This sleep series is dedicated to the memory of Darden Burns, a person with ME/CFS/FM, who battled severe sleep issues throughout her illness. Darden took her life after an unexpected relapse left her unable to sleep. Read her story: “To Sleep at Last: A Good-bye to Darden Burns“

“Sleep is the universal health care provider: whatever physical or mental ailment, sleep has a prescription it can dispense.”

The first part of the sleep series uses Matthew Walker’s 2017 book, “Why We Sleep: Unlocking the Power of Sleep and Dreams”, to provide a general overview of sleep.

Walker, a PhD and professor of neuroscience and psychology at the University of California at Berkeley, is in love with sleep and communicating about it – and his enthusiasm shows through in this delightful and well-written book.

The founder and director of the Center for Human Sleep Science at UC Berkeley, Walker is clearly on a mission to wake up America and the world (published in 2017, the book has already been translated several times) to the importance of getting a good night’s sleep. His website is aptly titled, “The Sleep Diplomat“. Walker asserts nothing you can do is more helpful in more ways than getting a good night’s sleep.

“Sleep”, he asserts, “is the single most effective thing we can do to reset our brain and body health each day”. In fact, Walker states that there doesn’t seem to be any organ in the body which does not benefit from sleep (and conversely, which is not harmed by poor sleep).

Getting To Sleep

Daylight / Nighttime

More on melatonin, later, but it’s important to note that melatonin simply provides the trigger for the sleep cycle to begin. It can help get you to sleep but other than that admittedly crucial step, has no impact on how well you sleep.

We know that evolution abhors simplicity – and variations in our degrees of “nightness” and “dayness” exist. “Morning larks” – people who tend to fall asleep earlier in the evening and wake up earlier in morning – really do exist and make up about 40% of the population. “Night owls” – people who tend not to sleep until late in the evening and like to sleep in – are a real thing too, and make up about 30% of the population. The rest of us exist somewhere in between.

Pressure Building

Something called “sleep pressure” actually makes you want to sleep when you haven’t been getting enough. The brain produces a chemical called adenosine which builds up in our brain during the day and is dumped when we sleep. Adenosine turns down the wakefulness-promoting parts of the brain, and turns up the activity of the sleep-inducing parts of the brain.

Because it takes 8 hours of sleep to completely remove this wakefulness-blocking chemical from your brain, many people with chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS) and fibromyalgia (FM) are probably never adenosine-free and thus never fully awake during the daytime. In fact, the author states that a “condition of prolonged, chronic sleep deprivation…results in a feeling of chronic fatigue”.

Throwing these two factors – a chronicity factor and adenosine build-up – together means we naturally reach an energy lull in the early afternoon – a lull this professor thinks we should pay more attention to. Siestas or long mid-afternoon breaks, he believes are extraordinarily healthful things to do.

Our Sleep Cycles

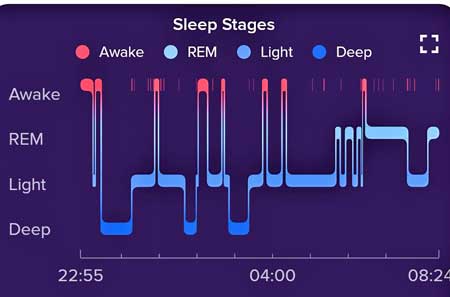

Every ninety minutes, our brains cycle between NREM (deep sleep) and REM sleep – characterized by rapid eye movements. NREM sleep or deep sleep dominates the cycles early in the night, giving way to cycles dominated by REM sleep later. The functioning of this elaborate cycle – more NREM sleep transitioning to more REM sleep later in the night – is dependent, of course, on getting enough sleep. Staying up too late results in a deficit of NREM sleep. Waking up too early results in a deficit of REM sleep.

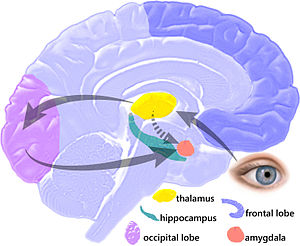

During sleep, the thalamus blocks sensory signals to the brain so that it can attend to other things, such as learning. It turns out that the “sleep on it” adage is a good one.

