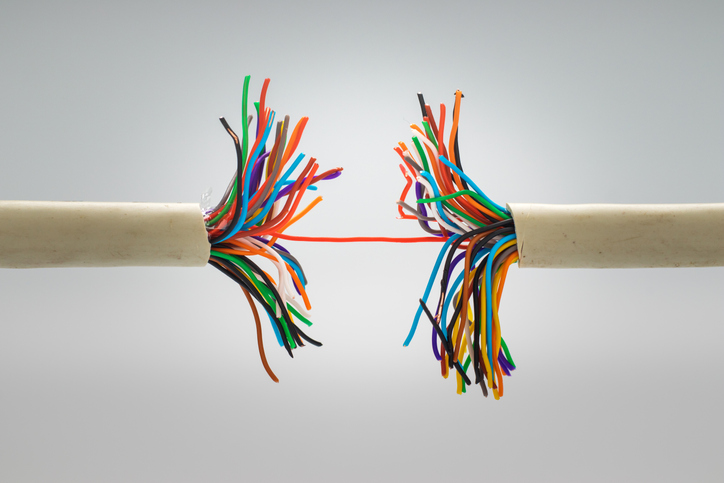

Yes, there is a gut-muscle connection! Could it be broken in ME/CFS and allied diseases?

We’ve all heard about the gut-brain axis. That’s where problems in the gut can translate to inflammation in the brain and vice versa but a gut-muscle connection? That’s entirely new. One wonders much further can the gut after all reach? It turns out quite a bit further than we thought. Like so many fascinating discoveries, it took a bit of serendipity to uncover this one. (Thanks to Neilly for the tip.)

The Gist

- We’ve all heard of the gut-brain connection where inflammation in the gut can cause inflammation of the brain and vice versa but a gut-muscle connection? That’s something entirely new.

- It showed up when, to their surprise, Harvard researchers found gut-derived immune cells called T regulatory cells or Tregs in the muscle tissues of mice. Tregs regulate the functioning of the immune system; in particular, they’re the cells that swoop in and turn off the immune response when it’s time to do so. Regarding the gut, they’re the main immune cells involved in the gut’s regulation of the immune system. They’re a big deal.

- It turns out that exercise produces inflammation and produces small amounts of damage to the myofibrils found in muscle cells. This is usually quickly and easily resolved in healthy people…but what about exercise-challenged ME/CFS, long-COVID, etc. patients?

- The late Ron Tompkins proposed that exercise was damaging the myofibrils in ME/CFS patients, and several studies suggest that damage is indeed being done.

- Exercise, for instance, produced higher-than-usual amounts of inflammation in ME/CFS. It also appears to produce higher-than-normal rates of bacterial leakage from the gut (another source of inflammation). Reduced levels of protective substances (heat shock proteins) could be leading to more muscle damage.

- Finally, Maureen Hanson’s NIH-funded research groups recently found that exercise is not provoking nearly as much of a metabolite or protein response as expected, i.e. the “healthy metabolic response” to exercise, in other words, had disappeared.

- But what about those gut Tregs? Although they’ve never been studied in ME/CFS, some indirect evidence suggests they could be affected. Tregs, it turns out, are produced by the same factors – small chain fatty acids such as butyrate – that gut studies indicate are low in ME/CFS. It’s possible, then, that butyrate depletion in ME/CFS patients’ guts results in low levels of Tregs – too low to turn off the already very vigorous inflammatory event we know that exercise is producing.

- Could problems in the gut have kicked off ME/CFS? Lenny Jason’s studies of college students who came down with infectious mononucleosis suggests so. People who later developed a more severe form of ME/CFS experienced more gut symptoms when they were healthy – and get this – people who had IBS prior to coming down with infectious mononucleosis had an 80% chance of coming down with ME/CFS later on.

- Maybe the alternative health practitioners who have been saying for years that it all starts in the gut were right.

It turns out that gut Tregs play an absolutely essential role in the gut’s effect on the immune system. A recent study reported that, “Although the mechanisms are still unclear, the immunomodulatory effects of gut microbiota are mostly realized through the Th17/Treg axis”. Poor Treg functioning could result in inflammation in the gut, and if leaky gut is present – and we know it is in ME/CFS – outside it.

