Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is a pretty big deal. The most common gut disorder, IBS, costs the U.S. economy about $1 billion a year and occurs in a considerable number of people with chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS) and/or fibromyalgia (FM).

It, ME/CFS and FM, have long been considered “functional” diseases e.g., diseases that can cause substantial reductions in functionality but without an apparent cause. Gut imaging studies that found nice, healthy-looking guts in the midst of considerable pain have left researchers puzzled – with some searching for a psychological cause.

The same scenario, of course, has been applied to ME/CFS, FM, and POTS – three “invisible” diseases without obvious structural abnormalities that are more likely to be diagnosed in women.

IBS, like ME/CFS and FM is considered a “functional disease”; i.e. a disease without a known cause which impairs functioning.

That psychological idea for IBS has never held much water. While it’s true that calming therapies can help reduce symptoms, the same is probably true for many conditions. The fact that some people can avoid or even eliminate their symptoms by avoiding some foods (carbohydrate-rich, gluten-containing, dairy, citrus, beans, cabbage/broccoli, and similar vegetables) or by going diets like the FODMAPS diet has suggested that a food connection is present.

We know that IBS is a hypersensitivity condition because inserting a balloon into the colon and slowly blowing it up causes pain in people with IBS but not in healthy controls. Why the pain is there has been unclear. A paper, “Local immune response to food antigens drives meal-induced abdominal pain“, that popped up in the Nature journal earlier this year may provide answers, – not just for IBS but for other “functional syndromes” as well.

It offers an explanation for several of the mysteries that have permeated the IBS, ME/CFS, FM, and other fields. It shows how an infection can lay the groundwork for a chronic disease, it demonstrates why standard measures of inflammation have never revealed much, it shows how easily the causes of diseases like these can be hidden, and it shows how the nerves come into play. Plus, it validates something ME/CFS experts consider to be a hot topic (mast cell activation syndrome (MCAS) but which the medical research field has yet to embrace.

Not bad!

The Infection Connection

The authors – all 45 of them (!) (from Belgium, Germany, Canada, and the U.S.) – started off by noting that about 20% of IBS patients report a gut infection sparked their illness, making IBS, at least in part, a post-infectious disorder.

They suspected that IBS is a food-triggered antigenic driven event; i.e. that certain foods are sparking an immune reaction in the gut. First, they infected one group of mice with a pathogen (Citrobacter rodentium) while exposing them to a known antigen (ovalbumin (OVA)); i.e. something they knew would also spark an immune response. Another group of mice were exposed to the antigen but not to the pathogen.

The mice which had been infected and exposed to the antigen cleared the infection but then developed an IBS-like condition; i.e. they experienced diarrhea, increased fecal water content, increased transit times, increased gut permeability, gut muscle contractions, and hypersensitive response (pain) in the gut. Antibodies to the antigen also showed up.

The infection was the key! Without the infection, the immune system did not become activated and IBS did not occur.

Re-exposing the mice to the antigen later resulted in another period of prolonged gut hypersensitivity. Exposing the mice to other antigens, interestingly, did not evoke an extended period of gut hypersensitivity. This indicated that the immune systems of the mice had been sensitized only to the antigen which had been introduced when they were fighting off the infection.

None of the above happened in the mice that had not been exposed to a pathogen. In an interview with Jane Brody of the New York Times, Dr. Marc Rothenberg explained what appears to have happened.

The infection temporarily disturbed the protective layer of cells lining the bowel that prevents allergy-inducing proteins from being absorbed. Losing that barrier – even for a short time – sensitized the immune system to those proteins – causing it to react to those foods.

Treating the mice with a monoclonal antibody that latched onto the suspect antibody stopped the whole thing in its tracks; i.e. it appeared that an antibody-triggered immune reaction was behind the whole thing. They explained it like this.

“Together, these data indicate that a gastrointestinal bacterial infection can break oral tolerance to a dietary antigen and result in an adaptive immune response towards food antigens, leading to increased permeability and abnormal pain signaling upon re-exposure to the antigen.”

Over a series of studies, they dug deeper and deeper. Exposing the mice to a gut pathogen and an antigen at the same time caused dramatic shifts in the mouse gut flora – but as neither antibiotic use nor the shift in the flora (at least at a macroscopic level) produced the gut hypersensitivity problem, they discarded an altered gut flora as a cause of the problem. (This may not be a particularly solid finding as the authors determined this using the two main genera driving the bacterial shift and did not take other bacteria into account.)

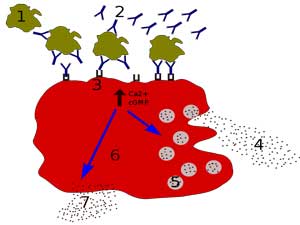

Next, they turned to inflammation and mast cell activation. Although the low-grade inflammation found during the acute phase of the illness resolved itself an intriguing uptick in the expression of a mast-cell gene (tryptase α/β-1 gene (Tpsab1)) showed up. That suggested that the mast cells had become sensitized – and were just waiting for an opportunity to activate.

Next, they linked the increased gene expression to the increased production of the main mast cell mediator – histamine. That indicated that the mast cells had degranulated and released their immune mediators. Validation of the mast cell connection occurred when treatment with the mast cell stabilizer doxantrazole turned off the gut hypersensitivity problems completely.

