Fatigue has been a mystery to the research world. Take multiple sclerosis (MS) – one of the most fatiguing diseases known. Fatigue is often one of the first symptoms that shows up in MS and it’s often the most troubling symptom MS patients experience, yet the fatigue in MS isn’t associated with the nerve lesions that cause the movement and other problems found in the disease.

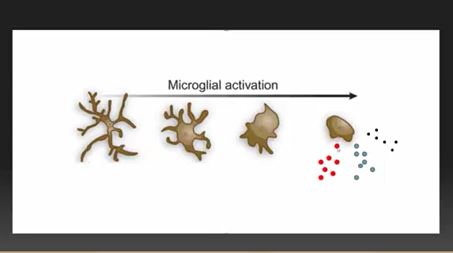

The study authors proposed that microglial cell activation was causing the severe fatigue found in multiple sclerosis

Despite the lack of correlation between nerve lesion damage and fatigue, fatigue worsens as the disease progresses. It’s clear that several parts of the brain are affected in MS – the location of the lesions (usually in the supratentorial and perivenular areas and around the spinal cord in the neck) – and somewhere else.

Recently, Anthony Komaroff pointed to a possible fatigue center in the brain, elucidated by a multiple sclerosis study. The fact that the study, “Regional microglial activation in the substantia nigra is linked with fatigue in MS“, came from a now pretty familiar location – Harvard’s Brigham and Women’s hospital – which Ron Tompkins, David Systrom and other ME/CFS researchers are associated with – highlights again how useful it is to have ME/CFS researchers embedded in major medical centers.

This was kind of a hybrid hypothesis-driven exploratory study. Since all we know for sure, regarding the fatigue in MS, is that it’s not coming from the nerve lesions – the study needed to be exploratory. The study authors, though, had a hunch: microglial activation and the neuroinflammation it was causing was producing the fatigue. That idea, of course, fits right with similar speculations regarding ME/CFS/FM.

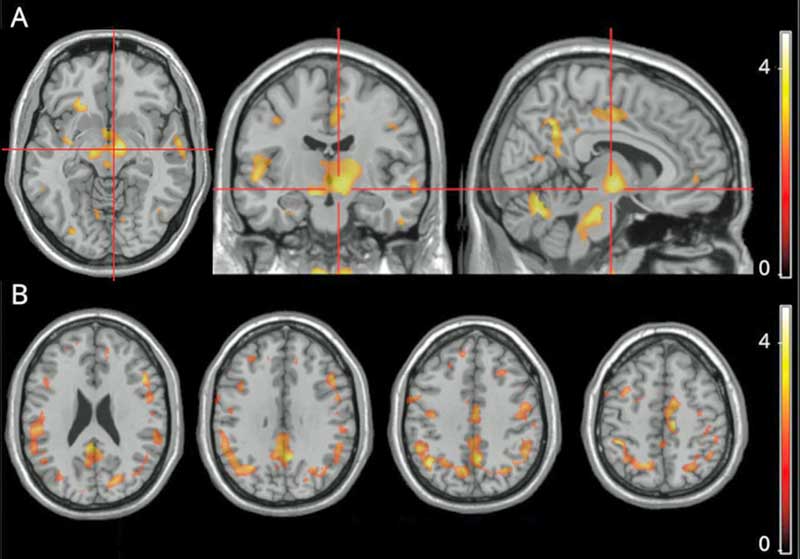

Because the site of the neuroinflammation was unclear, Medical Express reported that the researchers used what they called a “snooper” – a PET scan which used a radiolabeled “detective” or tracer ([F-18]PBR06 radioligand) to bind to activated microglial cells. This was the first time microglial activation was assessed with regard to fatigue in MS. Not knowing where to look, they looked everywhere – and their finding, from an ME/CFS perspective, anyway – was astounding.

Results

The bright spots reflect correlations between fatigue and microglial activation. The bright spots in the middle are located in the substantia nigra of the basal ganglia

The main finding was a “strong correlation” between the amount of fatigue the MS patients were experiencing and the activation of microglial cells in a part of the brain called the substantia nigra. Secondary analyses found microglial activation in other parts of the brain (right precuneus, parahippocampal gyrus, putamen, thalamus, juxtacortical white matter) were also associated with increased fatigue.

All in all, the authors reported finding evidence of “widespread” microglial activation in the brains of MS patients with high rates of fatigue. Both Younger’s and Nakatomi’s ME/CFS study, and the recent fibromyalgia study, found evidence of “widespread” neuroinflammation as well.

The Basal Ganglia

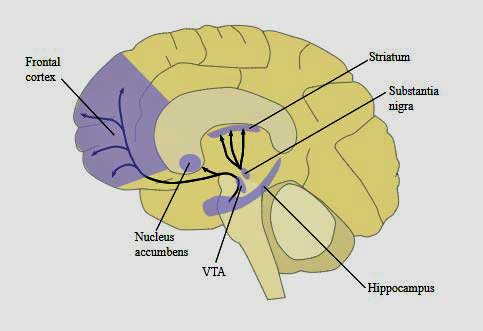

The substantia nigra is part of the basal ganglia – a set of structures in the midbrain which affect “reward”, fatigue and movement. Damage to one part of the substantia nigra is responsible for the movement problems in Parkinson’s disease. Without the substantia nigra, we couldn’t (subconsciously) “plan” movement – an essential part of being able to move at all.