The Harvard researchers proceeded to validate their findings. Mice that had been genetically modified to lack this special class of Tregs had more trouble recovering from exercise, exhibited higher levels of inflammation, more muscle injury, and developed muscle scarring. It was clear that without the Tregs there to snuff out the inflammation, the muscle repair mechanisms simply weren’t up to the job.

Going to the nuclear option and knocking out the mice’s entire gut flora provided the same result – making it clear that the gut flora did indeed play a role in exercise recovery. Digging deeper, the researchers found that these colon-derived Tregs enhance the muscle repair process by suppressing an immune factor called IL-17. In, “How gut microbes help mend damaged muscles”, Bola Hanna, the lead author of the study, told Ilima Loomis:

“When muscles are healing, you need a certain dose of inflammation within a certain time frame… in the absence of these gut-derived regulatory T cells, we found that the degree of inflammation gets higher and extends for longer, and you end up having inferior repair.”

Muscle Repair Problems in ME/CFS?

What about ME/CFS? We know plenty of gut problems exist in ME/CFS but what about muscle repair? Is that damaged? Could gut-associated Tregs be failing to calm the fires, so to speak, in the muscles after exercise in ME/CFS? Other than a hypothesis that Tregs are failing to reign in herpesvirus infections, we have little information on the role they play in ME/CFS.

The late Ron Tompkins proposed, though, that exercise may doing lasting damage to the small myofibrils which make up our muscle fibers. Stress to the muscles from exercise does, in fact, damage those myofibrils even in healthy people, but the damage is quickly resolved, and Tompkins believed that the muscle repair processes may be broken in ME/CFS.

Indeed, studies that have found that exercise invokes higher than usual amounts of inflammation in ME/CFS would clearly put a premium on the muscle repair process. Shukla, for instance, found high rates of bacterial leakage into the bloodstream (aka inflammation) which were still present 72 hours after an exercise bout. In several small studies, Jammes found high levels of oxidative stress and reduced levels of protective factors after exercise. In a review article, he proposed that high levels of oxidative stress may be preventing muscle cells from responding properly to exertion in ME/CFS.

Maureen Hanson’s NIH-funded research group recently suggests that little is going right in people with ME/CFS after exercise. While the healthy controls showed a veritable explosion of metabolite alterations, the metabolites in the ME/CFS group basically flatlined. The “healthy metabolic response” to exercise, in other words, had disappeared. A proteomic study from her group found much the same thing – a much subdued proteomic response to exercise – in ME/CFS. Men, in particular, appeared to show dramatic changes in gene expression during the muscle repair period that occurs after exercise.

While it won’t tell us anything about Tregs, the OMF’s fascinating skeletal muscle study underway at the Harvard Collaborative ME/CFS Center should give us a ground-level view of what’s going on in the muscles. The unique study methodology involves using muscle biopsies to compare the expression between younger and older people undergoing 2 weeks of bedrest and then rehabilitation – with those of ME/CFS patients. Thus far, the study has found that 2 weeks of bedrest produces profound differences in gene expression. Ultimately, the study should be able to show that deconditioning produces a different impact on the muscles than seen in ME/CFS.

Back to Butyrate

Back to these gut-derived Tregs. We don’t know if missing gut Tregs are causing a problem in ME/CFS or not – so far the muscle-gut finding has only been explored in mice – but some other factors suggest they just might be. It turns out the Treg production in the gut needs the very substances – short-chain fatty acids (butyrate, propionate, and acetate) – that recent studies indicate are lacking in ME/CFS patients’ guts.

It should be noted that low butyrate levels are not just a problem in ME/CFS. The fact that butyrate and short-chain fatty acid problems are found in a host of other diseases (Alzheimer’s disease, multiple sclerosis, Parkinson’s disease, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, stress, anxiety, depression, autism, vascular dementia, schizophrenia, stroke, diabetes, lupus, myasthenia gravis) makes one wonder if the gut dysregulation really could be the source of many diseases.