The B-cell connection was validated when eliminating B and plasma cells also reduced the levels of the pathogen-specific antibodies and prevented the development of gut hypersensitivity. It appeared that the original antibody response that had popped up during the infection/antigen overload was driving the mast cell response.

More evidence that IBS is, at least in some people, a mast cell-induced disorder was forthcoming. Studies showed that histamine-containing fluids from people with IBS and colonic liquids from the mice were able to produce pain hypersensitivity (central sensitivity). Adding a different histamine antagonist called pyrilamine once again turned off the pain.

The researchers have even identified ion channels (TRPV1) in the sensory nerves that get turned on during this process. They’ve also shown that other pathogens can – in the presence of an antigen – reproduce the whole process; i.e. the infection/antigen/antibody/mast cell connection seems broad indeed.

(Note that an infection is not necessarily required to start this process – anything that wipes out that protective gut lining could do that. Although the authors discarded an altered gut flora as a cause, their gut flora analysis was rather primitive. The inflammation-promoting and gut lining damaging gut flora found in ME/CFS could presumably do the same damage as an infection, and probiotics and other gut flora influencing treatments can help.)

Next, they looked at indicators of increased mast cell activity in people with IBS. Tryptase activity was higher both under baseline conditions and when exposed to 4 common allergens (soy, wheat, gluten, and histamine). AEBSF – a broad-spectrum serine protease inhibitor – also completely stopped the trypsin-like activity.

Activated mast cells (red dots) found close to the nerves were responsible for the gut pain. (From Mikhael Haggstrom – Wikimedia Commons)

Some doctors test for MCAS by assessing how many mast cells are found in gut biopsies but this group didn’t find an increase in the total number of mast cells. Instead, people with IBS had more IGE+ mast cells close to their nerve fibers. In fact, the closer they were to the nerve fibers, the more pain the IBS patients were in – suggesting that this entire reaction is very localized (and quite hidden from sight).

The fact that the antibodies are only found in colonic tissues – not in the circulation – underscores that this is not a typical allergic process that occurs systemically. The authors noted that a similar process has been found in allergic rhinitis and chronic rhinosinusitis.

They proposed that IBS, at least in some patients, is at one end of a spectrum of food-induced disorders, all of which, they believe, are driven by mast cell activation. Systemic food allergy is at the other. The lead author, Professor Guy Boeckxstaens, stated:

“At one end of the spectrum, the immune response to a food antigen is very local, as in IBS. At the other end of the spectrum is food allergy, comprising a generalized condition of severe mast cell activation, with an impact on breathing, blood pressure, and so on.”

They also proposed that people who are more genetically inclined to have more allergic reactions (allergic rhinitis, asthma, allergic eczema) are probably more likely to develop IBS.

Impressive Paper!

It’s easy to see why Nature – perhaps the most read scientific journal in the world – was happy to publish this work. It reports on a very methodical, step-by-step process that may have tracked down at least one of the sources of a very mysterious disease. Its main shortcoming concerns the small number of humans in the human study – something which is surely being remedied now.

The model helps explain why IBS has been such a mystery. The infection sweeps through, exposing the gut to elements that it reacts to – setting up a long-term immune reaction. The immune reaction is quite localized, however – it only sparks a reaction in the gut itself (making blood tests iffy) and then, and perhaps most importantly, only affects the nerves. That makes it hidden.

All the time the nerves are going bananas the tissue apparently looks perfectly healthy. This is, if memory serves, exactly the process that mast cell proponents have proposed is happening. All you need to bake this pie is to have activated mast cells close enough to the nerves to make them scream.

Professor Guy Boeckxstaens, the lead author of the paper, summed up how this work should change doctors’ ideas about IBS.

“Very often these patients are not taken seriously by physicians, and the lack of an allergic response is used as an argument that this is all in the mind, and that they don’t have a problem with their gut physiology. With these new insights, we provide further evidence that we are dealing with a real disease.”

A Fit for ME/CFS/FM and Long COVID?

Could activated mast cells be tweaking the nerves in fibromyalgia and ME/CFS?

Could this general model help explain ME/CFS, FM, POTS, and long COVID? Might the endothelial cells lining the blood vessels in ME/CFS/FM and long COVID present a similar scenario? A different pathogen disrupting the protective layer lining another important roadway in the body? Time will tell but one thing is for sure – mast cell activation syndrome (MCAS) – long ignored by the traditional research community – has just been shown to provide a plausible answer for a medical mystery.

Could activated mast cells be tweaking the nerves in FM? Something is doing that, after all, and that something has not been identified. Nor does that something, similar to IBS, appear to be producing much of a systemic reaction or causing any tissue swelling or damage. Instead, in its hidden way it’s going straight for the nerves. It’ll be interesting to see if this IBS study sparks studies that start looking for mast cell activation in FM.

At the 2018 Dysautonomia Internationa Conference Brent, MD. asserted that the gut problems in POTS were caused by mast cell activation syndrome (MCAS) and described how a panoply of treatments returned a very ill POTS/MCAS/IBS patient to health.

The Gist

Could the brains mast cells be causing ME/CFS?

- Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) has long been considered a “functional disease”; i.e. a disease that substantially impairs functioning – but which doesn’t have a clear cause. The mystery is deepened by the fact that while people with IBS often experience severe gut pain, bloating, etc. the guts appear pink and healthy.

- A recent publication is one of the most prestigious scientific journals – Nature – may change all that. Through years of work several research teams that have slowly picked away at IBS findings using rodent studies and most recently human ones have come to a realization – IBS, they believe, is a mast cell disorder.

- First, an infection wipes out the protective layer lining the gut – exposing it to food proteins or antigens it usually doesn’t encounter. The immune system leaps to the rescue – attacking the proteins – and causing gut cramping (the muscles contracting in response to the antigens), bloating, constipation, etc.

- The infection clears – leaving the mast cells activated and ready to pounce once the suspect food is introduced again. Importantly, only the food proteins introduced when the gut lining was damaged are able to spark an immune reaction. Even after the gut lining is restored, though, the immune system still senses an invader is present and rises to the attack. It’s that immune response that’s causing IBS.

- Interestingly, mast cell numbers did not seem to be increased. Instead, the mast cell location made the difference. Mast cells found near the nerves provoked the reaction while mast cells more distant from the nerves did not.

- This indicated that the mast cell activation is VERY localized and explains why tests of mast cell activation or inflammation often don’t explain much. The authors believe that the mast cell activation in IBS is akin to that found in food allergies except that food allergies provoke a systemic immune response while the mast cells in IBS provoke a very localized mast cell response – leaving them mostly hidden from sight.

- The mast cell activation is the end product of the immune response. The process is begun, however, when B-cells produce antibodies to the offensive proteins of the foods.

- The paper’s weak point was the small sample size used in the human studies. That needs to be rectified but the evidence leading up to the human studies seemed overwhelming. Step by step, the researchers have produced an impressive body of research that appears to have tracked down a cause of IBS that could explain much.

- Of course, if immune and mast cell activation explains IBS could it also explain its sister diseases like ME/CFS, fibromyalgia, and POTS? In their lack of structural damage and overt physical findings, the diseases all resemble each other. Each can be triggered by an infection and each seems likely to be immune-mediated but evidence of significant inflammation (except perhaps in the brain) is lacking. Could mast cells be producing very localized reactions that are tweaking the nerves and escaping detection in these diseases as well? (VanElzakker has proposed that small, localized infections affecting the vagus nerve may be being missed in ME/CFS).

- The authors of the Nature paper suggested that antihistamines and drugs that reach further upstream of the mast cell activation may be helpful and cited some. Other, hopefully, more effective mast cell inhibiting drugs are in the final stages of the drug approval process and could provide more help for IBS and perhaps for ME/CFS and FM patients as well.

- Some mast cell treatments are described in the blog – check the treatment section for those.

Dr. Klimas has called it one the most interesting immune diseases going.

Treatment

A larger trial using antihistamines is underway but the lead author believes antihistamines present just the beginning of a potentially effective treatment regimen. Professor Guy Boeckxstaens hoped the studies will spark the development of more effective mast cell treatments.

“But knowing the mechanism that leads to mast cell activation is crucial, and will lead to novel therapies for these patients. Mast cells release many more compounds and mediators than just histamine, so if you can block the activation of these cells, I believe you will have a much more efficient therapy.”

The authors suggested using mast cell inhibitors like the H1R-antagonist ebastine which target the upstream mechanisms behind the mast cell activation should be more effective. Ebastine is a non-sedating HI antihistamine that studies show can help IBS. The authors also plugged omalizumab, a monoclonal antibody against IgE26, which in two case reports completely resolved severe cases of IBS, as well as treatments like IgE neutralization, and drugs that can inhibit spleen tyrosine kinase.

In an interview, Rothenberg also noted that new mast cell inhibiting drugs are now in the very last stage of approval (Phase 3 trials).

Check out how two informed MD’s treat MCAS.

Dr. Chheda on Treating MCAS

High doses of antihistamines are, of course, one possibility for this situation. Dr. Bela Chheda explained how she diagnosed and treated MCAS a couple of years ago.

Citing their inaccuracy, she doesn’t run 24-hour urine tests but does run a mast cell panel (tryptase, chromogranin, histamine, prostaglandins, IgE). (The tests leave something to be desired – using them to form a diagnosis is rather problematic.)

- Tryptase – a small percentage of people have elevated tryptase. When tryptase levels are elevated, they’re usually borderline elevated (13-20).

- Chromogranin – another small percentage of patients have high chromogranin. (She noted that low stomach acid can also cause elevated chromogranin).

- Prostaglandins – The two main MCAS markers she uses involve the prostaglandins. Prostaglandin D2 is the most helpful marker, but because it can have diurnal variations, it may take several tests to capture the elevation. F2 alpha – which is a breakdown product from other cells as well as mast cells – is moderately diagnostic.

- IgE is not diagnostic, but high IgE levels suggest that something may be going on with the mast cells.

Biopsies of the GI tract or from colonoscopies can provide another clue if they find high numbers of mast cells. If a patient already has a biopsy, she tries to get it stained and counted for mast cells. While it’s not clear yet what constitutes an abnormal number of mast cells, in her experience >30 is probably abnormal.

