Longtime readers of the Health Rising blog may remember an article that Cort wrote in 2013 about the promising results of a small study that found marked reductions in fatigue among three individuals with Fibromyalgia who took high doses of thiamine (Vitamin B-1).

In the intervening years, several important studies on high-dose thiamine have been published, including a well-designed randomized controlled trial in November 2020. The publication of this landmark study provides a good opportunity to re-examine the evidence on high-dose thiamine and consider whether this supplement might be helpful for some people with ME-CFS, Fibromyalgia and Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome.

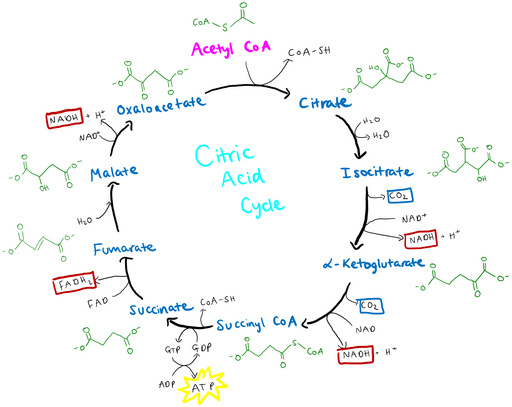

Thiamine, also known as Vitamin B-1, is an essential nutrient that plays a critical role in aerobic cellular respiration. A thiamine derivative, thiamine pyrophosphate, is necessary for the citric acid cycle to function properly and produce an adequate amount of the ATP molecules that the body uses for energy. Thiamine deficiency is a serious health problem, but most people in the western world get all the thiamine they need through a healthy diet.

The recommended daily allowance of thiamine is 1.1-1.2 mg/day. By contrast, the 2013 study on fibromyalgia used 600 to 1,800 mg of thiamine daily, more than 500 times this amount. This is the first clue that the study may involve something other than simple supplementation to remedy a vitamin deficiency.

The fibromyalgia study was one of a series of case studies published by the Italian physician, Antonio Costantini, and colleagues in 2013-2018, finding reductions in fatigue from high-dose thiamine among individuals with a range or neurological and inflammatory conditions, including Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD), Multiple Sclerosis, Parkinson’s Disease, and chronic cluster headaches.

These studies were all fairly small, and none compared the results against a control group of individuals who did not receive the treatment. Without the rigor of a randomized controlled trial, it was impossible to know for sure if the benefits were due to thiamine, the placebo effect, or some other explanation.

With the publication in November 2020 of a randomized controlled trial of high-dose thiamine by Palle Bager and colleagues at the Aarhus University Hospital in Denmark, that criticism has largely been addressed. This randomized trial confirmed the results of one of the earlier Italian studies, finding significant reductions in self-reported fatigue from high-dose oral thiamine hydrochloride over a four-week period among patients with quiescent (i.e., non-active) IBD and long-term fatigue.

In this guest post for Health Rising, I describe the results of this new study, explore potential explanations for why high-dose thiamine might relieve fatigue, and describe why I think some people with ME/CFS, Fibromyalgia, and the neurological complications of Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome (EDS) might benefit from it.

I conclude by asking those of you who have tried high-dose thiamine to complete a survey to help the field better understand whether and for whom high-dose thiamine might be helpful. If the survey results suggest that at least some people with ME-CFS, Fibromyalgia or EDS might benefit, I hope to use the results to encourage researchers to conduct a more rigorous study of its potential benefits for individuals with these conditions.

Study Results

The randomized control study found a significant decrease in fatigue in those taking the high-dose B-1.

Between November 2018 and October 2019, Palle Bager and colleagues in Aarhus, Denmark enrolled 40 individuals (35 female, 5 male) with quiescent IBD and fatigue lasting six months or more in a randomized, double-blind placebo-controlled crossover trial.

Half of the individuals were randomly assigned to received high-dose thiamine for four weeks, followed by a four-week washout period and then four weeks of placebo. The other half got the placebo first, then the washout, and then high-dose thiamine. Neither the patients nor the researchers knew who was in which group.

The study used 300 mg tablets of oral thiamine hydrochloride, assigning a daily dose by gender and body weight (BW) as follows:

- “Females: BW <60 kg: 600 mg (2 tablets), BW 60-70 kg: 900 mg (3 tablets), BW 71-80 kg: 1200 mg (4 tablets), and BW >80 kg: 1500 mg (5 tablets);

- Males: BW <60 kg: 900 mg (3 tablets), BW 60-70 kg: 1200 mg (4 tablets), BW 71-80 kg: 1500 mg (5 tablets) and BW >80 kg: 1800 mg (6 tablets).”

It is not clear whether the study participants took their pills all at once each day or spread out into divided doses, but they were advised not to take the pills in the evening due to the risk of temporary sleeplessness.

The primary outcome consisted of a measurement based on Section I of the IBD-F fatigue scale. Section I of this validated scale consists of five questions to the patient asking about fatigue over the past two weeks. To be included in the study, participants needed to have a fatigue score greater than 12, which is about 70 percent higher than the mean fatigue score of 7 in the general population. The researchers defined a reduction of 3 points or more as clinically relevant.

They found the patients’ reported fatigue declined by an average of 4.5 points while taking high-dose thiamine as compared with an increase of an average of 0.75 points while taking the placebo, a statistically significant difference. The results, after excluding three patients who had a flare-up of IBD or needed an iron infusion during the study, found a net reduction of 4.7 points in the average fatigue scale score attributable to high-dose thiamine.

There was no significant difference in results among those with and without a thiamine deficiency at the time they enrolled in the study. The finding that reductions in fatigue were not limited to those with a thiamine deficiency accords with the results reported by Costantini and colleagues across a range of conditions.

Why might thiamine reduce fatigue?

If high-dose thiamine does not work by addressing a thiamine deficiency, through what mechanism does it reduce fatigue? The short answer is we do not know for sure, but several hypotheses have been offered.

Building on a hypothesis first advanced by Costantini, Bager and colleagues suggest the possibility that high-dose thiamine may have helped compensate for a defect in the active transport mechanism through which thiamine is normally absorbed. “While the effect of high-dose oral thiamine was highly significant in our study,” the authors write, “its exact mechanisms still need to be explored and investigated. The theory of a dysfunction in thiamine transport from blood to mitochondria remains a plausible explanation.

The participants in our study were exposed to high doses of thiamine which induces passive diffusion that will add thiamine to the cells and the mitochondria. Consequently, the carbohydrate metabolism can normalize, and a reduction of fatigue is likely to follow.”

In a recent comment on a blog post, noted thiamine expert Derrick Lonsdale offered an alternative hypothesis to explain what he terms as the “miraculous” clinical effects of high-dose thiamine.

“[T]hiamine, and particularly its derivatives, are being used as ‘drugs’. It is nothing to do with simple vitamin replacement. The enzymes that require thiamine have been deprived of it for so long that it can be expected that they have deteriorated ‘physically’ in their metabolic responsibility. The cofactor has to be used in megadoses in order to stimulate the enzymes back into their normal function.”

As Lonsdale acknowledged, this hypothesis still needs to be evaluated through research.

In a letter to Alimentary Pharmacology and Therapeutics, the medical journal that published Bager’s study (the authors’ reply is here), I offered a different hypothesis that builds on two other recent studies of high-dose thiamine.

In 2013, Özdemir and colleagues found that high-dose thiamine inhibited three carbonic anhydrase isoenzymes nearly as well as acetazolamide (Diamox). Inn 2021, Vatsalysa and colleagues found that high-dose thiamine tamps down the pro-inflammatory Th-17 pathway believed to play a role in the COVID-19 cytokine storm.

Building on these findings, I propose that the benefits of high-dose thiamine in relieving fatigue and generating other symptomatic improvement in patients with a diverse range of neurological and inflammatory conditions may be due to thiamine’s role as a carbonic anhydrase inhibitor.

I hypothesize that the benefits accrue through one or more of four potential pathways:

- by reducing intracranial hypertension and/or ventral brainstem compression;

- by increasing blood flow to the brain;

- by facilitating aerobic cellular respiration and lactate clearance through the Bohr effect; or by

- tamping down the pro-inflammatory Th-17 pathway, again through the Bohr effect, possibly mediated by reductions in hypoxia-inducible factor 1.