NREM or Deep Sleep

A characteristic sleep stage pattern showing more deep or NREM sleep earlier in the night and more REM sleep later in the morning.

With its long, slow, perfectly synchronized waves, deep or NREM sleep looks to Walker like “nocturnal cerebral meditation” or the long, slow swells rippling across a placid ocean surface. Emanating from the middle of our frontal lobes (about the middle of our forehead), the swells transfer data from our short-term to our long-term memory stores in the neocortex.

Your ability to remember something from the past day is a function of early night, deep NREM sleep. The vast amount of information we encounter every day means that the flip side of being able to remember something is the ability to forget other things. We simply can’t incorporate it all at once.

During our NREM-dominated late night/early morning sleep cycles, our brains assess the past day’s events and weed out insignificant details. The more relevant data is passed to long-term storage centers to which the REM stage then builds new connections to foster creativity and learning.

The Gist

- The first part of the sleep series uses Matthew Walker’s 2017 book, “Why We Sleep: Unlocking the Power of Sleep and Dreams”, to provide a general overview of sleep.

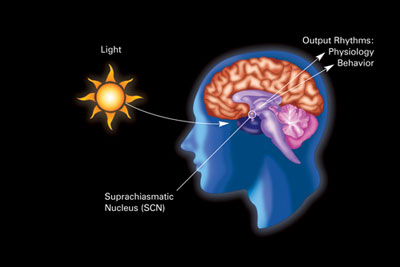

- We sleep largely because of two factors – the suprachiasmatic nucleus in the brain which maintains our circadian rhythms – and something called “sleep pressure” which is triggered by the activation of the sleep centers in the brain by the buildup of adenosine.

- The adenosine is flushed out of the brain when we sleep. Regularly getting less sleep than needed will turn down the brain’s wakefulness regions and activate the brain’s sleepiness centers – leaving one sleepy in the daytime.

- Our brains cycle between deep (NREM) and lighter (REM) sleep. During NREM sleep, the brain transfers significant details of the day into long-term memory stores. During REM sleep, the brain integrates the data into the brain more fully, establishing new connections.

- The old adage “Sleep on it” is actually accurate. Studies show that learning, creativity and even physically mastering tasks are enhanced by a full night’s sleep. These benefits do not occur, though, during poor sleep.

- A nap during the day moves data from short-term storage to long-term storage, replenishing our data stores and our ability to take in information and learn.

- Sleep deprivation results in “micro-sleeps” – short instances when you close your eyes. Micro-sleeps are particularly dangerous during driving. Driving while sleepy is as dangerous as driving drunk.

- Poor sleep affects every part of the body. In the brain, it produces an enhanced fear response and inhibits the pre-frontal cortex in charge of rational thought and planning. Memory and cognition are severely affected.

- Insufficient sleep increases the risk for cardiovascular disease, diabetes, cancer, early death, etc. It reduces our resistance to infections and enhances sympathetic nervous system (fight or flight) activity.

- Insufficient sleep produces brain patterns similar to those seen in mood disorders. Sleep has shown to be disturbed in every mood disorder.

- Insufficient deep sleep prevents the sewage system of the brain – called the glymphatic system – from cleansing the brain of toxins.

- Next up – Pt. II of Walker’s book – dream magic, Walker’s take on sleep drugs, Walker’s suggestions for better sleep.

REM Sleep

Buzzing with activity, on the other hand, the brain during REM sleep doesn’t look like it’s asleep at all. In fact, some areas of the brain are more active during REM sleep than during waking.

During REM sleep, the brain experiences – in vivid color and sound – the past experiences of the day. In order to keep us from acting out our dreams, the brain puts our voluntary muscles on lockdown, leaving you as limp as a rag doll.

It’s during REM sleep that the creative juices of the brain get unleashed, as the brain establishes new connections – which enable new insights to pop up when you wake. Not only can intellectual problems get solved but so can physical ones. During REM sleep, the brain might learn how to properly finger that piano piece you had so much trouble with or help you learn another physical movement better. Studies indicate that practicing a piano piece – plus a good night of deep sleep – improves performance by 20% and accuracy by 35%.