With the diagnostic testing lacking accuracy, often a trial of MCAS medication – which is usually well-tolerated – is called for.

Dr. Chheda referred to a recent patient with a classic case of ME/CFS who did not appear at first blush to have MCAS. An antihistamine trial told the tale, though; while neither 1-2 antihistamines a day made a difference, adding a third one did – it completely removed the patient’s anxiety!

Dr. Chheda suggests starting with non-sedating antihistamines such as Claritin or Allegra. (She doesn’t recommend patients trying more than 2 antihistamines at a time on their own without supervision.) She also can use an herbal mast cell stabilizer called Quercetin (500 mg twice a day) and ketotifen, a compounded antihistamine that is also a mast cell stabilizer,

If someone thinks they may have MCAS, Dr. Chheda recommends reading Dr. Afrin’s book “Never Bet Against Occam: Mast Cell Activation Disease and the Modern Epidemics of Chronic Illness and Medical Complexity” which contains more detailed information on treatments.

Dr. Carnahan on Treating MCAS

Dr. Jill Carnahan reports that the following over-the-counter drugs or supplements can block MCAS symptoms. If you experience MCAS symptoms and these make you feel better, it stands to reason that you may have MCAS. (Not responding to these treatments, on the other hand, does not mean that you don’t have MCAS.)

H1 blockers

- Diphenhydramine (Allergy Relief, Allermax, Banophen, Benadryl, Compoz Nighttime Sleep Aid, Nytol QuickCaps, PediaCare Children’s Allergy, Q-Dryl, QlearQuil Nightitme Allergy Relief, Simply Sleep, Sleepinal, Sominex, Tranquil, Twilite, Unisom Sleepgels Maximum Strength, Valu-Dryl, Vanamine PD, Z-Sleep, ZzzQuil and many others)

- Loratidine (Claritin, Claritin Liqui-Gels)

- Cetirizine (Zyrtec, All Day Allergy)

H2 Blockers

- Famotidine (Pepcid, Pepcid AC); Cimetidine (Tagamet, Tagamet HB); Ranitidine (Zantac)

Mast Cell Stabilizers

- Cromolyn, Ketotifen, Hyroxyurea

Natural anti-histamines and mast-cell stabilizers

- Ascorbic Acid, quercetin, Vitamin B6 (pyridoxal-5-phosphate), Omega-3 fatty acids (fish oil, krill oil), Alpha Lipoic Acid, N-acetylcysteine (NAC), Methylation donors (SAMe, B12, methyl-folate, riboflavin)

So interesting as always.

I’m curious to understand the role of B-cells better — was it just for induction or also for the ongoing maintenance of the gut hypersensitivity?

I’m also trying to get my head wrapped around whether the dysfunction following these “bad associative memory” situations must always be mast-cell mediated or if it’s more of an upstream B-cell type thing, which can drive various downstream “misfires”, e.g. mast cell, T-cell, etc. I have the work about T-cell exhaustion from Drs. Selin and Gil in mind too.

In my own case, I’ve addressed some histamine/mast cell issues and it seems to address ancillary symptoms (breathing, throat, eyes), with no impact on my core fatigue symptoms. That’s driven my recent thinking that histamine effects may be secondary (and perhaps driven by gut histamine, not mast cell histamine).

But that’s why I come here: to learn new evidence and new ideas!

From my admittedly limited understanding of this paper, it seems that the B-cell problems come first! I imagine they could do more than activate the mast cells. On the other hand, I wonder how effective our current mast cell treatment regimens really are and what better treatments might do.

There are some common issues that the medical community sometimes overlook. Oxalate toxicity and parasitic infections will cause mast cell activation.

Oxalate overload is more common than most people realize. Parasite infestation in humans is also common…even in “modern” western countries like America and Canada.

Thanks Cort. I wonder what has happened to Issie because mast cells and histamine was her favourite topic?

I think it is feasible that, for some, ME/CFS is a systemic inflammatory illness similar to asthma with inflammation and oedema at any epithelial surface in contact with allergens or microbes, including the gut, blood vessels, bladder, nose, lungs, etc. Systrom has found evidence of low blood volume and possible oedema in the microcapillaries in a subset of patients but I think these issues might extend beyond the capillaries.

You have previously posted about Travis Craddock’s finding of genetic defects in the mucus producing genes, meaning mucus layers might be too thin. There is also a possible overlap here with the Griffiths University work that found issues with calcium ion channels and the TRP channels in particular. These play a role in immune / mast cell control and thin mucus barriers and twitchy mast cells could be a bad combination.

I have had issues with allergies and asthma since my early childhood and ME/CFS came as a teen following an infection. New problems have surfaced with infections since that time and any sort of gut infection nearly invariably triggers a relapse but the inflammation associated with a bladder infection or similar can also take months to resolve. Prednisone helps, which implicates mast cell issues. Adopting a gluten free diet in the early 2000s bought me nearly 3 years of partial remission before I went downhill again, which also points to an allergic contribution.