This is a lot to unpack, so let me offer this high-level overview, and refer readers interested in the technical details to a blog post I wrote on Medium that explains my theory in more detail, with full citations.

Could high-dose thiamine help with blood flows to the brain, intracranial hypertension and aerobic functioning?

In a nutshell, I am proposing that taking high-dose thiamine is a lot like taking Diamox (the brand name for acetazolamide – the most common treatment for intracranial hypertension, but without many of the worrisome side effects. Rather than working by addressing a vitamin deficiency, high-dose thiamine operates by reducing intracranial hypertension (and possibly ventral brainstem compression as well) through a reduction in cerebral spinal fluid.

In the process, by inhibiting carbonic anhydrase isoenzymes, high-dose thiamine produces carbon dioxide, which leads to increased blood flow to the brain and an increase in the availability of oxygen at the cellular and tissue levels for aerobic respiration, reducing reliance on anaerobic respiration and helping to clear lactate. By reducing hypoxic conditions, the increased oxygenation also reduces the levels of a mediator (hypoxia-inducible factor 1) that triggers the pro-inflammatory Th-17 process, helping to counter inflammation.

I will be the first to admit that these ideas need to be carefully evaluated through rigorous research. My goal in proposing these hypotheses is not to offer them as gospel but rather to stimulate research into the mechanisms through which high-dose thiamine operates. These mechanisms are important both for predicting the potential conditions that high-dose thiamine could help treat and for clarifying the limitations and cautions that should be applied to its use.

The hypothesized mechanisms I describe above are alternatives in the sense that one or more may be accurate while the others may be inaccurate. It also may be the case that some individuals benefit through one mechanism while others benefit through another mechanism, which may help explain why people with a wide range of conditions report benefits from high-dose thiamine. Some individuals may even benefit simultaneously through multiple mechanisms.

Could high-dose thiamine help people with ME/CFS, Fibromyalgia, or EDS?

More research is needed to answer this question definitively, but I believe we know enough to suspect this research would be worth conducting. The 2013 study by Costantini and colleagues finding benefits among people with fibromyalgia provides a basis for conducting a larger and more rigorous study of the potential applications of high-dose thiamine for people with fibromyalgia.

Similarly, the case reports and discussion included in the Driscoll Theory provide a basis for follow-up research on the potential benefits of a carbonic anhydrase inhibitor like high-dose thiamine for people with certain neurological complications of EDS. Driscoll’s book argues that people with some neurological complications of EDS can benefit from acetazolamide (Diamox). She attributes the results to reductions in intracranial hypertension, a known complication of EDS. I wonder, as well, whether a carbonic anhydrase inhibitor could help with ventral brainstem compression caused by Craniocervical instability and Chiari malformation.

The case for predicting the benefits for people with ME/CFS is more circumstantial. A 2020 study found signs of possible intracranial hypertension in 83% of 205 individuals with ME/CFS that had an MRI performed. The reductions in cerebral spinal fluid achieved through a carbonic anhydrase inhibitor like high-dose thiamine might potentially be helpful for individuals with these and other neurological conditions.

There is reason to believe that some of the other pathways may also apply. For example, many individuals with ME/CFS have reduced blood flow to the brain. As Cort has summarized in past blog posts, this might be related to the finding in several studies of reduced levels of CO2 in people with ME/CFS. The authors of these studies hypothesize that these reduced CO2 levels may be narrowing blood vessels, constricting the flow of blood to the brain. By producing CO2, high-dose thiamine could potentially remedy this problem and improve blood flow to the brain.

The Gist

- A randomized-controlled trial of high-dose thiamine found that it reduced fatigue in people with quiescent IBD.

- The outcomes did not differ for individuals with or without a thiamine deficiency at the start of the study.

- The exact mechanism for thiamine’s effects on fatigue is not clear. The author of this post hypothesizes that high-dose thiamine’s effects might be due to its role as a carbonic anhydrase inhibitor, which could reduce intracranial hypertension and produce CO2 that increases blood flow to the brain, tamps down the pro-inflammatory Th-17 process, increases aerobic respiration and clears lactate.

- There are reasons to believe high-dose thiamine could potentially help people with ME/CFS, Fibromyalgia and the neurological complications of Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome. Rigorous research is needed to assess whether this might be the case, and if so, who is most likely to benefit.

- Carbonic anhydrase inhibitors are powerful medications that have the potential to interact with a number of other medications and supplements.

While a preference for anaerobic respiration is apparently common among people with ME/CFS, this is often attributed to mitochondrial issues, and I am not quite sure how a carbonic anhydrase inhibitor could help with this. (The passive transport theory articulated by Bager and Costantini might potentially be useful, however.) On the other hand, the production of carbon dioxide through carbonic anhydrase inhibition could potentially help to improve lactate clearance, which Vink identifies as a problem in ME/CFS.

Hopefully, future studies of the potential benefits of high-dose thiamine for people with ME/CFS, fibromyalgia and the neurological complications of EDS will go beyond studying the general concept of “fatigue” to assess a range of more specific outcomes. Potential benefits could include improvements in mental acuity / brain fog and certain kinds of headaches – due to reductions in intracranial hypertension – and reductions in post-exertional malaise due to increases in aerobic respiration and lactate clearance.

While it is just one case, my daughter, who has EDS, craniocervical instability and chiari malformation, appears to have experienced improvements in brain fog and post-exertional malaise from high-dose thiamine (though at particularly high doses of thiamine, she actually reports an increase in general tiredness).

To help bolster the case for conducting a rigorous study of whether high-dose thiamine benefits individuals with ME/CFS, fibromyalgia, or the neurological complications of EDS, it would be helpful to learn more about whether individuals with these conditions have benefitted from high-dose thiamine. Please don’t start high-dose thiamine just to participate in this survey, but if you have already tried high-dose thiamine (which I define as a daily dose of 200 mg or more or oral thiamine), and feel comfortable completing this survey, please go ahead and do so.

Please complete the survey whether your experience has been positive or negative. I will summarize and report out the results in a future column.

Cautions and Limitations

If I am right that high-dose thiamine is a carbonic anhydrase inhibitor with a potency approaching acetazolamide, there are many cautions that should apply to its use. These include the risk of potassium deficiency (particularly if combined with a diuretic, including herbal diuretics) and the potential to form kidney stones. The combined use of high doses of aspirin and acetazolamide (another carbonic anhydrase inhibitor) has been reported to lead to salicylate toxicity. And people with intracranial HYPOtension would likely feel worse from high-dose thiamine, even as people with intracranial HYPERtension potentially feel better.

Driscoll reports a phenomenon in which acetazolamide sometimes stops working after a period of time. This phenomenon is also reported in the older literature on acetazolamide, which also describes a general malaise that appears to be related to mild acidosis. The older literature reported the problem resolved with sodium or potassium bicarbonate, though acetazolamide today comes with a warning against the routine co-administration with sodium bicarbonate due to the risk of kidney stones. In addition to taking sodium bicarbonate, Driscoll also recommends lowering the dose.

Finally, there is some suggestion that thiamine may be a histamine liberator and DAO inhibitor (though in theory, reductions in intracranial hypertension and brainstem compression could potentially lead to improvements in MCAS symptoms). My daughter seems to have experienced some shifts in food tolerance after starting high-dose thiamine, but no marked improvements or worsening.

This all suggests the importance of clarifying whether high-dose thiamine really is a carbonic anhydrase inhibitor as predicted by Özdemir’s 2013 in vitro study, and providing clear guidance to practitioners and patients on how to avoid or reduce complications.

For more discussion on the potential of high-dose thiamine to help people with ME-CFS and the neurological implications of EDS, including full citations, see my Medium post on this topic.

Jeffery is a father of a daughter with ME/CFS and allied disorders.

About the Author

I am the parent of a teenage daughter who has been diagnosed with Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome, hypermobility type; Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome; Mast Cell Activation Syndrome; and Chronic Fatigue.

I have prepared this post to stimulate further research, and not to provide medical advice. I am not a medical professional and do not have medical training.

@Jeffrey Lubell: Thanks so much for your great overview of the effect of high dosis B1 supplementation on FM/ME/… diseasses.

