It’s very good to see this case report. Chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS) experts are now bringing decades of experience to bear on treating long-COVID patients. Many are using treatments that long-COVID patients may not even know exist. Case reports like the one below give doctors of all stripes access to potential new treatments. Let’s hope that many will read this one.

Throughout his career, Dr. Rowe has uncovered numerous new diagnoses in ME/CFS.

Peter Rowe MD has been researching and treating chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS) and postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS) for decades. He was one of the first to document orthostatic intolerance (problems standing) in ME/CFS, was the first to describe neuromuscular restrictions, and with two Dutch researchers (Visser, Van Campen), has been uncovering the blood flow problems present.

That Visser-Van Campen-Rowe team was responsible for what I believe is one of the most significant findings to come out of the ME/CFS field in the last decade – that blood flows to the brain are reduced upon standing not just in people with documented orthostatic intolerance but in virtually everyone with ME/CFS.

Rowe has also documented the existence of orthostatic intolerance (when being upright causes symptoms)and reduced blood flows to the brain in long COVID. In fact, blood flows to the brain were more severely impaired in the ten long COVID patients in the study than in many people with ME/CFS.

Like other ME/CFS experts, Rowe has his own slant. He’s heavily focused on the autonomic nervous system and orthostasis, the functioning of the spine, restricted ranges of motion, joint hypermobility, and mast cells.

The Case Report

Lindsay Petrachek (first author) and Rowe (senior author) published the case study, “A Case Study of Successful Application of the Principles of ME/CFS Care to an Individual with Long COVID“, of how a 19-year-old returned to near complete health.

The patient was 19 years old with a history of allergic inflammation. His mild coronavirus case was confirmed with PCR. Over the next two months, he noted an increase in heart rate as well as problems exercising that caused him to take to bed for several days. Other than a “mildly reduced peak oxygen uptake” (84%), cardiovascular testing revealed no abnormalities.

His main symptoms were constant fatigue, unrefreshing sleep, lightheadedness, post-exertional malaise after mild increases in activity, bi-frontal and bi-temporal headaches, occasional cough, chest pain, leg pain, and mild anxiety and depression. His overall wellness score (100 before COVID) was 45, indicating a “moderate to severe impairment in function”.

Rowe has found an increased risk of joint hypermobility in his adolescent patients.

Restricted Range of Motion

Rowe brought the issue of a restricted range of motion (ROM) or “neuromuscular strain” to the fore in ME/CFS, and uses various assessments (seated slump testing, ankle dorsiflexion, passive straight leg raise, brachial plexus strain testing, prone knee bend, prone press up).

Rowe has also pioneered the use of structural spinal assessments for spinal stenosis, Chiari malformation, and craniocervical instability in ME/CFS/FM, and has produced case reports of ME/CFS patients who’ve recovered after spinal work. Rowe uses the presence of “brisk reflexes” and the presence of the “Hoffman sign” to initially assess if these problems might be present.

Hoffman Sign

The Hoffman sign is a quick and easy test to determine if spinal cord compression is present. Note that anxiety, hyperthyroidism, and the use of nervous system stimulants can produce positive results. If someone has a positive Hoffman’s sign on only one side, though, that is apparently more likely to indicate a nervous system injury.

To perform the Hoffman test:

- Hold out your hand and relax it so that the fingers are loose.

- Have someone hold your middle finger straight by the top joint with one hand.

- Have them place one of their fingers on top of the nail on your middle finger.

- Then have them flick your middle fingernail with their fingernail.

If the index finger and thumb of that hand move, the test is positive. If the index finger or thumb of that hand doesn’t move, the test is negative.

NASA Lean Test

Noting that “over 95% of adolescent and young adult ME/CFS patients” show evidence of orthostatic intolerance, Rowe does an “inexpensive, ten-minute passive standing test” in everyone with ME/CFS. First, the patients lie down for five minutes, then stand quietly with their shoulders against a wall for ten minutes while their heart rate and blood pressure are taken. Also called the NASA lean test, this is a test that can easily be done at home.