I find that stress exacerbates my illness. Histamine raises adrenaline and adrenaline increases histamine, so there is a bit of a vicious circle there. I regularly experience an unusual wired, anxiety that affects my mental state but does not appear to stem from it. Adrenaline is a bit problematic for me.

wow debsw, i didnt know the adrenaline histamine thing. so grateful to all who post here in comments

Hi Sunie. Apologies, my memory failed me when I wrote my comment. It is histamine and estrogen that form a vicious circle. Adrenaline is actually released to counteract histamine. However, stress does cause mast cells to degranulate and dump histamine (in animal models at least). The process appears to involve upregulation of corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF) and CRF receptor dysfunction forms the basis of the Cortene theory.

Hi there, having followed (and tried!) most things this forum has had to offer in the last seven years of living with a diagnosis of ME/CFS, I needed to tell someone (ANYONE) that my symptoms have all but vanished with a daily antihistamine (Loratidine) and 16:8 intermittent fasting.

I had given up all hope of ever leading a normal life again, one without pain, exhaustion and tears – but I’ve found a tiny pill (£3.49 for 6 month supply on Amazon!) has totally transformed my life.

Gluten and dairy were cut out along the journey, as too were sugar, alcohol and caffeine.

Loratidine has literally changed my life from illness to wellness.

Wooow this Is fantastic.

What dosage do you take?

Have you tried liratidina only?

This is absolutely the case. I’ve been asking my doctor about this FOR YEARS. It’s been known about for 30/40 years. Janice jonela, more recently doctor afrin. There was a BBC segment on afrin about 5 years ago now. He said at the time that he thought 70/80 percent of cases of m.e. were mast cell cases.

So why is there no development really. I don’t get it.

Afrin says also that mast cells can also be out of control in the heart, which is not a good place to have mast cells degranulating wildly.

I came across this 15 years ago when I kept finding high dose vit c gave me relief.that got me started.

Again why is this taking so long??? The protocols suggested don’t work anymore for me and my quality of life is often desperate.

Mast cells seem to degranulate more in eds patients( I’m almost certain m.e. is an as yet undiagnosed form of eds, although Dr afrin says we can acquire eds through constant mast cell degranulation.

You’d think with all the super computers at Stanford something like this might be easy to work out.

From what I understand, Pfizer’s new antiviral was developed like that. As always it seems the will is not there.

That said I welcome this study obviously. It’s just so frustrating. I’ve literally been banging my head against a wall with doc over this fit years.

My anology for the endothelial vein part of the disorder would be.” Vascular asthma”..

I’m guessing many heart attack, strokes and high blood pressure cases are mast cell related

Excellent information from Cort as well as commenters.

I have asthma and tons of allergies too. These gut studies are something to pay attention to.

Another big post, sorry.

Apart from bleating on about the benefits of FMT, the only other ME/CFS “treatment” I’ve ever been on is Ketotifen. I was on that for about three years. It was prescribed by my immunologist (a professor of immunology who is also an allergist). He has a lot to do the with the Australian NCNED ME/CFS research team (i.e. Griffith University). I started on that drug just after I was diagnosed with ME/CFS (about 18 months after I got sick). At the time, I asked my immunologist if I had MCAS having found an article about it. The reply was “sort of”.

The Ketotifen helped me function, but I was still running in “sacrificial anode” mode. I was still working full time at that point. So the drug helped, but it is symptom relief/masking. This can come at the expense of allowing oneself to be finely attuned to pacing. I certainly progressed to become worse whilst on the drug. But the advice I had at the time was “don’t stop being active – you’ll get much worse”. I think this was meant to be advice about not becoming bed bound and ending up with orthostatic problems. But I took it as “keep working full time”. So I can’t blame Ketotifen for degrading my health. I was just pushing things beyond my envelope.

Stepping back to when I first got sick with ME/CFS, I used to get nonstop sinus infections. I subsequently used to smash the cold and flu tablets (paracetamol and pseudoephedrine). I’d consistently have so many of those that I’d have to stop taking them (having maxed out the recommended intake/duration). On one occasion, my sinuses were still incredibly painful at the end of a cold and flu packet. So I took an antihistamine in desperation (just old school Sudafed). Half an hour later my sinuses opened up and started to drain. That is when the light bulb went on that the sinuses were an allergic reaction. I didn’t need to pursue sinus surgery.

These allergic reactions were driven by certain foods. As well as the general allergic reactions induced by ammine containing foods, I also had weird allergic reactions to things like baked cheese cake. I went through the Royal Prince Albert Hospital elimination diet (FAILSAFE) with a dietician to get to the bottom of food reactions. So much chicken and maple syrup! After a while you get your confidence up and I took short cuts like eating a kilogram of peas in one sitting to rule out glutamate problems. I mention all of this because Ketotifen also helped with these allergic reactions. The dietician’s advice was that preloading with antihistamines before a problematic meal (e.g. most restaurant food) is much more effective than trying to manage the symptoms afterwards.

Ultimately though, an FMT was an order of magnitude more effective at stopping the food allergies. This specific ME/CFS symptom has “stayed fixed”, unlike brain fog and PEM where the symptom reduction has waned post FMT. So I eventually went off Ketotifen post FMT. I’m not that naturally inclined to pacing (psychologically speaking) so the masking of symptoms doesn’t do me any favours. I’m not trying to get on the FMT soap box again. Rather just trying to add some perspective that Ketotifen has benefits for ME/CFS, but wasn’t amazing, in my experience. It wasn’t that expensive, and it presented to me as having an extensive track record as a safe drug. I believe it is the go to drug for certain paediatric asthma management.

why didn’t you continue the FMT?