Issie and I have been discussing her improvement with high dose B1 more then once. I am weary to use anything dosed so much higher then daily recommended doses or needs as it has the potential to crowbar key biological processes. Yet, I cannot deny many patients are reporting significant differences when taking those high doses.

Based on what you wrote and some quick search, I have two things I consider making a chance to be rather important here.

One you reported was:

“In 2013, Özdemir and colleagues found that high-dose thiamine inhibited three carbonic anhydrase isoenzymes nearly as well as acetazolamide (Diamox).”

=> Would by chance people who start to take high dose B1 within a few days feel a really remarked and even outspoken ability to breathe, to get oxygen from breathing and feel an ease of breathing they didn’t had in a long time, to need to hyperventilate so much less then before?

If possible, I’d like to see as much answers yes or no or some relevant comments to this question. The answer to it may be rather important to further understand what is at work with both high doses of B1 and even ME/FM diseasses in general I believe.

So: thanks in advance for all willing to reply. Don’t hold back to report either yes or no answers, we need not only successes to be reported.

Thanks for the note and your question. I am glad to hear Issie is benefitting from high-dose thiamine! The short answer is that what you describe may well be possible, but more research would be needed to confirm. Much has been written about the use of acetazolamide as a respiratory stimulant, particularly for individuals with COPD and in connection with Acute Mountain Sickness. To the extent thiamine is a carbonic anhydrase inhibitor similar to acetazolamide, it may well help in these circumstances as well. However, there are debates about the precise mechanisms through which acetazolamide operates and some believe that carbonic anhydrase inhibition is only one of the mechanisms, so it’s possible thiamine may not do everything that acetazolamide does. The field would very much benefit from a study of the potential of high-dose thiamine to serve as an alternative carbonic anhydrase inhibitor. In the meantime, I am trying to collect information on peoples’ experiences with high-dose thiamine, so if this has been one of the effects, it would be helpful to record this in the survey. Thanks again for your interest.

It’s pretty clear when carbonic anhydrase is being inhibited…carbonated beverages all taste flat. Diamox produces this effect strongly. Topiramate, a milder carbonic anhydrase inhibitor, also creates a milder form of this altered taste sensation. However, I get none of this from high dose thiamine, even up to 400 mg/day by injection. This leads me to wonder if it is really inhibiting carbonic anhydrase at all?

I’m involved with Dr Chandler Marrs’ group on Facebook, Understanding Mitochondrial Nutrients and am very familiar with her work as well as Dr Lonsdale’s. It’s clear that thiamine has the potential to help at low risk, which is reason enough to try it in my opinion.

@remy — it is possible that carbonic anhydrase is not being inhibited in vivo — it should certainly be studied empirically. However, there is evidence that it is being inhibited in vitro. See Özdemir, Z.O., Şentürk, M. & Ekinci, D. Inhibition of mammalian carbonic anhydrase isoforms I, II and VI with thiamine and thiamine-like molecules, Journal of Enzyme Inhibition and Medicinal Chemistry (2013), 28:2, 316–319.

hi please could the author send me a private message i really need to speak with you i have M.E fibro hEDS i would really like to talk to you i am really struggling i am on facebook or gmail

It didn’t seem to have made a difference either way to my breathing. But my PEM and fatigue totally disappeared in about 2 days. There is another key factor for me though at that is B12. I take 200mg B1 & B2 daily and if I take more that 33mcg B12 the fatigue will come back. I do not have full MTHFR but do have a few notable genetic issues along that line.

Good to know you’ve had some benefit!

If you feel comfortable completing the survey on high-dose thiamine, it would be helpful to be able to include your experience. Thanks for considering. https://forms.gle/y2ZV8yqk3wUw9rph6

Take non synthetic b vitamins only. I tolerate adenosylcobalamin the best.

I’ve tried this approach several times over the years. It’s always made me feel worse.

B-12 and particular forms of B12, on the other hand, have been helpful.

Thanks for the report. I am interested in learning more about why high-dose thiamine appears to help many people with ME/CFS, Fibromyalgia, and EDS, but makes a small share feel worse. So far, it appears that it may negatively affect people with CSF leaks or other forms of intracranial HYPOtension, as well as people with severe MCAS or active MCAS flares. Also, some people felt worse on some forms of thimaine but better on another.

How long did you take the high dose thiamine, and did you titrate up slowly? I am trying it for severe long haul Covid which is manifesting for me much like ME/CFS (severe fatigue and PEM that have left me bedbound for two years) but also with many neurological symptoms like all over tingling and numbness, twitching and jerking of muscles, tinnitus, gastoparesis, and POTS, as well as MCAS. I decided to try thiamine based on reports that in many people, long haul Covid resembles beri beri, a disease of thiamine deficiency. I prepared by reading extensively about dosing strategies and pitfalls, especially on the website hormonesmatter.com. There is much information on that site from high dose thiamine pioneer Dr. Lonsdale about the phenomenon of paradox, basically that some people feel a lot worse when starting thiamine before they start feeling better. Controlling paradox symptoms involves backing off to lower doses, titrating up VERY slowly, and making sure to include relevant cofactors. It has been a lot of trial and error and has taken me over two months to build slowly to only 400mg of thiamine HCl. I still battle mild paradox symptoms every time I increase dosage but it is manageable and subsides within a few days. I wonder how many people who have said they felt worse on thiamine may have been experiencing paradox that could be managed by the techniques I mentioned above. It does mot sound like the participants in the study were titrated up or given cofactors. Dr. Lonsdale’s belief is that the presence of paradox is actually the best predictor of successful treatment.

Oh wow! I decided to start low, but I just started with 500mg! Maybe I should lower it more.

The second, but highly technical possible link I see is:

Thiamine seems to modify an important enzyme called p53 and that has research linked to ME, Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD), Multiple Sclerosis, Parkinson’s Disease (all diseasses reported above in this blog to be possibly improved by high dose B1). Research papers on the link between all those and p53 can be found by Googling for ” P53″. It’s a bit too cumbersome to link all the finds.

As to thiamine and p53, two important finds are:

“Thiamine antagonists trigger p53-dependent apoptosis in differentiated SH-SY5Y cells” from “Sergiy Chornyy, Yulia Parkhomenko & Nataliya Chorna” published in Nature (one of the very best science magazines on the planet).

Apoptosis is a rather strong form of cell death so it’s rather strongly related to inflammation and anything affecting apoptosis might be important in highly inflammatory disease like ME/FM/IBD/MS/PD.

Another paper linking thiamine and P53 is:

“Chapter 11 – Analysis of the Protein Binding Sites for Thiamin and Its Derivatives to Elucidate the Molecular Mechanisms of the Noncoenzyme Action of Thiamin (Vitamin B1)” From “V.I.Bunik, V.A.Aleshin†”

Saying “Noncanonical thiamin-binding proteins of systemic significance include p53, PARP1, signal-related phosphatases, and kinases. Coupled to coenzyme actions of thiamin in central metabolism, the thiamin binding to noncanonical proteins may well provide for systemic regulation by thiamin-dependent signaling cascades, similar to those involving essential metabolites, such as ATP and NAD+.”

P53 is involved in regulating apoptosis, gene expression and protection DNA from mutations and PARP1 is involved in inflammation pathways and involved in DNA repair.

Very interesting. I’ll take a look! One thing I would note in general is that thiamine is an extremely important nutrient that plays multiple essential roles in cellular energy production. I personally think that this fact has served as an obstacle to researchers considering that high-dose thiamine may be operating as a drug through a mechanism that is entirely different from its essential role as a nutritional supplement. As research moves forward, I think it will be important to distinguish between effects seen in cases where thiamine is remedying a nutritional deficiency and effects from high doses of thiamine where there is no baseline deficiency.

As thiamine hydrochloride contains aluminum which may build up in the brain and kidneys, I choose to take probiotics and natural forms of thiamine B1, as i am chemical sensitive. When I first started on thiamine I wasn’t aware that the hydrochloride version was more like a pharmaceutical drug. I took 300mg of the hydrochloride thiamine for just 2 days and both days I suffered which extreme headaches, I have been diagnosed with fibromyalgia over 20 years ago when very little was known about it and due to my chemical sensitivity I am unable to take pharmaceutical drugs. Although I have many symptoms of fibromyalgia, headaches have never been a thing for me. This is what lead me to think something wasn’t suiting me with thiamine hydrochloride as I had changed nothing else in my diet, and when taking this version of thiamine I stopped all other supplements in order to see if thiamine helped. On the 3rd day I didn’t take the hydrochloride thiamine and i had no headache. I then decoded to start on thiamine monophosphate, which is reported to be less absorbed, but as I was aware of the need for healthy gut bacteria in order to absorbe vitamins in the intestines I just increased probiotics.

