It didn’t take David Systrom long to take on long COVID. Systrom – the Harvard pulmonologist whose invasive exercise tests are redefining how we think about chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS) – didn’t lead this study but helped design, analyze it, and write the paper. The study was led by Yale pulmonologist Inderjit Singh. Like Systrom, Singh is one of the few pulmonologists who has his hands on an invasive exercise machine.

“We are one of the few centers in the world that performs invasive cardiopulmonary exercise test (iCPET). We primarily perform iCPET for patients who have unexplained shortness of breath or fatigue. So, these are patients who’ve had all the routine investigative testing, all of which do not explain their symptoms.”

Singh appears to be coming to long COVID (and ME/CFS) in the same way that Systrom did: by coming across people with mysterious fatigue and/or shortness of breath. Instead of directing them to the nearest psychologist – as most pulmonologists apparently do – Singh appears to have taken them on.

It’s hard to overstate how important the long-COVID exercise studies are both to people with long COVID and/or ME/CFS. Exercise, after all, is, in one form or another, recommended for most diseases and conditions. Until ME/CFS came along, few people had considered the possibility that exercise could be a) fundamentally harmful; b) or instead of making you stronger, it could make you, in a very fundamental way weaker; i.e. it could actually impair your ability to make energy.

These studies present the opportunity not just to better understand these diseases but to rethink fundamental assumptions that have been made about human biology – assumptions that have undermined the efforts to understand ME/CFS and other diseases. A recent study, for instance, exploring exercise intolerance in rheumatoid arthritis, found some intriguing similarities to ME/CFS.

Persistent Exertional Intolerance

The title of the newest study, “Persistent Exertional Intolerance After COVID-19 Insights From Invasive Cardiopulmonary Exercise Testing“, adds a nice qualifier: the exertion intolerance isn’t temporary – it’s persistent, and exercise isn’t the issue – it’s exertion – a much, broader, more inclusive and descriptive term that hearkens back to a proposed name for ME/CFS (Systemic Exertion Intolerance Disease (SEID)).

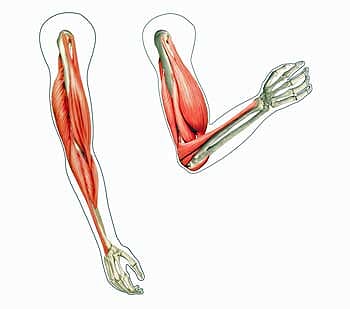

The straight lines present the predicted levels of oxygen utilization. Note how much lower the long-COVID patients were.

The study was small (just 10 people) but it contained long-term (for long COVID that is) patients – all had come down with long COVID about a year before. The one person to see the inside of a hospital room was hospitalized for a short time.

One of the graces of the invasive cardiopulmonary exercise test (iCPET) is that, unlike non-invasive CPETs, it takes just one invasive test to uncover some rather dramatic problems with energy production in ME/CFS.

The results were familiar. The limited ability to exert oneself was not a cardiac issue but was found somewhere in the periphery; e.g., something was happening in the blood vessels and/or the muscles.

- The “Markedly reduced aerobic capacity” (peak VO2 <80% of expected) – indicated that the long COVID patients were unable to produce normal amounts of energy. (Aerobic capacity involves the use of oxygen via the Krebs cycle to generate energy. It’s the main source of energy for the body.)

- High blood oxygen levels at the moment of peak exertion – indicated that the lungs were delivering sufficient amounts of oxygen to the blood but the oxygen was not getting taken up in normal amounts by the muscles.

- Increased oxygen saturation found in the venous blood – cinched the former finding. Since the veins direct the blood back to the heart after it has gone through the muscles, the blood oxygen levels of the venous blood should be much reduced. The higher levels of blood oxygen found in the veins of the long-COVID patients indicated their muscles were not taking normal amounts of it up. Because the mitochondria use oxygen to produce ATP they weren’t able to produce as much energy.

- Hyperventilation – Carbon dioxide (CO2) is a byproduct of energy production which is removed via breathing. CO2 is toxic in high quantities but healthful at the proper levels. Rapid and deep breathing (hyperventilation) removes too much CO2, and results in narrowed blood vessels and symptoms like fatigue, cognitive issues, etc.

- Significantly reduced left-side filling pressure – Systrom’s ME/CFS studies indicate that not only are the blood oxygen levels increased in the venous blood but that leaky blood vessels are causing some of the venous blood to disappear – resulting, if I have this right, in reduced left-side or diastolic filling pressure.

It was truly all of a piece. The reduced aerobic capacity made sense given the finding that the raw material of energy production – oxygen – was not being used up. Either the oxygen was not getting through to the muscles in normal amounts or, if it was getting there, the mitochondria were not taking it up.

Deconditioning Rears Its Head

“By using iCPET, we provided a comprehensive and unparalleled insight into the long term sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection that is otherwise not apparent on conventional investigative testing”. The authors

Multiple studies have shown that while deconditioning is present in ME/CFS – it is not causing the energy production problems in the disease.

Exercise studies can be dangerous things. Exercise tests that delve more deeply into exercise physiology will reliably pick up abnormalities in ME/CFS patients. Exercise studies that skirt the surface may not.

It’s no surprise that the idea that deconditioning (lack of activity) is causing exercise problems has shown up in long COVID. The deconditioning idea led large parts of the ME/CFS field astray for decades.

Thus far two long-COVID studies have concluded deconditioning is causing the impaired energy production found. One study which found a keystone ME/CFS result – early entry into anaerobic functioning – concluded that absent problems with the lungs, deconditioning must be the cause. Another study that found reduced peak oxygen consumption – another common finding in ME/CFS – also concluded that absent any evidence of problems moving oxygen into the blood, deconditioning must be the cause as well.

