Whitney Dafoe’s published story provides the most complete account of severe ME/CFS yet

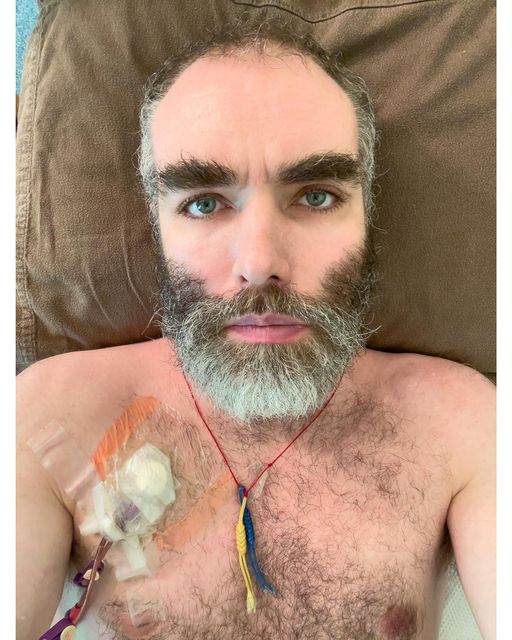

Whitney Dafoe’s painstaking and illuminating characterization of his descent into a severe illness, “Extremely Severe ME/CFS—A Personal Account“, was recently published in an edition of the Healthcare Journal that was devoted to severely ME/CFS patients.

Nobody to my knowledge has provided such a detailed account of what it’s like to be extremely ill with ME/CFS. It provides much room for thought and brought up some questions…Do stomach bugs tend to produce worse cases of ME//CFS? How about illnesses that are triggered in less developed countries. How are severe relapses generally triggered? These and other questions can be found in the poll at the end of the blog.

The First Hits

The first hit for Whitney Dafoe came in 2004 when he started experiencing a dysautonomia-like symptom – lightheadedness – which worsened after exercise when he was 21. Note that this problem occurred outside of an infection or other event. Something had slipped but no one knew what. Aside from that odd problem, he was apparently fine and was able to travel internationally.

While in India he had a “mild cold that never really took hold” for about 2 weeks but then came the first big hit – a mild case of diarrhea which nevertheless left him exhausted and with “severe ME/CFS”. Whether that was a sign of a propensity to an immune over-reaction or something else the fact that some sort of mild stomach flu evoked such a dramatic reaction was probably a bad sign.

Some strange problems were adding up but there was no cause for alarm. Returning to the States after a bout with pneumonia, he recovered to about 80%. Traveling to Guatemala in search of a cure after another case of “mild” diarrhea, his stomach shut down (we will see that theme again), and again, he lost all energy. That unusual reaction to what appeared to be a relatively mild bug indicated something strange was going on.

His journey, thus far, is in keeping with what we see in many long-COVID and ME/CFS patients. One of the more interesting findings to come out of long COVID research to date is that there’s clearly no need for some spectacular onset. Even the cold symptoms don’t need to be particularly strong. In fact, it appears that some people who didn’t experience any flu-like symptoms during the initial infection later came down with long COVID. That suggests that some people with ME/CFS who didn’t appear to have an infectious trigger may have had a hidden one.

A bit weaker and with his stomach still impaired, Whitney felt strong enough to hit the streets fundraising for an environmental organization but then tanked. This time it wasn’t a bug that triggered a relapse – Whitney simply overdid it – the first time this occurred. Interestingly the same symptoms he associated with the stomach bugs popped up. His body appeared to be producing them in response to exertion as well.

Now it got pretty serious. For 2 1/2 years, he was mostly housebound. (Whitney’s statement that he now had “moderate” ME/CFS underscores how off the charts ME/CFS patients’ functionally are compared to most other diseases. In how many diseases does being housebound constitute a moderate case?) After Whitney reluctantly moved back into his parents’ house, his ability to regulate his activities more, however, allowed him to improve a bit. Things were on a bit of an upswing.

The Big Hit

Then the autoimmune drug Rituximab (Rituxan) apparently threw his immune system into disarray, and he fell off the cliff.

Whitney was teetering when ME/CFS’s great hope at the time, sent him over the cliff.

After Rituximab, he was in a different situation entirely. Before Rituximab, he would overdo it, rest, and more or less return to baseline. After Rituximab, it was if once his reserves were used up – they were gone. Rest did not result in replenishment. If he overdid it, he would get worse and tend not to recover. This is where Whitney’s story probably diverges from many other people’s with ME/CFS.

He quickly developed new symptoms (pain in his leg muscles, unable to speak, hardly able to text, had difficulty tolerating small amounts of stimuli). He was still ambulatory, though, and was able to walk out to the yard or kitchen, and then later relied upon a wheelchair.

Whitney’s Rituximab downturn highlighted the powerful role the immune system is playing in his illness. While Rituximab is generally regarded as a powerful, but generally safe drug, it does deplete B-cells, and can induce low white blood cell and IgM/IgG levels, and probably many things we are unaware of.

Whitney’s Rituximab experience also points out how heterogeneous a group we are. While we now know that Rituximab is not a suitable treatment for ME/CFS, some people did get better on it.

About a quarter of the patients taking the drug in the phase III trial experienced a “serious adverse event” which required hospitalization, but because 19% of the placebo group also experienced a “serious adverse event”, the vast majority of which also required hospitalization, the drug didn’t appear to be causing significant problems. The authors concluded that “few (of the) serious adverse events had a suspected or probable relation to the study drug.”

While it’s frightening watching someone descend into the kind of hell that Whitney fell into, note that Whitney’s big crash was triggered by a bad reaction to a powerful autoimmune drug – something most people with ME/CFS/FM will never experience.

The Next Hits – An Emotional Event and Stomach Problems

Next, an emotional event sent him spiraling downward and he became bedridden – where he has been ever since.

Next up, the switch from yogurt – an important source of nutrition for Whitney – to turkey patties was too much for his already very fragile stomach. Ironically, his stomach had slowly been getting better but got worse when he switched to something he hoped would help. It made sense that eating a higher protein food might help, but the more difficult-to-digest food had a dramatically negative effect. Whitney noted that it was as if his stomach had PEM.

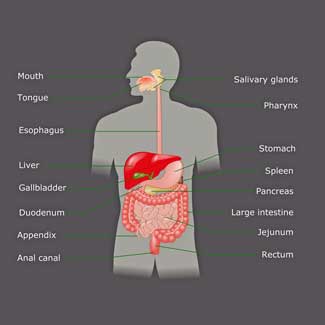

Stomach issues triggered several of Whitney’s relapses. (Are they more common in people with severe ME/CFS?)

With most of our energy going to simply keeping our bodies alive, and digestion taking up about ten percent of our energy usage, digesting food carries a high energy burden. It’s one of the most energy-intensive things we do – and it’s why small meals are preferred.

When Whitney switched from yogurt to turkey patties, he began taking in a food that required much more energy to break down.

Whether that was the issue – Whitney’s already fragile stomach broke down and he was able to eat less and less and less without extreme discomfort. Eventually, he had to stop eating at all and was put on a PICC line which fed him intravenously.

Whitney’s ME/CFS probably didn’t begin with stomach issues. The first warning signs showed up when exercise brought on light-headedness – but after that, stomach problems have featured in three significant relapses. They also seem to be present in quite a few severely ill people.

Caroline’s blog – coming up soon – will focus on the role that those issues, and the malnutrition that likely ensues, may play in making the illness worse.

The Transition from Severe to Extremely Severe

As Whitney got progressively worse overdoing it would cause him to lose ground which could not be regained through rest.

Whitney was mostly bedbound, was unable to speak, and was on a PICC line when another incident tipped him over yet another ledge. Allowing the film crew from Unrest to film him when he had recently overdone was the straw that broke the camel’s back.

After that, he could no longer write, or even use his prewritten cards to communicate. In fact, he almost couldn’t communicate at all. Except for going to the hospital, he has not left his room nor spoken to another human being in seven years. He hasn’t eaten food or drunk liquids in six.

Mindfulness Helped

Unable to communicate, read, text, etc., Whitney had become almost completely isolated. Noting that negativity made things worse, he turned to mindfulness training. Mindfulness wasn’t an answer for his physical problems, but he said it was crucial, in helping him get through the hell he was about to go through.