The fatigue in MS isn’t totally mysterious – we just know that it isn’t associated with the amount of nerve damage present. Other studies have suggested that microstructural changes and abnormalities in various connections, networks and structures play a role, and several hypotheses (dopamine, neuroendocrine and functional disconnection) have been formed.

The cause behind these abnormalities has never been identified, but these authors proposed that the microglial activation they found could be the “unifying mechanism” driving the structural and other changes.

More pertinently for our case, though, they also suggested that the microglial activation might simply be causing fatigue in general – and jumped right into chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS).

A Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS) Connection?

Given the similar findings in ME/CFS, I had been wondering, hoping, praying that ME/CFS findings would make their way into this paper and they did – in spades – a good sign that ME/CFS findings are getting around.

First they cited the 2014 Nakatomi ME/CFS neuroinflammation study. Then came Chaudhuri and Behan’s mammoth 2004 paper, “Fatigue in Neurological Disorders“, which proposed basal ganglia dysfunction was causing the fatigue in ME/CFS, and then came Komaroff’s 2019 JAMA paper, “Advances in Understanding the Pathophysiology of Chronic Fatigue Syndrome“, one of the top visited papers from JAMA of 2019. They even cited a 1998 paper which compared post-polio syndrome to ME/CFS.

Findings suggesting that the activity of the default mode network was altered in more fatigued MS patients provided another potential connection between ME/CFS and fibromyalgia. One study in ME/CFS and many in FM have produced similar findings.

Miller’s 2014 Basal Ganglia ME/CFS Study

ME/CFS studies were thankfully well-represented. The authors didn’t cite, though, Andrew Miller’s 2014 study which explicitly linked reduced basal ganglia activation with fatigue in ME/CFS.

Miller, a psychoneuroimmunologist, came to his basal ganglia work in ME/CFS via a fascinating route. It turns out that giving an immune factor called interferon-alpha to hepatitis C patients knocks down their infection, but also produces an ME/CFS-like state (fatigue, fever, and other flu-like symptoms) in a large subset of patients.

Notice the concentration of dopamine in the midbrain (basal ganglia and hippocampus) and the prefrontal cortex. The Japanese believe dopamine reductions in these areas are producing fatigue in ME/CFS

It was the ability of interferon-alpha (IFN-a) – which is naturally produced by the body – to do this which clued researchers into the phenomena of “sickness behavior”; i.e. the deliberate production of symptoms to keep people with infections immobilized.

After studies suggested that this “sickness behavior” is being produced by the basal ganglia in hepatitis C, Miller used a functional MRI (fMRI) to measure the basal ganglia’s response to “reward” in ME/CFS patients and healthy controls.

Miller used “reward” because hepatitis C studies have shown that “reward” is strongly associated with fatigue, our mood and, interestingly, how well we move and react. In that vein, it’s interesting that ‘psychomotor’ slowing – one of the most consistent findings in ME/CFS – is also commonly found in people with basal ganglia dysfunction – and is also highly associated with fatigue severity.

Miller found that mental and physical fatigue and reduced activity in ME/CFS was correlated with reduced activation of the globus pallidus (GP) in the basal ganglia (BG). Reduced input from the striatum in the basal ganglia was also found.

The Gist

- Severe fatigue is one of the most common symptoms in multiple sclerosis yet is not produced by the nerve lesions characteristic of the disease.

- Proposing that microglial activation and neuroinflammation might be causing the fatigue M.S. researchers did an amall open-ended PET scan of the brain

- They found widespread evidence of neuroinflammation with a hotspot located in one a part of the basal ganglia called the substantia nigra.

- Located in the midbrain the basal ganglia is involved in “reward”, movement, sleeping and wakefulness and others.

- Researchers first learned of the connection between the basal ganglia and fatigue when hepatitis C patients given interferon alpha to fight their infection developed ME/CFS-like symptoms such as severe fatigue and other flu-like symptoms. Those patients were found to have reduced basal ganglia activation.

- Since then reduced basal ganglia activity has been associated with fatigue in MS, ME/CFS and other groups.. Numerous studies have documented basal ganglia problems in ME/CFS, fibromyalgia and Gulf War Illness.

- Low levels of dopamine, the main neurotransmitter serving the basal ganglia, can result in even small actions requiring large amounts of effort.

- Miller’s findings suggest that low levels of dopamine may result in a hypersensitivity to inflammatory factors. (It was the hepatitis patients with low dopamine low levels who developed severe fatigue, etc. after taking IFN-a.)

- A good deal of evidence suggests that dopamine levels may be low in fibromyalgia and could be contributing to the pain hypersensitivity found there.

- The authors proposed that a microglial activation in the basal ganglia could be producing fatigue in a number of diseases including ME/CFS and urged more studies be done.

- Finding a common “fatigue nucleus” in ME/CFS and other diseases would be a huge step forward.

A Dopamine Connection?

That reduced input, Miller thought, was probably indicative of an under-functioning dopamine system. In fact, Miller suggested that problems with reduced dopamine functioning might be found across the brain in ME/CFS.

