatory effect. It costs 1,-Eur !

I do not care for Ampligen which cost 3.000,-USD, IVIg wich costs 2.000,-USD per month etc.

Go ahead researchers but we do not have that much time.

Thanks Adam. Looking forward to hearing how the BCG vaccine goes. Good luck with it!

The Staph vaccine disappeared after the company started making it unfortunately.

https://www.healthrising.org/blog/2015/11/21/gottfries-chronic-fatigue-syndrome-story/

I consulted with Prof. Gottfries about this treatment, which has been approved by my petition as off-label treatment by the National Institute of Pharmacy in my home country. I created this protocol myself relying on my personal experiences and clinical research results. Then, I discussed it with the professor. It follows the same logic as Staphypan:

-you need an immunomodulating treatment to which no tolerance can be developed. The human body does not develop tolerance to pathogens. We have to look for pathogens, which elicit TH2 immune response and do not further aggravate inflammation. BCG is an excellent candidate. We start very low and increase the dose incrementally. The compendium of my country knew 30 years ago general immunization with vaccines. I would never experiment with Valcyte or Rituximab when we dont even know the ethiology of the disease. It will not hurt.

You may not recover from this but it can make a meaningful difference without having to pay 2.000,-Eur/month or to wait for another 10 year.

I’ll check back soon. The order for 20 dosages of BCG has been placed. The effectiveness is evident in two months.

BCG and autoimmunity:

https://www.elsevier.com/books/the-value-of-bcg-and-tnf-in-autoimmunity/faustman/978-0-12-814603-3

Protection against inflammatoty and autoimmune disease:

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28532186

BCG vaccine in autoimmune and inflammatory diseases:

https://www.medicaleconomics.com/article/tuberculosis-vaccine-shows-promise-treating-type-1-diabetes-and-other-autoimmune-diseases

Interesting, I’m terrified of vaccines after severely worsening from a flu shot. I actually think it’s the adjuvants they put in vaccines that are the problem for ME/CFS patients. Like you say they shouldn’t aggravate the patients immune system. Does this vaccine have an adjunct?

This is because there is a difference between vaccine and vaccine, the dosage also matters. Prof. Gottfries also investigated various vaccines but none of them produced a result similar to that of Staphypan. He has not tried BCG because it is very difficult to get a licence for that and he is 90 years old. He wanted to file for a licence though. I asked him to send me his proposed treatment and obtained a special permit to use BCG for CFS in my home country.

The dosage also matters. You should start low to make your body it easier to adapt to some degree to avoid excessive inflammation. Then, you raise the dosage and elicit the proposed effect. We will see, I pray for it.

Vaccination therapy is not unheard of in Europe. With the advent of “modern medicine”, vaccine therapy disappeared.

I do not believe in modern medicine though. Medical science became a business.

It might be fairly easy to do a retrospective look at gender differences for those in ICU. If the ICU population neither dying nor getting well is 70-80 percent female like ME, wouldn’t that be interesting.

Women have more complicated immune systems than men. Ours need to be able to shut off in a certain way in order not to attack/reject a growing fetus. More « moving parts » and a capacity for inhibition could provide more openings for « trouble » such as autoimmune illnesses, ME/CFS, and the like.

As an intensive care specialist I have personally treated these endocrine abnormalities in several patients with persistence in muscle wasting and labeled chronically critically ill. Curbing the futile cycle of RT3 is quite important, however I have found that jus applying topical testosterone to the bilateral shoulders daily has profound results in improving lean body mass and overall well-being. This all despite very appropriate and significant protein calorie nutrition support with micronutrients including D3 at levels of at least 60. I do believe that the ICU patient is truly in chronic fatigue with impaired mitochondrial function and a markedly altered autoendocrine axis. Excellent review.

Thanks for providing your experience. 🙂

Dear Dr Friedman,

I’m very glad also to get a positive response from a critical care specialist. Thanks very much! Would you or someone you know consider writing an article on the subject: the relevance of findings from critical care for ME/CFS? Thank you!

Kind regards,

Dominic

Thank you so much, I find this so helpful.

I experienced sepsis during childbirth, then developed Secondary Adrenal

Insufficiency (pituitary based) two years later after a second birth. Then seven years after that developed severe ME/CFS.

These three events seem so connected to me but are often dismissed as related by doctors—particularly endocrinologists I’ve seen.

My last few adrenal crisis hospitalizations escalate in something similar to your described “non recovering” state, taking longer and longer to stabilize on an acceptable long range (vs crisis level) replacement steroid dose. Last one ending up in the ICU.

Your findings fit my narrative so well. I appreciate you sharing on Health Rising.