This same process also applies to stroke victims (and, of course, people with ME/CFS and FM). Studies show that sleeping well after a stroke allows the brain to better entrain the new brain connections which will enable one to move again. This is all, of course, neuroplasticity in action.

Transferring the motor memories to brain circuits which operate instinctively – below the level of consciousness – allows a learned skill like playing the piano – once it’s learned – seem natural and effortless. That makes one wonder if some of the movement difficulties in ME/CFS/FM – the awkwardness, the discoordination, etc. – could, in part, reflect poor replenishment of these brain circuits during sleep. Because this type of encoded motor learning occurs during the last 2 hours (of an 8-hour sleep) in stage 2 NREM sleep, most of us – unless we are taking naps – may be missing it.

Naps really do help. Studies indicate that absent naps, one’s ability to learn drops dramatically during the day. Take a 20-minute nap, though, and your ability to learn actually increases by the end of the day. During a nap, the hippocampus uses something called sleep spindles (intense bursts of energy) to transfer data from the day to a long-term storage site in the cortex. With their data stores replenished, the nappers were ready to learn again.

Because these spindles are particularly abundant in the late morning, if you’re waking early may be missing out on this integral process.

Sleep Deprivation

Staying up all night is one thing. Losing a couple of hours of sleep a night for weeks, months or even years is quite another.

Microsleeps – Remember the increased activity of the sleep-inducing areas of the brain that adenosine triggers? One of the consequences of that is something called a micro-sleep – brief periods in which your eyelids partially or fully close – leaving you temporarily blind to the world.

Four nights of 4 hours of sleep each night results in the same number of micro-sleeps as if you had stayed up all night. Carry that on for 11 days and you’re as impaired as someone who just pulled two all-nighters in a row.

The six-hour sleep a night was not all that much better. Ten days of six-hours of sleep a night was like going without sleep for 24 hours.

It gets worse. Ten days of seven-hour sleep – which many of us would probably love to get – left the brain as dysfunctional as if one had been up for 24 hours.

The testing showed that the participants thought they were in much better shape than they actually were.

Micro-sleeps are not such an overt problem – you probably don’t even know they are occurring – unless you’re doing something like driving a car. Less than five hours of sleep a night increases the risk of getting in a car crash threefold. Because you actually temporarily black out during micro-sleeps, driving sleepy is more dangerous than driving drunk. Two million people fall asleep while driving their car every week. Walker goes on and on about how dangerous it is to drive sleepy. If you have to do so, it’s critical to take naps.

Effects of Poor Sleep

Primitive Emotions Take Hold

The biggest effect insufficient sleep had was heightened activity in amygdala – the site of the fear response in the brain.

Feeling hyper-vigilant? Being snappy for no real reason? Irritated or worried about small issues that didn’t use to bother you? You can chalk up some of that to poor sleep. In what Walker called “the largest effect” he’d measured yet, keeping healthy, young adults up all night resulted in a huge increase in amygdala activity and their own personal reactivity. The now sleep-deprived young adults reacted much more negatively to emotional triggers than before. It was as if, “without sleep, our brain reverts to a primitive pattern of uncontrolled reactivity”.

Further studies, which allowed participants five hours of sleep a night, found that the brake pads of the amygdala’s brake – the prefrontal cortex, which studies suggest has taken a hit in ME/CFS and FM – had run low. Without sleep, the prefrontal cortex – the rational, thinking, organizing – part of the brain had trouble reining in an amygdala that was running amok.

Anger and fear weren’t the only emotions running the show. The sleep-deprived participants traveled an astonishing emotional roller coaster swinging from fear and anger to “punch-drunk” giddiness. It was as if reducing their sleep had knocked them off their emotional center. One of the more dangerous emotions encountered during these dramatic mood swings was depression, including suicidal depression. Studies now show that sleep disruption in adolescents is associated with increased suicidal thoughts.

Besides aggression, suicide and insufficient sleep is also associated with addiction. In fact, in a stunning statement, Walker reports that “there is no major pyschiatric disorder in which sleep is normal”.

Psychiatrists have assumed that mental disorders lead to sleep issues but Walker’s lab has demonstrated that lack of sleep can, by itself, produce neurological patterns in the brain which mimic mental disorders. Many of the brain regions most impacted by poor sleep are the same ones impacted in mental disorders.