Dopamine plays a pivotal role in the regulation of mood, motivation, reward, motor activity (movement), and sleep-wake cycles. Low levels of dopamine can result in high levels of effort being needed for even simple tasks.

Miller proposed that low dopamine levels may also have an insidious effect that leaves the central nervous system vulnerable or sensitive to inflammation; i.e. that suggests low levels of inflammation – perhaps the kind found in ME/CFS and FM – could cause high levels of fatigue, motor slowness, cognitive problems, etc. Studies suggest that when given IFN-a for hepatitis C, it’s the dopamine-deprived individuals suffer who suffer from enormous fatigue, motor slowing, and depression. Dopamine deprivation, then, could possibly set the stage for an ME/CFS-like reaction to an infection.

Since Miller’s 2014 paper, the connection between damage to the basal ganglia and ME/CFS-like symptoms has only strengthened in hepatitis C, ME/CFS and allied diseases.

Just a year ago, a study linked fatigue and perceived stress with inflammation and altered connectivity between the basal ganglia and the insula in hepatitis patients treated with IFN-a. Another 2019 study linked fatigue in these patients to microstructural changes in the striatum – another part of the basal ganglia.

Thapaliya’s 2020 study found microstructural changes in the basal ganglia in ME/CFS. Low putamen activity was associated with fatigue (and low reward) in Japanese children with ME/CFS. A huge (880 person) Japanese study found that increased fatigue and reduced “reward” was associated with three different structures in the basal ganglia.

Wylie’s 2019 study implicated the basal ganglia in fatigue in Gulf War Illness (GWI). While a 2018 review of fatigue and the nervous system couldn’t come up with a definitive region of the brain, the basal ganglia and the limbic system were two of the four brain areas highlighted. Plus, reduced basal ganglia functioning was associated with increased physical fatigue in older adults.

Other researchers are hovering around this area. Japanese researchers have proposed that an inhibited circuit involving the prefrontal cortex, the basal ganglia and other structures stops signals going to the motor cortex to increase muscle performance.

Barnden’s fascinating study suggested that microglial activation in the midbrain and prefrontal cortex teams up to produce the autonomic nervous system and sleep problems in ME/CFS.

Dopamine, the Basal Ganglia and Fibromyalgia

Several studies implicate reduced dopamine in fibromyalgia as well, and one fMRI study also found the same reduced levels of reward found in ME/CFS and IFN-a patients. Connections to pain have cropped up. One hypothesis proposed that reduced brain reward circuit functioning plays an important role in determining our levels of pain sensitivity.

Other studies found reduced dopamine metabolism in FM, reduced brain dopamine uptake, and one study suggested that reduced dopamine levels are associated with increased pain sensitivity in FM.

Treatments?

Conclusion

Another unifying hypothesis – this time for fatigue and possibly even for neurological disorders – microglial activation and neuroinflammation

Fatigue is one of the most common and disabling symptoms of MS, yet it is not, oddly enough, related to the lesions which cause the movement and other problems in the disease. Some studies have found brain abnormalities that are associated with fatigue in MS, but it’s never been clear what’s causing them. A small exploratory MS study may have provided an answer – microglial activation and neuroinflammation.

As in ME/CFS and FM, widespread areas of neuroinflammation in the brain were found in MS. It was the key finding of the study, however, that aroused the most interest. The part of the brain most associated with the fatigue in MS was the substantia nigra of the basal ganglia. Damage to the basal ganglia has long been proposed to play a crucial role in the fatigue in ME/CFS and other diseases, and the authors readily cited past findings in ME/CFS.

They didn’t cite, though, the 2014 Miller paper which found that increased mental and physical fatigue and reduced activity was correlated with reduced basal ganglia activation in ME/CFS. Since Miller’s study, several others have implicated the basal ganglia findings in ME/CFS and FM. Other researchers are focused in on the prefrontal cortex/basal ganglia/hypothalamus connection. There’s more “there there” in this area all the time.

Miller also highlighted dopamine – a hormone/neurotransmitter – which plays a critical role in reward, motor activity (movement), sleep and wakefulness, mood and possibly pain. Low dopamine levels can make even small activities fatiguing.

Miller’s studies suggest that low dopamine levels may sensitize the basal ganglia to inflammation – causing fatigue, flu-like symptoms, etc. even when inflammation levels are low. Several studies suggest that low dopamine levels may also be contributing to the pain and other symptoms found in fibromyalgia.

These studies suggest that microglial activation could be contributing to reduced basal ganglia activation and fatigue not just in ME/CFS and FM, but in MS and other diseases.

Some researchers – including these MS researchers – believe that microglial activation lights the fire that produces central nervous system diseases like MS, as well as other diseases like Parkinson’s disease, ME/CFS, FM and GWI. The type of disease that is produced depends on the where and how of the neuroinflammation and the environment; i.e. the biological construct of the individual involved.

Has a fatigue nucleus that operates in many different diseases been found? Finding out that the fatigue in MS, ME/CFS, FM and other central nervous system diseases are caused by similar processes would be a huge boon. Finding out that neuroinflammation is at the heart of all of them could be an even bigger boon. That might suggest that anything that tamps down neuroinflammation in one disease might help in another – and lots of efforts are being made in other diseases to find ways to reduce neuroinflammation.

