The question must have rattled through everyone’s mind at some point. Why me and not you? Why did you get over that cold while I never did? It’s one of the great questions in the chronic fatigue syndrome (field).

Jason has blood samples from before people came down with ME/CFS.

Stabs have been taken at it before – but not many. Studies which assessed psychological comorbidities, for instance, attempted to see if there was a psychological predisposition to getting ME/CFS. (There wasn’t).

The Gist

- Leonard Jason has blood samples from before college students came down with infectious mononucleosis (IM) and afterwards. He’s following them to see who comes down with ME/CFS.

- He’s been using those blood samples to see if he can spot an immune hole which was present when the students were healthy which put them at risk for ME/CFS.

- Jason’s last study suggested that low levels of three cytokines (IL-5, 6 and 13) might be putting college students at risk of getting ME/CFS if they come down with infectious mononucleosis.

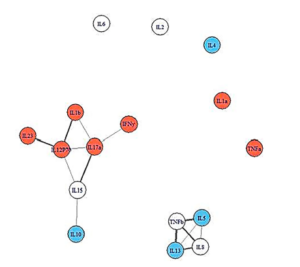

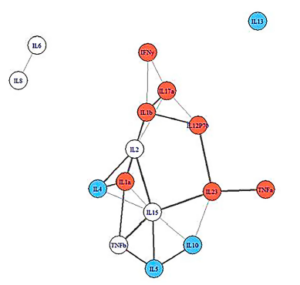

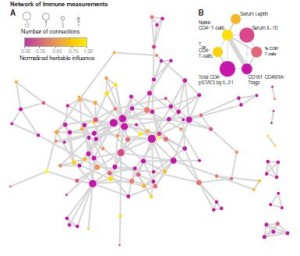

- In this study Jason et. al. did a more powerful analysis of the networks cytokines are embedded in. Cytokine networks are believed to more reflect disease processes than assessing the levels of individual cytokines.

- This study found that the college students who failed to recover from infectious mononucleosis had more restricted, inflexible cytokine networks while those who were able to recover from it had more flexible, less interconnected networks.

- It was as if the cytokine networks of the students who failed to recover didn’t have as many options or opportunities for action as the students who did.

- A prior study using the same kind of network analysis came to a similar conclusion. For whatever reason the ME/CFS patients immune systems were kind of already “locked in”.

- The study also found less involvement of an immune network designed to fight off pathogens in the students who failed to recover from IM.

- In further studies Jason hopes to be able to build a model which predicts who is likely to come down with ME/CFS after an infection.

- Jason, I believe, also has blood samples from college students before and after they came down with long COVID.

No one, though, to my knowledge, has what Leonard Jason has. Jason has blood samples from before college students came down with infectious mononucleosis (IM) and afterwards.

That means he can compare baseline status of those who failed to recover from infectious mononucleosis and came down with ME/CFS – with those who were able to recover from IM. Jason, then, can at least take a swing at the question – why did I get sick while you didn’t.

The Study

Jason has already found that college students with reductions in several cytokines (IL-5, IL-6, and IL-13) were more likely to come down with ME/CFS after IM. His new cytokine network analysis paper, “Cytokine networks analysis uncovers further

differences between those who develop myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome following infectious mononucleosis”, presents something arguably more important.

Because cytokines operate in complex, multidimensional networks, the functioning of a network is always more impactful than the functioning of a single cytokine. If you find out that a network devoted to fighting off pathogens has gone wonky – that gives you more does information than does the reduced levels of a cytokine or two.

Plus, the data on cytokines in ME/CFS has been mostly inconsistent – making it difficult to pin down what, if anything, is going on.

Jason’s network analysis found that the low levels of IL-6 found in the former study didn’t seem to matter much to the networks in which IL-6 was embedded. That authors pointed out that because “The ability of IL6 to influence other cytokines” did not differ amongst those who recovered and those who didn’t, IL-6 was probably ‘less of a critical predisposing immune irregularity leading to ME/CFS‘”.

That’s an important finding. Il-6 is believed to be a major player in many inflammatory and autoimmune diseases. If this study is correct, though, it’s probably not a major factor in post-infectious ME/CFS.