Walker does not assert that mental illness is caused by poor sleep but he does argue that the role sleep disruption plays in our emotional well-being has been underappreciated and underutilized diagnostically and therapeutically. Indeed, instituting behavioral practices that improve sleep in people with mood disorders has proven beneficial.

One group of depressed individuals stands out like a sore thumb. About a third of people with depression do better with less sleep – possibly because their mood swings swing them toward happiness instead of anger, etc.

Learning

As noted earlier, a lot of learning takes place as the brain moves the day’s data for short-term storage to longer-term data storage and integration sites in the brain. It turns out that sleep deprivation stops the flow of data from short to long-term storage in its tracks.

Because this activity occurs during deep sleep, anything that disrupts deep sleep and keeps someone in shallow sleep prevents the learning process from taking place. Plus, anything that does stick, doesn’t tend to stick around. Recent studies indicate that even our short-term memory storage center – the hippocampus – is affected, indicating that sleep deprivation impacts even short-term memory retention.

Rodent studies indicate that imprinting new information – and one must assume that probably includes doing neuroplastic exercises to change how your brain works – is really difficult when you are sleep-deprived.

Sewage Backing Up

The 2012 discovery of the glymphatic system in the brain helped to answer a problem that had long puzzled researchers: just how does the brain, absent a lymphatic system all its own, get rid of toxins. It turned out that the brain has a glymphatic system (and, it turns out, a kind of lymphatic system – discovered in 2015, as well). The glymphatic system consists of small channels between the glial cells which collect and send waste products out of the brain.

The catch – the glymphatic system only operates during our very deepest sleep stages. If you don’t get deeply asleep, your brain won’t get its nightly roto-rooter cleaning. As you descend into deep sleep, your brain does two weird things. First, the amount of blood in the brain drops – clearing the way for the cerebral spinal fluid to reverse and move upwards into the large ventricles at the base of the brain – presumably to collect the waste products produced by the brain during the day.

Because Alzheimer’s patients have long been known to have problems with sleep – particularly deep sleep – researchers conjecture that their inability to cleanse the brain of toxins may play a role in the disease. Walker noted that depriving mice of deep sleep leads to an immediate increase in amyloid deposits in their brains. (High aggregations of amyloid deposits in the prefrontal regions of Alzheimer’s patients’ brains are associated with deep sleep loss). Walker suggests that identifying and treating sleep disorders early may help delay or even stop the onset of Alzheimer’s and dementia.

My father may have been a case in point. We all knew he had sleep apnea for years, but he refused to get tested, and eventually died of Lewy Body Dementia.

Metabolism

We don’t know what’s causing the exertion problems in ME/CFS and FM but whatever is causing them is not being helped by the poor sleep. Getting less than 6 hours of sleep results in a 10-30% drop in aerobic output and sets us up for a metabolic breakdown which sounds very much like ME/CFS/FM: increased lactic acid build-up, reductions in blood oxygen saturation and increases in two exercise-induced toxins (lactic acid and carbon dioxide) are all associated with poor sleep.

With the body in a kind of cardiovascular, metabolic and respiratory breakdown, it’s no wonder that studies show a huge increase in injury in athletes with chronic sleep issues – and longer recovery times as well.

“Every major system, tissue and organ of your body suffers when sleep becomes short.” Matthew Walker

Walker notes that more than 20 large epidemiological studies have tracked the effects of sleep – or the lack of it – on people over many decades. The decidedly uncomfortable conclusion for sleep-deprived ME/CFS and FM patients – the shorter your sleep, the shorter your life.

The stats are astonishing. Adults 45 or older who sleep less than 6 hours a night are 200 percent more likely to have a heart attack or stroke during their lifetimes. (This is probably due to increased blood pressure – which doesn’t seem to be such a problem in ME/CFS/FM.) Five to six hours of sleep a night makes you 200-300 percent more likely to suffer from calcification of the arteries over the next five years.

