Letting the Sun Shine In?

“Let the sun shine, let the sun shine in, the sun shine in,

Let the sun shine, let the sun shine in, the sun shine in”

From “The Age of Aquarius” by the 5th Dimension.

Yes – psychedelics, of all things, are now being trialed in fibromyalgia (FM) and chronic pain. If taking psychedelics to improve your FM sounds fanciful, weird, or fringy, think again. While it’s not clear these drugs may help, they are being taken seriously by academia. Some researchers even believe psychedelics like psilocybin and NMDA are just a few years away from FDA approval. Let the sun shine in, indeed.

In fact, as Michael Pollan points out in his fascinating book, “How to Change Your Mind: What the New Science of Psychedelics Teaches Us About Consciousness, Dying, Addiction, Depression, and Transcendence“, studying psilocybin and other psychedelics is not a new thing at all. More than a thousand papers were published in scientific journals before the backlash to Timothy Leary, the Sixties, and the CIA’s shenanigans essentially drove the drug underground.

The psychedelic boom all started, oddly enough, in a scientific setting in the late 1930s when a young Swiss chemist employed by Sandoz laboratories was tasked with plowing through the plant compounds found in a fungus called ergot. Ergot is a fungus that infects grains which can cause some people to appear to go mad, but it was ergot’s use as a labor inducer and bleeding stauncher that had captured Sandoz’s attention.

The discoverer of LSD – a chemist named Albert Hoffman – described seeing the world as if newly created. (Image by Gordon Johnson of Pixabay)

Hoffman’s efforts were to no avail until – and here’s where it takes gets a little woo-woo – five years later Hoffman, uncharacteristically, decided to return to a compound he’d discarded. Later stating that there was something he liked about its chemical structure, Hoffman returned to lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD-25) and retested it.

Hoffman knew that ergot could make people go a little crazy, so he was careful, but he must have slipped up somewhere and absorbed some LSD through his skin because he started feeling some unusual sensations which quickly evolved into a full-blown trip consisting of “fantastic pictures, (and an) extraordinary kaleidoscopic play of colors”.

Intrigued, Hoffman returned a couple of days later to conduct a little experiment – on himself – something that researchers often did back then. After taking what he thought was a minuscule dose of the drug (.25 mg in a glass of water) he descended into the first bad LSD trip ever recorded. As he watched familiar objects assume “grotesque forms”, the outer world “disintegrate” and his ego wash away, Hoffman worried that he was going insane. When he came down, though, he entered into a different world where “everything glistened and sparkled in a fresh light”. The world was, he said, “as if newly created”.

Hoffman was changed forever by his experience. The hard-bitten chemist became, as Pollan notes, “something of a mystic, preaching a gospel of spiritual renewal and reconnection with nature”.

Sandoz saw a different opportunity entirely. Noting how incredibly potent the drug was, Sandoz provided LSD (they called it “Delysid) free of charge from around 1950 to 1966 to thousands of research efforts at institutions like Harvard, Cambridge, and UCLA. Studies touted LSD’s effectiveness at relieving depression, alcoholism, anxiety, and obsessive-compulsive disorder. By the mid-sixties, LSD was being commonly used by psychiatrists in LA and London.

Articles appearing in Time and Life magazines in the 1950s made psychedelics a mainstream topic. It was a J.P. Morgan Vice President, no less, named R. Gordon Wasson, whose 1957 Life magazine article, “Seeking the Magic Mushroom“, ignited the masses. Wasson’s described experiencing harmonious visions in “vivid color” “that seemed more real to me than anything I had ever seen with my own eyes” during his trip on mushrooms in the mountains of Oaxaca, Mexico. (Albert Hoffman would later isolate the two psychoactive compounds responsible for Wasson’s trip – psilocybin and psilocin.)

The psychedelic/academia connection got snipped in 1966 when Sandoz – startled at the controversy the drug had elicited – withdrew the drug from circulation. After the US government banned LSD in 1967, and declared it a schedule I substance “with a high potential for abuse and no recognized medical use” in 1970, the drug went underground. Funding by the National Institutes of Health continued until the late 1970s, though, until the backlash from a Rockefeller Commission report which found that the CIA had been dosing both employees and civilians without their permission, shut down academic psychedelic research for decades.