I’m only 3 days in using this form of thiamine and yesterday I had more energy than I have in the past 2 years, as my fatigue as become excessive in that time.

Not sure if this is a Placebo effect as yet and will continue with the supplementing.

As you are pondering on why thiamine helps some feel better but some feel worse I questioned whether this may be due to aluminum build up. Small amounts of aluminum are found in food, water, toiletries, cosmetics, pharmaceutical drugs etc. Therefore, each individual will have different levels in their system, with differing tolerance levels and symptoms. Therefore adding to this in mega dosing may be a possible explanation.

I love the potential oxygen connection…and the blood flow connection…and the intracranial hypertension connection come to think of it. Thanks to Jeff for doing all this work and coming up with something interesting to chew on.

Speaking of B vitamins, the one B that I’ve always noticed helped was B-3 (niacin). A good flush is temporarily calming, mildly energizing, cognitively enhancing and helps with chemical sensitivities.

Interesting. What dose of niacin seems to help?

There’s a very interesting Facebook b12 deficiency group.

The protocol means you have to use oils instead of oral b bits if possible.

But there is a dosing protocol.

First you must be replete in molybdenum, potassium iodide and selenium.

You must be replete in these before you start dosing B2. B2 is the start of the cascade that allows you to process the other vitamins and get b12 up and running

I can’t afford to apply the protocol. But there are bed bound people who have fully recovered with the protocol.

There is a big problem with adrenaline reactions which must be treated with potassium..it is quite amazing how potassium does that, when I’ve messed around with b bits.

I don’t understand the ins and outs of the protocol fully. I know the scientist behind it has presented to the omf.

I know you’re looking at b1. Just thought I’d mention this

Is taking thiamin nitrate the same as thiamine HCL ?

@nerida, Thiamine mononitrate is not the same thing as thiamine hydrochloride. However, it is easier to find, less expensive, and could perhaps be as effective. The problem is that we just don’t have as much data on thiamine mononitrate and don’t know how well it is absorbed into the body compared with thiamine hydrochloride. Before we started thiamine hydrochloride, my daughter was using thiamine mononitrate, and it seemed to have a large positive effect. We switched to thiamine hydrochloride because there were studies on its absorption and on its effectiveness, so we thought that would be a more reliable base on which to build. But future studies should certainly look at the pharmacokinetics of thiamine mononitrate and on its effectiveness compared with thiamine hydrochloride.

I recently (and accidentally) found that I get a huge benefit from 1750mg thiamine nitrate. Before trying long term supplementation, I’m first learning about the various cofactors and required dosing of those.

When on thiamine nitrate, it seemed as though every cognitive process was improved, as well as emotional regulation. Paradoxically, there was also some occasional underlying aggression/anger, but this may have been due to concurrent folinic acid mega dosing.

I’m not sure why I haven’t just ordered the necessary cofactors, I think maybe just being too cautious and also, it seems too good to be true. Motivation was increased, PEM almost non-existent, my drive to socialise was much higher, executive function greatly improved…..

Alright, time to get on iHerb and make a new order 🙂

Good luck! 🙂 Please keep us informed!

Will do, and thanks! Is there any longer term data available either from this study or from individual cases? It’s another aspect contributing to my hesitancy, that we don’t seem to hear from people having success for say 2-3 years or more.

Did you have a trial of this, Cort? I think I remember reading a comment of yours about this my not sure my recall is accurate….

I don’t remember one.

There was a subsequent study that followed up on these individuals through one year and tested impact of a lower maintenance dose of thiamine. It found no statistically significant impact of the lower maintenance dose but did find that individuals who took some thiamine between weeks 24 and 52 had lower fatigue scores than other patients, suggesting to the authors that patient self-regulation / self-medication was effective. Bager, P., Hvas, C. L., Rud, C. L., & Dahlerup, J. F. (2021). Long-term maintenance treatment with 300 mg thiamine for fatigue in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: results from an open-label extension of the TARIF study. Scandinavian Journal of Gastroenterology, 57(1), 37–43. https://doi.org/10.1080/00365521.2021.1983640.

There was another trial recently examining high-dose thiamine in patients with primary biliary cholangitis that found no impact. But it was extremely underpowered (36 patients total). As supportive as I am of randomized controlled trials, I think it is problematic to do these very small trials where you don’t really know how to interpret the findings. Did it fail to show a significant impact because it didn’t work or because the sample was too small?

While not a trial, this article summarizes the initial results of a survey I did on use of high-dose thiamine by patients with ME/CFS, EDS and fibromyalgia through Health Rising. https://www.healthrising.org/blog/2021/06/02/fibromyalgia-chronic-fatigue-syndrome-benefit-high-dose-thiamine/

I kept the survey open and then updated my analysis of the the survey results after getting 108 responses, The responses are summarized here. https://twitter.com/JeffLubell_C19/status/1638097484047163393 . And here: http://www.high-dose-thiamine.org/results-of-high-dose-thiamine-survey/

cort, i’ve taken high doses of B-complex for many yrs. is 100mg. high for B-1? i don’t know.

I really appreciated this blog, article, and information!

I have fibromyalgia and RA. In addition to significant injuries from an auto accident. The Insurance on the individual causing this “head on crash”, wasn’t sufficient to provide the necessary treatment for relief.

I will increase B-1 immediately and if you’d like will report my findings. Feel free to contact me.

Thank you again!

Yes I also would be interested in your dose please!

The Wahls protocol promotes eating organ meat as a potent source of B vitamins. You can even buy grass fed organ meat, dehydrated and in pill form.

Great article, thank you Jeffrey!

@Jeff Lubell Thank you for this informational post on high dose thiamine.

It is very wise to gather information, including doing testing to figure out if one has the problems you are pointing out, and one is suffering from thiamin deficiency. Too much thiamine can have some very negative consequences, so it’s good to know if one is solving the right problem. You do make some good points.

I’ve done very well on 750 mg of Benfotiamine daily. Now I’ve heard the folks who say that it doesn’t get into the brain, but I don’t have any mood or brain problems currently, and I think it’s worked really well and is somehow getting into my brain.

But, swayed by followers of Derek Lonsdale who banged the drum of taking specific forms of thiamine, namely TTFD or allithiamine, I decided to try their method. None of them could tell me any kind of conversion between the different forms of thiamine, so I decided to be conservative and tried 300 mg of Thiamax, one of the forms that was so highly touted.

Much to my surprise, I develop neuropathy in my hands and feet within 4 days of taking the stuff. It took me a couple of weeks to figure that out, and I dropped them and all together, and gradually added back in my benfotismin over a month, and it took the full month to reverse the thiamin caused neuropathy.

Neuropathy can become irreversible, and I was lucky to have nipped it in the bud. I’ve had a clear brain, and seem to be getting benefits from the benfotiamine I’m taking, I’d have never tried the version you discuss from the studies.

A friend suggested someone had said that people who tend to be low in glutathione, which is typical of many ME/CFS patients, who are known to have excessive oxidative and nitrosative stress, can develop this sort of neuropathy from B1.

Seems like there’s a lot to be learned about thiamine, but I do know that it has been shown to be effective in resolving the high lactate that many and me/cfs patients experience.

Thanks for sharing your experience. I do not have any experience with the fancier forms of thiamine. The research studies that I have seen on thiamine all used thiamine HCL, which is a fairly simple low-cost version. When administered regularly, within a week, it produced blood levels of thiamine that were similar to IV administration. The main difference was a lag of several days. In the survey responses, I have seen some people prefer benfothiamine and some thiamine HCL; some people report feeling better on one than the other. I am looking forward to learning more about peoples’ experiences.