“Through this central pathway of an overactive sympathetic nervous system, sleep deprivation triggers a domino effect that will spread a wave of health damage throughout your body”. Matthew Walker

The main driver of this death and destruction is one we’re well aware of – the sympathetic nervous system. Studies by Ute Vollmer-Conna in Australia tightly link the sleep dysfunction in ME/CFS to the SNS. (More on that in a later blog).

Insufficient sleep has also been linked to increased rates of type II diabetes, weight gain (hunger pangs, increased snacking), reduced testosterone, altered gut microbiome, reduced resistance to infections, and several cancers.

“It doesn’t require many nights of short sleeping before your body is rendered immunologically weak”. Matthew Walker

During this time of coronavirus it should be noted that a study found that people sleeping five hours a night were almost 3 x’s more likely to catch a cold when exposed to a common cold virus than people sleeping seven hours or more. Even the effectiveness of a flu shot can be impacted. Even healthy, young people – when restricted to four hours of sleep a night – derive only a little immune boost from a flu shot.

Genetically, poor sleep boosts the production of genes associated with inflammation and cellular stress.

Dying of Poor Sleep?

Since sleep affects virtually every system in the body, the question arises whether you can actually die of poor sleep. The answer to that question is: yes. Thankfully, it occurs only very, very rarely.

In a rare genetic disorder called fatal familial insomnia, a mutation in the prion-related protein (PRPN) gene causes misfolded (and toxic) prions to build up in the thalamus, damaging the nerves there.

Like some other genetic disorders, this one doesn’t show up until middle age, but when it does, it manifests with a vengeance. The disease begins with a rapid onset of insomnia which steadily gets worse until after a couple of months, sleep becomes completely impossible and the person dies.

- Next Up – Pt II – Dream Magic, Walker’s Scoop on Sleep Drugs and his advice on getting better sleep.

- Check out Walker’s beautiful Center for Human Sleep Science website.

Can you correct poor sleep with a sleeping pill?

Great question! I’ll cover Walker’s answer to this in more detail in the next blog. I was shocked at his answer.

I have been suffering with insomnia about 30 years. (i’m 62 now). trazadone helped me for many years. But now nothing has helped even though i’ve tried lots of different sleep medications. They usually make me wide awake. which doctors can’t understand. Sometimes i go many, many days with no sleep or a few hours. i’m so exhausted i just lay in bed all day. i am very desperate for help. thanks for any and all help.

Thank you for that beautiful diversion; Cycle. I noticed that there are more similar, the next is called Diffusion. Later I plan to look for others…

Now regarding sleep, as I have mentioned, I am trying to tame my ME/CFS with Levothyroxine plus additional supplements. I’m in the midst of titrating up my dose and am noticing better energy and some modest improvement in other hypothyroid symptoms–but am still not back to ‘normal.’ Still have PEM.

I’m taking the Levo in the P.M. and I noticed that I completely flipped my sleep cycle from owl to lark–and not intentionally! Also I added two multi-ingredient supplements (to promote better adrenal/thyroid function) and after the first dose, I once again started having vivid dreams which I now can remember. Since I started both supplements at the same time, and each has a number of ingredients, I’m not sure which to credit this new effect.

Since I have tried most of the ingredients separately at one time or another, I can only suspect the effect is from ones I have never used. Those would include small amounts of parotid, thymus adrenal and spleen bovine extracts.

Despite being a tiny bit nervous taking these extracts, I am extremely pleased I can now enjoy my dreams. I used to be able to log and ‘map’ my dreams, similar to an actual mental landscape. With intention I could sometimes ‘will’ myself to return to a particular location to continue with a dream on successive nights. And very rarely, I could experience a lucid dream, which means they are very much like waking reality–until you discover they are not. Some are not too far from normal reality and others are quite strange. Some are predictive, some healing, and others provide answers.

Cort, you may get into these topics in Part 2. Personally, I think having the intention of remembering and entering the dreamworld, which is one of the great frontiers, could potentially unlock many of life’s mysteries. I also see how much the body responds to the will of hormones–and in unexpected ways–so thank you for posting this!

