A longtime cancer fatigue researcher finds the same microglial cell abnormalities in long COVID.

Glial Cells to the Fore Again

Could the “brain fog” in long COVID, ME/CFS, cancer fatigue, and similar conditions be caused by the same process?

Chemo fog, brain fog, fibro fog – even “COVID fog” – it’s a foggy world out there for people with cancer-related fatigue (chemo fog), brain fog (ME/CFS), fibromyalgia (fibro-fog) and COVID-fog (long COVID). Terms like this don’t spring up out of anywhere – all these conditions are characterized by cognitive problems, fatigue, and exertion problems.

The fog isn’t only in the patients’ brains. Despite the fact that the symptoms of cancer fatigue or chemo-brain are very similar to ME/CFS, and that cancer fatigue has been recognized for a couple of decades, few studies have assessed the two together. Unbeknownst to most of us, though, cancer fatigue and chemo-brain studies have been focusing on a familiar topic in ME/CFS – the microglial cells and neuroinflammation – to explain it.

In 2018, a Stanford neuro-oncologist and MacArthur “genius” grant recipient, Michelle Monje, who has been studying microglial activity for over 20 years, created a chemo-brain mouse model which found that chemotherapy resulted in microglial and astrocyte activation and cognitive problems. The study an unusual long-term depletion of specialized cells called oligodendrocyte progenitor cells (OPC) which produce the myelin sheath that protects the nerves and aids in signal transmission.

Similar findings are present in multiple sclerosis. In fact, the authors reported that the OPC problems “remain a pressing question” in cancer-related fatigue, multiple sclerosis, and neuroinflammatory diseases.

A couple of years later, a pandemic producing very similar phenomena called “covid-fog” or brain-fog piqued Monje’s interest. Just as the ME/CFS community did, Monje told Stat News that she suspected a syndrome similar to cancer fatigue was about to show up.

“I worried back in the spring of 2020 that we would perhaps see a syndrome very similar to what we see after cancer therapy, that we might start to see a cognitive syndrome characterized by things like impairment in memory, executive function, attention, speed of information processing, multitasking. And then, you know, within months, reports of exactly that sort of complaint started to emerge.”

She was most interested in the same type of COVID-19 patients that the ME/CFS field is interested in: people with mild COVID-19 infections who come down with long COVID.

The Study

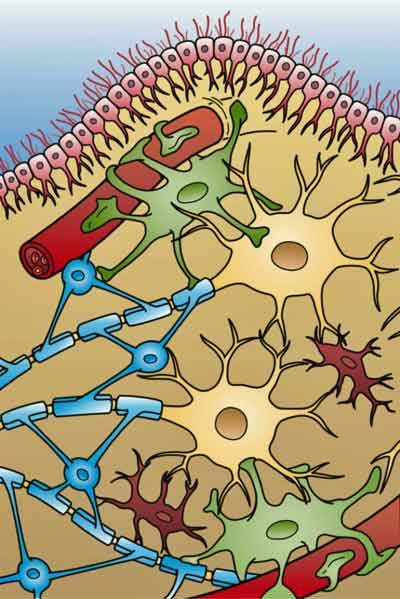

Glial cells are a focus of interest in all ME/CFS-like diseases. The four different types of glial cells found in the brain (: Ependymal cells (light pink), Astrocytes (green), Microglial cells (red), and Oligodendrocytes. (light blue). (From Holly Fisher – Wikimedia Commons.)

Taken together, the findings presented here illustrate striking similarities between neuropathophysiology after cancer therapy and after SARS-CoV-2 infection, and elucidate cellular deficits that may contribute to lasting neurological symptoms following even mild SARS-CoV-2 infection. Fernández-Castañeda and Monje et. al.

Monje’s recent preprint, “Mild respiratory SARS-CoV-2 infection can cause multi-lineage cellular dysregulation and myelin loss in the brain,” (which includes Avindra Nath as one of many co-authors) indicated that a COVID-19 mouse model, plus autopsy results, and bloodwork from long COVID patients, revealed an eerily similar phenomenon to what was found in her chemo-brain study.

As the title indicated, it didn’t take much of a coronavirus infection at all – just a mild respiratory infection – to potentially produce “a profound multi-cellular dysregulation in the brain”. There was activation of the microglial cells associated with myelin sheathing covering the axons of the nerve cells – the long “wires” that connect one nerve cell to the other. Since myelin plays an important role in the transmission of nerve signals, even a small loss of myelin could impact cognitive functioning. Plus, the microglial activation could induce the astrocytes to kill neurons.