Inderjit et. al also asserted that the authors’ assumptions were faulty because two hallmarks of deconditioning (reduced peak CO, increased heart-filling pressures) were missing, and one of them (heart-filling pressures) actually moved in the opposite direction expected.

More complete exercise tests – the 2-day exercise tests and the invasive exercise tests – as well as other studies have incontrovertibly shown that while deconditioning is, of course, present, it is not responsible for the energy production problems in ME/CFS.

Enter Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS)

The authors then went on to propose that a similar process to that found in ME/CFS may be occurring in long COVID. A small fiber neuropathy that’s shunting the blood away from the muscles (and presumably other tissues) is preventing oxygen from getting to the mitochondria.

Systrom’s team has come up with other possibilities including mitochondrial problems, “leaky veins” which reduce blood flows, and low blood volume, but the small fiber neuropathy/microcirculatory shunt appears to be the best fit for this small group of long-COVID patients.

A Heart Failure Connection?

The authors highlighted the “exaggerated hyperventilation” found during exercise. (Hyperventilation occurs when you breathe more quickly and deeply than normal.) They concluded that the abnormally high “ventilatory efficiency” was likely due to an enhanced peripheral mechanoergoreflex and metaboergoreflex sensitivity.

Twelve years ago, Alan Light appears to have found something similar when he found dramatically increased levels of metabolites produced by the muscles.

Something akin to heart failure may be affecting the skeletal muscles of people with long COVID and/or ME/CFS.

The authors then dropped a bombshell when they suggested that the skeletal muscles in people with long COVID may be undergoing a process akin to that seen in heart failure (!). They suggested that along with alterations in the makeup of the long-COVID patients’ muscle fiber types, the enzymes responsible for activating aerobic activity may also be depleted.

That depletion would block the ability to produce energy aerobically, thus causing an early dependence on the less productive and ultimately toxic (when overused) anaerobic energy pathways. That would then cause the small (group III-IV) nerves associated with the muscles to send out signals calling for more rapid, faster breathing; i.e. hyperventilation. Since Systrom has also found hyperventilation during exercise in ME/CFS, the same should apply to ME/CFS as well.

The Gist

- This small study – led by a Yale pulmonologist- and involving David Systrom, did the first invasive exercise testing of people with long-COVID.

- The study’s results – reduced energy production, reduced uptake of oxygen, and hyperventilation, jived with Systrom’s findings in ME/CFS.

- Two long-COVID exercise studies have concluded that deconditioning is causing the energy production problems in long-COVID. This more comprehensive invasive exercise study showed that it wasn’t.

- The authors proposed that something similar to what’s happening in ME/CFS may be happening in long-COVID as well. A small fiber neuropathy that is shunting the blood away from the muscles (and presumably other tissues) is preventing oxygen from getting to the mitochondria in the muscles – thus reducing long-COVID patients’ ability to produce energy.

- Attempting to explain the hyperventilation, the authors hypothesized that something akin to what occurs in heart failure may be occurring in the skeletal muscles in long-COVID patients. Studies indicate that the exercise intolerance found in heart failure is partly due to alterations in muscle fiber types and reductions in aerobic enzyme production. Those changes appear to trigger the nerves in the muscles to produce hyperventilation during exercise.

- This DOES NOT suggest that heart failure is a possibility in long COVID. (Decades of ME/CFS have not produced heart failure in ME/CFS.) The heart failure hypothesis appears to apply to the skeletal muscles – not the heart – which is not a skeletal muscle.

- It’s clear that as time goes on exercise physiologists are delving deeper and deeper into the core issues found in ME/CFS and now long COVID.

- Since the pioneering work of Workwell and Dane Cook in the 2000s, the exercise physiology field in ME/CFS has steadily grown in significance and breadth. Long COVID is bringing more exercise physiologists to the ME/CFS field and more are sure to come – taking us hopefully closer and closer to the heart of what’s happening in both diseases.

The skeletal muscle finding, interestingly, came about when researchers tried to understand why people with heart failure experienced such dramatic exercise intolerance. It turned out that the exercise intolerance was in part due to reduced aerobic energy production and an early entry into anaerobic energy production – precisely what is happening in ME/CFS. Establishing a link between long-COVID and ME/CFS, and a disease like heart failure would, of course, be a huge step forward for both diseases.

It should be noted that Ron Tompkins of the Open Medicine Foundation-funded Harvard Collaborative Center for ME/CFS is studying the muscles in ME/CFS.

Conclusions

The study was small, but David Systrom has assessed hundreds of people with mysterious fatigue and exercise intolerance over time and knows his subjects well. I would be shocked if this small sample wasn’t representative. Despite the small sample size, the authors noted how striking their findings were.

“Data for this study were drawn from a small number of patients who had recovered from COVID-19. However, the peripheral limitation to exercise intolerance exhibited by the patients who recovered from COVID-19 were striking compared with those of control participants.”

All study to date suggests that energy production problems in long COVID match up well with those in ME/CFS.

Slow Moving Revolution

It doesn’t appear that anyone seriously considered the possibility that exercise was damaging the ability to exercise, or even more importantly, was able to document it until the exercise physiologists at Workwell group (Staci Stevens, Christopher Snell, and Mark Van Ness) began doing 2-day exercise tests in ME/CFS over ten years ago. When I first came across Workwell’s work in 2009, I assumed it would revolutionize our understanding of ME/CFS – and it has over time – but much more slowly than I would have thought.

For one thing, those 2-day test results so messed with exercise physiologists’ heads that rather than believing them, they assumed something MUST be wrong with Workwell’s testing equipment.

Inderjit Singh teamed up with David Systrom and brought his invasive CPET machine to work on long COVID. (Image from Yale University).