I also have vivid dreams. Have since childhood. I’ve read that it’s related to chemical imbalances in the brain. I was reminded just last week that I have to be EXTREMELY careful with supplements as well as meds. I got a different brand of magnesium, which made me feel anxious…Didn’t realize til I was refilling my weekly supplement boxes that it contained Vit B3 which I had noticed in the past (by default, when I quit taking extra B vitamins) made me feel anxious and agitated. I have quite a list of meds and supplements that elevate my blood pressure and pulse. Didn’t monitor my vital signs this time, but was running hours short on sleep (I generally need 10 hrs/ nite), felt agitated, had racing thots and was verbally hyperactive. That can be SO embarrassing as I just blurt out whatever goes thru my mind and it comes out jumbled up sometimes.

I am taking from this that we should throw ‘everything but the kitchen sink’ at trying our best to improve our sleep – even with ME!

This is very timely, given the current stresses about COVID-19.

No kidding – my sleep has significantly deteriorated over the past week. It’s showing up not only in my poor sleep scores but in my increased heart rate at baseline which is up from a low of 63 to 70 bpm.

I can really feel the difference.

I have lapsed into a bad week long sleep cycle. Never knew how badly the sleep cycles could affect my me/cfs/fm until I got the Oura. I can see a definite pattern. Yesterday I was so ill that I felt the next layer would be death. I other words so sick it couldn’t get much worse. Then today I read this article on sleep and know I am on the right track. My resting heart rate is up, my temp has been elevated which I felt last night before bed. It was as if my body was so ill, trying to recover caused all sorts of issues. Oura really layed the law down this morning.

I love Matthew Walker. And I really liked that book when I first read it. But there are problems worth noting as well…https://guzey.com/books/why-we-sleep/?fbclid=IwAR1VaK3qwQMIInkI0cYSaJC4-rMFa6HDqb4SNPmvh8QpX6dg1uuHkm0vxFg. Everyone can make a mistake, but the ones that border on scientific misconduct are deeply concerning for a scientist of his caliber. I don’t know how he can fix this, short of drastically revising the whole book. That said, there’s a lot in there on sleep hygiene especially that holds up. His two episodes on Peter Attia’s podcast were also excellent (if problematic for the same reasons as the book).

That’s quite a tome by Guzey. I would note though that Walker’s book is hundreds of pages long, and Guzey cites just six errors if I’m reading him correctly, the second of which (that some people with depression do better with less sleep) he acknowledges that Walker writes about.

Another of which – that “Lack of sleep can kill you” regarding “fatal familial insomnia (FFI)” – note the name – I would give Walker a pass on.

Guzey may be right about sleep duration not declining over time. A 2016 study found no association between sleep duration and year over time – https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26478985/?from_term=patterns+of+sleep+duration+last+50+years&from_pos=1. On the other hand, Guzey cites a paper which states “However, the evidence for increasing sleep deprivation comes from surveys using habitual sleep questions.” which indicates there IS evidence for reduced sleep levels over time.

While the WHO organization didn’t say a sleep epidemic is occurring, their funded studies have – https://www.researchgate.net/publication/230593124_Sleep_problems_an_emerging_global_epidemic_Findings_from_the_INDEPTH_WHO-Sage_Study_among_More_than_40000_Older_Adults_from_8_Countries_across_Africa_and_Asia – and the CDC has actually called sleep issues a public health epidemic – https://www.sleepdr.com/the-sleep-blog/cdc-declares-sleep-disorders-a-public-health-epidemic/

Some of Guzey’s points seem a bit pedantic. Take this one – Walker writes

Guzey provided the National Sleep Foundation’s sleep recommendations:

Adults (26-64): 7-9 hours.

Of course it would have been more accurate if Walker had said 7-9 hours and I couldn’t find WHO recommendations either; Walker said an average of 8 hours – which is what you get if you average 7 and 9. I think Walker did blow it a bit here – people should know that 7 is OK too and that 9 is as well. He’s a bit sloppy here but not inaccurate.

Guzey has found some issues but if you look at the rather exhaustive level of detail he’s gone into, I don’t know if finding that number of problems in a book of that size is that big of an issue.

