Paul Garner’s recovery story from long COVID has met with almost universal dismay and anger from the chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS) community. Garner, after all, was something of a champion for long COVID and ME/CFS. An infectious diseases specialist who had weathered serious infections before, he seemed perfect for the job of validating both long COVID and ME/CFS.

Paul Garner (from Linked in)

Then he published his recovery story, “Paul Garner: on his recovery from long covid“, using behavioral techniques, and the whole thing collapsed. Hundreds of comments demonstrated the ME/CFS community’s dismay. The champion had suddenly turned, for a community seeking, above all, more research funding, into something of an enemy.

The upset was understandable. The fear is that such a public figure’s recovery story will blunt in the U.K. the recent newfound openness to biological inquiry. I hope it won’t. The U.K. has gone down the psychological/biopsychosocial rabbit hole for many years. Does it really open up that can of worms again? Hopefully not.

If anyone has embraced mind/body approaches, it’s been me. That’s in part because the only really significant thing that’s moved the needle on my illness was the EST training in the early 1980s. Since then, I’ve tried these again and again with limited results. While they can be helpful I don’t see them as providing anything close to the viable community-wide approach to this illness that we need.

The answer to ME/CFS and long COVID has to come from science, and in that regard Paul Garner’s recovery story presents something of a problem. Is it really incompatible, though, with what we know about the biology of the brain? Perhaps not.

Explaining Paul Garner

Most of the comments on Garner’s recovery story are focused on finding fault with it or rejecting it in some fashion. My focus here, though, is trying to explain it. The first thing to look at, in attempting to do that, is at who Paul Garner is.

Garner is an infectious diseases specialist who was one of the original creators of the Cochrane reports. He helps lead a network of over 300 people who synthesize research on tropical infections to inform global, regional, and national policies. He works with the World Health Organization and developing nations across the world. Over the past almost 20 years, he’s co-authored somewhere around 100 publications. In other words, he’s a very successful, hard-working, well-respected professional.

Plus, he’s personally dealt with serious infections like malaria, dengue fever and others. If anyone could calmly wait out an infection – it would be Garner. Not only has he personally experienced a boatload of serious infections, he professionally deals with them all the time. All of this suggests that Garner’s illness couldn’t be the result of an aberrant emotional response – that’s just not who he is.

Yet here he is – being very emotional:

“I became obsessive as the months passed in an attempt to avoid my symptoms. I started unconsciously monitoring signals from my body. I sought precipitating causes. I became paralysed with fear: what if I overdid it? I retreated from life.”

Garner’s illness had him become physically and emotionally discombobulated in a way that none of his other infections had. That’s saying something quite significant about the sheer strength of his illness. It also suggests maybe an emotional destabilization of some sort might have been part of the disease experience.

“A vicious cycle is set up, of dysfunctional autonomic responses being stimulated by our subconscious.”

Many people have objected to this statement above, and I do too, but perhaps for a different reason. Here, Garner suggests that the subconscious is driving the disease experience.

Is it possible, though, that Garner simply had a form of sickness behavior? That his symptoms were produced by the brain to cause him to conserve his resources and keep an infection from spreading. The sickness behavior response is not just physical – it’s mental and emotional as well. It causes the brain to produce symptoms, thoughts and feelings that lead one to isolate ourselves and spare the community our infection. Could the subconscious impulses Garner referred to be part of this sickness behavior response?

“Sickness behavior is a coordinated set of adaptive behavioral changes that develop in ill individuals during the course of an infection.[1] They usually, but not always,[2] accompany fever and aid survival. Such illness responses include lethargy, depression, anxiety, malaise, loss of appetite,[3][4] sleepiness,[5] hyperalgesia,[6] reduction in grooming[1][7] and failure to concentrate.[8] Sickness behavior is a motivational state that reorganizes the organism’s priorities to cope with infectious pathogens.” From Wikipedia

Paul Garner – Earlier in his illness

Look at Garner’s own words: “I retreated from life”. A “retreat from life”, of course, is the essential goal of the sickness behavior response. Until this pandemic came along, we’ve forgotten what a scourge infectious illnesses (bubonic plague, polio, syphilis, malaria, cholera, tuberculosis, HIV/AIDS) have been in our past. They’ve easily caused more death and suffering than any other factor over time. Our bodies are primed to react to them with all means possible – and that means physiological and emotional responses.

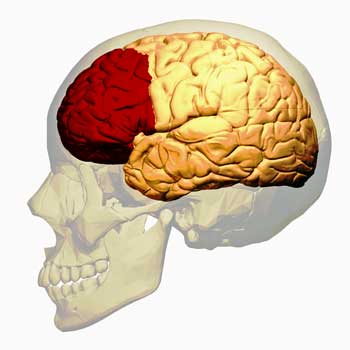

In the brain, the autonomic nervous system is also heavily intertwined with organs that regulate emotions. The fact that the brain organs most often implicated in ME/CFSFM are all associated with autonomic nervous system function, emotions and pain and sensory processing, suggests that all three are in play in these diseases.

- Insula – involved in emotions, motor control, cognitive functioning, pain processing, and the autonomic nervous system, movement.

- Amygdala – autonomic nervous system regulator, sensory stimuli processor, center of the fear response.

- Anterior cingulate cortex – autonomic nervous system regulator, stimuli and pain processing, emotional regulation.

- Prefrontal cortex – coordinates autonomic nervous system, neuroendocrine and behavioral responses to stress, seat of executive functioning.

I should note that when I think of Garner, I’m trying to explain myself as well. I know that along with my autonomic nervous system issues (difficulty settling down, poor sleep, I believe poor energy), have come problems with focus, making decisions, fear, irritability and anger.

For years I’ve asked myself: where this fear and subclinical anxiety comes from? Why is it so difficult to settle down? Why do little things bother me so much and affect me physically so much? My guess is that this is, at least for me, part and parcel of a disease process that affects the two major stress response axes (ANS, HPA axis) , the metabolism, and the immune system. It could all be the result of an ongoing, brain induced sickness behavior response.

Notice, though, that the fact that Garner was living in a state of fear didn’t help at all. If anything, it made everything worse. It amplified his fight/flight response leading to increased pain, depleted energy, poor sleep, and a Th2-based immune response that likely left him less able to fight off pathogens and more susceptible to allergic/mast cell reactions. His parasympathetic rest-digest response was turned down as well- resulting in fewer opportunities to heal.

The Prefrontal Cortex to the Rescue?

“ME/CFS is a stress response disease.” – Nancy Klimas, 2014 Nova Southeastern Conference

Several hypotheses have been put forth in the ME/CFS literature which could, I think, potentially biologically explain how Garner got better.

The prefrontal cortex regulates sympathetic nervous system function, the cardiovascular system, sensory inputs, and the emotions. Could Garner have rehabilitated it?

The Japanese have found that as healthy controls became more fatigued during extended cognitive tasks, the parts of their brains involved in mental processing begin to disengage. Two core regions, in particular, the prefrontal cortex and the anterior cingulate cortex, shut down.

As these regions begin to shut down, they begin to lose control of the autonomic nervous system – in particular, the parasympathetic or “rest and digest” nervous system. One of the main jobs of the PNS (parasympathetic nervous system) is to calm down the sympathetic nervous system and, indeed, studies suggest that the PNS is underactive in ME/CFS.

The Japanese believe the prefrontal cortex (PFC) may be the key. The prefrontal cortex is an amazing, multidimensional brain organ. Not only does it regulate the PNS, but it’s also at the heart of “executive functioning” – which refers to reasoning, planning, judging, etc. It also regulates sensory inputs (physical sensations, over-stimulation), emotions (high emotional lability), attention span, working memory, planning, self-control and decision-making – none of which, at least in my experience, are doing particularly well. Plus, the PFC also appears, via the PNS, to regulate the cardiovascular changes occurring during movement.