A revival began in 1998 when Roland Griffiths at Johns Hopkins University was able to wend a psilocybin grant application past a boatload of concerned reviewers. Since then, Griffiths has co-authored dozens of studies on psychedelics and runs the Johns Hopkins Center for Psychedelic Research that’s staffed by about a dozen PhDs and MDs. In 2008 guidelines for safely studying hallucinogens were published. Since then, psilocybin and psychedelic research has gone quietly mainstream with hundreds of studies published this year.

Besides attempting to figure out how infinitesimally small amounts of a substance could have such mind-altering effects, most clinical trials are focused on attempts to relieve diseases like depression, anxiety, alcoholism, and PTSD. Some, however, are reaching further and attempting to alleviate symptoms in diseases like post-concussion syndrome, Parkinson’s Disease, cluster headache, and fibromyalgia.

A Chronic Pain Connection?

The fact that minute amounts of these drugs can produce such potent effects has sparked much interest in using them to understand how the brain works. We now know that these drugs and serotonin all have a tryptamine structure and that the compounds attach to serotonin receptors – particularly the 5HT-2A receptor. In fact, psilocybin attaches more effectively to the body’s 5HT-2A receptor than serotonin does.

We also know psychedelics affect the serotonergic neurons that impact parts of the brain that are involved in pain perception. Some believe that next-generation serotonergic drugs will be helpful in pain disorders like FM where the descending serotonergic inhibitory pain pathways are not working well.

In “Chronic pain and psychedelics: a review and proposed mechanism of action“, Joel Castellanos, a Scripps anesthesiologist, explained how psychedelics might be able to bring relief to pain sufferers, as well. One idea is that small doses of psilocybin might function as potent anti-inflammatories for the brain.

It’s a possible increase in neural plasticity, though, that psilocybin and similar drugs may bring which gets the most attention. Studies that characterize the transition from acute to chronic pain suggest that as neural plasticity declines some brain pathways kind of get stuck in a pain mode. Studies have found, for instance, altered activity in pain-associated networks involving the insula and anterior cingulate cortex in both fibromyalgia and ME/CFS.

Moving Beyond Your Past? Turning off the Default Mode Network.

The default mode network keeps a clamp on the brain’s activities. Drugs like psilocybin temporarily release that clamp allowing new connections to be made. (Image from Wikimedia Commons.)

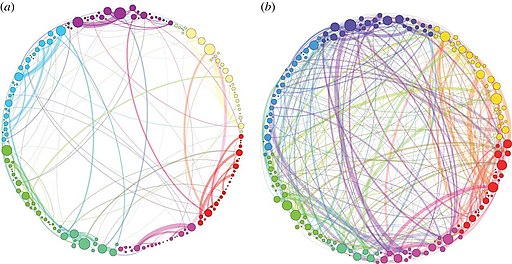

The default mode network (DMN) in the brain, though, may be the key. Several studies have suggested that something has gone wrong with the DMN in ME/CFS and fibromyalgia.

Studies have revealed that psychedelics temporarily break the hold the DMN has on the brain. The rumination center of the brain, the DMN lights up when our attention wanes. It also orchestrates and organizes brain functioning, and, perhaps most importantly for people with FM and ME/CFS or any difficult chronic disease, the DMN uses our past experiences to chart out our futures.

The ability of psychedelics to release the hold the DMN has on the brain may be what allows for the extraordinary experience that can occur. At the same time these drugs are reducing blood flows to the DMN they’re increasing blood flows to other regions of the brain. Meditation, interestingly, produces a similar reduction in DMN activity.

Because psychedelics have the potential to, as one researcher rather colorfully put it, ‘disintegrate’ existing brain networks and then open up new, more productive ones, they may be able to help get chronic pain patients’ brains out of their pain ruts. Another researcher proposed that psychedelics may provide the opportunity for brain network “resetting” and another suggested they may be able “lubricate cognition” in ways that enhance well-being.

Psychedelics, then, might be one way of increasing neuroplasticity. Neuroplasticity’s core thesis is that neurons that wire together fire together. The more pain neurons fire together, the stronger the connections they produce, and the more pain a person experiences. The process can be visualized as a river carving out deeper and deeper channels that take up more and more of the brain’s resources which become harder and harder to alter over time.

Not only does that process cause one’s pain to intensify, but it can cause pain to spread. Arthritis patients who later come down with fibromyalgia may be suffering from an amplification of their pain-producing brain networks.

By breaking down old and unhealthy brain pathways and opening up new connections, psychedelics may be able to do more quickly what neural plasticity programs like the Amygdala and Insula Retraining Program, Dynamic Neural Retraining System, and Dr. Moskowitz’s approach accomplish.