Indeed, Lenny Jason’s study that tracked college students after they came down with infectious mononucleosis found that people who later developed a more severe form of ME/CFS – the kind that most of the people reading this blog probably have – experienced more gut symptoms when they were healthy.

People who had irritable bowel symptoms (bloating, pain, etc.) when healthy, and severe gastrointestinal symptoms when they came down with mononucleosis (and low levels of IL-13 and/or IL-5 at baseline), had nearly an 80% chance of developing severe ME/CFS six months later.

Functional and alternative health doctors have been saying for years – it all starts in the gut… They may be right.

Thanks for this, Cort. I’ve been in physical therapy for my shoulder once a week for the past month or so, and every time I crash for a few days after. I’m about ready to throw in the towel. What’s odd is that even though they have me doing resistance exercises, I never feel muscle soreness in the days after. Just pain in the joint and a flare of my fatigue and neuropathy. It’s almost like my muscles aren’t having a lactic acid buildup after being taxed. Very odd. But seems to be in line with these findings.

I’m also totally convinced this is all stemming from my gut. I have had chronic constipation since getting COVID in March 2020, and I’ve tried so many different things to resolve it, to no avail.

Amy, I totally understand your predicament. I’m about ready to throw in the towel too. I have a physical therapy appointment scheduled this afternoon and I’m all stressed about it because I’m dealing with a flare up. I’ll just need to tell the therapist I can’t do the exercises. Basically, I’ll just lie on his table and hope the therapist can help.

Cort, thanks again for an informative recap of the study. My Gut issues typically surface after exertion (of pretty much any kind).

Now for a treatment that work better than kimchee or whatever.

Hi Amy,

In case it’s of help— I too have had periods of constipation esp. after viruses. What has unexpectedly turned out to resolve it for me is regular use of *organic ground flaxseed*. I get it inexpensively at Trader Joe’s. I tried it on a whim, just as as a healthy add-in to yogurt— bit then noticed the unexpected help in “regularity”. How great if it worked for you too!

Amy, muscular soreness stems from micro-tear of the muscle fiber, not from metabolic buildup. Your resistance training probably isn’t hard enough to cause it, but still strong enough to cause minute inflammation spike that last several days. Just about any exercise that MECFS patients can muster is.

Just a suggestion, Cort. And everyone else. http://www.hugorodier.com. He is a very interesting physician whose quest is microbiome correction. “48 minute health lesson”, a video on his website, is integrative and informative. He does a “gut mapping” test. The results are fascinating to me (as a clinician, a PA, before becoming ill.)

He has already helped me. His nutritional treatment means being willing to temporarily do without some of the only simple pleasures we have left. Lots of green smoothies (they really aren’t bad.)

Thanks for the link 🙂 Gut mapping sounds interesting!

Diagnostic Solutions Laboratory, Alpharetta, Ga. GI-MAP, GI Microbial Assay Plus

Thanks for info about Dr. Rodier. Was unable to find the particular video you are referring to. What is the full title? Also what tests did you need to do? Lots of ME/CFS pts have done raw food, and juicing this it came out of their ears and the ME did not abate. How did his treatment help? Really need help for a family member. Thanks

If you scroll down on Dr Rodier’s home page there are several links in red letters. “48 minute Health Class” is the specific one to which I was referring, buy they are all good. I listed the name of the lab that did my GI mapping test, above in a post from yesterday. There isn’t juicing involved. I guess the trick is, when the ordering clinician gets the results of thes test, he or she needs to know what to do to correct the microbial imbalances. And that is tricky. But he, Dr R, has been studying it for years and he knows how to correct imbalances. He does phone appointments.

Hi Cort, do you maybe know in the OMF’s study, i Thought around a 100 biopties in healthy ones but with how many ME/cfs patients they will compare? and wich criteria? IOM, CCC, ..?

Also the butyrate, if it excists, taking it, would it help? Or is it only 1 piece of a verry complex puzle. to ill to reread the NIH study’s on gut.