Dear Jeffrey,

Thank you for all of this information! It’s so nice to have people posting who are NOT struggling with low blood flow to the brain…:(

If you don’t mind sharing, who diagnosed your daughter’s EDS and other conditions? It would be very helpful to know where to find some of the doctors that are, well, hard to find. Especially with the hypermobility version, for which there is no definitive test.

The reason for the allithiamine, from what I have read, is that it is capable of crossing the blood/brain barrier. So while other forms of thiamin might be just as effective for physical energy and other benefits, the allithiamin is better at reaching the brain for those with significant cognitive issues.

I just ordered some, so I will let you know how it goes. I will have to tinker with the dose and based on one of these posts I may wait until my glutathione levels are confirmed before I start. The allithiamine only comes in 50 mg so, rather than taking half the bottle to get to a high dose, I will add some thiamin HCI to get the “high dose” , with the allithiamin to get into my brain. We shall see.

By the way, another published paper on NIH indicated that bentofamine DOES NOT cross blood brain barrier, but of course, studies need to be repeated to confirm.

I don’t really understand the role or process of inhibition of the carbonic anhydrase, other than the effects of reducing intracranial hypertension. I am one of the few ME patients that has crazy HIGH blood pressure instead of very low BP, but it can also get pretty low…wild swings, not well controlled. I suspect due to dysautonomia. I’m sure it can’t be due to me forgetting to take meds………… Anyway, hopefully this might help with all that, too.

Have also read that it is not unusual to herx or feel worse initially with B1 (especially starting with a high dose), just like with any other medicine we might take. But the terrible neuropathy got my attention so I will just go very slow, as usual.

I will need to re-read everyone’s posts multiple times! But I want to thank @Remy for sharing how you can tell based on fizzy drinks, what a great piece of information. Thanks to all

If you feel comfortable completing the survey on high-dose thiamine, it would be helpful to be able to include your experience. Thanks for considering. https://forms.gle/y2ZV8yqk3wUw9rph6

Wow, very interesting that the TTFD caused neuropathy! I had just ordered some in hopes that it would help with my neuropathy. I just now ordered the Benfotiamine. I think I will try it first after your experience. it is a possibility that you are missing other co-factors that might have negated this side effect. Thanks for sharing your experience.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-DxvSUEVT_4

Tracy, Make sure you also supplement with a really good Glutathione supplement. We use HydraStat Molecular Encapsulated Glutathione. We are on High dose Benfotiamine and TTFD depending on what we test for on a daily basis.

TTFD takes more cofactors to cleave the thiamine from other components in TTFD and it involves the Glutathione and Methylation pathways more than other forms of Thiamine, so for some people will result in what Dr. Londsdale calls “Paradox” (things like neuropathy, etc). Elliot Overton suggests building up some of these other micronutrients and electrolytes first and then taking things low and slow. More info: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-DxvSUEVT_4

Everything I’ve read about supplementation when you’re obviously not well is to go low and slow because of paradox – where a person gets worse before they feel better. I develop neuropathy with ME/CFS alone (I suspect thiamine deficiency now). The idea is you start off at a tolerable low dose and don’t ramp up until those symptoms resolve.

“None of them could tell me any kind of conversion between the different forms of thiamine, so I decided to be conservative and tried 300 mg of Thiamax, one of the forms that was so highly touted.“

I’m not sure what you mean by the conversion between different forms? If you ask this question on the Facebook group, perhaps Dr Marrs can answer for you. As far as I know, they don’t interconvert and have differing structures.

300 mg of allithiamine (Thiamax) is a whopping big dose. Most people start with 50 mg (or even less). Thiamine refeeding syndrome is common when starting and leads to an exacerbation of thiamine deficiency symptoms.

Symptoms from high dose TTFD can be a bit scary; it’s suggested that much of what people experience is re-feeding or paradox. Here’s a weird paradoxical reaction I’ve had since beginning TTFD. Background: in 2000 I stopped having an allergic reaction to airborne pollens (had had them since I was a kid and I was then 45). I thought it was perhaps a sign I was getting better, but two years later ME/CFS disabled (I’d struggled much of my life). This means except for one virus I’ve literally not sneezed and I used to have at least one sneezing fit every day of my life. Thiamine deficiency increases histamine. Three weeks after starting TTFD I’ve begun to sneeze again. It’s almost as if things had shut down so much that the only time I had a histamine reaction was the result of being bit by an insect or from ingesting food I’m allergic to. Now, it’s almost as if my body has enough thiamine to register a deficit. I’m hoping I’ll move through this. Neuropathy is a sign of a thiamine deficiency. Don’t know the answer to what you’re experiencing, but my own experience makes me wonder.

Also, I have glutamate/gaba issues as many of us with ME/CFS do. Thiamine will increase both glutamate and gaba and so I found myself with too much glutamate (given that I have trouble with that). Not only was I experiencing anxiety but tetany, which I’d gotten rid of the year before with magnesium. I suspected that I’d already added enough magnesium to support the TTFD and went to look for another answer. Vitamin B6 – I have mutations – I added the extra B6 (in addition to what’s in the B complex and my multi) and that’s been brought under control. I also found out in my stumbling around that B2 (yep, mutations might be playing a role) is important with both MTHFR and glutathione recycling (or whatever that’s called). Having MTHFR and MCS, I realised I needed to take extra B2. When taking TTFD, it’s important to take a B-complex, a multi, have adequate extra magnesium, support glutathione, and ensure you watch your electrolytes in general (as one or more can become depleted but particularly potassium). Lowered potassium can result in tingling and numbness. Many find they have to supplement potassium or eat some foods high in potassium daily.

I’m only about 6 weeks in on this journey and so far am managing to figure out what I need based on my symptoms.

I will comment on this as I have EDS, ME/CFS, MCAS, POTS and the list continues.

I tried the Diamox when it was first suggested as a help for both EDS and POTS. In earlier days of discovery some of us would try anything and everything to feel better. It was also said that we were to take baking soda with it as it could imbalance alkaline levels and add more dysfunction in other ways. And it tends to somewhat dehydrate you and it is a type sulfur (with methylation issues can be a potential problem). One other reason to try was, I also had the feelings of my brain being swollen and like if I could take my hands and squeeze my head and get fluid out, it would feel better. Also had a sense of pressure behind my eyes. At first it felt helpful. But then it started going wrong. I have low fluid volume due to POTS and this was a type of thing to pull off fluids. I also have low renin and aldosterone and less fluids with that problem and this being low affects the kidneys. My kidney function went into Stage 3 Chronic Kidney Disease when I did Diamox. Whether it is what contributed to it or it was just going to go that way……I can’t say. But long run, Diamox made me much sicker and my POTS did not get better, and neither did my EDS. (To fix this Stage 3 CKD, I became a strict vegan for 3 1/2 years and reversed it to stage 1 now. I’m no longer vegan, but my kidney function is holding level.) So personally, this was a failed experiment.

Now to using B1. I had tried the more synthetic version of it and find the traditional B1 is the one that helps me the most. In fact I feel it helps so much, I have told Dejurgen its one of my “must haves” of the things that are on that list of keepers. I will tell how I got to this. I tried it back in the early days of my DX with POTS as some were finding it helped. But I used the more synthetic version and didn’t find that much benefit, evidently, as I didn’t stick with it. But in the last few years I started having severe muscle weakness. I mean where I could not get up from a chair and was having to use a cane as I was so unsteady. And then I had one eye to start crossing. Just sort of go off to the side when looking straight ahead. I caught this with a selfie and showed my doctor. There are 3 things that I knew of that could cause this. One was mental illness, which I don’t have. The other was a brain tumor, which I DO have. I have a progressive menigioma that we keep a watch on. And it can cause neurological issues and personality changes…..which could had been a possible cause because of the progressive leg weakness. But I didn’t have headaches or personality changes. And the other possible thing was a lack of B1. So my Functional doc and I discussed and we both decided to address the easiest first and try B1. This has all been since COVID you guys, so I wasn’t eager to have a 45 minute lay in an MRI for a brain scan, with me having Hypogammaglobulinemia and not being able to fight off things. So I started B1, the normal type. Long story short. My leg weakness has improved to the point of my no longer needing a cane to walk. My eye doesn’t cross. I have more energy and I am better with all things. I am not well however. But B1 along with other things I’m doing is improving me. (I still have to get that MRI, as we have to keep a watch on that brain tumor. But so far, so good.)