“I realized that if I could put a negative tint on everything, I could put a positive tint on everything too. I began practicing and training my mind to think more positively. It was not easy and took practice, but this eventually became integrated into how I saw and thought about things. It was crucial for what I wound up going through.”

It’s easy to see how the stress from engaging in negative thoughts could have such an effect. Stress triggers cytokine activity and inflammation, and potentially symptoms like pain and fatigue, in much the same way that infections do. It also activates our fight/flight (sympathetic nervous system) response, increases our heart rate, and mobilizes our energy stores for action.

Being stressed or upset is simply an energetically expensive state to be in – precisely the kind of state Whitney could not afford to be in. He did everything he could to avoid that.

The Mental Crash – A New Distinction

He entered a new phase with his “mental crashes” and linked – in what I think is a key insight – the mental crashes to his low energy state. At this point, he was so energy-depleted and weakened that, as noted before, that simply having thoughts about something negative – or even sometimes anything at all – could have devastating effects.

“I was in a nightmarish situation where my mind started playing tricks on me, flashing subjects I could not tolerate thinking about into my mind at the worst times and causing mental crashes. I was completely lost in a corner of my mind trying to keep my brain activity to a minimum. It was horrific.”

He even became unable to tolerate mental stimuli like patterns on a shirt. He couldn’t do something “complex” like moving if his brain was attempting to also attend to something like noise. This is a brain that was so depleted that it couldn’t handle more than one simple task at a time. Even engaging in one task took special mental effort (see below). I wonder if the medical profession has ever been acquainted with problems quite like these.

“I couldn’t tolerate any colors or patterns on them. I also became sensitive to text like logos or labels on things because it is impossible not to read text that you see; it is something we do instinctually at this age. Reading required more mental energy than I had and caused a mental crash. Due to crashing from the text I could read in my room, I wound up becoming sensitive to text I couldn’t read as well. Just knowing it was there was extremely stressful.”

One can see Whitney’s brain reaching out to attempt to decipher the words, leaving Whitney recoiling in pain. Note that that action – attempting to decipher the words or patterns on a shirt – was done below the level of consciousness. Most of the actions our brains have us take, occur, in fact, below the level of consciousness. They are more or less automatic.

The hot flush he experienced when stimulated too much suggested perhaps a mast cell or adrenaline/autonomic nervous system reaction when Whitney became overstimulated.

“The symptoms of this type of mental crash were usually a hot flush starting in the back of my head and moving down through my whole body, followed by an adrenaline release that temporarily made me a little better, but was later followed by my mind getting much worse.”

It wasn’t just negative stimulation. Even good stimulation could overwhelm him.

“As I said, during this time, my brain was extremely sensitive to crashing from the tiniest extra interaction with caregivers or even thinking about the wrong thing, or from thinking about something for too long. I put all my focus on being perfect and then, if nothing went wrong at night when my caregivers were gone for a long period of time, all night, I could think a little bit.”

Whitney described existing at times in a kind of limbo-like existence connected to only shards of his former self.

Whitney noted how difficult it was to have someone in the room. It clearly would have been easier to have a dog in the room. There’s so much less to think about with a dog. There’s so much more packed into a human voice than, say, a dog’s bark. As Whitney pointed out, it’s the complicated connections that probably took up too much of his brain’s energy reserves that were the most problematic.

“Having someone in the room, especially, puts me over my limit. The combination of thinking at the same time is extremely overwhelming. I have to meditate on a couple simple ideas or memories, and if my mind strays, even for a moment, it can be devastating.

The stimuli, whether it is a sound, a sight, smell, or touch, could connect my mind to something and it was this connection that often pushed my mind over its limit. The sound of people talking, for example, was too much human connection for me to tolerate. Interestingly, it was much easier to tolerate hearing people I didn’t know, like neighbors, talking. This is because It caused much less thought because I didn’t know the people.”

This is a key insight that appears to lead back to a brain activation pattern, which in turn, seems to lead back to an energy production problem. This is why ME/CFS seems more a disease of insufficiency than anything else. When Whitney’s brain was overwhelmed, “he” would recede … and exist in a kind of limbo state. In the dead of night when everything had gone right and he was utterly calm and at rest, though, his brain had the “energy” to work properly and he could think.

“I let my mind wander. I usually thought about making things. I have a whole business plan for multiple restaurants, buying and fixing this local natural food store, and lots more. I also thought about art projects in-depth, of course. I lived for that time of daydreaming at night and somehow made a sort of life out of it.”

Whitney’s greater difficulties during the day when more stimuli were present made sense given what we know of ME/CFS/FM. People with ME/CFS/FM have to exert more energy and use more sections of their brains to process outside stimuli. They also have trouble shutting off attention to innocuous outside stimuli – hence Whitney’s need to use ear and eye protection to remove all possible stimuli.

Whitney’s problems with controlling his mind probably rings bells with many people with ME/CFS who experience their concentration problems worsening as they become more fatigued. While Whitney is at the very end of the spectrum functionally, his experiences make sense with what we know about this disease.

Visualization Helps – Thinking Does Not

Thinking about moving didn’t work, but at times visualization did.

“If I thought about any movement too much, it became extremely difficult to do because anything intentional was difficult or impossible. I used various methods over time. One was to visualize the movement I was going to make over and over until suddenly my mind released the necessary adrenaline and I could tell that I could do it safely, and then I could pick it up with no problem but had to follow my pre-visualized movement.”

Visualizing his movements ahead of time brought relief.

It was as if visualization temporarily cleared a path in his brain to take safe action. When we move, our brain, without our knowing it, actually plans out our movements ahead of time.

Visualizing the movement may have helped that process – smoothing things out so that he could take very small moves without causing problems. (At this point Whitney’s system could be discombulated by having to make small moves in bed.) Athletes know that thinking only gets in the way of excelling in their sport. The goal is to be mentally clear and let the movement happen naturally.

That highlights the fact that thinking about a movement is very different from actually moving. Thinking about that possibly perilous action may have brought up all the pain, etc. that was possibly associated with it, causing Whitney’s brain to put a chokehold on movement. Whatever was going on, visualizing, on the other hand, was a dramatically different way of approaching the movement problem.

Note that while energy problems were there, something other than a strict energy problem was also in play. The energy to do the action was there if it was visualized beforehand.

“Crash Memories” Make Things Worse

“If I crash or get hurt from something, my mind gets what I think is a form of physically induced PTSD caused by my stress or fight/flight response being turned up as high as they could go. When I crashed from something, I developed a stress response to it and became sensitized to it, so I had to be very careful not to crash from the few things that I was able to do or think about. These ‘crash memories’ slowly built up over time.”

Our brains have a kind of shorthand trick they do. Instead of meeting a situation newly, they take a situation, relate it to a similar situation that happened in the past and then pump in thoughts, feelings, attitudes, and actions associated with that situation. This is a completely automatic response that goes on underneath the level of consciousness.

Consider what happens, though, when virtually every situation evokes danger. Everything evokes a stress response, which then eats up more energy reserves, produces more pain and fatigue, and creates a crash. Perhaps it causes the “crash memories” (to) slowly buil(d) up over time.” Trying to push through this further reactivates the stress response – causing the “crash memories” to build up even more – and producing further debilitation.

Visualization helped Whitney bypass those crash memories a bit, but it was two central nervous system actiing drugs that had the biggest impact.

The Ativan/Abilify Effect

“The Klonopin and Ativan I later took helped me reset these Crash Memories, so they didn’t build up. I’m now able to crash from something and let it go and do it again (with the same energy limitations as before, but no added stress or limitations).”

Whereas Whitney’s brain was stuck before in a kind of defensive, PTSD-like state, it was now able to calm down a bit.

Ativan (Lorazepam)

Both Whitney and his parents dreaded him having to go to the hospital, but taking Ativan (lorazepam) changed that.

“Going to the hospital, especially for the first time, was incredible. I had no idea Ativan was going to have such a profound effect on me. I was preparing to get way worse and have a terrible time and crash horribly. Instead, I improved and was calm and got to enjoy things like seeing the sky for the first time in 6 years: all the sights of the real world out the window of the ambulance.”