Exercise studies are now routinely used to provide insights into ME/CFS pathophysiology, and multiple studies have confirmed Workwell’s early findings. Since Workwell and Dane Cook at the University of Wisconsin began digging into exercise and ME/CFS in the 2000s, other exercise physiologists such as Betsy Keller, Ruud Vermeulen, Franz Visser, and David Systrom have joined the field. Their work inspired Avindra Nath to include an exercise study in his NIH intramural study.

The pre-COVID-19 ME/CFS exercise physiologists prepared the way for long-COVID exercise physiologists who are being greeted with some startling findings. Donna Mancini is studying both long COVID and ME/CFS (she and Dr. Natelson recently snagged a huge NIH study), and Inderjit Singh noted the ME/CFS results in his long COVID study.

These two will hopefully be just the tip of the iceberg as more exercise physiologists and energy production specialists join the field and take us closer to the heart of what’s happening in ME/CFS.

I remember doing a stress test in my early 40’s after complaining about not being able to breathe and the pulmonologist failing to turn up any lung problems. I not only hyperventilated during the test, I sat down next to the treadmill afterwards, heaving heavily for quite some time. The staff wasn’t at all concerned, kind, nor did they note my condition or even bother to wait until my obvious distress dissipated before they left me alone in the test room, casually bantering about their lives. It was so humiliating, considering I used to be an athlete.

It’s hard to believe that they don’t seem to have treatments to help us get the blood flowing. Will this lack of blood to the tissues likely cause permanent damage to the tissues or the nerve endings? When they do find a treatment, will we reanimate after decades of disease? Wouldn’t that be awesome.

, Barbera. Something similar happened to me during/after pulmonary function tests at Mayoclinic…..no lung problems, but I had to lay down on waiting room floor for over an hour…I thought I was dying!

Barbara, the same thing happened to me. The person in charge very dismissively said that I was just very unfit. How could I exercise during 5 years of barely being able to walk? The staff has the same uninterested attitude whilst I was sitting and shaking like a jelly blob, labouring for breath.

It’s baffling that human beings can be so insensitive and uncaring. Sorry you experienced that Barbara.

The only explanation I’ve come up with is they need, psychologically, to believe these experiences are your own fault. They need to blame the patient because if it’s not your own doing, it could happen to them.

Reality is, it could happen to them, because this has happened to people from every background and lifestyle. But they do not want to believe that so they blame you for your ill health.

Those professionals should be ashamed. They had no compassion or even curiosity at all and never doubted themselves in the face of patient after patient stories if they cared to listen.

I’ve had these issues beginning at 32. I’ve had many good and great decades since, where I’ve had lots of energy and the ability to exercise as I please. I’m 67 now, so I’m my opinion and experience, yes, I was able to heal fully from CFS, ME, fibromyalgia, at lengthy periods of time. Mine was caused from a post viral syndrome from Epstein Barr Virus. All the best to you!

Hello, how do you heal? I am long covid and I would like to know more about how you did to recover if you had any special treatment, sports, food? To have another idea, your message gives me hope that this will end one day and I can go back to being the one I used to be with energy and life, thanks

Hi Barbara,

I tried lots of things for my CFS. Then someone on a thread suggested creatine. When I added it to the mix my energy started to return. I’d thought I was going to be stuck in that awful fatigue forever. It was amazing but it might have just been a coincidence idk. Maybe worth a try. Good luck

Creatine is definitely worth a try. A blog on that is coming up. Congrats and thanks for spreading the news. 🙂

The same happened to me, except the Cardiologist told me that there is definitely something wrong but I needed to look elsewhere because it is not my heart or lungs.

“When they do find a treatment, will we reanimate after decades of disease? Wouldn’t that be awesome.”

As a former athlete myself – yes, it surely would be.

Wish I could understand this better, especially since I got a heart failure diagnosis (along with the mecfs) about 5 years ago (diastolic dysfunction).

It’s not easy….The gist for me is that long COVID continues to look very much like ME/CFS, that experienced researchers are using really strong tools (invasiveCPET’s) to hack away at both long COVID and ME/CFS, that they’re finding strong deficits in energy production and that hopefully, studies like this will spark a wave of research that will finally get at what the heck is going on.

I wondered after Cort’s article (early May?), “Damaged Small Nerve Fibers May Be Causing Energy Problems in…ME/CFS,” whether my decades-long ME/CFS and SFN are impeding the recovery of my right arm after a total shoulder replacement 18 months ago. That was 5 months after I broke the upper part of the humerus and an original surgery failed, owing to avascular necrosis. Range of motion is now quite good, but restoring the muscles is much harder than my surgeon anticipated, despite daily exercises and twice-a-week P.T. with a skilled and understanding therapist. That progress is “glacial” (the latter’s term). This study seems to indicate where the trouble lies. Has anyone experiences from which my team and I can learn?

Interesting that it’s the muscles that are having difficulty recovering. I’ve always thought something must be going on in the muscles. It’ll be interesting to see what Ron Tompkins finds.

When can we expect the results from tompkinns muscle study?

Even though it seems counter-intuitive, perhaps more recovery time between sessions is needed.

Yes, you and the therapists, most likely should be doing a lot less.

You work a muscle before they get to the point of being tired

This point will come a lot sooner than you and your therapists think.

I tend to feel it in my brain/mind before I feel the muscle tiring.

a feeling that I want to stop what I am doing

I can’t stand doing it anymore or my brains will explode

(something that might look like ADHD in the outside)

You don’t do a different exercise with the same muscle.

You let it rest and move on to a different one.

Your body will let you know when the baseline increases and you can do more.

Eating a minimum of protein and carbs, etc.

Infra-red light may be good to try.

Again, you start with a lot less of the time exposed that is recommended

just like most of us need to take very small micro-doses of sups and hormones

etc

Doctors and health professionals seldom have any clue what our baseline is

They keep pushing thinking it is good.