In fact, one wonders if psychedelics done judiciously could boost the efficacy of these neural plasticity programs and vice versa. Engaging in neuroplasticity programs and practices like meditation might even prove critical in maintaining the new connections formed during the psychedelic experience. Meditation practices are often used in psychedelic retreats and studies to amplify and support the psychedelic experience.

The Future

The impact psychedelics may have on pain is mostly speculation at this point. Study evidence dating back to the 1950s suggests that psychedelics may be quite helpful in pain, but only a few modern studies have been done.

Several chronic pain psychedelic studies are, however, underway. (Note that these studies use standardized techniques to ensure that a safe experience occurs.) Tryp Therapeutics is partnering with one of the largest FM research centers in the country Daniel Clauw’s Chronic Pain & Fatigue Research Center in a synthetic psilocybin study.

Stating that “existing treatment options for fibromyalgia are often ineffective and show significant side effects,” Clauw well knows how ineffective the current treatment options are for FM. A longtime FM researcher, Clauw has stated that he would welcome cannabis studies if the federal government wouldn’t put up so many roadblocks. Now, his Center has signed on to a psilocybin study. Find out more about the study here.

Another study at the University of Alabama at Birmingham will use .36 mg/kg of psilocybin in the expectation that the participants will have “a full mystical-type experience”. (A series of preparatory sessions will ready the participants for their experience). Johannes Ramaekers of Maastricht University is also reportedly developing a fibromyalgia psychedelic pain study.

A Stanford Neuroscience Newsletter reported that a psychedelic-inspired start-up called Mind Medicine (MindMed) has begun “Project Angie” which will involve a series of studies using LSD (and an undisclosed drug) to treat pain. The company stated that “preliminary evidence” suggested that psychedelics may offer “an entirely novel mechanism of action for treating pain”.

Yale University is also trialing psilocybin in cluster headaches – one of the most painful diseases known. These headaches have been described as being more painful than childbirth, getting shot, or passing a kidney stone. Yale reportedly got interested in psilocybin after a cluster headache sufferer at the end of his rope found relief when microdosing with psilocybin. Other cluster headache patients have found microdosing helpful as well.

Outside Academia

Of course, people outside academia are experimenting…

Microdosing – No Tripping Required

If a full-blown, mind-altering experience isn’t your cup of tea, microdosing might be a possibility. Microdosing involves using doses of psilocybin low enough to increase one’s awareness, alertness, energy, and calmness but without causing one to trip.

Microdosing apparently took off a couple of years ago when Tim Ferris, the author of The Four Hour Workweek, interviewed Dr. James Fadiman, Ph.D. on his podcast. (Check out the podcast here – Episode #66: The Psychedelic Explorer’s Guide- Risks, Micro-Dosing, Ibogaine, and More).

Fadiman is the author of the 2011 book, “The Psychedelic Explorer’s Guide: Safe, Therapeutic, and Sacred Journeys“. Fadiman apparently uses microdosing for “problem-solving purposes”, but others use it to feel more relaxed, to be more “in the flow”, to increase their alertness and energy levels, etc. A microdosing study at Imperial College, London, is reportedly underway.

A recent study found that LSD given at doses below those which produce profound mind-altering effects reduced pain levels to a similar extent as drugs like oxycontin. A 2019 review, “Microdosing psychedelics: More questions than answers? An overview and suggestions for future research“, though, emphasized how little we know about the health effects of microdosing.

- Check out microdosing websites here, here, and here.

- You also might want to check out Nicole Kidman in the Nine Perfect Strangers series for a fictionalized account of a Wellness Institute called Tranquillum that employed psychedelics (without informing its clients first).

Psychedelic Retreats

Other groups offer curated psychedelic experiences at retreats. Eleusinia, for instance, which caters to those with painful illnesses, uses virtual reality headsets and meditation in its four-day “psilo retreats” off the coast of Mexico. At the end of the course, the participants are given instructions on how to grow their own mushrooms. Many others are available.

Find out more about psychedelic retreats here and here.

Conclusion

It will take some time to know if psychedelics like psilocybin offer a novel and new approach to chronic pain conditions like fibromyalgia and ME/CFS. Much remains to be learned about dosing, long-term effects, etc., but the research community is engaged and studies are underway. Some researchers believe it’s just a matter of time before some psychedelics get FDA approval. Let the sunshine in, indeed.