The two other cytokines with low levels (IL-5, IL-13) were, on the other hand, associated with disturbed immune networks in the students who failed to recover. They present the possibility of a double whammy: not only are their levels low, but they’re operating within a possibly dysfunctional network.

Flexible vs Rigid Cytokine Networks

People who recovered from infectious mononucleosis had more open cytokine networks.

People with more severe illness had pinched, more constricted cytokine networks.

The network analysis showed an intriguing and promising pattern. People who recovered from IM had broader, more loosely linked networks. People who came down with ME/CFS, but were less ill, had denser, more closely packed immune networks, while people who became more ill displayed the smallest, most densely connected immune networks. This was all prior to becoming ill.

A 2010 network analysis found a similar pattern. People with ME/CFS are on the right.

It was as if the ME/CFS patients’ immune systems didn’t have the breadth or suppleness needed to cope successfully with EBV.

Instead, they appeared to be locked into a more limited immune response. The wider range of resources available to those with looser and broader immune networks may have helped them fight off IM and recover.

This isn’t the first study to suggest that congested and inflexible immune networks are present in ME/CFS. A 2010 cytokine network analysis found a similar pattern.

A great question, of course, is how a healthy person gets their immune system shifted like that? A prior infection or traumatic event could have done it.

Studies indicate, for instance, that prior cytomegalovirus infections dramatically impact cytokine networks.

Smoking Gun Found?

The missing immune links in the soon-to-be ME/CFS patient seemed apropos indeed. Both the ME/CFS and the severe ME/CFS group displayed a “lack of involvement” in networks associated with interferon-gamma (IFN-y) – a key player in the antiviral response.

IFN-y has been called “critical for innate and adaptive immunity against viral, some bacterial and protozoan infections” and aberrant IFN-y responses have been associated with a number of autoimmune and inflammatory diseases. Not only does IFN-y directly inhibit viral replication, but it has also immuno-stimulatory and immunomodulatory effects. Interestingly, it’s mostly produced by two problematic immune cells in ME/CFS: natural killer and natural killer T-cells.

The finding suggests that the immune systems of people who later came down with ME/CFS may have had trouble fighting off the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV). Jason’s studies are the first to possibly identify an immune hole that existed prior to becoming ill, but they aren’t the first to suggest people with ME/CFS have trouble with EBV.

Has Jason uncovered an immune hole which allowed pathogens like EBV to take root?

In 2014, Loebel found a “deficient EBV-specific B- and T-cell memory response in CFS patients”, which suggested people with ME/CFS might have trouble controlling EBV. Another study suggested that one part of the immune system in ME/CFS may be responding more actively than usual to an EBV protein. (Overactivation is as bad as underactivation.)

EBV may also be hyperactivating a “critical” gene in the immune and central nervous system in a subset of patients. A smoldering EBV infection also appears to be producing an enzyme that is sending the immune systems of some people with ME/CFS into a tizzy.

Plenty of options, then, exist, which could explain why people with ME/CFS might have trouble with EBV. One wonders, though, if Jason might have identified a key one – an essential difficulty engaging parts of the immune system to fight off EBV in the first place.

Jason et al. readily admitted that the cytokine studies in ME/CFS have produced mostly inconsistent, even contradictory results but argued that cytokine network analyses are more likely “to drive disease processes”.

Next Steps

Nancy Klimas made a similar point in talk to long-COVID patients in a Body Politic webinar. Because ME/CFS is a whole system disease, she believes that whatever explains it is going to have to show – from the cellular level to the whole body – how this disease has evolved. In other words one finding is not going to do it. It’s going to take multiple findings that get pieced together to understand ME/CFS.

This study, then, is just one potential step on that process. Jason also has blood samples from pre-COVID college students, as well. As the keeper of these precious blood samples, Jason, if he has the funds, could conceivably uncover the immune and other holes present before the illness, as well as what happens as these illnesses progress over time.