Blood Tests

Rowe also does the following tests:

- complete blood count (CBC) with differential white blood cell count (WBC),

- erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) or C-reactive protein (CRP),

- serum chemistry panel,

- free T4 and thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH),

- urinalysis,

- iron studies (ferritin or iron/total iron binding capacity),

- vitamin B12,

- celiac screening.

He may also assess histamine, chromogranin A [in those not on proton pump inhibitors], tryptase, and other mast cell mediators if allergic and mast cell symptoms are present, and in this patient’s case, he also did a Lyme screen.

The authors validated their mast cell testing regimen based on the known mast cell connections with POTS, the patient’s long history of allergic inflammation, his symptoms after exposure to cherries, cashews, and carrots, and his parents’ similar history.

They also make a case for suspecting mast cell activation syndrome (MCAS) in long COVID. One study found MCAS inhibitors were helpful, while other studies suggest that H1 antagonists may have antiviral properties, and may inhibit ACE2 activity, while H2 blockers such as Famotidine may inhibit G protein-coupled receptors. Cromolyn, ketotifen, ebastine, and loratadine were also found to reduce mast cell degranulation after a SARS-CoV-2 challenge.

Results

This young man’s Beighton score did not quite meet the criteria for hypermobility. His ROM (range of motion) tests revealed several limitations and his Hoffman sign was positive on both sides. A cervical spine MRI, however, showed no cervical stenosis (a narrowed spinal cord canal that is pressing on the spinal cord or “cerebellar tonsillar descent below the foramen magnum”; i.e. no evidence of Chiari malformation.

The NASA Lean Test, or passive standing test, showed that his heart rate increased 70 beats per minute (bpm) upon standing – well above the cutoff range for postural tachycardia syndrome (>40 bpm) (POTS). His headache also increased.

His blood results were normal except for high total bilirubin, plasma histamine and chromogranin A – resulting in him meeting the criteria for a “consensus-2 definition” of mast cell activation syndrome (MCAS).

Diagnosis

The testing results suggested that this patient’s primary problems appeared to be:

- profound postural tachycardia syndrome

- allergic inflammation, the elevated histamine and chromogranin A that were suggestive of mast cell activation syndrome (MCAS)

- an increase in sensory sensitivity

- reduced range of motion on physical therapy screening tests.

Rowe has taken his own slice at ME/CFS. While his list of possible other comorbidities contains some that any ME/CFS expert will probably look for (migraine, gut motility, Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome), others demonstrate how aware he is of structural abnormalities that can cause or contribute to these diseases. They include:

- neurogenic thoracic outlet syndrome

- venous insufficiency (pelvic congestion syndrome with ovarian and internal iliac vein varices, May Thurner syndrome with compression of the left common iliac vein)

- neuroanatomic abnormalities (Chiari malformation], cervical spinal stenosis, atlantoaxial instability, or craniocervical instability).

Treatment

The authors began with non-pharmacologic therapies but moved “relatively rapidly to pharmacologic therapy as indicated”.

POTS Treatment

They started off with simple things to do for orthostatic intolerance:

- increasing fluid intake, aiming for at least 2 L of oral fluids per day

- increasing the intake of high-sodium foods, liberal use of the salt shaker, and, if needed, using salt tablets and electrolyte packets

- compression garments (stockings, abdominal compression, and body shaper garments), usually at 20–30 mm Hg for stocking compression but up to 40 mm Hg for those who could tolerate them

- standing with the legs crossed, shifting weight when standing, sitting with the knees elevated above the hips (for example, resting the feet on a knapsack or camping stool), or leaning forward when sitting.

In moderately impaired patients, they move to drugs within a couple of weeks. Three classes of drugs are used – often eventually together – as they go through them, one by one, in an attempt to find the best solution.