It’s the same concept as with (an)aerobic exercise in ME/CFS:

Pacing. And often your baseline is a lot lower than you realize.

I have only met one – a hydrotherapists that works with all kinds of diseases and a lot of experience with children with all kinds of problems that don’t even have names yet. Let’s the patient guide treatment, as opposed to imposing it.

I learned this when I was doing biofeedback for pelvic floor therapy.

Because of hypertonus, the exercise was to relax the muscle.

After just a few reps, the resting tone of the muscle would go UP.

Meaning that the muscle would tense up even more at rest than when I first started the session.

I would stop, and the next day, my starting resting tone was still higher – it had not gone down to baseline.

I am baffled how the therapist could think this was working.

The objective of therapy was to *reduce* the resting tone…

My nerves were injured, after just a handful a sessions.

Same with the EDS specialized therapist. They really have no clue.

Maybe you can use a biofeedback device at first,

sometimes it is hard to reach certain muscles with it.

I find that as I work on improving my metabolism,

the resting tone also improves and muscles don’t get as tired as easily, etc.

I still have ways to go.

Meirav, I think my red light set up helps me a lot. People keep going to doctors’ offices and physiotherapists to have red laser therapy or red light therapy and I think we know why. Laser therapy helps broken bones heal faster. We also know that it’s not the laser, it’s the wavelength. If you get LED’s strong enough at the right wavelength, it enhances mitochondrial functioning.

If you go here:

https://theenergyblueprint.com/red-light-therapy-ultimate-guide/

and scroll down (or search for) Chronic Fatigue Syndrome and Fibromyalgia, you’ll see how that happens, plus references up to 2017.

I have a unit that I use every day. It seems to be helpful

More studies:

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2996814/

A summary of recent research by New Scientist:

https://www.newscientist.com/article/dn27877-burst-of-light-speeds-up-healing-by-turbocharging-our-cells/

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1011134420305388

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2214647416300381

https://www.science.gov/topicpages/l/low-level+light+therapy.html#

Yes on infra-red light!

So on sunlight (UV-filtered, through a window that has a coating or early in the morning).

Well over a decade ago, I remember Dr Myhill already saying on her website: “CFS is low cardiac output secondary to mitochondrial malfunction” – https://www.drmyhill.co.uk/wiki/CFS_-_The_Central_Cause:_Mitochondrial_Failure#CFS_is_low_cardiac_output_secondary_to_mitochondrial_malfunction

… But she seems to say it’s the mitochondria of heart muscle cells with low energy output causing the heart’s output to drop and reduce circulation to the rest of the body.

Whereas the studies in this article are siting only peripheral causes reducing use of plentiful blood oxygen; so no notable issue with heart muscle cells?

I think you had an important typo: “…the blood oxygen levels reduced in the venous blood…” should be *increased* as you described directly above, right?

Yes, they haven’t found any evidence that impaired heart function is behind this. My understanding is that if stroke output is impaired it’s probably because the heart isn’t getting enough blood. It’s the stuff happening out in the blood vessels and muscles that is the problem.

Right – it should have been increased – definitely increased!

Thanks 🙂

“it takes just one non-invasive test to uncover some rather dramatic problems with energy production in ME/CFS.“ should this read, “it takes just one invasive test”?

OMG – yes. One Invasive test…..Thanks. You guys are good readers!

Hi Cort , how can I follow you and your up to date info in CFS ?? 😇

Subscribe to the newsletter! If you look to the right on the page you’ll see a subscription widget :). Thanks for asking.

Has anyone tested how long it takes to recover to the 1st day energy levels after the day 2 drop?

From Workwell Foundation’s website, scroll all the way down to the last FAQ at the bottom:

https://workwellfoundation.org/testing-for-disability/

“Approximately 50% of patients recover to baseline within 4 days. Some take up to a week, and in rare cases longer than a month.”

How is too low CO2 “causing symptoms like fatigue, cognitive issues”? Is it via increased blood pH, as CO2 is acidic?

Also, what do you make of Dr Asad Khan seeing *low* venal O2 saturation in his venous blood gas test?: https://twitter.com/doctorasadkhan/status/1452065627124998154/photo/1

Alt text on his image says: “Peripheral venous blood gas taken from antecubital vein showing low oxygen saturations. Indicative of excessive oxygen extraction by energy starved tissues. Reference ranges vary but UpToDate quotes 65-75%. Mine was 32%.[…]”

Could it be that things reverse at rest? Oxygen consumption is higher than normal, from slower moving blood? If he’s right about disordered (micro)coagulation. Or would this be an opposed result, maybe indicating a different sub-group of Long Covid, or something else?

ZeroGravitas, I caught one of Dr. Khan’s videos and he noted there were two countervailing effects: one of reduced 02 extraction and another of oxygen-starved tissues seeking to consume more. So if I’m gathering correctly, out-of-range venous oxygen, whether low or high, could at least be supportive of an ME diagnosis.

I am experiencing periodic hypoxia (perhaps technically hypoxaemia) during sleep. What I think is happening is that I have hypocapnia (low CO2), which reduces the volume of my breathing (I can see this in data from my CPAP machine) in order to allow CO2 to increase, which then results in hypoxia because I am not breathing enough oxygen in. In sleep, the hypoxia causes an arousal, which restores more normal breathing but also causes all of the fatigue, brain fog, head aches, muscle aches etc. that I wake with.

Does the same mechanism work when awake? I don’t know. But I did once have an SpO2 monitor on my finger when I put a face mask on and, counterintuitively, I saw my oxygen saturation go up.

Low c02 means you cannot offload oxygen into the muscles. It’s called the Bohr Effect. You need co2 to generate oxygenation of tissue. Oxygen in the blood is not the same as oxygen in tissue

Ah, thank you both! From Wikipedia on Bohr Effect: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bohr_effect

“Hemoglobin’s oxygen binding affinity […] is inversely related both to acidity and to the concentration of carbon dioxide.”