Hi Cort,

Thanks for reading my post. I’m a bit puzzled by you writing: “I don’t know if finding that number of problems in a book of that size is that big of an issue.”, given that I explicitly state in the beginning:

“Any book of Why We Sleep’s length is bound to contain some factual errors. Therefore, to avoid potential concerns about cherry-picking the few inaccuracies scattered throughout, in this essay, I’m going to highlight the five most egregious scientific and factual errors Walker makes in Chapter 1 of the book. This chapter contains 10 pages and constitutes less than 4% of the book by the total word count”

Cort, what a terrific article, on such an important matter! Looking forward to part 2.

Thank you!!

Strangely, I have the sense that it takes energy to sleep well, not that sleeping well gives me energy. Does anyone else feel that way?

I actually don’t know since I never sleep well – but it makes a weird kind of intuitive sense to me.

It does in fact take energy to sleep well. Just as it takes energy to think — think well, think hard, study, etc.

They say the brain uses some large percentage of the ATP produced by our body. During sleep, memories are being stored, “clean up” work is being done . . . lots of work is going on.

Our bodies may be quiet and still, but our brains are buzzing.

Basically what I’m trying to say is that the insomnia from which I suffer is the result of a lack of energy in my body, not the other way around as is commonly experienced by healthy people. I think this is so for 3 reasons:

1. Even after what I feel is good, deep sleep, I can still feel very fatigued.

2. My insomnia developed after my chronic fatigue, not before.

3. I once took ubiquinol and began to feel more energized. Subsequently, my sleep improved.

Thanks Tim. My sleep issues only emerged after ME/CFS/FM as well. Interesting about the ubiquinol. 🙂

Tim, I seemed to get more stamina when I started taking ubiquinol/CoQ10. I made three changes at the same time – a Herculean effort to calm down, get better sleep and started taking the CoQ10, so it’s hard to be precise.

However I definitely felt an improvement not only in my sleep but also at some fundamental energy level. As in, I could use some energy and I didn’t then almost immediately run out. I still take it everyday.

I’ve had an herbalist say that very thing to me.

Clementine, what thing?

Along with many other things, I can’t handle ANY stimulants including caffeine. Co-Q 10 is even too much for me as is Ashwaghanda (don’t know it that’s even considered a stimulant…)

Thank you Cort for an informative piece on sleep. I’m looking forward to part 2! Huh, sleeping a max of 4hrs at a time makes for frightening consequences. No wonder my short term memory is so poor! Reading and concentrating on such articles also makes my head hurt, probably too much detritus in my brain ? Better hurry and get my affairs in order!

There have been many times that the sickness completely disappeared and I felt recovered when I wake up after 4-6 hours of deep sleep. I go back to sleep again, and the crushing fatigue and ache would return when I get up in the morning. Most of the times though, sleeping is the worst time. I literally quake with ache and fatigue under the comforter as if I’m suffering from a severe flu. I call it feverless feverishness.

There must be something going on in the brain while you sleep that alternatively makes CFS better or make it worse.

I’ve noticed this exact same thing. I wake up early – my body feels OK – go back to sleep and the achy muscles return. Not all the time but sometimes. Something happens early in the morning.

I experience something similar. I wish I could find out what’s causing it, so I could do something about it. Sub-conscious stress may play a role, but I feel something else might be happening, too, and I can’t figure out what (and so-called “sleep specialists” have been no help). It’s interesting to see that others are experiencing this same thing. I wish we could get some answers. Apparently, I do have “mild” apnea, but I don’t think that’s necessarily the answer. Grr…..

Improving the quality of my sleep has been an absolutely crucial and fundamental part of my increasing wellbeing. I can’t stress that enough.

Not so long ago I was completely lost in a downward spiralling labyrinth and I couldn’t find a way out. I was exhausted, couldn’t think straight, couldn’t remember anything, my sleep was fragmented and my stress levels were chronically stratospheric. I was becoming intolerant to most food – I just couldn’t find food that gave me energy without a backlash of some sort – resulting in even less energy.

I had no notion of having a recognised illness until I came across Dr Nancy Klimas. I then trawled around the internet and found Dan Neuffer. I just watched his videos and interviews with people who had made some sort of recovery (not necessarily with his program).

As I had zero memory and terrible brain fog, it took a while for the message to sink in. I had to somehow bring my maelstrom of a life into some sort of order and get better sleep.