Possibly cytokines are being targeted in ME/CFS like they are in Long Covid as the study below suggests autoantibodies to cytokines themselves in Long Covid were found. Also Autoantibodies to beta-adrenergic and muscarinic cholinergic receptors

Interestingly the autoantibodies seem to be targeting immunomodulatory proteins including cytokines, chemokines, which will be free floating in the blood (“Something in the blood“)

Cytokines being attacked fits Dr Nancy Klimas work showing that ME/CFS sufferers cytokine communication systems was broken, i.e. lots of activity, yet no communication. So this Yale study would fit if certain cytokines were meant to be communicating, but instead autoantibodies are interfering.

Interestingly this Long Covid study also found cell surface proteins are possibly being targeted too.

—————-

Diverse Functional Autoantibodies in Patients with COVID-19 | medRxiv

https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.12.10.20247205v4

—————-

What’s Intriguing is when looked for the same autoantibodies for beta-adrenergic and muscarinic cholinergic receptors were found in a subgroup of ME/CFS patients.

The only reason there hasn’t been cytokine autoantibodies found in ME/CFS is because no one (to my knowledge) has looked for them. Funding again to blame

——-

‘Autoantibodies to beta-adrenergic and muscarinic cholinergic receptors in Myalgic Encephalomyelitis (ME) patients – A validation study in plasma and cerebrospinal fluid from two Swedish cohorts – ScienceDirect’

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2666354620300727

——-

Would there be any value, then, in treating a subset of ME/CFS/FM patients with interferon, to see if the body can mount a proper defense now?

Antivirals/immune booster can help some but I don’t think there’s much evidence indication that EBV reactivation is causing ME/CFS.

It may be more likely that EBV did something during the infection which is causing ME/CFS – initiated an ongoing autoimmune/inflammatory response. It’s also possible that smoldering EBV infections are producing a protein which is tweaking ME/CFS patient’s immune system but I don’t know if interferon would help with that.

Interferon is used here in LA for CFS/ME.

It has been used but very rarely. There is a recovery story from someone who used IFN-a on Health Rising – https://www.healthrising.org/forums/resources/low-dose-ifn-a-works-for-linda.31/.

Different form of interferon are used to treat hepatitis. One issue with interferon is that in a subset of patients it actually causes ME/CFS or something very similar to it. – https://www.everydayhealth.com/hepatitis/treating-hepatitis-with-interferon.aspx

Wow! Great study. Fingers crossed this goes somewhere.

I received a 3 month course of Interferon @ the Royal Free hospital in London in 1996 (this was 8 years after I contracted ME in 1988)

The only result I had was severe fatigue,, aches,, flu -like symptoms,,, depression,, etc for 3 months.

So I don’t think it helped me at all..

Though saying that,,,, I did feel a relief after coming off the drug.!!!!

No real surprise. If its the right drug for you – if it helps someone fight off a pathogen then great.

\

Even then it kicks the you know what of a substantial number of people – which is worth if it helps get rid of the pathogen.

We have certain genes that can predispose us to different responses with TH1 and TH2 and cytokines. Looking closer into that may be a possible way to also tell those differences. And explain more of our WHYS for ongoing inflammation and WHY the immune system isn’t detecting the cause and eliminating what could be causing it in the first place. (One of my long held hypothesis, Autoimmune Dysfunction and Inflammation…..pick your order.) I think genetics is a big part of the puzzle. And then wonky response of certain pathways. There are ways to tweak it. But it will be an individual journey.

I recommend Selfhacked if someone has their genes from 23&me and do a search on the different cytokines in the look up section. You can see how your genes affect you there and what to do about it. Of course don’t do all of it. Try one thing and see if there is improvement.

Also Debbie Moons site, Genetic Lifehacks. She has written some blogs on cytokines and connected different genes to her blogs.

Both of these sites you have to be members of. But they have both been helpful resources.

Interesting about the Cytomegalovirus producing a huge immune network shift. When i was first diagnosed with CFS back in 1993 my immunologist found that i had had CMV, EBV and RRV in the past, though i never knew at the time. All i remember is that i felt really ill but just thought it was a flu. He said no wonder i have CFS! Also said i would recover in 12 months….it’s now been 28 years 🙂

Hi Jo,

My daughter too showed up CMV in her bloods after she came down with what has now been 12 years of ME/CFS. And she is only 25!

She also had Roseola as a child…HHV6..

the paragraph in the article is

“Studies indicate, for instance, that prior cytomegalovirus infections dramatically impact cytokine networks.”