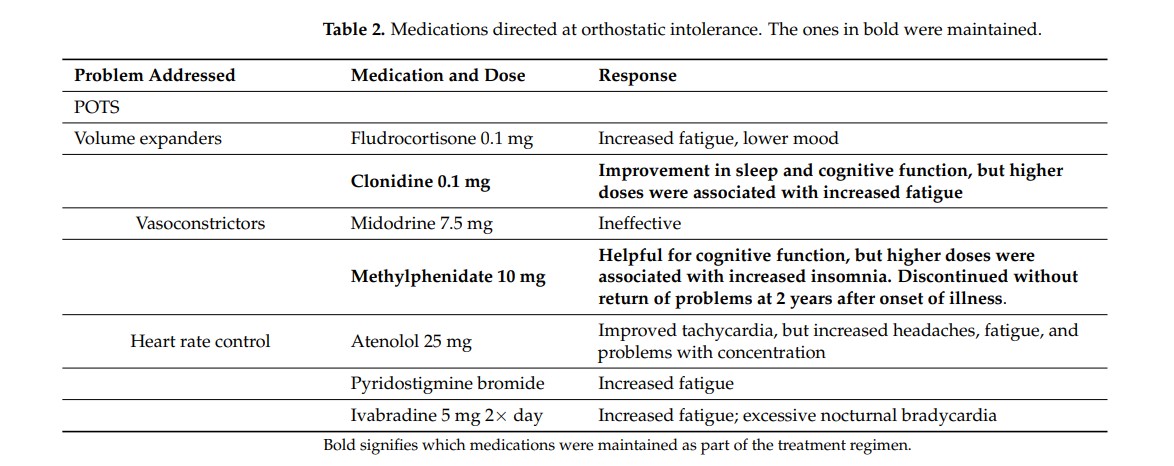

The three main drug categories are drugs to: (1) improve vasoconstriction, (2) improve blood volume, and (3) control heart rate and catecholamine release or effect. As the charts show, the Rowe team tried 15 different drugs. Interestingly, of the 7 drugs known to be helpful in POTS, 4 actually ended up increasing the patients’ fatigue, while two (methylphenidate/clonidine) were effective and retained.

Orthostatic intolerance drugs: the ones retained are in bold.

- Dig Deeper – Drugs for Orthostatic Intolerance

- Dig Deeper – Treating Orthostatic Intolerance

The high failure demonstrates how heterogeneous a condition POTS is – some drugs designed to help can make things worse. The POTS saga also demonstrates how patient both the doctor and patient have to be. It took time to hit on the right drugs at the right dosages.

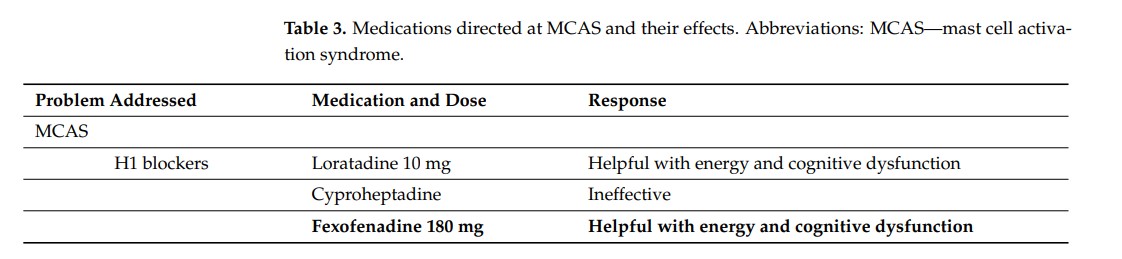

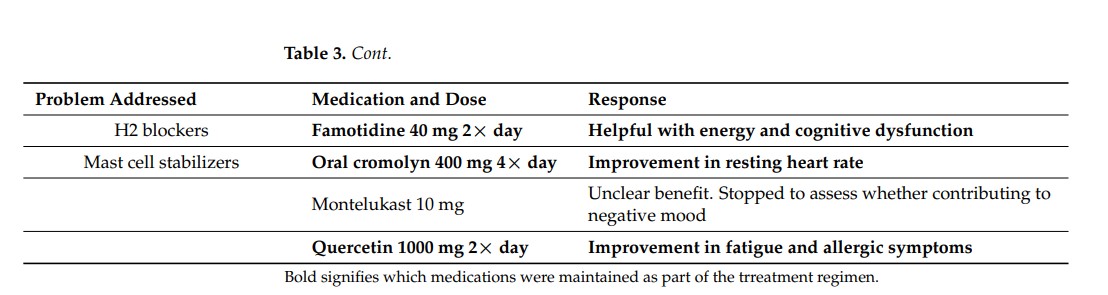

Mast Cell Activation Treatment

The mast cell drugs and supplements, on the other hand, were much better tolerated and had a higher success rate. Of the seven drugs/supplements, only 2 were ineffective, none produced side effects, and four (Fexofenadine, famotidine, oral cromolyn, quercetin) were eventually retained. That’s quite an outcome for a field that gets almost no research and is almost totally neglected by general practitioners.