So what I did was forcibly put all my stressful issues to one side and just thought – Well I’ll just have to pretend everything’s ok – even if I have to lie to myself – I honestly didn’t care. Anything to try and break the vicious circle I was caught up in. I wasn’t even totally convinced it would work but that didn’t matter – I just had to try it because I was getting worse and I knew it.

Much to my surprise and enormous relief it actually worked. I could feel the difference after that first night of better/deeper sleep. Straight away I could tolerate more food. That was almost a year ago.

Since then I’ve made a steady improvement. I decided that if I could just make a bit of progress over a year, that would be better than the precipitous decline I had been on.

For me my stress response is very closely linked to the quality of my sleep. So is the food I eat.

I think when I managed to at least make some improvement, I felt a bit more empowered. It was terrifying to be so completely out of control and have no idea how to get out of it. Not to mention that other people thought I was making the whole thing up…

So what I tried to do was bring some sort of semblance of order to my life. I would try and get up and go to bed at the same time, eat at the same time etc. Get my circadian rhythm back in line. There was one day, when I’d had a sleep in the day and then got up and drove the car but realised, to my horror, that part of my brain wasn’t awake! So, night time was for sleeping and I could have a short nap in the afternoon but that was all.

I read the article by Guzey but I don’t think we should be distracted from Matthew Walker’s message. Walker isn’t on his own in his beliefs. Dr Nancy Klimas says the same kind of things in her video from 2014 – MECFS Treatment Options Part 1 with Dr Nancy Klimas.

She says : ‘Most patients with chronic fatigue syndrome have non restorative sleep and that comes from a lack of deep sleep, which is called slow wave sleep in the sleep clinic’.

Dr Klimas goes on to say that ‘a lot of chronic fatigue patients also have, or develop over time, sleep apnea’. However she believes that ‘it could be very dangerous with people with apnea, to put them into a deeper sleep’. So people need appropriate treatment.

Also a group of people wrote an article called ‘Interactions between sleep, stress, and metabolism: From physiological to pathological conditions’. Camila Hirotsu, Sergio Tufnik, and Monica Levy Anderson

In their Abstract they write:

‘Poor sleep quality due to sleep disorders and sleep loss is highly prevalent in the modern society. Underlying mechanisms show that stress is involved in the relationship between sleep and metabolism through hypothalamic (HPA) axis activation’.

All very relevant to me. Now I still have food intolerances, difficulty with medications and many chemicals/perfumes. But with the better sleep and calmed stress response at least I have a base from which to work from. My memory and brain function have much improved. My energy is far more reliable. I still have to monitor how I am but I now approach the day with less fear that I’m not going to make it to the other end… ?

My daughter saw a Perrin Technique osteopath for a little over a year. She went from moderate with occasional dips into severe, out of education, basically bed bound most days, to now being back at school, recently able to take a school trip to Berlin, pretty much no restriction on activity. I talked about sleep with the osteopath at the beginning of the journey. Daughter had great difficulty falling asleep and would wake again and again through the night and I could see this was a huge part of her problem. Osteopath said that sleep returning to normal is always one of the last things he sees. Consistently. And this was the case with us. She made improvements in lots of other areas but it was only right towards the end, a year after beginning, when she had made huge strides towards recovery, that the sleep piece fell into place. And we tried all kinds of things to help. The sleep dysfunction seems to be one of the most difficult to tackle, but also a real benchmark of improvement. I get very nervous now when daughter tells me she had a bad night’s sleep. Very worried the nightmare might be starting all over again.

I’m 70 and even as a very young child, I would stay up most of the night reading. While I was working I averaged 3 to 4 hours sleep a night and many times was up 2 to 4 days in a row due to being on call. Being sleepy in the daytime was never an issue until this past year believe it or not. I was diagnosed with CFIDS in 1999 and was injured so badly in 2004 I had to stop working. Anyway over the last year I have become almost totally non-functional by afternoon I won’t even drive. I find myself falling asleep in the recliner which has never happened before. Even with CPAP and oxygen at night I’m lucky if I sleep 4 hours. It’s really starting to get to me because I’d like to know why all of a sudden I need sleep LOL.