Lorazepam (Ativan) is a benzodiazepine used to reduce anxiety and calm the brain down. Interestingly, instead of dulling the brain or hammering it into submission, it stimulates the inhibitory pathways of the brain. Ativan triggers the expression of the brain chemical GABA, which then inhibits the excitatory brain chemical glutamate. In 2013, Marco proposed that glutamate toxicity played a role in ME/CFS.

Unfortunately, Ativan can only be used for a short time, but it can work wonders when used – as Whitney did – to get through difficult situations. Klonopin is another GABA-enhancing benzodiazepine that many people with ME/CFS/FM have found helpful. (It can result in dependency and cause withdrawal problems).

rTMS is another potential therapy (which is being studied in conjunction with Ativan) which inhibits brain activity by exciting (in a different way) the inhibitory circuits in the motor cortex. The Solve M.E. Initiative is funding an ME/CFS pilot rTMS trial.

Problems with underperforming inhibitory pathways in the brain seem to be a problem in these diseases. In fibromyalgia, the pain inhibiting circuits have difficulty reining in the pain-producing circuits. In ME/CFS and FM, the inhibitory arm of the autonomic nervous system – the vagus nerve (parasympathetic nervous system) – is not controlling the sympathetic nervous system. The prefrontal cortex may not be correctly damping down fight/flight messages coming from the limbic system in ME/CFS and FM.

Abilify (Aripiprazole)

Abilify had an even more dramatic effect than Ativan. In 2019, Whitney started off very slowly and ramped up from .25mg to 2.0mg over about six months. A month or two later, it began having an effect.

“Abilify seemed to be changing something at a deeper level. I had more energy and could slowly tolerate more things that used to cause me stress. For the last 6–7 months, I have continued to improve, tolerating more and more things that used to make me crash from stress and over-stimulation.”

Of course, it was a matter of degree. Whitney is still bedbound, is still on a feeding tube, and isn’t talking to people, but he can stand in the shower (for a very short period of time), produce a piece like this, etc., and tolerate so much more.

Tracing Abilify’s specific effects in Whitney is impossible given that: a) it affects so many different receptors (5-HT1A, 5-HT2A, 5-HT2B, 5-HT2C, and 5-HT7, dopamine D2 and D3, adrenergic α1a, and histamine H1 receptors); and b) we have a general lack of knowledge about how drugs like this affect the brain; i.e. (“How its unique intracellular signaling effects impact clinical symptoms is not known”.)

It’s interesting, though, given the focus on mast cells, that Abilify came out of a search for better antihistamines. It’s also believed to rebalance the dopaminergic system. Plus, recent rodent studies suggest that Abilify may also have some interesting energetic impacts and may “impact insulin, energy sensing, and inflammatory pathways” in the hypothalamus. If Abilify is impacting neuroinflammation, hopefully more effective “Abilifys” are on the horizon as efforts to find more effective neuroinflammation busters have ramped up in several central nervous system diseases.

Vyvanse (Lisdexamfetamine) is a different kind of drug – a stimulant – which induces the release of dopamine and norepinephrine, which paradoxically has calming effects on people with ADHD (attention deficit hyperactivity disorder) and worked well in one ME/CFS study

Whitney has a long way to go, but he’s come far from being just strong enough to bear witness to what he called his “state of non-existence”. So, what is his story telling us?

I believe it’s suggesting that in some cases ME/CFS may be laying down its tracks long before it reaches up and throttles a person’s functionality. His story is certainly drawing attention to the role the stomach may play in the severely ill. It’s demonstrating that the size of the initial trigger may not bear any resemblance to the ferocity of the illness.

It suggests that the immune system probably plays a core role, that an activated stress response can make things worse, that visualizing may be able, at least to some extent, help with movement, that ME/CFS seems to be a condition of insufficient energy production and some really bad wiring.

Most astonishingly and encouragingly of all, it indicates that Whitney, immobile, masked and earmuffed, fed by a PICC line and hardly able to communicate, was waiting there all the time to re-emerge when the conditions were right. Whitney is still not talking or walking but he is indubitably there and thinking clearly and as Stephen Hawking did with his, finding ways to communicate

His story is also demonstrating how much we don’t know. Why did Whitney respond so poorly to Rituximab when others did not? Why when Whitney was at his worst did Ativan and Abilify work? And when they did work – why didn’t they work even better than they did? What other central nervous system-acting drugs might help?

There are many questions but few answers. Whitney’s story, though, gives researchers and doctors a new understanding of what the extremely severe ME/CFS experience is like.

A Severe Illness Poll

A poll prompted by Whitney's story - for everyone (not just those with severe illness).

And I think I’ve had it hard!

Thank you for sharing his story. I hope he can see the day soon that his life can be almost normal.

I have been ill since 1966. Has anyone else been ill for that amount of time?

I was just wondering how many of us are over 70 and still living with it?

I can relate to his story.

I have lost hope that I will ever be well.

Thank you for the courage to tell your story.

I became ill in 1956 after mono.I remember the moment when I went to get up and just couldn’t move. It’s frozen in time the way people remember where they were when JFK was shot or the Twin Towers came down in 9/11. I was 16 and I’m now 80. I have lived my whole life with what was diagnosed in 1986 as CFS. Wonderful doctors along the way tried their best to help me, not successfully. Many hospitalizations, lots of periods of being bed bound or house bound. One bed bound period post hospitalization for pneumonia sounds a lot like Whitney’s, unable to eat, tolerate light or sound, walk, talking took to much energy, severe pain with no pain meds. Fortunately my mother had trained as an RN in 1920-1923 when bedside nursing was not only a skill but an art. Her training included a year where a woman from Sweden lived at her training school for a year and taught them Swedish Massage. Fannie Merritt Farmer whose Food and Cookery for the Sick and Convalescent had been published in 1922 also came and taught at her training school. Finally an artist friend who ran a hole in the wall health food store, incredibly fringe at that time, knew Adele Davis pioneer in food as medicine. We sent her a letter detailing my symptoms and she sent back a list of supplements, how much and how to take them and what company provided quality supplements. And that’s how my mom pulled me through, took 8 months but I got well enough to work. No doctors involved, just her nursing skill. Have had subsequent episodes of bed bound/house bound but have never been that sick again.Still use supplements as well as prescription antivirals and pain meds and massage and anti inflammatory eating.Now mostly housebound, spend most of my time resting. Have a wonderful Nurse Practitioner and Board Certified functional nutritionist/neurologist. Consider myself very lucky to have them.

I’m 78 & have had FMS/CFS/ME since I was a child. Did anyone know anything about them back then to help me – no. Severe fatigue, pain, hypersensitivities, cognitive problems, Rheumatic Fever, infections/viruses/EBV, & constant testing, bloodwork, x-rays/procedures, & an unnecessary exploratory abdominal surgery at the age of 12. Many relapses. Progressive w/aging. Mostly housebound. Many comorbidities + additional illnesses. Spinal Stenosis- 4 surgeries. Stage 1 Lewy Body Disease diagnosis 2020. Emotional & physical stress. Anxiety & OCD since the age of 7. Living independently for as long as I can.

I’m so sorry for your loss of most of your life, Rosemary and Kat.

I first became ill at 7 years old with some form of pneumonia. It took a long time to recover then. Then I would faint often and my mother recognised something in me similar to herself(I diagnosed her as having g had almost lifelong ME/CFS in the 1980s)

I trained as a RN but often found I collapsed with fatigue easily.

At 28 I had a Coxsackie B infection from which I did not recover.

Relapses occurred and a general anaesthetic caused complete gross muscle weakness for many weeks.

I went into heart failure and was diagnosed with cardiomyopathy at age 50.

I am now 72 and seem to have an over-active immune system as others here described.

I have found Klonapin a very helpful drug.

Not mentioned in the survey.

My family seem to have a genetic propensity to this illness with my mother, one son a sister and a niece suffering g from it as well

My family has also seemed to have a genetic propensity to ME/CFS. Both of my kids. We all had different viruses that seemed to trigger the ME/CFS but once we each got the virus we seemed to never recover and went onto having all the symptoms of ME/CFS and have all been diagnosed. So, I think it can be from different viruses it is how you genetically are prone to not be able to heal and it set off the disease of ME/CFS.