My question is…..impact can be good or bad….i am assuming its a negative but logically an experience for your immune system should ideally improve its performance for the next event so not sure….!

yes, i had similar experience, except i have FM.

Dysbiosis is said to be the cause of cytokine dysregulation. Unfortunately the knowledge about our microbiome is still rudimentary!

The more we find out about the microbiome the more we realize how powerful it is. I wouldn’t be too surprised if many chronic diseases have a source in or at least are contributed to by the microbiome.

Interesting.

A big question remains however: are the cells no longer able to produce the correct amounts of cytokines, or no longer willing?

(For ease of thought I leave possible destruction of produced cytokines to Brendan Rob’s separate antibody ideas.)

If the cells would be no longer able to produce the right amount of cytokines, then chemically stimulating (or inhibiting in the case of overproduction) cytokine production might offer opportunities. That already would be rather challenging as not every part of our body needs the same amount of cytokines 24/7 in order to work optimally.

If our bodies would be no longer willing to produce the “right” (with “right” meaning here same as healthy people) amounts of cytokines, it might be by *choice* in order to try and work as good as possible in the given situation.

For example, for a healthy person, a bit less or more inflammation is a reasonable option if new circumstances ask for it. For a “seemingly healthy” / “healthy but prone” person with an underlying specific defect in mucus production like research showed about one third of ME patients have, changing (certain aspects of) inflammation up or down even a bit might create long lasting and hard to repair damage on the mucosal barriers throughout the body.

If so (in this hypothetical situation), some “typical” and beneficial immune response that a healthy person could mount against a new pathogen might be as good as “off limits” for a prone person with such genetic mutation on his mucosa. Such person would have a far more restricted option of immune responses available to any threat.

That would require the body to make stronger use of the tools it still has at its disposal, making the “forbidden” immune response clearly less strong and the remaining available immune responses needing to be a lot stronger to make up for the deficiency in the “forbidden” part compared to healthy people.

In that idea, part of the immune response in prone people when getting struck with ME would be under powered, and others over powered. All of that is resembling the truncated cytokine networks in students that would later come down with ME:

Some cytokines are “cut away” from the cytokine networks. Basically, they are unable (?not allowed?) to influence the rest of the immune system much and hence sort of make sit part of a normal immune reaction sit idle. Other parts form smaller more dense networks. Smaller networks mean less diverse interaction so less variety of immune reactions is possible (/ allowed?). And those networks are “tighter”. I try and understand that as: those fewer and remaining interactions between cytokines are stronger. That is close to the idea that what options the immune system still has left “need to be over used”.

That would leave the immune system unbalanced. That leaves us with something resembling what we typically see with both auto-immune (and auto-inflammatory) diseases and ME: parts of the immune system are under powered, parts of it are chronically over activated.

On top of that, a strong infection is a harsh thing to the body. The body first mounts a strong chemical attack to large parts of the body, then has to find ways to repair the large collateral damage this attack has done to the body itself. Compare the response of the body to showering the body with a large amount of different chemo therapeutics all at once. That will and does create damage that needs plenty of coordinated action to clean the mess up and restore body function.

When some parts of the immune system are “forbidden” / crippled, others have to work in over drive. More damage to the body is done. Compare that to the need to use higher doses of dangerous chemicals in cancer therapy. After the infection is cleared, a balanced immune response is needed to clear the damage as well as possible.

Yes, I say a (balanced ) *immune response* is needed to heal and repair the body after the combo of damage made by infection and chemical warfare the body waged against the infection. Remember: inflammation is both an immune process and ?almost exclusively? a (n attempt to) healing process at the same time.

So I think: if immune processes are limited and unbalanced, then chances for recovery by a correctly balanced healing inflammatory process will be equally crippled.

Restoring such problem is likely rather challenging. Trying to spot individual weaknesses preventing the immune system to mount a more balanced immune response and correcting those might be the best way to go there.

“I try and understand that as: those fewer and remaining interactions between cytokines are stronger. ”

That’s how I thought of it.

The idea of an over compensation causing problems makes sense to. I assume that the very complex and diverse immune system has developed many ways to compensate for deficiencies – leading to some parts being over activated and some underactivated – a real detective problem as you note. It’s even worsened by the fact that as Mark Davis at Stanford said – we don’t really know what a normal immune system looks like.