Given that it was good to see the authors emphasize that future research studies search for “common…mechanisms of fatigue” in neurological disorders such as MS, ME/CFS and Parkinson’s disease.

“Future research studies are needed to compare the fatigue-related microglial changes in MS with other diseases such as CFS and Parkinson disease and identify common and disease-specific mechanisms of fatigue in neurologic disorders.” The authors.

Thank you Cort

Has anyone found any success in treating low dopamine levels? How have they done this?

There are references to using Abilify to raise dopamine here

https://www.healthrising.org/blog/2020/10/03/celebrating-whitney-dafoe-awakening-37th-birthday/

Here is another older link.

https://www.healthrising.org/forums/threads/whitney-dafoe-and-ativan-can-someone-explain.6018/#post-37218

Way back in 2011, I was wondering about Dopamine, mostly D2. Some of my old post on this above link, questioning it.

Ive been able to raise my chronically low dopamine by increasing BH4 (tetrahydrobiopterin) by my doctor prescribing Kuvan. It does not have the negative effects that Abilify does.

Ha! That’s the substance that Miller suggested.

Did you insurance company pay for it? What were your symptoms and how did it help. What dose and how long to notice effects?

How do you know that your dopamine is low? How were you tested? Thanks for sharing!

I’d love to try Kuvan but have no access. I therefore combine tyrosine with 5HTP.This combination increases availability of BH4 for metabolism of tyrosine to dopamine by reducing the need for BH4 for the metabolism of tryptophan to 5HTP .

I’m using Korean Red Ginseng now to up dopamine. And some food grade terpenes to balance neurotransmitters and they do other things ( antiviral, antiinflammatory, antibacterial, etc). So far, so good. (Elevation Terpenes)

Before, Tramadol was my best medicine all around. It works on all the neurotransmitters and I took tiny, tiny doses and cycled on and off. Along with a very mild muscle relaxer , called Bentyl, some of the time. (Mostly off those now. But keep in reserve for very bad POTS days.)

Bacopa also is another help and in a brain supplement I use for brain fog. And has been talked of a good bit to help ME/CFS.

I did at one time try Velvet Bean, but couldn’t get that regulated. Since the research Dejurgen did on dopamine, may had been too much dopamine causing a build up of dopal which becomes a bit toxic.

I personally found a need of and connection with dopamine to oxytocin. A need to also increase this.

Balance is key.

Thanks for the Ginseng recommendation.

I would add for other readers that Tramadol is an opioid, with all the associated risks for addiction, and long term use increasing pain sensitivity.

I’m in the UK and suffering mild-moderate CFS/ME (more fatigue/brain fog than pain)

I am soon to start LDN (prescribed privately by an Endocrinologist) to raise my ‘endorphins’ – does that mean Dopamine will be raised too?

I’m not recommending it, but I vape nicotine. Calms down the nervous system and gives me the ability to focus.

I’ve tried dopamine supplement with no luck. But Sudafed or Bronkaid seems to bring some measure of relief. Stimulants are known to be dopaminergic. I once thought it must be either stimulant or vasoconstriction, but now I think it’s the dopaminergic effect that is more likely.

A few years ago one of my doctors prescribed me Provigil. It helped me so much but my insurance wouldn’t pay because I would have to be diagnosed with sleep apnea. I couldn’t afford to pay for it myself. I think I’ll try what your doing.

Thanks for this excellent summary, Cort. Does Abilify impact the neurotransmitters cited here in a way that is consistent with the helpful effect that it is having for some people?

My guess is yes, but these brain circuits are so complicated. It’s only a guess.

Dear Cort, I don’t know how you can be so prolific on so many subjects . I wish you get out of ME/CFS and get your Nobel prize!

I have to concur. Thank god for you netting all this myriad of info for sufferers, families if sufferers and doctors alike

I agree! But please stay with us in CFS!!!

Thanks! I always feel like I’m way behind actually…

You always bring me so much hope! Thank you for your dedication and hard work.

Ditto, ??? to Cort.

Also, Alzheimer’s falls into the dopamine deficient group:

https://www.google.ca/amp/s/www.medicalnewstoday.com/amp/articles/321372

I still wonder if Alan McDonald, with his findings on neural nematodes and also his findings on neural spirochetes,

(especially in light of his work with slices of brain tissue from people diagnosed ith MS)

will one day be recognized for having been ahead of his time on a major cause of brain inflammation.

Thanks, Cort for synthesizing all of this research!

1) Has anyone looked into using Boswellia or curcumin to reduce microglial activation and brain inflammation?

2) Has anyone looked into the effects of increasing tetrahydrobiotrin to increase dopamine? When I told my specialist I had increased energy from the prescription of Kuvan, He knew about it but thought it was too difficult to get a prescription for it, but meanwhile it increased my energy by 30% as well as increasing my chronically low dopamine to high normal levels.

3) Has anyone looked into using hyperbaric oxygen therapy to reduce microglial activation and brain inflammation?

Thank you!

Yes on trying Boswellia and Turmeric with Curcumin. I felt the herb Turmeric was better than the concentrate from it. But for whatever reason, I didn’t keep using it. (Still cook with it. And put it in coffee with ginger some.)

