With its more remarkable funding, the NIH should be leading the hunt to solve long COVID. Thus far, though, it’s in the rear of the pack.

The NIH’s history with post-infectious diseases like chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS) carries so much baggage, and is so loaded with upset and so many years of unfulfilled expectations, that it’s hard to be objective.

Here are some central facts, though. The NIH’s massive budget – now over $40 billion/year – means it has the power to dictate the kind and scope of medical research that’s taking place worldwide. Compare the $26 billion the NIH spent in 2016 to the $3.7 billion the European Commission and the $1.3 billion the U.K.’s Medical Research Council spent on medical research funding and you can see why what the NIH does or doesn’t do matters so much.

Getting a program like the RECOVER Initiative up and running quickly was always going to be a stretch for an institution like the NIH.

We know that a bill to give the NIH $1.15 billion to study long COVID passed in December 2020. We know the long-COVID Initiative was going to be a stretch for the NIH. Quickly starting up a huge new program to study an entirely new condition in a field (post-infectious diseases) the NIH had devoted basically no resources was never going to be easy.

Walter Koroshetz, the director of the National Institute for Neurological Disorders (NINDS) certainly believes so, stating, “You can’t believe what a big lift this has been,” and that the RECOVER Initiative “is engineered to really not leave any stone unturned”.

Of course, when you’re given over a billion dollars to study something, there better not be any stones left unturned – and you had better show results – and it’s that little results thingie that’s recently become a problem. Congress put the NIH on the clock big time with its big shot of funding – and the NIH really needs to show that it can get this right. Thus far it hasn’t.

Doddering Institution?

It’s become something of a punching bag of late. A recent Atlantic article, “The Missing Part of America’s Pandemic Response,” was aimed at guess who? Calling the NIH sclerotic and overly cautious, the authors – one, a former department chair at the NIH, and the other, a professor of epidemiology at Yale – went to town on an institution that they believe largely sat out the biggest health crisis to hit the world in 100 years.

Called the NIH a doddering tired institution, the authors noted that of the 40 published clinical trials of hospitalized COVID patients, the NIH – by far the biggest medical research funder in the world – funded only a handful.

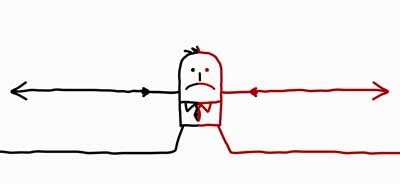

Two critics called the NIH a “doddering, sclerotic” organization.

According to these authors, the NIH looks like a stick in the mud compared to, believe it or not, its counterpart in the UK, which with a medical research budget 1/8th the size of the NIH – better rose to the pandemic challenge than the NIH did. “Starting with less than $3 million – yes, million” – the authors hastened to point out, “not billion” – the U.K. COVID-19 study “began enrolling thousands of patients almost immediately” across 170 hospitals. Forty-seven thousand patients have been enrolled and 15 treatments have been assessed.

The authors slammed an NIH peer review system that, by its very nature, rewards established labs and studies that produce predictable results while ignoring more creative research (not to mention blocking up-and-coming diseases like ME/CFS and fibromyalgia). The authors minced no words when they asserted that the researchers who man the critical peer review panels “have no incentive to expand the range of research topics or reward new approaches that might eclipse their own laboratories’ work.” Ouch!

A recent critical STAT News article echoed those critiques, stating that the NIH’s system awards older, whiter researchers at elite institutions that wield too much influence over the agency. A former NIH director stated, “The NIH leadership — like me — is too old, too white, and too male to be the group that guides them into the future,”. He called for many Institute directors to join him in retirement.

In a piece focused on the “identity crisis” Director Francis Collins’s departure has left the NIH in, STAT News considered that the NIH has a once-in-a-generation opportunity to produce major reforms. Even Collins has acknowledged that the NIH has become too conservative; that it’s likely to reward well-written grant proposals from major labs that, at best, will only produce incremental rewards over more risky proposals, which if they worked out, could produce amazing results.