Thinking of it: cytokines are produced by many other cells then immune cells.

For example Wikipedia(Interleukin_8)

“Interleukin 8 (IL-8 or chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 8, CXCL8) is a chemokine produced by macrophages and other cell types such as epithelial cells, airway smooth muscle cells[3] and endothelial cells. Endothelial cells store IL-8 in their storage vesicles”

Epithelial cells produce plenty of it and even hold a private “stash” in their sorage veshicles for quick use.

So, epithelial cells can stear the immune system, make requests for immune activation. They sort of can signal “an attacker is here, immune assistance needed”. That makes sense when a pathogen attacks them, or when a “rogue protein” hinders their correct functionning (like for example gluten / gliadin).

But what if they didn’t use this option only for defence against pathogens / troublesome chemicals, but for the immunes systems *repair function* (aka inflammation)? What if the cells were designed to be able and willing to invate the immune cells to help them repair and heal trough the means of inflammation???

“IL-8, also known as neutrophil chemotactic factor, has two primary functions…

Interleukin-8 is a key mediator associated with inflammation where it plays a key role in neutrophil recruitment and neutrophil degranulation… Interleukin-8 secretion is increased by oxidant stress, which thereby cause the recruitment of inflammatory cells and induces a further increase in oxidant stress mediators, making it a key parameter in localized inflammation.”

So it does seem to do more then just invite the immune system to remove pathogens… … ???repair functions aka inflammation???

If so, that could combine with Naviaux’s Dauer hypothesis pretty well.

Naviaux hypothised ME patients cell go into a “Dauer like state”, sort of turning down and trying to survive long time until a certain threat is over. It was named after a certain worm being able to live and survive way longer by “inhibiting” for a long time if the environmental conditions were harsh and “coming back to live” when the threat is over.

He also noted that in this Dauer state our cells turn into a defensive position, where our mitochondria scale down producing ATP for activities and stear energy production towards the production of hydrogen peroxide in order to defend themselves and the cells against “a certain perceived danger”.

One difference with the Dauer state of the worms is that we don’t truely hibernate, and even our cells and mitochondria don’t truely hibernate. Producing copious amounts of hydrogen peroxide (oxidative stress) is a process consuming quite a bit of energy. So we don’t truely hunker down to save energy as our environment lack food.

That is sort of a split in views on ME too. Some researchers see ME as a hypo-energy disease, some see it as a hyper-energy disease. That is cellular usage, not the ability to do activities of coarse. That is also seen in some of the most severe ME patients: despite optimal tube feeding people like Withney Dafoe are skinny and severely underweight. Other very severe patients report very low weight while having very high calloric intake. Part can be attributed to poor nutrient uptake, but that IMO only tells part of the story.

WHAT IF:

The primmary task of each individual cell was to keep itself in good health first and contributing useful activity to the organ and body as a whole second? Self preservation is pervasive in biology after all.

Then the first task of the cells would be to go into this “defensive mode” producing few ATP but plenty of oxidative stress. This wouldn’t be the “wrong” diseased state as suggested in the Dauer theory but the fundamental mode of the cells: defend and repair onself first and above all!

Then, when the state of the cell is healthy and only when it is so produce ATP and perform a useful function contributing to the organ and body as a whole.

Weird as this idea may sound, it has some strong points going for it:

A cell having worked hard or long on useful activities will have spent less time on it’s first and basic task: to defend and repair itself. So, after both more intense and longer work, a cell will have largely forgone on sufficiently defending and repairing itself. Then it would be only logical to have to do the following:

* Reduce ATP production and useful activities drastically after a too intense too long activity. The reduction would have to be far more severe if the cell wasn’t healthy to start with.

* Produce plenty of oxidative stress to try and defend the cell against pathogens that might have taken advantage of the cell “letting its defensive guard down” during the activities.

* Let the mitochondria go through the process of fision and fusion to clear out potential mutations in their DNA while they didn’t defend themselves enough against toxic (to DNA) chemicals.

* AND… invite the inflammatory (aka repairing) part of the immune system to lend them a hand.