Now as for increasing CO2. I’m doing that too but in a different way. I don’t think my taking 100 mg of B1 a day is what is doing that. (There are other supplements I credit for my improvements over all too.) But I also had severe apena. Not just obstructive but central. That is where my brain doesn’t tell me to breathe. I have been retraining myself to breathe differently. How? I use a criss cross tape that you put on top of your lips to sleep at night. When you put the tape on, you sort of poke your lips out and make sure your tongue is to roof of your mouth. Apply tape in center. (Make sure and use lip balm first.) What that does is it juts your lower jaw slightly forward. And it forces you to breathe through your nose. It also slightly increases your CO2 when you do this and it slow your pace of breathing down. That helps the CO2 to carry more oxygen into the cells. And they all work better. It helps you not have as much hypoxia. If you are a mouth breather or you snore. This will help that. I no longer have to wear a CPAP. I have a new Fitbit watch and it measures my oxygen that is on average 94% but ranges between 92% and 98%. I have good range of sleep patterns between REM, LIGHT and DEEP sleep. And it shows my breathing patterns well within normal. I have few wakes in my sleep not indicating any apena sessions. I don’t wake with headaches or dry mouth.

Now as for sleep, and I talked of this before. I MUST, MUST raise my head to sleep. It is important for the drainage of the brain to have that gravity to help that ….for me. Otherwise I have that head pressure and poor sleep. I raise the head of the bed on blocks to have the whole bed slope. And then I put another larger pillow under me to raise my head slightly more. For me with EDS the kind if pillow that gives me the most support and comfort and I can squish down into it and be fully supported is a Microbead pillow. (I like Tony Littles the best. But not cheap and there are good cheaper ones on Amazon.)

Sooooooo, long story to get to this conclusion…….B1 is one of my “Must haves”!

Thanks for sharing your experience. Very helpful! If my hypothesis about thiamine being a carbonic anhydrase inhibitor is correct, I do think that kidney function is something to monitor regularly on high-dose thiamine, just as with Diamox. I would very much like to find a nephrologist willing to put out some common sense guidance on how to minimize the risk of kidney stones from high-dose thiamine, based on their experience with Diamox. One place to start might be simply with drinking more water.

Since I take only 100mg. I don’t guess I qualify to participate in the survey. But I would say its helpful.

how much b-1 in mg. do u take a day?

My daughter currently takes 1,125 mg daily. Several of the research studies on high-dose thiamine varied dosage by weight and gender.

Have you ever gotten tested for obstructive sleep apnea and Upper Airway Resistance Syndrome?

Both lead to intracranial pressure and other neurological complications, particularly as it relates to dysautonomia, and sleeping with elevation is the 101 of managing these sleep breathing disorders.

80-90% of people with OSA are also undiagnosed. Many get misdiagnosed due to sleep studies being scored with insensitive scoring criteria too.

Hey Issie, I’m new to this thiamine thing and just did a bunch of research in the last several days. I have chronic ebv with liver and spleen pain. I have also, recently, had an intense midline pressure upon laying down (abdomen up through chest) as well as heart pain radiating into left shoulder and left jaw. The pressure got so intense 2 days ago I almost went to the ER fearing I was having a heart attack. I started thiamine 2 days ago for apnea and glucose issues and lo and behold…I am a different person today. I feel incredible! Last night…no chest pressure, my breathing changed..I could freely breathe by laying down. I am shocked and excited. The sense of doom that I’ve had for months has just vanished, literally overnight. I’m taking Benfotadine 50 mg thiamine and 150mg Benfotidine…twice daily.

So heres the part I thought important to share with you. It appears, specifically in regards to cancer, that thiamine supports health at higher doses and supports cancer cell proliferation at lower doses. So far it appears that over 200mg a day may be considered high dose but it may, in fact, be different for your type of cancer.

I currently have concerns that i have lymphoma (from ebv) . I’m currently getting labs. So I am doing some detailed reading about the use of thiamine in conjunction with cancer.

Honestly I feel I just subverted a heart attack with the thiamine so I am going to try to find the balance between supporting my heart but not agitating any possible cancer stuff. I will include the article I read about the importance of finding the right high dose of thiamine for the type of cancer you have. I wish you the best. Thank you for sharing your story.

Here is the segment from the document..its a beefy document. I’ll include the link below too so you can scan through the whole thing, if you like, for pertinent info.

“In 2001, Comin-Anduix et al. evaluated the effect of increasing thiamine supplementation in multiples of the RDI on an Ehrlich ascites tumor-mouse model [58]. Their findings indicated a statistically significant stimulatory effect of thiamine supplementation on tumor growth compared to non-supplemented controls. Moderate doses of 12.5 to 37.5 times the RDI had the greatest stimulatory effect, peaking at approximately 250% greater tumor cell proliferation with 25 times the RDI. Interestingly, at values above 75 times the RDI, no change was found in tumor cell proliferation, and a slight decrease was found at 2,500 times the RDI. This observation suggests that there is a specific range in which thiamine supports proliferation. A recent study explored the relationship between a high-fat diet and thiamine levels on the tumor latency in the Tg(MMTVneu) spontaneous breast cancer-tumor mouse model [59]. In this study a normal-fat (NF) diet contained 10% of the calories from fat while the high-fat diet contained 60%. Low thiamine (LT) levels were defined as 2 mg of thiamine per 4,057 kcal and normal thiamine (NT) levels as 6 mg per 4,057 kcal. Tumor latency was significantly longer (295 days) in animals given a NF/LT diet compared with animals on NF/NT (225 days). Interestingly,the delay in tumor latency from LT was abolished when given a high-fat diet. This demonstrates an important interplay of dietary constituents on tumor progression that needs further characterization. Although more research is needed to confirm and evaluate the role of thiamine on disease progression, these studies have significant clinical implications. First, patients requiring thiamine to treat either chemotherapy or disease-associated deficiency should receive high-dose thiamine to avoid enhancing tumor growth. Second, self-supplementation of thiamine by cancer patients should be avoided as the low-to-moderate levels of thiamine may contribute to disease exacerbation.”

Issie, This is all super helpful info. Could you tell me where you got the instructions for the mouth taping for the apnea? I also have apnea -moderate central & some obstructive. If you could share a link to the mouth taping info, I’d appreciate it. And what mouth tape you use. I use Somnifix tape with ASV CPAP machine and low flow O2.

I’ve been taking B1& B2 200mg/day for about 18 mths since I read Cort’s 2013 article and decided it was worth a try. I’d been taking Benfotamine and then found out it doesn’t ross the blood/brain barrier. Within 2 days my CFS fatigue and PEM disappeared. In the last 6 months my food intolerances have progressed to borderline MCAS. I found out that NAC can decrease DAO so I stopped that and am taking lipo-glutathione instead. If B1 decreases DAO it looks like I’ll have to experiment decreasing the B1/B2 to 100mg/day and see what happens. That’s after I get my thyroid straightened out after a recall Walmart didn’t tell me about last summer. if it’s not one thing it’s something else, isn’t it? But we are making progress thanks to Cort and so many others research now. Hang in there everyone!

Genetically, I have genes that would decrease DAO. I also have severe MCAS, in the past. I have been on the protocol to reset/rebalance my histamine receptors. I no longer use antihistamines. Occasionally use mast cell stabilizers. But use a supplement to help balance my MCAS and watch my histamine causing foods. I’m better with that than I have been in years. Not over it, but better than I was on antihistamines, they really caused me issues with my brain. My brain is back and I can research again. Yayyyyyy! And I feel better! No more swings like when antihistamines wore off.

I don’t find that 100 mg B1 makes my MCAS worse nor do I find it causing my neuropathy to be worse. But I do have more muscle strength with it and it seems more ups than downs. I do take it in mornings as it does seem to increase energy.

Also having tried a real good trial of Diamox and knowing how that made me feel in my head and my body……I can say that B1 does NOT give me the same feeling that the drug did. I don’t feel that same effect. Soooooo, ??????? Not sure if thats the mechanism of the benefit.

Can you share more about the “protocol to reset/rebalance my histamine receptors” or a link to more info? Thanks!