Boswellia, be very careful with. If you have Lyme or any pathogen issues. I had one of THE worst herx with it. Thought I had a ruptured disk. Finally after seeing a spinal doc, we discovered it was a herx that hit my back. Worked as a type antibiotic. I’ve been afraid to try that one again. I did feel it initially helped though.

Tyrosine is also supposed to help up dopamine. That was not a very good experiment for me either. But helps some.

Kuvan is a treatment for PKU, Phenylketonuria, also called PKU, a rare inherited disorder that causes an amino acid called phenylalanine to build up in the body. PKU is caused by a defect in the gene that helps create the enzyme needed to break down phenylalanine.

Without the enzyme necessary to process phenylalanine, a dangerous buildup can develop when a person with PKU eats foods that contain protein or eats aspartame, an artificial sweetener. This can eventually lead to serious health problems.

For the rest of their lives, people with PKU — babies, children and adults — need to follow a diet that limits phenylalanine, which is found mostly in foods that contain protein.

Babies in the United States and many other countries are screened for PKU soon after birth. Recognizing PKU right away can help prevent major health problems. (Mayo website info)

If Kuvan is helping some patients with ME/CFS, I wonder if the PKU diet would be helpful as well.

I have been reading about this and it is connected to BH4 dysfunction. What Moira suggested with 5HTP and Tyrosine, seems to get the BH4 Pathways to work more correctly when/if this is an issue with phenylalanine. And it will balance out low dopamine and issues with nor-epinphrine. It is the same pathways connected to glutamate. The 5HTP would help balance out seratonin.

With my 23&me genetic testing, I learned of methylation issues and BH4 is one of them.

I had a horrible life threatening MCAS response (Kounis Syndrome) to aspartame in having too much sugar free gum. Thats how I figured out about glutamate issues.

And have had issues with having too many animal proteins. Was a vegan for years, but got too weak and went back on animal proteins, but still limit them.

I guess I need to try to address this better than I have. And learn more……

Dopamine, heck yeah. In my daily journal, ‘zero-dopamine today’ has been the most recurrent phrase. I’ve relied on ‘Robot Mode’ to get me moving, not always successfully.

I have found that a ketogenic diet helps, plus a fasting regime. It seems to reduce inflammation and bring back a bit of brain & reward.

Fasting and very low carb have been useful to myself as well to allow minimal functioning. I would like to know just why this is the case.

Good piece.

I understand another Japanese paper on microglia activation and CFS is due this year.

Let’s hope – as it’s supposed to be a greatly expanded study. A positive finding there would make a huge difference.

Could everyone please be very careful when thinking of raising their dopamine levels. Too much dopamine causes psychosis.

That is true and also dopal, which can be very toxic.

With the medicines that Whitney is on, it can both increase and decrease dopamine. But it is a serious medicine. It can also cause death. So nothing to take lite.

Imbalance neurotransmitters, by upping one too much and you throw the others off. Can be a very risky thing to play around with. And having doctors very well educated to help with this, is a real good idea!!!!!!! Even then, it is hard to get it correct.

To give the short summary of what is discussed in the blog Issie linked:

Dopal is one of the break down products of dopamine. It is toxic at, if I recall well, 1000 lower amounts then dopamine itself.

There are IMO good indications that the break down of that very toxic dopal is inhibited in many ME patients, meaning we would easy get higher levels of this toxic stuff then healthy people. Increasing dopamine without deep knowledge could increase the amount of this toxic byproduct to dangerous levels.

It can permanently destroy neurons and motor neurons in particular. It also can temporarily inhibit them very strongly, possibly causing strong PEM like effects. Too much dopal is thought to be a potential big problem in nasty diseases as Parkinson and even ALS if I remember right.

This post has Dejurgen going pretty deep into dopamine and its by product dopal. We don’t want that to get too high.

https://www.healthrising.org/blog/2020/06/05/fight-flight-neuroinflammation-fibromyalgia-chronic-fatigue-syndrome/

I wonder if anyone has considered things like ritalin or adderall in low/moderate doses to improve dopamine levels and relieve many of the issues described in this paper. My relief from chronic fatigue could be largely attributed to these stimulants along with the usual assortment of other therapies. I do have other diagnoses (ADD-PI, and Narcolepsy), for which ritalin or adderall are a common remedy. These drugs are stigmatized, but life changing for those who need them, including myself. This may be the case for many with CFS, it seems but I’m no expert.

Wellbutrin and other medications are available as well. They apparently target dopamine to a lesser extent.

Been sick for over 40 years. I started Modafinil (Provigil) one year ago. Started with 25 mg and am now on 50 mg (normal dose is 200 mg a day). It has made the world of difference for me and I am wondering if it is because it increases dopamine? I am hoping it is safe to continue taking.

I considered, but those stimulants are relatively expensive and require prescription. Sudafed works for me though, at least partially. I happen to have eustachian tube dysfunction, so it kills 2 birds at once.