The emergence of the long-COVID RECOVER Initiative gave the NIH a chance to show that it can think on its feet and respond quickly to a legitimate health crisis. I would bet that the RECOVER Initiative’s successes and failings are informing the search for the next NIH director. So far, it hasn’t worked out so well. In fact, it’s eerie how similar themes have emerged between the NIH’s failure to respond to ME/CFS and its failure to respond to long COVID.

If any disease group had reason to watch the NIH’s progress on long COVID, the ME/CFS community did, and it was heavily involved in advocating for long-COVID funding. The unforeseen breakthrough in long-COVID funding – $1.15 billion – promised much.

If we thought – as I did – that we were on an easy street after that, reality eventually intruded. There was, after all, this little group called the NIH to deal with.

Wretched History

The NIH that had never shown any real interest in ME/CFS or any other post-infectious disease. The NIH that ME/CFS researchers – who had achieved success in other fields – had given up trying to get grants from because of the overt bias they felt emanated from that organization. The NIH that as recently as 10 years ago was providing $6 million in funding for a disease that afflicts $1-2 million people in the U.S. The NIH that recently returned an Abilify grant proposal back to the applicant stating that all ME/CFS patients needed were antidepressants.

That grant application told us something about the NIH. First, the grant application – which probably took months to write – was passed onto someone who obviously knew nothing about ME/CFS. Then that person felt perfectly comfortable rejecting the application because ME/CFS was actually depression. Whatever people at the NIH say about ME/CFS behind closed doors about ME/CFS – that’s not the message they want to send to the public.

Lastly, there was no recourse. The grant application died because one ignorant person with no knowledge – and clearly no interest in ME/CFS – blew it down. The fact that a reviewer can be so brazen about his/her prejudices speaks to deep rot that still exists in the NIH with regard to this disease.

So the NIH was always the fly in the ointment in that huge Congressional appropriation. Was it going to get serious about a condition – a post-infectious illness – that it had basically ignored for almost forty years, or would it be able to switch gears and embrace a new opportunity?

Overt Failure: Long-COVID Part I

While other research institutions were pouring money in long COVID research, the NIH ignored it.

The fact is that our worst fears – that the NIH would do to long COVID just as it had done to its sister disease, ME/CFS – and ignore it – was realized.

Two years after we knew that long COVID was a real thing, the biggest medical funder in the world has funded almost no long COVID research. The Rockefeller Foundation found that only 8 of over 200 long-COVID studies listed in clinicaltrials.com had been funded by the NIH. In a recent NIH Reporter search, I found fewer than ten studies devoted to unraveling long-COVID pathophysiology.

The reason the NIH essentially disappeared from the long-COVID funding spree that seems to have gone on elsewhere is simple: it never went to the trouble of producing a grant opportunity that would give researchers interested in long COVID assurance that the NIH would provide some funding. In fact, the NIH never even provided a Program Announcement that would alert researchers to the kind of grants it might fund. With the red flags waving that the NIH was not interested in funding long COVID, researchers didn’t bother trying.

Michael VanElzakker noted that he has “a whole neuroimaging pipeline that’s ripe for long Covid people to go through,” but is relying on charitable donations, because “there’s not really a way to apply for [NIH] Long Covid funding per se.”

Redemption or Disaster? Long COVID Pt. II – the RECOVER Initiative

Slow progress has lead to calls for reform.

But then the RECOVER initiative showed up, giving the NIH a chance to show it’s not the creaky, bureaucracy-bound institution it’s gotten so much flack for. Here was the chance for the NIH to show that it could think on its feet and respond in a timely manner to an unfolding crisis.

Director Francis Collins stated that the NIH was indeed up to the task, and it created its massive protocols within 6 months and was assigning hundreds of millions of dollars in grants in nine.

That was basically the last good news out of the Initiative. Slow progress has lead to critical assessments of the effort. In March The Rockefeller Foundation produced a damning review of Initiatives progress. It reported that:

“much of the progress so far (in long COVID) can be attributed to patient advocacy and non-NIH funded research. The return on federal investments has been poor, and knowledge about long Covid remains limited. Despite a $1 billion Congressional allocation, research into its incidence, causes, and treatments remains achingly slow.“

It recommended that the Biden Administration appoint a long-COVID point person who can corral agencies to accelerate studies already begun, launch new ones”, and concluded that long COVID should be elevated to “a national priority, and that a new task force should be created to review all long-COVID policies.