We have some threads on Healthrising Forum that links a book i read that is very technical. (One of the hardest I’ve read as it explains deep science of the histamine receptors and how they work.) It made sense to me. And I started trying things. I will say, as I don’t think I’ve updated what I’m using there, that I find Nettle tea and a Bee Propolis/pollen/ royal jelly to be my best helps for MCAS. Along with watching histamine causing foods or foods that I’m sensitive to which include high oxylate, lectin and nightshade foods. Dejurgen and I have written many times on histamine and its benefits. And why it is needed and not to be completely suppressed. You can search his name or my name and probably pull up some post under histamine. And then I know there is the one by Bayard on the Forum. (And where the book link is.) But Dejurgen and I have one too, but we haven’t updated it.

Thanks, Issie!

Thanks Issie! Could you share what the supplement is that you are using for mcas? Is it the bee propolis, etc stuff you mentioned below, or something else? Thank you 🙂

@mj, yes the bee stuff, nettle tea and being careful with diet. The one other diet thing I forgot to mention was I try to do no gluten.

Glad to hear thiamine has been helpful! The relationship of thiamine to mast cell issues, if any, is one area that is really not clear to me. My daughter’s MCAS has not gotten worse with high-dose thiamine, though her food tolerances have shifted around a bit. But the MCAS has not gone away as I had hoped it might. I would imagine there could be many different explanations for food intolerances getting better or worse. Certainly supplements / medications can play a role, but many people take multiple supplements / medications, so it can be hard to isolate which one is having an effect. Hope you figure out an approach that works!

We are so, so sensitive to supplements and medicines. We can use so much less than what may even be considered a “normal” dose. If people realized how few of something it takes to trigger a response, they would be surprised. Dejurgen always says, look how small an amount of pollen it takes to trigger us having allergies. Or how small an amount of gluten to trigger celiac, even a small dusting can trigger it. Since we are sooooooo sensitive, more is NOT better. More can imbalance us even MORE. Soooooo, lower and slower. Paying close attention to response and no fast adjustments.

He is Soooooooo Right on that one.

Low-Dose Naltrexone 4.5mg has helped my food intolerances & MCAS dramatically. As did starting (refrigerated) Creons for severe digestive/absorption issues, which was the first step. Then LDN seemed the cherry on top. If she hasn’t tried LDN already – and I mean, a good 6-12months stint as it took me that long to see improvements- I would highly recommend it.

Also, I am sorry to hear of your daughters health struggles, especially so young. My ME/CFS started at 18 and I am now 36 so my heart breaks for her. I so hope cures will be found in her lifetime!!

And commend you for fighting for her, your support will make a world of difference to her life.

Hi T Allen,

Thanks for the share. Can you please tell me what DAO is? And you have learned that NAC decreases it but not lipo-glutathione? (I currently take NAC and am about to start liposomal glutathione). Are you saying that B1 also depletes DAO? What the heck is DAO?

Thanks!

Kate

I also found this on B1:

“B1 is necessary for the production of hydrochloric acid, for proper digestion.”

Throughout my 26 years with ME/CFS

adequate digestion has been a problem, leading to malabsorption, etc. I must now take Betaine HCL to digest meals properly.

Interesting. thanks!

Hi I was taking 1000mg pd for approx 2 years after reading the small study and desperate to recover. I only stopped it recently because I feel ok with my multivits and celery juice regime. I no longer nap during the day unless bored or I relapse. I work part time and recently started doing 10 mins yoga sessions and I have an 8 year old to care for as a single mum. I recharge one day a week when he visits his dad but even when he is home I can manage. I still have me/cfs and I cannot do anything that increases my heart rate to much such as exercise or stress or the PEM comes. I will use B1 again if I notice my energy levels dipping because I believe it made all the difference to me. Off topic in case anyone is interested I had the Oxford vaccine with no side effects and I’d been so stressed over it!

Thanks for sharing your experience. If you are comfortable completing the survey, would be great to capture your experience.

Interesting timing. I’ve been taking this for the last few weeks. I didn’t think 200 mg was considered to be high dose, but since it qualifies I’ll take the survey.

I experienced some complications which probably won’t fit there (my apologies for the length!), but might be relevant for some of you. I’ll post here so hopefully you can learn from me before going through anything similar yourselves!

Oxalates, and oxalate dumping, and MCAS have all complicated the picture for me. I’ve experienced a strong paradox reaction – that Drs. Lonsdale and Marrs warn about – but which tells me something about B1 is on target. I take heart from their posts that the paradox reaction is a sign that things can get better.

Significantly – for the first time since I got my period several decades ago – I’m, ahem, … regular! That’s something, let me tell you!

A number of weeks ago I happened to come across a number of articles on B1, all in a short period (which at first I didn’t register as relevant to me), including:

Mercola: Ominous B1 Deficiency Found Throughout Food Chain: https://articles.mercola.com/sites/articles/archive/2021/02/08/deficiency-of-thiamine-vitamin-b1.aspx

The Ocean’s Mysterious Vitamin Deficiency: https://www.hakaimagazine.com/features/the-oceans-mysterious-vitamin-deficiency/

Thiamine deficiency in diabetes mellitus and the impact of thiamine replacement on glucose metabolism and vascular disease: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1742-1241.2011.02680.x

But it wasn’t until I got a notice for this article that everything started to come together:

SIBO, IBS, and Constipation: Unrecognized Thiamine Deficiency? https://www.hormonesmatter.com/sibo-ibs-constipation-thiamine-deficiency/

I was in a particularly bad crash at that point because of pretty strong oxalate dumping (having recently gone very low oxalate without understanding the risks) – which included a lot of pain, acidity, and a complete cessation of gut motility no matter what I tried. So the HormonesMatter article was a ray of hope. The Mercola and Hakai articles had registered somewhere, and once I put all of that together I sent my husband out to get thiamine. He got the advice that benfotiamine(sp?) was the best absorbed, so I started on that. Considering my history, I opened the capsule and took about 1/3rd.

The Good:

Holy Moly. INSTANT MOTILITY! And a feeling I could really breathe, for the first time in months (perhaps years). And I started feeling like one of the patients from the movie “Awakenings” after their first dopamine treatment. Energy, and a drive to want to do things. Why had no-one ever suggested this before?

The Bad:

But that was quickly followed by a whole mess of negative symptoms that grew over the three or four days I tried it – growing severe pain, extreme acidity, horrible gas, emotional lability (my poor husband 🙁 !), sympathetic system on overdrive (even more than usual), feeling buzzed and unable to sleep. And more ugly stuff I’m sure you don’t need to hear. Worst of all (I now realize, but didn’t notice how badly until yesterday) my hair started falling out. Severely. So fair warning to all. Not sure that last bit is exactly the fault of thiamine, but that’s when it started.

Eventually I found my way to Cort’s 2013 articles and survey (thank you Cort!). And read a few more articles on the HormonesMatter blog – including the concept of paradox reaction, which I clearly had. So I sent my poor hubby out again, this time for thiamine HCL. That made a huge difference – much more tolerable. I worked my way up to 200 mg, but that aggravated things after a while. So I have just this morning backed down again after reading more about the paradox reaction.

Once on the thiamineHCL the worst things died down, but haven’t gone away completely. Except – my flushing and histamine attacks got MUCH worse, whereas I hadn’t noticed that with the benfotiamine.

I can’t know for sure, but it seems the thiamine (both kinds) accelerated the oxalate dumping, which caused the worst of the symptoms – including through the roof acidity. Since the wonderfully increased motility has kept up (yah!) I assume my body has taken that as a signal to keep dumping oxalates. Aside from switching to regular B1 (HCL), I’ve found some things which seem to have helped that considerably, and also seem to have helped the histamine reaction:

1) I had a very (delicious!) high oxalate meal, which is known to break oxalate dumps for some people.

2) magnesium oxide, alongside my usual magnesium citrate, is highly alkalinizing and that helped immediately;

3) evian water is one of the lowest acidity waters (much better than our city tap water – despite the fact we filter it) and seems to be helping quite a bit as well. Hubby has just gone out to look for some alkaline water to see if that does anything.

4) taking the B1 very early in the day helped with the WIDE-AWAKE-INSOMNIA (still there, but much better), and

5) taking it together with magnesium oxide, quercitin, potassium and vitamin C seems to have also helped damp down any histamine reactions (still there, but brief and much weaker).