Now isn’t that near *exactly* what the muscle cells do after a strong workout in healthy people? Research has described the inflammatory process after (proportional, so not too light not too heavy) exercise as being healthy and strengthening the muscles and body (aka the inflammatory reaction is repairing and healing and even strengthening).

Isn’t that also what happens with us after even very modest exercise and mental activity? Use our brains too much and they start to hurt and become very slow and fogged, and soon after it pain and weakness expands througout the body to limbs and gut. Our noses get stuffed and often our eyes dry and showing clear red blooded veins in the white. That are all signs of inflammatory reaction.

So: if the cells are in bad shape, maybe even a little amount of activity results in the cells sending out calls for help with urgently needed defense and repairs to the immune system.

When immune networks are short and trunkated and immune cells exhausted, the immune system has few options available. For all repairs it does, half of them will need future work “and another new repair crew later” to undo the things they broke while trying to repair stuff.

Compare it to having only few and exhausted repair crews avialable for repairing your broken central heating system. Worse, most small crews have only a few basic tools: a hammer, a saw and a drill. If your heating system is in a dire state, you’ll invite them. And you’ll invite another three crews after them to undo the damage done during their repair until the central heating is up and running a bit again. You’ll also try and reduce usage of your central heating system as much as possible in the hope it wont break as quickly and try and do as much as possible basic repairs and workarounds yourself.

That has plenty of similarities of what seems to be going on with our ME body and cells. The cells and mitochondria have to spend a disproportional amount of time in their “defence and inhibit” state versus the “produce ATP and do something usefull state” AS repair services of the inflammatory / repairing part of the immune system are hampered by broken immune options, networks and functions. Repair is less effective and leaves more collateral damage, again offloading more repair work to the cells and mitochondria. As repairs are of lower quality, cellular damage and need for repair piles up.

As immune cells are cells too and have mitochondria too, they too are prone to this dire state and need to turn to a self-repair and defense state more rather then turning to provide useful services including repair services to other cells and organs.

When cells body wide have to turn more of their time and energy towards self defence and repair, waste removal like toxins removal by the liver or removal of plaque in veins gets the back seat too making running cells and the immune system efficiently even more difficult. It’s fairly easy to see ourselfs getting caught in a vicious circle by all of this.

=> WHAT IF this is the missing link, the forgotten part:

* The first duty of the cells is to defend and repair themselves BEFORE providing usefull activity to the organ and body (that is the function of the healthy cells that can spare the effort).

* The repair part of the immune system is hugely overlooked and cells use that and need that on a daily basis.

* A defective immune response not only means a less optimal response to pathogens, but ALSO a crippled ability to repair. That is bad on a daily basis AND after clearing out a pathogen left plenty of colateral damage in need for repairs.

The later would also unite the gradual onset and the infectious onset ME subtypes:

The first would suffer daily shortages of repair versus need of repair and force cells to go more and more of their time in the defensive-not-producing-ATP mode. The second subtype would be able to do the daily repair without too much trouble but would be overwhelmed by a strong infectious event and from that moment on no longer be able to out-repair the damage on a daily basis.

When seaching for “cytokine networks repair”, I get plenty of papers on cytokines and repair of the gut. In addition I got a paper on repair of facial nerves and on cartilage.

See for example the papers:

* Titled “A cytokine network involving IL-36γ, IL-23, and IL-22 promotes antimicrobial defense and recovery from intestinal barrier damage” from “Vu L Ngo, Timothy L Denning”

and a website reporting on this work in more understandable language https://news.gsu.edu/2018/05/15/new-cytokine-network-can-repair-tissue-damage-caused-in-the-intestine-study-finds/

* Titled “Immunobiology of Facial Nerve Repair and Regeneration” from “QuanShi-mingGaoZhi-qiang” saying

“Investigation on microglial activation and recruitment, T cell behavior, cytokine networks, and immunological cellular and molecular signaling pathways in facial nerve repair and regeneration are the current hot spots in the research on immunobiology of facial nerve injury.”