Rosemary, you have touched a cord. So difficult in this area of health. My daughter became ill at 13 (on her birthday) and has never recovered. She is now 25 with no change in sight. Still have not given up on finding something to help her. Am currently working on genetics and hormonal testing (Dutch test) to see if we can find an avenue to pursue. Some past suggestions have sadly either failed to make a change or made her worse. But… never give up!!!

I would like to add… all the responders are female. That tells us something maybe!

Whitneys story is so complex and sad and uplifting all at the same time. Here’s hoping he can get more of his life back.

My sister and I and a friend got a vaccine, I was around 8. None of us have been right since. All of us DX with FMS and ME/CFS. That vaccine caused us to get sick and miss a year of school. None of us could walk or hold our heads up from a pillow. After that, at age 21 I got a ruptured appendix, (that wasn’t operated on until 2 years later- no insurance), colitis and pneumonia all at the same time……that did me in worse. (Not to mention the 8 Abdominal surgeries to clean up the mess. Ending in a full and complete hysterectomy at age 36.) I was born with EDS (connective tissue disorder) and had POTS since being a child. So I have had this most my life too. And I’m 18 + 43 LOL. (Forever 18….. in my mind. ?)

True long haulers! We are still here to tell our stories and we are still looking for a better “purple bandaid ?”. I would say in the last 2 years, that Dejurgen and I have been researching together…. I have found some. I am better in so many ways. Not well, all the way, but improvements for sure. Its all about quality of life with whatever quantity we get.

I have a goal for each day. I try to find at least an hour of JOY every day. I find something that makes me happy, puts a smile on my face and makes me appreciate the gifts that God allows us to have and the beauty he created for us. That has helped me stay more positive…….despite myself.

I’ve been near death many times…. but I chose to try to Live. Not afraid to die, but having courage to live in a very dysfunctional body takes a lot of courage and determination. As Whitney said, we need to stick around and show that it can be done and we can get better. Even if the baby steps we take seem insignificant….. we may can make a difference. Science is advancing and even though I have had this most my life and am umHummmm “young older”, I feel we can have improvements with our bodies and our lives. I haven’t given up looking for more WHYs. And I hope others won’t either. We are soooooooo close. That “purple bandaid ?”, is almost ready to be applied to cover over the boo-boo. We may not can “fix” it all the way……but we can make it better.

I’ve lived with this for 21 years! One day my life changed forever. I was 43 and very active person. I loved to workout but can’t anymore! I’ve tried everything that I thought might help. I’ve spent thousands of dollars looking for an answer to fix what was happening to my body. It has taken me 21 years to realize that it’s Chronic fatigue syndrome I’m dealing with and there’s no cure for it! The hardest part is that you look fine and people have no idea what your going through! I’m so blessed with a husband that does understand! He’s done so much research on CFS. And with what I go through and reading about it has made him very aware of this illness!

I have been ill since 1963

I caught a flu while visiting England in 1976–never before had flu & had been quite healthy. I was ill for two weeks, recovered but then had intermittent relapses for next ten years. In 1992 I had to quit work, hoping rest would improve my condition. It didn’t. No diagnosis until 1994. After returning from a difficult trip (cruise) to Southeast Asia I was much worse with symptoms of fibromyalgia–muscle stiffness, soreness, etc. that was different than previous CFS symptoms. Diagnosed finally in late 1994. I am now 73 and mainly housebound for past four years. I was a patient of Dr. Cheney’s for a time and have tried just about everything. Deep tissue massage, chiropractic & acupuncture brought me most relief, though temporary. (3 month remission after chiro/deep tissue work). I cannot afford any alternative treatments now. I feel both discouraged and lucky that I can still take care of myself and the cat, but worry about future as I am getting worse and have no caregivers.

I am sorry you are at the age and worry since you have no caregivers. That worries me. I am hoping you will have someone to help you. I am 65 and I have no caregivers, and it is very difficult especially with the cost of living increasing at such a fast rate. I will be keeping you in my prayers and all of you who need help and don’t seem to have enough help. It really upsets me and worries me for all of us suffering that really need compassion, believing and help. It is sad to have this illness and then it is even worse that there is so little understanding and progress for a cure or cause.

in my 70s too, taking care of myself is impossible. bath, can’t, eat frozen foods in microwave, too ill just too ill.

Rosemary – I’m so sorry to hear of your lifetime suffering, but I’m basically in the same boat.

This Thanksgiving I marked the 50th year I’ve suffered to the point of being disabled by ME/CFS. I am 69 years years old and contracted ME/CFS at 19. Within six-eight months, I also contracted hyperadrenegic POTS, which actually has been more limiting and life threatening to me than ME/CFS. Probably some of the 33 ICU visits were a combo of hyper POTS and MCAS.

I also have zero hope I will ever be well, but I DO have hope to improve, which has happened in the past eight years (finally). I actively read Health Rising and carefully try new treatments and approaches.

Wishing us all the luck – Elegiamore

Wow – I really acknowledge you for your resilience Elegiamore! Wishing us all the luck as well! Glad you’ve found some things that helped 🙂 Take care!

Wow, thank you, Cort! You really mined his article and brought up many things to think about. As usual, you are amazing and so helpful.

Thanks 🙂

Janet said it well. I got 2-3 times more insight reading Whitney’s article and then your article.

Dear Cory,

I wrote a reply.

I then got informed I had double posted! I didn’t mean to do anything sneaky, honest. I’m just brain fogged.

I can’t see my post now. If you didn’t think it was helpful that’s fine. But I hope it wasn’t rejected just because I accidentally posted it twice!

I’ll try to be more careful this time!

Thank you for ALL the fantastic, generous, intelligent work you give!

Marguerite

Hi Marguerite,

I also got the ‘double posting’ error yesterday, and none of the three replies I posted (1 to dejurgen, 1 to Lisa Petrison) have shown up here (yet?).

I doubt it’s you – more likely some error on the website.

But perhaps Cort can look into it for us.

Dear Janet,

Please don’t reply if you’ve no time…or perhaps someone else can answer my question?

Why stop the Ativan?

I took Ativan for more than two years… AND it was while taking Ativan (plus Valium) I know, most regular doctors get *concerned”, but it was while taking Ativan plus Valium (each night) that I recovered 90% from ME/CFS. I also used Pacing and the CFIDS Self Help site.

A horrific family incident of abuse set me back to 25%. At which time, I could not longer afford to obtain *brand* Ativan or *brand* Valium. The Ativan which used to cost me $20 a month was now $3000. I’ve since tried various generics but always wonder if the *brand* Ativan is the missing healing factor?

To my knowledge I have never become addicted to Ativan or Valium … I took .05 Ativan each night plus 5 mg Valium for a year… and recovered to 90% from #ME/CFS. This included a complete healing and freedom from brain fog.

I’ve since had periods of 35% functionality, including ability to travel a little and go ice skating. But I’ve never been free of brain fog since relapse.

I have also not had access to brand Ativan or Valium since my relapse.

Btw, when I healed 90% from ME/ CFS I was no longer taking the Ativan or Valium because I no longer had sleeping problems (a key problem for many of us with ME/CFS) so my relapse did not occur because I suddenly stopped taking Ativan and Valium.

I now take both generic to help me sleep. Sigh.

If Ativan helped your son, why did you need to stop it?

I also welcome all thoughts on my anecdote.

Became ill with mono in 2012, recovered in 2014, relapse in 2014, now at 25%.

Marguerite, I can’t speak for Janet, but generally speaking: I can imagine people with very severe ME would not want to risk benzodiazepine withdrawal, which is very difficult and potentially dangerous (can cause seizures and death if not medically managed) and would almost certainly cause a relapse in someone like Whitney. You may not have had this problem, but I believe most people would develop physical dependence taking benzos every day for years, putting them at risk for these problems.

You habituate to it and it loses its effectiveness

Hello troopers,

I continue researching to find the bottom of cfs and how fbro is related, or how it is unique. I sm trying to do so in the context if all pandemic affects. I do this for the sake of a friend but your openness about cfs’ heavy impact moves me. Cort might use a long comment I made recently here as a blog since it is research-based. Hopefully.