They usually use CCC. I don’t know the breakdown – they have quite a few groups in there! Butyrate pills do exist and they apparently can be helpful. Also fermented foods if you can handle them, prebiotics, non-digestible starches, some probiotics, andrographilide…

https://www.healthrising.org/blog/2021/11/24/butyrate-chronic-fatigue-syndrome-long-covid-bacteria/

The problem with some of these studies is that they compare MECFS patients, who are often severely deconditioned, with healthy controls. I learned how deconditioned I was when I first attempted get back on the ski slope, despite light exercises I’ve been doing regularly and the 6-month long road trips I made a few months before. I was cramping all over just trying to walk up to the ticket booth while carrying the skis.

The study that showed that MECFS patients had more inflammation after exercise, for example, appears to have used healthy controls. Deconditioned people will end up with more muscular/cellular damage from an exercise and therefore more inflammation. So, we don’t know if the excess inflammation was because of MECFS or deconditioning.

Yes, I haven’t checked the studies but in general that’s true and that’s why the OMF study is using deconditioned healthy controls.

We should be clear, though, that not everyone people with ME/CFS is deconditioned. I’m not deconditioned for instance. I may not be in good shape but I’m not deconditioned and my average steps per day are probably pretty average. The people with ME/CFS who get into these studies are probably healthier than most people with ME/CFS. However, we don’t know their physical condition.

Ideally, I suppose you would use actimeters or whatever they are to assess steps and calorie usage in the different groups. That would help a lot and potentially remove some worries about deconditioning (or increase them! :))

I think the most important thing is that these studies don’t include fit controls – that’s a recipe for potential disaster. Hanson’s two recent studies – both mentioned in this blog – used healthy controls who did not engage in physical exercise in one and in sedentary healthy controls.

Hopefully, that’s good enough – you can only go so far!

Ah, OK. Maybe they used deconditioned healthy control. I clicked the link and the text simply said “healthy control”, so I assumed average healthy people. And, yeah, patients in the mild end of spectrum may not deconditioned. People in general go out of conditioning very quickly though. All it takes is a PEM; you get deconditioned by the time you are out of PEM and have to start all over again. It’s a Sisyphean effort for those who falls into PEM regularly.

Very interesting!

Tregs also influence allergies.

Potentially low Tregs in the gut could be causing / contributing towards plenty of ME/CFS symptoms, including PEM, allergies, IBS….

Certainly an interesting hypothesis!

Interesting paper on dietary factors and TRegs:

https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fnut.2022.878382/full

Cort, I am curious. What are your main symptoms of ME/CFS? You said you are not deconditioned and can walk the expected number of steps per day for your age. It is obvious that you don’t have brain fog since you can read and write an lay interpretation and (even more difficult) the gist of fairly dense scientific studies.

I was originally diagnosed with ME/CFS and focused on that for a long time but I think I have a more fibromyalgia-like presentation – lots of burning muscle pain and other types of pain – particularly after exercise, inability to do any kind of strenuous exercise, (I probably walk too much – I do so for the dogs and that is the absolute limit), poor sleep, a tremendous amount of fatigue, and yes, brain fog believe it or not, a huge difficulty getting my body/mind to settle down, a big problem with chemical sensitivities, some IBS….

Thanks, Cort. I appreciate your sharing your experience.

Cort, your clinical presentation sounds much like mine except I have some orthostatic intolerance and elevated methylhistamine. I have gone back and forth with the ME vs CFS question, but they have really become one in my mind now. The findings of OI, mitochondrial problems, viral and toxin triggers for FMS, gut issues, SFN also, have made FMS a bigger picture for me. Because of extensive testing for several years, including the mass spectometry epigenetic IGL Neuroscan from Germany, I am a poster child for all the markers that get mentioned for both syndromes. But I cannot exercise the way some FMS patients can.

I have been clueless at what has triggered so much burning pain, as I do have lactic acid buildup on my organic acids tests and huge waste buildup from uncleared cell death, impaired energy production, etc. I remember thinking some years back, why doesn’t exercise make me feel good anymore.

Well we have the answer with the NIH study on exercise metabolites. No reward from the body. Also thinking, what happened to pleasure, effective pain relief from meds, well we have the answer with the alterations in opioid receptors and the tapped out already on endogenous opioid system. I imagine you have a lot of fatigue from mental effort for sure. Thank you for that sacrifice.