The Japanese have found damage to the prefrontal cortex in ME/CFS. They believe that with the inhibitory brake of the prefrontal cortex gone, the sympathetic nervous system has been let loose, causing the brain to react to the slightest stimuli, leaving people with ME/CFS agitated, wired and tried, with distorted immune systems, etc.

It’s possible that the techniques Garner used helped him rehabilitate his prefrontal cortex. Studies show that meditation and mindfulness can increase prefrontal cortex activity and reduce the activity of other areas of the brain such as the anterior cingulate, which have been implicated in increased pain. The ability of mindfulness techniques to reduce pain is well known. Plus, garner’s decision to stop constantly assessing his symptoms could have taken some load off of his sympathetic nervous system.

Once Garner got his prefrontal cortex back in shape, his sympathetic nervous system may have calmed down, his immune functioning may have returned to balance, the blood flows to his muscles became more normal, etc.

Broken Gates

A similar idea is that instead of properly filtering out sensory information, broken gates at the brainstem and spinal cord are allowing too much sensory information through, whacking the amygdala, insula, anterior cingulate cortex and other regions of the brain with tremendous streams of stimuli – and leaving them in a state of alarm.

In this scenario, finding ways to strengthen the prefrontal cortex allows it to calm down the fight/flight response, thus improving the immune response, possibly improving cardiovascular functioning, etc.

Wirth and Scheibenbogen have not endorsed stress reduction techniques, but one part of their hypothesis suggests an overly activated sympathetic nervous system is clamping down on ME/CFS patients’ blood vessels. That stops them from feeding enough blood to the muscles, thus forcing the muscles to rely more on anaerobic energy production. They propose that the body attempts to compensate for that by producing vasodilators such as bradykinin, which cause pain and fatigue.

In this model, finding ways to reduce the stress response could be helpful as well.

Something Wrong

Garner said that the “pure biomedical explanations felt wrong” to him, but there’s something about Garner’s recovery which feels wrong as well. Unlike some, I believe Garner did recover using the means he did, but there was something about it that was all too easy.

Anyone trying to project Garner’s recovery story to all the long-COVID patients and/or ME/CFS community is going to run into some significant problems.

Garner Was Already Getting Well

“You were very lucky. Many, if not most, people with PVFS recover within two years. To extrapolate this to ME is a bit of a stretch… you were already statistically in the group most likely to recover (having been ill less than a year).” – Comment on Garner’s blog.

Some people have pointed out that Garner was in a kind of a recovery sweet spot. He was at a point in his illness when if someone is going to get well, it was probably then. The prevalence of severe fatigue in the Dubbo studies dropped about 30% from six months to 12 months (12%-9%). I believe it dropped to about 5% over two years.

It’s possible, then, that Garner was already getting well and misattributed his recovery to his behavioral approach. It’s also possible that he was slowly getting better and his behavioral approach accelerated that process.

In general, for me, I tend not to put too much faith in coincidences. If someone starts a program and they notice results, I tend to assume that the results are coming from that program. Still, it’s possible that Garner was on the road to recovery and this program accelerated that.

Been there – tried that…

“Yet there are people who have tried the very same things as Paul Garner and not recovered, suggesting it isn’t as simple as he suggests.”

“I was initially diagnosed with ME/CFS as a 15 year-old elite athlete. I subscribed to the biopsychosocial model and spent 6 years using various cognitive approaches, and obviously exercise (as a top level footballer), however, nothing worked.”

“Many with ME have tried the strategies you vaguely explain, often multiple times, and ended up the same or sicker…”

“…suddenly my mind over matter push through didn’t work. I tried multiple times, and stubbornly each time crashed worse than the last until I was mostly disabled and unable to find a path back. I’ve tried various ‘brain retraining’ protocols, herbs, TCM, rx’ed meds, etc.”

“One is that variations of this approach have been around for a long time. If this technique led reliably to a recovery, there would by now exist convincing evidence showing this.”

It’s not as if people with ME/CFS avoid the approach Garner took. Many approaches to ME/CFS focus heavily or partially on mind/body techniques (Amygdala retraining, Lightning Process, Alex Howard, DRNS, ANS Rewire, MBSR, CBT/GET). Many people have tried these techniques and some people do get better (and some people get worse), but there’s no indication that these approaches reliably lead to recovery.

Garner Was Never as Sick as Many of Us

This is certainly true. Many people have comorbidities and complications which Garner didn’t have. Some people have been ill for decades. Many are more functionally impaired. Some may have actual organ or brain damage. Other people have spinal issues, etc. Mindfulness approaches may help with quality of life – a worthy goal for sure – but it’s hard to believe they’re the way out for many.

One of Lenny Jason’s studies suggested that while coping (remaining within one’s energy envelope) did help many, it didn’t make a difference for a subset of patients. They were just too ill to benefit from it.

No Recovery Story Can Speak for Everyone

The many different ME/CFS recovery stories makes drawing any conclusions difficult.

One person got the question right, I thought, when he asked:

“He says that he recovered by listening to people who have recovered from ME/CFS and not to those who are still unwell. But which patients should we listen to? There are individual recovery stories after treatment with Rituximab, laser light, and neck surgery. Should we listen to them?”

Perhaps the most critical fact about any recovery story is that it’s just one of many. Health Rising has 63 recovery stories on its website that run the gamut from antiviral, functional medicine, diet, fecal transplant, hormones, mold avoidance, surgical and yes, mind/body (13 of them). I have 10-15 more recovery stories waiting to be processed which include recoveries due to functional medicine, DNRS, blood volume enhancement, fasting, yoga, ketogenic-meditation-functional medicine, exercise-diet-pacing-mind/body, etc.

Rituximab provides a good example of the complexity facing anyone who believes they have the answer to this disease. Rituximab did trigger recoveries in several people and did well in several small trials, but then failed miserably when fully put to the test.

The many ways people recover – when they recover from ME/CFS – boggles the mind. At this point, all recovery stories can do is point to possible avenues for people to explore.

Garner’s Unfortunate Ending

“I did this by listening to people that have recovered from CFS/ME, not people that are still unwell.”

Garner’s logic is impeccable – of course if you want to recover from something, you focus on people who have recovered. If he had stopped there, things would have been fine but the “not people that are still unwell” comes, whether he meant it or not, as a dig.

I don’t think Garner was being irresponsible in publishing his story. I believe that Garner’s public stance regarding his illness made it necessary for him to be public when he recovered. It was unfortunate and surprising that as a co-creator of the Cochrane Reports – the gold standard of objectivity regarding treatment success – that he didn’t put his success in context. On the other hand, for me at least, Garner’s suggestion to “spend time seeking joy, happiness, humour, laughter” is well taken. Particularly if you’ve been ill long enough, these things don’t come naturally – they need to be sought out – and can lead to an improved quality of life.

Conclusion

One purpose of this blog was to see if a biological explanation could explain Garner’s recovery. I believe one can, at least, be advanced. Another purpose was to assess Garner’s recovery in the context of other recoveries and in the context of what we know about the kind of approaches he took.

That attempt – aided by the responses to his blog – suggests that Garner’s recovery story is one of so many different recovery stories as to make it impossible to draw any conclusions about them, other than to note that some things work for some people and not for others. Garner’s recovery story is also clouded by the fact that it occurred early in an illness which had a relatively simple and mild presentation. As such, it simply presents a possible approach for those who are inclined to try that route.