Note that fexofenadine (Allegra) and quercetin are over-the-counter drugs or supplements that are readily available and famotidine (Pepsid) is a generic drug that doctors are familiar with. Loratidine (Claritin) was effective but didn’t end up being used. It, too, is over the counter. The upshot is that mast cell activation syndrome – which apparently played a big role in this person’s illness – can, in some cases ,be treated quite easily and cheaply.

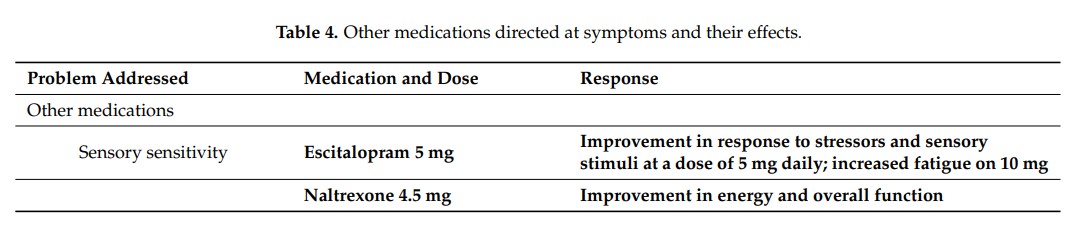

Sensitivity Treatment

Low-dose naltrexone (LDN ) is commonly used by ME/CFS experts. It requires a prescription and a trip to a compounding pharmacy but is very affordable. It improved this patient’s energy and overall function. Low doses of an antidepressant, escitalopram (Lexapro), helped to calm his nervous system down and help with sensory issues and stress.

Treatment Response

For the first year of his illness, the patient was able to take online college courses. A year after his initial infection, his remaining symptoms included daily fatigue, unrefreshing sleep, and post-exertional malaise. Lightheadedness and headaches were infrequent. He was able to handle a virtual 40-hour-a-week internship.

By fall, 15 months after his infection, he had the stamina to attend in-person courses and to walk around his university campus.

At this point, he began physical therapy to address his movement restrictions. After these had been treated, he began a graduated stationary biking regimen. Note that Rowe did not start him on an exercise regimen for almost a year and a half, or after his condition had improved and until his orthostatic intolerance and his movement restrictions had been addressed with physical therapy. The authors stated that:

“Our experience has been that it is critical to treat orthostatic intolerance before advancing aerobic activity and that such advances need to be flexible and conducted in a manner designed to avoid the provocation of PEM.”

David Systrom has a similar approach; he does not recommend exercise therapy until Mestinon or other treatments have resulted in improvement.

With the movement restrictions removed and his health improved, this patient was able to increase his exercise levels fairly quickly without provoking post-exertional malaise. By September 2021, he was biking 15 min twice a week; by October, 20 min three times a week, by November, 25 min four times a week, and by January of last year, he was biking 30 min four times a week without any symptom exacerbation. It took him just four months to be able to bike 120 minutes a week.

In March 2022, he began to slowly resume a more challenging upright exercise – running. Again, he started slowly – 10 min four times a week. Charting his heart rate levels and watching for symptoms of post-exertional malaise, he slowly increased his running time by two minutes each week. Seven months later, in October 2022, he was able to compete in an 8K cross-country event. The only disappointment was that his race time was considerably slower than before he was ill; i.e. he’s not completely back.

Orthostatic Intolerance – A Common Missed Diagnosis?