In the recent Science piece, “Glacial Pace for U.S. Long COVID Grants,” Meredith Waldman echoed the Rockefeller group’s frustration and cited the frustration of one researcher who was still waiting to hear whether his microclot grant application had been approved. Petrino bluntly accused the NIH of not making the RECOVER Initiative a priority, stating:

“Maybe they should hire people who are dedicated to accelerating these programs. [Long COVID] is a national crisis. This does not deserve to be somebody’s second or third job. What we need from the NIH right now is their full attention.”

It’s remarkable how far behind the RECOVER program is. Instead of the tens of thousands of people the NIH predicted it would have enrolled by September of this year, it’s enrolled fewer than 4,000.

In March, Health Rising asked if the NIH was going to miss long COVID; that is, if it was going to take so long to recruit patients that it was going to miss the opportunity to catch long COVID in the act during the early stages of the infection when the damage was likely done.

It noted that the NIH missed the original coronavirus, then it missed the Delta variant, and then, more than a year after it received its funding, it somehow missed the huge spike of infections associated with the Omicron variant.

Recently, a study suggested that with the Omicron variant fading, the NIH has indeed missed its best chance to catch long COVID in the act. It appears that the Omicron variant is from 25-50% less likely to produce long COVID than the Delta variant. That’s could have been predicted given the many people who have either been exposed to the virus or have already been vaccinated.

It’s also remarkable how ill-informed the effort seems in some ways. The NIH’s decision to follow more children than adults (really?) suggests it’s hardly bothered to learn about post-infectious diseases in general, and is about to waste a lot of taxpayer money to boot. The very low rates of COVID-19 in children should suggest that rates of long COVID will be low as well. The very low rates of ME/CFS in children – if anyone in the RECOVER program ever bothered to check that fact out – apparently never registered with the creators of the Initiative. It’s no surprise that the RECOVER program has enrolled a meager 98 children out of a projected 19,500.

Nine months after the NIH reported it had spent almost $500 million on long-COVID grant awards, the NIH still has not revealed the amount of the rewards for each institution, nor delineated the studies they’re funding.

The NIH, though, may have recognized it’s set itself up for a big fail. In what almost certainly set a record for brevity, the agency finally announced a funding opportunity for individual researchers in December and gave the researchers a mere three weeks to produce their grant proposals – causing some prominent researchers to bow out. .

The Gist

- With its immense budget the National Institutes of Health (NIH) is easily the biggest medical funder in the world.

- It’s slow pace, a review system that rewards established researchers who produce incremental results (instead of real breakthroughs), and its lack of creativity lead two authors recently to call it a “doddering, sclerotic” institution. Even past NIH Director Francis Collins has noted that the risk-averse climate that pervades the NIH has hampered its effectiveness.

- ME/CFS and long COVID provide two examples of how a sclerotic institution run by a good boys club has prevented the NIH from taking action on clear threats to the nation’s health. A recent application for an Abilify trial for ME/CFS that was rejected because “ME/CFS is depression” exemplifies the arrogance, lack of accountability, and ignorance that prevents diseases like ME/CFS from getting their due at the NIH.

- Similarly, the NIH’s almost total neglect of long COVID funding during the first year of the pandemic – as other research institutions were recognizing the emerging threat and funding studies to understand it – speaks again to a research institution captured by special interests (established disease groups) that see any new condition as a threat to their dominance and funding.

- Redemption was potentially in order for the NIH, though, when Congress gave it $1.15 billion to understand long COVID. Quickly building a huge program to understand a type of illness it had ignored in the past – was always going to be a stretch. The NIH, though, quickly (for it) produced the protocols and infrastructure it needed. By September of last year, it reported it would enroll tens of thousands of participants over the next year.

- Nine months later with less than 4,000 people enrolled and the NIH missing deadlines right and left, questions are being asked. The Rockefeller Foundation report called the Initiative “achingly slow” and asserted major changes are needed.