Garner’s story and the controversy it has caused simply highlights what a black box both long COVID and ME/CFS are. With no diagnostic tests to tell us if Garner had ME/CFS, or a form of it, or something else leaves us stumbling around trying to figure out what his story means. The big takeaway is that ME/CFS remains a mystery – a mystery that can only be explained by science – and that’s what we need.

I meditated for an hour a day for two years and read and performed mindfulness the whole time. I didn’t know I had CFS, just that I was sick and not improving. The meditation and mindfulness certainly helped a great deal with the stress of trying to support a family as my health declined. However, it did not increase my energy nor limit my other symptoms by one iota. I’ve always been intrigued by spontaneous healing. Unfortunately, it does not appear to be something that can be reproduced. It can’t hurt, but the evidence is clear that it nearly always does not help.

It would be so nice if it was that easy. For a few people it may be and it certainly doesn’t hurt to try. For me I would be looking into that kind of stuff if I was healthy as well.

I really appreciate your well thought out, balanced approach Cort. Actively seeking positivity in our lives definitely improves quality of life. In some cases, it may even elicit a healing response. So we should all go for it; it’s not expensive, will not take us out of our energy envelope, and will keep us hopeful as we wait for science to help us out.

Great piece. One thing I keep wondering is why did Garner claim himself recovered before let’s say a 3 month (relapse free) mark? Why not wait a while? I’m secretly wondering whether he really did get better or just had a good phase,

Hi Cort,

much has obviously already been said about Garner’s exercise-your-way-out-of-it approach, so I’ll comment on a point that might have seen less criticism. You mention that his logic is impeccable in taking advice from those who have recovered from me/cfs. I think this is fallacious. Presumably Ganer refers to narratives of recovery from individuals, i.e., anecdotal accounts with stat sample sizes of n=1. As you clarify in your response to Garner here, anecdote does not constitute conclusive or reliable research. It is like asking centenarians the cause of their longevity. I for one am exhausted by chronic illness history as told by those who are not chronically ill: a victor’s history that ignores the casualties. The last thing me/cfs sufferers need is anecdotal advice from self-congratulating members of a mutual admiration society. When a cure or successful ameliorative treatment for this disease does eventuate, it will be the result of sustained, funded scientific research, not the piecemeal collation of individual stories of happenstance and wishful thinking.

Paul Garner emailed me back in early October after I sent him information on Orthostatic Intolerance. (This is around the time he now claims to have fit the Canadian Consensus Criteria for ME/CFS).

>>>Paul Garner 10/5/20 PG To: Brendan …> Yes, thanks! I don’t have these problems at the moment. I am trying to find in the literature how to sensibly reintroduce exercise. I do 5 km walk a day, do I just keep increasing this, or do little runs between the lamp posts and see what that does? Whilst I see that people say don’t push through the fatigue, I am not really in that position, just looking for a way when I feel fine to do more in a careful way. Is this in the ME literature?

Best wishes Paul <<<<

Proving he could push through fatigue back then, (the PEM he had appears to have gone). He was already increasing exercise little by little and by mid October he emailed me "Biking now"

I even emailed to him I didn't think he would develop ME/CFS as he was recovering. and was able to exercise.

Reading his blog, It seems his 'mind therapy' started 7 months after his 'mid March' Covid infection. Meaning he was already on a good path to recovery.

I personally don't believe he ever fit the Canadian Consensus Criteria for ME/CFS

because he was constantly improving (except from the odd crash) prior to his ME/CFS assumption during this period.

What's upsetting is the help he got from us (he did a call out on twitter), most probably helped him not worsen, by avoiding pushing through early on. He didn't have that problem later. Yet that was all prior to his mind therapy.

I'm not happy with his 'dig' at us who remain unwell.

A scientist who chucked science out the window. He's a disgrace,

Anyone wanting to share the screenshot of my email from Paul feel free to contact me at

vespa.bw@gmail.com

Well that’s pretty telling. He was clearly starting to improve….Very interesting – thanks for providing that.

It’s unfortunate he didn’t provide that in his blog. It seemed like he was at a stasis point and then started this new approach and boom..

He was healthier than it seemed.

He went diving to Grenada ( whilst in lockdown) in November (?) and caught Dengue.

Latest blog uses completely different language and tone.

A lot of conflicting and conflating info .

5kms is a lot, my son can’t do 500 metres and hasn’t since he got sick a year ago, with EBV mind you. It’s clear he didn’t have ME/CFS and it seems the help he received from the ME/CFS community assisted him to NOT go on to develop the syndrome. Lucky him

Well I think you are just rude. I have had ME/CFS for as long as I can remember and the illness has fluctuated over the course of my life with a particularly bad episode around 2017. I got COVID in Nov and have since become a lot worse with ME/CFS, POTS and OI. I walk an awful lot every day, easy over 5K I average 9000 steps per day. Yes I have PEM, yes I feel rubbish but I don’t “only have post viral fatigue” I am sure that I am lucky to not be considered severe, but I still manage to walk, I do this to avoid clogged arteries and deconditioning for as long as I can.

Hi,

When I read: “>>>Paul Garner 10/5/20 PG To: Brendan …> […] I do 5 km walk a day […] Best wishes Paul <<<<" my jaw just dropped.

Who on Earth can believe they have ME/CFS when they can walk 5km a day, that is, everyday? Honestly? Who is the idiot who made that diagnosis?

Paul Garner is one of these people who is given credit because he is a man with professional titles and who will bring all ME sufferers back to square one.

I've had ME/CFS for 34 years and was diagnosed with early stage of heart failure at 45 despite a BMI that never went above 18. I'm now 49 and I'm running out of time. I'm sick and tired of the kind of crap he conveys.

Yes that’s how I interpreted it, that Paul Garner was walking every day and I presume for about a month prior to October.

He did in an email at some stage saying “taking a break’. As I told him not to exercise daily if he wanted to avoid constantly reminding the immune system to attack causing PEM (which he did have in the earlier months). I think he was back then taking our advice not to exercise.

I was pretty sure he had just Post Viral Syndrome as I followed his tweets and interviews and the main thing was he was seeming to be improving little by little. In an email I even said that I didn’t think he had ME/CFS.

No educated doctor on the subject would diagnose ME/CFS if they knew someone was improving, because thats a big indication the person may only have Post Viral Syndrome that normally eventually it resolves itself (can take some people up to 2 years, but they improve like the property market, ups and downs but over all heading upwards)

Anyway by mid October he emailed back “Biking now”.

So I was upset with his BMJ article because he said he received unsolicited emails for the ME/CFS community. Thats not true because I have a screenshot of a tweet he made asking for advice.

I still think Paul is a decent person though, I just think he made a huge mistake in the way he wrote that article, and probably doesn’t realise the damage he’s done. Maybe he was upset he was told not to do any exercise when the reality was it eventually wasn’t a problem for him.

I have a feeling someone from the fraudulent Lighting Process or Graded Exercise proponents have got to him knowing that most people with fatigue after a virus improve anyway.

To him as an individual it would have come at just the right time, so would have seemed to be the answer. Unfortunately for those with ME/CFS that mind therapy and GET nonsense doesn’t work.

Hopefully in the future we will eventually see an apology from Garner.

He was out running and exercising all the time, several times a week in summer, he is well known in his local area

For an educated medical professional to make the comments he did, having every reason to understand the negative potential on a beleaguered population, was extraordinary irresponsible. To preach from his professional mountain top about something he has no proof of and cannot be objective about is maliciously arrogant, showed a complete lack of scientific thinking, and a complete lack of empathy.

Perhaps he has lingering brain damage?

“Perhaps he has lingering brain damage?”

I guess he is rightfully euphoric to be relieved from such utterly crippling symptoms similar to those we suffer day to day.

