The focus on using male animal models meant pain researchers didn’t realize that pain was produced in a very different way in the people most at risk from pain – women.

Despite the fact that some have postulated men and women come from different planets, the medical profession has long assumed that when it comes to biology men make a fine stand-in for women. That attitude has been steadily changing and a brilliant Canadian study suggests it’s about to change even more.

The study put a stamp on something that’s been pretty obvious for quite a while: when it comes to pain, vast differences exist between the sexes. The most basic stats show it. With men and women pretty evenly split in the population at large, women make up about 70% of chronic pain sufferers – suggesting they are more than twice as likely to come down with a chronic pain disorder than men.

Despite experiencing more pain, women tend to be less effectively treated for pain. A Harvard Health blog, “Women and pain: Disparities in experience and treatment“, reported when they are in pain, women are much more likely than men to receive a sedative (a sedative?) instead of a pain killer. One study suggested they were much less likely than their male counterparts (who are presumably in less pain) to be prescribed painkillers after surgery.

Women-dominated disorders such as fibromyalgia (FM), chronic fatigue syndrome, endometriosis, migraine, and interstitial cystitis top the list of most neglected and poorly funded diseases. Despite the fact that about one in five Americans lives with chronic pain, we’re still lousy at treating it. Our main mode of treatment – opioids – are designed for short-term use. Several reasons can explain why – despite the huge market opportunity staring them in the face – pharmaceutical companies have proven so ineffective at delivering safe and effective treatments for pain.

For one, as one might expect given its central role in alerting us that something is seriously wrong and the emotions that come with that – pain is a very complex phenomenon that engages large areas of the brain and is affected not just by the extent of a physical injury but by our emotional state (affective pain) as well.

For another, pain researchers have been like the person hunting around for his/her lost key at night by looking only where the streetlight is shining. What pain researchers have failed to grasp until recently is that their working supposition – that pain circuits are simply more amplified in women – is wrong. It turns out that basic parts of our pain circuits also work differently in men and women. Ironically, the very reason that researchers avoided female animal models – the complexity that female hormones introduced – turned out to play a key role in how their bodies process pain signals.

When it comes to pain, women and men really do, in some ways, come from different planets.

Landmark Canadian Paper Finds

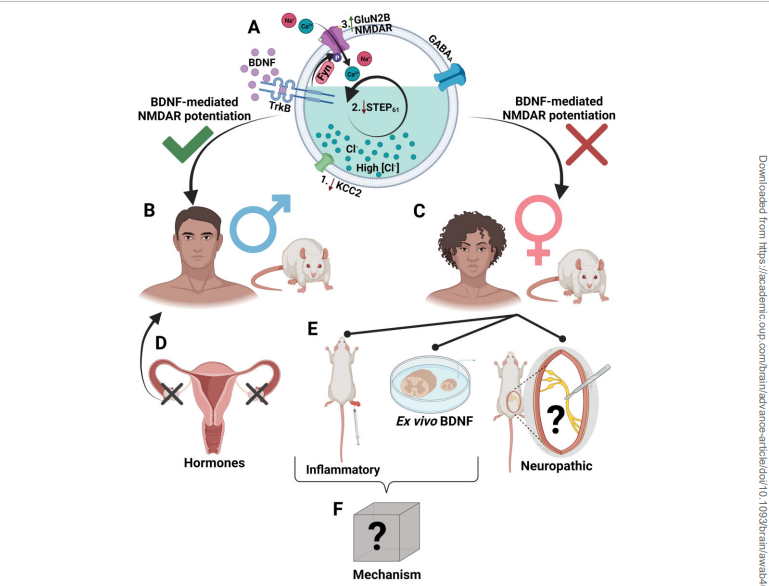

This was demonstrated by a recent Canadian study, “A sexually dimorphic neuronal mechanism of spinal hyperexcitability in rodent and human pain models”, which is being hailed as a landmark in the understanding of how pain at very deep levels is processed differently in men and women. Of course, it starts with rodents. (It almost always starts with rodents).

The authors wanted to know what happens at key locations in the pain processing process – at the dorsal horn of the spinal cord – in male and female rats. The dorsal horn outside the spinal cord processes information from sensory and pain signals from across the body and sends it onto the spinal cord. It’s been shown to play an important role in pain amplification in chronic pain – including fibromyalgia.

Using new technology, they also took spinal cord tissue from male and female autopsies and tested it.

Results

BDNF excites pain-producing nerves in dorsal horn neurons outside the spinal cord in men but does not do so in women. CGRP may play that role.