But here is how it strikes me after

1.5 years of reading, with regards to the women who have been suffering since the 60s on this page:

Women’s bodies use/need more cortisol than men’s do. Their hormones also change balance frequently in comparison. It strikes me as no coincidence, after all this time, that women are more prone to cfs, but also to osteoporosis. Hormones govern movement of calcium to and from the bones. A lack of vitamin K2 in covid can impair calcitonin and the lack can allow calcium to be stored in soft tissues , esp the blood vessels. That is why K2 is also used to augment covid management. That is because cytokine storm leads to the atherosclerosing of vessels by first depositing calcium where the damage is, then cholesterol and plaques sticking to that. In this context you can easily see how diabetes, obesity and hypertension all predict a worse covid outcome.

As you must realize by now, calcium either stored in the muscle or brought to it for exercise is crucial to success.

Since cortisol is the stress-management hormone, and since chronic high cortisol levels can lead to adrenal fatigue, it does not surprise me that many hormone functions normally supplied by the adrenal glands suffer if the HPA axis decides that cortisol is the priority.

(epinephrine, norepinephrine, aldosterone suffer, progesterone) Yes, most progesterone is made in the ovaries, some is made in the adrenals.

Estrogen dominance over progesterone has many side-effects:

https://www.thehollandclinic.com/blog/estrogen-dominance

The talk of hypovolemia and of high platelet counts in cfs make sense to me because:

a) aldosterone is a little-known hormone with the huge job of retaining salt, the electrolyte. If your kidney instead excretes the salt, water must leave also, and you may be hypovolemic. That makes the heart work harder and the vessels need to stay constricted.

b) constant inflammation definitely does bring ongoing atherosclerosis.

The only true blood thinner is water. Anticoagulants do not thin your blood.

Finally, I mostly want you to think of cortisol being

a) more prominent in women

b) possibly affecting hormonal balance

Estrogen encourages higher amounts of calcium in the bones, normally. But sometimes too much of something and too little can both result in similar problems.

So this comment is to encourage you, if you have not, to observe your hormonal levels, blood volume and symptoms with relation to cortisol *dominance*. Maybe only you can put the relationship together and for once explain certain symptoms.

Chris

Off-label use of Doxepin can be used to calm the mast cells in Whitney’s brain (likely at the juncture where the cerebrospinal fluid enters/exits the brain- this juncture is filled with/surrounded by mast cells according to a Harvard-facility doctor’s webinar that I watched a while back -I cannot remember his name though). I have been using Doxepin for 6-months for this purpose with significant improvement in certain symptoms, namely overall SUFFERING, brain pain, brain pressure, neck and spine ligament laxity, and feelings of reduced blood flow to the brain. I informed Dr. Bonilla at Stanford initially that Doxepin was having a dramatic effect. I have not spoken to him since but I have now been taking it 6 months and improvement continues. My allergy/immunologist prescribed Doxepin as a histamine-4 receptor drug for my brain. He said it is the only antihistamine that will work in the brain. Doxepin is normally given for depression but in my case it is being given for off-label treatment of mast cell activation disorder in my brain. It is as important and imperative to my health as naltrexone and pyridostigmine.

Hello all of you dear champions of living with this alien host in our systems. I believe CHS attacks those of us that really care about bad situations that happen to others and are quiet possibly the kindest people on earth. I have been bed-bound only 8 years. At first I thought I could not live this way. But now I focus on what I can still do.it has helped me tremendously. I also quit caring what other people think of me. In time, we all come to an understanding of suffering. May all of you find your own joy and keep it no matter what.

Cort, I know it’s too late now for this particular poll but in the future it would be interesting to add a question about M.E. starting when one was traveling to a 1st world country.

My M.E. started when I traveled to Denmark. I have lived my whole life in a poor country.

I know you were probably aiming for “exotic” bugs that most westerners are not usually exposed to, but if M.E. could be triggered by being in an airplane with lots of people exposed to regular bugs, exertion of a journey, eating new foods or drinking water body never encountered before, or any other aspect of travel itself, then by just asking about travel to 3rd world country and not others the results may be skewed and make it seem like there’s something about 3rd world countries and not travel itself that’s a trigger.

Added 🙂 yes I was thinking about exotic bugs but any bug that we might meet in another country might be exotic for us – plus there are all the other new things…the air travel, the foods, etc. Thanks for the suggestion.

Why is it that lots of us get/got sick other than our own regular environment?

I wanted to add, my body seems to EAT colds now. 2-3 days and I’m good.

Yes, this was an issue I had with the poll. ME/CFS apparently revved up my immune system so much that, for the first 7 years, I never had a single cold or stomach bug, despite having two young children who were bringing home all kinds of bugs. For the subsequent 10 years, as I’ve regained greater function, I typically have very short, light colds. I’ve only had two heavy colds in the 17 years since I got ME/CFS, and no other infections. And I’ve been working very part-time in an elementary school for years now…basically in a petri dish. I like your observation that your body seems to EAT colds. Exactly.

Yes, this is the exact same with me and many others. The immune system is hyper active.

Same for me re colds. I get them rarely now, and when I do, they don’t last more than a couple days. I used to get them a lot and they were a week long or more before I was hit with ME. (I believe what pushed me over the edge into ME was a bad sinus infection in 2008).

Me too!

I don’t appear to get colds or flu anymore, though I am housebound and only see a few people, but even when those I live with have bad colds I only get a ‘cold’ reaction that lasts a few hours. Lateral blood tests over the last 5 years show I have a permanently overactive (and increasing) white blood count that follows a yearly cycle.

My daughter is the same. Her immune system is vigilant to the extreme. The odd sniffle… and she is done! Then again, she did NOT have a lot of contact during her high school years and university years as a part time student where she appeared for lessons and debunked immediately to get home for rest!

I will add perhaps diet may also be a factor. I feed us really well (Patting myself on the back now?) and i too avoid bugs etc. never seem to be afflicted except lightly and for only a short time.

Yep, I don’t think I’ve had a cold since I got sick (two years), and if I did, it wasn’t distinguishable from ME. That wasn’t normal for me before.

Have any of you looked into mycotoxin mold illness. Seems to be the mixing link after many years of being very ill.

Ditto for me and no colds – or flu, except very rarely. In the 35 years I’ve had moderate (per Whitney’s definition, anyway!) ME/CFS I’ve had what might have been a flu four or five times. My main symptom that tells me I’m ‘sick’ is a touch-sensitive creepy-crawly sensation in the skin on my abdomen and upper legs. However, after the worst of those flu(s), I ‘suddenly’ also developed Rheumatoid Arthritis.

(I should have added that ME/CFS for me also started with a ‘flu’ – the worst one I’ve ever had. It lasted seven days instead of the usual four. That was in 1986. The one that ended with RA was in 2004.)

I also became ill after a bad flu in 1986, which was possibly triggered by a traumatic experience.

I wonder about fecal transplant with his case? Peace to you.

Me too! I REALLY wonder about that….for him and for all of us really.

Thank you Cort for a truly masterful piece. Bravo a hundred times to you. It was very useful for me to read this analysis and to compare it with what happened to my daughter. On the issue of feral transplant, I would be happy to hear form others on this. We had booked an appointment for a Fecal transplant and then my daughter ended up in the hospital just a day beforehand, so it was nixed. But I did speak to Dr Borody in Australia, who had some success with these transplants. Since them, I am reading that folks who work in this field are suggesting that one must find good matches, as this is in fact a ‘transplant.’ I am not sure what is involved in finding good matches, but it seems to be getting complicated. If anyone has more up to date info, that would be great. But one CFS doctor in the USA told me not long ago that it may not be successful unless other issues are first addressed: GI infections, immune system, etc. Hope there are folks out there who know more than I do. Thank you in advance. And Cort you are a marvel. Thanks.

I know the pool of patients must be small, but are there any unusual cases involving ME/CFS and organ transplant? Particularly liver?

One thing i did hear about faecal transplant is that the diet of the donor should be somewhat replicated by the recipient so that the various species implanted are able to continue to survive.

Do not know if this is just conjecture but it seems to make good sense in that the microbiome needs appropriate feeding!

Cort, often my stomach precipitates a crash but it doesn’t feel like a stomach bug. More like an IBS attack. Lots of histamine.

Perhaps that could be a nuance to the stomach bug choice.