With his carreer being a path of fighting infectious diseasse and fighting for more and better science based medicine it indicates that this euphory is so overwhelming that he ditched much of the values he fought for during his entire previous career.

While his blog bulges from the un-science, it indicates that recovering from what he had is an utterly overwhelming positive and life changing experience by itself. How else then lifechanging to call an experience that makes one throw much of the professional credibility he build during decades under the bus?

If having again the ability to function and work normally likely is such overwhelming and life changing experience, then maybe his void-of-science-blog is a testiment to how bad his previous ill state was?

If anything, such potential euphory by itself holds the risk of losing and releasing all leashes on rational activity and rest management that any person healthy or ill should have. To me it seems as if he is creating the foundation for a much more easy to trigger future relapse.

I think he had to…..He was very public about his illness- so how could he not be public about how he got better? How could anyone really after getting so slammed by this illness?

I think Paul could have worded his story better. I’m a bit surprised that, given his background, he didn’t make it clear that his was an N of 1 (or 2 or whatever) and this approach might not apply to others. That would have been helpful

Dejurgen may have the best take on this – he’s kind of euphoric! No surprise there.

Reading this makes me wonder what could happen if we had a biomarker available to identify ME early and try treatment. I’ve tried everything he did and did improve my condition, but there’s no way I could take up running like I did before onset. It took me almost 3 years to get diagnosed, so I can’t help but wonder if I’d known right away and tried all the things right away, if I would have recovered like he did. We really can’t compare the outcomes considering the difference in diagnosis paths. It’s just more support for the necessity of early diagnosis and treatment.

I was thinking the same thing. What if I had known to rest? To pace? Or had made a conscious effort to do what Paul did early on? I tend to think it might not have helped. I was worse off than Paul – but who knows – the EST training I did within a year or so of becoming ill – was kind of what Paul did on steroids and it did really help. I certainly did not get well – nowhere near it – but it helped tremendously.

Strange for him to draw conclusions from an “n” of 1. I thought he was a scientist? I’m with those who believe something about this experience is clouding his thinking.

Most of all: Thank you so much, Cort, for today’s excellent, very insightful piece about this news. It’s great to be aware of news, multiple perspectives and discussions about ME. Again, as always, great job and I’m really grateful.

To be honest and fair I don’t know if he does draw conclusions. James points out that he says “My experience may not be the same as others”. It seemed to me that he was simply speaking about his experience.

This is a great article but I think Cort lets him off a little easy given his influence. If he were just another patient recovery story that would be one thing but his words have the power to significantly influence policy and practice. Personally I think we always have to assume coincidence since humans natural tendency is to tell a story that, while satisfying, is not always particularly objective or even accurate if all the facts are considered. This is the cornerstone of the scientific method which Garner pretty much ignores in his piece, instead opting to tell a satisfying recovery story. Below are the comments which I left on the BMJ post and I think are still relevant after reading Cort’s article.

***

As they say correlation does not equal causation. Just because he stopped focusing on his symptoms at the same time as his symptoms improved does not mean one caused the other only that they happened at the same time. I would argue that it’s just as likely that the weeks he spent “[learning] that I could change the symptoms I was experiencing with my brain, by retraining the bodily reactions with my conscious thoughts, feelings, and behavior” were the final weeks of his recovery from having had the virus so of course it coincided with feeling that he “… would recover completely” and his seemingly miraculous ability to exercise. The problem with this article is that it does not point out that unfortunately this will not be everyone’s story, no matter what therapies they try including the one suggested here by Professor Garner. He does say “My experience may not be the same as others” but I think this is an understatement. “My experience will not be the same as some others” would be more accurate.

In regards to his statement “I believe that we can unwittingly reinforce, as Pavlov has shown, the dysfunctional autonomic tracks in the brain set up by a virus long gone.” I’m sure we can, and indeed exposure therapy can work well when this is the problem (whether the phobia is spiders or your illness symptoms) but if it works then you do not have, and probably never had, ME/CFS. Because in ME/CFS the exact opposite happens. Ignoring symptoms and pushing the envelope makes one’s symptoms worse, sometimes dramatically worse. Every. Single. Time. Until you learn what your body can and cannot tolerate.

I think if Professor Garner wants to talk psychology he needs to take a hard look at whether he truly believes the therapy he undertook cured him or if he simply doesn’t want to face the fear that he too could have ended up an ME/CFS patient (but thankfully didn’t). Humans have a strong need to have control over the world, particularly illness, and tell stories where they are successful, even if those stories are not backed by scientific evidence. This story of his reads like someone who wants to feel like they have some control over a very scary illness, that he DID something and was able to make it go away. Maybe he did, and we can all hope future research will figure out ahead of time which patients would benefit the way he did, but we are not there yet. And so ME/CFS patients will continue to advocate for pacing, paying attention to symptoms and learning what leads to improvement for each individual, rather than assuming that we know what is the root cause of each person’s suffering.

“There are individual recovery stories after treatment with Rituximab, laser light, and neck surgery.” I’m familiar with Rituximab and neck surgery, but how does laser light help?

Does anybody here know any CFS patient who recovered after treatment with laser light?

I don’t know of anyone who recovered using laser light therapy but Doidge does cover it in his latest book I believe. I wouldn’t be surprised if there was some application.

Living in England it is hard to access Fred Kahn’s cold laser treatments (as mentioned in Norman Doidge’s ‘The Brains Way of Healing’). I have a 6 year label of fibromyalgia and 5 years ago I went privately to Dr Peter Herbert in London for 8 treatments with Fred’s complex professionally administered equipment. Dr Herbert had gone to great lengths to import and was treating people for all kinds of problems. I would go white-faced to the treatment and come out with rosy cheeks (better blood flow to brain?) tingling and calmer. Then I had a friend in British Columbia send over the Bioflex Personal Therapy (patient treatment) not available in Europe. I use it every day. It hasn’t cured me but it has helped with my structural problems. My aim is to avoid surgery and so I have been seeing a TMJ dentist in London every 3/4 weeks over last 3 years for customised treatment – adjustments to appliances every visit. Not a cure as my energy production is still bad but a help – no longer brain fogged am happy

Let’s hope that Paul Garner is well and stays well, and that his apparent brainfog clears up. Meanwhile, his story is anecdotal and _even if_ this story were a solid study, n would = 1. That is, if we had data and test results of Garner’s case such as brainscans, blood analysis, and more.

I’ve collected a two-page+ list of links to studies and papers that show numerous objective, measurable traits found in the brains, blood, and bodies of people experiencing _documented_ cases of ME/CFS. Many of us have stashes of information like this, or better, of course.

It looks like Garner’s writing as to his own experience was written by or copied from Live Landmark’s questionable Lightning Process — PR/marketing items.

Has Paul Garner personally shown any of the ME markers such those previously documented by numerous solid researchers? …Such as plasma proteomic profiling (Nancy Klimas and researchers at numerous universities), or inflammation of microglia (Karolinska Institute, MGH’s Marco Loggia, and more), a 2-day CPET, or anything – markers – to document what his post-Covid condition really has been over the past several months? …Or any solid information? I doubt it, but I wish us all a rewarding recovery from ME, so please bring on the objective evidence.

Excellent point Elizabeth – which really points to a vital need – to get a set of tests down which can serve as diagnostic biomarkers. I wonder what a nanoneedle test would have shown? I get that Paul was really sick. I think he had something akin to ME/CFS. Whether he had all of it or part of it is unfortunately a question we can’t answer. How much further ahead we would be if we could….

Elizabeth, Paul told me he didn’t have Orthostatic Intolerance, nor problems pushing through at around 6 to 7 months after infection, as he was walking 5km a day. He did have PEM earlier on though. So I’m thinking he only had Post Viral Fatigue Syndrome

Let’s be grateful he could have written a book.