I have same echastian tube defect & sinus pain ,seems to trigger my flare up

Nothing seems to work ,is all these comments relating to medications for fatigue or the painful episodes in facial area. ?i hsve bad brain fog & cant read too much

I would urge everyone on here to look very deeply into Neuroendocrine likely benign tumors from Schwannomas, Messenchymals even an insulinoma of the pancreas…

My friend had a schwannoma removed from her Brian & another friend she had a messenchymal found in her heel, yes her foot by the NIH she had (TIO) Tumor Induced Ostomelacia she has like me a pituitary benign tumor she also has

osteoporosis as well this tumor in her heel is robbing her bodies calcium & these tumors are not easy to be found. I was diagnosed today with bowel Cancer which is also a neuroendocrine tumor now they are going full body scans looking for all

neuroendocrine tumors. NIH told her that her 2 surgeries from Eagle Syndrome the calcified bone was highly likely caused by TIO/messenchymal she had both sides removed…One can have normal levels of phosphate/ALP or low/high with this tumor

the scan is the key to diagnosis & other tests…If one has a benign NET Tumor found you can be Cured…

@Adian, sooooooo sorry to hear they found cancer with you. Sure hoping it was found early and they don’t find any other tumors. Good you have been so diligent with your searching and getting more answers. Hoping the best for you! Please keep me posted on the PM, if you like.

Issie

That cancer diagnosis sucks. Sorry to hear that.

All I can say is: the best of luck with your treatment! May all go well.

I have been sick with CFS and Fibromyalgia for over 40 years. Neurontin (600mg a day) and Elavil (7.5 mg a day) have helped marginally, but nothing has worked as well as Modafinil (Provigil) which I began a year ago. I started at 25 mg. and am now at 50 mg a day (normal dose is 200 mg a day). Initially I could not believe how much clearer my mind was and how much steadier my energy was. It says that one of the side effects is insomnia, but it actually has helped me sleep better, possibly because I have so much more energy during the day. My health improvement has gone from a 2 to a 5 (on a scale of 1-10). Possibly it works for me because it increases dopamine levels.

Issie, try combining tyrosine with 5HTP. Tyrosine on its own depletes BH4 levels leading to an increase in oxidative stress levels.

Thank you Moira. Been taking 500 mg of Tyrosine, in the a.m. for a few years now and no longer getting the expected benefit. Will add 5HTP!

@Moira, seems that combining the two makes it a good combination. I’m not using a full amount of either. But going low and slow. So far, I think there is some benefit from it. I stopped my other things that work on those pathways, to make sure it would be just that as the effect. Thanks for the clue on this. Was the one thing with my methylation I had not addressed. And may be a really big part of my puzzle and a nice “purple bandaid”. We will see. Thanks again!

On tyrosine, appears using more than a Pinch caused issues with mast cell. Upped the dosage over last 2 days and it hit me hard today. I knew I couldn’t use it before. So seems, with me, it built up. Had high hopes for this one. Will give it a break and try again, to see if it is this or just a couple of not so good days.

@Moira, Thanks, tyrosine on its own was a no go for me. And I do have BH4 issues.

Linking this blog (fatigue/microglial activation/ dopamine/ BH4) with the RAS system (recent blogs): High AngII levels impact BH4 levels.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5357050/#!po=13.7363

Fascinating article as ever, Cort. Thank you for all the remarkable work you do here. When referring to fatigue, are we also talking about post-exertional malaise (which to my understanding is specific to ME?) or is that a separate entity and via a different mechanism?

This suggests that limiting inflammation is key. Diet is an obvious, and safe, place to experiment.

I’ve had success with finally doing an elimination diet, followed by the Wahls protocol (originally for MS).

I have long resisted doing the grueling elimination diet, but eliminating my allergens has so far mitigated most of my “awful days” (where my fatigue feels like all my cells are being ripped apart in slow motion.) The book the Plant Paradox gave me insight into what food types to focus on eliminating.

So, an encouraging word to try the elimination diet! What you find may surprise you. It can give you answers like whether or not your body can handle a vegetarian diet.

Has anyone else had success on the Wahls Protocol?

Hi Jessica, yes I would be aware of the Wahl’s protocol – I was just writing a reply to you on my phone and had got quite a long way and then my brother called me and I lost the lot. Will try again!

Okay in short, as I’ve already written this and lost it – this is my world – brain inflammation.

Now no one else thinks this, apart from me because obviously as an ordinary person, I couldn’t possibly be smart enough to know my brain can be inflamed.

However being a contrary sort of character – I think – well I know where my brain is located and I know it can become very irritated and then doesn’t work properly, which is not good.

I think I may have had Swine Flu (H1N1) in 2017. I was already unwell and this just made things much, much worse. So when I went to my doctor and said – could you give me something for my brain inflammation, he smiled at me and shook his head. Obviously yet another over-reacting, anxious, middle aged woman.

So, I was on my own. I was already aware of the functional medicine crowd and from them – people like Dr Mark Hyman, Dr Datis Kharrazian, Dr Terry Wahl’s etc, I put together what I wanted to work towards – a modified low carb, Mediterranean diet.

It was very much a trial and error approach as I react badly to many foods. I take a number of supplements too, such as a multivitamin and mineral, which is high in the B vits, Bit C, Omega 3, Digestive Aid, Magnesium, CoQ10, Migrea probiotic by BioKult and Psyllium. I also add Apple Cider vinegar and extra virgin olive oil to my poached eggs, kale, spinach and grass fed meat. I drink Rooibos tea.

I have found that as I calm my stress response and get better quality, restorative sleep – I can then tolerate more food.