So, overall my motility now is a thing of magic(!), I have more energy (not huge, but there), and feel like I can breathe easier. (But not anywhere near as well as the first day).

The scary thing is the pretty extreme hair loss (in just a couple of weeks), which is probably due to oxalate dumping, but is known to be caused by low B7. So I’ve sent my husband out to get some biotin (b7) and alkaline water. Hoping to heavens that works.

My apologies for the long essay. Still trying to put all this together, and didn’t think most of this would fit on the survey (or make much sense), and wanted to give people a heads up to the possible downsides.

Sorry – brain fog strikes again. Jeffrey was commenting on the vaccine survey in the comment above – somehow I interpreted that to mean that Cort was doing another B1 survey!

You might be right on about needing the biotin. The Thiamine supps may be competing with it. Might consider taking the Biotin away from the Thiamine?

That too fast oxylate dump….ugh! I’m sooooo glad you warned of it. I knew to slow that down when I went lower oxylate. It was a BIG thing that has seemed to help with me, getting oxylate diet lower. And is NOT to be done in a quick way or there is some really nasty side effects.

As for hair loss, I have a friend in the business of hair restoration and she says that we have hair turn loose 3 weeks before it starts to visibly shed. So think back 3 weeks ago and see what changed. It could had been an emotional upset even.

I too found that the regular form of B1 was the most effective for me too. I took bottles of Benforthimine and didn’t see benefit, years ago. But B1 HCL does make a difference.

Low and slow when changing diet to low oxylate.

” And a feeling I could really breathe, for the first time in months (perhaps years). And I started feeling like one of the patients from the movie “Awakenings” after their first dopamine treatment. Energy, and a drive to want to do things. Why had no-one ever suggested this before?”

Especially with the “a feeling I could really breathe, for the first time in months (perhaps years)” I suspect a lot of the symptoms could be related to a former years to decade long situation of hypo perfusion (hypo oxygenation) in many many parts of your body being reversed far too quick.

That could IMO create something *resembling* reperfusion injury in many of those areas. The damage (and inflammation) of reperfusion injury after hypoxia / ischemia is often said by doctors to be worse then the damage (and inflammation) of hypoxia itself.

If that would be the case, you might going WAY too fast to such high doses. *IF* your body would have adapted too and found workarounds for plain surviving in very low oxygen supply situations for decades, you can’t expect it to do well when you flood it at once with oxygen again.

Compare it to having a house with all doors and windows closed and with a smoldering fire and plenty dark smoke in it. Open all doors at once and many chances you have either a ball of fire hurled your way or at least flames flaring up massively.

Just like that flaring flame isn’t a sign everything will be better soon, the same thing could be said for that (if present) reperfusion injury inflammation.

I use another trick that improves my breathing a lot. It took quite a bit of puzzling to get it start working without backfiring and the patience to grow from ridiculous small amounts of supplement to still far smaller then what the label says a year later.

Issie, who has more genetics issues then I do, isn’t able to get it working even after two years and her being utmost sensitive and able to get unlikely things working. The trickyness of this one with the big potential to backfire is why we don’t share this one. But for me: going loooow and sloooow helped me so much.

With 500x daily recommended dose this strategy might seem impossible, but for example starting 1x, 5x, 10x, 20x,… at 1 step per month will get you there in less then a year too with the potential for underlying inflammation being cleaned up by given the right doses of extra oxygen needed for optimal repair rather then being flooded by it at once.

Thanks for sharing both your positive and negative experiences. If you feel comfortable completing the survey on high-dose thiamine, it would be helpful to be able to include your experience. Your remarks here are also helpful for expanding on your experience. Thanks for considering. https://forms.gle/y2ZV8yqk3wUw9rph6

Jeffrey:

Thank you for your article, and for doing this. I hope all of this will prove helpful for your daughter – and the many people who share her conditions. Thank you from all of us!

So there is a survey! My brain has been especially addled lately, so thanks for clearing that up. It may take me a day or so to respond; I’d prefer to wait for a time my brain is clearer so I don’t ramble as I did yesterday.

Issie:

Thank you for the comments re: reducing oxalate slowly, and the hair information! Three weeks prior would have been exactly when I started the benfotiamine; I can date it exactly because of the HormonesMatter article. I started it on March 17th. I attended a birthday party on April 2nd (family) and in those photos there is no hair loss yet (at least not visible, and I hadn’t noticed hair falling out at that point). Does your friend hold out any hope for whether or not it will regrow once the ‘shock condition’ is removed? (I may not want to know the answer if it’s bad.) What’s become obvious now that I can clearly see my scalp is how consistently crimson my scalp is. Perhaps that inflammation dejurgen was mentioning? Oddly, my face only periodically flushes, but it seems my scalp is on permanent flush?

It seems you and I may have very similar issues going on! I know that I need to take much less than the standard dose of anything (or much much more sometimes – hard to know beforehand). I’m a bit shocked that 1/3 of the pill over three or four days would do that much (but shouldn’t have been, in retrospect).

Would you happen to know of any good articles on dumping – specifically what the harms/risks are? I see lots of warnings, but none with any specifics, especially no details of what harms are likely/possible, and aside from the extreme discomfort what actual physical harms are occurring, nor what the actual danger might be.

Because of so much brain fog I find all of this both confusing and exhausting. There seem to be quite a few people writing about oxalates, and thiamine, etc… but – from my perspective – it seems they’ve all forgotten how their brains worked in the midst of their disease states. Or perhaps they’re all still in that state a bit? So I’m finding it’s too easy to miss important details and considerations, and even sometimes the overall picture. I wish someone would spell out the overall picture and the most important things in point form so I know what’s important to attend to.

Cort:

Which reminds me – thank you Cort for including ‘The Gist’ in your articles. That’s SO helpful when my brain isn’t working. I wish more people would do that when they’re writing for people with cognition issues.

dejurgen:

Thank you for your detailed explanation, and especially the very clear cautions about reperfusion injury! I’ll certainly take that on board. So the movie I should have been referencing was ‘Backdraft’? 🙂

I wasn’t clear on exactly what it was that worked for you but not Issie re: improving your breathing. Was it that you were able to start out at a very low dose of B1 and slowly increase to a high dose, but that Issie needed to remain at a low dose? It sounds like Issie and I have many of the same challenges, so if so that is good information. If I’ve misunderstood, would you mind explaining a bit more?

Thank you all!

@Anne:

“I can clearly see my scalp is how consistently crimson my scalp is.”

I’m not a native English speaker, so I miss the subtle definition of what color is exactly described by crimson.

If it’s red without any blue, black or brown-ish hue, then there is a good chance it points to rather good blood flow with a possible touch of inflammation. If your hair falls out, their might be more inflammation going on then you desire. With good blood flow, lack of blood flow won’t be the likely cause of hair loss.

As the scalp is one of the places where blood reaches slower to, it sort of would suggest that much of your skin everywhere should be well fed with blood and full of color if it where just that. As you say your face only flushes periodically, it could well be that you have an MCAS / allergic reaction going on on your scalp. Is it rather itchy?

The thing that helps me with better breathing isn’t B1. It’s an OTC thing that IMO has quite a bit more punch then B1 in select cases and that includes quite a bit more potential to fire back dangerously strong. We both experienced it. We will disclose that one later but only with massive warnings, more to show what mechanisms it seems to modify with us.

@Anne, do you have alopecia and hair coming out in clumps or is it more of a shedding? Alopecia is considered somewhat autoimmune and that is unpredictable as to whether it comes back or not. I have it occasionally and when I lost one large clump, Mayo doc gave steroid injections into the spot to stop the autoimmune attack. It did come back, but I also have vitiligo (lack of melanin/color pigment) and it came back in a most beautiful silver. And now with some additional silvers coming in, my hair looks beautiful streaked. I wanted more of them put in, but the beautician didn’t think she could match the color well enough. Told me to give it time and it would happen on its own. LOL. I embrace it. I like it. I’m mostly an ash dark blonde with these beautiful silver streaks. But I also have had excessive shedding of my hair too. I think that is stress related and just generally being in a Chronic health state. That is unpredictable as to whether it comes back in too.