It’s like I have an alien in my stomach when I crash. Pressure, movement and malaise

My osteopath recently drew my attention to experimental use of laser light, applied to the outside stomach skin, to alter the microbiome of people with Parkinson’s. It might not work if your intestinal microbiome was truly messed up, but if you are just moderately out of balance, it might restore balance and sounds pretty low risk and low expense.

Yes, I tried this. It made me a little bit better for a while. But then it kind of reached a max in its potential, and I got PEM with a higher “dose”. So I stopped.

Tiffany, are you referring to near infra red and far infra red???

I am informed that this can also affect the microbiome.

This is my first time reading about Mr. Dafoe. My first reaction, is what a weird story. It’s so familiar and so similar, yet so different from me so I wonder how can there be so many similar things yet so many different things. WTF is going on you know!?!? One of the weirder things to me is how so many people swear on completely different things that help them, it’s just so f*ing weird that I have to wonder are we all just getting better at that point in time accidentally, would this just run it’s course regardless of interventions. I had an illness in twenties and I swear I got better after taking mepron/zithromax I had almost a complete remission. Then I get sick in thirties, seems like a completely different illness and so far nothing is helping me as I make my way through forties. My mom has been sick for 30-40 years, she claims she was cured by anti candida diet she swears that even with symptoms that still wax and wane that diet cured her. Anyway, I’m just puzzling out loud, the only question I do have (and I will read more about Mr. Dafoe but can’t go down this rabbit hole tonight) is has he been completely worked up to check for mitochondrial disorders? I see his dad wrote a book called “The Puzzle solver” looks very interesting

I have a suspicion that, like you said, some people who improve or recover may have done so regardless of whatever intervention they were trying at the time. Many of us are often trying one thing or another, and if someone is always trying something, it will look like that thing made them improve if they were going to improve anyway.

That’s not to say nothing ever works, of course (Abilify really is looking promising).

I can soooooo relate!

Glad you’re better Whitney! And hope you keep improving. Every step forward gets us closer to our full puzzle coming into view. Thanks for putting your story there for us to connect to. Its so encouraging that you are on a better journey now.

I think Tramadol and Bentyl have been the best two combo medicines I’ve found. For the same reasons. Tramadol works on all the neurotransmitters and also NMDA and calms glutamate down. It also has calcium channel blocking properties that help vasodilate veins and help with blood flow. It also has anti-inflammatory abilities. And works on opioid receptors too. We make those in our bodies too and they can be too low, causing pain not just in body – mind too. But it is really tricky to use and make work and keep working. 1/4 of a 50 mg. Is enough to do it, for me. And it has to be rotated on and off of. If I take it too many days in a row, it quits working. I don’t use it as much now. But I used to rotate off and on to keep a low dose working. Then stay off for a month (or more) and back on. Now I just take it occasionally. When needed. Calms my autonomic nervous system and helps my POTS. (It will however cause brain fog.) Bentyl is a very mild muscle relaxer. Normally used for IBS. I found this to help FMS pain when in combo with Tramadol. It will cause depression though as its a suppressant. So I couldn’t take it often either. But taken occasionally when needed, is a good help. I tried all sorts of herbs to tweak those same receptors with some help (to a degree), but not as well as that combo. (I stress, this could not be used continuously. It would stop working. I refused to up dosages and risk addiction.)

I only mention this as I relate so much to Whitney with his progression in my own journey. I did not try Abilify. But could not take Ativan. (It was too strong for me. I never tried to break it down smaller.) But my medicines and his do similar things with similar properties. Has to be a connection here.

I’m glad you mention Marco and his talking of glutamate. He and I used to have great conversations on that. I feel that is a key issue. Been a part of my hypothesis. (And Dejurgen has been able to expand on it with science to back it up, and he has found connections as to WHY.) Sure would like to talk to Marco again. Haven’t seen him on the forum lately. (Marco, PM if you read this.)

Lots of my issues got worse when I had a combo of ruptured appendix, ulcerative colitis and pneumonia all at the same time. The colitis was so bad, we had to kill off all the bacteria in my body with chemo. So definite gut issues….to this day. MCAS plays a huge role with me. (And I believe more people. But they don’t realize it.) Again gut comes into play here, because what we eat can affect that strongly. Histamine helps regulate the immune system. We need it. We just don’t need too much of it. Getting histamine receptors to work better, for me, has been a big help. (I don’t block histamine receptors. I manipulate them.) Still don’t have it perfect, but a work in progress. Dejurgen and I both have found it to be a key part with us.

Thanks for the overview Cort. I think if we can find patterns that will point us to more clues. I see patterns between Whitney and myself. I’m also very sensitive to near everything.

My stomach issues got worse after my appendix burst. I’ve always wondered why that is. I didn’t notice my other issues/overall symptoms affected by it one way or another.

Hi Urrrgh, i believe they (someone) decided the appendix is the storage in the body for various bacteria that are dispensed for replenishment to the microbiome when general stocks are negated or depleted. Like a little sac of useful bacteria held in reserve. Dispensed on requirement. So having it burst would seemingly do some rearranging of the gut bacteria.

“So having it burst would seemingly do some rearranging of the gut bacteria.”

And introduce plenty and plenty of bacteria in your abdomen between your organs where they do NOT belong. A rupturing appendix is almost as bad as doing abdominal surgery and adding a few turds in it before sewing the wound close. When untreated, appendix rupture is often lethal.

And, my appendix rupture went untreated for 2 years. And I had all that mess inside and damaged organs and adhesions from all of it. The antibiotics they say “saved me” but messed my intestines up. And then pneumonia on top of it and me with Hypogammaglobulinemia. (Then chemo to kill off all the bacteria in my body both good and bad. As it was the worst case of colitis the doc said he had ever seen in 30 years of his career.. and it should had killed me in 2 days, he said.) So any of the 3 should had killed me. But, I’m still alive to tell the story.

WOW…..you must have gone on one hellova ride….me too

Ughhh…..two things that have helped me is specifically addressing mitochondrial fatigue. MitoSynergy and K-PAX Immune Support. If you’re interested you may search those products, do your due diligence and reading of course.

Curious about Stellate Ganglion Block (SGB). It makes sense. SCIG flipped my immune system enough that I’ve had significant improvement (can ride an exercise bike for 50 minutes with tension). But considering SGB to more directly calm ANS/vagus nerve.

I’m interested in the Sphenopalatine ganglion bloc and the stellate ganglion block. I’ve been mentioning it at pain management. At my last pain management while they were giving me occipital nerve blocks I mentioned it again and Dr. said why, and I ran down list of my symptoms and she said they treat the sympathetic nerve blocks much more seriously and with caution (vs the occipital and previous trigeminal nerve blocks I’ve had so far) and she said they do them, but to make an appointment so we can discuss more. So I don’t know what they will ultimately decide on this. Have you discussed the stellate block with your Dr. yet?

Interestingly I don’t believe I have had a cold since I’ve had ME/CFS. If so, it was so mild I didn’t notice. That’s 46+ years without getting a cold. I’ve only had a virus once or maybe twice, after coming down with ME/CFS. I did, however, have Covid-19 in 2020. Usually when I am around some one who has a virus, I don’t get sick, but I do experience PEM for a few days afterward. (It took me a long time to figure out why I was experiencing PEM when I seeminly did nothing to cause it.) I do get bacterial infections from time to time. We’re all quite different, aren’t we? It’s like we get ME/CFS and it adapts to each of us differently, except for a few core symptoms.

I am the same as Juanita in that I’ve had ME for 30 years, yet can’t remember getting a cold in all of that time, or any other type of virus. My onset of ME followed what felt like a flu-like virus that made me very sick for about three days, then kept relapsing several times over a period of several months. My nose runs constantly and I do cough here and there, but I’m guessing that’s a mast cell problem. I have gotten a lot of bacterial infections, including MRSA and Lyme disease that went chronic 6 years ago. The Lyme disease attacked my heart and joints, the ME attacked my muscles. Both are equally fatiguing and brain fog inducing.

I had a cold maybe twice since on set. That’s over 31 years. i do get stomach bugs occasionally. I get the flu vaccine now because the flu has made me incapacitated at times. I was told to avoid vaccines but now I’m much older and can’t handle the flu.