Sue,

FMT is in my experience a once off in terms of effectiveness. I had my microbiome scanned before and after my first FMT and that process confirmed it went from “broken” to “fixed”. And has stayed fixed. The ME/CFS symptom relief directly after the first FMT (within 24 hours) is in my experience, profound, and I believe a lot of that comes down to an athletic donor (butyrate related). I did do a subsequent follow up set of FMTs (both using the existing donor and new donors) and there wasn’t any profound change.

I know some folks use FMTs daily, but that has never seemed either necessary or beneficial to me. And quite frankly, the process involved is demanding and unpleasant enough so that if you aren’t getting any noticeable benefit, you’ll stop doing it.

So in summary, my advice about FMTs for ME/CFS is if you haven’t done it, and it is possible to pursue it safely with the help of your doctor (given whatever financial and/or medical practice limitations exist in your neck of the woods), do it.

Do you mean that the benefits you felt after FMT remain today? How much improvement did you have, overall, with the FMT’s? I have met several people who have 70-90% improvement with FMT’s. Most say the benefits were temporary but some are now continuing to do them for prolonged periods of time and getting more benefits and long lasted benefits. Also, sometimes changing donors helps a lot because it is very donor dependent.

Two people who have almost recovered with FMT’s are now selling FMT!

Do your tests show that you have no more inflammation in your gut?

Sue,

A lot of the GI benefit of the FMT remains to this day for me (like 70%). I’d say the food intolerances, bloating, “rebound hyperglycaemia/Somogyi” type effect (i.e. waking up at 0230 hot, sweating and upset rumbling guts) and other GI related symptoms improved by 70-90%. PEM – that doesn’t go away in my experience (mental or physical), although there might be some increasing of the envelope it takes to induce it. Sleep gets better with reduced GI weirdness. Reactive arthritis doesn’t change.

Repeated FMT hasn’t benefitted me. I did Prof Tom Borody’s protocol through a gastroenterologist who had trained with him – antibiotics then 10 days of FMT, starting with a colonoscopy FMT, then 9 days of enema FMT. My current gastro also has a PhD in genetics (Harvard). His understanding of FMT and ME/CFS is that research indicates it is most likely the Butyrate producing bacteria that are playing the lead role in the FMT impact.

My microbiome was originally scanned through the American Gut Project (which showed extensive dysbiosis) before my first FMT. My follow up microbiome scans have been through a local company that does the same type of thing commercially:

https://microba.com/microbiome-research/sequencing/

So it isn’t the symptomatic aspect (inflammation) that is being tested, it is the microbiome itself.

I had no idea you were in Australia. Is there any way we can exchange emails? I would love to talk to you further about your FMT experience. I am currently doing it DIY. My email: sueintoronto4@proton.me

Thanks!

Sue,

I emailed you. Hopefully that got through?

It is my understanding that FMT is very donor dependent. Have you tried several donors? May I ask how long you have had ME/CFS? I am wondering if the mitochondrial damage is just too great for some of us, for anything to produce significant changes. Dr. DeMeirleir told me years ago that due to my age and length of illness, I would likely not get more than 50% better even if I were to stumble upon a treatment that worked. (I will gladly take even 30% now!)

At any time during your FMT treatment or after, did you experience even a couple of days of close to normalcy or huge improvement? I experienced a transient, brief episodes sometimes.

Wow, this is interesting. I wish my science understanding was better to take more of it in! It does seem to press a lot of the right buttons for me though, as I am nearly 70 and have had IBS in various forms for much of my life.

Later on I developed other issues that are recognised as autoimmune but some are not seen as that, ie I do have diagnosed underactive thyroid, (25 years) but later on was also diagnosed with ME/CFS (15 years ago on that score)

I developed a an upper gut pain that was investigated and labelled as non-ulcer dyspepsia, and which would be triggered by certain foods/medicines – those mostly seen as acidic. I cold not tolerate LDN for example as I had this intense burning pain.

Inexplicably, though I have had that for about 10 years, it has now improved and I can eat some foods again as long as I am careful though a new worse pain began instead which mercifully can be quelled with a medication. I also had a kind of chronic sinus pain that would be triggered off by stress, fatigue, or by unknown factors. I had no obvious signs of infection causing it. I discovered that I could eliminate it by sterilising my toothbrush, but as I used to leave the brush in water with a drop of Oil of Oregano, maybe it was the antihistamine factor rather than the boiling water!!

I had a very mild case of what I believe was Covid last December but after it, my body went into overdrive in various ways which I believe to have been mast cell activation. It took many months to calm it down, and I am not convinced that I have totally managed that. I have eliminated some things from my diet, but there is no doubt that I can no longer tolerate much stress, and unfortunately the last 2 years of my life have been one stress after another! Thankfully things should improve soon on that score at least.

I am taking some of the natural mast cell stabilisers on an ongoing basis, and I am sure that they are helping to keep things on a more even keel for me, except when either my foods, or stress of some sort tip me over.