The Gist

- Michelle Monje, a Stanford neuro-oncologist, had been studying glial cell functioning in cancer-fatigue – an ME/CFS-like condition – when the coronavirus pandemic showed up.

- Despite the fact that she was studying a condition not caused by an infection – she immediately suspected that similar cognitive and other symptoms to cancer fatigue would show up in long COVID – and so they did.

- Her cancer fatigue mouse studies lead her to suspect that glial cell activation triggered by chemotherapy was interfering with the myelination of the axons that connect one neuron to another. The myelin found on the surface of these nervous system “wires” helps speed signals between neurons.

- Both a long COVID mouse model (yes, they apparently already have one) and an autopsy and bloodwork study suggested that a similar process was occurring in long COVID. Similar bloodwork findings have shown up in ME/CFS and long COVID.

- Monje cautioned about quick results but stated that treatment trials (probably in animal models) are beginning.

- Several studies in both ME/CFS and fibromyalgia point a finger at the glial cells and neuroinflammation and demyelination in ME/CFS.

- With similar brain findings showing up in long COVID, cancer-fatigue, ME/CFS, and FM the prospect that core processes in each condition would be targeted with the same treatment presents itself. As Nath emphasized “the humongous” overlap between these seemingly different fields and how much each has to teach the other. Ultimately, they should all be able to benefit each other.

She noted that even mild SARS-Cov-2 infection can induce prominent elevations in CCL11, a chemokine that’s been associated with “brain fog”. Increased levels CCL11 levels, encouragingly, have shown up in spades in ME/CFS including one study in which they were correlated with worsened cognition (and increased pain.) and a cerebrospinal study that proposed they reflected immune activation of the central nervous system. Higher CC11 levels have also been found in fibromyalgia, in people experiencing neuropathic pain, and in other long COVID studies.

Of course, the coronavirus is only the most prominent agent of cognitive impairment that we’re dealing with. Monje pointed out that other triggers – such as bacterial toxins, people who experience post-intensive care syndrome (PICU), and who come down with influenza – can also show declines in cognitive functioning.

Next Steps for Treatment

Monje et al. ended by reporting that “microglial depletion strategies”, and anti-inflammatory and neuro-regenerative strategies – most being assessed now in animal studies – have been shown to “rescue cognition.” CSF1R inhibitors, such as PLX5622, and similar agents that are currently in clinical trials can “restore similar multi-cellular deficits and rescue cognitive performance” in mouse models. The authors called these approaches “promising therapeutic avenue(s) to ameliorate the chemofog found in cancer fatigue”.

Beth Stevens, a Harvard Medical School professor, who discovered that the microglial cells in the brain were the brain’s main immune cells – a rather important finding – told Stat News that “clear next steps” regarding testing therapies for long COVID exist”. That doesn’t mean drugs would be available tomorrow but that the often arduous process of testing should begin now.

Monje was being prudent: “I don’t want to speculate about what therapies might be useful because I can’t recommend anything we haven’t tested. ” However, she stated that testing is beginning: “We will be testing potential interventions first in preclinical models and then there will be carefully controlled clinical trials so that we can identify the best and safest. But I wouldn’t want people to think, ‘Oh, I read somewhere that x y z, you know, calms down microglia.’ I’ve seen that happen on Twitter.”

ME/CFS and Fibromyalgia Connection?

Unfortunately, not a word was mentioned about glial cells in the big post-infectious disease (ME/CFS) or fibromyalgia. It’s certainly not for lack of interest in either disease. From Jarred Younger’s ME/CFS thermography study and his longstanding interest in glial cells and neuroinflammation, to Herbert Renz-Polster’s recent “The Case for Neuroglial Failure” hypothesis for ME/CFS, to the fascinating fibromyalgia study which found that antibodies from FM patients had wrapped themselves around the glial cells in the dorsal root ganglia, plenty of data is also pointing to the glial cells in these diseases.

Plus, Barnden’s brainstem ME/CFS studies point to demyelination in that crucial regulator of breathing, heart rate, sleeping, immune regulation, sensory processing, etc. Barnden came to the demyelination idea via evidence of increased myelination in the nerve axons going from the brainstem to the premotor, primary motor, primary somatosensory cortex, and prefrontal cortex.