I started hearing about Covid-19 Long Haul in Dec 2020. I would hear how it was effecting people and thought it sounds like CFS/Fibromyalgia. By January 2021 I googled the Long Haulers and CFS/fibromyalgia and found a Harvard related article connecting them. I always wanted there to be a magic pill and I hope to God this is the beginning to the end. I don’t care how long that takes I just want science to figure out what needs to happen so others don’t have to go through what I have experienced.

AriKat, I’m with you, 100%. I’ve been making the same observations and am hopeful that research with COVID long-haulers will be helpful with other chronic conditions — and vice versa.

I also have weird experiences with colds. There was a missing option on the poll. Before I “got sick” I got maybe (if) one cold a year in February, and it didn’t slow me down at all. After I became ill, I never got colds, never “caught” anything for the worst/beginning years. When I started to recover from severe to moderate, I got a cold, and I was overjoyed, because it felt so great. I told my doctor at the time how wonderful I felt that I had a cold, and the doc looked perplexed and uninterested. I thought it was a great clue. To this day, I look forward to getting a cold because it feels so good. As if my immune system is working at that time, and the rest of the time it’s subpar. FYI – After 15 years with “ME/CFS”, I was diagnosed with Lyme disease and I have been treating it now for several years and now I”m working part-time.

Check for low body temperature. Illness that raises it could make one feel better.

I just wanted to add how I caught a virus in 1990 and couldn’t get better. Then positive mono test…..

I started having Candida problems a few years before I received the ME/CFS, Fibromyalgia diagnosis. I was told I have both. I’m wondering if that’s possible and if others have been diagnosed with both.

I too had/have candida, white furry tounge BUT we’ve been lied to about candida also….many people , before all this hit the internet 30+years ago were told they have candida but ended up with lyme disease or other diseases

Whitney, you must be one of the people worst affected by ME/CFS on the planet. That makes you one of the people worst affected by chronic illness on the planet.

At the same time, you show a courage to carry your burden and life with such grace. The depth of your burden is hard for me to imagine. Slowly crawling back, I can even no longer fully comprehend the depths of my own illness when it was at its worst. I remember it, I know what that period was, I can describe it yet I lack the intensity of reliving these memories to fully comprehend it any longer.

Where you are and have been, I could not imagine at my worst. To learn and deal with it when energy is so short and the smallest effort hurts and depletes, that is only possible for the true great minds of this world. Whitney, you are a monument, a beacon of light and hope for so many of us. If you can keep fighting, we can! Thanks for keep fighting, thanks for keep hope alive!

One day we hope to return you the favor, by being able to provide better understanding on how we slowly were able to break free from the chains of severe disease. Project breaking ME, slowly going forward around the globe.

On a practical note, I see you can slowly start to stand and take a shower. Did you try and do so while sitting on a shower bench? Many patients with ME/CFS do better with a shower bench.

Also, did you try and change the temperature of the shower water a bit? I experience that a bit too hot shower water can be very pro inflammatory and exhausting. Dropping the water temperature, even for a few seconds, by a few degrees when showering on the spine helps calm my inflammation and increase energy production remarkably with me. Be careful and go low and slow if you try. Everything can fire back. If it worked, it would be sad to not know this little trick however.

I had to think about it as I see reason for it to be able to calm down the glutamate pathways. It’s an idea called the spinal escalator that Issie and I have been working around.

We wish you the very best, warrior!

I had an exposure to asphalt and started going down hill fast. My episodes always begin with a toxic exposure. I was told I was losing atp and that is why I was so weak I could now barely walk or think. My dr put me on ten tablets of atp A day and I bought an infrared light for 100 dollars. It took mr four months to recover. I can now do housecleaning and cook. My right leg has muscle pain however that I cannot get rid of but I can walk

Why don’t we feel calm? Anybody?

Stress hormones do more then just annoy us, makes us sick or provide us with a short term boost in energy production.

We have high levels of stress hormones so often, that this “short term” increase in energy production when stress hormones are increased is becoming the new normal. It hence can help us to produce the bare minimum amount of energy we need where without it we risk to fall beyond producing viable minimum levels of energy.

Actually, one of my first improvements was due to me using a drug producing bat crazy and rather dangerous high levels of (nor-)adrenaline in combination with doing basic circulation exercises. Neither of them apart worked, but the combo provided one of my first breaks from the worst of this illness. I can’t advise this approach at all, as my heart rates went near out of control at times. It was too risky an approach that could have gone wrong, permanently wrong.

Luckily, it didn’t and somehow provided me with enough spare energy to heal. Part of the challenge was to not use that energy into any action physical or mental while the serotonin syndrome the drug provided could have made me suicidal and the very high adrenaline levels have driven me to action. Actually, I felt a massive urge to jump out of my bed and run through walls at more then a few moments. So, I am very sure this is not a safe nor sane approach and have been working on better and safer ones ever since.

Do you think that our adrenaline rushes are effectively epi pens, our way of dampening down potentially close flirtations with anaphylaxis from mast cell activation?

@Oliver: I couldn’t say that. I don’t know if we have high enough levels of it to be meaningful in preventing anaphylaxis. I very much doubt we up our levels as much as an epi pen can do, but our bodies possibly intervening earlier might reduce the need for such strong interventions.

Let me rather tell a repeated experience of mine. It happened the first time years in ME when I was having a bad spell of it.

I was always high on stress hormones since having ME. Then one day, it felt so much like I “ran out” of them. I couldn’t get angry, even if I tried (I tried to recall myself things that easily upset me for the sake of exploring what happened with me, I couldn’t get anywhere close to get angry). I couldn’t worry nor fear, even if the situation I was in quickly turned to life threatening. There was zero anxiety.

What was so life threatening? I had that day / night all of the sudden (and going hand in hand with the drop in stress hormones) no longer the strength nor endurance to move my chest in any meaningful way to breathe anywhere close to normal levels. I have good body awareness and was very aware that my chest was barely moving, that there was barely any air flowing in and out of my lungs. My breathing capacity had sunk many times below its normal up to the point that it could be easily mistaken for me to just try and hold my breath for a very very long time.

Nor-adrenaline and adrenaline made from it both do similar things: they divert blood and energy to the most essential organs. That includes the skeletal muscles and those are needed to move your chest in order to breathe. Back then, I had zero control over my diaphragm so I couldn’t just do belly breathing to make up for very poor chest movement. Also, both are bronchodilators. That means that they open up the small lung pockets and make breathing a lot more efficient. And both divert blood, oxygen and energy to the brain that is needed to perform and coordinate the muscle movements both voluntarily and involuntarily well. So, a stronger or weaker brain can impact how much we can move our chest muscle in order to breathe well.

I have a history of breathing problems. Remove those stress hormones, and breathing can and has dropped to abysmal low levels with me in the past. I made it through that first night by weeding out all thoughts but one: breathe in breathe out breathe in breathe out on a slow pace to try and support breathing and not waste any bit of energy on thoughts of no avail at that time like “will I make it through the night and if so how much damage will remain”. I felt I could not afford to give such unproductive thoughts even a few seconds of attention over that night.

It happened more then once since, but then I was somewhat better prepared. I am BTW one of few people that sleep better with coffee too. It too diverts blood and energy to the brain and helps with better breathing.

As to mast cell trouble: long term near chronic increases in (nor-)adrenaline levels has a side effect: it prioritizes the “urgent organs” over the non urgent organs, taking away blood flow and energy production from the digestive track leaving it in a poor state. That in turn can increase sensitivity of the gut a lot and… …create gut mast cell trouble…

Why didn’t Whitney use Ativan on a more regular basis to maintain or regain a measure of functionality?

Lorazepam (Ativan) is not a long-term solution because of nasty dependency issues, i.e. it is addictive and if used regulary associated with many side effects:

https://americanaddictioncenters.org/ativan-treatment/long-term

I have been taking a low dose of Klonopin for at least 10 years, similar to Ativan with same dependency issues. It is the only medication that helps me with the fight/flight response. I’ve not had to increase the dose and it is worth it to me despite risks.

This is an extremely helpful account, thank you Whitney, and thank your Cort!

What can we learn from these experiences?