I found that eating chocolate gave me energy – it sort of lit up my whole system – and that was a relief because I realised that I wasn’t actually broken – I just hadn’t found the right fuel.

I have been eating choc chip cookies too, which stopped me feeling faint, nauseous and my heart racing. I know they’re not a good thing and the packaging is desperate. However I think two things were happening – they raised my dopamine levels, which kick started my whole system into a higher level of functioning and I think the salt and sugar may have been helping to rehydrate me and in particular, my brain. They do however, raise my level of inflammation, so I’m trying to wean myself off them. I’ve found that as my level of general functioning improves, I can eat some salted peanuts, which may be able to replace the choc chip cookies.

Anyway fascinating topic, thanks Cort! I’m going to go without scrolling up to check this, as again, I’m on my phone and the battery is getting low and if I lose this I’ll cry…

I forgot to say that I sprinkle Turmeric and Ginger on my food too. I also initially found Ibubrofen helped calm my brain down, which indicated that what I was experiencing was inflammation – not easy to decipher when your brain is dysfunctional. However my immune system didn’t approve of the Ibuprofen and vetoed it’s use. If I did take it my heart rhythm would be affected and that’s really not good.

Hi Tracy Anne,

Your reply really resonates with my experience. A big issue that I’ve struggled to adjust to is the brain fog. Actually, it’s less that I’ve struggled and more that others just dismiss it as “old age” (I’m only in my 30s!)

I’ve had M.E. for over 20 years now, but it was only 6 years ago that I began focussing on my diet. A friend recommended that I try following the blood type diet and I haven’t looked back. To begin with, it has led me to almost entirely eliminate processed foods which I believe can be no bad thing.

From the foods you list, it sounds like you’re eating the same as me already! Naturally the food list varies according to blood type, but I wouldn’t discourage anyone from trying it. There’s science behind it too (for those who are interested: https://www.dadamo.com)

I hope this is useful to someone 🙂

Hi Kathleen, that’s so great that you found something that helps. For years I just wanted someone to find out what was wrong and then fix me. It took a very bad reaction to some maize starch ‘hidden’ in some low fat mayonnaise (low fat/high carb!) – I think my blood sugar dropped very low. I then realised I needed to stop being so casual and get focused.

Food is a fundamental part of my own health promotion plan. I also had a massive problem with stress, which triggered an immensely powerful stress response, which then wrecked my restorative sleep, which then had a knock on effect on my immune system and I became more and more intolerant of most food.

My stress response was fired up and the flames were fanned by the intense isolation and oppression I felt, as no one would believe me. I felt judged and at times persecuted – others were patronising, dismissive and disrespecful.

Anyway, luckily I found answers myself, through reading books and watching the functional medicine cohort – online.

I’ve also learnt so much from Cort’s blogs, people’s comments and from Solve M.E.’s webinars and the Open Medicine Foundation’s Symposiums.

The Medical Profession in general, have not been helpful and I would personally perceive them as being immensely oppressive.

I know someone that had interferon treatment for hepatitis C and was not right for a few years after. Major insomnia, cognitive dysfunction ( memory, processing, vocabulary) and then recovered to normal health. It was a few more years until they developed ME/CFS.

Certainly is interesting to learn of studies linking the interferon treatment, inflammation and various conditions. Seems like these findings should lead to studies looking at ways to treat this inflammation. Are there any underway or planned?

Microglial activation is also implicated in concussion fatigue. There was a paper that claimed 40% deactivation by in vitro injection of turmeric. I tried a supplement since I didn’t have access to in vitro injection, but that didn’t work.

There are other ways to promote dopamine other than through drugs. Over the years I noticed I could do twice as much without triggering PEM when visiting family members, traveling or on a high alert. At least one other patient reported a similar experience. If enough patients show similar response, maybe that’ll point to a direction for more research.

Here is the paper that I posted before. It reports that dopamine down-regulates activated microglial cells. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6141656/

I think I get what you mention TK – that if you were ‘visiting family members, traveling or on high alert’ – you could do twice as much, without triggering PEM.

What I am trying to avoid, is the feeling that my brain has turned to sediment, because if I get to that stage then I think my system is not functioning efficiently and I am running on the dregs of energy and that doesn’t do me any good and I’m exhausted and depleted.

However if I’m a bit more fired up, then it feels as though I’m running a bit cleaner. As long as I don’t over do things and keep going on false energy ie too much nervous/wired energy then I do okay.

I feel I’m on the up at the moment and it feels sustainable and just about understandable.

I do think for me anyway, dopamine seems to be involved. I think we all come to Health Rising with our own particular dashboard of issues – mine appear to be around immune, stress response and brain energy issues and probably others I can’t remember at the moment…

Back when I was still highly physically active and in a pre-ME state or maybe even mild ME, I used to get involuntary movements in my upper arms and shoulders. Like minor spasms. They occurred spontaneously when I was not moving and sometime when walking.

I also have noted how my signature has declined over the years. It’s not the typical change where our brains just take shortcuts and the signature process itself becomes automated and more efficient. It’s become harder to control my hand. I’ve noticed that the sequencing of the movements is out of sequence and the timing is way off. Whether I try harder to control it or I just relax and let it be automatic, my hand initiated changes in direction of its own accord and the result is letters of uneven size and various strokes started before the preceding stroke has finished.