Since myelin enhances signal transmission, Barnden believes the increased myelination he’s seen in ME/CFS (which has also shown up in other diseases) is an attempt to compensate for balky signals emanating from a demyelinated brainstem. These areas, interestingly enough, regulate movement, encode sensory information (heat, cold, touch), produce executive functioning, and regulate limbic system activity – all areas of concern in ME/CFS. Given that, it’s perhaps no surprise that brainstem problems have already shown up in long COVID.

All Together Now?

While Monje didn’t make the connection between ME/CFS and long COVID and cancer fatigue in her long- COVID paper, the Washington Post, in an impressive article, “How covid brain fog may overlap with ‘chemo brain’ and Alzheimer’s“, did.

The article cited Avindra Nath, who’s taken seemingly every opportunity to plug the connection between long COVID, ME/CFS, and other post-infectious conditions. Nath stated, “There is humongous overlap” between long covid and these other conditions.”, and that, “We as a research community are very interested to see how whatever knowledge we have about other diseases can make a difference with long covid”. Let’s hope!

(Nath – one of the few researchers who had any interest in post-infectious illnesses prior to the coronavirus pandemic – has, by the way, actually been tracking symptoms in 200 Ebola patients and 400 HIV patients for years.)

The more different eyes, the more that researchers from long COVID, ME/CFS, GWI, cancer fatigue, Post-ICU illness, etc., fields collaborate and learn each other’s work, obviously the better off each field is. In that vein, the entrance of another ME/CFS/FM-related field – cancer fatigue – into the long-COVID fray is potentially a very good sign.

Dr. Lekshmi Santhosh – the founder and medical director of U.C.S.F.‘s Long Covid and Post-I.C.U. Clinic – noted how important that all these fields be studied on a recent Ezra Klein podcast. She emphasized the strong overlap between long COVID and ME/CFS as well as post-intensive care syndrome – which has been featured in several Health Rising blogs.

Even Alzheimer’s researchers may get in the act, as some long-COVID researchers have found – to the researchers’ surprise – increased high levels of the phosphorylated tau proteins that are typically found in Alzheimer’s. The proteins were not found in the higher learning centers of the brain – as occurs in Alzheimer’s – but, interestingly enough, in the parts of the brain that control movement. We don’t think of GWI or ME/CFS in the same vein as diseases like Alzheimer’s, but recently, high levels of antibodies to the phosphorylated tau proteins – were found in Gulf War Illness, and the 2005 Baraniuk brain proteome study suggested increased levels of amyloidic proteins were present in ME/CFS patients’ brains.

Considerable heterogeneity, of course, exists in all these diseases. Long COVID, apparently, is every bit as variable as ME/CFS is (“If you’ve seen one long-COVID patient you’ve seen one long-COVID patient”; i.e. the next may be very different). We’ve long wondered, of course, about how many subsets exist in ME/CFS.

It would seem to make sense that these diseases would be dramatically different. Long COVID, is, after all, triggered by the coronavirus virus; ME/CFS by viruses, bacteria, fungi, toxins, and probably other things; post-Lyme disease by tick-borne bacteria; post-intensive care syndrome by being in the ICU; cancer fatigue by chemotherapy; and Gulf War Illness by toxin exposure. These are all very different triggers, yet these different triggers still manage to produce quite similar symptom patterns.

The latest cancer-fatigue research suggests that deep in the brain, similar processes may be going on. That would be a great win for all of these diseases, as core problems would provide core targets for treatments – potentially speeding up the process of finding treatments greatly. In that vein, it’s interesting that Nancy Klimas’s modeling work suggests that the same treatment (etanercept/mifepristone) protocol should work in two diseases with very different triggers (Gulf War Illness/ME/CFS) and quite different immune signatures. May that pattern continue!

Thanks again Cort! I’m hoping these approaches merge into something really useful. Are there any updates on Dr. Klimas’ trials yet?

I’m looking forward to watching the recent video from her conference and finding out.

Once again the dorsal horn and dorsal root ganglion rears it’s head (pun intended). The fact that encephalitis and meningitis, ME/CFS, craniocervical instability related ME/CFS and FM, and various forms of Fibromyalgia (Chiari Malformation, post whiplash induced FM, etc.) all include some kind of damage and/or dysfunction in the dorsal horn, resulting in hyperalgesic pain syndromes, is significant.