So, CO2 production in tissues increases (localised) acidity of the blood, through bicarbonate production that lowers the pH, thus liberating oxygen from blood cells more rapidly, there.

So if our cells are producing less CO2, from less aerobic respiration in mitochondria, the delivery of oxygen will be less efficient, normally.

However, the wiki article also states that *lactic acid*, from (intense) anaerobic energy production, lowers pH even more rapidly than CO2 would! So under exertion, oxygen removal from our blood could be more intense than expected…? Hence a potential presentation of opposite extremes…?

What a profoundly uplifting article. I feel we are on the cusp of a breakthrough. I’ve had this for almost 2 decades and I have never felt more hopeful. I realize this is a tasteless joke, but perhaps a viagra-like medicine targeted to “other” muscles?

I’m feeling pretty excited as well. I love how these guys are steadily getting deeper and deeper into this. I’m hoping that the NIH and others latch onto this and a wave of resources and money gets devoted to these kinds of explorations. It’s nice that these findings fit into other hypotheses like Wirth and Scheibenbogen’s and findings regarding cellular energy production really nicely.

Cort, thank you for another fabulous article. There is soo much here. Thank you for all the links included, too.

imo, this article is an extremely good one to pass on to friends, family, acquaintances, neighbours, nurses, doctors….

The small fiber neuropathy is important to include in studies. So i would like to see Alain Moreau, etc. and those mentioned here testing for it and including it as part of their research.

found a link describing one person’s experience of the iCPET

https://www.mentalolympian.com/a-new-chronic-fatigue-syndrome-treatment-available-after-diagnostic-icpet/

Could it be a venous insufficiency problem? Looking forward to the future and what is discovered.

https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/health/conditions-and-diseases/chronic-venous-insufficiency

What role might Mestinon play in this mechanism? I think I first heard of this medicine from one of Dr. Systrom’s talks.

I suspected Mestinon might help because acetylcholine is an important signaling molecule for the muscarinic M1-M5 receptors. Autoantibodies, such as those found by Dr. Carmen Scheibenbogen, might block that signaling. Mestinon could then help restore the signaling by inhibiting the breakdown of acetylcholine so that more is available for signaling.

But perhaps there are better explanations for how Mestinon might work.

I was thinking mestinon when someone mentioned a viagra-like treatment targeting the muscles. I’ve been taking 90 mg a day for a few months now, and it’s been fascinating. Muscles generally seem more toned and eager for exercise. But I won’t really find out if it increases my exercise tolerance until I recover from upcoming hip replacement. If you can talk your cardiologist (or whoever) into letting you try mestinon, I found getting the dosage right is crucial. Once I got that nailed down my body sort of craves it in the morning, because it feels a lot like a stimulant at the muscular level instead of in the brain. Whether it’s a breakthrough or a tweak, I expect to keep benefiting from it.

I took Systrom’s iCPET. The results indicate Preload Failure of the RIGHT Heart, not left. Right atrium to be specific.

Cort, aren´t you surprised that their explanation of muscular failure does not include autoimmune changes to vasoregulatory G protein coupled receptors (AT1, beta 2 etc…)? I mean it ´s physiologically plausible that dysregulated vascular blood flow contributes to muscular failure, and these autoantibodies have been found in virtually all Long Covid patients (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33880442/). Instead they discuss small fiber neuropathy (which of course may also be present but remains to be established). I am just wondering because to me it doesn´t seem to be a straight line they are drawing there.

You’re correct, GPCR auto antibodies to the autonomic nervous system could quite easily cause a physiological shunt that results in reduced blood flow to exercising muscles. The brain would be similarly affected as it normally receives 15-20% of the cardiac output though accounts for only 2% of the total body mass. Hence brain fog.

Also fatty acid and carbohydrate metabolism is dependent upon the sympathetic nervous system, so abnormal metabolism could also be present.

Nothing changed yet. Most doctors still think that the cause is deconditioning . The disability insurance companies are very happy with that. Long Covid patients are treated just as badly as ME/CFS patients. Which is still happening. After 30 years, nothing has changed at all.

Cort, my English is not perfect sorry, but Franz must be Frans 🙂

Thx for your new blog!

I think they should start measuring blood volume in patients with abnormal values.

Actually a post mortem study of cause of deaths in MECFS patients found a statistically significant reduction in age of mortaility from heart fatilure with MECFS patients averaging 25 yrs younger death from heart failure. The only other statistically significant change in mortaility was overall and from suicide.

That’s a study – https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5218818/ – that much approached with extreme caution The study didn’t find increased heart failure it found an increased rate of “heart disease” which includes many conditions as well as other cardiovascular diseases (stroke, etc.) as well as cancer.

Because the small study took as its subjects people from a website which simply listed deaths many possible confounding factors exist. We don;t know if it was a representative sample (it clearly focused on more severely ill patients). we’re relying on others to state the people had ME/CFS or to know what they died of. In fact, the paper states “Thus, it is not possible to generalize these findings to the overall patient population.”

A much larger, more rigorous study (which I’m sure had its own problems) did not find an early increase in mortality from cardiovascular or other diseases but did find an increased risk of suicide. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26873808/

Another study of Jason 2006.

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/6940506_Causes_of_Death_Among_Patients_With_Chronic_Fatigue_Syndrome

The larger study you mention was from Wessely and Chalder. They use mostly Oxford criteria only fatique. So this study isn’t representative at all.

I think ME/CFS/POTS can definitely lower life expectancy. No doubt.

And as you get older and have CFS for longer, the risk of lymphoma increases (NHL).

https://acsjournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/cncr.27612

I also have my reservation that the heart doesn’t suffer in ME/CFS.