How I went from sickness to health and you can too.

Only $26.99

Another to add to the library

Then again Doctors tell of patients believed soon to pass only a day later to fully recover.

RonP, you are right! Then, with the book promo tour comes the – heaven help us – the media blitz. Shaking my head.

his words from news video link in this article:

“to ALLOW the body to recover” (from video in article)

I put emphasis on the word ‘allow’

how many have been ill 20 years and are still ‘ALLOWING’ their bodies to heal—to no avail.

if he is the poster person for typical long covid i am surprised if any are being given an ME/CFS diagnosis.

if instead he were ill for a much longer time, would he have switched and ‘tried to do what those who had been sick a long time did to become well?’ …………………oh,………… wait………………………………………………

……………those who are sick a long time ………….generally………………………………….DON’T …………

…….’become well’……………..

Maybe what we should be supporting is a trained camera crew who can video each person with CFS/ME and that is the ‘test’ needed for others including doctors and insurance companies to ‘see’ how ill people are.

i feel like making this person’s ‘long covid’ akin to the suffering of most cfs/me person’s is like comparing someone with a bout of flu to …….i have no words 🙁

Glad he recovered, and hope many more do recover fully.

I hope that those who do not recover have friends and family that can document—-as hard as this sounds—-thru video —their stories.

And help them get help.

somehow word got deleted—

wish i could edit it——should say:

………….generally…………DON’T……………become well……….

Great point! Allowing just does not do the job does it? It helps….but does not do the job. Nor does “turning to the light” so to speak for most of us.

@Cort—

an excellent analogy made by person named Sten Helmfrid

comparing if cancer patient were told that being positive caused recovery—

https://mobile.twitter.com/StenHelmfrid/status/1358361042225684482

Sten Helmfrid makes a very good point. I’ve come across this ‘think positive’ for decades and I think it can be a very narrow view. At the more extreme end I think it can be a bit like a cult – you have to believe or you’re out.

I tried it myself with food – thinking very positively that I was absolutely fine, I ate some gluten free bread (loaded with maize, so very high fructose) – toasted – and was stricken down, like a cartoon character.

In reality I think it depends what’s gone wrong with someone. If your sympathetic nervous system has been chronically triggered and that is quickly rebalanced, then great. But if there’s a range of issues, like inflammation in the brain or elsewhere, immune issues etc like I believe I have, then the situation is much, much more complicated. Especially, I think, if people are misdiagnosed and treated incorrectly.

I can be viciously negative, which doesn’t actually help but neither does being blindly positive. It doesn’t take a genius to realise that it’s vital to carefully and methodically establish what’s gone wrong, before a valid treatment can be found.

I prefer to feel optimistic but I’m a realist too. Denying someone else’s experience, whatever that may be, can be very destructive, whereas acknowledging their experience (even if it can’t be changed) can be validating and that, I feel, is important.

Hi Cort

Thankyou for such a balanced and delicate walk along this contentious line.

Personally, I am still trying with brain training. When I do this 24/7, I see little improvements over the course of weeks, and I feel much better in myself. However it is sooo much work and so hard when your brain is racing downhill in the opposite direction, and I’ve not managed to pursue this consistently enough to make proper consistent and reliable progress. But I feel it is possible. At least in theory, depending on the extent of “brain injury”.

I read in one of your articles last year you were in a similar on/off mode with DNRS, how did that journey continue for you??

All the best to all the people here. Steve

My experience is similar to yours Steve. Enough movement to keep me going but not nearly enough to get me there; i.e. no big breakthroughs. I had some movement with the DNRS, stopped doing it, but plan to take it up again.

Cort said – “For years I’ve asked myself: where this fear and subclinical anxiety comes from? Why is it so difficult to settle down? Why do little things bother me so much and why do they affect me physically? My guess is that this is, at least for me, part and parcel of a disease process that affects the two major stress response axes (ANS, HPA axis) and the immune system.”

It was amazing to read this Cort because its EXACTLY what I experience especially when something comes along to upset my day to day equilibrium, be it a nasty virus, infection or any other significant event. This is very fresh in my mind at the moment because I have been suffering so badly in this way after a very bad response to Botox for Chronic Migraine which affected me more or less immediately after it was done.

It has affected my CNS so badly and also my autonomic function with symptoms like dizziness, orthostatic intolerance, worse migraines and very poor energy. I ended up with a throat infection because it was so stressful to my body and throughout the whole horrible period my sleep was horrendous with accompanying anxiety which I don’t usually suffer with so when I read what you wrote it was as if I had written it because it was my experience too.

I haven’t read the rest of your article yet but felt I must just comment and it does help me to know I am not the only one who suffers so badly when something comes along out of the ordinary and for which a “normal” person would hardly be affected. I cannot believe it’s just a case of aberrant thinking because it doesn’t explain how the rest of the time I can function relatively well, be it at a very limited level.

Thank you Cort for all your brilliant write-ups.

Pam

Hi Bertiedog/Pam,

I would experience the same sort of difficulty regulating my emotions too. This would have started after I was unwell, with a very nasty virus 4 years ago. Before that, I could be depressed or anxious but not with the level of volatility that I can experience now. Generally I’m okay and if I’m not, I know that it will pass, I just have to hang on. If I’m completely worn out, I think I resemble a small child that is overtired and is about to have a meltdown.

I think I’ve just adapted to having to manage this. I’m fine if I’m working with my homecare clients – then I have a particular role and I’m able to deal with some very tense and stressful situations. But if someone changes something unexpectedly for myself, I get stressed and a bit confused.

Hi Cort, Thanks so much for all your great explanations!

Just to be sure, I hope you didn’t forget the promised Part 2 of Mitochondrial Enhancers?

Take your time en keep safe,

Désirée

It’s coming! 🙂

It is well known that patients can recover within 1 or 2 years after an infection (such as Epstein- Barr virus) or severe stress. You don’t have to meditate or walk 5 miles a day for that. He just recovered. I am happy for him and all those others who have been healed. I believe that the ANS and stress respons in ME/POTS patiënts are broken due to ……. ? If you now the answer, you win the nobel price.

I also had email correspondence with Prof Garner in May 2020. He was completely under the weather at that point (relatively speaking) and still bothered to get back to me. He seems a nice bloke, and not arrogant.

So his anti-vaxxer-worthy-drivel on that opinion piece is a real surprise. Give his intellect, experience and the little I can glean of his apparent good character, I think something is seriously amiss here. This just seems like the calm before the storm for him. Some sort of desperate attempt at justifying something. It is like someone who has spent way too much money on the crystals that are recharging in the garden but can’t deal with the prospect of admitting their head was up their proverbial. If that sounds like unfounded psychobabble, it is, but so is his whole article so no advantage, play on.

If he crashes, please don’t crucify the guy. Crucify his opinion piece by all means – it is complete rubbish and very dangerous and that needs to be addressed. However, we’ve all had irrational moments of wanting to believe we were getting better early on with ME, with some weird theory to back up that belief in our heads. It would appear that not even infectious disease professors are immune to utterly irrational BS when reconciling with their own severe illness. ME patients don’t use their position of authoirty to wholesale undermine a set of disease sufferers, but most of us didn’t/couldn’t raise the profile of the disease in the first place either.

That type of mind-blowingly unscientific anecdotal clap trap requires some loose wiring and is exactly the type of thing doctors are trained to look out for and take with a grain of salt. So I suspect it won’t just be the ME patient community realising this bloke has lost it and might need some help. Perhaps he isn’t back at full mental capacity and doesn’t realise it.