- The NIH’s decision to follow more children than adults when children rarely are affected by COVID or have ME/CFS raised basic questions about the Initiative’s thrust. Its seeming harried call for individual grant proposals that gave researchers just weeks to prepare them suggested an effort that was in flux

- The long rollout has meant that the initiative has lost its best opportunities to catch long COVID in the act; i.e. as long COVID is being produced during the early stages of infection. As the infection wanes it will be harder to find cases and the cases it does find may be less severe given that most of the population has either already been exposed to the virus or has been vaccinated against it.

- The answer to the question pf whether the NIH did to long COVID what it did to ME/CFS is yes and we’ll see. The NIH appears to have been almost unique in its ability to ignore long COVID when it first appeared. The RECOVER Initiative is another matter. The rollout has been botched but the NIH has every reason to make it a success.

- Instead of leading, though, the RECOVER Initiative finds itself far behind in the race to solve long COVID. It still, though, has immense resources to bring to bear including a highly organized and efficient effort that includes studies that can talk to each, integrated databases, sample repositories, electronic health databases, and more.

- Time will tell if the RECOVER Initiative will be the creative leader long COVID needs it to be or not.

Has the NIH Done with long COVID What it did with ME/CFS?

So the question remains: “Has the NIH done with long COVID what it did with ME/CFS over the past 35 years?” That is, basically pretend it didn’t exist?

For me, that answer is a clear yes and then probably a no. Prior to the Congressional appropriation, the NIH clearly did ignore long COVID and the massive health problem that was emerging. In fact, the NIH may have been the only major research funder NOT to take long COVID seriously. A year ago, for instance, the UK was funding more long-COVID studies than the NIH is now.

The NIH could have provided grant opportunities to study long COVID, and if it had, things would have been different. The NIH would have caught long COVID in the act, and it would have provided the kind of complex, revealing studies that it’s known for funding. If it had done that, we and the RECOVER Initiative would be a lot further along now.

The RECOVER Initiative is another story. I don’t believe the NIH ignored long COVID after it received its funding. There’s something about a billion dollars that focuses the mind – and attracts researchers. Plus the NIH was on the clock and it’s paymaster – Congress – wanted action. Efforts were being made in Congress to fund an anti-NIH – an organization called the AHRQ that could think on its feet and act creatively and decisively. How better to prove that the NIH wasn’t a “sclerotic, doddering” institution than to quickly translate Congresses money into a success?

The NIH did, in fact, seem to move quickly, but since then, something’s gone wrong. Its inability to enroll many participants, its strangely compressed grant opportunity, its many missed deadlines, and the critiques showing up in mainstream medical journals suggest that it’s really struggling.

The bottom line is that Congress gave the NIH a lot of money to figure out long COVID. The NIH always knew it was a time-limited project, that the coronavirus pandemic was never going to last forever, and that its best chance to understand long COVID was always likely receding. It could have thought ahead, hedged its bets, and found a way to quickly enroll patients, and gather their samples for future analysis in case the coronavirus pandemic petered out before it was ready to launch its massive efforts. It apparently didn’t do that.

In retrospect, instead of focusing solely on creating the massive RECOVER Initiative network of researchers, the NIH should have created a small grant program first. If they’d quickly got that program underway, they could have caught the pandemic in full force, enrolled many long-COVID patients, and produced data that would have informed its larger effort. Instead, they spent last year creating their big, integrated program – and ended up largely missing the pandemic.

Let’s not go overboard on the issues. The NIH, after all, has a billion dollars-plus to spend on long COVID. They’ve invested a lot in all the right things: making sure their studies can talk to each other, building their big data and sample repositories, etc. We really have no idea what will come out of the Initiative once it really starts rolling.

RECOVER researchers will certainly be able to study people who have already come down with cases of long COVID, and they’ll be able to catch long COVID in the act; it’ll just be more difficult, take more time and be less efficient, now. Plus, since many people’s immune systems have probably been prepared via prior infection or vaccination to face the virus, the long COVID they catch will probably be less severe. It may also be harder to find cases that persist into the long term; i.e. people who have long-term ME/CFS.

The RECOVER Initiative has started to fund individual studies and we should find out about them soon. Time will tell – and probably pretty quickly – if the NIH can get beyond its conservative, incrementalist bent and produce the kind of creative research that mysterious conditions like ME/CFS and long COVID call for. Congress primed the NIH to be the leader in the long-COVID field. With the remarkable funding it has at its disposal the NIH, in fact, must be the leader in the long COVID field. Whether it can get out of its own way and be that remains to be seen.