Hi Elaine

I had the stomach pain with LDN at first, as well. I had completely ruined my stomach and small intestines by trying berberine for SIBO. Ended up in the ER and they did gastroscopy, finding excoriations all the way down. I’ve been worse ever since. Then I tried LDN. It was beginning to work when I went from .25 mg to .50 mg, but the pain was really bad. I confinced my naturopath to prescribe topical LDN and I’ve been on it ever since, now up to 6 mg, very slowly over a year’s time. My fibromyalgia is better, but my gut is still pretty messed up. Maybe you could try the topical?

Thank you Ann.

Unfortunately I did try the topical LDN for about a year. I didn’t have any significant change either way, though I would be prepared to give it another try as it was now some years ago.

Sorry to hear this, Elaine. I hope you find something that works!

Have been unwell for 50 years, 30 years ago mast cells dedected in the bladder. Noticed beeing better on antihistamines.

The lack of knowledge and interest by doctors in this astounds me. I hope they can come up with smthg fast

I wonder if this is why mirtazapine has been one of the best things I’ve taken for my me/cfs as it has strong H1 blocking effects. Even though it knocks me out I am so much more awake during the daytime, especially with the body fatigue. I do wake up every morning congested and blowing tons of mucus the first hour or so but I’ve been told I have a dust mite allergy. I’ve also always had loose stools, I was diagnosed with celiac disease 10 years ago and despite being on a strict gluten free diet I still have a sensitive digestive system and loose stools. The one thing that’s helped me with the loose stools for some reason has been green tea. I asked my autonomic neurologist at Vanderbilt if I could possibly have MCAS and she just said no, so I have no idea. I do hate how dry my skin, mouth and eyes are from taking mirtazapine and worry a little bit about the long term consequences of that.

I’ve heard long term use of Benadryl can cause memory problems and although not as bad as PPI’s, the H2blockers can weaken bones over time. Wonder how prevalent these side effects are and how long it takes with daily use to see issues with these type drugs…..

I think many antidepressants have anti histemic qualities. For some if us it might be the mode of action

Don’t forget, MCAS is not “recognized” by most of the mainstream medical establishment! Since there is no test for it it doesn’t exist. You have to find a Dr who isn’t lazy and cares. Most specialists don’t fit that bill.

Hm, well I have IBS (and Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome), but I don’t tolerate antihistamines at all. In fact, I personally gain from taking Histidine, the histamine precursor. I find it modulates serotonin, which is a big problem in my case. Incidentally, most of the serotonin in the body is found in the gut. I’ve begun to suspect that I have issues with serotonin metabolism, which in turn could be down to problems with the CYP3A4 enzyme (and gene). These types of enzymes reside in the liver and the gut. I think this sort of thing should also be looked into. Just my experience.

My doctor just prescribed Gastrocrom for my IBS. Does anyone have experience with this? (I already take Famotidine and Zyrtec.)

I just started the generic version 2 days ago! 🙂 So far my nose and throat have been more clear than they have been in YEARS. My nose had also been very gross since I overdid it a few months ago, and that FINALLY cleared back up (the rest wasn’t cutting it). I think it’s also reducing some chronic swelling in the back of my throat, since it all feels clear, vs using my nose spray, and only the back of my throat feeling overly dry like each breath is hitting it, and needing to drink tons of water to counter that feeling.

It’s hard to say on the digestive side, since I have also increased my Midodrine & Baclofen. The Midodrine upsets my stomach, and my digestion slows to a crawl until I adjust to new medications or changes in dosage.

it’s also possible that it’s helping my BP a little, since my HR has seemed a bit lower, however it could be a fluke/ placebo, etc, too soon to say! I set a reminder to check my improvements in a month when it should be at full effect. I will try to remember to post back here once everything has stabilized 🙂 … since I also am crashed from traveling for medical care lol … and yes I know I should not have started all of these changes at once.. but it’s hard to wait when I hope every change/ med/ etc will be the silver bullet! haha 🙂 Best of luck to you! 🙂

jo & Sara

I take quercetin because it’s over-the-counter and it may avoid the side effects of Benadryl. It’s been called the plant benadryl and I can tell you that it has cleared up my nose and throat that have been drippy for all of my adult life. I was one of those persons you don’t want to be in the same room with – constantly clearing their throat and sniffing. Worse in winter. I based my decision on this study:

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3314669/

the title of which is: “Quercetin Is More Effective than Cromolyn in Blocking Human Mast Cell Cytokine Release and Inhibits Contact Dermatitis and Photosensitivity in Humans”

Cromolyn is the generic version of Gastrocrom. Quercetin made a huge difference for me.

sorry, should have mentioned, already on Zyrtec 2x daily, Ketotifen, singulair, for the MCAS like symptoms – the singulair & ketotifen have clearly reduced the flushing to only my face, and calmed some of my IBS symptoms, while the Zyrtec helped reduce some of the blotchy, dark vision, so that was a lead for my dr to continue on this route. My digestive health expert helped me notice that it’s probably an autonomic issue with my digestion stopping/ slowing with any medication changes.

Thanks to Lono for sharing his experiences with mast cell treatments as a “mask” of some symptoms, which in some cases may carry risks of lulling one towards over-exertion. Like Lono, I’m working full-time, but am continuously questioning whether it’s a good idea.