Too long to go into here, and still in the midst of reading/researching.

A quick example is that hypoxia can lead to fibrosis and calcification of tissues, including the heart and aorta. There are other angles to heart issues in ME/CFS, stemming from the HPA axis dysfunction.

Demo…

I checked the study you are citing and I see that it was written by no other than

S. Wessely…

That’s one of the individuals in the UK responsible for shaping the view of ME/CFS = Neurasthenia = MUS = mental?personality weakness, therefore –> CBT

That is, one of the origins that lead to the fiasco of NICE guidelines, the failure to recognize it in the UK.. and those countries that look to the UK as their guiding standard, etc.

That approach to Me/CFS is called the Wessely School in his honor…

Read more about it here:

https://davidfmarks.com/2021/03/11/me-cfs-and-the-wessely-school/

The paper and findings cited probably needs a good thorough read…

I tend to agree. I think stem cells, crispr and regenerative medicine in general( telomere relengthening etc) will be the way out of this

I am wondering if anyone has had elevated levels of hemoglobin and hematocrit and/or ferritin. These can be indicators of too much iron, a genetic problem that is treated with periodic blood donations. Oddly, the symptoms are almost identical to ME/CFS.

Re. cardiac involvement. I have found that Dr. Nancy Klimas’ recommendation to wear support panty hose or knee high socks is very helpful, although a challenge in Florida’s heat. Also monitoring your heart rate on something like a Fitbit is very useful. When your heart rate goes too high; stop and rest until it returns to normal resting.

I live at altitude, 9500’, elevated hematocrit is a consistent factor. I do feel better at lower altitude, such as when I snowbird in winter.

I remember when my me/cfs hit me out of the blue. I was playing baseball in college and lifting weights and swimming laps as well for training. Not only did I become so fatigued that I couldn’t stay awake in the dugout during games but my muscles started burning out with exhaustion very quickly, I had no physical endurance anymore, went from easily swimming 20 labs to my muscles burning from exhaustion after one. My strength during weight lifting decreased significantly and my balance and athletic coordination were shot too. Of course back then they gave me psych meds which the SSRI’s did significantly give me more physical endurance but made my brain fog worse and were very sedating with tons of other side effects. Also that is when every time I had lab work I had high cpk levels which doctors would just brush off. I still had to quit baseball and really scale back my exercise training even with meds, it was still very hard to motivate myself to do anything physical.

This makes so much sense to me. I have had ME/CFS for 4 years now, but was recently diagnosed. When I exert myself, especially when I shower, I have to sit down on shower chair afterwords and do breathing exercises to get excess CO2 out of my lungs. You can find exercises like pursed breathing on COPD websites. My left lung is definitely worse than my right. X-rays show lungs are clear and cardio tests show heart is fine. But I can feel my left lung is not working as efficiently as the right. I wondered if I had scarring from the Dec. 2017 flu than bronchitis that caused my ME/CFS. Sometimes I feel like pins and needles are in my veins, traveling thru my arms and legs. I am very in tune with my body, and the pins and needles feeling in my veins is very uncomfortable. I can’t find a Dr. here in SE TN educated on ME/CFS, and my diagnoses came from a Professor at a top university in the east that studies rare diseases.

Thankyou so much for the continued research studies in ME/CFS and Long Covid.

What we should do as ME/CFS patients is ORGANIZE.

We should first find a complaint that ensures we get referred by our primary physicians for “exercise”/stress testing.

Then, we should work together to develop a systematic protocol and safe guidelines – as systematic and safe as possible given the variability of cases – to exercise or exert ourselves the DAY BEFORE the standard exercise test, so that essentially the test is measuring us on the second day. This might not mean pushing ourselves to “crashing.” It might just mean doing activities to our limit the day before, so the next day we are sub-par and would see the PEM effects. Again, we would have to organize and compare notes so we could find out just how much Day 1 exertion would be required to push us into the PEM zone on Day 2.

We could then pool our results into a database – INCLUDING the doctors’ names – so when the results all come back extremely out of range – as of course it’s inevitable that they will – we can demand explanations, demand answers, and even go to the media if necessary with these doctors’ names and ask why they are being so negligent in explaining and treating our condition.

Why are they dismissing so many people with these extremely abnormal findings? Why are they insisting it’s “psychological” when so many people are having the same results? How is it possible to “psychologically” to alter a VO2 max and other physiological parameters of a cardiac stress test? Why isn’t the NIH/CDC taking this more seriously and investigating it? Why are they ignoring this cohort when the abnormalities could very likely shed light on Long COVID? (<– key. That should get their attention). Why isn't Congress approving more funding for all of this? Etc.

It could be a long shot, but if we could organize together to implement a plan like this, with we as a patient group taking it upon ourselves to exercise the day before so we get the second-day ACTUAL ME/CFS results, I think we could really make some important headway. Especially if we tie it to Long COVID and demonstrate how their negligence in dealing with ME/CFS is impeding their efforts into solving Long COVID. Maybe we can even get Long COVID patients on board and REALLY show the commonalities.

How does this relate to what Corlanor does to treat me/cfs? I have been on Corlanor or several months now (thanks to reading the article on here about it!), and have markedly improved. My understanding is that Corlanor slows the heart rate which allows the heart to completely fill (otherwise this isn’t happening like it does in healthy people). Admittedly I skimmed the article and comments, but isn’t this how Corlanor is treating me/cfs?

Regarding the change in muscle fibres and lowered aerobic enzymes, I had a very slow onset which started with a couple of patches of burning scalp muscles. Then eye problems of external muscles, mostly left eye. Followed by jaw, then left neck and onward down through adjacent muscle groups. It took three years to get to hips then legs. I used to say it feels like the muscles have gone through a transformation process and would be semi numb on the skin surface. I didn’t start to get PEM until most of the muscles were involved. Once involved they would be very quick to fatigue, but for a long time it was only upper body muscles.