Key things to remember when thinking about his claim:

1) His story is simply his story. CFS has multiple causes. If he’s so confident his approach is the solution, then he should do a large-scale clinical trial with people still affected after many years. A scientist should know that anecdotals are simply anecdotal. Hopefully he is thinking this through from people’s comments.

2) “Those who are blessed with good health are sometimes cursed with a lack of compassion.” People who’ve had success, for whatever reason, are sometimes quick to blame a person’s thoughts or attitudes for their problems. That’s just human behavior. He wants to cry, “Eureka! I’ve found it!” so maybe he will embark on a scientific study and create a helpful program. There are gurus all over, and psychology fads have come and gone. Like medical practices, one size doesn’t fit all. Maybe he will add to the pot of things that have worked for some people, and that will give us one more thing to try.

3) As Cort said in so many words, the brain is a physical organ, influenced by thoughts for survival reasons. We can’t ignore that. It’s very helpful for long-term CFS patients to go directly to Paul’s blog to comment, to ask him to take a scientific approach to test the validity of his theory.

4) When people pull through a lengthy illness, there can be a feeling of success. That emotion can last weeks, months or years. But what happens when he suffers an emotional loss? How much could he control the physical sympathetic, say, the death of a loved one? Since people with CFS and other autoimmune physiological illnesses have sensitive immune systems, it’s very possible that his “Eureka!” will lead him to a new understanding.

Oops…. in #4 “sympathetic “ should have been “symptoms”

I hope this blog and comments can be sent to him and he reads it.

I’ve had ME/CFS for 20 years, been disabled by it and improved significantly but am still not fully recovered. I’ve used tools such as yoga, tai chi, meditation and especially mindfulness and they have helped calm my system down as well as the anxiety / depression, but they have not been a cure for me either. I’m also only using mindfulness these days.

Like you, Cort, I still have a system that is highly sensitive and reactive although this has all been improving (if slowly!!).

Given that these mind/body approaches work for some people I suspect that those of us who are not better have bodies caught in a deeper state, perhaps as a result of a larger number or bigger “multiple hits” (early traumas including prenatal stress, birth events, childhood events; and /or maybe more exposures to other forms of threat such as infections although sounds like he’s had quite a few infections, etc).

Ultimately, I wonder if those of us who are still sick have a stronger, more entrenched type of cell danger response pathway. As such, supporting the Smart Vagus / PFC / social nervous system is not enough to resolve my own highly activated states of fight/flight and freeze, and I actually need to more directly weaken those pathways from the other branches of fight/flight/sympathetic and especially the parasympathetic dorsal vagus branch that controls states of freeze (for me it’s been through trauma therapies, which have been found to be able to chip away at freeze and reverse epigenetic changes, just as other tools for folks with ME/CFS may be doing). I suspect this is what makes some of our bodies still so super sensitive to so much because these bodies of ours are still scanning for safety. From that view, maybe his understanding of covid as an infectious disease specialist helped him not go as far down the rabbit hole of fear as some of us might.

This is such a contentious issue – I’ve deleted about 4 comments already! So, what I’m going to say is… that firstly I think we’re all so different in our backgrounds, genetics, environments, levels of support and understanding from others and so on. For me, not understanding what was going on with my, ever changing, serious health issues – with no support, was devastating.

What made the biggest difference for me was understanding and becoming aware that my sympathetic nervous system was stuck on high alert 24/7 and that was completely unsustainable. I knew I was wired – that was obvious – but I thought it was better than the shut down I’d previously been in – at least I could get through the day. But I ran out of energy and I was intolerant to nearly all food and my system couldn’t keep up – living in an energy deficit situation is truly terrifying – and who is going to understand that?

Now, I have a training in counselling and psychotherapy and I knew that what was going on for me, was way beyond the regular realms of therapy. However, my experience within that world gave me a framework and a confidence to focus on calming my stress response and improving my sleep (and lets face it I just had to, otherwise I was not going to survive and I had a teenage son that needed his mother). These two changes then laid a foundation for slow but continued improvement over the last two years.

Currently, I am working on salvaging what I can from the wreckage of my life – work, family relationships, friendships, financial situation and so on and integrating my experiences of being so unwell and so dismissed, into some sort of coherent, identifiable narrative of my life and not something I feel ashamed of and need to hide. I haven’t succeeded yet – I just see it as the next step for me.

So, in relation to the blog, I’d say that’s good for Paul Garner that he’s feeling much better but maybe he could show a bit of compassion for people who are still unwell (and maybe helped and supported him?) and who are not as fortunate and well resourced as he appears to be?

Thank you so much for publishing this. I’ve learned a lot!

As a Covid long hauler who kept detailed daily journals of symptoms, activity, food, medications, etc. it was very clear to me in the first few months that excessive activity caused more symptoms.

But somewhere along the line,

that changed — and now physical activity makes me feel better, with no crash.

I wonder if that’s what happened to Mr. Gerner.

Congratulations Mike. It sounds like your body is healing. Keep it slow and steady and hopefully everything will resolve.

Ack! A subject that never seems to leave the ME/CFS community “alone”, no matter how much time, research, and suffering goes by…

Here is the way my own layman’s brain makes sense of this tightrope of a subject:

First off, every time this issue resurfaces a whole bunch of expletives first come immediately to mind. Then (calmer) I think…

Surely MANY things will eventually prove to be able to leave a nervous system perpetually “on edge”. Recovery stories like this man’s (appear to) show that some type of “re-wiring” or “physiological PTSD” (however it is best understood and described) from past insult can be one such thing. But, if that is indeed true, then certainly ONGOING exposure to chronic insult has an even GREATER ability to leave people sick, disabled, and their CDR and ANS in “stress response” mode…because what greater stress (and legitimate threat) is there for a body, really, than illness itself: chronic inflammation, chronic infection, autoimmunity, spinal damage, etc.? Those people will not be helped by addressing only the neuroplastic “echo” of the disease, but will need to be treated for the very real and persistent stressors that remain on/in their system. (And they may then, or concurrently, need some type of neuroplastic re-training, or re-wiring…or, not. Their systems may calm down automatically as the stressors are removed. That latter scenario is how it has worked for me, personally.)

People with very mild cases of physiological stress (such as some sources of chronic inflammation, for instance) that are contributing to keeping their systems on high alert, may be able to break the cycle using mostly, or only, mind-body techniques. (As the mind calms, the body then calms and re-regulates it’s broader function.) But I highly suspect this only represents a part (and perhaps only a very small part, at that) of the total ME/CFS population.

The symptoms of the two populations could look similar enough that much commentary on such an overtly-ignored field of study would miss the differences. Both sets of bodies are in a chronic “stress” state. But the needed solutions are very different.

We need complex thinkers in this field: those that can take in multiple overlapping and inter-related realities and states of physiology and psychology and neurology, without mistaking one for all the others. That is why every time I watch the subject get re-whittled down to some overly-simplified explanation for all cases, it is so terribly sad and frustrating. And is a real threat to progress, because as a species we appear to love simplicity, especially when it is used to explain things that frighten us, to explain away and diminish other people’s suffering, and those that threaten our own sense of control.

Thank you, Cort, for taking on another sticky subject. Your work is so needed and so appreciated!

When I got sick, I pushed. When I got sicker, I pushed harder. When they told me to exercise, I went out and got a gym membership, and pushed and pushed. I never got to gthe point of not trying to ignore my pain and illness until it completely overwhelmed me. If anything I took from his story, it was his ability to rest in the beginning. If he in fact ever had mecfs, that to me is another question. Good for him. But i,n not sure his story is our illness. I was not diagnosed for over r years.