Considering that other types of FM include mechanical damage to the dorsal horn, I have always wondered how the damage and/or dysfunction occurs in post-viral illnesses like ME/CFS (I strongly suspect that the CNS swelling in encephalitis and meningitis causes ischemia in the dorsal horn, resulting in hyperalgesic pain similar to ME/CFS and FM); is it purely ischemic, or is there an immunological component as this article alludes to?

I find it interesting that polio doesn’t directly attack the anterior horn and the damage to the motor cortex is actually secondary to ischemia within the anterior horn. My hypothesis regarding damage to the dorsal horn is that a similar ischemia is the cause; but an immunological component makes sense too. Of course we have to be careful to rule out the possibility that those immunological effects on the dorsal horn aren’t just a reaction to the damage as well and might not be causative.

Fascinating stuff! Thanks for the report Cort. 👍🏻

Thanks again, Cort. Such encouraging news! Both the research findings, and the researchers relating across diseases. So good to see.

Here’s also an excellent video by Dr. Monje, with clear explanations of her work.

https://m.youtube.com/watch?v=szyHCvtsJ_c

I wonder if these processes that cause brain fog also impair vision? My vision is always blurry when my cognitive function is struggling.

Low blood glucose can cause blurry vision.

The first symptoms of low BG tend to be cognitive: difficulty with word recall and simple maths problems. Sound familiar?

Have you tracked your blood glucose at home through out the day, and when you are crashed, having symptoms, etc?

Great article, as usual.

I do NOT want to get into a political discussion, but mifepristone is now going to be hard to come by, if not impossible, for research and treatment.

The results of that trial are be so interesting. Dr. Klimas certainly seemed to indicate that it really had potential for these diseases. I wonder if she knows what the results are….

I have been thinking of similarities for a long time. There are alot of them. Thereby I think we can “copy” many ways of managing symtoms etc. One thing the community argue about is this about excercize. In all other diseases excercize is good, but not in ME. Is said. But I think it even is good for ME, the excercize/activity you c a n do. Without getting worse. And that also is similar to all other diseases, it’s just that in ME, you can often do much, much, much less. So much less that doctors prescribe tooo much, even if they think it they almost precribe “rest”. What I want to say by this, yes we have to describe the severity and the PEM issues, but we must also look at similarities so that we can benifit from already known coping strategies from other diseases. Which your text absolutely promote (I do not know if promote is the right word, but .. well).

So interesting! Oligodendrocyte precursor cells and oligodendrocytes contribute to axonal insulation but are also involved in extracellular glutamate homeostasis and thus play a role in the regulation of excitotoxicity – clearly an issue in #MECFS. Here the findings of abnormal Eph-ephrin signalling from Maureen Hanson´s lab (https://www.mdpi.com/2227-7382/9/1/6) may fit into the picture as this pathway is involved in regulating oligodendrocyte and oligocyte precursor functioning (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4568937/). Also, Eph receptors are highly expressed in brain regions with morphological and physiological plasticity, like the amygdala and hippocampus – which are of particular interest in ME/CFS research.

Thank you for this nice summary!

Hi, Dr. Renz-Polster. After reading your “The Case for Neuroglial Failure” paper, I had a question regarding a strange symptom I experience and if you believed that it could be potentially caused by glial cell activation. I sent you a DM on Instagram if you’re able to see that.

What a comprehensive write-up. Thank you, Cort.

Thanks! I really like it when the fields start to come together – its inspiring to me. 🙂

swell.

From Wikipedia: ‘A diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma (DIPG) is a tumour located in the pons (middle) of the brain stem.’ This is and has been Dr. Monje’s principal interest for a number of years. She is a remarkably accomplished person.

My hope is that she’s a great multitasker too, and is able to dedicate a few members of her team to work steadily on connecting the loose ends of these related conditions.

Our planet is blessed to have her.

NIce to hear she’s so focused on the brain stem! Not many researchers are. VanElzakker pointed out some time ago that most brain scans can’t really access it very well. It sure presents some possibilities for ME/CFS/FM and long COVID.

This feels tangible because of the overlap with other conditions. Thanks Cort!

Agreed! The more overlap the better. 🙂