Past studies on male rodents found that a protein called BDNF (brain-derived neurotrophic factor) sends NMDAR (N-methyl D-aspartate receptors) receptors on the neurons into a tizzy, jacking up the pain signals going to the brain.

This study found that as well but only in the male rodents. A pathway involving receptors other than the NMDARs was at work in the females, and the presence of BDNF had no effect at all on that pathway or the pathway upregulated in the females.

Human spinal cord tissue displayed the same pattern – the male spinal cord tissue responded differently to a triggering substance than did the female spinal cord tissue.

Everything changed, though, when the rats’ ovaries were removed early in their lifespan. Absent their ovaries, the female rat spinal cords behaved exactly the same as the male rats’ spinal cords did. A hormone produced by the ovaries had somehow changed how pain was being produced in the female rats.

The authors noted that their study indicated how little work has been done on pain amplification in females in its the very early stages as pain signals get processed in the dorsal horn neurons. Some other signaling pathways or immune mechanisms which could conceivably be toned down – are at play in fibromyalgia.

In fact, the first chronic pain disease the authors noted in this regard was fibromyalgia, where studies have shown that two spinal cord pain responses – the nociceptor flexion response and windup have been amplified.

Given the switch in pain signaling that appears to occur with the development of the ovaries, and the huge hormonal shifts that occur during puberty and menopause, the way is now open to determine how alterations in estrogen and progesterone production affect pain signaling over time in women.

Gender and Sex Hormones in Fibromyalgia and Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS)

Evidence – direct and indirect – already abounds that sex hormones play a role in ME/CFS and FM.

The greatly accelerated risk females have of coming down with fibromyalgia or chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS) at puberty points an arrow straight at the hormones. That big gender gap often alluded to in ME/CFS/FM is missing in children. Boys and girls appear to have an equal risk of coming down with these diseases, until they hit puberty, when the risk for girls skyrockets. Women with ME/CFS/FM have also reported experiencing significantly improved pain and fatigue levels during pregnancy.

A 2011 CDC study found elevated levels of gynecological disorders and surgeries in women with ME/CFS. The authors hypothesized that “at any age, reduced or out of balance levels of gonadal hormones may contribute to the development of CFS symptoms” in various ways including impaired sleep, the loss of the neuroprotective effects of progesterone and estradiol, increased inflammation, increased pain sensitivity and impaired healing and repair.

The supercomputer models developed by Gordon Broderick and Travis Craddock at the Institute of Neuro-Immune Medicine (INIM) suggest that hormones may play a critical role in who gets these diseases, and have developed personalized treatments for ME/CFS and Gulf War Illness that are gender-based.

The models find that higher testosterone levels in men are protective. They suggest that the system of a person with high Th1 cytokine and cortisol levels, and low testosterone levels, could be returned to normal by combining a cytokine inhibitor Enbrel (etanercept) with a glucocorticoid inhibitor (mifepristone). Note that the high Th1 cytokine/cortisol/low testosterone model only applies to women.

In a small but intense study, Jarred Younger measured testosterone, progesterone, estradiol levels, and cortisol levels in 8 women with FM for 25 days straight while having them record their pain levels. He found that both progesterone and testosterone were inversely correlated with pain levels; that is, the higher the FM patients’ progesterone and testosterone levels were, the lower their pain was.

Progesterone level fluctuations, by themselves, appeared to affect pain levels by about 25%. Interestingly, neither estradiol or cortisol levels had any effect on pain except when progesterone levels were low. The biggest hit came when women experienced both low progesterone and high cortisol levels, and the most intense pain levels were associated with the menstrual period when sex hormone levels were at their lowest.

Younger noted that this was the first time pain levels and sex hormone levels had ever been tracked on a day-to-day basis in humans, but a very large (@10,000 person study) also found that lowered sex hormone levels (estrogen, testosterone, androstenedione, and 17-hydroxyprogesterone) were associated with an increased prevalence of chronic musculoskeletal pain.

Note that testosterone levels were implicated in two of the above three studies. We usually associate testosterone with “male vitality”, hairy chests, and deep voices, but Hillary White, Ph.D. has asserted that testosterone plays a key role in reducing stress in women.

White notes that stressful situations usually reduce pain levels (probably so that we can cope with the situation at hand) but that the opposite tends to occur in FM. This stress-reduction process occurs when substance P converts testosterone (male hormone) to estradiol (female hormone) which then upregulates the production of the endogenous (self-produced) opioids that cause pain relief. (Some studies suggested that the feel-good endorphins are reduced in fibromyalgia.)