I have also recently been given the CIRS diagnosis and have the HLA DR gene for not clearing from the innate to adaptive immune system and my GENIE sensitivity genes are off the charts though the GENIE doesn’t show CIRS per se. But Dr. Heyman will be the first to say that all of this including Long Covid are really the same reaction by the body.

I keep going back to Naviaux. We can chase this thing downstream forever, but a genetically programmed response to a biological hit of many types takes us out of commission to varying degrees. It just makes sense. I have had the switch turn off two times for short periods, only hours, last time in 2021. It was amazing to be me again. But then it flips, it’s something so strong it overrides medications that do work and suddenly stop, recoveries that are suddenly over. It’s primordial I believe, and we need to find the genetic switch.

Forgot to mention, the most upregulated gene on my GENIE test was for PTSD. The trauma connection.

Very interesting, Cynthia. My PTSD was turned on as well on my first GENIE. After moving to a new home and retesting a little less than one year later my PTSD genes turned off. Bad news is I continued staying in a sterile environment and my PTSD turned back on again with another repeat GENIE.

What have I learned from GENIE? Can’t say. Only that genes inappropriately turn on and off at various points of time for whatever reason.

Thank you for sharing your knowledge. I like what you have to say in your comments and tend to share most of your beliefs/thoughts.

In the many, many years I have had ME/CFS, I would best describe my overall day-to-day health as a feeling of being chronically poisoned.

In the past six months, this has segued into four episodes of right kidney pain and violent vomiting for a day. A C-T scan revealed nothing remarkable like a kidney stone. Some bacteria were found, but nothing to indicate a roaring kidney infection although each doctor prescribed an antibiotic.

This morning, I thought that the chronic poisoned feeling might be from a kidney disorder so I did some research and found this remarkable diagnosis and treatment on ME Action’s treatment page.

https://me-pedia.org/wiki/Dr_Markov%27s_chronic_bacterial_intoxication_syndrome_(CBIS)_theory_of_ME/CFS

Dr. Igor Markov hypothesized that chronic low-level kidney infection was leading to the overall entity called ME/CFS and that vaccination made from the patients’ own bacteria could be a cure. Dr. Markov does have a remarkable cure rate…over 90%.

I might dismiss this as just another theory, but then I remembered my grandmother who had been plagued by chronic urinary tract infections until a doctor created a vaccine from her own bacteria and this cured her chronic infections. This was before they threw antibiotics at everything.

Dr. Markov does take remote patients, but the problem is that he is in Kiev Ukraine and I am not sure what the clinic’s status is right now. I am going to look into it. Because of my family history, this might be what I have been looking for.

That is really interesting Betty. I remember when I fell ill in 2017 I felt poisoned and was sure I was somehow. I had a UTI at the time also, incidentally found at the ER, and what I realize now was some kind of ANS malfunction. I could not stand without dizziness or the feeling someone was pushing down on my head. I had my first headache bout, that one lasted 10 weeks. I have been plagued by UTI’s from different bacteria, never understanding why, and test results I have had have led me to wonder about LPS. I even had my PCP test my blood for sepsis as it felt like that to me. I have not had the kind of kidney pain you describe however. Bacteria, viruses, fungi, biotoxins, vector illnesses, trauma, injury, overexertion, intense stress….all physical insults of one kind or the other. Our bodies can’t seem to move through it to the other side. We are stuck with the innate immune system button stuck in the on position.

By any chance were you treated with a Fluroquinolone for your uti ? ie Cipro , Levequin …..?

Carolyn, good question!

I am curious too.

Merci pour le lien Betty.

Voici ce qui est écrit dans l’article “Le Dr Igor Markov déclare qu’il a traité 4288 patients atteints d’EM/SFC (enfants et adultes) avec sa thérapie autovaccinale entre 2009 et 2021, et rapporte que 93 % de ses patients atteints de néphrodysbactériose ont obtenu une guérison complète et permanente de l’EM/SFC ( bien qu’il dise que certains patients peuvent rechuter après 5 à 7 ans, mais cela peut être résolu avec une thérapie autovaccinale supplémentaire)”.