I think there’s something to be said for his experience for sure! The only thing I questions is that he did military style fitness and was fine after. Even for someone using brain retraining techniques, I don’t think they’d be fine after military style fitness….at least not in the beginning of the illness.

I am getting tired of this merrygoroud about psychological problems causing long Covid and M/E CFS, a number of doctors want to take the easy way out. And now we have to put up with Paul Garner joining them. ME/CFS and long Covid are the same both are viral infections and in some people the immune system struggles to clear the infection completely. It all comes down to a person’s immune system as to how quickly the virus is defeated. Some people inherit a stronger immune system and defeat the virus quickly while others take longer and during this time should take things easy so the immune system is not under any stress which may be resuming normal activities like work etc. If a person has a stressful job or maybe relationship stress or everyday stress the battle to overcome the virus may be prolonged and the immune system continually becomes weaker and the virus gets stronger moving to various parts of the body creating more stress and the body becoming more fatigued. Also if a person was given as I was for viral sub acute thyroiditis, any corticosteroids (prednisone) the immune system is greatly weakened and the virus gets stronger. Doctors are reluctant to talk about the dangers of taking prednisone on the immune system especially when the person has an active virus. Nancy Klimas has got ME/CFS correct with it being neuroinflammatory and inflammation in the body affecting all the body, and found when looking at people with ME/CFS their N Killer cells were not attacking infected cells. She didn’t think there was anything wrong with them and hypothesized that they were worn out . Paul Garner just needed time as so many other recovered people do. Except for some whose immune system is either heritary not as strong or under stress weaker or given steroids and have unresolved viral infection ME/CFS. I sincerely hope nobody takes notice of his psychological rubbish. I have been PCR DNA test diagnosed Chronic Active EBV. EBV serology is not sensitive enough or reliable for EBV test. Nancy Klimas is on the right track.

Hi Dennis, have you come across Amy Proal PhD? I think she’s very interesting in relation to viruses and other infections. Dr Proal did a webinar for Solve ME/CFS Initiative, probably Sept 2019. Hopefully it’s still available. I think she’s teamed up with Michael Van Elzakker, which would be a formidable team.

It’s still there but it’s Nov 2019 – Amy Proal PhD is a microbiologist. I thought the webinar was fascinating.

Thanks Tracey Anne

Just finished watching Dr Amy Proal’s presentation Nov 2019 although very complex a lot rang true for me . I had seven viral episodes the first in 2002 after ongoing stress which must have weakened my immune system. Within six months was diagnosed viral sub acute thyroiditis, symptoms like glandular fever. Prescribed Prednisone 10mg 3x daily. Felt good on medications but once ceasing was having trouble breathing. Was then prescribed Symbicort another corticosteroid medication weakening my immune system, within one month of commencing symbicort I once again came down with the same virus in 2004. I was obviously having trouble with my immune system taking Symbicort twice daily and and any increase in stress the virus kept coming back another five times and each time I was becoming weaker. Pushing myself all the time never allowed my body (immune system) time to recover and getting weaker each time pushing myself became more stressful and still taking Symbicort kept my immune system weakened. After last viral attack 2014 thought I might have CFS, but doctors didn’t want to know,(no such thing.) Never knew what was happening to me. Only in the last three years with research do I now understand how I progressed to mostly housebound ME/CFS. Dr Amy Proal’s presentation mentions stress affect on immune system and immune suppression medications yet as Dr John Chia said doctors hand out Prednisone as though it’s holy water. Big Phama making to much and not caring about the consequences of interfering with people’s immune system as some with ME/CFS are a result of Prednisone or corticosteroids.

Yes, it is complex but Amy Proal’s ideas made sense to me too. After I had glandular fever/mono when I was 17 (though I did rest at the time) and recovered from the illness as such, throughout my 20’s and early 30’s, if I became tired, run down, stressed etc I would become unwell again – my glands would swell up, I’d have a sore throat and I’d be very tired. If I listened to my body and slowed down, the symptoms would lessen and go. If I didn’t slow down and rest I’d become sicker.

Now, I don’t have those symptoms (I can have a load of others) and I’m doing fairly well. I think that at the moment I’m managing myself as well as I can, to function as well as possible, in a reasonably flexible/attempting to be relaxed (!) fashion… sort of like coaxing a temperamental vintage car.

Also, when you posted originally, I did read them, I just go through times where I get very tired – my brain is most affected. Anyway at that time, in relation to you, I looked up patient safety and the World Health Organisation popped up. (I just found the piece of paper I wrote it on!) They, it would seem, are very well aware of the issue of harm caused by health care workers. Medication Without Harm is one of their campaigns.

I currently work part time (I couldn’t work full time) with people in the community as a home caregiver. Apparently there is an issue with older people being on too many medications, some which may be contra-indicated to be taken together.

Reminds me of a certain American president who got away with COVID 19 …

like you said cort, in the dubbo study, many recovered to over time but a % stayed ill. I do not know how ill. and how many me/ cfs types are there? subgroups, we need and researchers know precicion medicine. And the co-morbiditys over time.

And the strongest of all, i know someone who worked in breastcancer research and he said, take 1000 patients and there are allways a few spontanious healings! that has he not done 🙂 or 🙁

maybe he gets a relapse over time…always possible, the boddy is so complex!!! but what he says is nonsense, ofcource there are many long covid patients who are going to get better (scientist never said otherwise, only x % would really develop me/CFS) or develop something else or never get me/cfs

but when he can heal himself with positive thoughts from a serious cancer, parkinson, dementia or so, i say waw!!!

Hi Konijn ? I often think of you and wonder how you are…

Ahhh, so many emotions flood my brain as I have read both the blog and comments. In the Buddhist way of thinking, one thing is for certain in life, and that is ‘suffering’. And people get tangled in the ‘whys.’

I’m someone who is balanced between the scientific and the spiritual and have a special interest in spontaneous healing. I’ve had a Near Death Experience and so attended IANDS meetings for years and have listened to numerous accounts of unexplained healings and other spooky events.

I’m dissatisfied with doctor’s visits yet still I make appointments. I read every research paper or story that comes out, because I will always have ‘hope.’

I have seen the power of the mind yet know it does not always control the power of experience. Everyone seems to be on their own trajectory and as most people do, I have formed my own ‘why’ about this–that anyone’s experience is meant for them alone and is their life’s lesson.

That certainly does not mean anyone should ‘give up.’ I know I won’t. Once I heard someone say, ‘perhaps you cannot be cured, but you can be healed.’

I suppose the best I can do is to wish everyone the most kind healing wishes and to relax into (to quote EST) ‘what is’ and continue the search but with the belief in divine intervention or scientific epiphany.

I posted this before. I had Long COVID for 5.5 months I got rid of it with 4 sessions of IV Ozone Called 10 PASS OZONE IV. I found it out thanks to a Right to Know Texas Case. I has been used in Italy as well.

A somewhat sad story but perhaps understandable. What we know of Mr Garder was that he had chronic Covid 19 syndrome (CCS). What we do not know if he had ME/CFS as part of his CCS. Work by the Scheibenbogen group (https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2021.02.06.21249256v1) shows that there are a few distinctive features that may set the two entities apart, including “more stress intolerance and more frequent and longer post exertional malaise, and hypersensitivity to noise, light and temperature.” So did Mr. Garder suffer from ME/CFS triggered by Covid 19? We don´t know.

But sadly, he generalizes from his own experience, in a condescending way (in my opinion) but – more deplorably -, in a non-scientific way. CCS is not yet well delinieated in terms of its prognosis and in its relation to ME/CFS, so how can he start to give general advice? What if his advice is only helpful for a few CCS patients but detrimental for others? He should know that currently there is too much uncertainty as to come up with far reaching medical advice from personal experience. I just hope he will at some point come up with clarifying thoughts.