White believes the lower testosterone levels found in FM (and other pain disorders) prevent this inhibitory pain network from functioning properly. Once that inhibitory pain network goes off the rails, pain sensitivity spikes higher and higher, and instead of stress reducing pain, it provokes it.

In two studies, Hillary White Ph.D. used testosterone gel to successfully reduce pain in fibromyalgia. Her testing revealed that the blood testosterone levels of the women entering the study were in the lower half of the normal reference range for their ages. Using the gel normalized, and slightly increased, their testosterone levels to just above the reference range. (The gel does not appear to be FDA-approved.)

A third of the women reported a 50%, or greater, decrease in pain. Forty-two percent were reported to have a 33%, or greater, decrease in pain. Tender point sensitivity was significantly reduced. Libido was significantly increased. The treatment had no effect, though, on headache severity, sleep, anxiety or depression. White also found reductions in fatigue and has proposed that her testosterone gel can help with the intractable kind of fatigue found in chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS).

The Gist

- Despite the fact that women make up the bulk of chronic pain sufferers, researchers – citing the complexity introduced by female hormones – have mostly used male animal models to understand pain.

- Researchers assumed that the same pain processing system was operating in both women and men but was simply getting amplified in women. It turned out that they were wrong. Ironically, their decision to exclude female animals – with their more complex hormonal dynamics – from their experiments prevented them from understanding the crucial role female hormones play in processing pain.

- This Canadian study, which used both an animal model and human spinal cord tissue, found that at a very basic level men and women process pain signals differently.

- The study found that a substance called BDNF – which has been studied extensively in fibromyalgia – jacked up pain signals at a key pain processing site in men but not in women.

- The dorsal horn neurons studied process pain and sensory signals coming from the body and send them through to the spinal cord. Studies have found that the dorsal horn neurons are one of the places where pain signals get amplified in fibromyalgia.

- Removing the ovaries early in the animals’ lifespan caused the female animals to process pain in the same way as male animals did. That indicated that female hormones are altering the way women’s bodies process pain.

- That’s quite interesting given that a similar female hormone-mediated process appears to be occurring in ME/CFS, as the risk of coming down with it jumps dramatically once girls reach puberty.

- Increased rates of gynecological disorders, the reductions in pain sometimes seen during pregnancy, supercomputer models which implicate both female and male sex hormones, and studies that suggest that sex hormones affect pain sensitivity and that testosterone might be helpful in women with FM all underscore the role that sex hormones seem to play in ME/CFS/FM.

- While the trigger for increased pain amplification for women is not known, the authors noted that their findings should ultimately open the window for better pain treatments for women.

- If their suggestion that CGRP is the mysterious “X” factor proves to be correct, FM patients could look to the recently produced anti-CGRP drugs for help. A large anti-CGRP treatment trial is underway in FM.

- Another large promising FM clinical trial underway involves ketamine.

Small Does Not Mean Not Creative – More Reasons for Long-COVID Patients and Researchers to Embrace ME/CFS/FM

(This is part of a continuing series that points out how ME/CFS/FM research may be helpful for the long-COVID community.)

The Younger, White, Klimas, and CDC studies provide more reasons why embracing ME/CFS/FM research and the ME/CFS/FM community at large makes sense for people with long COVID:

- Younger’s hormone study was the first to assess day-to-day fluctuations in hormones in chronic pain

- White proposed a novel and possibly effective treatment for chronic pain

- The CDC study demonstrated higher rates of gynecological problems are associated with ME/CFS

- Nancy Klimas’s supercomputer models suggest that sex hormones play a key role in the development and treatment regimens for people with post-infectious diseases.

Thus far, the long-COVID field has had its attention elsewhere. Despite evidence that long COVID affects women more than men, and that women are more severely affected by long COVID, I could find only one short paper that proposed that sex hormones may play a role in coming down with long COVID

New Treatments Envisioned

Understanding that pain signals are processed very differently in men and women opens up the possibility of finding more effective pain treatments for women. The lead researcher of the study, Annemarie Dedek, PhD, stated:

“Developing new pain drugs requires a detailed understanding of how pain is processed at the biological level. This discovery lays the foundation for the development of new treatments to help those suffering from chronic pain.”

The senior author of the study, Michael Hildebrand, reported: “These findings have big implications for treating pain in the clinical population. They suggest that in the future, sex may play a role in deciding what analgesics will be prescribed to patients. They may also lay the foundation for discovering new pain therapeutics that will work specifically on the female pain pathway.”