Take the Poll

Big Little Donation Drive Update

Thanks to the over 125 people who have supported Health Rising’s year-end fundraising drive! This psychedelics blog exemplifies some of the things Health Rising is all about: digging through the weeds to find unconventional treatment options, uncover why they may (or may not) work, and updating you on what’s happening in the field.

If you appreciate that kind of commitment, please support Health Rising!

Interesting. Has anyone ever surveyed disease prevalence amongst the recreational user communities (Deadheads etc.)?

“Despite the difficulty of designing proper double blind clinical trials with this substance,”. I would imagine.

Hi Lono,

The thing is, recreational use often doesn’t go any deeper than that. To generate deep healing, create new neural pathways etc, one has to do the work beforehand, and after (integration), to be aware of his own erroneous conditioned beliefs, limiting fears, past traumas etc. Set and setting is especially important: alone or with a trusted friend, with an appropriate palylist, and eyeshades. People using psychedelics in a festival, with a bunch of strangers around them, that is not exactly the perfect setting for deep healing.

Done that. Helps, but you can’t take it every day or it stops working. So you only have benefits two days a week. I’m just hoping that those good things happening in my brain are building up over time.

Easy if you’re in Canada. Lots of websites sell it and there is no enforcement. Those in the know say it is heading for legalization here like cannabis was.

BTW, CBD is a very strong anti-inflammatory and helps my MCAS.

KETAMINE with psychotherapy is legal and can be effective when used responsibly in a clinical setting. However, we need to remember Jack Kornfield :

“After the ECSTASY, there’s the laundry”

The key is how we integrate the insights into our everyday life.

You might be interested in the DMT studies of Dr. Ede Frecska and his colleagues. I tried DMT, and it seems to help with brain fog, but its so intense and illegal that I’m not looking forward to do it again. On th eother hand its short duration (5/10 min) makes it more appealing for ME patients than long mushroom trips, let alone lsd.

i forgot to add the link to the works of Dr. Ede Frecska: https://dmtquest.org/dr-ede-frecska/

Justin, hi! Thank you for the link ! I came across a few recovery testimonies (from people who had CFS) on the DMT-nexus forum, and on Reddit. DMT is a very interesting substance indeed. I need to read “The spirit molecule”. I plan on trying it if I don’t get any breakthrough from psilocybin.

There is a body of closely related research using ecstasy, mdma.

The mechanism of action is theorized as via the hormone oxytocin and increased parasympathetic activity.

https://www.harperwave.com/book/9780062862884/Good-Chemistry-Julie-Holland/

As I recall the author/researcher is in Eastern Upstate NY, with her husband they do an awesome presentation.

In general this class of research has dealt with similar biases to those in ME/CFS.

I’ve had good luck microdosing mirtazapine on my own. If I take about a half mg before bed my sleep is better, pain is less, no leg cramps and no hung over effect the next day. The prescribed 7.5mg is aweful and even though 15mg is supposed to be less sedating, why would I take that when .5mg works fine?

I’ve had some benefit from microdosing mirtazapine too, but for me the downside is weight gain and obsession with eating (and trying not to). I am very curious about microdosing psychedelics, have not tried that.

Relieving pain in fibromyalgia sounds promising, but I would be hesitant to try psychedelics with ME. Tripping doses seem especially a bad idea because I thought they came with a high fever. Seems like they could put you directly into a relapse, risking the brain injury that goes with that. Maybe microdoses would help, especially if they really did suppress brain inflammation in ME. And I would try it in a study. It’s definitely not something I would try on my own. The low-dose abilify is working well for me at keeping my mind clear and reducing brain fog, presumably by reducing brain inflammation. This is a worthy treatment goal, but I didn’t see anything in the psychedelic literature that would directly impact the underlying causes of ME, presuming they’re autoimmune mitochondrial problems. So I’m in the “not sure” category in your survey.

Using Cannabis To sleep and reduce neck and shoulder pain which is effective, it works like muscle relaxers, but i an only use it at night. I can imagine we are talking about similar effect. It remains dealing with pain and fatigue during the day.

This is the most hopeful thing I’ve read about pain research. I’ve had fibromyalgia and myofascial pain syndrome for decades and more recently (last 4 years) have also experienced occipital neuralgia. Unfortunately, I cannot tolerate any medication that has codeine in it (causes severe nausea) so I’m limited to morphine sulfate for pain control. The amount required continues to increase, so I’m very eager to have an alternative become available. Thanks for keeping us informed.