Of course there are other factors involved, it all coincided with reducing hormones and peri menopause, immune factors – improvement in everything with the couple of colds I’ve had and the Pf v. So for me, muscle fibres/sfn are very interesting candidates

I describe ME/CFS as how you feel after a flu, but that you never recover.

It would be interesting to conduct these tests on other wise healthy individuals in such a post infectious state to parse out some of these effects.

I would suspect small fiber neuropathy to be a factor. I suspect also issues with cellular communications at the cell wall. I am uncertain how to best reference such an effect. Hyman’s Ultra Mind Solution gets at some of this science.

Hyman has an interesting approach to healing that I think has relevance to ME/CFS.

The hardest question is what is causing the decline in health resilience.

Of all Cort’s great write-ups, this one speaks to me the most. I’m another former athlete. My initial onset, was unexplained dyspnea after an upper respiratory infection which affected my exercise performance by ~5-20% depending on the specific workout, but not my daily life. Over time I developed “intermittent fatigue syndrome”: periodic slowdowns or crashes. But I always bounced back to the same modestly reduced performance level. As a fitness buff, the level seemed to me the proof I was healthy; and so I was focused on all sorts of explanations for what was causing the increasingly frequent crashes/slowdowns. Never in a million years did it occur to me that exercise could have been driving my condition worse.

I so hope that we’re getting closer. I was an avid exerciser as well. Anything to help explain the destruction of my ability to exercise without payback would be sooooo appreciated.

“Corticosteroid insufficiency results in decreased work capacity of striated muscle, weakness, and fatigue. This response reflects an inadequacy of the circulatory system rather than electrolyte and carbohydrate imbalances.”

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK13780/

I have had Fibromyalgia for a long time. I’m now 73 years old. As a result of a flu shot this year, I was catapulted into MCAS. I wouldn’t have known what was happening to me except that I had been reading this blog.

For years I have had burning muscles after even mild exertion, such as bending over to pick up something off the floor, but not with even brisk walking. In order to recover from the MCAS, I have had to go on a very strict diet and take a long list of supplements. These worked and I am now pretty stable.

One thing that really frightened me when the diet and supplements were beginning to work was that I thought I had become numb from the neck down. My brain seemed to be working better than ever, but not my body. It took me a few hours of walking around, moving my limbs, leaning over, etc. before I realized that I was not numb. The constant dull pain punctuated with sharp stabs that I had had for so many years was gone. And it has stayed gone. Many of my other fibro symptoms are also gone.

I know that fibro is one of the conditions that predisposes you to MCAS, but this has been brought home to me strongly with this experience. I guess progression over the years is indicative of the relationship between fibro, histamine intolerance, and MCAS. Furthermore, skeletal muscles are involved.

Ann, would you mind sharing what worked for you?

A key thing to note about this study is the strong statistical power. Although there were only 10 participants in each group, one directly measured variable (mixed venous oxygen percentage) fully separated the patients from healthy controls. The p-value was <.0001 even with the small sample size.

Seems to be heading towards truly decisive biomarker. Like PCR Covid test decisive. This one "just" requires a catheter.

One caveat in my own mind: perhaps this strong differentiation only applies earlier in the disease course for post-infectious exertional intolerance, i.e. those able to undergo iCPET (and most post-Covid patients given recentness). Across the pond, Dr. Asad Khan has described how he believes the opposite effect of low venous oxygen (which may roughly track mixed venous oxygen percentage) can also arise: when tissues go into a survival response and jack up their oxygen consumption. He's seen this in his case. So far the evidence for this seems anecdotal, but more may be coming out. Alternatively it may be because those tests are done at rest rather than under the well-constrained condition of peak exercise.

This article and especially the comments made my day. Having had me/cfs since 1997, it’s starting to feel like we are finally understanding what is happening to us. This exercise and muscle issue makes so much sense as relates to what I have been dealing with. There may be hope. At least understanding. Feels awesome

My cardiologist at university of Miami is going a study on endothelial function in long covid and in me I had marked deficiency in that only 1 of 6 tubes regrew in what they were testing, despite the brachial artery testing showing “normal vessel response”. I believe this fits in closely with what’s written about here. His solution to this is messenchymal stem cell therapy and he’s hoping to get approval for it once submitted. All of this however, depicts dysautonomia, which is the most common Dx in longhaulers which is therefor contributing to the cascading diagnosis effect many of us are all to familiar with.

Very interesting Karyn! Please keep us updated!

Cannot express how excited and hopeful I feel after reading this article and especially the comment thread with various experiences/expertise shared—thank you. Have had CFS dx 20 yrs ago (but not ME) aches and pains and chronic headaches yes–so not myalgia. And Epstein Barr (chronic form and had mono the infectious form as teen) 15 yrs ago the panel showed levels ‘through the roof’ beyond high ref range but have recovered ( based on current labs) with the help of a naturopath at the time. Had near every test from conventional specialists– nerve/muscle conduction, full cardio/stress test, and recent test for myelitis= all NORMAL. Unable to move legs up a stair or incline walking ( 15 + yrs)-like wearing lead shoes. Possibly fighting a virus maybe Covid (but asymptomatic and no dx) as interestingly in Sept the breathlessness, the fatigue so severe 4 solid weeks a 2 min walk to another room forced me to bed/prone to recover. Bed ridden but have recovered somewhat now. So many puzzle pieces. Former athlete tennis player. I do not expect any dx from my local docs but believe the tests described in article would elucidate my case. Do others have good results with drug therapy such as Mestinon, Colanor or antivirals? Thinking of asking PCP for a trial but do not expect she has heard of these/nor approve). Since there are many of us we should be included in a study (expanding on the ten person one) to forward understanding/teach medical professionals. I think the stem cell therapy promising. The deconditioning conclusion needs to be fully discredited and loudly debunked by the experts…Dr.Singh etc. Thank you very much for this article, the links too.