The passive standing test indicated that this young man did have POTS, but what about people who don’t test positive for POTS? Does that mean they don’t have orthostatic intolerance? In light of the Visser-Van Campen-Rowe team’s results – which were obtained using specialized equipment – I asked Rowe how he dealt with ME/CFS and long-COVID patients who don’t meet the criteria for POTS or other types of orthostatic intolerance. He noted that most people with ME/CFS actually don’t meet the criteria for POTS!

“van Campen and Visser show that although 58% of adults with ME/CFS have no evidence of POTS or delayed orthostatic hypotension during a 30-minute head-up tilt test, and might have been at risk of being dismissed as “normal” if we used only the HR and BP numbers.”

Therefore, in their clinic:

“we look carefully at the history of how people do when in quiet upright postures, asking specifically how they feel when standing in line, shopping, showering, going to a museum, or at receptions. Keep in mind that not everyone with OI reports lightheadedness, but they will report feeling unwell in those positions, especially when upright posture is combined with a warm environment.”

and that,

“we do not require that people have an abnormal HR or BP response in order to offer empiric trials of therapy. If one were to insist on demonstrating HR and BP abnormalities during tilt or standing, then this would withhold therapy from the majority of adults who have objective cerebral blood flow evidence of treatable orthostatic intolerance.”

Conclusions

Interestingly, Rowe was apparently able to help return this long-COVID patient to approximate health without using any of the kind of hot-button treatments being tried in long COVID such as anticoagulants or antivirals. Nor (except for quercetin) were supplements, dietary changes (except for increased intake of salty foods), or heavy-duty immunomodulators part of his treatment package.

Note that many people with ME/CFS or long COVID do not meet the criteria for POT but still have orthostatic intolerance. Rowe uses the passive standing test and careful questioning to determine if symptoms of orthostatic intolerance are present and then treats accordingly.

The study is free to download and print out and take to your doctor, if you wish. (Rowe, it should be noted, is a pediatric specialist and typically has a long wait list.) Except for the MRI, the testing regimen appears to be relatively inexpensive and certainly within any doctor’s or RN’s capabilities. You might also want to print out Rowe’s earlier paper “Orthostatic Symptoms and Reductions in Cerebral Blood Flow in Long-Haul COVID-19 Patients: Similarities with Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome” which documented the existence of orthostatic intolerance and reduced blood flows to the brain in long COVID.

For more on how ME/CFS experts treat their patients, check out the U.S. ME/CFS Clinical Coalition, which provides diagnostic, testing, and treatment recommendations.

Found This Blog Helpful?

Please Support Health Rising

Why is my initial reaction anger? Because NO ONE, EVER, paid this much attention to me. I don’t know what evaluation and treatment cost, but getting back to running AT ALL is impressive.

I was a research physicist at the US prime lab for fusion – PPPL – when I got ME/CFS in 1989 (ironically, at a physics conference) – and then was abandoned by the medical profession forever.

And STILL don’t have access to the kind of attention this young man got. Or the capacity to take advantage of it. My ‘medical professionals’ have never made any effort to treat any of my symptoms but pain.

I never asked ‘Why me?’ when I got sick; everyone is subject to fate, and things happen.

But I AM asking myself ‘Why him?’ for getting better. I am happy for the young man, glad he found something and someone that worked, and wondering when, for the rest of us.

Same here. In 1986 I was young and very successful. I have run down at my own expense so many rabbit holes with no answers since then. So much money spent just to get someone that would at least acknowledge I was ill. Now at this age and without those credentials and money I know I mean less than nothing to the medical world. I am jealous too.

We can be jealous together. Except I didn’t have the energy – or the money to spend; disability income, eventually, doesn’t stretch that far.

A friend in my support group DID spend the money on seeing Natelson – until she ran out of money. No results I would pay for – just lots of money gone.

The amount of energy it would have taken, for example, to go see Levine in NYC was out of my ability range.

Thousands of ME/CFS patients have been abandoned over the politics of the Big Pharma/US Government vaccination lobby.

In addition, a leading research scientist was even excommunicated from government-grant research because she attributed ME/CFS to vaccinations, of which, the first major cases were medical professionals employed at Los Angeles General Hospital in 1938.