Hi Christine, wow, I am sorry to hear about your struggles! Have you been able to try psychedelics to address those issues ? Psilocybin is quite popular among the “cluster headaches” community, I have alos read of people finding relief from all kinds of chronic pain. Keep us posted, I am curious to know how you are doing now 🙂

I would be very interested to try microdosing psilocybin but I’d want to be sure of the size of the dose, its safety and quality. I cannot see how one can obtain them and find this information legally or illegally.

Here in the UK, we have fewer options compared to the US. This is because medicines have to be approved by NICE. This is all well and good and is an important safety measure, but NICE takes forever to look at and approve anything. For example, we have fewer antidepressant options than people in the US. We cannot be prescribed Wellbutrin which seems to help many people in the US. According to the NICE website, the manufacturer of Wellbutrin has not provided enough evidence of safety. If this is truly the case, then why not? Thought you’d all like to know in the US!

Despite doctors in the UK being given permission to prescribe Cannabis for serious epilepsy (and pain I think?), the constraints and qualifications announced by NICE mean that only specialists can do this and very few do. They think there is not enough evidence to support its use.

I would like to try cannabis (the full drug) but we can only legally obtain CBD (without THC) here at great expense and that does nothing for me. It is illegal to grow it or your own use. I have hopes that microdosing well-known hallucinogens might really help with depression and pain, but I want to do it safely.

I know it is possible to obtain some of these drugs online (and illegally) here in the UK – if I want to take the risk of it being stopped at Customs – but there is no way to guarantee the safety. That is why we need NICE to study these drugs and maybe even allow the use of tabs in microdoses. Some of us feel we have very few options for depression and pain and now that the NHS is breaking under the strain of Covid and only able to treat emergencies, many of us are desperately trying to find ways to help ourselves.

Hi Joolz! There are several Facebook groups (and books) about microdosing, macro dosing, etc. Just do a quick research, one of these groups is called “microdose”: https://www.facebook.com/groups/microdose/

Joolz….you need to talk to a friend of a friend of a friend to find mushrooms…or…go on Facebook…there are several Facebook groups that will secretly help you obtain mushrooms…safe mushrooms

Quick comment—you’ve got a typo:

Pretty sure you meant “MDMA” not “NMDA”. NMDA is an amino acid that acts as a neurotransmitter at the NMDA receptors. Ketamine is a well-known NMDA-receptor antagonist. MDMA is 3,4-methylene dioxymethamphetamine (“ecstasy”).

Thanks for the intriguing article.

If microdosing can relieve pain without negative consequences, it could be a much better alternative than the opioids that are killing so many. I know there is research using psychedelics helping depression. We shouldn’t allow our puritanical values get in the way of progress. In the ’60s these unregulated drugs caused some young people to jump out of windows or walk into traffic, and that is why they were shut down. If they can be regulated and used to enhance the quality of life for those that suffer without addiction, they could be a boon to healthcare. Maybe Timothy Leary was on to something.

Anything that the US can’t easily tax or the drug manufacturing buddies of high ranking can’t produce artificially, is illegal. You mentioned people jumping out of windows and walking into traffic but alcohol causes people to do both. It also causes one to not only hurt themselves but others as well.

HERE HERE

I did a bunch of ayahuasca ceremonies and didn’t have any relief of anything except my mood was improved, however it did seem to make my POTS worse for several weeks after each ceremony. I was having a lot of increased tachycardia even if I was feeling a big boost in mood. And I did them before I was officially diagnosed with POTS as well, and even though mine isn’t as severe as some people’s I had bad chest pains at times during the trips and the shamans/curanderos had to attend to me.

Thanks for this article. I tried mescaline, lsd, and psilocybin a handful of times in the ’70s, and the only one I liked was psilocybin. It shifted my worldview.

I’m very interested in microdosing. I followed all of the links, and it’s unclear if I could buy psilocybin in one of the cities in the US where it’s been decriminalized. My guess is that I would have to prove that I live there, but does anybody know?

Exciting to see this approach making progress.

Also, a fun historical tidbit: these days we’re all used to casual mentions of PCR but many consider it to have revolutionized molecular bio. Kary Mullis, the primary inventor of the technique, attributed key “eureka” moments to his use of LSD and other psychedelics.

🙂

The inventor of the PCR test, Kary Mullis, explains that someone who tests positive for a virus does not have to be sick and/or contagious. If you search long enough and magnify each particle infinitely, you will always find something. And that says NOTHING. What does this say about a positive corona test? This means that there can be a lot of false positive tests.