1

The underlying pathology of ME/CFS must be located at the most basic biological level. ME/CFS not only affects all and any of the “metazoan” homeostatic functions of the human body (like the inborn immune system, inflammation management, arousal and vigilance, sleep, temperature regulation, stress response, locomotion and digestion), but also the “limbic” and higher mammalian functions including the reward system, mood regulation, cognition, memory and word processing.

2

ME/CFS is very special in the kingdom of diseases. In spite of its severe clinical ramifications it does not appear to be tissue- or cell-destructive in nature, which clearly sets it apart from degenerative, neoplastic or most autoimmune diseases (which is not to say that complications of ME/CFS can be of cell-destructive nature). As a matter of fact, if tomorrow a cure for ME/CFS was found, it can be expected that the vast majority of ME/CFS patients would rise out of their misery like phenix from the ashes.

I see this as evidence that the pathology of ME/CFS plays on a deep regulatory level. (Several aspects of the disease make one wonder if this level may be part of our biological “emergency” repertoire, that for some reason have become “hijacked” at the onset of ME/CFS and from then on has remained perpetually activated – an “immunological locked-in syndrome” of sorts. Here I think that Whitney´s father is right on track with his work on the IDO “trap”).

3

ME/CFS affects completely disparate physiological processes. It is a “dauer state” and it is “sustained arousal” – at the same time. It is vagal dysfunction and sympathetic dysfunction – at the same time. It is adrenergic stimulation and adrenergic failure – at the same time. Clearly, ME/CFS does not fit into any single regulatory biological unit. This is why we have so many hypotheses as to which brain nucleus, which receptor system or which transmitter system may “explain ME/CFS”. We have theories about a broken locus coeruleus, amygdala, paraventricular nucleus, suprachiasmatic nucleus, even a “fatigue nucleus” has been suggested as “the broken piece”. Likewise, we have theories about dysfunctions in the dopaminergic transmission, the serotoninergic transmission, the glutaminergic transmission, or the adrenergic transmission. Indeed, ALL these explanations make physiological sense and none of them can be refuted. Yet, the obvious disparity of these explanations clearly demonstrates that these are only pieces of a much wider picture.

4

Which picture? Here I think we have to get back to very basic physiology. From this vantage point there is only one tissue which can explain the overarching pathological and clinical presentation of ME/CFS: the astroglial and/or microglial matrix of the CNS. In fact, this is the only biological unit which can explain the dysfunctional state of the deep rooted, archaic regulatory circuits affected in ME/CFS.

Indeed, the astroglial compartment is the only tissue which is SIMULTANEOUSLY involved in the regulation of brain perfusion, of the blood-brain-barrier, of neuroinflammation and the innate immune system. It is the only cellular compartment which regulates the basic circuits involved in autonomous functioning and the stress response. It is also the only tissue that at the same time influences mood, motor functions, sensory gating, memory and cognition. And it is a functional tissue that links ALL transmitter systems, ALL receptor systems and ALL brain nuclei implicated in the pathology of ME/CFS. And – by the way – it is the only tissue that may explain why “mechanical” or neuro-orthopedic cases result in the same clinical picture as the primary immunological cases of ME/CFS. Also, it is a tissue with a unique property very relevant to ME/CFS: astrocytes and microcytes are unique among all other cellular compartments in their flexible response to stress – they are able to change their functional state profoundly in response to activation: following pro-inflammatory stimulation these cells remain in an activated state and thereby become hyperresponsive to any form of subsequent stimulation. This ability of forming “stress memories” of sorts may explain the waxing and waning picture of ME/CFS and its unique clinical feature of post-exertional malaise. Not to forget that the activation of astroglia happens in cooperation with mast cells (which are now indeed being understood as “partners in crime” of astrocytes). And, not to forget, that astrocytes are “IDO competent cells”.

5

Just to finish the picture. Neuroscience has advanced greatly in the last several years in its understanding of how the brain works. Neuroscientists used to try to understand brain function and dysfunction starting from topographical units (brain areas or brain nuclei) to which they assigned specific functions. A similar approach was later pursued with neurotransmitters and their receptors – a certain disease, like depression, was then coined as a disease in which a certain transmitter (or receptor) system was dysfunctional. However, this view has been expanded considerably. Neuroscience now understands the brain as a functional matrix of interconnected pathways forming multiple large-scale networks (called resting-state networks, like for instance the default mode network, for a review, see: https://www.nature.com/articles/nrn3801). The analysis of the functional connectivity of these networks has identified sets of regions that can be seen as essential “hubs” for efficient neuronal signaling and communication. While these hubs are embedded in specific anatomical locations, they have functional roles across a wide range of cognitive and affective tasks and are part of a multitude of transmitter systems. Pathology may arise from dysfunction or disconnection within these brain hubs through which they lose their local connectedness and their short path length (indicative of global integration). It has been suggested that such “connectivity hub overload” or “hub failure” may be a potential final common pathway of several neurological diseases, including anxiety, posttraumatic stress disorder, anorexia nervosa or depression.

For me, it is plausible that similar changes in the brain “connectome” may underly ME/CFS (where functional connectivity issues have also been identified in functional MRI data, see Leigh Barnden´s work, for instance). Not surprisingly (at least for me) there is evidence that astrocytes may be the decisive players in the neuronal connectome of the brain. Indeed, their inflammation-induced dysfunction may be at the beginning of connectivity hub failure.

6

So I think there is a lot of evidence that at the very core of ME/CFS we may be dealing with a complex form of neuroinflammation involving the astroglial compartment and the innate immune system (which is functionally inseparable from microglia and astroglia). This may also explain the few successful therapies in ME/CFS – as a matter of fact, we only have a handful of therapies shown to work on a reasonable evidence level: staphylococcal vaccine (tunes down the innate immune system), Rintatolimod/Ampligen – does the same (if through different toll like receptors), and possibly now Aripiprazole.

As of yet, the mode of action of Aripiprazole needs to be better defined, yet, there are indications that it may reduce proinflammatory cytokine levels by inhibiting Src kinase activity in macrophages ((https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29241811/)) and may even activate stem cells in the CNS, which may be able to produce new neurons, astrocytes, and oligodendrocytes. ((https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24389877/)). Moreover, it has been shown that Aripiprazole may als reduce glutamate excitotoxicity by suppressing astroglial excitatory amino acid transporter genes. ((https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19524631/))

And what about lorazepam, which seems to have had significant effects for Whitney? Its sister drug diazepam is a potent inhibitor of microglial activation ((https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/14678758/))

So this has become a long comment. But after many years of extensively studying the ME/CFS literature as a scientist there is no doubt for me that this is

a) a CNS disease (ALL other manifestations including cardiovascular dysfunction, muscular and mitchondrial dysfunction can be logically explained as secondary to a central (CNS) regulatory dysfunction) and

b) that the dysfunctional matrix of this disease is a pathologically primed astroglial compartment.

I therefore do hope that the research opportunities now opening up will have a more rigorous focus on neuroinflammation in the connectome of the brain. For me this is the broken hub in which the many dysfunctional spokes of ME/CFS meet.

P.S. I am currently working on a comprehensive review of this “deep unifying theory of ME/CFS”. It will be available as a fully referenced preprint working paper shortly. Whoever is interested may find my name in the www and contact me.

First, I agree that this disease feels “ancient”, like my body is re-battling a battle that my ancestors won long, long, long ago. That’s not very scientific, but I agree that this disease is embedded deeply in our very basic biology.

Second, how have you not ruled out the Kupffer cells as ground zero? If they are dysfunctional (either due to be overwhelmed, depleted, or otherwise incapable of their function), then might they be leaving the astroglial cells and other macrophages dealing with a contaminant (“something in the blood”) that should have been removed by the Kupffer cells? Or the Kupffer cells are stuck in inflammation mode and their SOS cellular signal actually is the “something in the blood” that is setting off the other macrophages and similar cells to go on alert? (“Something in the blood” refers to the experiments showing that ME/CFS blood has been shown to flip healthy cell cultures to a disease state: https://mecfsresearchreview.me/2019/04/25/something-in-the-blood/). The “something in the blood experiments” must tie in to any unifying theory.

The Kupffer cells activate for viral infection, toxins, and nerve damage, which are all known to be triggers for the illness.