Sizzling! Health Rising’s Summer Donation Drive Update

Happy Health Rising piggy thanks everyone for their support.

It’s getting hotter everywhere but nowhere more so than at Health Rising during its summer donation drive. I’m behind in my figures but thanks to the over 150 people who have donated well over 13K in a week!

These kind of deep dives into what’s going on at places like the NIH aren’t the most popular posts – they don’t provide any new insights into ME/CFS, FM or long COVID or new treatment options – but since what’s happening at places like the NIH determine to a significant extent whether we will have any new insights or new treatment options, we make them a priority.

Nobody digs deeper or looks harder at what’s going on at the NIH or its RECOVER Initiative than Health Rising. If that makes sense to you, please support in a way that works for you.

Teaser alert – We have some big plans for the future that we will reveal when we get caught up. 🙂

I think what’s going on, or what isn’t going on, at the NIH is really interesting and relevant. Researchers are continually having to spend lots of time and energy on fundraising efforts and finding private donors, or attempting to get grants, instead of being able to focus on their area of expertise and study the illness.

Will Congress be checking whether the NIH has done its job properly? It’s so frustrating.

This – ” Researchers are continually having to spend lots of time and energy on fundraising efforts and finding private donors, or attempting to get grants” it appears is a common complaint. Too much time away from the bench is spending writing voluminous grants.

Very depressing.. but as you say, hopefully some good things eventually come out of RECOVER. it’s great that there’s been lots of public critique of NIH, bring on the shake-up!

Agreed – I was pleasantly surprised to find mainstream medical journals keep an eye on RECOVER:)

Something to ponder: at some point, probably sooner than later, the President will announce the nominee for NIH Director. 1) What are 5 things you want that person to know? 2) What are 5 questions you want asked in that person’s confirmation hearings?

(1) That the way the NIH is set up allows it to virtually ignore 1-2 million people with one of the most functionally disabling diseases known to man for decades.

(2) That anyone who has a health condition deserves support from the NIH. No one should have to see their illness neglected year after year after year.

(3) That several researchers who have been very successful in others fields stopped attempting to get grants from the NIH because of the bias they found was present.

(4) That the NIH has neglected for years a group of complex illnesses that a) mostly strike women, (2) rarely cause death, (3) produce enormous amounts of fatigue, pain and disability. They include ME/CFS, fibromyalgia, migraine, post-treatment Lyme disease and POTS.

(1) What is the new director going to do to ensure that diseases like these get funding commensurate with the burden they place on society?

(2) How will he/she ensure that the NIH doesn’t reward the rich (big disease groups) and neglect the poor?

(3) What kind of concrete, exciting goals will the director set for the NIH to reach.

(3) How will the director make the NIH an exciting, high-stakes kind of place where employees come to work enthused about their ability to make a difference?

Thank you. These are good. I’ll work them into some materials I’m developing.

Thanks. Looking forward to what you come up with.

The NIH a lumbering behemoth stuck in a culture of ‘the way it’s always been’. I despair when reading this along with the countless times the indomitable Dr Ron Davis has been refused NIH funding; one can only assume there is more nefarious reasoning for these rebuttals… unless of course Ron has suddenly been hit with a bout of inadequate grant writing skills.

I say circumnavigate the NIH (the organization’s disdain for anything ME/CFS related is palatable, an attitude which isn’t likely to change no matter how closely Congress is watching ), have the OMF throw every penny raised – kitchen sink included – at the nano needle development; a cheap, easy to use “definitive” blood test has to be the goal. If the NIH continue on its dogmatic path of ignoring the evidence then ignore them right back and shout to the world of philanthropy ” we need help!”

With weight of evidence a benevolent donor will appear.

Did you see Avindh Naths latest video on long Covid, which shows how they’re framing this and also Ongoing absence IMO of any regard to the ME community? If the NIH mecfs study has shown anything revelatory (other than perhaps informing their long covid hypothesis) he didn’t indicate this. He instead presented MECFS , GWS & Chronic Lyme (which if added together probably are disabling 0.5% of the working age population) as diseases that had been there for decades, that no scientists knew how to study (yes he said that) & that the long covid research being done might possibly address too, (imo most likely if, like long Covid, people are still in the earlier stages because he is talking about blocking the immune response that we know can spiral, not about reversing the damage that will be there in ME). That’s the extent, seemingly, of his mecfs care & ambition.