The scientist is Judy Mikovitz, PhD. Her intriguing book is:

“Plague: One Scientist’s Intrepid Search For the Truth About Human Retroviruses and Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS), Autism, and Other Diseases”. She now owns an independent lab in Ventura, California. She has a LinkedIn.com presence.

Her book (Amazon.com) reveals the repugnant and ugly politics of the National Institute of Health, the CDC and the FDA. and corrupt relationship with corporate oligarch entities known as Big Pharma and Big Medicine.

You might want to check out some alternative viewpoints. You probably weren’t there during the XMRV saga when she told the media it was in breast milk, that XMRV was going to make HIV-AIDS look like a cakewalk etc. based basically on nothing. (It turned out to be a lab contaminant.

Things only got worse after that. She’s about as discredited a scientist as you can get.

https://www.science.org/content/article/fact-checking-judy-mikovits-controversial-virologist-attacking-anthony-fauci-viral

https://qz.com/595909/why-bad-science-wont-ever-die

Mikovitz, darling of conspiracy theorists and Queen of misinformation.

Many of us long term ME patients lived through the XMRV debarkle. Best not to insult our intelligence holding her up as some kind of hero.

Unless you are a product of the USA virology academic PhD educational system, of which, Judy Mikovits is a product of, I would not be so judgemental unless, of course, you wish to also judge said educational system.

The reason there is no remedy for ME/CFS and autism is because of the politicized and corrupt nature of the NIH and/or government research grant system that favors those who wish to contribute to the corruption, of which, is not taught in the medical/virological PhD educational system.

Unfortunately with you being a ME/CFS victim, you and your fellows victims are subject to the corruption of the latter entities. Also, unfortunately, there is no solution since the corruption is systemic since the USA became an oligarch many decades ago. In this case, its all members of Big Pharma and Big Medicine who all naturally must contribute to the corruption to be financially successful. In this case, Dr. Judy Mikovitz became a victim of the corruption because she became critical of the the über-profitable sanctity of the USA/European “vaccination/immuno-modulation” system.

President Ronald Reagan said it best, “government is not the solution; it is the problem”. Dittos for Big Pharma, Big Medicine and the alphabet government entities known as NIH, NAIAD, CDC, FDA and Fauci et al.

I had the same feeling. I love the patience the Rowe team took with this patient – trying drug after drug until they found ones that helped. I’ve seen several ME/CFS experts and their slants are all a bit different – Rowe really focuses on orthostatic intolerance and in this case, it worked.

Same here.

I fell ill in 1986 at age 15. No test whatsoever at that time except, two month later the standard blood test that revealed EBV, toxoplasmosis and low lymphocytes (20% below lower limit). Except an exclamation mark on the lab sheet, no investigation was made. The doctor smirked when he said, “kissing disease”.

I had my first cardiac echography at age 29 (by then I was a severe ME/CFS case). I also had a neurological assessment that showed a series of problems but nothing was suggested other than CBT.

It took 10 years of negotiation to get a scan to check the severity of pectus excavatum (Haller index of 12). Surgery followed at age 45 and fixed 85% of my orthostatic intolerance and arrhythmia. It put an end to 17 years of being totally bedbound. Since then, I had a diagnosis of EDS, again after 5 years of asking around for a proper test to be performed.

I’m now trying to see whether or not I have cranial instability. A MRI showed moderate cervical stenosis in several places according to the radiologist. A rheumatologist said I have nothing (he also said rheumatoid arthritis was a male disease :/ ).

The very few progresses that were made was because *I* insisted for years to get the test. I never had a POTS test, never had a sleep test, my pain was never treated. I remember once I lost consciousness in the metro because of pain. I was told “it is normal to feel a bit sore sometimes”. Any meaningful test happened because I initiated the move.

The reason why nobody has cared the slightest is because I was a young girl/female, and was consulting doctors on my own. I was offered breast implants for pectus, yoga for EDS and “to forget about diplopia”. I was told my symptoms were caused by lack of self-confidence and the fact I was not married. Nobody ever cared about my quality of life or wellbeing. I am now 52, and I hope I have very few years left.