Si cela est vrai, ça vaudrait le coup de faire des analyses de sang et d’urines pour rechercher ce genre de bactéries . A voir si cela est faisable dans nos pays…

Thanks for the link Betty.

Here is what is written in the article ‘Dr. Igor Markov states that he treated 4288 ME/CFS patients (children and adults) with his autoimmune therapy between 2009 and 2021, and reports that 93% of his patients patients with nephrodysbacteriosis have achieved complete and permanent recovery from ME/CFS (although he says some patients may relapse after 5-7 years, but this can be resolved with additional autoimmune therapy)’.

If that’s true, it might be worth doing blood and urine tests to look for such bacteria. To see if this is feasible in our countries…

Thanks for your comments. The key will be to discover whether Dr. Markov’s clinic is still operating in Kiev or whether any clinicians in other places are using the same testing and treatment protocols.

How to improve the microbiome of mice:

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6859693/

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31596658/

https://journals.lww.com/cmj/fulltext/2021/03200/light_therapy__a_new_option_for_neurodegenerative.2.aspx

The gut connection is super interesting. Thanks for writing about it! Relatedly, high-dose thiamine also reduces the pro-inflammatory th-17 process, leading to reductions in IL-17 cytokines. Perhaps this explains why so many people responded to my high-dose thiamine survey by saying it reduced post-exertional malaise and fatigue? Here are some links if people want more info:

(a) evidence for high-dose thiamine reducing IL-17 cytokines: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fphar.2020.598128/full .

(b) My write-up in Health Rising of the initial results of my high-dose thiamine survey, noting reported reductions in PEM and fatigue: https://www.healthrising.org/blog/2021/06/02/fibromyalgia-chronic-fatigue-syndrome-benefit-high-dose-thiamine/

(c) Updated tables from final, long-term results of the high-dose thiamine survey: http://www.high-dose-thiamine.org/results-of-high-dose-thiamine-survey/

(d) My initial article in Health Rising on why high-dose thiamine may reduce fatigue in individuals with ME/CFS, EDS, and Fibromyalgia: https://www.healthrising.org/blog/2021/04/15/thiamine-b-1-chronic-fatigue-syndrome-fibromyalgia/

(e) A Medium post with a longer discussion of the evidence on why high-dose thiamine may reduce fatigue, that I’ll soon be amending to add the exciting findings on th17/IL-17 that Cort discusses above. https://medium.com/eds-perspectives/why-does-high-dose-thiamine-relieve-fatigue-in-individuals-with-diverse-neurological-conditions-40a3502f6439

Interestingly, the most rigorous evidence thus far of the benefits of high-dose thiamine in reducing fatigue has come from an RCT of its use in people with IBD. There’s the gut connection again!

Thank you for such a well constructed and understandable explanation of your study results. I have just started trying thiamine. Right now I am using a liquid benfotiamine 250, 1ml that includes 10mg thiamine to cut down on side effects. Going to get pretty expensive though as the dosage goes up, small tincture bottle. Any thoughts on benfo being the best to use and the end dosage? The middle category range looks reasonable. I fear I will get sick on a lot of tablets.

I don’t have any experience with liquid benfo or other thiamine, but perhaps others do, sorry. Hope you find some benefits! My daughter currently takes 600 mg thiamine hcl in 3 divided doses (Swanson brand) plus the 50 mg in her b complex (Thorne Stress B complex). She also takes 1/8 of a 50 mg allithiamine capsule each morning.

Thank you so much for your easy to read posts.

The link between IBS and mononucleosis is really interesting. I can date the start of my ME symptoms following a virus (a cold-another type of coronavirus perhaps?), but 18 months earlier I had mono… Brought home from day care I suspect.

I remain hopeful with all the research that we will find better treatments… Maybe even prevention or cures for those early in the disease.

Reading the comments, I think thiamine looks promising to help with the crippling fatigue.

From my research it seems like supplementing vitamin A would be very helpful to increase tregs and improve gut function? https://selfhack.com/blog/treg/