If long covid is an auto-immune disorder that results in micro-clotting in the capillaries would not this correspond with the findings here? For my LC I’ve tried many things that have helped, which now includes nattokinase and serrapeptase to help dissolve clots.

We would love to know what has helped you Dennis. Thank you!

This (Singh et al.) is a good study, though the discussion in the manuscript suggests authors don’t fully understand the relationship between group III-IV skeletal muscle afferent activity and ventilation. It doesn’t magically lead to hyperventilation, there are other key intermediate steps that mean that there can still be stimulation without hyperventilation.

I share the frustration with the blaming of longcovid on deconditioning – I honestly believe that many people conducitng CPET studies have almost no idea about the relationship between central and peripheral fatigue and how it is mediated neurologically. Very few pulmonologists actually understand the physiology that determines the ventilatory thresholds, for example. Anyway, deconditioning simply decreases peak performance, it isn’t a cause of fatigue in itself and anyone who actually understands exercise physiology knows this.

This sounds like exactly what’s been going on in my body for over a year and a half. I had COVID-19 in early March 2020 (at least I think so, couldn’t get tested), and since then have suffered from incredibly painful and exhausted muscles every time I overdo it. As a former exercise instructor, I was quite familiar with muscle pain after a hard workout, but this is nothing like that. I’m finally able to walk 3-5 miles a day (2-3 long walks with my dog every day in a hilly neighborhood). Some days I feel perfectly fine. But if I do too much without enough rest in between, or try to also vacuum the house or something, I still get that dead feeling in my muscles, get extremely out of breath during the walks, my heart rate soars, and then I’ll crash in bed totally fatigued for a couple of days. I’ve found I need to space out exercise, drink lots of water, avoid too much sugar or salt, and rest when I start to feel like I’ve got water in my lungs. I think I’m getting better, or maybe I’m just better at managing it all. At any rate, this explains everything I’ve been going through. Now, what else can I do to help things along??

Prior to acquiring Covid in April of 2020, I walked 3-4 miles a day at work, besides exercising. Now, after 18 months, I can walk slightly over a mile at a moderate pace. I’ve received no medical intervention other than routine pulmonary exams for asthma. What has worked for me is Qi gong. I do a very mild version that focuses on breath along with body movement, no floor work. After about 4 months of very basic Qi gong, my joint pain is mostly gone and I have gradually been able to increase the distance I walk. I am talking distance in feet, not miles, but it’s improvement. Doing the breath work is very challenging, even though it’s just a measured inhale/exhale, but my last PFTs came back at pre-Covid levels so it’s worth the effort.

Ties in nicely with this:

https://www.fau.eu/2021/08/27/news/research/further-patients-benefit-from-drug-against-long-covid/

It makes sense that micro-circulation could be impaired leading to the inability or difficulty of muscle fibers and even neurons to intake oxygen from the blood.

i have long covid symptoms from vaccine. had my 2nd dose pfizer jan2021. 3 days after i experienced shortness of breath, occasional palpitation and chest thightness. about 2wks after the shot i had appendicitis/appendectomy. shortness of breath and chest thightness continued..brain fog and muscle pain was added. since my lungs and heart were good, a cardiopulmonary stress test was ordered. unfortunately, i only lasted about 15min or less and i was almost to the point of passing out..my legs couldn’t do it, started hyperventilation, BP 190/ 130, chest hurting, body tingling; they were unable to do the 2nd ABG because they could not feel my pulse on my both wrist anymore. no explanation was given to me on why my body reacted that way. instead i got the “this number is good before you give up…” it’s upsetting bc i didn’t just give up. i could not do it. i was told by 5 doctors that im deconditioned and need to start exercising slowly. the problem is, i get short of breath just going up our 13 step stairs, heart rate goes up to120. if i do exert little effort, i’m literaly down for 1 week. it didnt help either that i became anemic.

i am feeling a little better now though since i was put on metoprolol (im also on breo and iron). it helped a lot, i think.

A classic case of long COVID/ ME/CFS – which doctors don’t understand (and thus go straight to the deconditioning card, Cecile. Hang in there! We’re going to learn a lot about these diseases over the next couple of years.

Hi cort , I subscribed and ended up back on this page when I was going to reply to you , I’m only new to this and trying to find my way 😊 that article was wrote about 11/2yesrs ago and wondering if there was anything new about it ?? And also if there are any new findings about anything else to do with CFS ??? 😇👍

Back in march of 2020 I got sick. no testing but was covid I’m sure. I was better in less than 2 days. But I was dragging. no energy. naps or sleep did not alleviate the fatigue. I had this idea that Iron was somehow part of the problem and took an iron supplement. Next day I felt so much better. But was afraid to over do it on the iron. So, I took 1 iron pill a week for a 4 or 5 weeks. The results always the same. Next day felt great, getting worse again over the next week. I decided to stop taking iron and while out on a jog I had an AFIB event. Everything went down hill after being released from the hospital. Adrenaline spikes for 20+ hours. Heart palpitations, irregular heart beats, muscle spasm and twitching, burning pins and needles. Blood tests were normal but inflammation markers were high. I tried to explain the iron and how it helped me. Every Dr. told me to stop with the iron. My brother a dr., then ordered an iron panel it was discovered my iron was rock bottom. I started the iron and made massive recovery but was still hit with brain fog. after several weeks of iron I stopped it again. and eventually heart palpitations returned. 24 hours a day. I started iron again and things would improve. Dr. told me to stop. this cycle repeated itself for 1.5 years. Until I said f this and started taking 1 iron pill a day. I think the combination of time and iron saved me. I wish they would investigate the oxygen problem related to iron.