So disappointing…it sounds like the CDC is about as nimble as government and the RMV ! Why am I surprised ?

Cort you have mentioned the UK and approach to Long Covid in our hospitals since the start of the pandemic. I would really like to highlight the ‘UK Phyto-V study’ results which were released in April this year. They received a lot of attention here on TV networks at the end of April, but I don’t know how much international coverage was given. It was a nutritional study run by “consultants and scientists from Bedfordshire and Adenbrooke’s Cambridge University Hospitals”. I don’t have Long Covid but have suffered with ME/CFS for too long. We have to do the research of what’s out there ourselves and to decide which supplements to take to try to improve this awful disease we are suffering from. If anyone is suffering from Long Covid or even ME/CFS please take a look at the study based on nutritional supplements on the following website.

Phyto-V.com

I decided to start taking them 6 weeks ago and they seem to be helping me with upper abdominal health issues. I am hoping that they will continue to be of benefit in the long term and I am prepared to give it a long personal trial.

I can’t make any claims or recommendations but please read the trial information and testimonials from people who have been on the trial, who have been suffering from Long Covid.

I hope this is OK for me to post this Cort? Just trying to put possibly good details out there for people. Thanks for the wonderful work you are doing on our behalf.

Of course it’s OK to post here – this is exactly the kind of comments we want! Thanks for passing that on. I look forward to checking it out.

https://bmas.blog/2022/04/11/the-uk-phyto-v-study/

I’m also in the UK. I have longterm severe ME. I have not had Covid, but I did have very bad reactions to my Covid vaccines – still not over them.

The ONS (Office of National Statistics) started testing volunteers (chosen at random) for Covid each month when PCR tests first became available about 2 years ago. They have also taken pin prick blood samples from some people to test for antibodies for Covid.

I started getting monthly visits from the ONS last summer to do a PCR test each month and I’m asked lots of questions – things like do I have any of a list of certain symptoms, what contact I’ve had with other people, where I’ve been, what date I had vaccines etc. It said I was selected at random. Oxford University is working with the NHS to do the research, headed by the lady who created the Astra Vaccine. Over the months the questions now include things about Long Covid too. Participants have been asked if the researchers can look at participants medical records for the next 15 years and from 4 years prior to the pandemic starting, to help them try to understand why people have been affected so differently by Covid. Also to see if those who have had Covid need more hospital and doctors appointments over the years to come, compared to those who haven’t had Covid. They originally asked if they could keep any blood samples taken, but have recently asked if they can extend the time that they can keep any test samples taken from participants. Although they have scaled down the testing it is still continuing – I had my latest test today.

Very impressive! I’m sure the RECOVER program will get there!

Cynic here.

Releasing who and where the initial portion of 1 Billion was spent may INFORM who might have received a heads up prior to the announcement of a three week window to submit NIH grant applications for long Covid.

Again, is anyone suing, NOT the NIH now, but CONGRESS over ‘their’ NIH’s declining an application based on the NIH’s reviewer FAULTY to the point of criminal, definition of ME/CFS.

And yes, we want Congress support, and it may be that Congress needs a reason ( being sued) to take charge of the ‘NIH’ situation.

Lots of problems – and that 3-week window – wow! They did show some urgency, that’s for sure.

I’m with you, Sunie. Our government is so corrupt right now, how do we know where this money has even gone? To what extent are we reaching the right people? I’m fed up with medical care. I now live in a rural area and have ZERO help for my ME/CFS. I can barely walk anymore, so some rich friends gifted me an electric WC. The pain is only bearable because I have taught myself to “grip it” in my mind. And no doctor. Our government is an antiquated mess. Sorry, but I am more than cynical. I see “human advertisements” for votes, wealth, and status in government, and not a lot of people doing their jobs. So what we want out of Congress and need out of the NIH may be a long shot.

Surely there must be something we can do about this? Though I’m not American. How about a joint effort with the other low ratio funding diseases to get equitable funding.