Note: Small Fiber Nerve trimming and shortage is a thing in ME/FM…

* Titled “Cytokines in Cartilage Injury and Repair” featured on https://www.orthopaedicsone.com/display/Main/Cytokines+in+Cartilage+Injury+and+Repair

* Titled “Inflammation in Wound Repair: Molecular and Cellular Mechanisms” from “Sabine A.Eming, ThomasKrieg, Jeffrey M.Davidson” saying

“Tissue injury causes the immediate onset of acute inflammation. It has long been considered that the inflammatory response is instrumental to supplying growth factor and cytokine signals that orchestrate the cell and tissue movements necessary for repair”

¨* Titled “Characteristics of cytokines in the sciatic nerve stumps and DRGs after rat sciatic nerve crush injury” by “Rui-Rui Zhang… …Sheng Yi & Hui Xu” saying

“Cytokines are essential cellular modulators of various physiological and pathological activities, including peripheral nerve repair and regeneration. However, the molecular changes of these cellular mediators after peripheral nerve injury are still unclear.”

* Titled “Respiratory tract pathology and cytokine imbalance in clinically healthy children chronically and sequentially exposed to air pollutants” by ”

L Calderón-Garcidueñas, R B Devlin, F J Miller” saying

“We hypothesize that there is an imbalanced and dysregulated cytokine network in SWMMC children with overproduction of proinflammatory cytokines and cytokines involved in lung tissue repair and fibrosis. The nature of the sustained imbalance among the different cytokines ultimately determines the final lung histopathology”

… and plenty more research showing the role of cytokine networks not only in dealing with infection but in day to day repair, repair after injury, repair after infection…

=> There is support for thinking that cytokine disregulation isn’t but a wrong response to infection or something to cause “undesired inflammation”. As a matter of fact, repair is a key function of inflammation. There are few other functions of inflammation (safe for annoying us and halting us to overextend us even further) then repair I can think of.

So, it might not even be too much inflammation that might be the problem, but inflammation that is too inefficient to repair and heal the day to day and the bigger damage we get throughout our lives.

Hi dejurgen,

Just wanted to know what helps you to get your brain working so well, especially having ME/CFS? (I guess you have a scientific background). I do value your comments, ie. when my brain is working okay 🙂

My bottle of perilla extract (which I started taking yesterday) says that it’s for “modulation of Th2 cytokines”. A web search reveals that “the signature cytokines produced by Th2 cells are IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13”. Since Jason found issues with IL-5 and IL-13, maybe this is why perilla extract helps some people with ME/CFS.

Might be. Researchers have been speculating about the role a shift toward TH2 dominance may play in ME/CFS for quite some time.

@TracyD, be on the watch out for it to thin your blood. That can be good, but you don’t want it too thin. I wasn’t able to take it daily, because it thinned mine too much with daily use. And I need thinner blood as I have too thick blood.

Wondering if anyone with positive EBV titers has tried the Professional Formulas EBV nosode and seen any changes? The Histamine nosode seems to have helped my MCAS issues. My EBV titer is off the chart high for several years now even though I don’t have an active case. My body is obviously reacting to something that it thinks is EBV or there are remnants of EBV provoking a response. This article sounds like a very likely scenario to me as my ME/CFS was caused by an untreated severe bacterial infection (Anaplasmosis) which I always assumed had “crashed” my immune system.

@T Allen, I haven’t taken those homeopathics, but I do use histamine to help my MCAS. Its a whole other approach and quit controversial, but I try to trigger my H2 receptors by adding histamine. The H2 receptors turn off as much H1 response and over release of histamine. So it moderates a too much release of my body own histamine. Working on this has helped more than just my MCAS, but POTS and brain fog. I’m no longer on antihistamines. More information about this is on Healthrising forum.

Hi Issie, what search terms should I use to find that discussion? I used “homeopathic histamine” and got no results. Thanks

Some may have more issues with virus and others with bacteria. Lyme for example is bacterial. A fungus found in my blood and a thyroid biopsy is found high in ME/CFS in this study.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2452231718300083?via%3Dihub

Those of us with CIRS and inability to throw off mold and biotoxin seem to hang onto things that the immune system should detect and destroy, but it doesn’t. We can also be predisposed to this by our genetics.

Great article and great comments . These results are similar to what I received from the EpicGenetics supposed trial. They were not specific with the results only saying I have improper cytokine production.