It’s interesting to see research highlighting potential causes and also hinting that there might be ways to reduce the inflammation.

Interesting article Cort – another piece in the puzzle that seems to indicate raised microglial activity linked to neuroinflammation within the limbic system/ hypothalamus and mid brain (including substantia nigra) can account for the wide range of symptoms in ME/CFS.

#STAYHEALTHY

#STAYSAFE

Hello TBI, Concussion and Stroke Survivors. Thanks to GOD & Ryder Trauma Center / Jackson Memorial Hospital I am grateful to be alive. While listening to tbi Music lovers I do my daily therapies LoveYourBrain YOGA-Bike/Elliptical/Walk as I am grateful to be alive.

I am Marcelo Vidal and use to work at Pistils & Petals in Miami Beach ,FL and had my second night time job working on Venetian Lady Yacht Charters doing fabulous weddings and private parties for the rich and famous. Unfortunately on 10/17/15 this high speeding driver did not stop on his red light and crushed me in my car until firefighters arrived with, “Jaws of Life” rescued me out to board me on a Blackhawk helicopter owned by Jackson Hospital were I was airlifted to Ryder Trauma Center / Jackson Memorial Hospital were I laid in coma for 29-days and stayed hospitalized for 6-weeks recovering from a fractured leg and Traumatic Brain Injury, TBI《5-INCH HEAD SCARE》.

What saved my life was wearing my seatbelts as I am grateful to be alive. I was released home wheel chair bound and Doctors thought I would never walk, talk or even comprehend again from my Spinal Cord Injury and the 5-inch Head scare I have across my head until Brain Injury Association of America☆FLORIDA☆ and Spinal Cord Program authorized therapy at American Pro-Health Physical Rehabilitation Center and by the Grace of GOD and the excellent therapy given to me there within 8-months I can walk, talk & comprehend.

By this time I was cleared to do Aquatic Therapy with Kelly Gomez Messett from Jackson Health System Recreation Therapy Neuro Group and had an awesome time swimming in an Olympic pool because I am grateful to be alive.

While I continue seeking Adaptive Rowing Therapy at Miami Beach Rowing Club I would enjoy the beautiful south Florida weather as a crack of smile appears on my face knowing how Thankful and Grateful I am to be alive. During all this time till present day I have sessions with my Neuropsychologist Dr. Susan Ireland from the 5-inch Head scare I have across my head that gives me constant pounding headaches with hallucinations, fatigue and anxiety and I can not take any medications because it intensifies my hallucinations so Dr. Ireland taught me this breathing counting exercise a form of meditation that has taken all my symptoms away as I enjoy watching and listening to Amy’s TBI Tribe | Concussion & Brain Injury, Faces of TBI, The Brain Health Magazine, Brain Injury Awareness Brain & Life Magazine, Traumatic Brain Injury Survivors, Brain Chat, Brain Injury Support Group of Duluth, Brain Injury Advisory Council – BIAA, I CARE For Your Brain with Dr. Sullivan group, Impossible Dream Catamaran, The Woody Foundation, Dharma Yoga Studio, TBI Hope & Inspiration, Post Concussion Support-real support for all Concussion Types, Level 10 Hope Exchange, TBI Survivors and Caregivers Support Group, TBI One Love, TBI Family of the World, TBI Support & Awareness, Traumatic Brain Injury Healing & Recovery Support Group,, Traumatic Brain Injury Support,, Traumatic Brain Injury Healthy Alternatives and Strive Recreational Therapy Services to better understand myself and others living with Traumatic Brain Injury, TBI and share it at PEER and Caregivers Neuro Support GROUPS every last Wednesday of every MONTH from 6:30pm-8pm hosted by Kelly Gomez Messett from Jackson Memorial Hospital with FREE-parking, snacks and water for TBI, Concussion and Stoke Survivors as we share and discuss TBI, Concussion and Stroke Awareness Support for survivors as I am grateful to be alive.

Congratulations Marcelo and thanks for sharing your progress. It’s amazing the progress that can be made now. I would note that a physical therapist in the Dys International conference reported that the protrocols for post-concussion and traumatic brain work very well for people with dysautonomia and POTS.

Good luck with your continued recovery. 🙂

I meant to say that I have Dr Peter J. D’Adamo’s book Eat Right for Your (blood) Type. And the rest… Having brain, gut, immune and energy issues (I will have forgotten some – I always do!) I have circled around the people who deal with these kind of issues and then picked out the bits that seemed helpful to me.

This was meant to be a reply to Kathleen above…

This is a very interesting connection. There is clear evidence that dysfunctional astrocytes play an important role in disease progression in MS. Indeed researchers (lately, also clinicians) use a biomarker for astrocyte dysfunction to gauge neuroinflammation in MS: GFAP (Glial fibrillary acidic protein – can be measured in the blood).

With all the talk about neuroinflammation and glial dysfunction in ME/CFS I wonder why GFAP hasn´t been looked at in ME/CFS as of yet (antibodies against GFAP have been examined in GWI, they do play a role there and they have also been found in a subset of M/CFS patients: https://www.mdpi.com/2076-3425/10/9/610