The authors noted that a potentially encouraging candidate for the “X” factor that’s amping up the pain signaling at the spinal cord in women is the calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP). Low doses of CGRP were found to induce pain hypersensitivity only in female rodent models of migraine. Plus, a possible hormonal connection – prolactin – has also been found in those models.

A CGRP connection to chronic pain production at the spinal level is potentially very good news for people with fibromyalgia given the recent explosion of anti-CGRP drugs in migraine – and the large anti-CGRP trial that’s currently underway in fibromyalgia.

Because NMDA receptor activation enhances pain levels in both men and women, damping down the activity of those receptors provides another option. The authors noted that NMDA receptor inhibitors like amantadine, ketamine, and magnesium can be helpful. Here again, a large ketamine study that’s currently underway in fibromyalgia provides another potential treatment option.

Keep the news flowing- support Health Rising

Keep the News Flowing – Support Health Rising

Think about it – where else would you have ever heard about the role sex hormones may play in ME/CFS/FM? Please support us and keep the news flowing!

Is this for real? (rest of the comment deleted).

Oops! I deleted the passage in the comment because it was a joke between me and editor (lol) – which was not supposed to be in the blog.

Oh thank you! I’d stopped reading after that paragraph and wondered if I’d ever be able to read anything from you again !

That was pretty wild…

I was wondering the same thing.

Citing the comment from Sumitra, this can’t be real. Would Canada really do that to humans?

They wouldn’t. I really apologize. It was a tongue-in-cheek joke with my editor that we forgot to delete before the blog came out.

I would have my ovaries removed in a heart beat if that would help. Thanks for another inspiring article that help is coming!

RIght. That’s an interesting question. I wonder if the system kind of gets set early or if it can be changed later on by something like that. The best thing might be to keep the hormones as they are and turn off the switch at the dorsal horn and tamp down the signal there.

Yes I wondered if that was true too!

It’s very hopeful to see research that delves into the sex differences found in pain. I recall reading about the research disparity decades ago – it’s shocking that this kind of research is still not *always* done. Excellent to see it here! It will be helpful to both women and men.

I just read that as of 2011 that the vast majority of animal studies were still using male animals. I imagine that’s changed quite a bit.

Is there any testosterone gel available to purchase? (Referring to Hillary White, PhD success with reducing chronic pain.)

Thank you for all you do! You’ve become my lifeline!

I don’t know but I imagine that a prescription is needed. The testosterone issue is interesting for me as my recent testosterone tests – which my GP unexpectedly asked for – show me to be in the low range. I hope I can give it a shot 🙂

“The gel used for this study was a 1% w/w testosterone gel, USP grade. The daily gel dose applied to the lower abdominal skin was 0.75 g of the 1% w/w testosterone gel; an expected bioavailability of 10% would deliver 0.75 mg testosterone over 24 h.”

Unfortunately, testosterone gel is a scheduled, controlled substance in the US which requires a prescription. The good news is that it is relatively inexpensive for a pharmaceutical product.

I’m curious, does menopause enter into this theory at all? I am well past menopause and have long Covid/ME/CFS but significant pain is not a big symptom for me, except for neuropathic pain. As far as I know, rodents don’t experience menopause.

I believe there are two peaks in ME/CFS prevalence – at puberty and around menopause – so yes, while menopause may or may not affect any one person’s symptoms, overall I would think menopause would be a factor.

Thanks Cort, I did not know that there was a peak around menopause, most statistics I’ve seen seem to point to younger people being most at risk. My first bout of an ME/CFS-like illness came soon after passing through menopause. At the time I was diagnosed with ‘Post Viral Syndrome’, which my doctor said was what they called it before you reached the 6-month point. I seemed to recover right around 6 months, had 11-12 very good years before my second and later third bout of it. This time around (4th and probably final bout), it’s lasted over 1.5 years so I’m officially diagnosed with ME/CFS. I believe this current illness is due to having Covid in the spring of 2020 when I was unable to qualify for testing. Again, I appeared to recover after a month of relatively mild illness, only to be suddenly and utterly felled by long Covid in the fall. I no longer hold out hope of recovery.

Hang in there, Anne! You never know what the next year or so will bring 🙂

I love this information! Thank you! It taught me so much and makes sense when I apply it to my 30 yr journey with my Chronic Intractable Spine injury related Pain and my Systemic Lupus symptoms, and some odd hormonal labs reports along the way that doctors could never figure out. This article helps ‘me’ figure it out a lot!

🙂