I am glad for this young man. I hope he knows he’s had this preferential treatment because of his gender.

It is a case study. Doesn’t say anything to me. But i am happy for the young men.

They don’t even know what long covid is. How long was this young men sick?

Many people are getting better after covid. It can take a long time but it is just the same with many virus infections. It is nothing special with corona. Many feel better after omega3 or vitD also. We need RCT.

was the MRI for neck, etc an upright fmri Cort?

yes, i feel “a bit” the same as Alicia. Long covid research not only gets the ideas/clues from ME/cfs, ME research (where are the centers of excellence gone?) gets still no funding, long covid gets so much funding and research and now even our specialist(s)! crazy!!!

It’s crazifying – to make up a new word – that’s for sure! I think in the long run it will all work out but its a weird time.

The paper said this with regard to the MRI – “A cervical spine MRI showed no cervical stenosis or cerebellar tonsillar descent below the foramen magnum.”

I have significant spinal stenosis – can’t walk or stand – but it is POST ME/CFS (which started in 1989), and was caused by the spinal surgeon who messed up in 2007.

I don’t have the ability or the energy to find someone who might fix it (didn’t trust the surgeons I have seen since then) – but I’d have to be in a lot better shape to withstand surgery and PT after, so I’m waiting until someone (?) fixes the ME/CFS for me FIRST. Once that happens, maybe I can walk again.

Very important article! Thanks, Cort. Peter Rowe has run an me/cfs clinic at Johns Hopkins for many years, and for many years, has been a hero of mine, for his practical and sensible approach.

Both the head of the big NIH research program and that program’s head of immunology, have said that they now believe that once they’ve figured out the immune-system dysfunction in long covid, they’ll have also figured out me/cfs, long Lyme, and other post-infectious syndromes. They say that it doesn’t matter what infection triggered the initial immune dysfunction; what’s important is identifying that initial immune dysfunction and the dysfunction that follows. (As you’ve reported before, thanks.)

My local PCP has expressed frustration with seeing so many clients that she can’t help. Specialists are also overrun, and have little treatment to offer. This outline of testing and treatment is exactly what docs and patients need, to address their issues.

Thanks also for the link to the US Clinical Coalition.

It’s very encouraging to see these links being confirmed; and information made easily available to doctors and patients. The doctors may be slow to get on board, as in the past. But patients can help themselves, and tactfully help inform their doctors too.

Great job, Cort, on keeping us posted. Kudos to you!

Glad to hear that she’s frustrated..the more frustration the more pressure to find out what’s going on and develop good treatments.

“My local PCP has expressed frustration with seeing so many clients that she can’t help. Specialists are also overrun, and have little treatment to offer.”

Great article! Thank you Cort. However, I do wonder if there’s a typo. It was stated that low-dose naltrexone is “very affordable”. I suppose it’s all relative but I find it to be expensive and insurance doesn’t cover it.

Good point about LDN, as it is expensive if your insurance won’t cover it and you need to have it compounded. That said, the 50mg tablets are cheap. Has anyone else been “self-compounding” by dissolving the 50mg tablet in distilled water? Is there a DEFINITIVE answer on whether this is effective or not? My GP gave me the green light, though I am not sure if he had evidence to support this form of administration.

Brian, I have been doing this for two years now. I can’t take the capsules that are compounded because they have too much other crap in them and cause much pain in my stomach. I get the 50mg tablets (but you could use the 100mg tablets instead) both of which are cheap. I grind up one 50mg tablet with a small mortar and pestle. Then I dilute the resulting powder with 16cc of distilled water. Then I put it into a dropper bottle and let it sit for 24 hours to let the excipients settle out. I draw up 1cc of the clear liquid on top to equal 6mg LDN. I put this 1cc into water or tea at bedtime and drink it. There are approximately 15 nighttime doses in each 50mg tablet.

This helps me a lot, but I must caution anyone trying it to begin extremely slowly. I am using 6mg, but the most common dose is 4.5mg. You would need to do a bit of arithmetic to figure out how to dilute the powder to make 4.5mg in one cc. If you dilute the powder, then begin with ONE DROP at bedtime and increase by one drop every week. You will have vivid dreams, but I’ve come to enjoy these. It took me several starts and stops before trying the slow start up method to hit on the right dose for me. After 8 months I was up to 6mg.