This reminded me to share out this paper about how anti-histamines are “effective” in long-Covid:

https://www.news-medical.net/news/20210608/Antihistamines-might-be-effective-in-long-COVID.aspx

When you actually look at the paper, what you see is it improved many symptoms EXCEPT the two core symptoms: PEM and dysautonomia (incl. orthostatic intolerance).

Fwiw, this is consistent with my limited experience to date with a mast cell treatment (with Lactobacillus rhamnosus, a mast-cell downregulating probiotic). It nearly abolishes my dyspnea and voice/throat complaints, but doesn’t seem to touch my PEM or orthostatic intolerance.

That’s why I’ve been recently hypothesizing that histamine symptoms may be due to the microbiome shifts induced by ME/CFS, i.e. a downstream effect. But now this work raises for me another possibility that mast cell dysregulation can arise in tandem with T-cell dysfunction, from the same B-cell “bad memory”. And when it does, the mast-cell stuff may be annoying while the T-cell dysfunction is more truly debilitating.

Thanks to Vivien also for sharing her experience. This reminds me of my female friend suffering from long-Covid who also spoke of her anti-histamine intolerance. It’s just an N of 2, but even so this reminds me of Dr. Nath’s recent teaser of the NIH study results: turns out men and women are different! At least immunologically 🙂

Viyer05,

Continuing to work is a tricky one. I’d be classified as a moderate case of ME/CFS, but I was mild for years until I couldn’t work any more, I guess. Certainly the advice for establishing the best chance of recovery at the onset of ME/CFS is to just rest. But that is not always possible. People’s lives just don’t allow for it sometimes.

In the end, the “brain fog” over took me such that I couldn’t even be functional in a job I’d been doing for 20 years. Including weird things like forgetting the phone number you’ve had for decades for hours at a time, then it just “reappears”. And I was a fatigue risk around heavy machinery.

You mention the throat/speech problems. That was the first symptom that was recognised and triggered my diagnosis. The dietician I mentioned above worked at the clinic run by the immunologist. She heard my speech problems and then shuffled me through the side entrance to see the immunologist (otherwise booked out for 6 months or longer). If it wasn’t for her being sharp enough to pick up on that, things would have been very different.

Whilst not wishing these symptoms an anyone, isn’t it great to see a long-Covid paper referring explicitly to PEM. For me at least, the fact that H1 and H2 antagonists didn’t change PEM is another bit of evidence that long-Covid and ME/CFS have a lot in common (albeit, non gold standard).

Good luck with hanging in there.

Interesting the mast cell component. I was diagnosed with Sibo finally after a misdiagnosis of IBS. Interestingly I also have Interstitial cystitis. If I am not managing my Sibo well it activates and triggers my IC. I have always thought that there might be a mast cell component in this.

Can you post which new mast cell stabilizers are under development?

The link won’t be readable on my phone, it’s asking for payment subscription.

I actually don’t know which ones but plan to look it up.

The best description and guide to mast cell activation syndrome I have seen is here:

https://www.legalnomads.com/mast-cells/#Mast_cells_and_Pain_in_Fibromyalgia_a_2019_Study

There are multiple resources here and it is a long page, but very much worth it.

Thank you so much for sharing my page. I try to update it as new things come out (I’ve got a few more studies to add soon). If you have any additional things that you think are missing, feel free to email me via the site’s contact page. Glad it was helpful.

Such interesting and complex topics in article and comments!

My basic belief is that our natural body systems need to have all the energy we can give them, because they can deal with extremely complex issues pretty well, given the chance.

This means that rest is the most effective element of treatment of all.

Obviously it can be helped by various targeted drugs, I’m not knocking all the research and advice found here, at all.

But rest has such a stigma, and we energetic, positive people hate and resist the idea.

When reframed as ‘the best treatment yet available’, maybe we can shift our feelings about it.

When the process is given a different label: minimising muscular exertion, and we do a systematic analysis of where in our lives we can economise exertion (in order to keep doing the things that are important to us), it becomes a matter of logistics.

For example, holding up our heads involves constant muscular movements balancing an object weighing about 10 lb. We don’t think about it, but if we had to hold a bowling ball in our hands all day, we would!

When in a high level advisory post in the social services, I learned that if I kept my head supported, even if it meant moving my chair in order to lean against the wall, I could keep track of what was going on in meetings, and make a sensible contribution.

In the course of daily life, when my cognition fails, all I have to do is lie down for half an hour for it to return.

If we can harden ourselves to forget embarrassment, seeming selfish or like a hypochondriac, and go through our days expending exertion only on necessities/things we enjoy, and refuse to lift anything heavy, struggle with opening a jar, stand to speak with people when we need to politely excuse ourselves in order to sit down, regard labour-saving devices as a form of medical treatment worth the expense, you think of your own examples…this energy conservation can enable us possibly to keep our jobs, or some social life, the things that we need to retain our income/sense of our identity.

This, I feel, should be a fundamental principle of our lives as we continue to pursue all the medical help we can get, and to support all the research we can afford to.

It has been show that there is a functional deficit of B12 in both CFS and MCAS

https://b12oils.com/mcas.htm