For his vindication we also have to analyze the reaction to his case in the ME/CFS community which often included the statement “this is ME/CFS”. We have to be careful and stick with what we know about ME/CFS: it´s not just fatigue. And ist not just fatigue plus some weirdo symptoms. From what Mr Garder offers about his clinical course in his opinion piece in the BMJ I see a lot of weirdo things, some of which are also part of ME/CFS – but is this ME/CFS? “I had a foggy head, acutely painful calf, upset stomach, tinnitus, aching all over, breathlessness, dizziness, arthritis in my hands, weird sensation in my skin, extreme emotions, and utter exhaustion and body aches throughout. I had ringing in my ears, intermittent changes to my heartbeat, and dramatic mood swings.” He should be familiar enough with the literature as to be more weary to call this ME/CFS. I am glad for the work by Scheibenbogen et al who try to figure out how much ME/CFS there really is in this mixed bag of chronic post Covid-19.

Here is the thing with him, it is wonderful that he was able to recover as he has, but the fact remains that many have not, will not, and the many with ME/CFS worldwide do not want to feel the way they do. Does everyone with the illness always do exactly as advised, all natural, mind meditation, acupuncture ,constant follow up of blood draw, maybe not, and maybe because they also do not have the energy to even get there, possibly the funds that cannot cover extras.

The fact remains for many, no matter how many head doctors mentally one is sent to, diagnosed with depression or not, the symptoms they experience physically that can range in varying degrees, just like Lyme disease, ebv etc.the fact remains the patient feels the way they do and to sign them off to head shrinks as has been done for way too long, and without funding and research to assist all of these patients is way beyond at this point. Many years of loss of work around the world due to the ME/CFS problems. Who wants to experience any of it, no one. So just because one patient may fair well with other modalities, it does not always fit for another, one size does not fit for all.

Personally the way I explain the fatigue or at least at the worst times with ME/CFS, mast cell activation, and other stuff off an on, it is like you are carrying a guerilla on your back. Another analogy you may feel light weight in the pool, and can do various things in the pool but when gravity takes over and your last leg is on deck, the guerilla jumps right on your back again. Learning to meditate, doing acupuncture, supplementing with vitamins and other natural items are always good to try, and if the body reacts to this in a good way, then great, however for those that these things do not work well for, NO ONE should dismiss or discount the fact that they feel absolutely horrible physically. More doctors need to be trained in Neuroimmune or at least have a partial understanding so as to refer to the right providers.

If this gentleman is a scholar he should understand that no one body is the same in how it reacts to disease, virus’ or bacteria. Everyone has a genetic make up that makes them different.

I think you could compare his recovery to someone with depression.

For some behavioural approaches will lead to recovery

For some cognitive approaches will lead to recovery

For some medications will lead to recovery

For some a combined approach will lead to recovery.

For some they will remain not functioning like they used to

For some they will never ‘get better’

Arguably if you wanted to know how to recover from depression you would talk to people who had recovered.

There is a difference though between an episode of depression and recurrent major depressive disorder and more serious long standing mental health problems.

So if someone has a great recovery story using behavioural approaches we wouldn’t say ‘let’s chick out all the meds, you should all change your behaviour’. CBT for depression or BT are both evidence based but don’t work for everyone. Just like this guy – his BT worked for him but it’d doesn’t make it a universal ‘cure’.

However I also don’t think it’s helpful to question whether he was ill in the first place, if someone recovers from depression using behavioural approaches but someone else doesn’t doesn’t that mean the one who recovered was not depressed in the first place?

Good points. The same could be said for anyone who recovers from ME/cFS. Lots of different pathways which work for a limited number of people.

Just to be clear, and I don’t think you’re saying this but I don’t think of Garner himself as being depressed. Look at the guy – highly respected and productive academician who’d weathered numerous serious infections before without anything like this. He was clearly motivated to succeed – he kept trying to exercise but couldn’t and published what was going with him publicly. Those just aren’t the actions of someone with depression.

I actually think that because of Long Covid and as so many people have been affected that more research will take place into a biological/physiological/neurological cause of ME/CFS and Fibromyalgia. I had EBV in 2017 which lead to Glandular fever at 51 years old which ended up morphing into CFS/M E and some symptoms of Fibromyalgia. I was treated badly by my GP and Rheumatologist when i hadnt recovered within 6 months! Luckily for me im 95 per cent recovered now..it took two long awful years to gradually get better with many set backs.i still get relapses sometimes but not that badly and i feel better after a,week or two. I do feel angry that not enough research has taken place and the guy who apparently thought himself better should know better than to say its all in the mind! He will eat his words as will the medical profession when they finally find the physiological cause of this debilitating disease which i think they will within the next ten years.

‘I started slowly with some graded physical activity on a bicycle’

He is vague as to how long he started with. If we should listen to those who have recovered i.e. him and psychologically informed rehabilitation community. He could be more specific as to what he did for the first two weeks.

I went from very severe ME/CFS to moderate. Like others here, I practice mindfulness, paced yoga etcetc for stress reduction.

I saw Paul Garner initially having what I described as a “tantrum” about not getting better straight after Covid, making claims that this was different, it wasn’t normal. My initial reaction was that he was in a position he didn’t like or accept (post-viral fatigue).

To the outside world he seemed an authority, highlighting that Covid was an unusual and dangerous virus even for those it didn’t kill. To me, I thought he was flipping out. Especially when I read his sister has ME/CFS.

I have “mutuals” with Paul and he was out exercising soon enough. Meanwhile he became the kind of unofficial spokesperson for Long Covid, and ME almost. Yet he wasn’t “that sick” he was out doing runs of 5k and more, regularly that summer/autumn.

Then he got sick with Dengue when scuba diving abroad! Next, he’s peacocking about that he’s decided to get better, saying he had self-diagnosed ME/CFS (according to the Canadian framework for diagnosis that’s no longer used).

I told you my opinion – he had a tantrum when he didn’t immediately bounce back from Covid. A man, well qualified in his field, taken seriously. So much privilege.

Hi Cort,

The way Garner conducted himself in this instant was shameful, it came across as if he was deliberately trying to hurt the ME community. it could have not have been more badly handled by a man who had so much experience both in science and as man of medical expertise and supposed empathy.

It should be mentioned that his trip diving to Granada was by way of an invitation from Simon Wessely the main proponent of the biophsychosocial approach to ME. After not being ill for any significant length of time in ME terms, it was around this time he announced he was cured.

Garners handling of this situation left ME patients reeling from shock and betrayal and as this sort of thing had happened many times to the ME community previously from the hands of the Biophsychosocial group there was only one conclusion that we could come to about this whole sorry situation.

Do you have a source on Wessely being the person who invited him? If there’s a cite-able source for this I’d really like to know it because a documented connection between the two of them is really significant I think.

I’ve just read this whole thread. I’ve done a lot of reading (think 1000hrs+) around this trying to find any viable treatment for severe ME/CFS/Long Covid for the person I was caring for. There is not really one single comment here supporting Paul’s approach apart from it can be ‘one of many ways of getting better’. I was initially very suspicious of his approach, partly because of threads like this one. However it did work for us, once I could get past my (and the patients) state of resistance and switch to being open to the ideas. It’s still a long road that needs to be traveled and understood, but that’s the starting point. It takes quite a while to understand though, not just a quick read. I know most here will disagree, but I would have so much appreciated being pointed at this approach far earlier. I feel at least this one response in support should be allowed. I should also warn that you have to do this stuff right, understand it and talk to others who have been successful first. Harm can be done if the approach interpreted incorrectly. My NHS GP, amongst others, was very helpful in this capacity.