You can also have a compounding pharmacy make a topical for your dose in a metered squeeze bottle, but that is expensive.

Information about LDN can be found here:

https://ldnresearchtrust.org/

The LDN Research Trust

I highly recommend ldn.

Years ago Dr Irma Rey at NOVA (Florida) gave me a prescription for the 50 mg tablets so I could experiment with LDN. I couldn’t get beyond a minuscule dose without side effects, but I spent almost nothing for one tablet and some spring water.

Great article for many “newbies”. Thank you!

I believe these treatment strategies do prove therapeutically beneficial and can attest to this personally. Not a cure, nor a recovery, but definitely supportive.

Not to be pessimistic but I do read with caution anytime these recovery blogs are posted about men, especially 19 years young. Comparatively speaking, women seem to bear the brunt of this illness with far greater numbers and far lesser recoveries. Nonetheless, I’m grateful for anyone’s recovery, male or female, young or old. Knowing some of the men featured in the “cured” stories posted here are not in fact cured, it’s important to remember to take helpful information and stories with a grain of salt.

Thankfully most of the doctors who initially tested and treated me 7 years ago were already practicing these tests and models of care. While they didn’t produce a recovery in me, they do help!

I wonder why they didn’t trial Zyrtec in the H1 blocker category? I thought that was pretty much the most commonly used drug in that class for MCAS.

Thank you for reporting on this case study – and for setting out the testing & treatment protocol in an easy-to-follow format (as always).

Any paper by Dr Peter Rowe is worth its weight in gold for ME/POTS patients, most of whom have no access to a specialist clinician like him.

It’s also interesting – and not at all surprising to anyone in the ME field – that his ME/POTS testing & treatment applies equally to long-COVID patients (chronic illness post-acute infectious disease).

“Any paper by Dr Peter Rowe is worth its weight in gold for ME/POTS patients” – agreed 🙂

Hmmmm!… I have ME/CFS (40+ years) and I have never been diagnosed with/ tested for POTS.

I feel unwell while standing in line or standing still in just about any situation. But I notice that if I start walking I will tend to feel better…. Even though walking technically uses more energy. So this is common with ME then?

This is actually, I think, quite common. It’s why people with OI tend to fidget and move around when they’re standing – they’re tensing the muscles in the lower body in order to push blood back up. The worst thing is standing still. That’s my understanding.

You can probably test POTS on your own.

If your heartbeat jumps up 30 beats or more after getting upright: it’s POTS.

If you heartbeat goes up less, a (temporary) lower blood pressure also helps to adjust to an upright position.

Walking or fidgeting takes more energy but also pumps more blood to your head and diminishes OI problems.

Try the NASA lean test linked in the article if you can. Be careful of fainting and have a chair or something soft to collapse nearby.

It’s handy to have someone with you to write down the readings, but it can be done alone.

You can also ask your doctor to do the test. Referring to “orthostatic vitals” may help to introduce the topic.

Very happy for this young man!! I’ve always been impressed with the approach of Dr. Rowe.

Thanks for the article and for details of the Hoffman test too.

Cort, I heard that dr.Prusty have found something that can lead to a breakthrough(?). If i am correct. I hope that we will not be disappointed again.

https://www.tlcsessions.net/episodes/episode-54-dr-bhupesh-prusty-molecular-virologist

Dr Prusty hopes to publish his findings on this in the next month, and will present his model at the 12th Invest in ME Research Biomedical Research for ME Colloquium #BRMEC12 and 15th International ME Conference #IIMEC15 2nd June. Patients are welcome to attend.

The one tiny bit about Quercetin is very useful! It’s the only antihistamine I tolerate, but I take one x 800mg as needed. I’m now trying 2 2x a day to see what happens to my overall heightened reactivity.

Case reports can give people the illusion that the best method is unbiased randomized controlled trials rather than case reports.

Dr Rowe seems like a lovely man as well as being an excellent doctor and researcher.